The public flotations of British Telecom, Trustee Savings Bank, British Gas, the water companies and the electricity companies attracted millions of first-time investors to the stockmarket. The flotation of former building societies such as Abbey National brought many more. But these issues could give a misleading impression of the way the bulk of the British public invests its money. Direct holdings of shares represent only a small proportion of the public’s savings. Most of it is tied up in a range of managed-savings products whose features and virtues are examined and discussed at great length in the personal finances pages of the national press, in specialist personal finance magazines and on a variety of personal finance websites on the Internet.

Personal-finance advice homes in on questions of performance, security and tax efficiency, with much attention devoted to tax shelters such as Individual Savings Accounts or ISAs (we will come to these later). So the advice you get from the press and elsewhere is likely to include the following elements:

• Start buying your own house as soon as you are able to do so. The interest payments on your mortgage are no longer tax-favoured as they were in the past. But capital gains on the sale of your main home are still tax-free.

• Make adequate life-assurance arrangements, both as protection for your family and as a means of saving. Here, too, former tax reliefs have gone, though there is partial relief on premiums for people with pre-1984 policies.

• Make sure you have adequate pension arrangements. Even if you are a member of an occupational pension scheme (a scheme run by your employer) there may be scope for making additional payments to secure additional benefits.

• Spare cash may be invested for safety and convenience with your bank or building society (and look carefully at the range of accounts on offer and the rates of interest that they pay).

• Only once you have taken care of the basics should you dip a toe in the stockmarket. And in the first instance this should be via some form of pooled investment vehicle where you have the benefit of a spread of risk and of (supposedly) professional investment management.

• Direct ownership of shares, in the traditional wisdom, is for those with enough spare cash to afford holdings in a spread of companies, thus reducing the risk if any one of them falls on hard times.

• Above all, take advantage of whatever tax shelters the government of the day offers. In the case of the previous Conservative government it was Personal Equity Plans (PEPs) and Tax Exempt Special Savings Accounts (TESSAs). With New Labour it is Individual Savings Accounts (ISAs). Various of the types of investment already mentioned may be held within the ISA tax shelter. Pension savings used to offer the best tax breaks of all, and still do to the extent that contributions (up to approved levels) are offsettable against income tax, while income and capital gains on the investments held in the pension fund are tax free. But the abolition of the reclaimable dividend tax credit under New Labour reduced the returns that pension funds can derive from their equity investments.

A quick glance at the investments and savings held by the British public mid-way through 1999 underlines the pattern suggested by the advice above (see Table 21.1).

Investments and savings held by the British public at mid-1999

|

£bn |

Equity in life assurance and pensions |

1,576 |

Sterling bank deposits |

367 |

Sterling building society deposits |

105 |

Quoted UK shares |

231 |

Unquoted UK shares |

214 |

UK mutual funds |

136 |

UK government bonds (gilts) |

31 |

Table 21.1

Savings via financial institutions (life assurance companies and pension funds) account for the vast bulk of the British public’s savings. Deposits with banks and building societies come next; bank deposits have grown and building society deposits declined as more building societies have transmuted into banks. Direct holdings of quoted UK shares come a very poor third. These direct holdings of shares have actually been rising in value terms in recent years because of a buoyant UK stockmarket in the later 1990s and the coming to market of previously mutual concerns such as building societies. But private individuals still regularly sell more shares than they buy each year. Indirect holdings of shares via mutual funds (essentially, unit trusts) are smaller still, though have grown a lot in recent years.

From these bare figures it is clear already that provision of personal finance services is big business. A walk down any high street suggests that Britain, once characterized as a nation of shopkeepers, has become a nation of money-lenders as bank and building society branches often outnumber conventional retailers. But this is only the tip of the iceberg. Less visible than the high-street deposit-takers and money-lenders is the vast fund-management business that makes its very comfortable living from the fees it charges for investing other people’s money. There are little more than 2,000 stockmarket-listed British companies that actually put money to work to earn a profit by providing goods or services. There are almost as many funds offering, for a fee, to invest the public’s money in the shares of these companies or, in some cases, their overseas counterparts. Have a look at the ‘Companies & Markets’ section of the Financial Times. London share prices occupy, at the time of writing, two pages. Listings of managed funds occupy seven pages, of which three relate to UK-regulated funds.

