AS SUSAN MOORE was drifting off to sleep, the Mexican soldiers were being kicked awake by their jefes. They rose instantly, blinking back the dreams and the fatigue-induced hallucinations that danced at the corners of their vision. In silence, they ate their tortillas and fetched the ponies. The little animals opened their mouths docilely as the metal bits were shoved between their teeth and the girth straps tightened. No mediating layer of moisture existed between the troops and the night sky and the air was very cold. The soldiers stamped their feet and shook the numbness from their hands. Most had no idea where they were going, but the knowledge of an impending battle had spread among them. Some sang mournful songs; others developed mysterious flus and stomachaches. The devout murmured prayers to the Virgin of Guadalupe and the soldiers who were resigned to their fate composed farewell messages for their families. Only the half-witted fiddler, Juan Alarconcon, seemed himself. He longed to put his bow to his fiddle in the shining dark and strike up an inspiring rendition of “La Cucaracha,” the División del Norte’s old battle song, but was told that he would be shot if he did so.

Maud noticed that Pancho Villa had changed into a uniform and was riding a spirited paint stallion that had been taken from the Palomas ranch. Earlier that day, Nicolás Fernández had approached her with a rifle. Maud felt certain her time had come, but instead of killing her, he wanted her to take the rifle and use it against her countrymen. Maud refused, saying the first thing she would do was shoot him and every other officer. He laughed, saying he believed her, and walked away.

Whatever doubts Villa may have harbored about the attack, he didn’t share them with the rank and file. Bunk Spencer, the African-American hostage, would later tell newspaper reporters that Villa gave a demented, rage-filled speech. “He told the men that ‘gringos’ were to blame for the conditions in Mexico, and abused Americans with every profane word he knew because the Carranza soldiers were allowed to go through the United States to reach Agua Prieta, where Villa was defeated. He didn’t talk very long, but before he got through, the men were crying and swearing and shrieking. Several of them got down on the ground and beat the earth with their hands.”

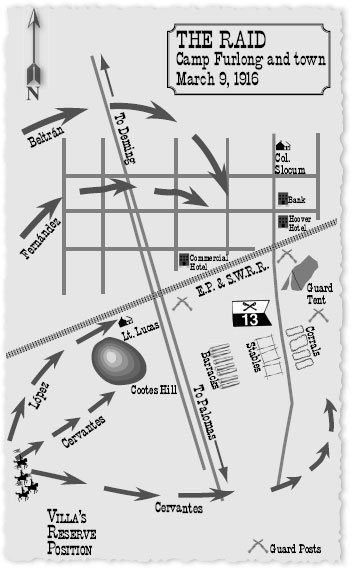

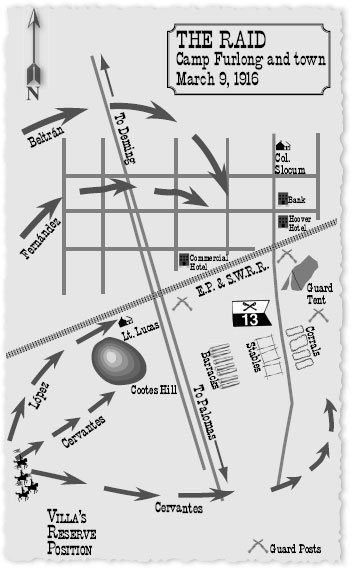

The column began marching slowly across the country in a northerly direction, retaining the same formation that they had on the long journey up from Mexico. Two small groups of soldiers were positioned at different points near the border to cover Villa’s retreat, leaving approximately 450 men in the main body. At some point prior to the attack, fences had been cut along the border and the railroad’s right-of-way to facilitate the Mexicans’ escape from the United States.

When they reached the international boundary line, about two miles west of Columbus, Maud saw five lights. Two appeared to be moving toward each other and greatly frightened some of the soldiers, who considered them bad omens. They soon realized they were merely the headlights of trains moving in opposite directions. The three stationary lights were fires to help guide their entry into town.

Crossing the border, they rode north up a deep arroyo that hid them from anyone who might be watching. Near a railroad bridge that spanned the arroyo, they paused for a few minutes while a train passed by. “We were finally so close to the tracks that when the train passed, we were able to see the passengers in the coaches,” Maud remembered.

They then resumed their slow, stealthy march eastward across the flat open country until they reached a point roughly a mile and a quarter west of a small rounded knoll known as Cootes Hill. It was the only hill of any size in the Columbus area and allowed them to prepare for the attack undetected. It was now about three o’clock on the morning of March 9, Villa’s favorite time for attack. He and his officers reviewed the troops and picked out the men who would participate and those who would be left behind to hold the horses. As usual, they were short of ammunition, so the horse holders were ordered to turn their bullets over to the selected raiders. (The Mexican troops were notoriously bad shots; few had marksmanship training or knew how to use the sights on their rifles.)

The plan called for a three-pronged assault, with the Mexican troops converging on Camp Furlong and the town simultaneously from the west, north, and east. The right wing, composed of Candelario Cervantes’s troops and half of Villa’s personal escort, would occupy the knoll and continue forward into the military encampment. Some of these soldiers were to swing counterclockwise around the military post and take the horses stabled on the east side of the camp. Pablo López and his men would make up the center wing and use the railroad tracks to guide them into the town. The left wing, commanded by Nicolás Fernández and Francisco Beltrán, was to circle around the town and come down from the north and northwest.

In one of the last orders of business, Villa announced that Colonel Nicolás Fernández had been promoted to general. Then he gave the order for the men to dismount and advance on foot.

Vámonos, amigos!

Viva Villa!

Viva México!

Matemos a los gringos!

Hundreds of armed soldiers streamed through bushes toward town. Soon the percussive explosions of the Mexicans’ Mausers alternated with the pop-pop of the cavalry troopers’ Springfield rifles. The high-pitched Mexican bugles dueled with the lower-pitched cavalry bugles, which were frantically rallying the American soldiers to arms. From somewhere near the top of the knoll came the first ghostly strains of “La Cucaracha.” And a few blocks to the northeast, Colonel Slocum bolted up in his bed. “My God, we are attacked!”

