On a sunny December afternoon in 1945, three brothers were gathering soft dirt from a remote cliff side in their native Egypt when one of the brothers, an Arab peasant named Muhammed ‘Ali al-Samman, unexpectedly struck something hard in the earth. In growing astonishment, he excavated the object, a large red earthenware jar nearly six feet in height, buried in the sandy soil. When he broke it open, Muhammed was at first dismayed to see that the jar contained leather-bound papyrus books of obvious antiquity. Overcoming his disappointment and sensing the possible value of his find, he and his brothers trundled the thirteen antique books back to their village. So begins a remarkable modern-day saga—the rescue, retrieval, and eventual revelation of a gnostic library, a body of literature buried in the late fourth century in a dry riverbed near the Egyptian town of Nag Hammadi by unnamed monks eager to save the teachings of their persecuted sect. Scholars speculate that the codices might have been interred following a ban placed on them by Athanasius, the Christian archbishop of Alexandria, in 367. Another possibility is that the documents were hidden several decades earlier to protect them from destruction by Monophysites, a sect of Christians who claimed that Jesus had only divine nature, not physical.1 Following instructions given to the Hebrew prophet Jeremiah to preserve a document in an earthenware jar, enterprising monks hid the thirteen most valuable books from their library in the clay jar, and the isolated desert terrain successfully preserved the documents for nearly sixteen hundred years.

Since the accidental discovery of this literary treasure in 1945, scholars have been poring over the documents, translating and interpreting the difficult—often damaged—texts, eagerly searching their depths for the wisdom of gnostic sectarians driven out of Christian congregations by stern decrees of the orthodox priests and bishops who declared the gnostic teachings heretical. These recovered codices have been invaluable, casting new light on the diverse beliefs and the struggles of early Christians to establish creeds that could be held in common by the entire community of believers. Whereas orthodox priests insisted that belief in Jesus, baptism in his name, and obedience to his priests was sufficient for salvation, gnostics believed that salvation was a soul’s journey toward spiritual enlightenment under the direct inspiration and guidance of the risen Jesus Christ, through the action of the Holy Spirit. For these sectarians, the goal of the Christian was to encounter the Christ on a spiritual plane rather than to profess belief in a memorized creed. Struggles over doctrines of Christology and interpretation of scripture continued for more than three centuries in Egypt and the Middle East before gnostic sects were officially forced out of mainstream Christianity and into exile, relentlessly driven out by neighbors who cast rocks at them as they fled.

The collected wisdom of one monastic community was bound into leather covers and hidden in the red clay jar at the foot of the Jabal al-Tarif. Their voices were silenced and their teachings eventually sank into the desert sands and were channeled into an underground stream, later reemerging in Western Europe to water the seeds of the Renaissance—nurturing the rebirth of an ancient wisdom tradition after long centuries of exile. In the interim years, we must rely on the polemic of their adversaries for hints about the tenets of their faith.

One allegation leveled against gnostic Christians was that they relied on numbers theology to interpret scripture, supporting the theory that gnostic sectarians were aware of the universal wisdom of the Pythagorean School of philosophy. Initiates of the schools studied secret doctrines, including the canons of sacred geometry that expressed cosmic principles as numbers. Powerful evidence of Pythagorean influence is found in the gematria of classic literature and of Judeo-Christian sacred texts. A few New Testament scholars are now addressing the issue of symbolic numbers found in scripture and their astonishing implications. Unfortunately for the integrity of New Testament scholarship, a number of Christians, even in our enlightened age, attack this fascinating field of study, giving it a negative spin by branding it “numerology.” Gematria is not numerology and is not used for divination. It is, rather, a historically verified literary device used to enhance the impact of a name or phrase by deliberate association with the symbolic number of the cosmic principle it manifests. Both Hebrew and Greek alphabets attach numeric values to each letter, and both the Hebrew Bible and the Greek New Testament—gospels, Epistles, and Book of Revelation—are replete with phrases enhanced by gematria.2 Instead of setting the passages of their most important sacred texts to music, our ancestors set them to number.