Much of the comment in the personal finance pages of the press concerns the relative performance of these managers of other people’s money. To see why performance – in terms of the overall return achieved – over a period of years is so important, just consider a few figures. If you invest £1,000 today at a compound annual rate of return of 6 per cent, in 40 years it would have grown to about £10,286. At a compound rate of 6.5 per cent it would have grown to £12,416. At 7 per cent, to £14,974. And so on. At 12 per cent it would have grown to the massive sum of £93,051. In other words, even quite a small difference in the annual return achieved can, over a long period, make an enormous difference to the outcome. These are the sort of sums that pension-fund managers, who may indeed be investing for 40 years, have to do. And they serve to emphasize the importance of tax in the investment figuring. If your £1,000 is compounding up at 6 per cent a year free of tax (as it could do in a tax-free pension fund), it will indeed be worth £10,286 after 40 years. If you have to pay 20 per cent tax on each year’s income, your net annual rate of return reduces to 4.8 per cent. At 4.8 per cent a year, £1,000 grows to only £6,523 after 40 years.

So we will need to look at tax shelters. But first the broad investment choices need to be put into context. With money left over after they have met their basic financial needs (life assurance, pension, etc.) savers may:

• make their own investment decisions direct (by buying shares in individual companies, buying government bonds, or whatever)

• put themselves in the hands of professional managers and achieve a spread of risk by buying into different kinds of pooled investment vehicle. But even here they have to make the choice of which manager or investment vehicle to select. There are, of course, managers who offer to select among the investment vehicles run by other managers. But even these managers of managers have to be selected!

Personal-finance advice in the press and the broadcast media concentrates very much on the pooled investment route. But remember that the performance of pooled investment vehicles depends ultimately on the performance of the underlying investments that they pick. Don’t rely too heavily on advice you read or hear from representatives of the fund-management industry. They make no money from people who decide not to invest, and even when the stockmarket is looking dangerously high they very rarely advise investors to hold off for the moment. Their usual argument is that, in the very long term, an investment will pay off even if it is bought close to the peak. It would, of course, pay off very much better if bought at a time when prices were more rational. For investors who are not confident that they can predict the peaks and troughs of the market, averaging is often a sensible policy. Invest a certain amount each quarter or each year. This way you will sometimes buy when the market is high, but these purchases should be offset by others that are made when the market is lower.

Whether investors choose direct stockmarket investment or the pooled funds route, they still have to decide on how to make best use of the tax shelter available. But choosing the tax shelter is not necessarily the same decision as choosing the underlying investments. First, what are the main savings products and from whom are they bought?

Much life assurance and related savings products is sold through financial intermediaries. In practice this often means insurance brokers who frequently (and often misleadingly) also operate under the title of investment advisers or financial consultants. These are one type of middle-man between the public and the insurance companies or savings institutions. Since most of them live from the commission on the products they sell, there is an inevitable temptation for them to be swayed in favour of the product paying the highest commission, and the independence of their advice is frequently called into question. Along with the insurance companies’ own sales forces, they have met considerable criticism over the mis-selling of personal pensions (see below).

As an indirect result of the City’s regulatory system, an increasing number of these financial intermediaries have in any case tied themselves to one particular insurance company or provider of investment products. Under a process known as polarization, investment product advisers have to decide whether they confine themselves to marketing the products of a particular group or whether they want to operate as Independent Financial Advisers or IFAs, marketing products from a range of providers. Nowadays the banks and building societies are also important middlemen in the savings market, selling their own or other people’s insurance and savings products. Professionals such as accountants and lawyers may also act as middlemen for savings products.

You will also come across the term discount brokers. These are vendors of investment products who, where the client does not require advice, may be prepared to remit to the buyer part of the commission that they earn on the sale.