LIEUTENANT LUCAS was awakened by the creak of leather and crept to the window, where he saw men riding toward the military camp. He recognized the intruders as Villistas by the hats they were wearing and judged that he was completely surrounded. Lucas grabbed up his pistol, thankful now that he had taken the time to load it, and positioned himself in the middle of the room, where he would have ample view of the door. He was sure he would be killed but if that was to be his fate, he figured that he would take a few of the Mexicans with him.

Before they had time to enter Lieutenant Lucas’s house, Fred Griffin, the young sentry posted in front of headquarters, spotted the invaders. He was standing perhaps 250 feet east of Lucas’s house and called for them to halt. The Mexicans charged toward Griffin, firing. Shot in the stomach, chest, and arm, Griffin managed to squeeze off a few rounds, killing two or three raiders before he collapsed. The diversion saved Lucas’s life, enabling him to get out of his house. He dashed past the headquarters building, where Griffin lay dying, and ran to the barracks, where he told the acting first sergeant to turn out his men and have them meet him at the guard tent, where the machine guns were kept. On his way to the tent, an armed Mexican suddenly appeared in front of him. Both men fired. When the smoke and noise died away, it was Lucas—one of the poorest shots in the regiment—who was still standing.

When he reached the guard tent, Lucas saw another young sentry sprawled across the door. He stepped over the soldier and fumbled in the dark to open the cabinet where the French-made Benét-Mercié machine guns were kept. The guns were in great demand on the black market because Mexican troops would pay as much as five or six hundred dollars apiece for them. One had disappeared from the Thirteenth Cavalry’s arsenal a few years earlier, and as a consequence they were always kept under lock and key. Weighing only thirty pounds, they were easy to carry, but difficult to feed in the darkness. Lucas and several of his men grabbed one anyway and set it up near the stables. Lucas fed the clip of bullets into the metal slot while a corporal acted as gunner. Almost immediately, the weapon seized up. Lucas and his men swore violently, picked up the gun, and raced toward the hospital, where they hoped to repair the weapon behind the building’s bulletproof adobe walls.

While Lucas was getting his machine guns and troops deployed, Lieutenant Castleman was running toward the barracks to rouse his men. It just so happened that the soldiers had recently been drilled in what to do in the event of a surprise attack and were already falling in. With about twenty-five men from Troop F, Castleman proceeded north toward the town, where his first priority was to check on his wife and make sure she was safe. As they advanced, the Mexicans poured heavy gunfire on them and the bright yellow flashes lit up the terrain with a surreal beauty. The Americans dropped to the ground and returned fire. “On account of the darkness,” wrote a young sergeant named Michael Fody, “it was impossible to distinguish anyone, and for a moment I was under the impression that we were being fired on by our own regiment, who had preceded us to the scene. The feeling was indescribable and when I heard Mexican voices opposite us you can imagine my relief.”

Incredibly, none of Castleman’s men were hit in the fusillade and they stood and began making their way north again. As they were crossing the railroad tracks, Private Jesse P. Taylor was shot in the leg. Fody told him to lie down and be quiet, promising that they would pick him up later. Ten yards farther, another private tripped, setting off his gun and giving himself a nosebleed, as well as alerting the attackers to their location. More gunfire rained down on them. Castleman’s men again dropped to the ground and returned the volley. When the onslaught lessened, they stood and advanced. “We made about four stands in about five hundred yards,” remembered Fody. “Private Thomas Butler was hit during the second stand but would not give up and went on with us until he was hit five distinct times, the last one proving fatal.”

Whether it was a deliberate part of Villa’s strategy or not, the regiment’s officers, who lived in the northwest and northeast quadrants, were now cut off from the camp by the hundreds of Villistas moving toward town. The officers were faced with a difficult choice: staying with their loved ones or trying to make it through the enemy lines to the camp, where their men were fighting alone. Each officer solved the dilemma differently.

Herbert Slocum decided he had to first get his wife to safety, and led her through the darkness to the adobe shack of their laundress. “The bullets were falling like rain,” Mary Slocum recalled. “We were so bewildered, Col. Slocum, even Herbert was. It seemed as if we were dreaming.”

In the northwest quadrant, Major Frank Tompkins, his wife, Alice, and two female houseguests grabbed mattresses off the beds and threw them in front of the door. “Our greatest fear, though unexpressed until later, was that they would set fire to the house and shoot us as we ran out,” Alice Tompkins said. Captain Smyser and his family, who lived to the southeast of the Tompkins family, concluded that their house wasn’t safe and slipped outside and hid in an outhouse. Soon they decided the outhouse wasn’t safe either and crept farther into the brush. Lieutenant William McCain decided to make a dash for the army camp and set off with his wife, small daughter, and orderly. On the way, they ran into Captain George Williams, who lived just a few blocks south of Colonel Slocum and had apparently decided to make a counterclockwise loop around the north side of the town in hopes of reaching the camp.

By now, other raiders were converging on Columbus from the east. Harry Davidson and his buddy, R. L. Carlin, both members of the Texas National Guard who happened to be in Columbus that morning, were sitting on a platform on the south side of the icehouse waiting for the train to El Paso when they heard Spanish voices. “We sat up and in the moonlight saw three Mexicans on horseback coming toward us. They were armed. We did not have a chance to get away. I said to Davidson, ‘It’s up to us to take ’em as they are’ and we sailed into them,” Carlin remembered.

It was an extremely reckless strategy since neither was armed. Harry Davidson was killed instantly when a bullet bored into his head. Carlin, now realizing the insanity of their decision, took off running. “The three men followed me, firing. I ran down the railroad track, zigzagging. Then I got into a ditch and made for the north across the field, crawling on my hands and knees whenever I got far enough ahead for it to be safe. The bushes were not high enough to give me much protection.” The Mexicans chased him for about three miles and then turned and galloped back toward the corrals and stables, where their companions were already rounding up the horses. Frank T. Kindvall, a farrier, rushed from his tent to protect the animals. It was a noble but suicidal move. “When we picked him up later,” said one of his friends, “it was hard to recognize him for he had been shot several times and rode over.” Another stable guard, though, caught one of the intruders and beat his “brains out with a baseball bat.”