Magdalene, Favorite Disciple

For scholars studying the long-hidden gnostic texts, one of the most startling revelations of the Nag Hammadi library has been the high esteem in which Mary called the Magdalene was held among adherents of several persecuted sects who authored the rejected gospels and treatises. Hints of the honor in which Mary Magdalene was held among early communities of Christians first surfaced in the late nineteenth century with the publication of the gnostic Gospel of Mary and a Valentinian gnostic text entitled Pistis Sophia. Devalued and vilified in a Western European tradition that branded her a prostitute, the preeminent female saint emerges from these and several other gnostic documents as the favored and most beloved of all the disciples of Jesus, his closest and dearest companion, and even his consort and counterpart. Although only a few gnostic texts mention Mary Magdalene at all, none associates her with a common harlot or prostitute. Instead, she is characterized as the favorite disciple of the Lord and, in one gospel, as his intimate companion. In several of the suppressed texts, the male disciples and apostles are clearly jealous of Jesus’ intimacy with Mary Magdalene; they cannot understand why the Lord would share esoteric teachings with her that he did not share with them.

This resentful attitude of the male apostles toward Mary Magdalene reflects the prevailing mind-set of their late-second-and third-century milieu—the belief that men were important citizens and that women existed to serve men in a role that was inferior. In a notable passage found near the end of the gnostic Gospel of Thomas, Jesus states that he will make Mary an anthropos. Sadly, the Greek word anthropos in this text has been widely misunderstood to mean “male,” though it might be more accurately translated as “perfected human being,” in the sense of a complete or realized, fully human person.3 In this passage, Jesus promises not to make Mary masculine in gender, but rather to transform her into a perfected spiritual being whose gender is irrelevant. In his time and milieu—first-century Judaism where men and women worshipped in separate venues and men thanked God during morning devotions that they were not “born a woman”—the mere idea of a woman as a spiritual being equal to a man was a radical departure from convention, but it was one of the hallmarks of early Christianity.

We cannot tell for certain whether the gnostic texts reflect accurately a tradition of physical intimacy between Jesus and Mary Magdalene and his preference for her over his other apostles, but the tradition itself is irrefutable, based squarely on the witness of the canonical gospels that style the two as beloveds. We have only to consider their repeated testimony that Mary Magdalene was more faithful to Jesus than were Peter and the other male apostles named as the twelve. She remains near Jesus throughout his agony on the cross. She is present at his deposition and interment and present again in the garden on Easter morning, where she comes as a close family member to perform the ritual anointing of the deceased, along with his mother and aunt (or sister) Salome (Mark 16:1). Perhaps the gnostic texts extolling her spiritual enlightenment merely reflect this universally accepted tradition of Mary Magdalene’s ardent devotion to Jesus, which earned her the unique privilege of first witness to the resurrection. On this basis alone, proclaiming her the beloved or favorite disciple would be justified.

The gnostic Gospel of Philip carries testimony of the special relationship between Jesus and the Magdalene much further, attesting to a relationship of surprising intensity—of which the male disciples were demonstrably jealous: “The partner of the Savior is Mary

Magdalene.”4 The Greek/Coptic

koin nos can also be translated as “spouse,” “consort,” or “companion” as well as “partner.”

nos can also be translated as “spouse,” “consort,” or “companion” as well as “partner.”