The basic life assurance theme has an infinite number of variations. Term insurance is a straight bet with the insurance company: you pay premiums for an agreed period, and if you die during that time the insurance company pays the sum for which your life was insured. If you survive, you’ve lost the bet (or won it, depending on your outlook!) and you get nothing at the end of the period. Whole-life insurance pays a lump sum when you die, at any age. So your family gets something even if you live to 100.

Endowment asssurance is a savings vehicle for you as well as a protection for your dependants. You pay the premiums, and at the end of the term of the insurance you get a lump sum. If you die earlier, your dependants get a lump sum, as with whole life. The life assurance aspect of the contract is not too complicated: insurance company actuaries can calculate pretty accurately from mortality tables the risk of death before such-and-such an age (though new dangers such as AIDS cause problems) and provide for it in the premium they charge. The premium income goes into the life funds of the insurance company, where it is invested and this is where the main uncertainty arises: the return the insurance company will earn on its investments. In the case of a with-profits policy the policy-holder is entitled to a share of the profits from the growth of the fund.

Two points are worth noting on life assurance investment. First, returns on (particularly equity) investment may turn out to be considerably lower in the new century than they were in earlier boom days and the with-profits element for policyholders looks less attractive than in the past. This has worried people who bought life assurance to pay off their mortgage (see below). Second, many investors who enter into a life assurance contract subsequently find themselves unable to maintain their payments and need to take their money out early. What they receive – the surrender value – is usually very low in the early years compared with what they have paid in, partly because the salesman’s commission comes mainly out of the early payments (front-end loading). Insurance companies are now required to give prospective clients more information than in the past on commissions and costs.

Personal pensions are best viewed as being part of the same general business as life assurance, and the major insurance companies provide them. They also run a lot of company pension schemes for smaller and medium-sized groups. Take the company schemes first. These may be insured schemes, where the insurance group tells the company what premium it needs each year to provide the eventual level of benefit required for the employees. Or the company may hand over the contributions to be invested in a managed fund run by the insurance group; the pension scheme is allocated units in the fund pro rata with its contribution, and the value of the units depends on the investment performance of the fund. Or the pension fund may simply employ the insurance company as an investment manager, to manage its assets as a separate fund: a field in which merchant banks, brokers and other fund management groups also compete fiercely.

Alternatively, the pension fund can, of course, manage its own investments, as some of the larger ones do, or it can manage part of the funds itself and contract out management of the rest. With a buoyant stockmarket and high real returns on investment, many pension funds showed surpluses in the second half of the 1980s and the earlier 1990s. The value of their investments exceeded what was needed to meet expected liabilities. These surpluses were reduced in a number of ways – many companies took a contributions holiday – and were also being ‘raided’ by the sponsoring company and by takeover practitioners.

For much of the postwar period, employees of a company which ran its own pension scheme were normally forced to join that scheme. From 1988 they have been free to make their own arrangements, sometimes known as personal portable pensions because they can be taken from job to job. The self-employed already do this if they do not wish to rely on the fairly meagre benefits of the state pension schemes. To build up bigger pensions, those in occupational pension schemes may make additional voluntary contributions or AVCs.

Private-sector pension arrangements fall into two main types. Traditionally, company schemes have been mainly defined benefit (otherwise known as final salary) schemes. An employee builds up his entitlement each year he works for the company and, typically, might receive a pension of two-thirds of his final salary if he has worked for 40 years for the same company by the time he retires. The problem with this type of scheme for the sponsoring company is that it does not know in advance what the pension liabilities will be. This is because it does not know what salaries will be at retirement age or what investment returns will be earned on the contributions over 40 years.

This problem does not crop up with the other type of scheme: the defined contribution or money-purchase scheme. With these schemes a certain amount of money is contributed each year and invested. When the member retires, his ‘pot’ of accumulated money is used to buy an annuity to provide him with an income for the rest of his life. But the income does not necessarily bear any particular relationship to his salary in employment. Its size depends on the investment returns earned on his money over the years and the levels of investment yields at the time that the annuity must be bought. Personal portable pensions are of the money-purchase type.

