The Beloved Espoused

And I saw the holy city, New Jerusalem, arrayed as a bride adorned for her husband.

REVELATION 21:2

In his Answer to Job, the mystic psychologist-philosopher Carl Jung makes a comment that sums up the need to restore the human bride of the human Jesus to our collective experience. In discussing the archetypal bridegroom of Christianity and his bride, Jung writes that the “equality” of the couple “requires to be metaphysically anchored in the figure of a ‘divine’ woman, the Bride of Christ.”1 Jung insists further that just as the human, physical bridegroom Christ cannot be replaced by an institution, the bride needs to be a personal representation in a human form. We cannot envision a human Jesus embracing a building—church or city—full of people; the image must be rejected as incongruous. If we are to envision a historical Jesus embracing a bride, she cannot be a mere metaphor. What we can envision is Jesus embracing a woman—his Domina counterpart—who represents her people, the ekklesia. In the Apocalypse, the bride descends from heaven to celebrate her nuptials (Revelation 21:2). She is the human embodiment of the Holy City, the New Jerusalem. And the goal of Christian theology is her sacred marriage with the eternal bridegroom.

The gospels of the New Testament provide us with a woman perceived to represent the community in its perpetual expectancy and hope for fulfillment of the millennial prophecies, when God will dwell in their midst. The only consistent candidate for this role of bride is Mary, the sister of Lazarus, called the Magdalene. Any possible confusion about the identity of Mary Magdalene was set to rest when Pope Gregory I proclaimed in a sermon delivered in 591 that Mary Magdalene was the sinful woman who anointed Jesus; John’s gospel names her Mary, the sister of Lazarus. In all probability, the pope was not making a controversial statement; he was articulating a belief already widely held in Western Europe, where churches built in honor of Mary Magdalene were frequent and her historical presence celebrated. She was one of the most popular of all Christian saints and her image the one most often painted by medieval artists, with one exception only—that of the Virgin and Child, an image illustrating the prevailing doctrine of the Theotokos honored in the East.

Mistaken Identities

In Western European art, Mary Magdalene’s image became inextricably compounded with two other female saints popular in medieval times—Saint Mary of Egypt and Saint Barbara—the former, by virtue of her legend, and the latter, by association with her iconography. Each of these probably fictional saints offers valuable insight into the medieval faces of Mary Magdalene.

Saint Mary of Egypt, or Mary Gyp, as she was affectionately known, was a prostitute whose story was brought back from the Middle East in the twelfth century by returning Crusaders. The soldiers apparently found in her a sympathetic patroness who looked with leniency on sexual indiscretions. Her legend asserts that Mary of Egypt was a third-century prostitute who obtained passage to Palestine by offering to ply her profession on board the ship. Upon arrival in the Holy Land, she converted to Christianity and gave up promiscuity, living out the rest of her life as a desert hermit. Her story, like that of Mary Magdalene, is found in the thirteenth-century Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine. One of the miracles associated with the dark Mary the Egyptian was ascension of her body into heaven, a favor extended to the Virgin Mary but also to Mary Magdalene by artists who confused her story with that of the Egyptian prostitute. Both Marys are said to have been harlots, both repented and were converted to Christ, both became hermits for the final decades of their lives. A further confusion in their stories is the child/servant Sarah, also called “the Egyptian,” said to have been among the party of Christian exiles who traveled to Gaul with Mary Magdalene. Apparently, some features from tales of the Egyptian prostitute, blackened by the relentless desert sun during her years in isolation and stripped naked as her clothes gradually disintegrated, were projected onto Mary Magdalene by medieval devotees. We could speculate that the emaciated Mary Magdalene effigy of Donatello (1389–1466) might have been inspired as easily by the story of Mary the Egyptian as by that of Mary Magdalene, who, it is said, lived for thirty years on the Eucharist wafers brought daily to her mountain cave by angels, one of the colorful details found in the account of her life published in the Golden Legend.

In 2002, I spent part of an afternoon in the Chapel of the Most Holy Trinity at West Point, New York—the chapel in which I was baptized as an infant and in which the Emmanuel prayer community was formed in 1973. I decided to examine images of Mary Magdalene in the chapel that was my spiritual home for so many years of my life. At first I was dismayed. Looking carefully at each stained-glass window, noting its scriptural or historic reference, no image of Mary Magdalene appeared present in any of the scenes. Just as I was leaving, disappointed, I glanced over my right shoulder at the stained-glass window behind me and felt prickles down my neck. There she was after all, standing regal in a magnificent mosaic of colored shards, gleaming in the spring sunshine.

As I looked more closely at her image, I recognized that Mary Magdalene was suffering once again from a case of mistaken identity. Standing in her sunlit window, she held a tower in her arms. A chalice was depicted below the image, while the inscription identified the woman as Saint Barbara. But the tower and chalice are associated with Mary, whose title is derived from the Aramaic word for “tower” and whose legend claims that she brought the Holy Grail to Europe. Often Saint Barbara wears the symbols of martyrdom in medieval iconography, but a crown is also a universally accepted symbol for royalty. In fact, a crown with numerous points originally represented the turrets and ramparts of a walled city, symbolically placed on the head of its patroness or protector. A famous early example of this artistic representation is the relief carving of the Great Goddess dating from the Roman period. She wears a replica of the city of Aix on her head—the prototypical crown.

In 1969, when the Roman Catholic Church revised its official calendar of saints’ feasts, Saint Barbara was summarily dropped, her story deemed spurious. Sealed in a tower, the third-century Barbara had been so eager to become a Christian—or so the story claimed—that she let down her hair so that a priest could climb up to bring her the gospel and the Eucharist, a story strongly reminiscent of the heroine in the European fairy tale Rapunzel. Barbara’s father, an important Syrian official, was so angry at Barbara’s profession of Christianity that he ordered his own beautiful daughter beheaded. On his way home from the execution, he was struck by a bolt of lightning and killed. Combining various elements of this legend, Barbara became the patron saint of military engineers and artillerymen, miners, masons, and firefighters, protecting them from sudden death by fire or explosion. The name Barbara means “foreign woman.” Her bizarre legend first circulated in Europe during the seventh century, contemporaneous with Merovingian rule in the northern regions of France. It gained popularity in the ninth and tenth centuries, when legends of the Holy Grail emerged in the oral tradition, though not yet written, and continued throughout the Middle Ages.

