In spite of their 15–0 season and AAFC championship, the Browns had to share the sports headlines on December 20 with an unexpected development.

Hours after his team’s resounding victory over Buffalo, Browns majority owner Mickey McBride found himself huddled with Bills owner Jim Breuil, 49ers owner Tony Morabito, Yankees owner Dan Topping and Dons owner Ben Lindheimer in a suite at the Hotel Cleveland. They weren’t popping champagne corks (especially not Breuil) and toasting McBride’s team and its continued success. They were plotting strategy for a hastily arranged meeting with the owners of the 10 NFL teams the following morning in Philadelphia. The five men who’d represent the AAFC departed from Cleveland’s Terminal Tower train station at 8:05 that evening. Their meeting with their NFL counterparts would begin the next morning at 10:30. Hopes for the oft-mentioned sensible solution to professional football’s problem soared.

“Since they’re coming here, I assume they have something to offer,” said Giants owner Tim Mara, one of the older league’s staunchest hawks in the war with the AAFC. Mara then injected a note of humor, or perhaps derision. Referring to AAFC commissioner Jonas Ingram, he added, “This is the first time I ever heard of an admiral looking for peace.”1

Rumor had it that the owners would discuss mergers between some of the weaker franchises in both leagues. One rumor claimed Ted Collins’ Boston Yanks would merge with Topping’s Yankees and the combined team would play in Yankee Stadium under the AAFC banner. That would have satisfied Collins’ desire to move his team to New York. Another rumor suggested the Cardinals and Rockets would merge.

The confab in Philadelphia was a flop. After a long day of meetings, it was announced on the evening of December 20 that “representatives of the National Football League and the All-America Conference concluded a meeting tonight in Philadelphia. Efforts by both sides to formulate a mutually satisfactory agreement were not consummated. The committees terminated the meeting with the expectation that future meetings might provide some formula for a common understanding between the leagues.”2 The gulf separating the AAFC and the NFL was too wide to be bridged with one day of discussions. It was believed the major stumbling block was the insistence by the owners of the Colts that they be included among the teams absorbed by the NFL. The older league was prepared to welcome the Browns and 49ers, but not the Colts. Redskins owner George Preston Marshall was understandably unwilling to accept a team some 25 miles to the north of his, and that killed the deal. Or at least helped to.

“The trip to Philadelphia was useless,” snorted McBride upon his return to Cleveland. “We became involved in a subject we refused to discuss before. We wanted to talk leagues, and the NFL wanted to discuss two teams. We had turned them down on that proposition many times, and if we knew that was the way the meeting would go, we wouldn’t have bothered to make the trip.”3

As NFL commissioner Bert Bell had said, peace would be achieved only on his league’s terms. And, in the opinion of Whitey Lewis of the Press, Bell’s terms were the same terms that General Douglas MacArthur had presented to the Japanese in August of 1945: unconditional surrender.

McBride laid the failure of the talks on Marshall’s doorstep. “He was the fly in the ointment,” said the Browns’ owner. “He absolutely refused to recognize a league which contained the Baltimore Colts. He insisted on his territorial rights, which prohibit a rival pro club from operating within 100 miles of Washington. I think that if we had agreed to disband the Baltimore franchise, Marshall would have gone along with us.” McBride then conceded that he and his fellow AAFC owners had to shoulder some of the blame for the collapse of the talks. “We were as stubborn as he was on that score. The rest of the NFL people were very decent.”4 Marshall was, and would continue to be, the NFL’s most intransigent owner. He steadfastly, and at the expense of his team’s success on the field, refused to integrate the Redskins through the 1950s. Marshall wouldn’t allow African-Americans on his team until he was pressured to do so by the federal government in 1962. Marshall was used to getting his way, all the time.

“It was just a lot of double-talk,” snorted Marshall. “If the All-America Conference wants to continue for another year, let it do it. That will get them tireder.”5

Tired or not, McBride, whose Browns were coveted by the NFL, reiterated that he wouldn’t abandon the AAFC. “We’ll carry on as a separate league if we have to do it with only four or five clubs. I am going to sink or swim with the fellows who have invested so much money in the conference franchises over the past three years.”6

