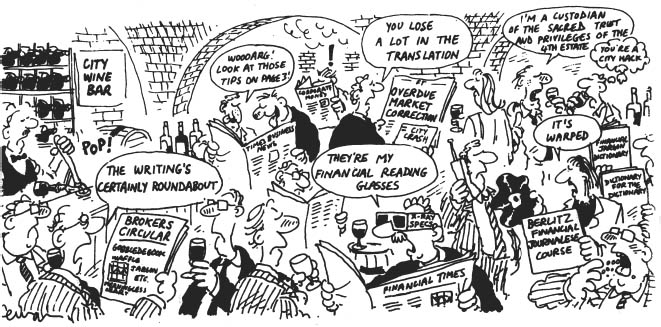

Reading the financial pages is one thing. Reading between the lines of the financial pages is a different art. Financial journalists do not always say exactly what they think – often because Britain’s very strict libel regime prevents them from doing so. Moreover, they are reporting on a world – the world of finance – that has its own layers of jargon and pseudo-scientific gobbledegook, often disguising the banal nature of what is going on.

To round off our examination of the financial markets, here’s a less serious guide to some of the more confusing turns of phrase you might come across in financial reports and the financial press. The interpretations are purely personal and in no way imply that the words and phrases are used in any particular paper or report in the sense suggested here.

The first problem the financial journalist hits is when he wants to put across a warning or express disbelief. Remember, we’re talking about money and a surprising number of people take money very seriously: particularly those who hope to make a lot of it or already have a lot of it to lose. Since this definition embraces a high proportion of people in the City, the journalist attacks them at his peril. A casual aside suggesting that the directors of Muggitt Finance put in a bulk order for rose-tinted spectacles before preparing their prospectus profit forecast is enough to have Muggitt’s lawyers baying at the gate.

In fact, can a journalist safely suggest that a share is vastly overpriced, even if he is not implying skulduggery on the part of the directors? It’s a moot point and he’ll often try to find a way round it. ‘Muggitt’s shares have fallen from 300p to 100p so far this year, and holders should consider taking their profits’ is one approach. If he simply thinks they’re far too high, without the company necessarily being on the skids, he might say ‘On a PE ratio of 35, Muggitt Finance is rated well above the sector average; this anomaly is likely to be ironed out in the near future’. He doesn’t mean that shares of the other companies in the sector are due for a rise. He means that Muggitt is heading for a fall. ‘With the PE ratio at 35, investors should not ignore Muggitt’s downside potential’ is another way of saying the same thing. ‘Not for widows and orphans’ simply means ‘highly speculative’ and occasionally ‘not for anyone in his right mind’. It is rather like the definition of a ‘recovery stock’. It can mean a share that is going to rise as the company recovers or a company that won’t be around very long if it doesn’t recover.

When a journalist suggests shares are ‘fully valued’ he is almost certainly trying to say ‘overvalued’ without offending the company too deeply. This is not the same thing as describing them as ‘fairly valued’, which probably means the writer hasn’t a clue one way or the other (‘a sound long-term hold’ also implies that he is sitting firmly on the fence).

There was a journalist in the pre-decimalization days who spoke his mind and suggested that one company’s shares ‘standing at 2s 6d’ were ‘about half-a-crown too high’. His fate is lost in the mists of history.

Comment on individuals is more perilous. For the financial journalist there can be no such thing as a crook, at least until he is safely convicted and behind bars (which, in Britain, he rarely is provided his crime is big enough). The paper’s lawyer might just let him get away with ‘controversial City financier’. Hence you’ll occasionally read pieces like this: ‘Speaking from Panama City, Mr Cyril Buck, the controversial financier at the head of the troubled Muggitt Finance group, today strongly criticized the decision by the company’s auditors to state that the accounts were prepared on a going concern basis and did not reflect a true and fair view of the company’s affairs’. In the vernacular this might be translated as ‘Cyril Buck, the spiv at the head of Muggitt, has done a bunk. He’s annoyed because the auditors say that the company is bust and the accounts are fiddled.’

Even journalism has had characters of questionable judgement, probably operating at the fringes of the share-tipping end of the market and almost certainly writing for a stockmarket ‘newsletter’ of the kind that claims divine insight into the future movement of share prices. Be a little careful when you read the following: ‘Since Rudyard Sharpe took the helm at the end of last year and injected his private business into Salter Way Holdings it is recognized as one of the most dynamic groups in the financial services sector. The shares are a narrow market, but should be bought at prices up to 200p’.

It may be a well researched and genuine tip. It could equally well mean: ‘Ruddy Sharpe flogged his private company to Salter Way at an exhorbitant price and is now ramping the shares for all he’s worth. That’s why he had me to lunch last week. The company’s a load of junk but there aren’t many shares around so the price will rocket if a few mugs jump in and buy them on my advice. That’s why I bought 20,000 myself at 140p last week. I’ll sell the moment my readers have pushed the price up to 190p.’

Crooked writers are rare. Two other types of financial commentator can be dangerous to your financial health: the excessively vague and the excessively precise. How many times have you seen a share described in terms like these: ‘The shares stand on a PE ratio of 12, which is generous in today’s markets’. What does it mean? That the rating is generous to the investor (the shares are priced below their true worth and should be bought)? Or the rating flatters the company (the shares are over-rated and should be sold)? Take your pick.

