GENERAL PERSHING WAS CONFIDENT the reports that Villa had been shot were accurate and was determined to keep up the pressure. His columns galloped on, fluid fingers moving parallel to each other, detouring frequently to search villages and ranches, hoping to catch the wily guerrilla leader before he disappeared forever. They passed looted haciendas, where the corpses of vaquero soldados filled the arroyos, and the few chickens and hogs that had not been butchered roamed the fields. The Americans searched house after house, proceeding ever more cautiously after having been directed to several homes that allegedly harbored Villistas only to find men suffering from smallpox.

Like Colonel Dodd and the men of the Seventh, the other columns also made arduous night marches, appearing in the dawn light on the outskirts of sleeping villages only to find their quarry had vanished or, even more frustrating, that they had deliberately been given false information. The commanders of the provisional columns were skilled counterinsurgency fighters and their bleary eyes wandered restlessly over the brush and rock looking for the telltale scuff and half-moons of horseshoes. But the Villistas had many advantages; this was their country, their people. They had been toughened by six years of privation and war and could go two to three days without food or water. The Mexicans doubled back on their tracks, made fake trails, planted rumors and false stories with the villagers. And the weather, particularly in the mountains, was still frigid.

Pershing and his small entourage followed the columns in their heavy automobiles. From Dublán, they motored south to El Valle, 170 miles south of Columbus; then to Namiquipa, 240 miles; on to San Geronimo, 265 miles; and then Bachíniva, 285 miles below the border. Pershing was “on the prowl” constantly, writes historian Clarence Clendenen. “Little mention is made in any official record of this habit, but letters and diaries of veterans of the expedition frequently speak of his sudden appearances, usually after dark, observing closely, questioning closely, and occasionally giving terse orders. People who ‘were on their toes’ and performing their duties to the best of their abilities had nothing to fear, but his tongue was a sharp goad to all others.”

Pershing traveled like a gypsy, washing up in a collapsible canvas bucket, using overturned cans for camp chairs, a box for a desk, and the headlight of the touring car for a lamp. He was lashed by the same cold winds, slept on the same hard ground, and ate without complaint his nightly repast of “slum”—a stew made from beef jerky, potatoes, and carrots.

With each passing day, George Patton’s admiration for Pershing grew. He was especially impressed by Pershing’s efforts to maintain a fastidious appearance. “No frost or snow prevented his daily shave so that by personal example he prevented the morale destroying growth of facial herbiage which hard campaigns so frequently produce.”

Pershing also found much to admire in the young lieutenant. Patton was enthusiastic and tackled his assignments without complaint. Knowing how much his young aide craved action, Pershing sent him on frequent missions to deliver messages to the columns in the field. Patton used the excursions to do a little military sleuthing of his own. While delivering dispatches of Dodd’s fight to other military commanders in Namiquipa, for example, he made a detour to a hacienda, where he found all the occupants drunk. He took into custody a man who was wearing shoes identical to those issued to the American soldiers. “On the way to town he told me he lived in Namiquipa and that his children had small pox. They did, so I let him go.”

To aid them in their hunt, Pershing sent for Apache scouts from the White Mountain Reservation in Arizona, who were known for their uncanny tracking abilities. “On a rock ledge that seems to show nothing they will find some little stone lying in a position they know is unnatural. That is enough to establish the new direction of the trail. They seemed to know unfalteringly which way a man will logically turn under certain conditions,” one supervisor said. The scouts had skin the color of “well-used saddles” and waist-length hair and went by the names of Chicken, Ska-lah-hah, Nonotolth, Loco Jim and Chow-big, Skitty Joe Pitt and B-25. Comfortable as they were outdoors, they also enjoyed their creature comforts and demanded moisturizer for their lips, sand goggles for their eyes, pistols, web belts, regulation uniforms, and watches, which they referred to as “time on wrist.”

One of Pershing’s biggest challenges was coordinating and directing the chase over hundreds of rugged, poorly mapped miles. Telegraph wires were frequently cut by Villa’s allies; telephones were scarce, and field radios had a range of about twenty-five miles. He often found himself unable to communicate with General Funston in San Antonio, or the jittery folks back at the War Department. More often than not, that suited him just fine but he needed to communicate with the soldiers in the field. Most messages between the columns and field headquarters were delivered by human messengers traveling alone and unprotected on horseback, or by the pilots of First Aero Squadron. But the Jennies were so poorly designed and ill suited for the mission that four weeks into the campaign, almost the entire fleet had been destroyed or permanently grounded. With their small, ninety-horsepower engines, the planes were unable to attain the altitude necessary to fly over the Sierra Madre. They were frequently sucked up into whirlwinds and dashed toward the trees in precarious downdrafts. The dry climate wreaked havoc on the wooden propellers, and the water in the radiators often became so hot that the motors would splutter and stop in midair. “All officer pilots on duty with Squadron during its active service in Mexico were constantly exposed to personal risk and physical suffering,” Benjamin Foulois would later write. He continued:

Due to the inadequate weight-carrying capacity of the airplanes, it was impossible to carry even sufficient food, water or clothing on many of the reconnaissance flights. During their flights the pilots were frequently caught in snow, rain, and hail storms which because of their inadequate clothing, invariably caused considerable suffering. In several instances, the pilots were compelled to make forced landings in desert and hostile country, 50 to 70 miles from the nearest troops. In every case, the airplanes were abandoned or destroyed and the pilots, after experiencing all possible suffering due to the lack of food and water, would finally work their way on foot, through alkali deserts and mountains, to friendly troops, usually arriving thoroughly exhausted as a result of these hardships.

The maiden voyage into Mexico was just the beginning of the squadron’s harrowing experiences. The very next day, March 20, Lieutenant Thomas Bowen was turning to make a landing when his machine was caught in a whirlwind, stalled, and went into a partial nosedive. Bowen managed to escape with a broken nose and numerous bruises, but the airplane was completely destroyed.

