By far the biggest capital market centred on London is the euromarket or the international market. The two terms do not mean exactly the same thing, but we will come to the differences later. You do not read a great deal about these markets day-to-day – except in the Financial Times and a few specialist publications – because they are markets for professionals, they have no central marketplace and they have not in the past directly impinged on many private investors in Britain. Yet, in terms of money raised, they completely dwarf Britain’s domestic markets.

Moreover, now that inflation is under better control than in recent decades, both companies and investors are far more alive to the attractions of bonds, which are the mainstay of the international market. Add to this the explosion in takeover activity among very large companies, much of which is being financed by debt issues, and it should come as no surprise that activity in the euromarket has soared in recent years. The only fly in the ointment as far as Britain is concerned is the European Union’s attempt to impose a withholding tax on savings, which could seriously damage the country’s position as the centre of euromarket activity. This ongoing row surfaces frequently in the press: more of this later.

To understand the euromarket, start by thinking how markets evolve. A group of people have a need to come together to barter or sell goods. The market grows initially out of this need. It is probably informal, and some markets remain that way. But after a time – and particularly in financial markets – the participants may decide to introduce a more formal structure and a set of rules. It could help the market to function more effectively. It could reduce sharp practice and increase public confidence in the market. It could also, of course, allow the original participants to frame the rules so as to keep others out and to ensure that the market provides them with a good living.

At a later stage, governments may take a hand. Activity in financial markets can have far-reaching economic implications. The government may feel it needs to exert a measure of control. It may decide the market needs supervising by a governmental body. And so on.

Thus, most countries have domestic financial markets that are more or less closely regulated – directly or indirectly – by their respective governments. As we have noted, the trend in recent years has been to dismantle a great deal of this regulation – the deregulation process – and to throw domestic markets more open to competition. But this has not always been the case. And, when financiers have perceived a need or an opportunity that could not be exploited in the existing regulated markets, they have often tried to find a way round the problem, perhaps by operating in a new ‘black’ market of their own. The euromarkets have their origin in this sort of process.

The conventional explanation of the euromarkets used to be that they were an informal market in money held outside its country of origin. Thus, deposits of dollars in a European bank would be eurodollars, deposits of German marks in a British bank would be euromarks, and so on. This money could be borrowed and lent without going through the domestic financial markets of the country concerned and this is what, in fact, happened. Initially, much of the business was in dollars, hence the term eurodollar market in the early days.

Nowadays, when people talk about the euromarket they are referring not so much to the origin of the money that is borrowed and lent but more to the structure and techniques of the market in which it is traded. And the ‘euro’ part of the title is also misleading: the market is a market between banks worldwide. It is by no means confined to currencies held in European banks, or to European currencies. Nor does its origin have anything to do with the new European currency: the euro. There are euroyen and a ‘euro’ version of the Canadian dollar, and have been since long before such a currency as the euro existed. The market did, however, have its origins in Europe and more specifically in London, which remains the main centre – a factor that explains the presence of so many foreign banks. If we are drawing a distinction between the euromarket and the international market, we would probably say that the former covers transactions in the currencies of which there is a recognized ‘euro’ version and the latter term would also embrace dealing outside domestic markets in money or securities denominated in any currency. In practice, the two terms are often used virtually interchangeably.

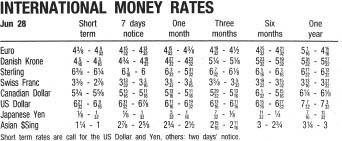

Example 17.1 Rates for borrowing and lending in different currencies in the international market. Source: Financial Times.

The important point is that the international market does not belong to any one country, nor is the market as such regulated by any country’s domestic supervisors (though London dealers in the market would come within the UK’s regulatory structure). Dealing in this international market is not circumscribed by the local rules and regulations of a particular financial centre. To this extent it remains ‘informal’ or ‘unofficial’, though market organizations have agreed some rules of their own. If London is the centre of the international market, the market is by no means run mainly by British institutions, nor are British companies among the most important users of the market. American banks and their offshoots are dominant, and to a lesser extent the Japanese.