On several occasions in the suppressed texts, Peter complains that Mary Magdalene appears to have received special, secret teachings from Jesus. In the Gospel of Mary, Peter is rebuffed by Levi, who defends Mary: “Yet if the Teacher found her worthy, who are you to reject her?”5 Levi continues, asserting that Jesus “knew her very well, for he loved her more than us.” In examining these texts, we find the two major protagonists, Peter and Mary, represent two distinct approaches to the good news of the Christian story. While Peter grasps the fundamental tenets of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus, holding them as historical facts of which he is the designated chief guardian, Mary is in constant communion with the risen Christ—the recipient of ongoing revelation directly communicated heart to heart: “[F]or it was in silence that the Teacher spoke to her.”6

The third-century text of the Gospel of Philip refers to Mary Magdalene as the koin nos—the intimate companion or consort—of the Savior and goes on to relate that the apostles were jealous or disapproving of her because Jesus kissed her often. Although the text is damaged so that we cannot determine exactly where Jesus kissed her—whether on the cheek, forehead, lips, or shoulder—the text implies that he kissed her on the mouth, because the other apostles were affronted

by this frequent intimacy. They ask Jesus why he loves Mary more than he does them and his answer implies that they are spiritually dense while Mary is enlightened. Obviously, from statements found in this gospel and in the gnostic tract Pistis Sophia, Mary is seen as the most spiritually enlightened of the disciples surrounding the Savior. Surprisingly, she is not called the Magdalene in any of the gnostic gospels except in the Gospel of Philip. The woman referred to as the “other Mary” is identified as the mother of Jesus, and Mary Magdalene is simply called Maria or Miriam and “the blessed one.”

nos—the intimate companion or consort—of the Savior and goes on to relate that the apostles were jealous or disapproving of her because Jesus kissed her often. Although the text is damaged so that we cannot determine exactly where Jesus kissed her—whether on the cheek, forehead, lips, or shoulder—the text implies that he kissed her on the mouth, because the other apostles were affronted

by this frequent intimacy. They ask Jesus why he loves Mary more than he does them and his answer implies that they are spiritually dense while Mary is enlightened. Obviously, from statements found in this gospel and in the gnostic tract Pistis Sophia, Mary is seen as the most spiritually enlightened of the disciples surrounding the Savior. Surprisingly, she is not called the Magdalene in any of the gnostic gospels except in the Gospel of Philip. The woman referred to as the “other Mary” is identified as the mother of Jesus, and Mary Magdalene is simply called Maria or Miriam and “the blessed one.”

Because a kiss suggests a sharing of breath, a kiss unites two people in an intimacy both physical and spiritual. Jean-Yves Leloup, a mystic and scholar who has translated several gnostic gospels, including the Gospel of Philip and the Gospel of Mary, suggests that the body of gnostic literature buried near Nag Hammadi was hidden to protect it from destruction precisely because it portrayed physical intimacy between Jesus and Mary Magdalene, culminating in the bridal chamber of sexual union.7 The physical nature of Jesus was attacked by Docetic and Monophysite sects whose adherents denied Jesus’ full humanity, holding that he was a purely spiritual being, while the orthodox insisted that Jesus came in the flesh, declaring, “Every spirit that confesses that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh is of God” (1 John 4:2). Mainstream Christians believed in an actual, historical, and very human Jesus whose legacy of teachings they celebrated, “like unto us in all things but sin.”

The issue of Jesus’ full humanity is clearly stated in the Gospel of Philip, where the Savior is uniquely presented as the seed of Joseph the

Carpenter,8 a statement that ignores any hint of the virgin birth but acknowledges the genealogical passages found in Matthew and Luke that Jesus was the son of Joseph. According to the inspired analysis of Jean-Yves Leloup, the Gospel of Philip is not just about the holiness of spiritual communion; rather it expresses the sacred nature of the physical union of a man and woman, the mystery of the bridal chamber, as an expression of God’s presence. The author of this apocryphal gospel calls Mary Magdalene the koin nos of Jesus and later in the text uses a word derived from the same root, koin

nos of Jesus and later in the text uses a word derived from the same root, koin nia, translated as