But, as in many medieval stories about the saints, details of Saint Barbara’s legend seem contrived, though they may hold a fossil of truth, as so many legends do. I think it probable that an artisan or artist created an image of a Mary Magdalene with her traditional long hair, a tower (derived from the root word of her honorific—magdala), a Grail chalice, and a royal crown. People unfamiliar with Hebrew might not have recognized the image as a rendering of Mary Magdalene, Grail bearer and ekklesia, so the iconography could easily have been misunderstood, and perhaps years later someone generated a legend to match the icon—ex post facto naming the woman Barbara and creating the bizarre story, now rejected by the Church, to explain the long hair, the tower, the chalice, and the crown. As the now revised story was told and retold and the icon copied in various forms, shapes, and sizes, the legend of Saint Barbara proliferated, veiling the original connection with Mary Magdalene. I am convinced that Saint Barbara was a cover story invented to protect Mary Magdalene and her connection with the Grail and its heresy. We are lifting its veil.

Another anomaly remains associated with the icon of the Grail and the long hair associated with Mary Magdalene. Christian paintings, but also statues standing along the outer walls of Gothic cathedrals at Chartres, Freibourg, and other European cities, often present a figure who symbolizes Christianity. She wears a crown and carries a chalice, and she may hold a banner emblazoned with a cross. In paintings, the cross is red on a white background. The figure personifies the Church, the bride of Christ. The crown proclaims her as royal bride and the chalice she holds is supposed to be symbolic of the Eucharistic meal. The Christian icon appears related to Barbara/Magdalene iconography, remembering that it was Magdalene who represented ekklesia, beloved bride of Christ, among earliest Christian exegetes.

The painting Saint Magdalen (plate 13) by Segna di Buonaventure (d. 1331) shows her holding what looks like a tower rather than her traditional alabaster jar. She provides what I consider a missing link between Barbara and the Magdalene.2 She was also a barbara, a “foreign woman,” banished into exile in a faraway land. Her first exile was historical—the journey in a fragile boat across the Mediterranean Sea from her homeland. Her second was metaphorical—enforced exile from her rightful position throughout two millennia of Christianity. Because the feminine principle was no longer honored in the power-drunk cultural milieu of the Roman Empire, women were not honored, and because women were not honored, this woman was not honored. The historic reality mirrors the pattern established and enthroned in the Roman solar- or masculine-oriented value system.

Often artists do not supply titles for their paintings, leaving it to viewers to identify a scene or character by means of associated icons. We can see an example of a misidentification in the fifteenth-century painting from the Flemish school depicting a woman identified as Saint Barbara (plate 14). Painted by Robert Campin, the saint bears a strong resemblance to the image of Mary Magdalene in a painting by the artist’s contemporary Rogier van der Weyden (plate 15). The women in these works are depicted in nearly identical poses: Each is seated, reading a book, symbolic of Sophia/Wisdom in iconography; each is wearing a dark green gown, symbolic of fertility, over a gold brocade underskirt, the raiment of the bride. Robert Campin’s Saint Barbara has the long wavy hair often associated with Mary Magdalene, while the hair of Rogier van der Weyden’s Magdalene is hidden under her coif. The alabaster jar universally associated with Mary Magdalene is seen in the foreground of Rogier van der Weyden’s work, whereas the flask of ointment in the Campin painting is standing on a shelf to the right above the fireplace. A lily in a vase near the woman in Campin’s work is the symbol of the bride in the Song of Songs, where the bridegroom proclaims, “As a lily among thorns, so is my beloved among women” (Song of Songs 2:2). Art critics over the centuries hold that the lily is a symbol for the Virgin Mary and her perpetual purity, but the bridegroom in the Canticle speaks of it as a simile for his beloved, not his mother.

I believe that in Robert Campin’s painting, the woman with curly auburn hair is Mary Magdalene rather than Saint Barbara. The tower seen through the window belongs to the iconography of both women, but only the Magdalene is associated with the flask of ointment. The Xs in the upper portion of the window are vaguely suspicious; X is the common symbol of the alternative, underground version of Christianity that acknowledged Mary Magdalene as the dompna (lady) of their Domine—Christ himself. We noted similar Xs in the transom of the window in Tintoretto’s Christ in the House of Martha and Mary (see plate 12).

The enforced separation of the beloveds in Christian mythology amounts to the “great divorce,” which is thrice tragic when we realize that it was perpetrated for millennia by the preeminent and most powerful institution in Western civilization. The Roman Catholic Church abhors divorce, quoting and upholding gospel passages Mark 10:2–9 and Matthew 19:3–9, in which Jesus insists on the absolute sanctity of monogamous marriage. The ongoing ramifications of this enforced separation of the archetypal Christ couple to our culture are enormous—ultimately the domain of the wounded king denied his feminine partner becomes a wasteland, its towns in ruins, its citizens in misery. There is no justice, no peace, no hope in a domain where the leaders—the anointed and ordained shepherds—busily shepherd themselves instead of the sheep (Ezekiel 34:8).

At several periods during these two Christian millennia, the story of the beloveds at the heart of the gospel story was poised to break forth from the underground stream of mystics, artists, and intellectuals who were its perennial custodians. But each time the story surfaced, it was squelched, declared heretical, and again forced underground. When it surfaced among the twelfth- and thirteenth-century Cathars and their troubadours, it was brutally suppressed by the dungeon, fire, and sword of the Inquisition, formed in 1239 for that purpose, though Grail legends that sprang from the heresy gained popularity and were widely disseminated in medieval Europe.

Today, under attack by clergy and volunteer defenders of the faith who vehemently deny (or ignore) powerful circumstantial evidence supporting the sacred union, the story of the Christ couple is labeled fiction or bunk. What a pity that these modern-day heirs of the guardians of the walls who piously assaulted the bride of the Canticle, who beat her and stripped her of her mantle (a euphemism for rape in their culture), are still—even now!—bitterly determined to keep the bride from being reunited with her bridegroom. Jesus was separated from his beloved partner at the dawn of the new age of Pisces, when the gospels were yet new. How joyful will be their eventual reunion!

Perhaps the zealous guardians of today, eager to debunk the sacred marriage, should reread a story found in the Book of Acts. A respected teacher of the law, Gamaliel warned Jewish elders of the ruling council, the Sanhedrin, not to try to silence the apostles preaching the good news in the streets of Jerusalem: “[I]f this work is of men, it will be overcome, but if it is of God, you will not be able to overthrow it. Else you may find yourselves fighting even against God” (Acts 5:38).

Over the centuries, groups of enlightened and intuitive European artists and poets occasionally connected with the underground stream and the story of the forgotten bride. Artists from all over Western Europe used heretical symbols in their paintings, a fact that suggests they passed down the great secret of the fully human, married Christ from one generation to another, a subject discussed in greater depth in The Woman with the Alabaster Jar. In that book, I gave powerful evidence for the existence of the Grail heresy, concentrating on medieval and Renaissance artworks, artifacts, and folklore. I did not include an important but much later circle of artists and poets inspired by the Grail legends—the brotherhood of the Pre-Raphaelites, formed in the mid-nineteenth century by Dante Gabriel Rosetti and his close friends. This celebrated group is familiar to many as Victorian naturalist-romantics. Though not directly linked with the heretical Church of Amor, their paintings include lovely scenes from the Grail legends and various pieces with moral or tragic themes, often with ethereal women—goddesses of beauty and love from Arthurian legend and pagan myth.