Restrictions on capital-raising by foreigners in the United States domestic markets in the 1960s help to explain the establishment and growth of the international market in London, conveniently situated in the time zones. America imposed limits on the rates of interest that could be paid in its domestic markets and had levied a tax on foreign borrowers which made raising capital in New York uneconomic for them. London, on the other hand, offered a relaxed taxation and regulatory regime as far as the operations of the international market were concerned.

Nowadays, the international market mirrors most of the facilities and forms of security available in domestic markets. Eurocurrencies can be deposited and borrowed for very short periods or for many years. Borrowers can take out the equivalent of a term loan in a eurocurrency. They can issue various forms of bond or ‘IOU note’ to raise money in a eurocurrency. And because the eurocurrency market is largely unfettered by national restrictions, many of the more innovative forms of financing are first devised in the eurocurrency market and often copied subsequently in domestic financial markets. It is a case of giving the market what it wants or selling the market what you think it will take. Recent years have also seen considerable growth in euro-equity issues – issues of company shares via the international market rather than in the domestic stockmarket of the company concerned.

It is important to note the difference between borrowing a eurocurrency and simply borrowing in an overseas financial market. A euroyen loan is a borrowing denominated in yen through the international market structure whereas a samurai bond is a yen bond issued by a foreigner in the Japanese domestic market. A yankee bond is a dollar bond issued by a foreigner in the United States domestic market and a bulldog bond is a sterling bond issued in Britain by a foreigner. The samurai, yankee and bulldog are not eurobonds.

Out of the original short-term market in eurocurrency deposits – the inter-bank market - grew the syndicated loan market. Syndicates of banks would get together under a lead bank or lead banks to provide medium-term or long-term loans running into hundreds of millions or billions of dollars – though the currency in which the money was borrowed would not necessarily be dollars. It could equally well have been Japanese yen. By each contributing part of the loan, the individual banks avoided too large a commitment to any one customer.

Securitization of eurocurrency lending was the next step and the eurobond emerged. It is much like the bonds that governments and companies issue in their domestic markets (see Chapter 13), but the documentation and the issue techniques are somewhat different. It is also denominated in one of the eurocurrencies.

There are other differences, too. In Europe most domestic bonds suffer withholding tax. In other words, some income tax is deducted before the investor gets his interest. Eurobond interest is normally paid gross, without any withholding tax. The bonds are also issued in bearer form, rather than the registered form applying to UK domestic bonds, which gives them attractions for investors who do not intend being over-frank with the tax man (the tax advantages of eurobonds were probably a significant factor in the growth of the market). This is why Britain has been fighting to prevent the proposed EU withholding tax on savings and investments from applying to eurobonds. There is a very real risk that a significant part of the market’s activity might transfer to a more tax-favourable climate.

Another difference between the euromarket and the UK domestic market: the interest is normally paid once a year rather than in two half-yearly instalments, as is normal for UK domestic bonds. This means that a coupon of 10 per cent on a eurobond is not generally the same thing as a coupon of 10 per cent on a UK domestic bond. With the UK bond the investor can reinvest the interest he receives after six months and earn interest on it for the second half of the year. It means that 10 per cent paid in two instalments is worth the same as 10.25 per cent paid only once a year. Coupons and yields on eurobonds therefore have to be adjusted to express them in the same terms as returns in the domestic market. So you may read of a yield ‘equivalent to such-and-such an amount on a semi-annual basis’.

Issue techniques in the eurobond market are complex, and the way they work in practice is often somewhat different from the theory. At the two ends of the transaction you have the company or organization that wants to raise money via a eurobond issue (and needs to be sure of getting its money) and the end-investor in the bond (perhaps the proverbial Belgian dentist usually portrayed as the typical eurobond investor). Between is an array of banks. A lead bank (or group of banks) puts the issue together and agrees with the company the terms on which it will get its money. These banks need a good distribution network to be able to place a significant proportion of the bonds with investors. Other banks are brought in to take part of the risk of underwriting the issue (in theory, at least). Then there are other banks (the selling group) which are not part of the syndicate but which also use their extensive retail contacts to sell the bonds to the end-investors.