“mating.”9 Although other biblical texts, including the canonical epistles in the New Testament, translate the word koin

nia, translated as

“mating.”9 Although other biblical texts, including the canonical epistles in the New Testament, translate the word koin nos to mean “companion,” in the sense of a friend, the word carries a more intimate meaning, with sexual connotations, for the author of the Gospel of Philip. Leloup apparently feels that the central theme of this gospel was the full humanity of Jesus and that his intimacy with Mary Magdalene was an expression and proof of this

fullness.10 Leloup suggests that a primary theme of the Gospel of Philip is “the union of man and woman as revelation of the Love of creator and

savior.”11 Further, he maintains that the sexual act belongs to the divine realm—a “theophany,” or revelation, of

God.12 For Leloup, these themes in the Gospel of Philip reflect long-held Jewish traditions about the holiness of sex and procreation and the complementary essence of masculine and feminine. Among apocryphal texts of gnostics who allegedly denied the flesh and viewed the physical world as the corrupt creation of an inferior god they called the Demiurge, the Gospel of Philip, with its emphasis on the holiness of the marriage act, appears to be an anomaly.

nos to mean “companion,” in the sense of a friend, the word carries a more intimate meaning, with sexual connotations, for the author of the Gospel of Philip. Leloup apparently feels that the central theme of this gospel was the full humanity of Jesus and that his intimacy with Mary Magdalene was an expression and proof of this

fullness.10 Leloup suggests that a primary theme of the Gospel of Philip is “the union of man and woman as revelation of the Love of creator and

savior.”11 Further, he maintains that the sexual act belongs to the divine realm—a “theophany,” or revelation, of

God.12 For Leloup, these themes in the Gospel of Philip reflect long-held Jewish traditions about the holiness of sex and procreation and the complementary essence of masculine and feminine. Among apocryphal texts of gnostics who allegedly denied the flesh and viewed the physical world as the corrupt creation of an inferior god they called the Demiurge, the Gospel of Philip, with its emphasis on the holiness of the marriage act, appears to be an anomaly.

The evident rivalry between Peter’s way and Mary’s is rooted in the psychology of masculine and feminine and in the dualism of left-brain, right-handed or Logos orientation in opposition to right-brain, left-handed intuitive ways of relating to reality. Peter, the Rock, represents the orthodox version of Christianity, the vessel or bark of Christians who memorize creeds and catechisms and are awarded safe passage to paradise through the mediation of hierarchical priests with absolute authority over their lives and souls, to whom they owe honor and strict obedience. Mary’s is the way of the heart—compassionate relationship with the Divine and with creation. In doctrines of the orthodox, Peter holds the keys of the kingdom. What he binds on earth is bound in heaven. These familiar tenets of institutional Christianity are derived from passages in the canonical gospels originally accepted by Bishop Irenaeus and later Church fathers in the third and fourth centuries. The patriarchs concluded that these contained authentic teachings of Jesus, based on what they believed to be eyewitness testimony of two apostles—Matthew and John—and of two other authors, Mark and Luke, who they believed were direct disciples of Peter and Paul, respectively. Modern scholarship has determined that, in all probability, not one of the accepted gospels was written by an eyewitness, but among early Christians, the four gospels were widely accepted as authentic accounts of Jesus’ life and ministry. Delegations of priests later created the Christian creeds and established doctrines accepted at various church councils during the early Christian era, gradually solidifying and institutionalizing what had begun as a spontaneous movement honoring the memory of the charismatic rabbi Yeshua, his wisdom teachings, and his Way of reconciliation.