In early April, two airplanes flew from San Geronimo to Chihuahua City to deliver dispatches to Marion Letcher, the American consul. In one airplane was Lieutenant Herbert Dargue with Captain Foulois as observer. The second airplane was flown by Lieutenant Joseph Carberry with Captain Townsend Dodd as observer. By prearrangement, Dargue and Foulois, who were carrying the original dispatches, were to land on the south side of the city. Carberry and Dodd, who were carrying duplicate copies, were to land on the north side.

The two planes reached their prearranged locations without any trouble. Foulois got out to take the dispatches into town and instructed Dargue to fly to the north side of the city and join the other plane. “As I left the ground,” Dargue later told a correspondent for the Washington Post, “I saw a squad of Carrancista soldiers drop to their knees and fire at my plane.” Upon hearing the gunshots, Foulois raced back, began screaming at the soldiers to stop, and was promptly arrested. As he was marched to jail, followed by a surly mob, he saw a U.S. citizen and urged him to contact the American consul and tell him what had happened.

Dargue managed to fly to the north side of the city, where he met Carberry and his plane. (His partner, Captain Dodd, had already left to deliver his duplicates.) The two airplanes soon attracted another mob. “There was quite a crowd of natives and Carrancista soldiers standing around, and it was easy to see that they weren’t any too friendly. Carberry and I had both seen a larger field near an American factory (about six miles from the city), and we decided to fly over there, where we would have protection,” Dargue continued.

While the two pilots discussed their plans, the crowd drew closer. “The natives were crowding around the planes, cutting off pieces of fabric for souvenirs, burning holes in the plane with cigarettes, and tampering with the rigging. We inspected Carberry’s plane and found that they had taken the pins for the elevator and rudder, so we fixed them up with nails,” Dargue remembered.

Carberry cranked up his engine. With the mob shouting, he taxied down the field and rose into the air. Dargue took off next, the crowd pelting him with stones. He had only flown a short way when the top section of the fuselage blew off, requiring a forced landing. When he got out, he saw people jumping up and down on the aircraft part and chased them off.

At that moment, a photographer appeared to take a picture of the aviator and his plane. Playing for time, Dargue would move just as the photographer was about to snap the shutter, blurring the image. The photographer would then have to repose him and return to his camera. “For more than 30 minutes, he kept the photographer on the verge of hysterics and the crowd interested by moving just as the shutter was about to be snapped. He posed and reposed, and the crowd forgot its ire,” the Post reported. Finally a group of more sympathetic Carrancista soldiers arrived and dispersed the crowd. The airplanes were repaired and a few days later they returned to Pershing’s advance base.

Dargue soon found himself in trouble again. While reconnoitering roads near Chihuahua City with Robert Willis, he recalled, “We passed over a precipice and hit the most terrific air bump I have ever met. It was so severe that it bent the crankshaft and put the motor out of commission. I saw a little sandbed below and headed for it. There wasn’t enough room for a landing and I knew a crash was coming, but I had enough control to turn on a wing and light in a clump of trees which broke our fall.”

The two men were both knocked unconscious. Willis was the first to awaken. His feet were caught between the engine bed and gasoline tank and he had a deep gash in his head. “I thought he [Dargue] had probably thought me dead or gone off for help. After a time I heard him groan.”

After they had bandaged each other, they burned the plane and began walking in the direction of the nearest U.S. Army camp, which was sixty-five miles away. They tried to maintain a schedule of walking for an hour and then resting for ten minutes but soon grew delirious from thirst and hunger. “There was a little town ahead of us called Bustillos,” remembered Dargue, “and we were both watching it when we fell asleep. We slept for exactly an hour and then occurred the most peculiar experience I have ever had. We both awoke suddenly, both sitting upright and both staring toward Bustillos. There we saw four American Army automobiles, moving in our direction, as if they were searching for us. I knew both of us saw them, for we sat there for some time and discussed them, wondering how they had happened to become anxious about us when there was no check on our movements and no way of knowing where we were. Then, while we watched them, the cars slowly disappeared and the town was as empty as ever.” It was the first of many hallucinations they would suffer before finally reaching safety.

TO GENERAL PERSHING, the hostility that Foulois and his pilots encountered was just one more piece of evidence that proved the Carrancistas had no intention of helping him capture Villa. In fact, it seemed that troops of the de facto government were doing everything to obstruct his efforts. Similarly, the inhabitants in the villages and towns were also turning against the U.S. soldiers. As one captain put it, “The sentiment of the people in this section is growing stronger and more bitter against Americans on account of the presence of U.S. troops in Mexico.”

Occasionally, though, friendly residents visited his camp, mostly to sell food or gawk at the large horses and equipment. One evening, when spring had returned to the land, a wagon materialized in the blue dusk and began slowly rolling toward him. It was filled with musicians—a violinist, guitar player, cornetist, and bass viol player—dressed in rough cotton garb of peons. They were on their way home from a birthday party and wondered if the soldiers would like to hear some music. The men nodded enthusiastically and the visitors arranged themselves in a semicircle and began to play.

The musicians played Spanish love songs, full of yearning and pathos, and quick-tempoed tunes of bailes. This was the music that Pancho Villa had often danced to; even as his troops were laying siege to one city or another he would slip away to a dance, lumber around the floor in his great heavy field boots, and return at dawn to direct the military campaign. Glancing slyly at their hosts, the musicians ended their performance with “La Cucaracha,” the many-stanzaed song that celebrated Villa’s military victories and romantic exploits:

| La cucaracha, la cucarach | The cockroach, the cockroach |

| Ya no puede caminar | Can no longer walk |

| Porque no tiene, | Because it doesn’t have, |

| Porque le falta | Because it needs |

| Marijuana que fumar | Marijuana to smoke |

| Ya murió la cucaracha | The cockroach has already died |

| Ya la llevan a enterrar | They are taking it to be buried |

| Entre cuatro zopilotes | Between four buzzards |

| Y un ratón de sacristán | And a sacristy mouse, |

| Con las barbas de Carranza | With Carranza’s beard |

| Voy a hacer una toquilla | I’m going to make a scarf |

| Pa’ ponérsela al sombrero | And put it on the sombrero |

| De su padre Pancho Villa | Of your father Pancho Villa. |

| Una panadero fue a misa | A baker went to Mass |

| No encontrando que rezar. | Not resting there to pray |

| La pidio a la Virgen pura, | But to ask the pure Virgin |

| Marijuana pa’ fumar. | For marijuana to smoke. |

| Una cosa me da risa | One thing makes me laugh |

| Pancho Villa sin camisa | Pancho Villa without a shirt. |

| Ya se van los carrancistas | The Carrancistas have already gone |

| Porque vienen los villistas | Because the Villistas are coming |

| Para sarapes, Saltillo; | For serapes, Saltillo |

| Chihuahua para soldados | Chihuahua for soldiers |

| Para mujeres, Jalisco; | For women, Jalisco |

| Para amar, toditos lados. | For love, all the little ways. |

A hat was passed and the soldiers filled it with silver. Someone begged the musicians to play one last song: “La Paloma,” por favor. Shrugging their shoulders, they began. The melody was beautiful and filled with longing that matched the fading light and the mood of the homesick soldiers. Suddenly one of Pershing’s aides held up his hand. Confused and alarmed, the musicians stopped and the journalists looked uncomfortably at one another. The song, it seemed, had been a favorite of the general’s late wife. Everyone looked toward Pershing, who had moved farther away to study the mountains. For a moment, the peaks glowed with a red transparent light and the flat, pale rocks on the hillsides resembled fish scales. Then the color vanished and the mountains resumed their immutable shapes. Pershing returned to the campfire and asked the musicians to keep playing. So they finished the song, passed the hat once more, climbed back into the creaking wagon, and disappeared into the night.

DYSPEPTIC AND DISTRACTED, always distant from his men, Pershing was not a man who inspired affection. But respect he had plenty of, for he shared equally in the hardships, and although he was meticulous and reserved in his personal habits, he understood the needs of his soldiers and let them have their dice and poker games and even went so far as to establish a “sanitary village”—a sanctioned whorehouse—at the expedition’s field headquarters, which was guarded by the military police, and where both customers and local prostitutes were regularly inspected for venereal disease.

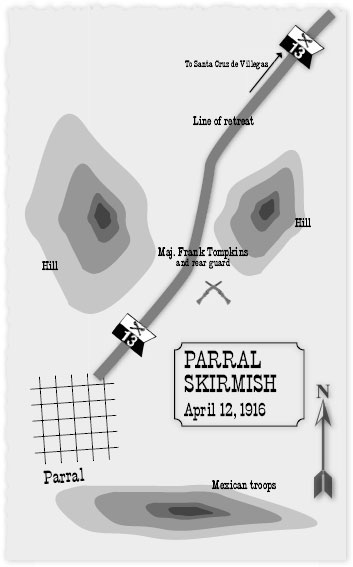

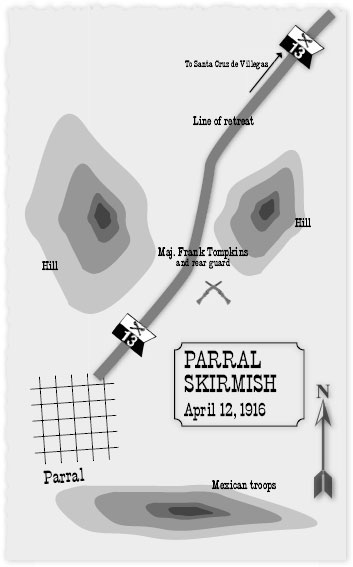

Such entertainment was not for him. Pershing kept his focus on one thing: the hunt for Pancho Villa. Suspecting that Villa might be heading toward Parral or the Durango state line, Pershing again sought to entrap him. Leaving Colonel Dodd and the horse soldiers of the Seventh to scour the mountainous country southwest of Guerrero, he sent three more columns south. The three roving squadrons formed a trident pointing toward Parral: Colonel William Brown and a squadron of Buffalo Soldiers from the Tenth would search the roads to the east; Major Frank Tompkins, who had chased the Villistas from Columbus, would drive down the middle; and Major Robert Howze, Eleventh Cavalry, would hunt the rugged trails to the west.

Within a day or two, Frank Tompkins and his provisional squadron of one hundred men had left the others behind. Tompkins was a distinguished-looking soldier, with thick hair going gray at the temples and an arrogant thrust to his chest. The son and grandson of West Point graduates, he had eschewed his own slot at the academy in order to enter the army early and speed up his advancement. He was a brave and energetic officer, but extremely contemptuous of all things Mexican. Now this pugnacious and opinionated man was the spearhead of the new advance.

Exultant at his new freedom, Tompkins ordered the horses into a trot, a gait that, paradoxically, was less tiring than a walk and allowed them to make about seven miles per hour. The rider at the front of the column used hand signals to indicate the pace: the right hand, raised briskly several times, was the signal to trot and the same hand held horizontally above the head meant slow down. The soldiers rode two abreast whenever the trail allowed and the horses eyed each other with a competitive playfulness. The countryside streaked by in muted tones of grays and greens. The horses that had managed to survive the first few weeks in Mexico had grown leaner and stronger and were now capable of marching for thirty to thirty-five miles a day on half rations. The nights were warmer, too, and both man and beast slept better and awoke less fatigued. Only the pack mules, which stood perhaps fourteen hands high and weighed eight hundred pounds, continued to lag behind. Their pace was somewhat understandable; they were often loaded down with machine guns and supplies that were equal to half their weight, and no amount of cajoling could make them go faster.

Tompkins breezed by the villages that Villa’s escort had skirted just a few days earlier—Cusihuíriachic, Cieneguita, and San Francisco de Borja—impoverished communities consisting of flat-roofed adobe homes and inhabited by burros, old men, women, children, and dogs, all hollowed out by hunger and revolution. Near San Borja, a group of Mexican soldiers rode out to meet Tompkins, bringing a note from their commander, José Cavazos, the Carrancista officer who had been aggressively searching for Villa. In polite language, Cavazos asked Tompkins to halt until he had talked with his superior. “I would esteem it very much if you would suspend your advance until you receive the order to which I refer.”