For prospective pensioners in money-purchase schemes, the big fall in long-term bond yields that took place in the later 1990s has come as bad news. If money earns lower long-term returns – which is the effect of a fall in bond yields – then a given pot of money buys only a reduced income on retirement. Those in a company scheme with the promise of a pension linked to final salary are more fortunate.

Pensions have, in general, been under something of a cloud in recent years. The plundering of his company pensions schemes for many hundreds of millions of pounds by the late Robert Maxwell sent a shiver through the pensions business. And the mis-selling of personal pensions brought further unfavourable publicity for parts of the pensions industry (see Chapter 22). Pensions are an exceedingly complex area and it is often difficult if not impossible to get competent impartial advice. Walk with extreme care.

Buying a house with the help of a mortgage is usually regarded as a form of savings and mortgages, too, can have a life assurance element. The homebuyer can take out either a repayment mortgage or an endowment mortgage. With the repayment mortgage the amount borrowed is repaid via monthly instalments of interest and capital (more interest and less capital in the early stages and more capital and less interest in the later ones). Repayments are calculated so that the whole of the sum will have been repaid by the end of the term: usually 25 years though, because people move house, the average life of a mortgage in practice is much shorter. The interest rate on mortgages is traditionally variable, so payments have to be adjusted up and down as interest rates change. Changes in the rates are always hot news. But the shock of very high interest rates in the late 1980s and early 1990s encouraged many home-buyers to require (and mortgage-providers to supply) mortgages where the interest rate was fixed, at least for the first few years, or where there was a cap on the maximum interest that could be charged. Homebuyers taking out a mortgage need to check the fine print very carefully. Are there penalties for early repayment, for example?

The endowment mortgage introduced the life assurance. The money to buy the house was borrowed, usually from a building society or bank, and interest was paid to the lender in the normal way. But no capital was repaid. Instead, the borrower took out an endowment life assurance policy which, when it matured, was intended to provide a lump sum large enough to repay the loan from the building society or bank and – with any luck – provide a surplus on top. But in recent years there have been fears that these lump sums might not turn out to be large enough to repay the mortgage and the popularity of the endowment mortgage has evaporated. There is no doubt that many homebuyers were persuaded into endowment mortgages when a repayment mortgage would have been a better bet. You don’t need to look far for the reason. There was a commission to be earned from the sale of the endowment policy.

Move beyond the basic insurance and loan products, and you are next likely to meet the unit-linked investment vehicles, a form of pooled investment scheme. These give some of the benefits of stockmarket investment while spreading the risks.

It is inappropriate, as we have seen, for an individual with modest savings to risk them all on the vagaries of one share price –although we were asked to believe that this did not matter when the Government was off-loading previously nationalized industries. It makes sense for those with small amounts of capital or no knowledge of the stockmarket to invest in a spread of shares rather than the shares of a single company. Hence unit trusts and unit-linked assurance. Look at the pages of tables at the back of the Financial Times, before the stockmarket prices and at the beginning of the section headed FT managed funds service, with the main sub-headings authorized investment funds and insurances.

Despite the variety on offer, the principle of unitized, pooled or collective investment is simple. Suppose you and 99 other people each stump up £1 for investment in a new unit trust. The managers thus collect £100 in total and use it to buy shares in a variety of companies. Over a period the value of the trust’s investments rises by, say, 20 per cent. The original £100 of investments is now worth £120. You own one of the 100 units in issue, so the value of your unit is one hundredth of the total value of the fund. In other words, its value has risen from £1 to £1.20 (the actual calculations, allowing for costs, are of course more complex). How would you sell your unit if you wanted to cash in? You would sell it back to the managers of the unit trust, who will then try to sell it to somebody else. If they cannot do so, they may have to sell some of the trust’s investments to raise the money to pay you.

Unit-linked insurance incorporates a similar collective-investment mechanism, where the value of the unit is linked to the value of a specific fund or sub-fund of investments, but technically it is a life assurance contract. You hand over your money to the managers. A small proportion of it goes to provide a minimal amount of life assurance cover. The remainder is invested in units of what is technically a life fund. If the value of the fund rises, the value of your investment rises, too. What is the point of unit-linked insurance, when you can invest in unit trusts? In the past, there were tax advantages in investing in a life assurance contract. Also, a life fund could invest direct in property (unit-linked schemes invested in property are called property bonds) and the scheme could be sold door to door, which was not then allowed in the case of unit trusts. The treatment of the two types of investment is now closer in line and property-owning unit trusts are now permitted.