WHILE THE FIGHT RAGED in the army camp, one group of Mexican soldiers advanced to the bank, a second to the train station, a third toward the Commercial Hotel. In the first minutes of the battle, the Mexican invaders were able to go about their looting in a leisurely way, halting occasionally to remove their rotting clothes and don the shirts and pants that they were stealing. Eventually they accumulated so much loot that they commandeered at least one buggy and several mules to cart off things they couldn’t carry. From J. L. Walker’s place, they hauled off saddles, bridles, spurs, bed blankets, saddle covers, razors, pistols, revolvers and gun scabbards, ammunition, shirts and socks. From the home of W. R. Page, they took a gray coat with a pair of gold spectacles in the upper pocket; a pair of “very fine quality” gray trousers; one pair of ladies’ shoes, tan, size five, A-; one black velvet hat trimmed in white ribbon; a gray cloth skirt; another pair of ladies’ shoes, these size six; sheets, pillowcases, napkins, handkerchiefs, socks, and men’s underwear. From Harry Casey, the jeweler, they took rings, lockets, chains, buttons, and gents’ cuff links; packages of rubies, sapphires, and emeralds; nine boxes of chocolates and one jar of chewing gum.

One detachment of Mexican soldiers was charged with finding Sam Ravel, the storekeeper the Villistas had imprisoned in Palomas. (“We did not go to Columbus to kill women and children as it has been said,” Juan Muñoz, one of the Villistas, told a Mexican author years later. “We went to Columbus to take Sam Ravel and burn his properties for the robbery and treason which he committed. Ésa es la verdad.”)

Ravel’s youngest brother, Arthur, just sixteen, was asleep when the soldiers burst through the door of the house where Ravel was believed to be staying. “No me maten!”—“Don’t kill me!” he screamed. They marched the boy to the family store, which was a block away. Louis Ravel, the middle brother, was asleep in the store and scurried into the back room and hid under a pile of hides. The intruders smashed in the windows, broke open the display cases, and took clothing, boots, shoes, hats, cigars, and candy. They instructed Arthur to open the safe. Abre la caja! they shouted. But Arthur didn’t know the combination, and in frustration, they grabbed him by either arm and escorted him down the street toward the Commercial Hotel, where they hoped to find Sam Ravel. Near the hotel entrance, Arthur saw other armed Mexicans milling about. Candelario Cervantes was the officer in charge. He shouted, “No molesten a las mujeres, pero maten a todos los gringos!”—“Don’t harm the women, but kill all the men!”

The invaders hammered on the door. Laura Ritchie, who had seen a guest off on the 2:45 a.m. train, was the first to recognize that the hotel was under attack. She heard the sound of breaking glass, wood splintering, staccato bursts of Spanish, and a volley of shots that sounded like a handful of rocks being thrown at the hotel.

Moving with the slowness of dreamers, the Ritchies donned what clothes they could find and gathered up their three daughters. They stumbled into the hallway and encountered the frightened faces of their guests: Rachel and John Walker, Charles DeWitt Miller, Harry Hart, Uncle Birchfield, and José Pereyra. The guests, too, moved slowly, their limbs numb and their heads so clogged with sleep that they could not yet grasp what was going on. Who were all these half-dressed strangers? Why were they milling about in this narrow hallway? And what was that noise down below?

William Ritchie tried to calm them, his wife remembered, “telling them what he thought it was, of course, they were all strangers at the hotel, he tried to tell them the best he could, he thought it was an attack on the town, all this time this shooting was going on, I can not tell you how it sounded. I cannot explain the noise, then after that they called ‘Viva México’ and we all ran out to the front of the hotel, the lobby, to see what we could see.”

Since the hotel was on the second story of the building, there was no way to escape except by the front or back exits, which were blocked now by the Mexican troops. Several of the men had guns, but William Ritchie was afraid the raiders might set the building on fire if they used them. Instead, he dashed downstairs and bolted the front door, hoping that they would be safe until the American soldiers arrived. But a few moments later, the door burst open and the raiders thundered up the stairs.

The sight of the soldiers only increased the feeling among the guests that they were dreaming. The Villistas were unlike any humans they had ever seen: sun blackened and unshaved, smelling of horse sweat and smoke, pants held up with twined horsehair, sandals and shoes made from untanned cowhide. At the end of their rifles were bayonets and perhaps it was their dull points that prodded the hotel occupants into wakefulness.

Señor Pereyra stepped in front of the women and begged the Villistas not to shoot, saying that they were all Mexicans. No disparen, por favor! Somos méxicanos aqui! The soldiers dragged each of the women into the light and asked in disbelief, Es ésta una méxicana?

In their harsh voices, so absent of the courtesy of the Spanish language, the attackers demanded money and jewelry. Uncle Birchfield, the wily old cattleman, scolded them: Cállate! Cállate!—Quiet! Quiet! he said, as he began writing checks.

William Ritchie gave the intruders his watch and fifty dollars. His wife struggled to remove her rings, but the Mexicans grew impatient. One tore the locket from her neck. Another struck her hand with the butt of his pistol, a third clubbed her in the side. While the guests were being robbed, other raiders were smashing trunks and valises and pawing through clothes. Blanche Ritchie watched in horror as a dirty soldier stuffed her pink dress and black patent-leather shoes down his shirt. The troops fired their weapons into the bureaus and beds and demanded to know where Sam Ravel was. Dónde está Sam Ravel? they shouted. Laura Ritchie was dragged down the hall and ordered to unlock Sam Ravel’s room. But luck was with the inhabitant of room 13; he was still in El Paso.

The light in the corridor was a queasy yellow. With each tic of fear that the guests displayed, the Mexicans found their own cruelty increasing. Using Arthur Ravel as interpreter, the Mexican soldiers asked the male guests to go downstairs to meet their commander.

Charles DeWitt Miller, wearing one laced boot, a brown wool shirt, and khaki pants, descended the stairs. He may have thought of his two little girls, ages two and four, who would one day watch the snow fall on the Sandia Mountains and wear flowered chiffon gowns to college dances, and his wife, Ruth, who would cry bitterly when she received his postcard. Miller stepped into the street.

“Éste es gringo—mátalo!” the officer commanded. As the Mexicans raised their rifles, Miller bolted toward his low-slung touring car and managed to jump in and slam the door. When he tried to start the engine, a bullet sped through the door and pierced his body. He slumped across the seat.