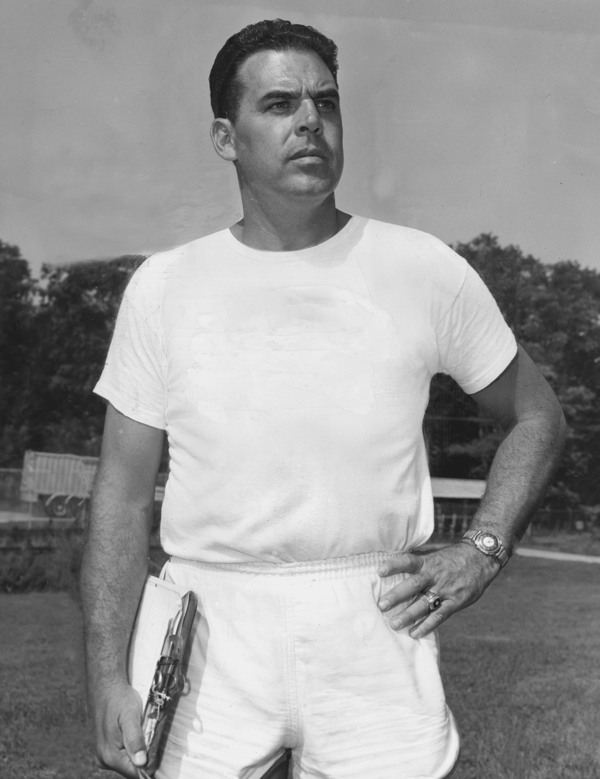

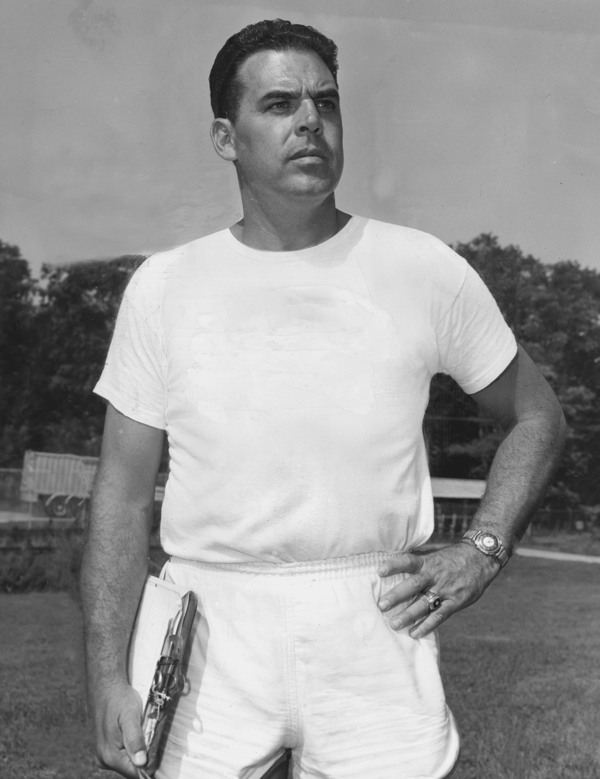

The failure of the peace talks didn’t put a damper on the Cleveland Touchdown Club’s luncheon honoring Paul Brown on December 21. Neither did the absence of Branch Rickey, who pulled out of his speaking engagement. All of the AAFC’s coaches except Baltimore’s Cecil Isbell were in attendance, and two of them were selected to replace Rickey at the podium.

“I’m getting a little tired of congratulating this fellow, because I do it twice every football season,” said San Francisco coach Buck Shaw. “But I’d like to say you won’t find a higher degree of sportsmanship in a coach or a team in any university in the country. You have the best in America right here in Cleveland.”7

Shaw reiterated of the Browns, “It is the best football team in America. But I do get a little tired of losing to Cleveland … five times in six starts.”8

“He’s the best,” said soon-to-be former Rockets coach Ed McKeever. Winning just one game in a season isn’t conducive to job security, and McKeever would soon lose his. “He conducts himself in a way that makes him very popular with the opposing coaches. I think he is more popular with the opposition than any coach I know.” McKeever joked that he wasn’t pleased with having to sit at the dais with the other speakers when his fellow coaches were placed at a table with Otto Graham, Lou Groza, Lou Rymkus and Lou Saban.

“I’m a little unhappy sitting here at the speakers’ table when the other coaches are down on the floor,” he cracked. “It deprives me of the opportunity to be with some football players for a change.”9 He was clearly referring to the lack of talent he’d coached in Chicago in 1948. It was a burden he wouldn’t have in 1949.

McKeever offered another tongue-in-cheek observation about the banquet. “They always have banquets for winning coaches. Why not a banquet for losing coaches? We need the lift. Winners are always rewarded.”10

Saban was the only player to be called to the microphone. He saluted Brown by saying, “He’s the best known synonym for the word ‘win’ that I know of.”11

Christmas came a few days early for Brown. On top of the achievement of coaching the only professional team in football’s modern era to win all of its games, including the championship game, plus the verbal plaudits from friend and foe alike, Brown was given a food freezer by the Touchdown Club and a golf bag by his assistant coaches. There was no mention of a gift from his players, who may have believed, and rightfully so, that their toil and sweat for the past five months that resulted in an undefeated season and a league championship was enough of a present.

With the failure the Philadelphia peace talks the hot topic of the day, Brown spoke of his frustration with the on-going battle between the AAFC and NFL. “This war just isn’t good for professional football. We want to do what is best for the professional game and not just accept any proposal for peace between the two leagues. I’d like to see professional football built into something as fine as major league baseball, which conducts its business on such a high plane. The big leagues of baseball have their commissioner, and whenever anyone gets out of line, he summons them to his office and gets things straightened out. There shouldn’t be any place for some of these remarks these rival leagues make in football, either. I believe we eventually will get together with the National League because it is the only right way. When a thing is right, something will develop.”

Brown admitted that, during a season filled with rumors about him considering any number of college head coaching positions, he had been tempted. “I have been discouraged at times, and became tired of all this talk about our league folding up, and of the war in general. I got to the point where I thought a nice job on a university campus was the place for me. But I am enjoying coaching a professional team. It is a lot easier than a college job.”12

After the players, with all hope of an AAFC-NFL championship game dashed by the collapse of the peace talks, cleared out their lockers and headed for their off-season residences, the accountants went to work. The total gross receipts from the AAFC title game were a disappointing $112,269.38, compared to the $170,000 the Browns–49ers game generated in November. The Browns share of the pie came to $23,173.02, which the players divided by 40. Each Cleveland player earned $594.18 for winning the league championship. The Bills divided their loser’s share of $15,448.28 by 39. Each Buffalo player got $386.22 for enduring a butt-kicking by the Browns on a cold, snowy Sunday afternoon in Cleveland. The pool to be divided by the two second-place clubs, Baltimore and San Francisco, amounted to a paltry $4,827.41. The Browns’ and the Bills’ team shares were $8,602.92. The weather had something to do with the poor crowd, but most Cleveland sports columnists agreed the fans were certain the Browns would win, and win easily, and they decided they had better things to do with their money (especially less than a week before Christmas) and time than to spend them watching the beating.