Poetry created within this circle of gifted friends often focuses on religious topics, and some of the artists appear captivated by the legends and inspiration of Mary Magdalene. Several works of the Pre-Raphaelites depict Mary Magdalene, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Mary Magdalene (plate 16), a striking redhead robed in dark green, shown holding a large egg. His painting The Beloved (plate 17) depicts another ravishing redhead—the bride from the Song of Songs. Other paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites concentrate on the Grail legends and these (why are we not surprised?) contain a number of knights wearing capes and tunics emblazoned with red Xs—the primary symbol that identifies alternative Christian adherents of the Church of the Grail. Fossils of the secret tradition—the major arcana expressed in symbol in medieval watermarks and in tarot trumps of the earliest decks—survived and resurfaced in Victorian England among this visionary and inspired brotherhood of poet-painters. Many paintings of other Pre-Raphaelites, especially those of John William Waterhouse, focus on the feminine as archetype or goddess—surrounded by roses or lilies, with copious red hair and flowing garments—while their sonnets and other poems enhance this idealization of the beloved, often in a medieval context. Were these painters heretics or merely passionate devotees of the feminine as beloved?

Lady Greensleeves

A medieval Flemish master painted Mary Magdalene preaching the gospel, with people gathered around her in a woodsy setting (plate 18). Dressed in a brocade gown embroidered with vines, she shares her message of hope and regeneration. The boat in which she sailed to the shores of Gaul is visible in the distance. This painting touches on several themes connected with Mary Magdalene: There is no church in the picture; Magdalene cannot preach from a church pulpit, but only out in the open, as was the case for medieval “heretics” and reformers who met at night in secluded areas to share their faith. Artists from the Netherlands (the Low Countries) were particularly aware of clandestine practice of their faith because of the repressive measures of the Spanish Inquisition imposed upon them during the sixteenth-century rule of the Spanish monarchs Charles V and Philip II. Mary Magdalene represented those outside the Church in their struggle for intellectual and religious freedom. The vine motif of her gown is the ubiquitous reminder of the theme of regeneration associated with the feminine she embodies, the raiment of the messianic bride from Psalm 45. It also echoes the words of Jesus in John 15: “I am the vine, you are the branches” (15:5), and shows the continuity of Mary Magdalene with the fruitful message of the gospel she preaches.

While many medieval portrayals of Mary Magdalene show her dressed in crimson or gold brocade—sometimes both—a large number of artists, including Dante Rossetti and Agnolo Bronzino (see plate 24), chose to dress the lady in green, the color associated with fertility and renewal, as in the veriditas, or principle of “greening,” expressed in the poetry and other works of Hildegard von Bingen. Indeed, Mary Magdalene is often shown wearing maternity clothes and obviously pregnant. Her green gown apparently cloaks an advanced pregnancy in The Resurrection of Lazarus, by Geertgen tot Sint Jans (see plate 7); and in Mary Magdalene, the left panel of Rogier van der Weyden’s Braque family triptych Mary Magdalene (see plate 6), she is wearing a tunic that laces up the front. Given that medieval women did not own many gowns, this was a typical medieval maternity garment, easily adjusted to accommodate advancing stages of pregnancy. The gold brocade and red Xs so often associated with Mary Magdalene and her great secret are displayed on the sleeves of her blouse.

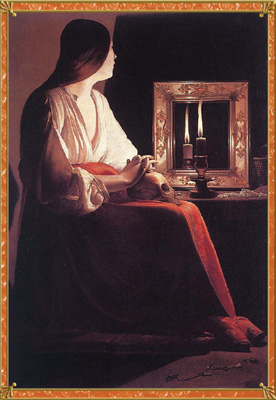

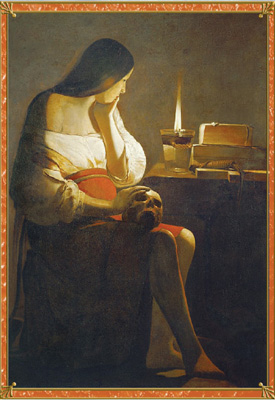

Several “penitent Magdalene” works by Georges de la Tour, painted between 1636 and 1644, also show a woman in advancing stages of pregnancy, culminating in The Penitent Magdalene (or Magdalene and the Two Flames—plate 19). Because the twin flames are an esoteric symbol for the beloveds as soul mates and partners, the meaning of the painting seems clear. Lying on the table near her is a large, irregular pearl of great price, a metaphor for the Kingdom of God. Like Magdalene herself, the pearl was hidden—so long and so deep—that no one realized it was gone or had any clue to search for it. One of the earlier de la Tour paintings of Mary Magdalene, Repenting Magdalene (or Magdalene of Night Light—plate 20), appears in the Disney movie The Little Mermaid, at the bottom of the ocean in the Little Mermaid’s treasure trove. It has been salvaged from a sunken galleon—“deep-sixed” like the Magdalene herself, her voice stolen when she was called prostitute. Another Magdalene painting, Piero della Francesca’s majestic fifteenth-century fresco in the Arezzo Cathedral, portrays a massive woman dressed in a green gown partially covered by a red and white cape. While green denotes fertility, red and white represent passion and purity, attributes that are not mutually exclusive—but are most desirable!—in a bride.

Very often Mary Magdalene appears to be associated with fertility and the promise of regeneration and renewal. As a fully human and full-bodied bearer of this archetypal principle, she fosters a deep connection with our flesh and blood, with our physical world, and with all creation, becoming the special patroness of those who would protect the environment and resources of the planet for future generations. While many of the Black Madonnas of France and Spain are dressed in gold, one notable exception is Notre Dame de la Confessione (Our Lady of the Witness) at Saint Victor’s Basilica in Marseilles, where she is dressed in an emerald green cloak and wears a brooch in the shape of a fleur-de-lis, symbol of French royalty.

PLATE 17: Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882), The Beloved. Tate Gallery, London. Courtesy of Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY.

PLATE 18: Netherlandish (active c. 1480–1520), Saint Mary Magdalene Preaching. John G. Johnson Collection, 1917, Philadephia Museum of Art, Philadelphia.

