If you had to characterize in a single word the financial developments of the last five years of the second millennium, the word would be ‘globalization’. Money is now truly international. And it is a global business not only for the banks and other financial institutions that have operated for a long time in an international marketplace. Globalization has now come down to the level of the individual investor who, with a home computer and an Internet connection, can track share prices in New York as easily as those in London.

The explosion in information technology goes way beyond providing information on markets and investment opportunities around the world. It provides new routes into these markets. At the turn of the millennium, Internet-based stockbrokers were less developed in Britain than in the United States. But already a fair number of firms offered facilities for investors to place their buy and sell orders on-line, and many more Internet-based brokerages were on the way. Internet-based banks, not necessarily domiciled in Britain, were already making a bid for the savings of the British public.

With the help of the Internet, consumers have far more opportunity than in the past to compare prices for products across a range of suppliers. This applies to financial products as to any other and is bad news for the rip-off merchants. In the long run it should help to even out unwarranted price differentials and reduce the scope for overcharging.

But the globalization of investment activity on the back of information technology brings its dangers as well as its benefits. Even as far back as 1987, the worldwide stockmarket crash demonstrated how rapidly a market panic could spread from one financial centre to the next (see Chapter 7b) as dealers’ screens showed instantly what was happening in other parts of the world. And the numerous currency crises of the past decade demonstrate clearly that no national economy can insulate itself from the global forces. The international currency speculators, with many billions of dollars at their disposal, are constantly waiting to place their bets on the rise or fall of a currency when signs of strength or weakness hold out the opportunity of a profit.

As when Britain was forced to drop out of the Exchange Rate Mechanism of the European Monetary System in September 1992, the speculators did not cause the weakness of sterling. But by selling pounds in vast quantities they greatly exacerbated it. The same process was at work when the speculators turned their attention to the currencies of the former ‘tiger economies’ – the high-growth countries of the Pacific Rim – in 1997 and helped to bring them low. In Britain, much of the emotional debate on whether or not to join the single European currency had tended to suggest that the country had independence in its economic management as long as it remained outside. In practice, decisions on interest rates and currency levels in Britain were greatly constrained by what other countries were doing, even while sterling remained nominally ‘independent’.

As well as these obvious effects of globalization, there are other risks in the information explosion. Not all of the information available is reliable or accurate. Nobody edits, censors or regulates the Internet and it is also often difficult to tell whether information on web pages is up to date. Organizations are keen to put the latest favourable information on their website. They are often less punctilious in removing outdated material. Always check to see if a document is dated. If not, be cautious in making use of it. Remember that organizations provide the information that they want to provide. Only too frequently this fails to include such items as the name of the organization providing the site, its physical address and other vital information needed to establish the bona fides of the site.

Websites are also a godsend to the public relations industry. An organization can project exactly the image it wants, displaying the flattering material and choosing not to display the less flattering items. The growth of websites has made it far easier for the public to access certain standardized types of information. Paradoxically, it may have made it more difficult to obtain answers to the more unusual one-off information requests. The growth of the web seems (with honourable exceptions) to have been accompanied by a very marked deterioration in the quality of more traditional information offices or press offices. If your query is not one that is covered by the standardized information on the website, it may be considerably more difficult nowadays to get hold of anyone who understands your question, let alone someone who is capable of giving the answer. This is the flip side of the mass information explosion.

There is also a more specific danger for investors to be found in Internet chat rooms, discussion groups and the like. The promoter of an overvalued or dud share may all too easily get his pals to post messages tipping the share as the greatest thing since sliced bread. It is worth remembering an old stock exchange adage ‘where’s there’s a tip there’s a tap’. In other words, those who tip shares frequently have a supply of them to offload.

Thus, there is some very valuable information for investors out there on the World Wide Web and there is also a lot of absolute rubbish. Moreover, the ability to trade shares via the Internet opens the way for practices such as ‘day trading’ – already established in the United States and seeking a foothold in Britain. This is the game of betting on short-term movements in share prices over the computer screen which – like any other form of gambling – may sometimes deliver big profits but is more likely to prove a recipe for disaster.

There is another risk posed by the information explosion that is more subtle and more insidious. In the profusion of information on the way share prices are moving, the way different indices are moving, the rates of return available on different forms of investment and so on, these figures take on a life of their own. Investment is thus reduced to a numbers game in which investors risk losing sight completely of the businesses on which these numbers are based. They rush to buy the latest self-styled technology stock because others are rushing to buy and thus the price is rising. But unless there is a viable business underlying the hype, this will eventually end in tears. That Internet-based bank may appear to offer a very competitive rate of interest. But who is behind it, what resources does it have, in what country is it regulated and what are the safeguards for depositors if something goes wrong?