Then the over-precise, which is most likely to crop up in the research circulars produced by Porsche-powered stockbrokers’ analysts but may well be repeated in the financial press: ‘The acquisition of Nuggins should contribute around £2.735m to the pre-tax profits of Bloggins Plc next year. Assuming internally generated sales growth in the range of 11.7 to 11.8 per cent and a 2.34 per cent improvement in the margins of the timber business, the shares at 393p are on a prospective PE ratio of 14.27 and are a medium to strong buy on a seven-month view’. Roughly translated, this might mean: ‘Your guess as to Bloggins’s profits is as good as mine. But our marketmaking arm has a whole load of Bloggins’s shares on its books and told me to help shift them. And it’s for writing this sort of junk that they pay me £80,000 a year.’

The big institutional investors know which stockbrokers’ analysts are worth reading. Most ‘research’ material goes straight in the bin, and one very large financial institution has a gigantic wheeled tub that goes round the investment department once a week to collect brokers’ circulars for the bonfire.

Much of what you read about the City falls into place if you bear in mind a few simple facts. Most financial people the private individual is likely to meet are salesmen of one kind or another. Like salesmen in other fields they’ll be tempted to sell you the product that pays them the highest commission or which they happen to have in stock. Like any salesmen, they are not always the best people to advise on the merits of the product.

They have a particular problem when markets are going down or likely to go down. ‘Put your money into Bloggins – you won’t lose more than half of it’ is not an appealing sales message. They have to convince themselves and their clients that markets are going up for ever. Or they devise strategies like ‘switching’ that generate commission income but fall short of a straight ‘buy’ recommendation. In either case the message is likely to be wrapped up in further layers of gobbledegook.

Hence: ‘Mike Puff, manager of the Duffer group of unit trusts expects to see the equity market rise by 20 to 25 per cent over the year after a weak start, given the relative strength of the UK corporate sector’. This might translate as: ‘Mike Puff has as little clue as the rest of us, but he’s in the game of flogging investments’.

Or the message from a broker to clients: ‘We therefore recommend a switch from Sainsbury to Tesco on income growth grounds. Our charts show that …’. The meaning here could be: ‘There’s damn all to choose between the two shares, but we rake in the commission each time you sell one and buy the other. We’ll recommend you switch back next year.’

Finally, no review of moneyspeak is complete without a glance at that bastion of City tradition: the daily stockmarket report. How often have you seen that shares ‘closed narrowly mixed in nervous trading’? The beauty of phrases of this kind is that the words can be used in almost any order with little if any change to the sense: ‘closed nervously in mixed narrow trading’, ‘traded nervously in a narrow mixed close’, and so on. Perhaps it means something to somebody. At least it fills column inches and helps to preserve the mystique of the financial markets.

Here’s a quick glossary of some common current terms and phrases you’ll meet, with possible meanings.

Overdue market correction A near meltdown of the financial system.

Free market A market in which share prices can be manipulated with relative freedom from official supervision.

Self-regulation Regulation of financial markets by the practitioners, for the benefit of the practitioners.

International (or global) market in securities A system for ensuring that a panic in New York or Tokyo spreads rapidly to London –or vice-versa.

Popular capitalism A device for selling shares in state monopolies to some of the people who already own them.

Insider dealer Investors who do not work in the City are ‘outsider dealers’.

The shares are acquiring strong institutional backing This is one the boys have decided to ramp up.

Our research report suggests … In a broker’s report on a new issue this may mean that what follows is a few unchecked facts gleaned from the company’s own prospectus.

Following the acquisition of Muggitt a phased programme of asset disposals was put in train We got control then asset-stripped it like crazy.

Acquisitive stockmarket-oriented financial conglomerate Paper-shuffling asset stripper.

Acquisitive Antipodean financial entrepreneur Aussie or Kiwi market raider.

Colourful usually linked with the word entrepreneur. It is not racist, neither does it usually imply blue blood. Colourful entrepreneurs are probably active stockmarket operators. While their tactics pay off they are in the pink. They attract acres of purple prose from the spivvier share tipsters and their competitors go green with envy or white with rage. All too often they overstretch themselves and end deep in the red.

Mr Rudyard Sharpe regards his 18 per cent holding in Nuggins as a long-term investment Ruddy Sharpe is bidding for Nuggins next week.

On a long-term view … Looking beyond the next five minutes.

We are responding vigorously to recent consumer complaint In a company report this may mean they are stepping up their public relations budget and running an image-building TV campaign – otherwise carrying on as before.

The accounts give a true and fair view … In the auditors’ report on a major bank this possibly means that the accounts give a true and fair view except that the £5 billion of loans to Latin America are worthless but can’t be written off because the bank hasn’t the resources.

… has been freed from day-to-day responsibility so that he can concentrate on long-term development of the company Has been fired. Employees are sacked; directors leave in a company Mercedes and a flood of euphemisms. When a director resigns for reasons of health, it is not necessarily his current health that is at issue. It is what will happen to his health if he tries to stay.

* * *

‘How to read between the lines’ is reproduced by kind permission of The Independent, in which a version of this section first appeared.