There was no time for Brown to bask in the glow of his team’s accomplishment. The job of building the 1949 Browns had already begun. Undefeated AAFC champions or not, Brown wouldn’t stand pat. The AAFC conducted its public player draft on December 21. The secret draft had been held way back in July. The Browns announced only two of the selections they made that day: Doak Walker, the Heisman Trophy winning halfback from Southern Methodist University, and halfback Bobby Stuart of Army. Walker was eligible for the draft even though he had one more year of college eligibility remaining, and he planned to return to SMU in the fall of 1949. When he did turn professional, the Browns would have to compete with the Detroit Lions to get his signature on a contract, assuming the AAFC and NFL were still separate entities, as the Lions had made Walker their top draft pick in 1948. By the time Walker completed his college career, the AAFC and NFL had merged. As part of the merger agreement, the Lions were awarded the draft rights to Walker. The competition for Walker was one of several battles the Browns would lose to the Lions in the 1950s.

Brown explained how his team, with its low draft pick due to its status as the league’s champion, was able to select the reigning Heisman Trophy winner. “We were able to select him ahead of the other teams because most of them were concentrating on boys they were sure would play next year.”13 The Browns, being loaded with talent, could afford to wait for Walker to play his senior season at SMU. The other teams needed immediate help.

For his part, Walker stated the obvious. “I probably would sign with the club making me the best offer—if I signed at all.”14 Walker hinted that he might forego a professional career and move directly into coaching. He may have been coyly trying to improve an already solid bargaining position. That position would evaporate after the AAFC and NFL merged.

Stuart was drafted on the recommendation of Sid Gillman, who’d been Army’s line coach in 1948. Gillman was an Ohio State graduate who’d played for the Cleveland Rams of the second American Football League in 1936 before turning to coaching. He was on the staff at Ohio State before Brown arrived, and signed an eight-year contract to coach the University of Cincinnati the day the Browns drafted his protégé. Brown had no idea if Stuart was interested in playing professional football, or if he’d try to break his military commitment to do so. “We don’t know that he will do this, or whether he can. We’re just taking a chance on him. If he’s available, we want him. Sid was of the opinion that Stuart was responsible for making Army the great team it was this year. He’s supposed to be a great runner.”15 Stuart never played for the Browns, or any other team. Cleveland’s top two draft picks in 1948 never contributed to the team. The dynasty rolled along without Walker and Stuart, although Brown mused in his autobiography about how great the Cleveland offense of the early and mid–1950s would have been with Walker in its backfield. The Browns might not have lost the 1952 and 1953 championship games had Walker been playing for them rather than for Detroit. With Walker playing for the Browns, the Lions may not have won the NFL’s western division titles and faced the Browns in the championship game.

Cleveland also selected pair of Michigan Wolverines in the draft. Like Walker, fullback/linebacker Dick Kempthorn had announced he would return to college to fulfill his final season of eligibility in 1949. Defensive left halfback Gene Derricotte had used up his eligibility and was ready to take bids for his services from both leagues. Neither Kempthorn nor Derricotte would play professional football. The Browns would reach seven more consecutive championship games without them, and without Walker.

Brown estimated that the lack of a common draft would cost each professional football team an additional $3,000 to sign each player. “That’s almost $600,000 more than we need to spend,” he lamented. “Had peace been reached at Philadelphia, a common draft might have been the result. Under it, only one club from the two leagues would have been permitted to draft a player.”

Ingram announced that the AAFC had chosen 192 collegians during its draft, and the Browns would waste no time trying to get their picks under contract. “We’re having a staff meeting tomorrow [December 23] morning. We will make our assignments, and the assistant coaches will soon be on the hunt for signatures.”16 Brown would scout the Orange Bowl in Miami, Florida, on January 1. He and his family would spend much of the month of January in Miami vacationing.

NFL commissioner Bell expressed the hope that the failed conference in Philadelphia on December 20 would be the first of a series of meetings that would result in the sensible solution everyone was seeking to the war between the leagues. However, Bell repeated his position that peace would have to be made on the NFL’s terms. He also absolved Marshall of any blame for scuttling an agreement that might have otherwise been reached in Philadelphia.

For his part, Marshall didn’t see the war ending any time soon. “I don’t see any solution to this problem because [the AAFC team owners] are the type of men who go down with the thing. They are all nice fellows, but they don’t know how to operate a football business. They didn’t know a seven-team league won’t work.”17

The AAFC would find that out in 1949.

Before leaving for Florida and his combined scouting mission and vacation, Brown traded the negotiating rights to center Alex Sarkisian, a Cleveland draft selection, to the Yankees for tackle Derrell Palmer. Palmer played three seasons in New York and had been team captain in 1948. Dan Topping saw the deal as the first step in his quest to return the Yankees to the upper echelon of the AAFC, from which they’d slipped in 1948. New York’s 6–8 record was unacceptable to Topping, who was accustomed to both his baseball and football teams winning championships, or at least challenging for them.

“This is the first step to strengthen our club for the war the National League apparently wants,”18 said Topping. As usual, Brown knew exactly what he was doing. Palmer played in 55 games for the Browns through 1953, providing needed depth on the defensive line. Sarkisian never played for the Yankees, or any other team.

Topping’s Yankees were preparing to face more competition in 1949. Ted Collins had already announced his plan to relocate his Boston Yanks to New York. Collins said on December 23 that he’d soon meet with John Mara, the president of the New York Giants football team, and Horace Stoneham, the owner of the New York Giants baseball team, who’d be Collins’ landlord at the Polo Grounds. The purpose of the meeting would be to draw up a lease for the Yanks, and to arrange playing dates for 1949. The Giants, as long-time tenants, would undoubtedly get the prime dates, with the Yanks settling for the rest. When the Giants played the Yanks, it would have to be determined which team would dress in the home team’s locker room.

To avoid confusion, and to enable his team to forge its own identity in a city which was on the verge of hosting four professional football teams, Collins changed his team’s nickname to the Bulldogs. The baseball Yankees, football Yankees and football Yanks would have been a nightmare for sportswriters and broadcasters to keep straight.