The Internet may therefore have brought a revolution in the availability of information and in the methods of accessing the markets, but it has not changed the fundamental principles of investment or the questions that any sensible investor will ask. As in earlier editions, this book concentrates on explaining the principles and it explains them mainly in a British context. This is not to ignore the international aspect. The same principles are at work in markets across the globe, though practice will differ slightly in line with local conditions and traditions and it is not possible in a single book to cover every variation.

For the first time this book provides Internet sources of information and services that may be useful to the investor. This is not intended to be comprehensive, nor is there necessarily any judgement on the quality of a particular Internet site. Change is so rapid in the Internet world that judgements – particularly negative ones – could be quickly outdated. The sites referred to are among those that offer useful information for the investor and which may, indeed, have proved useful in updating this book for the new, fifth edition. The more important sites are shown both at the end of the chapter to which they are most relevant and as a list in Chapter 23 – Print and Internet: the financial pages – which also contains some additional websites. One particular point to note: in the past there was much information from government departments, financial institutions and companies that was available only to journalists or others with special access. Today, any member of the public with an Internet connection can access most of this information – press releases, background briefings, statistical information – from the relevant website. It is a valuable resource for anyone who wants to delve a little deeper into financial affairs and is one of the undoubted plus-points of the Internet revolution.

We have dealt with the Internet revolution first because it is the sexiest and the most dramatic development of recent years. But there have been other important changes since the previous edition of How to read the financial pages went to press in 1995.

At a domestic level, a New Labour government came into power in 1997 after a long period of Conservative rule. It inherited a healthy economy which it nurtured successfully at least into the new millennium, though the service sector fared considerably better than traditional manufacturing industry. In contrast to much of the postwar period, the strength rather than the weakness of sterling was an on-going worry, particularly for the manufacturing sector. One of the first acts of the new government had been to give independence to the Bank of England in the operation of monetary policy, which involved some careful balancing acts. By the turn of the century, a renewed house-price boom had erupted, at least in the south of the country. Higher interest rates may have been necessary to contain house-price inflation in the south. But since they would tend to support or increase the value of sterling, they were the last thing that manufacturing industry wanted.

The new government also made some important changes to the system of company taxation early in its period of office. Because these changes could be presented as technical in nature, they did not receive the degree of coverage or comment that they warranted. By phasing out the Advance Corporation Tax system, in effect the government increased the total burden of taxation on company profits by several billion pounds a year, mainly to the detriment of the pension funds. And by rescheduling and accelerating the payment of Corporation Tax by companies it also imposed a swingeing penalty on corporate cash flows.

Up to the new millennium, inflation in Britain remained under tight control, at least in contrast with the 1970s and 1980s. No longer did consumers expect large automatic price increases month by month, though experience varied between different categories of goods. Technological products, such as computers, were actually becoming cheaper by the month – not so much because prices were falling but because buyers were getting vastly more for the same money with each new model. Accompanying the lower inflation were much lower nominal interest rates than investors and consumers had been accustomed to in previous decades, though short-term rates – low by British standards – were still high compared with those applying in the euro zone. While this meant that borrowing costs were considerably lower than in the past in the UK, it also meant that savers earned a great deal less on their money. The much lower long-term interest rates meant that anyone buying a pension got a considerably smaller income than he would have got for the same money in the recent past.

Against this economic background, the UK stockmarket had put up a sparkling performance in the second half of the 1990s, only temporarily and modestly damaged towards the end of 1998 by problems in some of the emerging markets and particularly in Russia. Towards the end of the century it was pharmaceutical and technology stocks that were making the running and dragging the market indices ever higher. In consequence these indices did not always provide a rounded picture of the market as a whole. Towards the end of 1999 the London Stock Exchange introduced a new market-within-a-market for technology stocks. This techMARK came complete with its own indices for the technology sector. As the millennium approached, investors’ appetite for Internet-related companies reached fever pitch and market newcomers that had never made a profit were valued at many millions of pounds and saw their shares soar above the (often pretty optimistic) launch prices. Like most booms that get out of hand, this one showed all the signs of leading to future trouble.

The London Stock Exchange had vastly increased its dealing in overseas stocks in the 1990s and it also introduced a new trading system for the shares of larger British companies in 1997 (see Chapter 6). Meantime, shares held by major investors had been largely ‘dematerialized’. Ownership was recorded in electronic form and trades were settled via the new CREST electronic system, thus cutting out much of the paperwork and the need for new share certificates whenever shares changed hands. Private investors could, however, stick with the old paper-based system if they wanted to. But even greater changes were to come. Early in the new millennium the London Stock Exchange announced plans for a full merger with its German counterpart, to form a new grouping – iX or Integrated Exchanges – which might form the core of a truly pan-European exchange.