Tompkins rejected the request and rode on to the outskirts of San Borja, where he instructed one of his lieutenants, James Ord, who spoke Spanish fluently, to proceed into town and ask Cavazos to come out for a conference. While he was waiting, he ordered some of his men to dismount and take control of a nearby hill so that they would have the military advantage in the event Cavazos and his men “should think of indulging in any little act of treachery.”

After a while, the general and his entourage trotted out to meet him, the bright colors of the Mexican flag waving in the breeze. In comparison to the villagers, the Mexican troops were well armed and smartly clad, wearing khaki-colored uniforms, leggings or chaps, and gray felt sombreros with smallish peaks and tasseled horsehair bands. They carried six-shooters on their hips and thirty-thirty carbines in their saddle boots. Slung around the pommels were more belts of ammunition. Long, cruel-looking spurs hung from their boot heels and heavy, curved bits weighed down the mouths of the ponies—pintos, roans, sorrels, and bays.

Cavazos said he could not allow the U.S. troops to go through town. Besides, he said, Villa was dead, buried at Santa Ana, and his troops were just leaving to search for the body. (Cavazos was lying; by then he knew Villa was hiding at Ojitos and was on his way to search the area, but he wasn’t about to share his information with the gringos.) Tompkins reluctantly agreed to halt his journey south. As a show of friendship, Cavazos pulled out a quart of brandy, took a long drink, and handed it to Tompkins. “I took a good long pull and handed it to Ord who got his share and handed it to another of my officers who all helped to lower the line. When the bottle got back to Cavazos he took one look at it, made some exclamation in Spanish, which sounded like strong language, and threw the bottle in the bush.”

Tompkins and his men swung east toward the town of Santa Rosalía and then resumed their southward march toward Parral. They stopped at clear streams to water their horses and let their animals graze whenever possible on the tender new grass. At each place he camped, Tompkins would summon the leader—or “head man,” as he preferred to call him—from the nearest village and inform him that if the Americans were fired upon, Tompkins would promptly burn down his house. “These head men did not like this arrangement and put up the plea that they could not possibly know in advance of any such hostile intent toward my camp. I would only reply: ‘Then you are out of luck,’ and terminate the conference. I used this method when camping near any settlement and never had my camp disturbed. Other commands were not so fortunate.”

The cavalrymen had been given the usual rations of hardtack and bacon, a few potatoes, as well as some flour and salt, which they mixed with water and fried in grease to make “cowboy bread.” To supplement the fare, Tompkins ordered the local officials to bring them food. Although he always paid for the meals with Mexican silver, his arrogance and threats did not endear him to the inhabitants. One village official, who had been ordered to deliver a cauldron of hot beans to the camp, protested that the villagers had no beans and no pot to cook them in. “I told him we would have nice hot beans for breakfast or his house would burn. The beans came on time and were paid for in Mexican silver. There were enough for breakfast and luncheon, too.”

WHILE FRANK TOMPKINS and his troopers were eating their beans, Major Robert Howze and his squadron had succeeded in picking up Pancho Villa’s trail. Howze, a Texan, was in some ways the opposite of Major Tompkins. Unfailingly polite, he preferred to win allies through friendship and used intimidation only as a last resort. Like most of the other officers on the expedition, he was also a West Point graduate and greatly respected by his men. Accompanying him was a Mormon scout named Dave Brown, who spoke Spanish fluently, was also courteous in his dealings with the local inhabitants, and was almost as skilled as the Apaches when it came to tracking humans.

In San Borja, Howze and Brown conferred with the jefe político. Although the man was unwilling to share any information, Brown managed to get his wife to talk. Despite her husband’s hostile glares, she told the Americans that Villa’s troops had split up and Villa himself was going south. Howze’s troopers trotted out of town and soon found bloodstained bandages, cotton, and the remains of a campfire. The following day, they came across two more abandoned campsites and judged that they were moving four times as fast as Villa’s entourage.

As it turned out, Villa had been forced to leave his lair in Ojitos on April 6 after a sympathizer had rushed to warn him that General Cavazos was on his way. Still in great pain, he mounted his beautiful pinto and started south. On April 7, he stopped in the tiny settlement of Aguaje, ten miles directly south of Ojitos.

The following day, Howze arrived in a village that was just five miles to the northwest of Aguaje. Howze bivouacked in a deep canyon, and at daybreak, after being forced to shoot five horses, resumed his march. The American troopers passed within a mile of the village where Villa was staying and were now on a collision course with the rebel leader’s southerly moving escort. Then, the Americans came to a fork in the road. The left fork was covered with hoofprints, suggesting that a large contingent of mounted soldiers had taken it and were going east toward the village of San José del Sitio, which was nine miles away. A smaller group of shod horses had taken the right fork. Major Howze was inclined to take the left fork, in part because he was in desperate need of food and forage. But Dave Brown, the scout, suspected that the Villistas had deliberately driven a large herd of riderless horses up the left fork to throw the Americans off the trail and recommended that they take the right fork instead. After a long, agonizing discussion, the troopers decided to take the left fork. This enabled Villa, who undoubtedly knew exactly where the Americans were, to hurry down to Santa Cruz de Herrera, where he had been told that he would be safe while his leg healed.

The trip to San José del Sitio turned out to be fruitless for Howze and his men. The residents refused to sell the gringo soldiers food or forage. Desperate, Howze ordered the Mormon scout to round up and butcher some cattle anyway. As they were preparing to eat them, “a slender, mean-looking fellow” came into camp and demanded payment. They would later find out that the scowling visitor was a Villista, who undoubtedly had used the rustled cows as an excuse to scope out the troop strength and equipment of the gringos.