Harry Hart, the veterinarian, was second down the stairs. He was wearing pin-striped trousers and his ruby and diamond ring, which the invaders had somehow overlooked. The Mexican soldiers waved their guns in his face and told him to run. As Harry Hart began to run, no different from the cattle he had inspected that day, the commander ordered his troops to kill him. Shots rang out and Hart fell motionless in the street.

John Walton Walker, contractor, rancher, and hay farmer, was next. His young wife, Rachel, was determined not to let him go and clung to him on the stairs. A Mexican soldier dug his fingers into her arm and yanked her back up the steps. As John Walker turned to look up at his wife, a gunshot blast to the chest sent him reeling out the door.

“They have killed him!” Rachel screamed. She continued to scream, only adding to the terror and confusion of the remaining hotel guests. She grabbed the hand of Mrs. Ritchie’s eldest daughter, Myrtle, and said, “Come with me. I must go and see if I can find my husband.” They went out on the upper porch of the balcony and looked down, where she saw John’s body lying in an immense pool of blood.

“There he is! There he is!” Rachel yelled, her voice filled with hysteria. She called to her husband but knew intuitively that he was already dead. With some effort, Myrtle managed to drag her back into the hotel, afraid that Rachel was going to “jump from the porch to her husband’s body.”

Now it was time for William Ritchie, white-haired and dignified, with the thin red skin of a very old man, to begin his descent to the firing squad. As he slowly raised his hands into the air, he may have thought that it was his own restless nature, urging him forever onward, that had brought him to this moment. Ritchie had taken to heart Horace Greeley’s advice and had moved his family farther and farther west. By sea, they had journeyed to New Orleans. By rail to McKinney, Texas. By rail again to Porterville, Texas, a town that would dry up and leave no trace of its existence, and finally to Columbus. Not until William Ritchie had built the hotel and five rental houses was he able to rest, and begin to appreciate the joys of a settled life.

To the Mexicans, he said, “I cannot go and leave the women and children to protect themselves.” But his protestations fell on deaf ears. “They put their hands on him,” remembered his wife, “and forced him down there; they told him he would have to go and he found out he had to go, and they took him down, and my daughter put her hand out and says, ‘Don’t go, daddy; don’t go.’ He says, ‘I will be back in a minute.’” At the foot of the stairs, the Mausers roared.

In the brief pause that followed, the Villistas heard the growing battle in the direction of the army camp. The machine-gun fire—el tableteo de una ametralladora—especially caught their attention, and they decided to withdraw from the hotel, taking José Pereyra and Arthur Ravel with them. Some of the Villistas marched the Ravel boy toward the Columbus State Bank. “No lo matamos todavía”—“We’re not going to kill you yet,” one growled to Arthur. They walked past William Ritchie’s bleeding body. “He said, ‘Humph,’ just like that,” Arthur remembered. The Mexicans gave him no notice.

NOT FAR FROM the Commercial Hotel, Milton and Bessie James and their two houseguests cowered in the darkness, listening to the rat-tat-tat of rifle shots alternating with the long, rolling thunder of the machine guns. When a bullet shattered a lamp, they became convinced the wooden walls would not adequately protect them and decided to make a dash for the Hoover Hotel, which was three hundred feet away and made of thick adobe bricks. They flung open the door and began to run. On the far left was the little girl, Ethel, then came Bessie, then Milton, and finally his stepsister, Myrtle Wright Lassiter. They held hands, clasping one another, as if the physical bond would protect them from the swarm of bullets that lifted the dirt at their feet.

They sprinted toward the adobe hotel, ghost colored and floating like a ship in the first glimmer of morning. Coming toward them down Broadway Street was a crowd of Mexican soldiers. The troops raised their rifles and screamed, “Viva Villa!” “Viva México!”

Milton was hit once, then a second time. He began to fall, folding himself around a fiery redness that had materialized somewhere below his waist. On his left, he saw Bessie, leaping into the air, her eyes round as those of a caught fish. On his right, Myrtle staggered against some invisible current and then was sucked under. Only the little girl, Ethel, made it safely through the hotel door.

Ethel told Will Hoover, the big-bellied man who owned the hotel and who also happened to be mayor of Columbus, that the Mexican soldiers had killed her sister. William Hoover and his mother, Sarah, crept down the hall to the office. Cautiously they looked out the window and saw their dear neighbor, Bessie, groaning in the sand. William Hoover was very frightened, but he took a deep breath, opened the door, and dragged Bessie back into the hallway. His mother stood by with a blanket, begging God to spare them. They could see the Mexicans in the street firing indiscriminately at the windows and doors. “Why they did not shoot into the hall, was God’s answer to my earnest prayer,” Sarah Hoover later wrote.

Bessie’s skirts were soaked with blood. She had been shot twice, once in the abdomen and once through the chest. With William and Sarah Hoover crouched over her, the young woman murmured, “I am safe,” and died.

Will Hoover and his mother returned to her room, where the rest of the family lay on the floor. It was the safest room in the hotel because the raiders couldn’t shoot directly in. Charlie Miller, the druggist, lived in one of the upstairs rooms. During a seeming lull in the fighting, he grabbed up his keys and decided to check on his business. As he opened the hotel door, wrote Sarah Hoover, “They shot him and he fell back dead in our office.”

In a tiny house next to the Hoover Hotel, Susan Parks, a nineteen-year-old telephone operator, cowered with her baby daughter, Gwen. When she peeped out the window, she saw a Mexican officer giving orders:

A bugler stood beside him and a little farther off was a drummer. The man in the uniform was Villa. I am absolutely certain of it. He was dressed in a brigadier’s uniform with a cap on in front of which was a medallioned Mexican eagle worked in gold braid with a black background. I have seen so many pictures of the man that there is no possibility of mistake. His beard was about two inches long. If I had not been sure of recognizing him by his features, the proof would have been in the way the Mexicans came dashing up to him every minute or so for orders.

Villa’s exact position during the raid has been a matter of controversy for decades. Some Mexicans who were captured said that he remained at the rear, directing the fight. Others argue that he was superstitious about dying on U.S. soil and hovered just on the other side of the international border. But Maud Wright insisted that Villa was mounted on horseback and entered Columbus with his officers.