Once the eurobond has been issued in the primary market it can be traded in the secondary market, an over-the-counter or OTC market conducted by dealers over the telephone and television screen. In the early days the lead bank is allowed to stabilize (i.e. manipulate) the market in the issue by dealing itself. Whether or not it makes a profit on the issue depends on whether it can sell the bonds at a price that does not wipe out the fees it received. The secondary market can at times be a volatile market, partly because dealers (unlike marketmakers on the London Stock Exchange) have not had an obligation to make a market. If times got tough in a particular sector they might temporarily pull in their horns and the market would lose its liquidity.

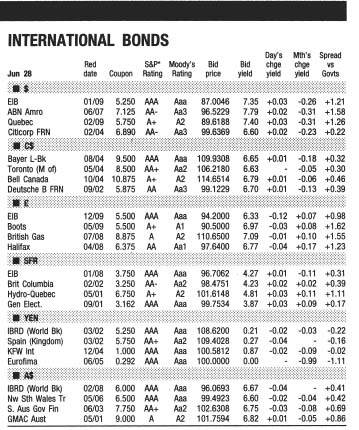

Example 17.2 A sample of bonds denominated in different currencies that are traded in the international market. Source: Financial Times.

Two organizations have provided clearance and settlement systems for international bonds and money-market instruments. These used to be Cedel in Luxembourg and Euroclear in Brussels though Cedel has recently merged with a German clearing house to form Clearstream and Euroclear has joined up with a French concern. The market’s self-regulatory organization – the International Securities Market Association or ISMA - is based in Switzerland but has an office in London.

The original straight eurobond carries a fixed rate of interest. But forms of bond were developed which pay floating-rate interest, known as floating rate notes (FRNs). Some banks have issued perpetual floating rate notes or perpetuals which are never required to be repaid, though the value of these suffered a dramatic market collapse in the 1980s.

The complexities arise in the many variations of these basic themes, introduced to make eurobonds more attractive to issuers or investors (or both). First the borrower must choose what currency he will borrow in; the interest rate would be usually lower in a traditionally strong currency (as the Swiss franc usually is) than it would be in sterling, but if the Swiss franc rises, the debt could be a lot more expensive to repay. Some bonds (dual currency bonds) reduce the currency exposure from the point of view of the investor: he puts up the money in one currency but is repaid in another at a rate of exchange fixed in advance.

Some eurobonds issued by companies incorporate an equity sweetener. Either the bond can be converted (wholly or in part) into the shares of the issuing company or it comes with warrants to subscribe for the company’s shares. The principles are the same as those outlined in Chapter 5 in the context of convertibles and warrants issued by domestic British companies. And, as in the domestic bond market, eurobonds may be issued at a deep discount instead of paying a rate of interest (zero-coupon bonds).

The real complexities, however, concern the interest rate and the compromises evolved to obtain some of the advantages of both fixed-rate and floating-rate bonds. Hybrid bonds are issued which pay a fixed coupon initially, followed by a floating rate after a certain date. Or there may be an upper limit (a cap) to the interest rate payable on a floating rate note (a capped floating rate note) and sometimes a lower limit or floor as well. There are even bonds which pay higher interest as interest rates generally go down. And the investor might have a put option or the issuer a call option, allowing one or the other to force early redemption in certain circumstances.

Even in the field of very short-term securities, there are counterparts in the international market to the instruments found in domestic financial markets. You used to read about the euronote: an IOU with a life of under a year. Borrowers would arrange with a bank or dealer to sell or take up the notes they issued under arrangements such as the revolving underwriting facility (RUF) or note issuance facility (NIF). The borrower could thus issue further notes as he needed the money or as the earlier ones fell due. Nowadays the emphasis is on eurocommercial paper (ECP) which works in much the same way as commercial paper in the domestic market (see Chapter 15). A somewhat longer-term version is the euro medium-term note or EMTN. An ECP programme may give the borrower the option of raising money in a range of currencies, and a number of British companies have used it.

Of late the distinctions between the domestic market and the euromarket in sterling-denominated bonds have been greatly eroded. Much the same firms deal in securities in both markets, and the rules for the issue of domestic sterling bonds on the London Stock Exchange have been relaxed to bring them closer in line with those applying in the euromarket. There have been sterling issues for UK companies divided between a ‘euro’ and a ‘domestic’ component, with the domestic part in the form of registered bonds. Many major British companies have issued convertible loan stocks and convertible preference shares in the euromarket, and for larger companies the choice between the two markets often depends mainly on questions of tax, issue costs and the type of investor they are trying to attract.