PLATE 19: Georges de la Tour (1593–1652), The Penitent Magdalene (or Magdalene and the Two Flames). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

PLATE 20: Georges de la Tour (1593–1652), Repenting Magdalene (or Magdalene of Night Light). Louvre, Paris. Courtesy of Scala/Art Resource, NY.

PLATE 21: Stephen Adam (d. 1910), stained-glass window, Kilmore Church, Dervaig, Isle of Mull, Scotland. Photograph courtesy of John Shuster.

PLATE 22: Jonathan Weber, Mary Magdalene. Copyright © 2004 by Jonathan Weber.

PLATE 23: Patricia K. Ballantine, Sacred Union. Courtesy of Patricia K. Ballantine, “The Creative Flame.”

PLATE 24: Agnolo di Cosimo Bronzino (1503–1572), Noli Me Tangere. Musée des Beaux-Arts, Besançon. Courtesy of Scala/Art Resource, NY.

Green is associated with fertility, and the () shape called the vesica piscis—Mary Magdalene’s geometric symbol—bears the same meaning: the womb of creativity, the matrix and doorway of life. The shape is replicated in leaves of numerous species of plants as well as in eggs and seeds: Almonds were sacred to the love goddess of the ancient world. A frequent artistic depiction of Christ shows the Savior enthroned within a mandorla, the vesica piscis often interpreted as a Christian symbol for the Holy Spirit or the Sophia, derived from its ancient associations with the goddess. This is a visual representation of Jesus’ anointing by Sophia/Holy Wisdom herself, manifested by his actual anointing by the bride bearing the alabaster jar in the gospels, in obvious contradiction to the previously cited claim made by Pope John Paul II that Jesus was never externally anointed.”3

Green is associated with hope, regeneration, and transformation, as well. A favorite medieval incarnation of the Lady of the Green as Mother Nature is found in Maid Marion, the companion of Robin Hood in the green wood of Merry Olde England. The popular folk hero and his bride provide yet another legend of sacred union and the “greening” principle that resonates within us. They mirror the King and Queen of the May, whose crowning culminated fertility rites that celebrated the vernal regeneration of the life force. Revelries in their honor included dancing around the phallic Maypole and making love in the woods and fields during festivals of Beltane, once celebrated on May first throughout Europe.

The verb to marry was derived from a nautical term meaning “to braid.” But its ancient etymology is also interesting: In Indo-European, a meri was a young wife and a meryo was a young man, whence in Sanskrit was derived maryo, a young man or suitor. The Latin verb maritare, meaning “to marry,” was the source of the Old French marier and Middle English marien. I find it enlightening that this word has her name on it—taken so for granted that we never pause to think of it. Neither is merry, meaning “joyful,” so very far removed from the bower of the beloveds.

The folk also retained the memory of the “ever green One”—the regenerative masculine principle—in their legends and festivals, equating that principle with Christ himself and incorporating it with the pagan custom of bringing in a fresh evergreen conifer or pine to celebrate the rebirth of the sun at the winter solstice. We call it a Christmas tree, but its triangular shape is the archetypal symbol for the primal One, the creative masculine energy of the cosmos. The “green man” who peeks out of foliage in various relief carvings in walls and pillars of medieval churches is a hidden aspect of that same concept of the “ever green” life force incarnate in Christ, whose full humanity was denied by the Roman Church, but who embodied the principle of regeneration and vitality in the eyes of the people—creation in all its diverse manifestations.

A poignant theme of regeneration and reunion is celebrated in the Hunt of the Unicorn series (early sixteenth century), displayed in the Cloisters in New York City. In this series of six panels, the unicorn is savagely hunted and destroyed, but in a seventh panel (probably not one of the original series), he is seen frolicking in the enclosed garden, a metaphor for the bride in the Song of Songs: “You are a garden enclosed, my sister, my bride, a garden enclosed, a fountain sealed” (Song of Songs 4:12). Flowers and herbs symbolic of love, marriage, and fertility surround the unicorn, and pomegranate juice drips from the tree above him, again reminiscent of the Song of Songs, where the beloveds tryst in the orchard of pomegranates.4 On the trunk of the pomegranate tree under which the unicorn rests two Xs are visible, formed by ropes attached to the initials A and E above his head. Double Xs were an important symbol for the alternative Christians who honored the sacred feminine, and occur often among their watermarks. Placed side-by-side and touching, the Xs form the rebus XX, the intertwined Λ and V symbols used to represent Ave Maria and Ave Millennium, two of their most significant slogans. The symbol of the compass and T-square, whose meaning is the quest for truth and enlightenment, was later adopted by the Brotherhood of Freemasons as its identifying logo.

The Nuptials of the Lamb

Although the movement itself was short-lived, lasting only about a decade, the style and influence of the Pre-Raphaelites spread well into the twentieth century. In 1906, on the Isle of Mull, situated off the west coast of Scotland, a church was erected to Saint Mary in the little town of Dervaig. The townspeople worked diligently to create their Kilmore (Church of Mary), designed to be the center of their worship. One of the beautiful stained-glass windows of the Kilmore is of special interest in our study of the many faces of Mary Magdalene (plate 21). The mosaic of brightly colored glass depicts the Christ couple celebrating their nuptials. They are “hand-fasted”—their right hands clasped—a widely recognized symbol for marriage still used in the marriage rite of some Christian denominations. The stained-glass window clearly portrays the nuptials of the Lamb and his bride, the Holy City, prophesied in the Book of Revelation. Behind the bridal couple standing in the doorway loom the twin towers, the medieval symbol representing the ramparts of Jerusalem.5

In the ancient rites of the sacred marriage, the bride represented and was identified with her land, her city and villages, her people. Often in the Hebrew Bible, as we have noted, the phrase “Daughter of Sion” refers to Jerusalem, the city, but also to the entire Jewish nation. In later doctrine, the title Daughter of Sion was one of those transferred to Mary, the mother of Jesus, but here in the window, the Holy City is identified as Jesus’ bride, not his mother.

Once again our attention is drawn to the line from the Song of Songs: “I am a wall and my breasts are towers” (Song of Songs 8:10). The bride in the ancient liturgical poem describes herself using the metaphor of the Holy City—its twin watchtowers and its wall. Perhaps we can understand better how the Twin Towers in New York City represented the land and the people of the realm, and yes, of the world—as the symbol representing the citadel, or City of God. The blow struck on September 11, 2001, was a blow against the civilization built on Judeo-Christian foundations and against the millennial vision of humanity as a single human family, the one bride and partner of God.

Fig. 7.1. Castles and towers are common watermarks found in paper manufactured in Europe between 1280 and 1600.