An important legacy of the gnostic view of Mary Magdalene is their image of her as the human incarnation of the Sophia, or Feminine Consciousness. Citizens of the power-drunk Roman Empire—both Jewish and Gentile philosophers—saw that the honor once paid to the goddess Wisdom/Sophia had been superseded by solar and warrior cults of the gods Apollo and Mithras, as well as by various forms of emperor worship. In The Wisdom of Solomon, a text written in the first century in Alexandria, Wisdom (Sophia) is characterized as the “spouse of the Lord,” the mirror of God’s energy and emanation of God’s glory, a concept similar to the Jewish articulation of the Shekinah, the feminine manifestation or presence of the glory of God. The philosophers, literally the “lovers of Sophia,” lamented that the virtues of Wisdom (often synonymous with the Holy Spirit) were so universally spurned. In the Wisdom books of the Hebrew Bible, the Sophia hawked her wares in the streets, but few were interested. She had fallen into ill repute, her precepts widely scorned—so, too, her human daughters were devalued and abused, as in the story of Eve and her alleged disobedience in the Garden of Eden that stigmatized her daughters. As in the Genesis story, the fate of Wisdom/Sophia was the story not of one woman, but rather of all women, seen as inferior to men from birth. In Magdalene, they witnessed the redemption and return of Sophia as the cherished partner and beloved of God.

Recognizing that the gnostics were initiated into Pythagorean geometry and its sacred canons, we can see how this geometric figure connects the story of the fallen Sophia—the soul—with Mary Magdalene. Using the standard Greek ratio 22/7 for pi, the outer circumference of a circle with a radius of 7 is 44, closely associated with 444, the sacred number by gematria of the phrase σαρξ και αιμα (flesh and blood), found in 1 Corinthians 15:50, and associated with matter and the created earth in the Greek canon of sacred number. The area of the same circle representing the Sophia in her descent into the flesh is calculated by multiplying radius squared by pi: 49 × 22/7 = 154, synonymous (by virtue of the colel of +1 or –1) with 153, the sacred number of h Magdalhnh, Mary’s epithet. A further association of Mary Magdalene with a circle is found in her official feast day on the Roman Catholic calendar of saints, the twenty-second day of the seventh month.

The myth of the fallen Sophia was apparently widely promulgated among gnostics and was integral to the story of Mary Magdalene interpreted from the gospel narratives. Gnostic Christians saw the Sophia myth as a metaphor for the soul in each person that, instead of being conscious of its divine origin and true nature centered in the spiritual core, the “bridal chamber” of its being, had somehow fallen away and mistakenly identified itself with its flesh and senses.13 Having forgotten the divine spark for which it is a vessel or temple, the individual eagerly sought gratification of fleshly desires in excessive self-indulgence, often falling into gross temptations, lusting after the “fleshpots of Egypt,” and sinking farther and farther from its spiritual center. The sinful and ignorant person becomes corrupt and spiritually lost, like the prodigal son in the gospel parable.

The myth continues. The soul wanders in exile, succumbing to temptations of the flesh and ultimately becoming disillusioned with her sordid and destructive lifestyle. She begins to feel the alienation from her source—her true spiritual nature—and finally repents her willfulness. In a moment of desperation, she cries out to God for salvation and immediately her bridegroom/brother—the Christ—is sent to rescue her and bring her back to her true self. They unite in the bridal chamber—re-creating the archetypal hieros gamos, or sacred union of Sophia/Logos. This is the story of every soul and its journey toward transformation and reunion—a theme that recurs in several gnostic texts, including the Pistis Sophia and the Hymn of the Pearl. It is metaphorically extended to Mary Magdalene as well.

We can see how, for these gnostic communities, the Magdalene in the canonical gospels embodied the fallen Sophia and how her redemption from Luke’s sinful woman to favorite disciple modeled the soul’s journey from alienation to union with Christ. Luke’s allegation that Mary Magdalene was cured of possession by seven demons is an allusion to her spiritual purification and strongly influenced articulaton of the myth that she was redeemed from a life of prostitution. Over the centuries, this became the prevailing story of Mary Magdalene even for orthodox Christians. She was styled the penitent Sophia redeemed and enjoying intimate spiritual union with the risen Christ.