While the UK domestic market is the main one for the issue of secured loans (eurobonds are usually unsecured) the 1980s saw rapid expansion of euromarket issues of mortgage-backed securities by British-based specialist mortgage lenders who competed strongly with the building societies and banks to provide housing finance. Large numbers of individual residential mortgages – typically a thousand or so – would be ‘pooled’ in a special-purpose company which then issued floating rate notes or bonds to investors at large, thus recouping the money originally lent to homebuyers. The payments of interest and capital by these homebuyers provide for the interest on the notes and for their eventual repayment. The process is a prime example of securitization: mortgage loans are transmuted into tradable securities. However, mortgage-backed securities lost a fair bit of their appeal after the early 1990s collapse of house prices in Britain, though they are gaining in popularity again now.

The Financial Times carries a table of international money rates. These follow but do not necessarily exactly match domestic interest rates within the countries concerned. Rates are given for a range of eurocurrencies for deposits ranging from very short term to periods of up to a year. Needless to say, rates are lowest for the strongest currencies.

The key rate is three-month or six-month LIBOR, which stands for London inter-bank offered rate (see Chapter 15). This is the rate at which banks will lend in the inter-bank market, and is adopted as the benchmark rate of interest. The interest on floating rate notes is usually set by reference to the average rate of LIBOR and expressed as ‘so many basis points’ (hundredths of one percentage point) above LIBOR.

The distribution networks used by major eurobond dealers to market loan and bond issues to investors are used on a smaller (but growing) scale to market ordinary shares in major internationally known companies. It may suit a company to raise cash by selling shares outside its domestic capital market when this is too small for its needs. Other companies may wish to attract shareholders in overseas countries where they trade. Such operations are known as euroequity issues. British companies that are already listed are generally prevented by the pre-emption rules from using this route to raise further cash – new shares have to be offered first to existing holders.

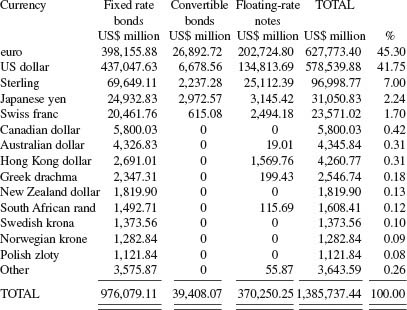

For an idea of the size and make-up of the international market in 1999, look at Tables 17.1 and 17.2, based on figures supplied by Capital DATA Bondware and Loanware. Our figures were drawn up a week or so before the end of 1999, and up to that point bond issues in the International market had raised the equivalent of some $1,386 billion in 1999 against some $929 billion for the whole of 1998, thus comfortably exceeding the $1 trillion mark for the first time. Apart from the rate of growth, the notable feature of 1999 was the emergence of the euro, in its first year of existence and despite its weakness in the forex markets, as the most popular currency overall in which eurobonds were denominated. The euro narrowly pushed the US dollar into second place. Loan facilities were arranged for some $468 billion. In addition, European equity issues (both primary and secondary) in the international market totalled $179 billion in 1999, again using the Capital DATA figures.

International market: money raised from bonds and loans

|

International |

Euromarket |

|

bonds |

loans |

|

(US$ million) |

(US$ million) |

1990 |

214,785 |

208,773 |

1991 |

285,835 |

149,395 |

1992 |

313,307 |

126,054 |

1993 |

441,238 |

148,703 |

1994 |

430,548 |

178,340 |

1995 |

464,284 |

323,650 |

1996 |

681,787 |

318,995 |

1997 |

749,032 |

364,462 |

1998 |

928,721 |

320,537 |

1999* |

1,380,865 |

467,821 |

* To 16/12/99

Source: Capital DATA Bondware and Capital DATA Loanware

Table 17.1

International bond issues in 1999 (to 22/12/99)

Source: Capital DATA Bondware and Capital DATA Loanware

Table 17.2

The form in which borrowers can most easily raise money is not always the form best suited to their purposes. Company A, say, finds it can easily raise fixed-interest money when it really needs floating-rate funds. Company B, on the other hand, has no problem in raising a floating-rate loan but its real need is for fixed-interest money which would be expensive for it.