In western New York, Jim Breuil reiterated his commitment to the AAFC and the city of Buffalo, which had supported the Bills well. “Professional football will stay in Buffalo,” he said before departing for Florida and a vacation on December 23. “Although our meeting in Philadelphia wasn’t successful, it pointed to a lot of success coming out of the meeting. I have no positive statements at this moment, because I don’t want to say anything that might hurt professional football, but I can say the pro game will stay in Buffalo.”19

The brief spark of hope inspired by the meeting in Philadelphia was all Eagles owner Alex Thompson needed to suggest that his team and the Browns should meet in a championship game. Thompson envisioned the large gate such a game figured to generate as a way to allow him to lessen, or possibly eliminate altogether, the financial loss he’d suffered in 1948 despite his Eagles’ NFL championship. The Browns were ready.

“For four years, coach Brown never said a word, he just kept putting that stuff on the bulletin board,” Otto Graham said years later. The “stuff” Graham referred to was newspaper clippings reporting the taunts from NFL owners and players, such as Marshall’s claim that the weakest team in the NFL would have no trouble defeating the Browns. “We were so fired up, we would have played them anywhere, anytime, for a keg of beer or a chocolate milkshake. It didn’t matter,”20 said Graham.

The opportunity didn’t present itself at the end of the 1948 season. Thompson was told by his fellow owners that a game between the Eagles and Browns was out of the question. The frustrated Thompson envisioned more red ink for 1949, regardless of how successful the Eagles were, so he sold the team and got out of football.

The Associated Press polled sportswriters in late December to determine which were the most important accomplishments of the year. The Cleveland Indians rise from fourth place in 1947 to the 1948 World Series championship, which included a victory over the Boston Red Sox in Fenway Park in the American League’s first one-game, winner take all pennant playoff, was voted the year’s top sports story. Second place went to the University of Michigan’s football team. The U.S. Olympic basketball team took third place. The undefeated AAFC champion Cleveland Browns were fourth. The Browns received 12 first place votes and 67 overall points.

After the flurry of activity in late December, all was quiet on the professional football front until January 11, when the United Press reported that Topping was willing, though not necessarily eager, to disband his football team and rent Yankee Stadium for use by Collins’ Bulldogs of the NFL if such an arrangement would result in the end of the football war.

The wire service quoted Yankees spokesman Red Patterson as saying Topping wouldn’t dissolve his franchise “if we would leave any of our associates holding the bag.” By associates, Patterson meant Topping’s fellow AAFC franchise owners. Patterson added that Topping “would do anything to bring about peace in pro football, and this would even include becoming a landlord at Yankee Stadium.”

The story, written by sports editor Bob Cooke of the New York Herald-Tribune, quoted an “authoritative source” as saying Topping was tired of “severe losses at the gate,” and that his decision to dissolve the Yankees “will no doubt inspire a new order in football. It is the considered opinion among professional football people that the two leagues can amalgamate in a happy manner if the case of the Baltimore Colts can be settled.”

According to a United Press story dated January 12, 1949, the Baltimore question was expected to be settled at a meeting of owners from both leagues one week hence, on January 19. The AAFC owners were scheduled to meet in Chicago on January 18, and the NFL owners would meet in the same city the next day. Although there was no formal peace conference scheduled, it was assumed that, with all of the owners of professional football teams in the same city at the same time, such a meeting would take place. At such a meeting, according to Topping, the NFL owners would have to put pressure on Marshall to drop his objection to sharing his territory with the Colts if peace was to be achieved. Topping said the vote for a merger among NFL magnates at the Philadelphia meeting in December had been 9–1 in favor, with Marshall casting the dissenting vote. And one dissenting vote was all it took to scuttle an agreement. The NFL’s by-laws required unanimous consent on matters of such importance.

“Pressure will have to be brought to bear on Marshall,”21 said Topping, simply.

The fate of the Browns was never in question. There was no concern among the Cleveland print media that the city might be without professional football in 1949 and beyond. If the AAFC and NFL remained separate entities, the Browns would conduct business as usual in 1949. If the AAFC merged with the NFL, the Browns would move into the older league. If the AAFC folded, the Browns would still move into the older league. Some NFL owners had objected to the transfer of the Rams to Los Angeles in January of 1946, and they were ready to welcome Cleveland back into the family. They wanted McBride’s team, and the huge facility it played in. Cleveland had led all of professional football in attendance for three consecutive years. McBride had a standing invitation to join the NFL whenever he decided to defect from the AAFC. But defecting wasn’t part of McBride’s game plan.

“I’m going to take the stand I’ve always taken,” said the Browns’ owner before the AAFC’s January 18 meeting. “That is that two leagues, working under a common agreement, like the major baseball leagues, is the healthiest thing for pro football.”22 At times, it seemed that McBride was on a one-man crusade to save the AAFC. Not all of his fellow owners were as dedicated to the young league as the Browns’ owner. He’d have to be quite persuasive to achieve his objective. At the January meeting, McBride would try to convince Branch Rickey to continue operating the Dodgers; to keep the Rockets in Chicago; and, failing that, to coax Morabito not to bail out of the AAFC. Morabito was on record as saying he wouldn’t operate the 49ers in a six-team AAFC. A six-team circuit would mean a 10-game season and only five home games for each team. Morabito estimated that two fewer games in Kezar Stadium would cost the 49ers as many as 80,000 paid admissions, and he wasn’t interested in that proposition.

The United Press story of January 12 speculated that the peace conference which hadn’t officially been scheduled would result in a 14-team NFL. The Yankees, Dodgers and Rockets would disband, and the Dons and Rams would merge, leaving Los Angeles with one team. There would be two seven-team divisions. McBride didn’t see that happening. In fact, he didn’t think there’d be a merger of any kind, because he couldn’t imagine Marshall consenting to one.