The operations of a unit trust are not, of course, quite as simple as in the example. There are charges for the service: typically, an initial charge of 5 per cent or 6 per cent of the value of your investment and an on-going annual charge of 1 per cent or more. Both initial and annual charges have risen over the years, notably the annual rate. And, as with shares, there is not a single price for the units. There is a buying price and a selling price: you buy the units from the managers at the higher ‘offer’ price and receive the lower ‘bid’ price when you sell them back. The price spread partially reflects the fact that the unit trust itself has to pay a higher price when it buys shares, gets a lower price when it sells them and will incur dealing expenses. If a unit trust suffers a large outflow of funds it has some leeway known as a bid basis or liquidation basis. Some unit trusts are now structured with no initial charge, but with an ‘exit’ charge diminishing over a period of years. A few may make an exit charge anyway when the investor sells within a given number of years.

Note that performance figures for unit trusts should always allow for the spread. So if the quotation for a particular trust has moved up from 100p–107p to 120p–128p over the year the calculation should allow for the fact that the investor would have bought at 107p and sold at 120p: a gain of 13p or 12.1 per cent, not 20p.

Open-ended investment companies or OEICs operate much like unit trusts, and some unit trusts have turned themselves into OEICs. But there are technical differences. OEICs are companies, not trusts, and they therefore issue shares, not units. But the share price is not determined by the interplay of buyers and sellers in the market. As with a unit trust, it is calculated from the value of the assets that the OEIC owns. Unlike a unit trust, however, the OEIC quotes a single price rather than a buying and selling price. Management charges are levied separately. The OEIC is open-ended (like a unit trust) because it can create further shares when required by investor demand. The OEIC was introduced because its operation may be simpler to understand than that of the unit trust and its structure conforms more closely with the structure of mutual funds in the rest of Europe.

A unit trust which is marketed to the public needed in the past to be authorized by the Department of Trade and Industry, though responsibility for authorization has passed to the Financial Services Authority. There are also unauthorized trusts which some stockbrokers run for their clients or which may be located offshore. Advertisements for unit trusts are fairly closely monitored and must contain a health warning – a reminder that the unit price can go down as well as up.

When they first launch, unit trusts may make a fixed price offer for a limited period – you will see the advertisements in the financial pages of the national papers, usually on a Saturday or Sunday. At this time you can apply for units at a known price. The rest of the time you normally pay the price ruling around the time your application is received. Fund management groups also frequently provide the opportunity for regular savings plans: you arrange to pay so much a month, the money being invested in units when it is received.

Unit trusts must pay out the income they receive on their investments to their unitholders, pro rata with their holdings. But sometimes the investor has a choice between income units (where he receives his share of the dividends in cash) and accumulation units (where his share of the income is added to the value of each unit). This second option is a convenience but does not offer any tax saving: the income is reinvested net of basic rate tax and any higher rate tax due has to be paid. However, accumulation units are not charged with the cost of reinvestment and the investor also has a better record of his total return when he keeps the same number of units. An alternative is for the investor to be credited with additional units representing the reinvested net income. This may involve paying preliminary charges on the new units.

The Financial Times lists over 150 fund-management groups offering authorized unit trusts or OEICs and not far short of 100 offering unit-linked assurance. Variations of the same name frequently crop up in both categories: most of the larger fund management groups offer the whole range of unit-linked products.

Computers make it easy to calculate the value of a trust’s investments each day, and hence the unit price. The Financial Times listings show, for unit trusts, both the lower bid price (price at which an investor may sell) and the higher offer price (price at which an investor may buy) and the price movement over the previous day, plus the yield. In many cases separate prices are shown for income units and accumulation units: the latter will be higher, because of the reinvested income.