Mrs. Parks grabbed up her little baby girl and crept to the switchboard. When she lit a match to see the instruments, bullets shattered the window, covering them with glass and splinters. On her hands and knees, she crawled back across the room and put the baby under the bed and then returned to the switchboard and began dialing the number for the U.S. Army at Fort Bliss.

ALL OVER COLUMBUS, in the wooden houses that rose tentatively from the desert floor, the residents were making life-and-death decisions. Should they flee? Should they stay? Would the marauders burn them alive?

Archibald Frost and his wife, Mary Alice, lived in a modest home behind their furniture store with their four-month-old son. Archibald thought the best place to hide might be the store basement. “I realized by the bullets flying around it was an attack of some kind, and I thought possibly that we had time to get into the store and get in the cellar.” He grabbed his pistol and his wife held their infant son. Together they crept around to the front of the store. “We had to pass through what seemed to me was machine gun fire. The bullets sang as they came through the air. And there seemed to be many of them in the air at the same time,” Archibald later said. He unlocked the door and Mary Alice dashed inside with the baby. Archibald returned to the porch and looked in the direction of the gunfire. “It was to the west and southwest of me and there were so many guns firing that it caused a halo for a space of about a block, the light of the flashes from the rifles. Previously to that I had heard a bugle, it must have been a Mexican bugle, for its call was different from any bugle call I had ever heard, and was beautiful to listen to.”

As Frost started across the porch, a bullet slammed into his right shoulder and knocked him to the ground. On his hands and knees now, he crawled into the store as bullets shattered the windows behind him. Once inside, Frost realized that the cellar might not be a safe place after all because the raiders could set the store on fire and roast them alive. Then he remembered his new Dodge Brothers touring car parked in a garage behind the store. “I whispered to my wife that I thought we had better get into the car there, and get started and beat it; she did not know I was even wounded at that time, so we walked out the back door and I managed some way to unlock the garage in the night.”

Frost’s car turned over readily enough. He released the brake, threw the machine into reverse, and started to manually push the automobile out of the garage. “Usually I give her one shove that sends her clear to the middle of the road.” This time, though, the car rolled back inside. He gave the car another shove and the vehicle hit the door. On his third attempt, he saw a Villista standing across the road. The soldier shot at Frost and Frost returned the gunfire. “This Mexican soldier continued to fire at us during the time the car was being backed down on him, stopped for gear shifting, and started forward again, except such times as he dodged back of our car to avoid being fired upon himself, when he seemed to be having things too much of his own way.”

As they raced down the dirt street, other raiders fired on them. A second bullet tore through Frost’s left arm, ricocheting off the bone before exiting. He kept his foot on the gas and gunned the car north toward Deming. He was bleeding heavily and soon grew so weak that he asked Mary Alice to take the wheel. She had never driven a car before and hit a bump with such force that her infant son was catapulted from the backseat to the front seat. Fortunately, he was unharmed. Only after they were in Deming did they examine the automobile and realize how miraculous their escape had been. Multiple bullets had pierced the metal behind the driver’s seat. Another bullet, clearly meant for his wife, had ripped through the leather cushion on the passenger side and struck the windshield. Frost’s clothing was soaked with blood. The front seat, side of the car, and its running board were also covered with blood. Marveling at their close escape, Archibald suddenly remembered something else: it was his thirty-fifth birthday.

James Dean and his wife, Eleanor, and their son, Edwin, twenty-three years old, lived north of the business district. When they heard the gunfire, James thought it was only the cavalry staging a mock battle. “If you have good sense, you will go to bed and get your rest,” he told his wife and son. Eleanor and Edwin dressed anyway. Edwin loaded a rifle and left it at the head of his parents’ bed and started down to the grocery store to get more guns and ammunition. Eleanor wanted to go to the home of their neighbor, R. W. Elliot, whose house was made of adobe. James told her to go ahead and that he would join her later. “So I went & he came but would not go in the house. We all tried to get him in but he wanted to watch. He would go over to the house & look around and then come back.”

As James paced back and forth, the attack on the small town intensified. The Mexicans set fire to the Lemmon and Romney general merchandise store and the flames soon leaped to the dry wood of the Commercial Hotel. James decided to go downtown and help put out the fires. “Mr. Dean, you can’t do that. Come back here. They’ll kill you!” screamed a neighbor. But he would not be deterred and disappeared into the night. Eleanor grew frantic with worry. She went home, built a fire, made coffee, and waited for her husband and son to return. “I knew there would be lots of wounded & they would need water & made coffee, so that any who needed it could be refreshed. I took some over to the others and drank a cup myself. . . .”

The Commercial Hotel began to burn rapidly, the fire stoked by the kerosene and gasoline stored in Ravel’s warehouse on the ground floor. Upstairs, Rachel Walker and Laura Ritchie and her three daughters ran from window to window looking for help. Laura Ritchie kept wondering where the U.S. cavalry was. “I wondered why—the soldiers had always been good to us—I wondered why they had not come to us; I wondered why somebody did not come to our assistance after our building had caught on fire.”

Suddenly up the back stairs came Juan Favela, the modest and gentle cowboy-rancher who had tried so hard to warn Colonel Slocum of the impending attack. “The hotel was afire. At that time my daughter, Edna, appeared at the back door; she darted back again and she said, ‘Oh, mamma, there is Juan Favela at the bottom of the stairs.’ She recognized Juan Favela’s voice, and he says, ‘Edna, come to me, I will take care of you.’ So we all went down.” Joining them was Uncle Birchfield.

Favela led the group down the stairs and across the alley toward an adobe hut that had already been ransacked. Edna suddenly remembered her canary and broke free and ran back up the stairs to retrieve the bird. But the cage was smashed and the canary already dead. Then she ran down the front steps to look for her father and saw his body lying in the street. “So it was Edna who brought back the sad news that our father, our wonderful, gentle, gay and lighthearted father was dead,” Blanche would later write.

Rachel Walker, irrational after seeing her husband’s body, remembered a man holding her, telling her she must get out, that the hotel was burning, and that she must not go down the front stairs as they were burning, too. Two men lowered her from a rear window with a blanket. When she was about half a block from the army post, an American soldier ran out from their lines and carried her to the post hospital, where she spent the remainder of the night, begging someone to go for her husband’s body.