“Marshall is pretty strong in the National League,” said McBride. “He wields a lot of influence. I can’t see him backing down now.”23 As a precursor to the league meetings, the United Press reported that Lindheimer and Reeves had met twice to discuss merging their teams into a single unit. Colts president Robert Embry said he hoped to arrange a meeting with Marshall to talk about the Redskins owner’s objections to the presence of a team in Baltimore.

The official agenda, as released to the news media, for the AAFC owners meeting on January 18 mentioned nothing about a discussion of peace talks with the NFL. The owners would talk about a TV contract, roster sizes for 1949, the possibility of mid-week games (a cause championed by Rickey), election of officers, and consideration of applications for new franchises and applications to relocate existing teams. The Browns were represented by McBride, his son Arthur Junior, Paul Brown, Dan Sherby and minority stockholder Bob Gries.

A spokesman for the NFL said the agenda for his league’s owner’s meeting had no provision for a discussion of peace talks with the AAFC.

In the January 19 edition of the Press, Bob Yonkers told his readers the demise of the AAFC was imminent. Unless new owners could be found for the Rockets, the AAFC would fold. And finding new ownership for the league’s weakest franchise figured to be a daunting task since, according to McBride, “this time all owners will have to guarantee in writing that they’ll be able to meet their obligations.” That was a reference to the failure of the ownership group that took control of the Chicago franchise after the 1947 season to come up with the capital to keep the team going in spite of heavy losses in 1948. McBride, Morabito and Topping had to ante up $100,000 between them at mid-season to keep the Rockets from folding. They had no intention of bailing out any more bankrupt franchises.

Lindheimer, the owner of the Dons, lived in Chicago and was reportedly willing to buy the Rockets, if he could swap them for the Dons and move the Dons to Chicago. The AAFC wanted a franchise in Los Angeles, and no one in southern California was expected to come forward to buy the putrid Rockets and exchange venues with Lindheimer. Thus, that plan appeared to be doomed to failure.

Yonkers wrote that the Dodgers had lost $319,000 in 1948. Rickey personally absorbed 25 percent of the loss, or roughly $80,000. Brooklyn would be dropped if the AAFC disbanded. The Colts would pay Marshall $200,000 for invading his territory, and Ted Collins would fork over $150,000 to the Mara family for moving his Boston Yanks to New York, where they’d play in Yankee Stadium, which Collins would lease from Topping.

The Press also reported that the Dodgers planned to cut the salary of quarterback Bob Chappuis, whom the newspaper called professional football’s “bust of the year” for 1948, from $30,000 to $12,000. It was an odd note since, on the same page, the newspaper’s football correspondent had spent several paragraphs detailing the end of the AAFC, and with it the Brooklyn club.

On January 20, Yonkers reported that the death of the AAFC was not at hand. Instead, Lindheimer had breathed new life into the league by agreeing to purchase the Rockets. The sale of the Dons would be worked out at a later date. In an effort to strengthen their team in the league’s second-largest market, Lindheimer’s fellow owners agreed to make some of their players available to the Rockets, much as the AAFC, at commissioner Ingram’s suggestion, had done after the 1947 season to strengthen the Rockets and Colts. Unlike 1947, however, the players wouldn’t be given away. Lindheimer would have to pay to acquire them.

Being a Chicago resident, Lindheimer could save $60,000 on operating expenses by moving the Rockets’ headquarters into space he already leased in the Chicago Board of Trade building. The two race tracks Lindheimer owned used the space and had plenty to spare for his new football team.

It also appeared that the AAFC would retain a team in Brooklyn. In order to convince Rickey not to throw in the towel, the owners agreed to waive the league’s mandatory $15,000 guarantee to visiting teams when the league’s biggest draw, the Browns, played at Ebbets Field. McBride was willing to make that concession to keep Brooklyn in the league. Rickey also wouldn’t be required to hand over at least $15,000 to the 49ers, Yankees, or Dons when they visited Brooklyn. Hopefully, a better product on the field in 1949 would mean bigger crowds, and with smaller guarantees to be paid to the visiting team, Rickey could keep more of the gate receipts for himself. If that didn’t result in the Dodgers turning a profit, it should have at least cut ownership’s losses.

The announcement that the AAFC had been saved didn’t impress, or even convince, Tim Mara or George Preston Marshall. At the NFL owners meeting across town, both men insisted the AAFC was bluffing and would soon go out of business. The announcement of Lindheimer’s purchase of the Rockets, and the proposal to Rickey to keep football in Brooklyn, was made to try to bring the NFL to the peace table, and secure better merger terms for the AAFC, in the opinion of Marshall and Mara.

Said Rams owner Dan Reeves of a possible peace agreement, “It will be good for everybody, but I don’t think it will come.”24

The hiring, or rehiring, of commissioners was on the agenda of both meetings. The NFL signed Bert Bell, a former owner and coach, to a 10-year contract at an annual salary of $30,000. Looking to save money as the war for playing talent dragged on, the NFL owners reduced their rosters from 35 to 32 players for 1949. And, perhaps as a slap at their AAFC counterparts who’d reduced the guarantee the Dodgers would be required to pay most visiting teams, the NFL increased its mandatory payout to visitors from $15,000 to $20,000.

As he had vowed to do at the owners’ meeting in Cleveland in December, Ingram stepped down as commissioner of the AAFC at the January 18 meeting. “I’d like to step out today,” said the outgoing commissioner. “I have sickness in my family, and haven’t been too well myself, and it is a hardship for me to get around the country. I’m definitely through with professional football. Now that we have set this thing up to operate another year, I think they should get a new and younger man to carry on from here. There are no weak links in the chain as it stands today.”25

Ingram was replaced by the league’s deputy commissioner, Oliver Owen Kessing. Like Ingram, Kessing had been a naval officer and had planned to depart along with Ingram. Instead, the owners made him an offer he couldn’t refuse. He was signed for one-year at the same salary Bell would earn: $30,000.