On the morning of April 10, Howze’s squadron left San José del Sitio. Knowing they were surrounded by spies, they marched east out of town and then reversed direction and cut back toward their old trail. Eventually they arrived on the ledge of a mountain. Spread out in the valley below them was the settlement of La Joya. Through their binoculars, the U.S. soldiers watched as several mounted men galloped into the town plaza, dismounted, and went inside the church. Soon they reemerged and began moving slowly away. A man mounted on a sorrel horse and wearing a large sombrero rode in the middle of the horsemen and appeared to be receiving a lot of attention. On the outskirts of the village, the Mexicans split up, with most of them, including the important-looking man, going south. A few headed in the other direction toward a canyon. Was this man Villa? Or a decoy? By the time Howze’s squadron had worked its way down the cliff, all the villagers had fled except for a Tarahumara Indian, dressed in white muslin, who had been circulating among the horsemen at the church. He was immediately taken into custody and questioned intently, but responded with a “perpetual smile.”

Howze dispatched soldiers to search the canyon. A young lieutenant took his rifle and hid in some bushes. When two mounted Mexicans appeared, he stepped out and demanded that they halt. Instead, they wheeled their horses and began galloping away. The lieutenant fired, dropping both men. One was wounded, the other killed. The villagers later identified the dead man as Captain Manuel Silvas, an officer who had participated in the Columbus attack. Back in La Joya, Howze’s troopers searched the homes and found several articles of clothing taken during the Columbus raid. As usual, the problem was trying to distinguish friend from foe; a Villista without a gun became just another Mexican. Howze’s men nevertheless tried to elicit what information they could before leaving town to follow the trail of the Mexicans who had gone south.

As they were meandering across a relatively flat piece of land, the troopers were caught in a vicious ambush. Two lieutenants galloped up the ridge where the enemy fire was coming from and eventually succeeded in dislodging the snipers. This time, the Villistas’ aim was more accurate: several troopers were wounded and a young private from Tennessee killed by a bullet through the head. His body was wrapped in a blanket and buried. The troopers, who had brought no shovels with them, used mess kits, forks, sticks, and even their bare hands to dig the grave. By the time they had finished, it was nearly ten o’clock at night and the squadron decided to rest for a couple of hours.

The ambush had obviously been staged by Villistas to slow down Major Howze’s progress. As the Americans bandaged the wounded and buried the dead, Villa reached Santa Cruz de Herrera and went to the home of Dolores Rodríguez, the father of a Villista general killed by the Carrancistas several months earlier.

Sometime after midnight, the cavalry troops arose and saddled their horses and marched sixteen miles south to Santa Cruz. They reached the village at 3:00 a.m. on April 11—only hours after Villa’s arrival. As the Americans approached the settlement, they were fired upon and returned the fire, killing two men. At daylight, they searched the houses and then rode a few miles out of town and camped. The command, “being more or less exhausted,” remained there for the rest of the day.

Afterward, one of Howze’s aides, Lieutenant Summer Williams, went into town to buy food and saw a group of Yaqui Indians, unarmed but wearing face paint, exiting from a ranch house a mile away. Knowing that some Yaquis had allied themselves with Villa, he became suspicious and returned to camp and urged Howze to attack the ranch house at once. “No one of us could get him to listen to the possibility of Villa and a small band being in hiding in this house. He prohibited any of us from going to this ranch house, and the following morning we marched south,” the frustrated lieutenant would later write. “I fully believe that this is where Major Howze and his column lost Villa and also lost our great opportunity.”

It’s not clear why Major Howze, who had been so dogged in his pursuit, stopped short of searching the house. But one thing was certain: both the men and the horses were on the edge of starvation. “Our animals were low in flesh, lame and foot sore; our men were nearly barefooted; the country was nearly devoid of food, and wherever we turned, we found less horse feed,” he would later write. Howze decided to head to Parral, fifty miles to the southeast. Though it was a two-and-a-half-day march away, he hoped to find there the supplies he so desperately needed.

BY APRIL 11, General Pershing and twenty members of the headquarters staff were camped in a cornfield on the outskirts of Satevó—four hundred miles south of Columbus, eighty-three miles north of Parral, and midway between his roving columns. The entourage, which consisted of four automobiles and three trucks, made a defensive square in the cornfield. Pershing ordered shallow trenches dug and inspected the small group, including the correspondents, to make sure their rifles and sidearms were in working order. The Times correspondent, Frank Elser, had lost his rifle.

“Soldiers don’t lose their rifles,” Pershing growled.

“No, sir, they don’t, soldiers,” responded Elser.

Pershing slept outside the square, on a dinky cot by himself. In the distance, he could see the flickering lights of the Carrancistas’ campfires. “The big moon, rising higher, touched everything with a luminous and breathtaking beauty. Sentries paced the hills. The coyotes yipped, a thousand of them,” wrote Elser.

Pershing could sense his troops were close to el jaguar now and wanted to be in on the kill. Driving toward Parral were Howze’s troopers, the swashbuckling Frank Tompkins, and Colonel William Brown, another magnificent officer in his sixties. A fourth detachment led by Lieutenant Colonel Henry Allen had been ordered to cut the weak men and animals from their squadron and concentrate on finding Pablo López.

On the way to Parral, Major Tompkins and his troopers had encountered an amiable Carrancista captain named Antonio Mesa who had offered to telephone ahead to arrange for a campsite and forage for the tired troopers. Given Parral’s history, it seemed highly unlikely that its inhabitants would look kindly upon the foreigners, but Captain Mesa assured Tompkins that they would be treated well. Urging their tired horses forward, the officers thought longingly of the amenities awaiting them. “We pictured the hot baths we should have, the long cool drinks, and the good food,” remembered Tompkins.

Sometime around noon on April 12, Tompkins reached the outskirts of the town. No representatives of the Carrancista government were on hand to meet him so the major left the main body of his troops outside the town and proceeded with a small group to the guardhouse, where he asked to be taken to the headquarters of the jefe de armas. When he arrived, he was introduced to General Ismael Lozano, who invited him upstairs for a private conference. Also present at the gathering was José de la Luz Herrera, Parral’s civilian mayor. The room had French windows overlooking the street and Tompkins could see his squadron down below, looking impressive and alert. The Mexican officials were agitated and alarmed by Tompkins’s presence. (“Their entrance into the city was so sudden and unexpected that it was regarded as an act of hostility,” Mayor Herrera would later explain.)