Magdalene’s Spiritual Preeminence

In the Pistis Sophia, probably written in the third century, Mary Magdalene engages in most of the dialogue with Jesus and, by the insightful nature of her questions, establishes that she is the most enlightened of the disciples, earning Jesus’ praise for her understanding of his spiritual teachings. “Jesus, the compassionate, answered and said to Mariam, ‘Mariam, thou blessed one, whom I will complete in all the mysteries of the height, speak openly, thou art she whose heart is more directed to the Kingdom of Heaven than all thy brothers.’ ”14 In contrast, the mother of Jesus, who is also present in this text, is called the other Mary and has markedly lower status than the Magdalene. For modern Christians, this seems an intolerable affront to the Virgin Mary, demoting the woman we have been taught to hold in highest esteem as the Blessed Mother and even Queen of Heaven. It shocks us to find her demoted to the “other Mary.” Where could the gnostic author of the Pistis Sophia have gotten this idea, so at odds with our view of the honored status of the Blessed Virgin Mary?

The gnostic tradition of the preeminence of Mary Magdalene at the tomb on Easter morning actually stems from the canonical gospel of Matthew, which places two women at the sepulcher of Jesus on the evening of his entombment and again on Easter morning: “But Mary Magdalene and the other Mary were there, sitting opposite the sepulcher” (Matthew 27:61); “ . . . as the first day of the week began to dawn, Mary Magdalene and the other Mary came to see the sepulcher” (Matthew 28:1). This other Mary, the mother of James and Joseph, is sometimes claimed to be Jesus’ aunt, the sister of his mother, by Roman Catholic theologians zealous to uphold the tenet of the perpetual virginity of the mother of Jesus. But, as we noted earlier, in reading Mark 6:3 and Matthew 13:55, we conclude that she is the mother of Jesus—and also of James, Joseph, Simon, and Jude, who are clearly identified not as the cousins, but as the brothers of Jesus. The Greek language has a word for “kinsman” that could have been used in this passage, but was not. If Mark, and later Matthew, had wanted to identify these four men as cousins of Jesus, they could have used the word for “cousin” (νεψιοσ) rather than “brother” (δελφος).

Only once, at the foot of the cross in the fourth gospel, is the mother of Jesus mentioned before Mary Magdalene in the gospels. Later Christian theologians elevated the Virgin to preeminence as the Theotokos (Godbearer) and Mediatrix—an attribute of the Great Mother. But in the texts of the suppressed gnostic communities, Mary Magdalene is invariably recognized as the spiritual partner of Jesus, his intimate companion—the koin nos whom he loved more than any other woman and more than all his other disciples. This view is irrefutably supported by twin pillars of evidence from the canonical gospels: the mythology of the sacrificed king at the heart of the Christian story; and the gematria of h Magdalhnh, the title of Mary Magdalene. Her sacred number, 153—calculated by adding the letters of her title—equates her symbolically with the 153 fishes in the unbroken net in John 21:11, a metaphor for the Church in the geometry story presented in that

chapter.15 It associates her also with the vesica piscis, the vessel of the fish—an archetypal symbol of the Great Goddess known

to Greek geometers as “womb,” and “doorway to

life.”16 The vesica piscis bears further feminine associations with the bridal chamber and the Holy of Holies.

nos whom he loved more than any other woman and more than all his other disciples. This view is irrefutably supported by twin pillars of evidence from the canonical gospels: the mythology of the sacrificed king at the heart of the Christian story; and the gematria of h Magdalhnh, the title of Mary Magdalene. Her sacred number, 153—calculated by adding the letters of her title—equates her symbolically with the 153 fishes in the unbroken net in John 21:11, a metaphor for the Church in the geometry story presented in that

chapter.15 It associates her also with the vesica piscis, the vessel of the fish—an archetypal symbol of the Great Goddess known

to Greek geometers as “womb,” and “doorway to

life.”16 The vesica piscis bears further feminine associations with the bridal chamber and the Holy of Holies.

By insisting on the role of Magdalene as the one most intimately associated with Jesus and his teachings, the gnostics were deliberately upholding the experiential, mystic way of personal encounter with the Divine. In the Apocalypse of Peter, another text from the Nag Hammadi library, some orthodox Christians who called themselves bishop or deacon are characterized as waterless canals. Apparently their gnostic adversaries sensed that the legalistic literalism of the orthodox flowed from an empty well.