“I am deeply appreciative of the honor and will do all in my power to preserve the strength and integrity of the All-America Conference,”26 promised the league’s new commissioner.

Said Paul Brown of the choice of Kessing to replace Ingram, “We simply felt he knows our business and our problems. Kessing is a likable fellow, and I am confident he will be a good commissioner.”27 Perhaps to save money, or perhaps because the owners had no viable candidate for the job, the position of deputy commissioner vacated by Kessing would not be filled. Kessing was also voted league president. Topping was elected vice president, Embry treasurer, and league attorney Louis Carroll was elected secretary.

While the owners were meeting, and commissioners were being appointed, and the fates of leagues (and the players who toiled in them) were being debated, more mundane football business was still being conducted. AAFC public relations director Joe Petritz announced on January 17 that six teams had signed 46 new players for the 1949 season. The teams, and the players, weren’t identified.

On January 8, Otto Graham had been honored by the Washington, D.C., Touchdown Club as the AAFC’s most valuable player. The same honor in the NFL was bestowed on Philadelphia Eagles running back Steve Van Buren. The two MVP’s undoubtedly commiserated as to how they would like to have met on the field of play to determine which league’s champion was better.

Eagles owner Alex Thompson would’ve liked that, too. Soon after vowing to fight the AAFC to the death, Thompson decided he’d had enough of pro football. His Eagles had lost money despite winning the NFL championship, and a chance to recoup some of that lost money via a championship game against the Browns was vetoed by Thompson’s fellow NFL owners. McBride and the Browns would have been glad to meet the Eagles anywhere, anytime, with the blessing of the rest of the league, but the majority of the NFL owners wouldn’t permit such a game. Aside from a financial windfall, the NFL had nothing to gain and everything to lose. A frustrated Thompson sold the Eagles to a syndicate of 100 Philadelphians, led by businessman and former city Democratic party chairman James Clarke, on January 15. The purchase price was $250,000. The sale was applauded in Philadelphia for restoring local ownership to the Eagles. Thompson lived in New York City.

The New York Bulldogs struck a blow for the establishment when they signed hotshot college quarterback Johnny Rauch from the University of Georgia in mid–January. Despite the fact he claimed to have lost nearly three-quarters of a million dollars on his football team while it played in Boston, Ted Collins found the cash to sign Rauch to a three-year deal worth $17,000 per season. As a bonus, Rauch received $3,000 and a car for signing.

Another blow for the NFL was struck when All-American guard Bill Fischer from Notre Dame chose the Cardinals over the Browns. Fischer signed a three-year contract worth $8,000 per season, and the Bidwill family gave him an extra $5,000 as a signing bonus. Fischer had reportedly been heavily influenced by his fiancee, who was from Chicago (as Fischer was) and preferred to stay there rather than move to Cleveland. The future Mrs. Fischer proved to be more persuasive than McBride’s money or Paul Brown’s charm.

Otto Graham tried to follow in Paul Brown's footsteps. He was head coach at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy and spent three seasons coaching the Washington Redskins.

It had been a while since a rumor had circulated about Brown abandoning the pros for a college job. On January 15, Dr. Walter Beggs, chairman of the University of Nebraska’s athletic board, said he’d be happy to interview Brown if Brown was interested in the school’s head football coaching vacancy. He wasn’t. The Brown-to-UCLA rumor died on January 20 when Henry (Red) Sanders was hired to replaced Bert LaBrucherie, who’d resigned in December. Sanders had been head coach at Vanderbilt University before accepting the Bruins’ job.

In early January, the Dons had given the AAFC a black eye when they dismissed assistant coaches Mel Hein, Ted Shipkey and Earl Martineau. General manager Harry Thayer admitted the coaches were fired to cut the team’s budget, and the NFL never missed an opportunity to point out when the AAFC resorted to austerity measures. Thayer quickly back-tracked and said Hein, Shipkey and Martineau weren’t dismissed to save Lindheimer money, but because head coach Jimmy Phelan wanted to choose his own assistants.

Money wasn’t the AAFC’s problem, according to Press sports editor Whitey Lewis. “Don’t get the opinion the AAC or its individual club owners are short of cash,” Lewis wrote on January 21, as it appeared the prospects for peace had evaporated and the AAFC-NFL confrontation was destined to drag through the 1949 season. “The AAC is probably sounder than the National League. The latter has all the heritage, but it lacks fast men with a free buck.” In addition to owners McBride of the Browns, Lindheimer of the Dons, Breuil of the Bills and Topping of the Yankees, millionaires all who didn’t depend on football for their incomes, one of the many stockholders in the Baltimore franchise was local businessman Jerry Hoffberger, reported to be the richest person in Maryland. Morabito of the 49ers was said to be well-off financially, but not quite as rich as the aforementioned owners. That may explain why Morabito didn’t want a six-team AAFC that would cost his team two home games per season. He needed that revenue.

Although Bert Bell had just been given a 10-year deal as commissioner of the NFL, Lewis claimed many of the older league’s owners were weary of Bell’s strong backing of Mara and Marshall on matters pertaining to a merger. Mara and Marshall were easily able to weather the financial storm resulting from the competition between the two leagues, and Lewis said many other owners, who made their money from football, were tired of incurring losses because of the stubbornness of the owners of the Giants and Redskins. The columnist even posed the question of who was actually running the NFL, Bell or Marshall? The answer was implicit. Lewis believed Marshall was calling the shots.

Mara, Marshall, and the rest of the NFL owners found out the AAFC wasn’t bluffing about the 1949 season. Before both sides adjourned their winter meetings, McBride made one last-ditch effort to bring the costly skirmish between the two professional football leagues to an end. In Chicago, McBride met with eight NFL owners and proposed moving forward in 1949 with two seven-team leagues. Mara and Marshall, as always, were opposed. The owners who favored McBride’s idea urged him to ask for an audience with commissioner Bell.