General Lozano asked Tompkins why he had come. Tompkins responded that he had been invited into the city by Captain Mesa, who was supposed to have sent a message in advance notifying the town officials of their arrival. Lozano said he had received no such message and emphasized that Tompkins and his men would have to leave immediately. Tompkins replied that they would go, but not until they had received the food and forage they had been promised.

Lozano called a man to his office to arrange for the supplies. As they were finishing their business, Tompkins heard a ruckus and looked out to see a mule hitched to a heavy cart bolting down the street, which he interpreted as an effort to cause confusion among the soldiers. “A big Yank grabbed the mule by the bit and stopped that little act,” remembered Tompkins. “This incident was so indicative of treachery that I slipped my holster in front in anticipation of immediate need.”

By the time Tompkins and Lozano had reached the street, a huge mob led by a beautiful young woman named Elisa Griensen had gathered. “Viva Villa! Viva México!” they shouted. As the troops started out of town, other women leaned out of their second-floor windows and dumped their slop jars and spittoons onto the soldiers. Tompkins was infuriated and dropped behind to keep an eye on the crowd. One compactly built man, with a neat Vandyke beard and mounted on a very fine Mexican pony, seemed to be exhorting the mob to violence. “Todos! Ahora! Viva México!” he shouted. Tompkins thought the man looked German and made up his mind to shoot this “bird” first if violence did erupt. Then Tompkins did something that seemed totally out of character: wheeling his horse around, he shouted, “Viva Villa!” If his aim was to confuse, he momentarily succeeded. The mob stopped and laughed. Then it surged forward.

Lozano was at the head of the U.S. troops, leading the soldiers in a northeasterly direction out of Parral. They were moving toward the railroad tracks and a depression between two smallish hills when gunfire erupted at the rear of the cavalry column. Tompkins realized his troops were being fired upon by someone in the crowd and raced ahead to notify General Lozano. “Los hijos de la chingada!” cursed the general, retracing his steps. Lozano slashed at the mob with his saber and another Carrancista officer fired into the crowd, shooting four or five people. The Parral residents instantly turned their wrath on the Mexican soldiers, yelling obscenities and throwing fruit and stones at them.

The ever-suspicious Tompkins thought Lozano had been deliberately leading them into a trap and ordered two groups of troopers to take the two hills. Then he deployed his rear guard under First Lieutenant Clarence Lininger along a railroad embankment. While the troops were moving to their new positions, a group of Carrancista soldiers had gathered on a third hill some six hundred yards to the south. Lozano begged Tompkins to retreat at once. But Tompkins would not be budged: After we get our food and forage, he responded. The Mexican troops on the hill advanced toward them. Tompkins stood and waved his arms and screamed at them to go back. When they refused, he ordered a captain and three armed men to drive them back and to fire upon the Mexican soldiers when they had them within range.

Tompkins decided his first target would be a soldier waving a Mexican flag. He turned and borrowed the rifle of Sergeant Jay Richley, who was lying behind him, his forehead peeping above the railroad embankment. When the flag suddenly disappeared from sight, Tompkins turned to hand the rifle back to Richley, but the young man was dead—a bullet had struck him in the eye and passed out the back of his head.

Now the fight began in earnest, and Tompkins, who had been secretly yearning to do something more than threaten to burn a poor man’s house down, was ready. With Mexicans converging on his flank, he realized their position was extremely vulnerable and ordered his men to withdraw across country toward the dirt road leading north to the small village of Santa Cruz de Villegas (not to be confused with Santa Cruz de Herrera, where Villa was holed up). As the main body retreated, Tompkins flung a line of troopers across the road to fend off the Carrancistas, who continued to follow them for the next sixteen miles. The U.S. forces were outnumbered by three to one and forced to fight a rearguard action the entire way.

Before they had reached the dirt road, Private Hobart Ledford, a tenderhearted man who had befriended a little white dog on the way to Parral, was shot through the lung and toppled from his horse. The detachment’s medical officer, First Lieutenant Claude Cummings, leaped off his mount and dressed Ledford’s wound while bullets sputtered into the ground. Cummings managed to get Ledford back onto a horse and then he turned to minister to Corporal Benjamin McGhee, who been shot in the mouth and was bleeding profusely.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Lininger and his eight men continued to hold the Mexican troops at bay while the main body retreated. The Mexicans returned the fire, but their aim was so inaccurate that Tompkins’s men were able to withdraw in an orderly fashion, marching two abreast down the road.

Enraged by the deaths of their fellow soldiers, the Carrancistas continued to dog the U.S. forces, traveling parallel to the road that the Americans were on. The land was flat and rolling, the fields separated by stone walls four feet high and four to six feet thick. At each wall, the Mexicans had to dismount, remove the stones, get back on their horses, and gallop to the next barrier.

Tompkins’s aide, Lieutenant Ord, noticed that Hobart Ledford, the lung-shot private, had fallen off his horse again. He raced back and pushed Ledford onto the mount. Slowly they returned to their lines, with Ord holding Ledford on one side while a second soldier propped him up on the other. Major Tompkins followed the threesome, urging Ledford’s horse forward with his whip. “Ledford begged us to go on and leave him. His agony was great,” remembered Tompkins. “I gave him a pull from my canteen, told him the ranch was just ahead, to hold on for five minutes more and we would have him where the doctor could make him comfortable.” Moments later, another bullet slammed into Ledford, entering through his back and coming out near his belly. He tumbled from the horse dead. The three soldiers hurried to catch up with their disappearing column, leaving the young man’s body where it had fallen.

Convinced that the Carrancistas would make one last charge, Tompkins deployed his men across the road. “In a minute or two they came,” he wrote, “without formation, hellbent-for-election, firing in the air, yelling like fiends out of hell and making a most beautiful target.” The U.S. soldiers went into action and Mexican soldiers and their mounts rolled in the dust, screaming in agony; only a few Carrancistas managed to check their horses and turn away at the last minute.