Several gnostic texts, especially the Gospel of Mary, bear clear witness to the high esteem in which these suppressed Christian sects held Mary Magdalene and the Way of personal enlightenment for which she was their spokeswoman. On the basis of these long-suppressed documents, feminist Bible scholars eagerly support the supreme status of Mary Magdalene among the apostles of Jesus. Not only is she the messenger first commissioned to carry the good news of the risen Lord, as established in the canonical gospels, but according to texts from the gnostic library, she also endeavors to sustain and comfort the other apostles, confiding to them the secret teachings she has continued to receive in post-resurrection visions of Jesus. In the Gospel of Mary (written c. 120–150), her emotional revelations are received guardedly and with a marked lack of enthusiasm by several apostles, especially Peter, whose resentment mirrors the tension between Church fathers and gnostics whose gnosis, or knowledge, of the Divine came through experiential, direct illumination.

Concretizing the Word of God

This tension continues. Today, as in the past, Christian clergy are notably reluctant to accept ecstatic dreams, visions, and channeled messages received by members of their flock, believing that such transmissions are unreliable at best and at worst misleading and heretical. They prefer to confine the communications of the Divine to the word of God already expressed in the Bible. For them, the prophet does not go to the mountain to hear the word of God, but rather, the prophet went to the mountain, and the revelation received is a sealed book. Do they not muzzle God?

What began as a movement springing from the life, ministry, and teachings of the Jewish rabbi Yeshua, the Nazorean, celebrated in small gatherings around a Eucharistic meal of bread and fish, became a centralized liturgical religion promulgated by a hierarchy of exclusively male—often celibate—priests. At the same time, in the late second century and thereafter, the voice of his beloved, symbolic of his community, was silenced, a condition solidified by the orthodox when the First Epistle of Timothy was accepted as an authentic teaching of Saint Paul: “I do not allow women to teach or to have authority over men.” Based on linguistic studies comparing 1 Timothy with letters confirmed as written by Paul, modern scholars recognize that this letter to Timothy cannot be attributed to Paul. But that determination comes sixteen hundred years too late to restore the voices of women to Western civilization—women who, like the bride herself, had been forced into figurative exile. By the fourth century, the voices of female leaders of the Church, whose early ministry was modeled on that of Mary Magdalene—and on the sister-wives of apostles and brothers of Jesus traveling as missionary partners in his entourage—were largely silenced and are only now being recovered.

Many contemporary Christians argue that restoring women to leadership roles in their communities would redress the imbalance inherent in Christianity by reestablishing the powerful model of gender equality and shared authority indigenous to the original Christian experience. Irrefutable historical justification exists for this movement. Already in recent decades, some mainstream churches have welcomed women into ministry where they share decision making with male priests and pastors, although several of the more conservative Christian denominations refuse to consider such a radical move, believing it to be unprecedented and nonscriptural. These denominations cling to the model of the twelve male apostles as the leaders exclusively designated by Christ to guide his Church. Yet, as we have discussed, clear scriptural evidence points to both male and female disciples following Jesus and to early Christian evangelists who traveled and gave witness to the good news as missionary couples. And always, Mary Magdalene—not a male apostle—was reported to be the first witness to the resurrection.

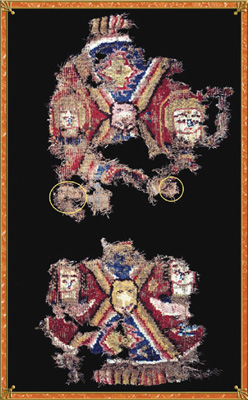

PLATE 11: “Exile Carpet” fragments (c. A.D. 150–180). Photograph Courtesy of Jeremy Pine.

PLATE 13: Segna di Buonaventure (c. 1298–c. 1331), Saint Magdalen. Alte Pinakothek, Munich.