In the window of the Dervaig Kilmore showing Christ embracing his bride, Mary is robed in a green gown and is obviously pregnant, just as the ekklesia—the Church as bride—is always symbolically pregnant. She is the sacred container or vessel filled with God, always expectant, always fruitful. But the mystical marriage that is the goal of history need not exclude the historical union of the beloveds who modeled that union: As above, so below!

The full meaning of the Incarnation is that divinity dwells in humanity, consecrating it by uniting with it, incarnating in and with and through matter.

This elevates the flesh and blood of humanity to a status equivalent to the holy partner of God, not separate but one with the creator. The Christ couple provides us with a beautiful mandala and vision of that intimate union—allowing us to image the Divine as partners.

An inscription appears in the window under the image of the Sacred Bridegroom and his bride. It reads: “Mary has chosen that good part which shall not be taken away from her” (Luke 10:42). This quotation identifies the bride in the window as Mary of Bethany who sat at the feet of Jesus, absorbed in his teachings. But she is also the woman who performed the nuptial anointing of Jesus at the banquet (John 12:3), thereby proclaiming the kingship of the Davidic Messiah and at the same time prophesying his imminent death.

The artist who created the stained-glass window at the Saint Mary’s Church in Dervaig was a contemporary of Francis Thompson (1849–1907), whose remarkably prophetic poem “The Lily of the King” appears before the introduction to this book. Francis Thompson was a deeply religious Catholic who failed medical school and ended his life poverty-stricken and destitute due to opium addiction. He is most renowned for his celebrated poem The Hound of Heaven. In Lilium Regis, his vision of the Lily/Bride of Jesus being restored to her place of honor is deeply prophetic, for long has been the hour of her “unqueening.” The bride in the poem represents the people, the ekklesia abandoned and devalued, called “most sorrowful of daughters.” The promise is that her bridegroom will return for her: “His feet are coming to thee on the waters.” The Kilmore artisan apparently shared this vision of the bride restored and crowned, a theme perhaps ignited into consciousness by the Pre-Raphaelite movement a generation or two earlier. The Christ couple in the 1906 window wears medieval garb similar to that worn by figures portrayed in numerous neo-romantic Grail paintings by that brotherhood of artists, attesting to a continued fascination with the lore of the Middle Ages.

What does the stained-glass image depicting the nuptials of Christ and Mary Magdalene of Bethany actually prove? It does not prove that Jesus was married. Given that there is no wedding license for Jesus and his bride, documented proof of their marriage remains elusive according to literalists who wish to be called historians. But the picture in the window does prove that the artist who created the window, drawing from deep wells of Christian scripture and tradition, was inspired to believe in the sacred marriage of Christ with the sister of Martha and Lazarus, the bride whom nineteen hundred years of Christian tradition have called the Magdalene. The artisan chose to portray Jesus and Mary as hand-fasted, understanding Mary to be the woman who personified the Church assembly, the ekklesia, as the New Jerusalem. Prophecy found in the Book of Revelation provided him with a strong intuition that the ultimate purpose of Christian theology is the hieros gamos—the sacred union—or, perhaps better stated, the sacred reunion, of the Lamb and his bride, for do not be misled: The mandala at the heart of Christianity was—at its inception—the sacred partnership of the beloveds: “And I saw the Holy City, New Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, made ready as a bride adorned for her husband” (Revelation 21:2).

Who can this woman be, other than the Daughter of Sion who represents her land and people. Surely it is not the Mother of Jesus, but instead his wife who belongs with him in the bridal chamber of our hearts and in the eternal throne room in heaven. More and more I am convinced that the sacred marriage was the stone (the lapsit exillis) that the builders rejected, which must be set as the cornerstone if the true temple is ever to be erected on the soil of planet Earth, just as it must be honored at the core of the human psyche. The eternal partnership of flesh and divinity, of male and female, and of all the polarities—is summed up in the mandala of the archetypal bride and bridegroom. Like the elusive reign of God, it is already in our midst.

The Reign of God

Based on evidence coded into the gospels themselves, the revealed paradigm for the kingdom or “reign of God” was sacred partnership. The proof for this assertion is evident in the Greek gematria for the mustard seed that expresses the harmonious union of masculine and feminine energies.6

This argument from the Greek texts of the gospels is virtually ignored by the guardians of the status quo. One conservative Catholic priest told me several years ago that he could not consider gematria valid evidence of the sacred marriage because it is Jewish. He made this comment even after I explained to him that symbolic numbers are not encoded by gematria only in the Hebrew Bible but also throughout the Greek New Testament. Like the proverbial ostrich, this ordained minister was prejudiced against the evidence and refused even to examine it. Because no religious authority had suggested he consider gematria in the gospels, he closed his mind to the possibility that he was not fully informed. To construct my theory, I returned to the original Greek of Christian scripture documents to demonstrate the historical practice of this literary device by the authors of sacred texts of the Christian canon.7 The results are an astonishing testament to the union of the archetypal bride and bridegroom—styled as Lord and Lady of the Fishes.

The vital union of the opposite energies of the life force is a model for life on our planet, manifested in the intricate balance of all the workings of the universe—the cosmic dance. A significant parable attributed to Jesus bears testimony to this theme of sacred union at the core of the Christian message: “The reign of God is like a king who held a wedding banquet for his son” (Matthew 22:1). Many invited guests begged to be excused. This parable appears to be a midrash, or interpretation, of what actually transpired in the Roman province of Judaea in the first century: Jesus was inspired to teach and to celebrate a new model of radical gender equality and inclusiveness within his close circle of friends, lifting up the fallen feminine consciousness in the person of Mary Magdalene and embracing her fully, and at all levels. I envision them holding hands in her walled garden at Bethany on moonlit evenings in that last fatal springtime. But sadly, then as now, the guardians of the walls—entrenched in traditions of male dominance and patriarchal authority—were unable to hear his healing message of compassion and forgiveness, of justice and mercy, of gender equality and nonjudgmental inclusion. Apparently only the fringe or marginalized—prostitutes and tax collectors, simple peasants and day laborers, the blind, the lame, the halt, and mothers-in-law—were drawn to the inclusive promise of the reign of God revealed to be “already among us” and “in our midst.”

In the aftermath of the Crucifixion, the bride of Jesus was removed to a place of safety to await the fulfillment of time, the time prophesied in Micah 4:10 when she will be rescued and her former dominion restored. Citizens of the Roman Empire in the first century were unwilling or unable to embrace the revolutionary message of Jesus: Love your enemies and your neighbor as yourself, serve one another generously, forgive infinitely, love unconditionally. Over the next several generations, the voice of the bride was silenced and the original egalitarian message of Jesus was hijacked by patriarchal interests, later to become entrenched in the heir apparent of the Roman Empire—the Vatican and its Pontifex Maximus, a title once borne by the Roman emperor—with tragic repercussions for the planet that are sadly not over yet. What we sow, we reap. And what was sown in the second and third centuries of the first Christian millennium was a civilization organized on the Logos/hierarchical model—the pyramid—which has inherent at its core the principles of fire (pyr) and power, both words stemming from the same root associated with “father energy.” We should not be surprised that this model is exploding all around us—like bombs bursting in air!—because a civilization established on this model is out of balance. The attempt of Jesus to heal this separation was repudiated when the architects of Christianity rejected the cornerstone of his mission—the hieros gamos—and forced his beloved feminine counterpart into exile.