One man did not escape with the others and his remains would be found in the rubble the following day. William Ritchie had registered him and Laura thought he was a soldier. “Any more than that, I do not know,” she said.

FROM ABOUT 4:30 TO 5:45 A.M., the battle raged. Horses stampeded through the streets and small groups of men could be seen fighting in the lurid light cast by the burning buildings. In the army camp, the cooks engaged in fierce, hand-to-hand combat with attackers who sought shelter near the adobe cookshacks. One group of Mexicans broke down a door only to find the cooks waiting for them with pots of boiling water and kitchen axes. A second group was dislodged from their hiding space by the shotgun pellets that the cooks used to hunt game. A third was raked by machine-gun fire.

Corporal Paul Simon, twenty-six, who played in the regiment’s marching band, was killed when a bullet crashed through the flimsy walls of the barracks. John C. Nievergelt, fifty, another member of the band, was shepherding his wife and daughter from their home to the camp when he was fatally wounded. Sergeant Mark Dobbs, twenty-four, one of Lucas’s machine gunners, was shot through the liver but remained at his post until he died from loss of blood.

Lieutenant Castleman and his troopers set up a skirmish line, with the Hoover Hotel on their left flank and the Columbus State Bank on their right. Nearby was Castleman’s own house, where many of the officers’ wives had taken cover. Using the light from the fires, they aimed their rifles down Broadway, methodically picking off the invaders. Lieutenant Lucas had three of the machine guns aiming north into the town from various points along the railroad tracks and a fourth trained on the corrals. Thirty riflemen were deployed along the railroad tracks facing the town. South of the railroad tracks, in a deep ditch that ran parallel to the Deming road, crouched Lieutenant Horace Stringfellow and his men.

An army account of the raid noted that Herbert Slocum managed to join his troops “about dawn,” which is consistent with what several eyewitnesses remembered. Louis Ravel, who had been hiding beneath the pile of hides, escaped out the back door of the store and ran into Slocum in front of the colonel’s house. Slocum asked the young man what was going on and Ravel told him “that the town had been attacked by Mexicans and was then in possession of the Mexicans, and that part of the town was burning. . . .”

Edwin Dean, who had wound up at the intersection where Castleman and his troopers were having good success at methodically picking off Villistas, saw Slocum coming down the street from the direction of his house. Castleman reassured Slocum that everything was under control and urged him to go home. “Everything is all right, Colonel, you had better go back. You can not do anything here.” Slocum “stood around and talked a little bit and then went back north,” Dean added.

Eventually Colonel Slocum made his way to the small knoll south of the railroad tracks, which the Villistas had used as a cover and landmark to coordinate their attack. Also converging on the hill were Lieutenant Stringfellow and Captain Smyser and Major Tompkins and some sixty other armed soldiers. Remembered Stringfellow: “Colonel Slocum had been shot at. He had a bullet hole transversely through the barrel of his revolver and began walking up and down the firing line on top of the hill with me at his side until I persuaded him not to risk his life so freely.”

Villa and his men had fallen back a thousand yards west of the knoll. Their identities were difficult to make out in the dawn light and Colonel Slocum ordered his men to momentarily hold their fire, thinking the soldiers might actually be their own cavalry troops coming from Gibson’s Line Ranch. Said Stringfellow, “Not having field glasses I had to take a chance, opened fire and then stopped to listen to the bullets. The Villistas went into action beautifully, dismounted as one and their return fire clipped the top of the hill but there was no ‘crack’ of the Springfields. These were Mexicans.”

MAUD WRIGHT was one of the first to realize that the battle was turning against the Mexican troops. A bullet struck the ground in front of her horse, another grazed its mane. “They began to bring the wounded back to the horseholders. They were placed on their blankets side by side where they lay groaning and crying. Many of them died right there,” she remembered.

Villa, she continued, “had been in the thick of the fight, for many times I heard his stallion squeal from some particularly noisy section of town.” At some point, she said, the stallion was shot out from under him and one of his soldiers dashed back and got a replacement horse. Before retreating, Villa galloped up and down among the disorganized and frightened soldiers, slashing from right to left with his sword, trying to make them stand and fight. A few did kneel and fire their rifles at the Americans, then began a fairly orderly retreat toward the border. Maud and her horse were swept up with them. Bunk Spencer, the other hostage, made his escape by lying flat on the ground, somehow managing to avoid being trampled.

One of the retreating Mexicans stumbled into Lieutenant William McCain’s party, which included his wife and young daughter. McCain raised his shotgun and fired. The Mexican fell to the ground, moaning, but still very much alive. McCain suddenly remembered that the gun was filled only with bird shot. He and Captain George Williams did not want to fire the gun again for fear of alerting other Mexicans so McCain tried to choke him, but the wounded man fought back ferociously and the little girl began to cry. Mrs. McCain tried to hush her and then handed her husband a pocketknife. “Slit his throat,” she whispered. McCain took the knife and hacked at the man’s throat but the blade was too dull. Finally, he tossed the knife away, and with his family looking on he picked up the shotgun and bludgeoned the Mexican to death.

Pablo López, who had directed the Santa Isabel train massacre, had been severely wounded near the Columbus train depot. A bullet had struck him in the middle of the chest, at the exact point where his bandoliers crisscrossed his body. The heavy leather straps kept the bullet from penetrating his chest but the impact knocked him from his horse: “As I was sitting on the ground, another came and went clean through both of my legs, from left to right, while still another broke the loading lever of my rifle. I thought it was time to go. A stray horse, also wounded, was standing by, and I crawled to it and dragged myself on it. Having lots of clips for my automatic, I kept emptying my pistol to protect my retreat. My comrades were riding southward, too.”

As the Mexicans withdrew, they continued to hear gunfire. “Por buen rato pelearon americanos contra americanos”—“For a time Americans were fighting Americans,” remembered Juan Muñoz. “They didn’t realize that we were retiring and they followed with thick fire; but not against us, it was against the people of the village, the ones who were already organized and had begun to fight.”

The Villistas galloped toward the border, passing Mooreview, where John and Susan Moore lived. “We rode past the ranch and I once again saw Villa,” recalled Maud. “He threw away an empty cartridge belt and pulled out his revolver and emptied it in the general direction of the soldiers. When those shots were gone he took off his hat and waved it defiantly at all of them. I sincerely believe he was unafraid and almost willing to fight the whole U.S. Army by himself.”