“My door has been open right along,” Bell said. “I’d be glad to talk with them at any time.”28 But McBride rejected the idea as a waste of time. He believed Bell was nothing more than Marshall’s mouthpiece. “I gave it a lot of thought, and decided to recommend going along by ourselves under the seven team set-up. I don’t think we would have gotten very far by sending someone to see Bell.”29 McBride said there was still plenty of lingering bitterness among the AAFC owners after the way they felt they’d been disrespected by the NFL at the meeting in Philadelphia in December.

“Everyone is plenty disturbed about what happened in Philadelphia,” he said after the AAFC announced it would forge ahead with seven teams (minus Brooklyn) in 1949. “We’re all more determined than ever to carry on now.”30 Even Morabito who, according to an Associated Press story, met with Marshall in Chicago to discuss unilaterally moving the 49ers into the NFL. That would have given the Rams a much-needed west coast rival. Morabito’s attorney attended that meeting, in the event there were legal matters to be taken care of, but nothing came of it.

Nor did anything come of a meeting between a number of unidentified AAFC owners and George Halas. The owner of the Bears was tight-lipped about the gathering, saying only that he was convinced all hope of an agreement between the two leagues had evaporated. He was right. Meetings, and more meetings, and rumors of meetings, had produced only new ownership for the AAFC’s Chicago franchise and a merger between the New York Yankees and Brooklyn Dodgers. Lindheimer said he’d lined up $300,000 in financing for the Rockets for 1949. And since the Yankees weren’t going to fold, Topping wasn’t going to lease his stadium to Collins. The Bulldogs would have to share New York’s Polo Grounds with Mara’s Giants. The Giants would get scheduling priority.

Paul Brown assessed the accomplishments of the AAFC owners meeting by saying, “We have done what we think is best for the future of American professional football. It is our belief there should be two leagues. We have emphasized making Chicago and New York strong in this move, and though we will have fewer games, better attractions should keep up the interest and increase attendance. We believe we [will] ultimately reach the goal for which we have been aiming.”31 That goal was two separate but equal football leagues, operating under one agreed upon set of rules, which would include a common draft. The champions of those two leagues would meet in a one-game, winner-take-all playoff at the conclusion of each season. The same kind of arrangement the National and American baseball leagues had operated under since 1903, except for the player draft, which wouldn’t come along until 1965.

For the 1949 season, the AAFC and NFL would remain separate, but not equal. And rumors of an inevitable end to the professional football war would continue to swirl. In each rumored scenario, the AAFC came out on the short end.

In the eternally confused, and confusing, world of the All-America Football Conference, it was announced on January 29 that Lindheimer had not purchased the Rockets. He had, however, lined up three backers who pledged to invest $300,000 in the team. Those backers were introduced as 52-year-old banker James Thompson, who was providing most of the cash to (hopefully) rejuvenate the Rockets; Lee Freeman and Irvin Rooks. Freeman and Rooks were described as attorneys and public utilities executives.

The purpose of the meeting at which the new Chicago financing arrangements were explained was to give the other team owners a chance to make good on their promise to provide players to improve the Rockets. Twenty-six members of the defunct Dodgers would be transferred to the Rockets, among them quarterback Chappuis, halfback Hunchy Hoernschmeyer, ends Hank Foldberg, Dan Edwards and Max Morris, and center George Strohmeyer. In addition, halfback Bob Schweiger of the Yankees had been sent to Chicago. It was fervently hoped by the AAFC (and the new owners of the Chicago club) that an amalgamation of players from two terrible teams (the Rockets had been 1–13 and the Dodgers 2–12) would produce one competitive team.

“Let’s have a helluva good team in Chicago, and then worry about peace with the National League,”32 said Thompson upon his introduction to the news media. Asked how much he knew about the team he was taking financial control of, Thompson admitted he hadn’t even known where the Rockets’ office was until the previous day.

On the same day the saviors of AAFC football in Chicago were introduced, former Rockets head coach Dick Hanley, who served for the first three games of the 1946 season, filed a lawsuit in superior court, seeking the $38,750 in salary he was owed. Commissioner Kessing said it was a problem for Hanley and John Keeshin, the team’s first owner, to haggle over between themselves. The AAFC wanted no part of it.

Seeking a fresh start, the Rockets changed their nickname to Hornets and hired Ray Flaherty as head coach. Paul Brown hailed the move and said he looked forward to once again matching wits with his esteemed nemesis. Brown had been denied that chance in 1948, when Flaherty was fired by the Yankees before the two teams were scheduled to meet. Flaherty coaxed an improved performance from the Chicago team, but even a Hall of Famer couldn’t make a silk purse from a sow’s ear, and the Hornets remained AAFC doormats at 4–8. At least the few people in Chicago who cared about their AAFC team didn’t have to watch it as often in 1949. The Hornets played only four games in Soldier Field and eight on the road. Attendance was 83,708, an average of 20,927 per game. That represented an improvement of roughly 6,000 per game over the Rockets’ 1948 average of 14,857. The Bears, with a record of 9–3, drew 262,946 to their six games in Wrigley Field. The Cardinals, at 6–5–1 slipping back toward the mediocrity from which they’d temporarily emerged in 1947 and `48, attracted 172,444 to their six games in Comiskey Park. The Cardinals were without head coach Jimmy Conzelman, who’d taken them to the NFL title games the previous two years, winning the championship in 1947. Conzelman resigned after the 1948 season, reportedly because the team was in dire financial straits, and he was concerned about getting paid if he fulfilled the final year of his contract. Some 52,000 had attended the Cards’ home game with the Bears. It was easily their largest home crowd of the year, and represented 30 percent of their total attendance for the season.