The vital question now is: Can we make this loss of the bride conscious—can we redeem the sacred feminine as partner—in time to save the planet we live on, our sacred vessel Earth, and the human family? Survival of the species Homo sapiens may depend upon the answer. It was not only her voice that was silenced when she was denigrated, devalued, and branded; it was our own!

What must we do to restore the voice of the bride?

Reclaiming the Sacred Union

The first step in restoring our Paradise Lost is to recognize that the mandala, or pattern of the Divine in holy partnership, is archetypal, manifested in ancient times as the sacred marriage of male and female—the interplay of cosmic forces in harmonious embrace. The harmonious interrelationship of the opposite energies was celebrated by our very earliest ancestors, who noted the eternal cycles of the seasons—the recurring cycles of life, death, and renewal. In their festivals, they celebrated the never-ending story of the return of the light at the winter solstice and the revitalization of the life force during the vernal equinox, in rites of hieros gamos, retained in the Easter mysteries named rather appropriately for the goddess Oester, whose name is derived from Ishtar, the consort of Tammuz. In recognizing this fundamental, archetypal paradigm for partnership, we affirm and embrace cosmic reality and experience at all levels.

But we must also acknowledge that religion is man-made and reflects our worldview and cosmology. In Pope John Paul II’s suggestion during his 1999 Easter homily that the God on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel was not really God—who is beyond all images—he was tacitly admitting that the image of God celebrated in Christian denominations worldwide is actually a false image of the Divine. Worship of an exclusively male image of God is idolatrous and has dangerous implications. It is dangerous not because it offends a passionate and jealous God, but because the masculine principle embodied in an exclusively masculine image of God becomes concretized on earth as a preference for males: for male children at birth and for male attitudes, wants, and desires. The trend of society is to become action-oriented, left-brained, and right-handed; everyone serves the power principle, everyone “rides the Beast.” The waters of the artistic-intuitive are dammed and the rivers of living water—inspiration and mysticism—run dry. The garden becomes a wasteland.

Pope John Paul II once stated frankly that the Roman Catholic Church is not a democracy. How could it be, when its fathers silenced the voice of the bride in the second and third centuries and continued to disenfranchise subsequent generations, styling adherents as children rather than cocreators? But always in tension with the institution’s hierarchy is the gospel itself, and the authentic, liberating teachings of Jesus Christ, in whom as Paul says “there is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for all are one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28). Democracy is modeled on the ancient symbol of hieros gamos, the  . In

this archetypal hexagram, the Δ, representing the hierarchical or masculine principle embodied in the three branches of elected government, is in intimate equilibrium with the

. In

this archetypal hexagram, the Δ, representing the hierarchical or masculine principle embodied in the three branches of elected government, is in intimate equilibrium with the  , representing the feminine—the will and voice of the people. A number of the founding fathers of the United States were, after all, Freemasons who had inherited enlightened traditions from the underground stream of European civilization.

, representing the feminine—the will and voice of the people. A number of the founding fathers of the United States were, after all, Freemasons who had inherited enlightened traditions from the underground stream of European civilization.

The Healing of the Nations

Often I am asked, “What is the bottom line?”—what is my conclusion after thirty years devoted to restoring the bride to Christian consciousness? My answer is this: If the historical Jewish itinerant rabbi Jesus wasn’t married, he should have been. Extensive evidence in the gospels themselves confirms his marriage on the literal/historical and physical plane because marriage was a fundamental obligation in Judaism, rarely waived without comment. His wife is clearly identified in the gospels—by virtue of her anointing of the messianic king at the banquet and their embrace at the garden tomb. But the answer to this question is far more important on the metaphysical plane: Imaging a celibate God is bound (in extremis) to create a dysfunctional family. In Christianity, the model for true partnership and equality has been too long denied, the bride stripped of her robes and exiled, her voice stolen, and in her place her mother-in-law elevated to a celestial throne at her son’s right hand. Numerous medieval paintings celebrating this doctrine of the Roman Church show Jesus crowning his mother while Mary Magdalene kneels at their feet, still clasping the archetypal symbol of the nuptial anointing—the alabaster jar. And our fairy tales—Snow White, Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, The Little Mermaid—show us the sinister face of the witch or stepmother who has stolen the birthright and exalted destiny of the true daughter/bride.

Apparently the ancient Greeks were already aware of the two hemispheres of the brain and their separate functions. The wasteland created by worship of a celibate male deity stripped of his feminine counterpart is an issue explored by medieval alchemists, whose principle of psychological integration is expressed in a series of woodcuts showing the masculine and feminine principles in proper relationship. In the sixteenth-century series Rosary of the Philosophers, the sacred union of the opposite principles is personified in a king and queen representing right and left hands, correlated to left-brain (Logos-reason) and right-brain (Eros-relatedness) interaction.

Fig. 7.2. From a famous series of twenty woodcuts first printed in the second volume of De Alchimia opuscula complura veterum philosophorum, Frankfurt 1550, that depicts the alchemical marriage of sol and luna.

The woodcut series culminates in the marriage of the two figures and their final merging into one androgynous person, explained by Carl Jung’s principle of the desired integration of Logos and Eros in each individual—the ultimate goal of enlightenment gleaned from life’s experiences. Seeking God within the covers of a book is futile. True wisdom is more than intellect, more than experience. It flows from the union and integration of both ways of knowing—logic and intuition.

What are the possible benefits of restoring Mary Magdalene to her former position of highest honor? As bearer of the goddess archetype, the personification of the feminine face of reality, she brings us great gifts of creativity and intuitive knowing through experience. She also brings us profound connections with the earth and with one another—the kinship of all that lives and of all creation. The divine feminine is inclusive and tolerant, accepting of a wide diversity. She encourages us to live authentically and to connect with our emotions—with passion and compassion, with sensitivity to the needs of others, with consideration of their desires, even with willingness to listen (that rarest of all gifts!) and to relate to others in a way that comes from the heart. In a society that is deeply dualistic, we are becoming aware that stereotypes are dangerous and destructive: Teaching our sons not to cry and discouraging our daughters from studying math are grievous restraints on the human psyche. Gradually, we are grasping the meaning of Carl Jung’s psychological research confirming that all of us are both male and female, “formed in the image of God,” and that each of us must make her own—hopefully informed—choices at the core of her being. Stereotyping by gender and indoctrinating by memorized catechism do not feed the soul.