The original idea of unit trusts was to offer a spread of investments across most areas of the stockmarket. Then came more specialist funds, investing according to particular philosophies or in particular areas. Have a look at the trusts run by the major management groups. There will probably be a general fund. Then there may be funds investing for high income, in smaller companies, in recovery stocks (companies down on their luck whose share price should improve dramatically if they pull round) in technology stocks, and so on. There may be unit trusts investing only in investment trust shares. And there is probably a tracker fund, simply seeking to mirror the performance of a particular stockmarket index. There will also be trusts investing in specific geographical areas or types of market: America, Australasia, Japan and Europe, emerging markets and the rest. There are also unit trusts which do not invest in shares at all but invest in the money market or in government or company bonds.

A similar range of investment policies is evident in the unit-linked assurance funds, normally known as bonds (though not to be confused with government or company bonds). In fact, many unit trusts have a bondized equivalent: an insurance fund that invests in the relevant unit trust. The prices for the bonds, under the heading of insurances, follow the same pattern as those for unit trusts, except that no yield is shown since no income is distributed. With unit-linked assurance, the income from the fund’s investments is automatically reinvested in the fund after deduction of tax at the life assurance rate. A life fund is also taxed on capital gains (unlike unit trust funds, which are exempt from gains tax) and this is reflected in the price of units.

After the insurances in the Financial Times come the prices for offshore and overseas funds. These are not authorized unit trusts, though they operate on the unit principle and many operate under the umbrella of one of the fund management groups that offers authorized unit trusts in the UK. Many of the offshore funds are technically located in the Channel Islands and managed from there, the UK parent group being described as ‘adviser’ to the fund. Hence management group names with ‘C.I.’ in the title.

The offshore funds operate under the tax regime of the country where they are located: usually more liberal than in Britain. But for a British investor living in Britain there is no tax advantage in investing in them. He will be treated for tax according to the UK rules. Expatriate Britons working, say, in the Middle East and paying little if any UK tax may do better in an offshore fund than in one registered in the UK.

Performance statistics for unit trusts and bonds are closely followed. The monthly magazine Money Management provides a comprehensive list showing the value of £1,000 invested over periods ranging from six months to seven or ten years, and various Internet websites also provide performance information (see end of this chapter). Performance can vary very markedly, particularly over the shorter periods, and for the intrinsically more speculative funds invested in foreign markets, picking the right country is often more important for the managers than picking the right share, especially at times of wild currency swings. Needless to say, around the turn of the millennium, trusts specializing in technology companies had done particularly well over the previous year. The problem is that an investment policy that was precisely right one year, in terms of market sector or geographical area, could equally well be precisely wrong the next. More cautious investors will look for consistent outperformance over longer periods as evidence of management quality.

In fact, unit trust investors should be aware that many trusts are marketing-led rather than investment-led. The managers find it easy to market a new trust investing in an area that has recently become fashionable and attracted widespread press comment. But by the time the trust is launched, the best of the growth may be past. For investors the trick is, as always, to get into the areas that will become fashionable before they have done so. Likewise, unit trust sales and the volume of unit trust marketing tend to rise when the stockmarket has been on a rising trend for a long time and everybody has noticed the profits being made. In practice, the market may be near its peak and it could be the worst possible time to buy. Cynical unit trust investors tend to invest counter-cyclically. They may buy the previous year’s worst-performing trust on the basis that its policy could turn out right the next year – and buy unit trusts in general when the market is low and marketing hype is minimal.

There is one other – and much older – form of collective investment vehicle that crops up frequently in the personal finance pages: the investment trust. An investment trust is a company whose business – rather than making widgets or running laundries – is simply to invest in other companies. It holds a portfolio of investments in the same way as a unit trust or a life fund, thus providing professional management and a spread of risk. But you cannot buy ‘units’ in an investment trust. You buy its shares, in the same way as you would buy the shares of an industrial company. Investment trust share prices are thus listed in the share price pages of the Financial Times rather than on the unit trust or insurance fund pages.

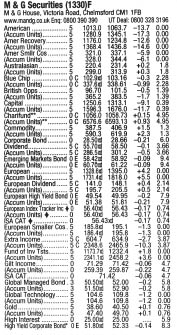

Example 21.1 Some of the unit trusts offered by one of the UK’s major fund management groups. Source: Financial Times.