Upon reaching the village, Tompkins ordered his best marksmen onto the roofs and sent other soldiers to try to make contact with the American columns that were marching behind them. The Carrancistas gave no indication that they were about to give up the fight and Tompkins suddenly had images of the Alamo in his head. But when one of the army’s best rifle shots picked off a Carrancista sitting on his horse eight hundred yards away, the Mexicans stopped their advance.

Soon a messenger carrying a white flag and a note from General Lozano rode into Tompkins’s camp. “I supplicate you to leave immediately and not bring on hostilities of any kind,” the Mexican general wrote. “If on the contrary, I shall be obliged to charge the greatest part of my forces.” Tompkins dashed off a response in which he laid the blame for the altercation on the Mexicans:

I have just received your letter and regret very much that you were unable to control your soldiers. We came to Mexico as friends and not as enemies. After you had left us, I awaited in good order for the grain and fodder contracted for. When your soldiers, without provocation, fired upon mine, killing one and wounding two, as from this moment it became a question of self-defense, I also opened fire to permit my main body to retire, it still being my intention to avoid a general fight. It was your soldiers who followed me five leagues firing at every opportunity. I did not answer their fire until those who fired came dangerously near.

He added that he was willing to continue his journey north, provided that he would not be molested. Two hours later, the besieged troops heard a trumpeter from Colonel Brown’s Tenth Cavalry bugling Attention followed by Officer’s Call. The trumpeter for the Thirteenth answered, his wavering notes going out across the darkening plain. Once the U.S. soldiers realized the fight was over, they grew exhilarated, but many were saddened, too, by the deaths of Hobart Ledford and Jay Richley and the suffering of Benjamin McGhee, who would soon die from his wounds. (In addition to these three fatalities, a fourth soldier would eventually be listed as missing in action.) The skirmish also took its toll on the horses, with five killed and sixteen wounded.

Two days later, Major Howze and his exhausted troopers of the Eleventh Cavalry reached the Tompkins camp. In all, his squadron had marched 691 miles since leaving Columbus. One man had been killed and four wounded, and thirty-six horses and five mules were dead.

A few days later, Parral’s mayor, José de la Luz Herrera, rode out to the cavalry camp to apologize for the incident. Herrera wanted Villa captured or killed as much as the Americans; his two sons, Maclovio and Luis, had fought under Villa, but had switched sides when Villa broke with Carranza. The elder Herrera had publicly declared Villa a bandit and knew that his life was in danger as long as the rebel leader lived. Nevertheless, Herrera still believed that Tompkins provoked the fight by going into town unannounced. The mayor also pointed out that it was the citizens of Parral—not the Carrancista troops—who were the aggressors. Here again, he was telling the truth, although it was doubtful that cavalry officers believed him. After the U.S. troops had withdrawn, some thirty Parral residents who were purportedly sympathetic to the Villistas were arrested and two would eventually be executed.

Troopers from the Tenth and Thirteenth regiments retrieved the body of Hobart Ledford. His corpse had been stripped of shoes, pants, shirt, and valuables, but the little white dog was still at his side. The animal had been without food and water for nearly twenty-four hours. Touched by its loyalty, the soldiers adopted the dog as the official mascot of the Thirteenth Cavalry’s Troop M.

Ledford’s body was wrapped in a blanket and buried in the local cemetery, along with a sealed bottle that contained his name and military record. Lieutenant Lininger composed his eulogy and recited the Twenty-third Psalm. Three volleys and taps followed. The next day, Jay Richley’s body, enclosed in a casket, was brought by hearse from the town of Parral and was also interred in the cemetery. Over the next ten months, the army’s Burial Corps would make repeated trips into Mexico to recover the bodies of some thirty-one soldiers or civilians who had died on the expedition. But for some reason, six bodies were left behind. One of them was Private Ledford.

THE NEWS OF THE PARRAL FIGHT reached Washington first. On April 13, with Pershing still ignorant of what had happened, Secretary of State Lansing received two notes, one from Carranza’s secretary of foreign relations and another from Don Venustiano himself, protesting the incident and blaming it on Tompkins’s “imprudence.”

Pershing finally learned of the situation on April 14 when Benjamin Foulois, who had gone to Chihuahua City with dispatches, hurried back to give him the news. “Uh,” he grunted, rubbing his chin in characteristic fashion. But he was furious and told the correspondents that they could write whatever they wanted. “Nothing should be kept from the public. You can go the limit,” he declared. Pershing dispatched two members of his headquarters staff to investigate the incident, instructed all cavalry columns in the field to make haste toward Parral, and ordered the Sixth and Sixteenth infantries and the Fourth Field Artillery to start south from the base camp at Colonia Dublán. Tompkins rejoiced to see the reinforcements. “We now felt as though our force was strong enough to conquer Mexico, and we were hoping the order to ‘go’ would soon come,” he wrote.

But Pershing realized that he could not keep the soldiers there for long. With the Carranza government still adamantly opposed to allowing the Punitive Expedition to use its railroads, it would soon become nearly impossible to feed the men and animals converging on Santa Cruz de Villegas, which was 484 miles from Columbus. The combined cavalry units consisted of 34 officers, 606 enlisted men, 702 horses, and 149 mules. The animals alone required six tons of hay and nine thousand pounds of grain daily to say nothing of the two thousand pounds of food required by the humans.

Pershing decided he had no choice but to order the troops to move north, at least temporarily. “On Saturday, April 16, 1916, we piled in the cars and headed toward our own border. We drove all day and all night. Pershing sat grim and silent, his big frame taking the jounces of the rocky trails. He was suffering from indigestion,” Frank Elser wrote.

The hunt for Pancho Villa had come to a standstill. “Whether the halt is to be permanent or not depends upon circumstances beyond the control of General Pershing,” wrote Elser. “But from a military standpoint he has for the time being come to the end of his lane.”