Having sent Mary Magdalene, the archetypal bearer of the color red and its connections to the flesh and blood of the human condition, into the obscurity of exile, Christian fathers deliberately dissociated themselves from the earth and the flesh. But in keeping with the important principle that what is suppressed becomes destructive, Western society is ever more materialistic and dissociated from the true feminine—agape, or unconditional love—expressed in deep wellsprings of mysticism and compassionate relationship with others. These elements were originally at the spiritual core of the gospel.

In our times, a tremendous surge of interest in the feminine half of creation has grown, manifested in women’s studies programs in universities around the world, in welcoming women into government positions and into the clergy of some, though not all, Christian denominations. This impulse is evident, too, in renewed interest in spiritual paths of mysticism, service to others, and voluntary simplicity. But is there a growing willingness to listen? To be present to those who suffer? To console the grieving and to comfort the bereaved? To work for justice? These, too, are manifestations of the sacred feminine—the eros of God. The word magnanimous has at its root mag, “great lady” or “great mother.”

Gradually, over the last two generations, women’s voices have grown stronger, and in some regions of the world, they are now heard for the first time in recorded memory. Women’s grave concerns are considered seriously in the halls of power, not only in the Christian West, but also across the globe; protect our children, protect our earth. And the movement goes forward. In the last two decades, we have seen new democracies born in regions suppressed by brutal dictatorship for millennia. Also in recent decades, women seeking role models to whom they can look for guidance rediscovered the many faces of the Great Goddess of antiquity. She had many names: Isis, Demeter, Inanna, Athene, Kwan Yin, Kali—strange-sounding names to women whose native tongue was English.

Twenty-five years ago, I was saddened by the movement of many women away from Christian denominations into worship of foreign-sounding goddesses. I wondered how they could abandon their Christian roots, how they could wander so far from home. Instead of leaving the Church of our youth, my own group of close friends developed a deep devotion to the Virgin Mary and to her rosary, which we prayed often—even daily—to Our Lady. Several members of the Emmanuel community went on pilgrimages to her shrines at Fátima, Lourdes, and Medugorje. One day in prayer in my own living room, I received the revelation that changed my life in an instant—that the preeminent woman in the Christian gospels was Mary Magdalene, bearer of the archetype of the goddesses of love, fertility, compassion, and wisdom. Somehow her story had been distorted and her exalted position denied. It was time to restore her to consciousness—not as a mere disciple or apostle of the historical rabbi Jesus, but as his beloved counterpart and complement—his wife.

Taking seriously this momentous revelation, and believing it to be a precious gift for the Church and for the entire human family, I devoted my life to researching the textual record and traditions and to correcting teachings regarding Mary Magdalene, never dreaming that time was ripening for a wider revelation of the restored paradigm I was shown. Now the good news of sacred partnership, embodied in the intimate union of Jesus and Mary Magdalene, is spreading across the planet like spontaneous combustion. Who could have anticipated this eventuality? Apparently the “sacred union” at the heart of the Christian mythology resonates with people on a very deep level.

Faced with the extraordinary phenomenon of Mary Magdalene’s return, apologists for conservative Christianity are retrenching. Modern-day guardians of the walls, like the ones who attacked the bride in the Song of Songs and stripped her of her mantle, wish the bride would again disappear into oblivion. While clergy in some Christian denominations show a reluctant willingness to allow Mary Magdalene the role of an apostle—messenger of the resurrection—most are unwilling to consider the radical paradigm shift inherent in the sacred marriage. In defense of their inflexible position, some clergy claim that Jesus would have been too busy establishing his Church and preaching his message to bother with marriage—forgetting that marriage was a fundamental obligation of Jewish males. Others claim that the idea of sacred marriage is pagan, unwilling to admit it is the fundamental model for life on our planet—there is no other. Still others insist they are clinging to the tradition of Christianity that Jesus was both celibate and chaste—failing to understand that the hieros gamos was the original tradition of the earliest Christians and that the tradition to which they cling is a distortion of that original faith. Some Protestant denominations are apparently taking a second look at Roman Catholic doctrines of the Virgin Mary, showing a new willingness to give her special recognition as the Blessed Mother. Could this embrace of the Virgin Mary be an attempt to scuttle the far more radical suggestion that the favored Mary was the one called Magdalene and that, as the intimate companion and consort of Christ, it is she whom we need to embrace?

Might Jesus have been married? The answer is yes. Archbishop John Shelby Spong, the retired Episcopal archbishop of New Jersey, and Dr. William E. Phipps, a distinguished professor emeritus of religion and philosophy at David and Elkins College—both of whom have researched this subject in great depth—support the view that Jesus was very probably married. Nor are they alone. The evidence, although circumstantial, is powerful and undeniable. They and other clergy who have spoken on this issue, including Dr. Bart Ehrman, of the University of North Carolina, and Reverend Richard P. Mcbrien, of Notre Dame, have stated that they do not think acknowledging Jesus as married and a father would be in any way denigrating to him or harmful to Christian faith or doctrine. One of the basic tenets of the Church is that Jesus was fully human as well as divine, “like unto us in all things except sin.” Marriage and sex within marriage are not sins. They are sacraments—signs of God’s presence with us and of God’s creative activity.

I raised other issues in my previous books that still need to be addressed. To my knowledge, critics rushing eagerly to debunk The Da Vinci Code have yet to offer a credible, rational rebuttal of the Greek gematria of the Magdalene (153) that associates her with the Great Goddess of antiquity and with the 153 fishes in the net (John 21:11), an acknowledged metaphor for the Church.8 Some critics have snubbed the whole argument, dubbing it “numerology” and “New Age,” believing that by giving gematria a negative spin, they can bury it. Gematria is not numerology. It is not New Age. It is a literary device used by educated philosophers of the Pythagorean tradition—both Jew and Greek—to enhance the meaning of important phrases in their texts. Because the phrases that contain gematria occur in the original Greek of the gospels, the argument that rests on the symbolic numbers in the New Testament stands as the most powerful original testimony to the sacred union—even now virtually ignored by most Bible scholars, including the seventy-four involved in the Jesus Seminar, who were apparently aware that gematria existed but decided not to examine it, although they spent many months establishing which quotes from the gospels were actually spoken by Jesus.9 The symbolic numbers of the Greek canon have been embedded in the sacred texts of Christianity for two millennia. They are not going to go away. This might be the time to examine them to see what added insights they reveal about the original teachings of Jesus.10

The Whole Truth and Nothing But the Truth

In the aftermath of scandals involving Roman Catholic priests, people are now, for the first time in centuries, seriously asking, “What else did they forget to tell us?” Because the current crisis of confidence in the Catholic hierarchy is directly related to this hierarchy’s dissociation from the sacred feminine, the relationship of Jesus and Mary Magdalene is entirely relevant to the problem. Enforced clerical celibacy, after centuries of devaluing the feminine half of creation, was mandated in 1139 when an edict by Pope Innocent II forced married priests to abandon their wives and children. Martin Luther, a former Roman Catholic priest, and other leaders of the Protestant Reformation, who saw no scriptural evidence for a celibate priesthood, repudiated mandatory celibacy when they established their own communities of believers. Luther himself married a former nun and had six children.