The value of shares in an investment trust is determined in exactly the same way as the value of the shares in any other company, by the balance of buyers and sellers in the stockmarket. But in making their buying and selling decisions, investors naturally look at the value of the investments the trust owns, usually expressed as a net asset value per share, or NAV (see Chapter 4) and for technical reasons the share price of an investment trust nowadays is normally below the value of the assets backing the shares. In other words, it stands at a discount to the NAV. The size of the typical discount varies with stockmarket conditions.

This poses a considerable problem for anyone wanting to launch a new investment trust. Say he proposed to offer 100 shares to the public at £1 each and invest the £100 he received across a range of companies. The investment trust would have a portfolio of investments worth £100 and the NAV of each of its own shares would thus be £1. But the chances are that the shares would trade in the stockmarket at less than £1: say, at only 80p (a discount of 20 per cent to the NAV). Few investors want to put up £1 for something which shortly afterwards will be worth less.

There are various ways an investment trust can try to reduce or eliminate the discount to the asset value. It may offer special investment expertise in a particular area, which encourages investors to rate its shares more highly, or may attempt to cash in on a current stockmarket fashion. It might have considerable gearing – investment trusts can use borrowed money as well as shareholders’ money – which means the asset backing for the shares would rise faster than the value of the investment portfolio in a rising market. Or it might organize itself as a split-level trust. The principle is that the investment trust’s own share capital consists of income shares and capital shares, the income shares being entitled to all the income from its investment portfolio and the capital shares being entitled to the whole of the rise in capital value of the portfolio over the life of the company, which is limited to a specific period. There are a number of variations on this theme, some of them considerably more complex and involving the issue of several classes of capital. In one version the trust also issues zero-dividend preference shares. Except for the fact that these are share capital rather than debt, they work rather like zero-coupon bonds (see Chapter 13). They pay no income, but are eventually redeemed at a premium, which therefore provides the equivalent of an annual rate of return over their life. The idea of these complex capital structures is that, by tailoring different securities to the needs of different investors, their value will be enhanced and the sum of the parts will be worth more than the whole would be if marketed as a single entity. Thus the discount problem can be alleviated.

But the surest way for an existing investment trust to increase its total worth is to be taken over or to unitize itself. Unitization simply means that the investment trust turns itself into a unit trust, substituting units for shares. The unit price is then calculated directly from the value of its investments (and fully reflects this value, which the share price did not). An investment trust is a close-ended investment vehicle, because it has a finite share capital. A unit trust is open-ended because the managers can create new units or cancel existing ones as demand and supply dictate.

However you choose to invest your money, you also have to think how you can best shield your savings from the taxman. Under the Conservative government there were two main forms of tax shelter available: Personal Equity Plans or PEPs (for holding shares or pooled investments) and Tax Exempt Special Savings Accounts or TESSAs (for holding money on deposit). Up to the stipulated limits, investments held within these shelters would be exempt from income tax and capital gains tax. The New Labour government has abolished these shelters for the future (though existing PEPs and Tessas may continue) and put in their place an even more complex tax shelter called the Individual Savings Account or ISA, which also protects from income tax and capital gains tax.

You read and hear a great deal about ‘buying’ an ISA, as if an ISA in itself were an investment vehicle. It isn’t. It is merely a form of wrapper in which your investments may be held. Unfortunately, you have to acquire this wrapper from an established financial organization and it is usually marketed complete with its content of investments. So in this sense you are ‘buying’ the wrapper and the contents at the same time. There are also what are known as self-select ISAs where you pay for the wrapper and decide yourself what shares you want to put into it, but these are rarer.

ISAs can be used to shelter a range of investments from tax, up to an overall limit of (in 2000-01) £7,000 a year. The three main categories are:

• cash (bank and building society accounts, and similar forms of deposit)

• shares and bonds (or pooled investments like unit trusts and investment trust shares)

• life insurance policies (or those designed for use in ISAs).