The solution may be a swap - in this case an interest rate swap. Company A issues its fixed-interest bond and Company B issues a floating-rate loan. They then agree to swap their interest payment liabilities. Company A pays the floating-rate interest due on Company B’s loan and Company B pays the fixed rate of interest on the Company A borrowing, with some adjustment to reflect the relative strength of the two concerns. By this mechanism, each ends up with money in the form in which it needs it, at a cheaper rate than if it had borrowed what it needed direct.

This is the principle: each company borrows the money in the form in which it has the greatest relative advantage. The mechanisms are in reality more complex. Companies will not normally seek the counterparty for the swap direct, but will arrange a swap with a bank, which can either find a counter-party for the deal (taking a small cut in the middle) or may act as counter-party itself. And swaps, once set up, may subsequently be traded or adapted as conditions change in the market.

The second type of swap is the currency swap. Company A may be able to borrow on the most advantageous terms in German marks, because its credit rating is high in Germany where it is known. But it needs US dollars. Company B can most easily raise money in US dollars, but it needs German marks. So Company A issues a German mark loan and Company B borrows dollars. They then swap so that each ends up with what it needs, paying the interest on the currency it swaps into. Since each is borrowing where its credit is best, both end up with cheaper funds than if they had borrowed direct in the currency they needed. Again, a bank probably acts as intermediary. With many swaps both interest payments and currencies are exchanged.

It has been estimated that at times as much as 80 per cent of the funds raised in the euromarket are immediately swapped.

The interest rate paid by a borrower in the euromarket depends partly on the borrower’s standing. The main borrowers are governments, public bodies and internationally known companies, and companies known only in their domestic markets may be less well received.

Several organizations, including Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s and Fitch IBCA provide rating services which attempt to quantify the credit-worthiness of a borrower. The highest rating is AAA, hence the term triple-A-rated for the very safest borrowers. The same organizations provide ratings for short-term debt such as commercial paper.

Banks that are active in the euromarkets like to advertise their success in raising funds for clients. They do so partly by taking tombstone advertisements in the financial pages, particularly (in Britain) in the Financial Times and the magazine Euromoney. These advertisements announce that they appear ‘as a matter of record only’ (in other words they are not a solicitation to buy securities) and give the name of the borrower and brief details of the loan facility or bond issue arranged plus the names of the participating banks. The lead bank or banks which put the deal together appear at the head of the list and the remainder are normally listed in alphabetical order. The distinctive layout of these advertisements makes it clear why the term ‘tombstone’ is appropriate.

Domestic stockmarkets are usually hot on information and the press automatically receives details of most issues. The international market is rather different. The deals are between issuers and banks, rather than direct with the public, even though the public may end up owning the securities that are offered. There is no central stock exchange to impose disclosure rules. Details of a deal are frequently only publicized outside the market (see tombstones, above) well after it has taken place. Therefore, much of the information on what is happening in this mammoth market has to be picked up by specialist journalists with close contacts among the participating banks, who sniff out the rumours of a forthcoming deal.

The Financial Times publishes on a Monday a table of New international bond issues. On other working days its International capital markets page carries a smallish sample of international bonds denominated in different currencies, while its Euro markets page gives details of some major euro-zone bonds.

The monthly magazine Euromoney was set up specifically to cover the international capital market. Weekly news of new offerings, syndicated loan facilities and the rest appears in International Financing Review, aimed strictly at the financial community. And a variety of euromarket newsletters and news services such as the Syndicated Lending Review are also aimed principally at market professionals.

The clearing houses for international bonds are Clearstream (formerly Cedel) at www.clearstream.net/ and Euroclear at www.euroclear.com/. The trade and self-regulatory organization for dealers in international bonds is the International Securities Market Association (ISMA) whose London operation has a website at www.isma.co.uk/. The magazine Euromoney is at www.euromoney.com and Euromoney Publications’ associated company Capital DATA, which supplied the statistics for this chapter, is at www.capitaldata.com/. The three main rating agencies are Standard & Poor’s at www.standardandpoors.com/, Moody’s at www.moodys.com/ and Fitch IBCA at www.fitchibca.com/.