Once they crossed the international line, Villa rode back to Maud. Sweat streamed down his horse’s flanks and the animal’s dark eyes rolled, the whites grown wide with fear. He held his reins lightly while the horse plunged up and down.

Quieres regresar a los Estados Unidos?

Sí, por favor.

Bueno. Puedes irse. Te quedas con el caballo y la silla.

Maud did not argue. She took her horse and saddle and turned back toward Columbus. Her horse had been badly spooked by the gunfire and the smell of blood and kept trying to rejoin the horses that were fleeing in the opposite direction. Finally she dismounted and began leading the mare through the brush. “When I would pass Villistas, many of them would tell me good-bye and shake my hand, saying they were sorry that they had treated me badly. They actually acted as though I was their best friend.”

She had not gone far when she heard a voice begging in Spanish for water. It was Castillo, one of her guards, who had taunted her on the long northward march by telling her she probably would not be alive the next day. He had been badly wounded and her first impulse was to kill him. Instead, she took his saddle, which was much better than hers, and put it on top of her own. “I was sorely tempted to impale him on a sword, but instead asked him what he thought of the American soldiers now. He turned his head and I walked away, leaving him to die.”

She reached a small compound and went into the corral, watered her horse and drank deeply herself, and then walked toward the house. John Moore was lying dead in a pool of blood at the edge of the porch. She heard a faint noise and followed the sound out behind the house, where she came upon Susan Moore.

JOHN AND SUSAN MOORE had been sound asleep on their porch, buried under their heavy auto robe, when the attack began. Susan, the first to hear the gunfire, was so afraid for a moment that she couldn’t speak.

“Wake up. Look. Villa has come and is burning the town,” she finally whispered.

John Moore raised himself up on his elbows. Although they were several miles away, the orange flames were plainly visible against the black horizon. “You are right. We had better get dressed.”

Susan was already slipping on her clothes, grateful that she had taken the time to arrange them so carefully the night before. They tiptoed around the house and drew down the shades. Her husband returned to a pantry window, which faced the town. Susan stood next to him. Quietly, John said, “If I were in your place, I would not stand there. Someone might see you or you might be hit by a bullet.”

Susan moved back into the shadows and began walking from room to room, her eyes lighting upon the small beautiful things that she had brought with her to Columbus—the hand-painted vase, her linen table runner, the fancy bedroom clock that she had bought at Macy’s.

Imperceptibly, the sky lightened and the dirt road alongside their house began to grow visible. A dark shape clattered by. A few moments later, another passed.

She looked at her husband. “Maybe we had better go to the mesquite bushes and hide.”

He shook his head, telling her they had nothing to fear, that they had always treated their Mexican customers fairly.

Soon the road was filled with retreating Villistas. One group turned into the Moore’s yard and watered their horses at the tub of drip water. “Again I looked towards town and saw the road and open space covered with stumbling, wounded, dirty, ragged men. Some of these men were afoot, some on horseback, clinging desperately to the necks of their horses.”

An officer wearing a cape coat and sitting astride a white horse ordered several of his men to check out a neighbor’s home to the north of them. It was Candelario Cervantes and los namiquipenses—the men from Namiquipa. He nodded toward the Moore home. The soldiers climbed up onto their front porch. One used the butt of his rifle to break the glass on a bedroom window. Mr. Moore told his wife to go into the dining room. Then he went to the front door and opened it.

“Sabe usted dónde se puede haber escondido Ravel?”—“Do you know where Ravel is hiding?” Cervantes asked.

“No soy el guardián de Ravel,” John responded.

“Muy bien,” said Cervantes.

Then his soldiers fell upon John.

“They raised their hands and struck him. They raised their sabers and knives and stabbed and slashed him. They raised their guns and shot him,” said Susan.

The assailants crouched over John’s lifeless body, removed his ring and his watch, and went through his pockets. Suddenly they remembered Susan and started toward her.

“Pan? Oro?”—“Bread? Gold?” asked a soldier. She looked at him closely and realized he was none other than the man who had been in her store the previous day to buy the pantalones. The Mexicans grabbed her by either arm and gestured at her rings—a plain gold wedding band, a diamond solitaire engagement ring, and a monogram ring set with diamonds.

As she struggled to remove the jewelry, her thoughts were racing. She was certain that she would be killed just like her husband. “Then the thought came to me that I might surprise or outwit them. The next thought that came to me was to scream. I screamed twice, at the same time I looked towards Mr. Moore and the front of the house, to attract their attention away from me, and to give the impression that someone had come.” Her captors loosened their grip as they turned to see what she was looking at. Susan jerked free, picked up her skirts, and fled out the back door. Several soldiers were in the garage trying to start the Ford.

“Mira, mira, señora!”

They fired at her. She felt a stinging sensation in her right leg and knew that she had been shot, but kept running. A second bullet slammed into her right hip. She fell, but got up and continued. Running and falling, she eventually reached the barbed-wire fence that enclosed their immediate property. Somehow she managed to heave herself over the fence and she crawled toward a clump of mesquite.

As the gunfire grew intermittent and then stopped altogether, the sweet sound of morning rushed in. Susan Moore lost consciousness. When she awoke, she realized that she was bleeding profusely and tore a ruffle from her petticoat to bind her wounds. Then she passed out again. When she came to, she heard the sound of horsemen and realized it was the American soldiers. She hung her handkerchief on a bush and called out weakly to them.

Captain Smyser and two privates found her. “Why, it is a woman. My God, it is Mrs. Moore!” he shouted. “Are you hurt?”

In a calm voice, she responded, “Yes, Captain, I am shot, but I can wait, if you will go to the house and take Mr. Moore in. They have killed him and you will find him on the front step.”

Soon other soldiers arrived. They pulled off their coats and made a bed for her. Someone gave her brandy. Another brought her water in a milk pan. A third shielded her face from the sun. As they were tending her, she noticed a dirty young American woman standing nearby. It was Maud Wright.