The twin pillars of my research are established in the canonical New Testament: The similarities between the Passion narratives with pagan rites celebrating the sacrificed king are indigenous to the gospels, as are the phrases coded by Greek gematria attesting to the preeminence of Mary Magdalene and to her unique partnership with Jesus. Each of these arguments from my research rests squarely in the accepted canon of our Judeo-Christian heritage. They are historical. They are not foreign or alien. They are not New Age. Nor are they dependent in any way on the gnostic gospels found in the Egyptian desert, texts declared heretical by Irenaeus in the second century and later anathematized by Athanasius of Alexandria in 367, although these texts do support the case that Mary Magdalene was the favorite companion whom Jesus cherished more than any other. The arguments made in my books in support of the hieros gamos union of Jesus and Mary Magdalene are rooted in the gospels. They are not fiction. They cannot be explained away or debunked. These points need to be taken seriously; they are rooted in the very scripture texts that all Christians believe to be the revealed and unerring Word of God.

The sacred union is confirmed in the earliest stratum of Christian witness, in the behavior of those brothers of Jesus and other apostles who, relying on the testimony of Paul in his first epistle to the Corinthians, traveled as missionary couples with their sister-wives, spreading the good news of an egalitarian and inclusive reign of God modeled on the Song of Songs and the archetypal mandala for life itself. These earliest Christians acknowledged the kingdom already in our midst and spread out all around us, waiting for us to recognize, embrace, and celebrate the sacred union inherent in the mustard seed. Ultimately, that union is manifested in the partnership of Divinity and humanity, expressed in Paul’s epistle: “Do you not know that your body is a temple for the Holy Spirit” (1 Corinthians 3:16). The core of the gospel message was attitude adjustment. We are each containers of an immanent and indwelling God. This is not the God on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, but the infinite, invisible, and ineffable Emmanuel who is “with us”—incarnate not only in Christ, but in us as well. The ultimate extension of this truth is demonstrated in physics by wave and particle theory—the manifest and the unmanifested are one, warp and woof of the same fabulous tapestry: existence itself.

I think it is likely that Jesus recognized and fully understood that his message would not be accepted immediately. As in the bridegroom parable mentioned earlier, the guests who were invited to the wedding feast of the king’s son offered excuses and did not want to attend. The wedding feast implies the presence of the bride as well as the bridegroom. But the time of the reign of God was not yet. Jesus sowed the seeds of his kingdom, the mustard seed found in his parables and logia, and some seed fell on good ground. It strikes us as odd that Jesus chose the lowly mustard seed for his parable, because mustard is considered a noxious weed in the land where he preached it as a simile for the kingdom of heaven. It is scorned as of negligible value, yet its sum by gematria bears the symbolic sacred number of the marriage of masculine and feminine energies—1746.11

Bringing Water to the Wasteland

Eager to embrace the partnership paradigm, men and women from all over the globe are now opening their hearts and minds to Mary Magdalene, rereading her story and seeking her truth. Many who abandoned Christianity in tears a generation ago are returning, like the exiles in the sixth century B.C. returning from Babylon to the Holy City “bearing their sheaves.” There is new hope in their hearts; they sense change on the wind, the prophetic breath of the Spirit: “[I]n the cities . . . there shall yet be heard, the cry of joy, the cry of gladness, the voice of the bridegroom, the voice of the bride . . .” (Jeremiah 33:10–11).

Due to the miraculous Internet, connecting people all over the world in nanoseconds, I receive amazing e-mails supporting my work and affirming my research. Often I receive poetry or works of art created to honor and celebrate Mary Magdalene. One such work (plate 22) is Jonathan Weber’s (Williams, Oregon) painting of an irresistible vision of Mary Magdalene. Another (plate 23) is an archetypal image of the sacred union as conceived by Patricia Ballantine, of Phoenix. The painting by the California artist Joan Beth Clair, called Alive in Her (plate 9), is yet another gift inspired by the Magdalene.

And these are only a shadow of all that will be manifested in memory of her in generations to come. On the cusp of the New Age now dawning, we are preparing for another Passover. We are called out of the symbolic Egypt of our materialistic illusions and the selfish indulgence of our sensual appetites into the Promised Land of enlightenment, with its attendant gifts of reconciliation, inclusiveness, and partnership. We are called to embrace the Wisdom traditions of the ancestors—to incubate, to intuit, to dream, as suggested in Peter Kingsley’s acclaimed book, In the Dark Places of Wisdom. As we leave the old paradigm of masculine dominance and patriarchal hegemony, passing over into the Age to Come, we must obey the request of Jesus to follow the man carrying a pitcher of water (Mark 14:13). He is the water carrier Aquarius—the zodiac sign of the next two-thousand-year stage of the journey on which the human family has embarked.

As we cross the river that is the final boundary, we cherish the sign of the age we are leaving, which we carry now crystallized in our hearts—the zodiac sign of the fishes—not one fish only, but two. The avatars, Lord and Lady of the Fishes, are hand-fasted in our new consciousness as in the window of Saint Mary’s on the Isle of Mull (see plate 21). The final book of the Bible, the Apocalypse of John (Revelation), speaks of the river of the water of life flowing from the throne of God and the Lamb, nourishing the tree of life that bears twelve fruits and leaves for the healing of the nations (Revelation 22:2). When the Lamb is united with his bride, New Jerusalem, this river will flow through the Holy City and out into the desert. The trumpets are blowing. It is the end of the age and time for the nuptials of the Lamb.12 In accepting at last the two-thousand-year-old invitation to attend the wedding feast of the king’s son, we are now ready to welcome the bride as well, for inherent in our embrace of the bride is the healing of the nations:

For Sion’s sake I will not be silent

until her vindication shines forth like the dawn. . . .

No longer shall she be called “abandoned”

or her lands “desolate,”

but she shall be called “beloved,”

and her lands “espoused.”

ISAIAH 62:1, 4