But to complicate matters there are two different types of ISA: mini ISAs and maxi ISAs. In any single tax year you have to opt for one type or the other. You cannot have both. But you may have up to three mini ISAs each year (one for cash, one for shares and one for life assurance) and you could ‘buy’ each from a different manager. You may have only one maxi ISA per year, into which you can put the same range of investments but the proportions may be different. For the 2000-01 tax year, the rules were that you could put into a mini ISA a maximum of £3,000 cash, £3,000 in stocks and shares or pooled investments and £1,000 of life assurance (there would, of course, be a separate mini-ISA for each element). The total amount that could be sheltered was thus £7,000. This same £7,000 overall limit also applies to a maxi ISA, but the difference is that you could put the whole £7,000 into shares, pooled investments or bonds, though you could also split your £7,000 between shares, cash and insurance as with a mini ISA if you wanted to. These maximum limits were likely to reduce in future years. Investors wanting the maximum possible tax shelter for direct or indirect stockmarket investment would obviously tend to opt for a maxi ISA with the whole £7,000 in shares, pooled investments or bonds.

Apart from their complexity, ISAs are far from ideal. They do provide protection against income tax and capital gains, but are obviously of limited interest to those who are not liable to tax and unlikely to become liable in the future. You have to go through a stockbroker or financial institution and the initial and annual charges from the manager may soak up a fair bit of any tax benefit that you get. But it does still make sense for most investors to use an ISA to shelter as much as possible of their investments from tax each year. For more information on how ISAs work, and the residual arrangements applying to PEPs and TESSAs, ignore the marketing hype from the ISA vendors and look instead at the independent FSA guide to ISAs. You may download it free from the Financial Services Authority website at www.fsa.gov.uk.

How do you know if you are paying too much in charges when you buy investment products? This is a problem area because performance is often more important than the fees levied by the provider. An investment manager making an initial charge of 6 per cent but delivering 20 per cent growth will be a better bet than a manager who charges only 4 per cent but manages to achieve only 10 per cent growth. Unfortunately, there is no guarantee that higher charges mean better performance and managers prepared to be paid according to performance are conspicuous by their absence.

The government has tried to address this issue by introducing a CAT standard for certain financial products such as ISAs, pensions and mortgages. CAT stands for ‘charges’, ‘access’ and ‘terms’, and products which comply must meet fairly stringent conditions on all these points. You thus know that you are not being ripped off on charges if you buy a product that conforms to the CAT standard, but this does not necessarily mean that it is the best product for you or the one that will show the best return. Because of the limit on charges, the CAT-compliant version of a product is likely to be the most basic model, and another version which does not comply with the CAT standard might provide more of the features that you want.

Far more people buy personal finance products than would ever deal actively in the stockmarket. So this is where much of the money is for the financial services industry, which has not been slow to wake up to the opportunities offered by the Internet. Most of the larger providers of pensions, mortgages, unit trusts, ISAs, etc. have their own websites, which promote their products and vary considerably in quality. Many of the brokers who act as a selling conduit also maintain websites. But there are also a host of more independent sites providing both background information and latest price and interest-rate information on the whole range of savings products, often including performance comparisons. More detail on these personal finance sites is given in Chapter 23, but a good starting point is Moneyextra (which now incorporates Moneyworld) at www.moneyextra.com or Interactive Investor at www.iii.co.uk/. These sites cover the whole range of personal finance products and also provide educational and explanatory material, as do Moneyweb at www.moneyweb.co.uk/ and AAA Investment Guide at www.wisebuy.co.uk/. More detailed background information on unit trusts is obtainable from the Association of Unit Trusts and Investment Funds at www.investmentfunds.org.uk/ and on investment trusts from the Association of Investment Trust Companies at www.aitc.co.uk/. TrustNet at www.trustnet.co.uk/ provides performance information on pooled investment funds and two sites offering global funds performance information are Lipper at www.lipperweb.com/ and Micropal at www.micropal.com/. The Financial Services Authority site at www.fsa.gov.uk/ is worth a visit for the information it provides on some personal finance products, particularly ISAs, as well as for background on safeguards for investors and on the precautions they should observe.