The regulatory system for financial products and financial markets in Britain was also undergoing a transformation at the millennium. A new ‘super regulator’, the Financial Services Authority, had taken over not only the regulatory powers of its predecessor, the Securities and Investments Board. It had also assumed regulatory responsibility for banks, building societies and various other financial entities.

The long period of economic prosperity leading up to the millennium was presenting commentators with an interesting problem, particularly in the United States – the powerhouse of world growth – but also in Britain. In the past, a period of economic growth had usually led to rising inflation and the need to damp down economic activity, giving rise to the familiar ‘stop-go’ economic cycle. This pattern seemed to have been broken in the 1990s when an unusually long period of growth appeared to have been achieved without seriously stoking the inflationary fires. Did this herald a new economic order, assisted by the productivity gains from the new technology, or had the inevitable downturn merely been deferred? In the United States the population as a whole had ceased to save, relying for its sense of prosperity on the value created by an ever-rising stockmarket. If the stockmarket fell, would this have a knock-on effect on the real economy by destroying the feel-good factor, discouraging spending and putting the brakes on economic growth? If so, the effects would be felt in Britain and across the rest of the world.

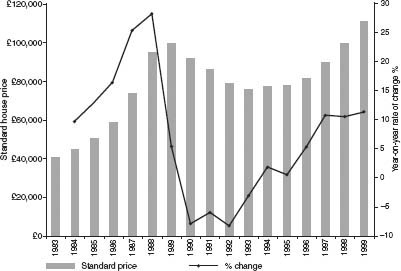

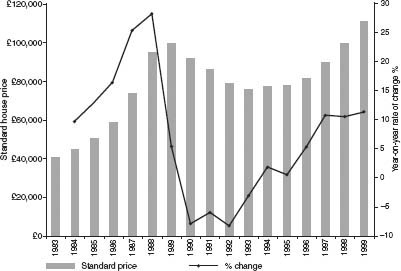

Figure Intro. 1 Standard house prices in South-East England The 1990s were the decade that shattered the illusion that house prices could move in only one direction: upwards. The price boom of the late 1980s was followed by sharp falls in value in the first half of the 1990s, leaving many recent buyers with the problems of ‘negative equity’ (owing more on the house than it was worth). But in the second half of the decade prices were moving rapidly upwards again in the affluent South East and by the millennium official interest rates were being raised partly in an attempt to head off a runaway house price boom. Source: Halifax plc.

In Europe the old century culminated with the introduction of a new single currency – the euro – in eleven member states of the European Union at the beginning of 1999. Britain stayed out of this ‘euro zone’, for the time being at least. The public debate on the merits and risks of joining the euro was conducted mainly at the usual ‘yah, boo and sucks’ level of British politics, disguising the fact that there were very real economic arguments for and against. In the foreign exchange markets the euro initially fared badly, losing over 16 per cent of its value against the dollar in its first year of trading. This weakness was cited by the anti-euro camp in Britain as a vindication of its stance. In reality, the economic cycle of the continental European countries was running behind that of the United States and Britain and the weakness of the currency was probably what European businesses needed in order to increase their competitiveness in world markets and assist the climb out of recession. The real tests for the euro were yet to come. But in one area the euro was highly successful from the outset. The international markets saw massive issues of bonds denominated in euros, reinforcing the argument that the new currency bloc would improve capital-raising efficiency for its members.

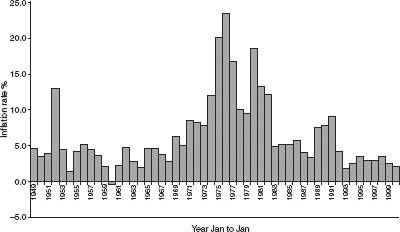

Figure Intro. 2 Retail Prices Index – annual percentage rate of change Has low inflation come to stay? By the millennium the British had come to expect only modest price rises year on year and some technology goods such as computers were becoming cheaper all the time. But this was far from being typical of the postwar experience. Ignoring a blip caused by the Korean war in 1951–52, inflation began to take off in the 1970s and peaked around 25 per cent. The runaway boom of the late 1980s led to a resurgence of inflation at the turn of the decade, before Britain began to move into quieter waters. Source: Office for National Statistics: Financial Statistics.

The end of the old century also saw a massive boom in takeover activity as businesses and industries regrouped, often across national borders, for the global marketplace. The world’s biggest-ever takeover offer at the time, the £77 billion hostile bid from British mobile-phone group Vodafone AirTouch for German company Mannesmann, emerged shortly before 1999 drew to a close.