“She was dressed in a coarse linen dress with a little Dutch bonnet and was very, very dirty. However, I was glad to see a woman, especially an American, and she came up to me and said she had been a prisoner of Villa for nine days. I looked at her, she looked like she was hungry to me, I asked her if she had had any breakfast, she said no, I told her when we got to town to go to any of these restaurants and get whatever she wanted and have it charged to me, and I asked her to stay with me, and go to town with me in the ambulance, which she did.”

Together, Susan Moore and Maud Wright rode into Columbus. By then it was about ten o’clock in the morning. The sky was hard as enamel and the morning sun felt like shards of glass in their eyes. Susan lifted herself up and saw the smoldering remains of the hotel, the half-burned automobile that belonged to Charles DeWitt Miller, the bodies of horses and soldiers. She lay back down and closed her eyes.

There were other survivors. Milton James’s stepsister, Myrtle Wright Lassiter, lay unconscious near the Hoover Hotel with a head injury and bullet wounds in her thigh and right hip. She was picked up later that morning and taken back to Milton’s house, where she would eventually regain consciousness. Milton himself had managed to crawl to the east side of the hotel, where a man named Gardner picked him up and carried him down to the railroad tracks. Gently he laid Milton down on the embankment and then continued on his way. Later that morning, the train conductor, John Lundy, spotted Milton as the train began inching its way into Columbus. He was delirious and begging for water. Lundy lifted Milton onto the train and transported him to the army hospital. One of the bullets had passed through his penis and scrotum and into his right leg. A second bullet had slammed into his left leg, carrying with it bits of his clothing that were driven deep into the wound. But he would live.

As the sounds of the battle receded, the people of Columbus crept from their hiding places. The children ran ahead, excitedly fingering bullet holes in the thick adobe walls and grabbing up swords and guns. The Hoover Hotel served as a temporary hospital, the bank as a temporary morgue. In all, eighteen U.S. civilians and soldiers had been killed and ten others wounded.

FROM THE KNOLL south of the railroad tracks, Colonel Slocum and the other officers of the Thirteenth Cavalry had watched the dissolving shapes of the horsemen. Behind them Columbus still burned. Major Frank Tompkins had asked for permission to chase the attackers. Slocum had nodded, and in a few minutes thirty-two men were mounted and moving.

As Tompkins and his men galloped south, they could see the fleeing Villistas off to their right. They tried to catch up to them but their progress was greatly hampered by barbed-wire fences. As the Villistas retreated through a twenty-foot gap in the boundary fence, Lieutenant Clarence Benson and his men, who had been sent out the night before to patrol the border, killed eighteen fleeing Mexicans. Also killed at this point was Harry Wiswell, a thirty-eight-year-old corporal from Long Island, who just two weeks earlier had remarked upon the hostile attitudes of the Mexicans in a letter to his mother.

Upon crossing the international line, Tompkins spotted a low hill that was occupied by a rear guard of Villistas who had been left behind to cover the retreating troops. He ordered his soldiers to draw their pistols. “Charge!” he bellowed. The horses galloped up the hill. The Mexicans fired on them but their bullets went high and the Villistas broke and retreated just as the cavalrymen reached the lower slopes. When the troopers gained the top of the hill, they dismounted and trained their Springfields on the Mexicans. Their aim was far more accurate and dozens of Villistas and horses fell to the ground.

Realizing that they were now in Mexico and had violated standing orders from the War Department, Tompkins dashed out a note to Colonel Slocum asking for permission to continue the chase. In forty-five minutes, a messenger galloped back with an ambiguous answer: Use your own judgment.

Deployed at wide intervals, moving at a fast trot, the Americans charged the Villistas three more times. Each time, the rear guard of Villistas returned the fire and then continued their southerly flight. Eventually the U.S. soldiers found themselves on an open plain that was devoid of cover. The main body of Mexicans saw now that they outnumbered the cavalrymen by ten to one and prepared to counterattack. Tompkins and his men fell back about four hundred yards and waited, but Villa’s men, it seemed, were too exhausted to launch another offensive. Tompkins debated whether to continue the pursuit, but his troopers were almost out of ammunition and the horses were badly in need of water so he decided to return to Columbus.

They arrived back in town about one o’clock in the afternoon. In all, they had traveled between five and fifteen miles into Mexico and had made four stands. The chase had been deeply satisfying; Tompkins’s official report would claim seventy-five to one hundred Villistas had been killed during the pursuit. The number is probably exaggerated but points to a vexing aspect of the raid: the reported number of dead Villistas varied wildly. In Slocum’s official report, he stated that a total of sixty-seven Villistas were killed in the town, the military camp, or in the desert leading to the international line, and later upped the figure to seventy-eight. Whatever the number, there was no dispute that those charged with protecting Columbus had failed.

IN THE RUNNING gun battle back to Mexico, the Villistas dropped their loot, littering the desert with jars of chewing gum and cigars; spurs and bridles and saddles; wedding rings and gem-studded brooches; shoes and socks and underwear; tablecloths, sheets, and pillowcases, which caught on the sharp thorns of mesquite bushes and billowed gently in the dawn air. The Mexicans toppled from their horses into the brush. Most of them died, not as Villa would have hoped—as gladiators with their faces to the sun—but facedown in the sand, their mouths filled with vomit and soft pitiful moans that rose into the air and were carried off with the heat of the new day. Among the dead were two boys, both no older than fourteen. One was holding several pounds of candy, the other a pair of girls’ black patent-leather slippers.

At Arroyo del Gato, roughly sixteen or seventeen miles south of Columbus, the Villistas stopped and unsaddled their horses for a two-hour rest. Pablo López was suffering greatly from his wounds and so was a colonel named Cruz Chávez, who had been shot in the abdomen. The two officers were placed on stretchers and cargadores assigned to carry them. Nicolás Fernández gave Villa the sad news: sixty men were missing and unaccounted for, eleven of whom were his beloved Dorados. In addition, twenty-six were wounded, including López and Chávez.

Villa regarded Chávez mournfully. Then he turned to Candelario Cervantes and said, “It has come to this, Cervantes. I gave way to please all of you.” Cervantes, in turn, lashed out at Nicolás Fernández, saying it was Fernández who kept reassuring everybody that the attack would be successful. Martín López shook his head in disgust, adding that it had been a “futile effort for a few dollars.”