EVEN BEFORE the Parral incident, President Wilson’s cabinet had been debating the question of how long Pershing should remain in Mexico. Secretary of State Lansing and Secretary of War Baker thought the troops should be withdrawn before a full-scale war between the two countries erupted, with Baker voicing the opinion that it was “foolish to chase a single bandit all over Mexico.” General Scott was also in favor of withdrawing the troops, pointing out that Pershing’s orders had been merely to disperse and punish the marauders and that the objective had been accomplished in a “very brilliant way.” But Wilson’s attorney general, Thomas Gregory, and Franklin Lane, secretary of the interior, thought Pershing should remain where he was until Villa was captured or until Carranza could prove to them that he could control the raids across the border.

Wilson himself was conflicted about what to do. Although he found the First Chief infuriating, he had no desire to see him fail and knew the presence of the U.S. troops in Mexico was destabilizing his presidency. But the border was still lawless and Pancho Villa was still at large. Wilson worried that a premature withdrawal might make the United States appear weak, not only to its southern neighbors but also to Germany. In addition, he was reluctant to give interventionist opponents such as Senator A. B. Fall ammunition in an election year. After Parral, however, Wilson knew there was no way that the troops could be withdrawn. National honor was at stake. The Punitive Expedition, he decided, would have to remain in Mexico for a while longer.

The president’s decision was fraught with risks. Military troops on both sides were edgy and one wrong move could ignite a war. And the American officers in the field were beginning to think that a larger war might not be a bad thing. While Pershing jounced north in his touring car, munching on crackers to stanch his indigestion, he was silently formulating a plan to pacify the state of Chihuahua and then the whole country. Once he was settled in his new camp, he sent a telegram to General Funston laying out a litany of complaints against the Carrancista government. “My opinion is general attitude Carranza government has been one of obstruction. This also universal opinion army officers this expedition. Carranza forces falsely report attacks against Villa’s forces and death of Villa leaders. Activity Carranza forces in territory through which we have operated probably intentionally obstructive. Marked example obstruction refusal allow our use of railroads. Captious criticisms by local officials against troops passing through towns prompted by obstructive spirit.”

The columns, he continued, were often delayed when hot pursuit was important and he noted that the Guerrero fight would have been a success but for the “treachery” of the Mexican guide. The natives, he wrote, had also obstructed their efforts to catch Villa at every opportunity, circulating false rumors and even going so far as to help him escape. “Inconceivable that notorious character like Villa could remain in country with people ignorant his general direction and approximate location. Since Guerrero fight it is practically impossible obtain guides even from one town to another except by coercion.”

Pershing also reported that the animosity toward the U.S. troops was growing. “At first people exhibited only passive disapproval American entry into country. Lately sentiment has changed to hostile opposition.” The de facto government was in a complete shambles and unable to control the local warlords, he added. “In fact anarchy reigns supreme in all sections through which we have operated.” He concluded the telegram with the following suggestion:

In order to prosecute our mission with any promise success it is therefore absolutely necessary for us to assume complete possession for time being of country through which we must operate and establish government therein. For this purpose it is imperative that we assume control of railroads as means of supplying forces required. Therefore recommend immediate capture by this command of city and state of Chihuahua also the seizure of all railroads therein, as preliminary to further necessary military operations.

Following up on his idea, Pershing two days later sent a second telegram to Funston outlining how U.S. troops could take control of the entire country. Soldiers from Fort Bliss could seize Juárez, he suggested, and working in tandem with his own men, they could drive the Mexicans south. Once Chihuahua City was taken, he recommended taking Torreón in order to secure Monterrey and other points to the east. “The tremendous advantage we now have in penetration into Mexico for 500 miles parallel to the main line of railway south should not be lost. With this advantage a swift stroke now would paralyze Mexican opposition throughout northern tier of states and make complete occupation of entire Republic comparatively easy problem.”

To Funston, Pershing’s suggestion wasn’t particularly radical. On April 10, two days before the Parral attack, he had telegraphed the War Department, asking to lead a new expedition into Mexico starting from Marfa, Texas. His request was curtly denied by the War Department, which noted that a second incursion into Mexican territory would engender certain “political difficulties.” The cooler heads within the War Department also quashed Pershing’s plan. General Tasker Bliss later attributed the ideas to the army’s sense of frustration and its desire to capture “something, someplace anything!”

Parral was the farthest south that U.S. troops penetrated into Mexico and the clash there marked the end of the first phase of the Punitive Expedition. Occurring only a month after the troops had crossed the border, the skirmish also marked a turning point in the military logistics. Pershing dissolved the columns and ordered the men to reassemble under their original regiments. Then he divided the occupied territory into five districts, with each regimental commander charged with policing a district and destroying any scattered remnants of Villa’s army. He issued the following instructions to his officers:

It is also desirable to maintain the most cordial relations, and cooperate as far as feasible, with the forces of the de facto government. Experience has taught, however, that our troops are always more or less in danger of being attacked, not only by hostile followers of Villa, but even by others who profess friendship, and precaution must be taken accordingly. In case of unprovoked attack, the officer in command will, without hesitation, take the most vigorous measures at his disposal, to administer severe punishment to the offenders, bearing in mind that any other course is likely to be construed as a confession of weakness.

With the American troops out of the way, Villa could now concentrate on getting well. Some historians maintain that Villa mounted a burro and proceeded to a cave known as Cueva de Cozcomate. But intelligence officers for the Punitive Expedition believed that Villa remained at the Rodríguez ranch until the first of June. Whether he was actually in the house where the Yaqui Indians were seen leaving is unknown, but he did tell a Japanese businessman, who worked as a “confidential agent” for the army, that he had watched in alarm as U.S. troopers searched the houses. “It was the closest call to capture I have ever had in my life; I was actually in very great danger.”

As for his generals, Nicolás Fernández and Francisco Beltrán continued south to the state of Durango. Pablo López remained hidden in a cave while his brother, Martín, drifted toward their hometown of San Andrés. Candelario Cervantes and his men loitered in the hills west of Guerrero, watching the American troops with field glasses. And Juan Pedrosa received some medical treatment from a French doctor and went into seclusion at a home that was just a few miles north of General Pershing’s advance base at Satevó.