The process of deregulation in financial markets and financial institutions, already established in the last couple of decades of the 20th century, continued into the third millennium. Banks were no longer restricted to providing banking facilities, building societies no longer merely provided home loans and insurance companies no longer simply sold insurance. The old barriers between different types of business were breaking down or had already broken down. If banks were not yet selling frozen peas, supermarkets were already providing a range of banking services and the process had further to go. Telephone- or Internet-based banking and insurance services were challenging (or being developed to supplement) the traditional institutions. In Britain, one of the major casualties of the new financial free-for-all was the building society movement, which had provided many generations of Britons with the loans to buy their homes. Many of these previously mutual organizations took advantage of their new freedoms either to launch on the stockmarket in their own right or to sell out to an existing bank. The incentive was the free shares or ‘windfall’ cash payments that existing borrowers and savers would receive plus – dare one say it? – the far greater salaries and other financial benefits that the managers would collect as directors of public companies. Building societies that tried to retain their mutual status were fighting a rearguard action.

Greater competition among suppliers of financial products brought benefits for the consumer in the form of more competitive rates of interest and the like. But it was not all gain. At the millennium many thousands of savers who had been persuaded to opt out of perfectly good occupational pension schemes in favour of overpriced personal pension products were still awaiting compensation for the loss they had suffered from dishonest or incompetent advice. And the profusion of financial products on offer brought its own problems. Shoppers were already familiar with the marketing line of conventional retailers: ‘find it cheaper elsewhere and we’ll refund the difference’. In practice, the product in the other shop was always slightly different in weight, composition or content, thus precluding direct comparisons. How much more difficult to judge between competing financial products, each of which had its individual features and quirks. Many suppliers in the financial sector were, regrettably, only too ready to exploit the opportunities of ‘confusion marketing’.

Alongside deregulation, the process of ‘disintermediation’ – cutting out the middleman – was also strongly at work in the financial sphere. Larger businesses that might have gone to a bank for a loan in the past were now as likely to raise the money direct from investors by issuing securities in a market. And banks were trying to replace the business they were losing by generating fee income from organizing or underwriting these securities issues in the markets. They were also doing massive business in devising and selling ‘derivative’ financial products. These are the products that businesses may use to protect themselves against movements in currencies and interest rates: in effect, often a sensible form of insurance. The other side of the coin is that these same products can be used speculatively to take massive bets on currency or interest rate movements. Britain’s oldest merchant bank, Barings, went belly-up early in 1995 as a result of massive losses from unsuccessful speculation in these products in the Far-Eastern markets. The remaining years of the century saw further sporadic examples of multi-million losses from operations with derivatives, both at banks and at their corporate clients. The knock-on effects of these individual cases were generally small, though more widespread trouble for the financial system as a whole was still frequently predicted.

Private investors are less directly concerned with the banks’ gambles in the financial markets and more directly concerned with the competing financial products and competing salesmen that daily scream for their attention. For them, the problem of finding sound, impartial advice grows ever more difficult. The pensions mis-selling scandal of ten years back was not, unfortunately, an isolated abuse. Until recently, many mortgage seekers were being persuaded into taking out endowment mortgages that were often wholly inappropriate to their circumstances but which, needless to say, paid juicy commissions to the vendors.

Lawyers, accountants, chartered surveyors and other professionals undergo many years of training before they are released on the public. Not so the myriad of financial salesmen and women whose commission-driven ‘advice’ may have even more serious repercussions on the wealth and comfort of their clients. In a sane world anyone putting the words ‘Financial adviser’ on a business card would be required to have at least a degree in financial management or a similar discipline. In practice, the words ‘Financial adviser’ should usually be translated simply as ‘Salesman’ or ‘Saleswoman’.

Given the shortage of sound, impartial advice, individuals are thus thrown back on their own resources. A useful technique before buying a financial product or a share is to test the assumptions underlying the price. What rate of return would the vendor of the savings product have to earn on your money to deliver the benefits he promises? If he seems to be assuming much too low a rate, you may not be getting value for money – too much of the return will go to him rather than you. If he seems to be assuming abnormally high returns, his promises may be suspect. And when you read a tip for an Internet-related company whose share price is soaring into the stratosphere, just work out on the back of an envelope what profits that company would need to earn to justify its market value. It may help to bring you down to earth, even if it takes a little longer for the shares themselves to submit to the forces of gravity.

Chief among the resources available to individuals is the information that they can gather from the financial pages of the newspapers, from the broadcast media and, today, from the Internet. But the information itself is of limited help without sufficient knowledge of the background to be able to understand it and put it to use. That is where How to read the financial pages sets out to help.