How serious had the rumors been about Brown turning his back on the chaotic AAFC and returning to college coaching? Serious enough that McBride felt it necessary to extend his head coach and general manager’s contract by five years on January 31. Brown’s original contract ran through the 1950 season. His new deal ran through 1955.

After signing, Brown confessed that, in spite of his repeated denials, he had been approached about a number of college coaching positions in 1948. And he had seriously considered those offers. “I had to make up my mind, because several schools were pushing me for a decision,”33 he said. His decision was to stay in Cleveland.

“I’m not saying we’ll have a championship team for the next seven years,” said McBride. “But as long as Brown is coaching our club, I’m sure we’ll finish at least one-two-three.”34

Despite the failure of negotiations between the two leagues in both December and January, Brown said he was confident about the future of professional football in general. “All signs point to peace in the near future. I’m not sure it will come about before the 1949 season, but as time goes on, more and more people in the National League seem to be sharing our views regarding a working agreement.” Whether Tim Mara and George Preston Marshall could be brought around to the Browns’ way of thinking remained to be seen.

“My family and I have learned to like Cleveland and its people,” said Brown of his decision to stay with the team he started and that bore his name. “I like pro football and am very happy to remain in it. I only hope that in the next seven years, I can do all in my power to make the sport an institution here—prove to everybody we have the best interests of the sport uppermost in our minds.”35 The Browns would become a Cleveland institution, just as Brown hoped they would, and he was largely responsible for that.

In spite of McBride’s wealth and Brown’s unprecedented accomplishments, he didn’t receive a raise in salary. He signed for the same deal he’d agreed to in 1945, an annual salary of $25,000 and 15 percent of the team’s profits. When there was a profit to be shared.

Even though they’d led all of professional football in attendance in 1948, with the league championship game thrown in, the Browns lost money. According to McBride, his team lost $35,000 in 1948. It was a relatively small amount compared to the bundles of cash most other teams had lost. McBride estimated that among AAFC teams, only the 49ers had made a profit, and they put a mere $3,000 in Morabito’s bank account.

McBride claimed, without providing any documentation, that the Dons had lost $250,000 in 1948, followed by Buffalo and Chicago at $100,000; Topping’s Yankees lost $50,000; and the publicly-owned Colts dropped $43,000. In the NFL, McBride said Ted Collins had lost $300,000 on his Boston team; the Rams had lost $250,000 (meaning the two Los Angeles teams had watched half a million dollars go down the drain); Mara had lost $200,000 on the Giants; the Packers, in professional football’s last remaining small town, had lost $150,000; Detroit’s loss was $93,000; Pittsburgh’s was $70,000. The Cardinals and Eagles each lost $40,000. Marshall’s Redskins had broken even, and Halas’ Bears turned a tidy profit of $50,000. If McBride’s estimates were accurate, the owners of the 15 professional football teams which lost money in 1948 were drowning in $1,668,000 worth of red ink.

McBride, Lindheimer, Topping and Breuil in the AAFC were millionaires who could stomach their losses. But how long would they be willing to throw good money after bad in exchange for the fun of owning a major league football team? Especially since the Browns were draining most of that fun from the AAFC owners not named McBride?

With only seven teams, the AAFC reduced its schedule from 14 games to 12. The eastern and western divisions were scrapped. Instead of the division champions meeting in the title game, the four teams with the best records would qualify for the playoffs. The number one seed would host the number four, and the number two seed would host the number three, with the winners meeting for the championship on the field of the higher seeded team. It marked the first time in pro football history that home field advantage was earned by the teams with the best records, a practice the NFL wouldn’t adopt until the 1974 season.

The Browns would finally lose a game in 1949. Their 18-game winning streak, which began with a 27–17 victory over Los Angeles on November 27, 1947, and included a pair of championship game victories, ended with the opening game of the 1949 season. The game was a rematch of the 1948 title game, and the Bills secured a measure of revenge for their embarrassing, 42-point drubbing, by holding the Browns to a 28–28 deadlock. Cleveland’s professional record 29-game unbeaten streak came to a screeching halt five weeks later in Kezar Stadium. The 49ers took out three years of frustration on their tormentors with a 56–28 bombardment on October 9, before a giddy, sell-out crowd of 59,720. The defeat so enraged Brown that he threatened to gut his champions and start all over if they didn’t regroup the following Sunday in Los Angeles. It was a threat Brown couldn’t have carried out, but it had the desired effect. The Browns buried the Dons, 61–14. Cleveland wouldn’t lose another game in the AAFC. Its 9–1–2 record secured the top seed in the league’s four-team playoff, and home field advantage throughout the post-season. The home team would win all three playoff games.

The Browns defeated the fourth-seeded Bills, 31–21, in one semi-final. The 49ers beat the third-seeded Yankees in San Francisco in the other, 24–7. Two days before the championship game, the “sensible solution” to pro football’s four-year problem was reached. The Browns, 49ers and Colts would join the NFL in 1950. The remaining AAFC teams would be disbanded, and their players dispersed among the 13 NFL clubs. With the exception of the Colts being admitted to the NFL (and their stay would be brief), the terms were essentially the same as the NFL had insisted upon at the ill-fated Philadelphia meeting in December of 1948.

The last AAFC game was played in Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium on Sunday, December 11, 1949. In the same stadium three years and three months earlier, a crowd of 60,135 had watched the Browns inaugurate the new league with a 44–0 victory over the Miami Seahawks. Twice throngs of better than 80,000 had cheered the Browns in Municipal Stadium. But the AAFC’s final game drew just 22,550 spectators. They watched the Browns win for the 52nd time, against only four defeats and three ties. They polished off the 49ers, 21–7. The AAFC was officially kaput. The Browns were the only champions Arch Ward’s league ever crowned.

In the final analysis, that was probably why the AAFC failed. Brown’s Browns were just too good.