Watercolor sketch for an unpublished Prince Valiant story, 1991.

My father’s drawing board, tilted to its customary steep diagonal, stands across the room from where I write. Above it hang some of his paintings, sketches, and comic strips, along with work by other cartoonists and illustrators who were among his friends. The surface of the drawing board is five feet long and four feet high, and a polished declivity on the cross brace marks where my father rested his right foot as he sat and drew. Every square inch of the oaken face is covered with flicks and curls of paint or ink, creating an inadvertent pattern as intricate as a Pollock. That surface was the accumulated product of almost sixty years, from the late 1940s until my father’s death, in 2004.

If you had a sort of cinematic omniscience, you could connect each daub of ink and stroke of color to a moment of life in another world. I grew up in an unusual environment—not only as the child of a cartoonist and illustrator, but connected to a network of families where everyone’s father was a cartoonist or illustrator. In time, some among the younger generation would be drawn into the business themselves, as I was, collaborating with my father on Prince Valiant for many years. The place was Fairfield County, Connecticut. In the high summer of the American Century, during the 1950s and ’60s, it was where a populous concentration of the country’s comic strip artists, gag cartoonists, and magazine illustrators chose to make their home. The group must have numbered a hundred or more, and it constituted a tightly knit subculture.1 Its members sometimes referred to themselves as the Connecticut School, with the good-natured self-mockery that betrays an element of seriousness. In the conventional telling, the milieu of Wilton and Westport, Greenwich and Darien, was the natural habitat of the suburban salarymen who made the trip every day to jobs on Wall Street or Madison Avenue. Westport was the setting of The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit. I was well aware of the men (and it was almost all men) lining the platform every morning at the century-old train station in my hometown of Cos Cob. But for me, those executives with their briefcases—a majority of the county’s white-collar workforce—seemed like outlandish outliers. They weren’t living the way normal people lived.

To my seven siblings and me, and others we knew, “normal” was something else entirely. Normal was coming home from school and finding a father who had done nothing but draw pictures all day while watching Million Dollar Movie on TV. He might not have changed his rumpled clothes since throwing something on after rolling out of bed—and, yes, that could be a piece of rope holding up his trousers. He may have played a round of golf or enjoyed a long lunch with some of his other artist friends, so when you visited his studio after school you would perhaps have to rouse him from a nap. Or, in the absence of children to do the job for him, he might be posing in front of the Polaroid, pneumatic plunger in hand, to snap a picture of himself from a distance.

Normal meant appreciating the difference between “plate” and “vellum” finishes on three-ply bristol board—the one smooth as glass, ideal for pen and ink; the other slightly textured, better suited for charcoal or crayon. Normal meant understanding that a Hunt No. 102 pen nib was good for ordinary lines but that a Gillott No. 170 was best for lettering. It meant thinking of “bigfoot” as primarily an aesthetic category—designating humorous cartoons rather than adventure strips—and not a biological one. It meant being familiar with the terminology invented by Mort Walker, creator of Beetle Bailey and Hi and Lois—knowing, for instance, that the cartoon starbursts that convey intoxication are called “squeans” and the wavy lines that convey aroma are called “wafterons.”

Normal was listening to conversations like this one at a local restaurant, between Curt Swan, who drew the Superman comic book, and Jerry Dumas, who with Mort Walker produced Sam’s Strip and Sam and Silo:

DUMAS: Why does Superman have a cape?

SWAN: I don’t know, Jerry.

DUMAS: Why does Superman’s cape swirl around him even when he’s standing in an office?

SWAN: I really don’t know, Jerry.

DUMAS: When Superman undresses in a phone booth, how does he know his clothes will still be there when he gets back?

SWAN: I haven’t the faintest idea, Jerry.

DUMAS: Can Superman fly when he’s wearing his business suit on the outside, with the costume underneath?

SWAN: Pauline! Could you put a little brandy in this coffee?

* * *

At some point in the mid-1970s, Mort Walker and Jerry Dumas drew an aerial map of Fairfield County and wrote in the names of some of the cartoonists who lived there, quickly running out of room. Westport had a large cluster: Bud Sagendorf (Popeye), Leonard Starr (On Stage and Little Orphan Annie), Dick Wingert (Hubert), Stan Drake (The Heart of Juliet Jones and Blondie), Jack Tippit (Amy), John Prentice (Rip Kirby), and Mel Casson (Mixed Singles and Boomer). The great illustrator Bernie Fuchs was in Westport, too; imagine, my father would say, if Degas had worked for McCann Erickson and Sports Illustrated. Fuchs’s career was all the more remarkable because an accident at an early age had cost him three fingers on his drawing hand. Dick Hodgins Jr. (Henry), Dik Browne (Hi and Lois and Hägar the Horrible), and Whitney Darrow Jr. (a New Yorker maintstay) lived in Wilton. Stamford was home to Ernie Bushmiller, the son of a vaudevillian, who drew Nancy, a strip so spare and elemental (“Dumb it down,” Bushmiller would advise) that academic theorists can’t let it alone. Online you can find a cache of correspondence between Bushmiller and Samuel Beckett—it’s a parody, but so true to life that it has entered reality through the back door.2 Noel Sickles (Scorchy Smith, but also drawings and paintings that seemed to turn up everywhere) lived in New Canaan. So did Chuck Saxon, the John Cheever of gag cartoonists. Over a lifetime, Saxon’s evocations of self-satisfied but oblivious suburban grandees yielded 92 covers and 725 cartoons for The New Yorker. Up in the Ridgefield area were the gag cartoonists Orlando Busino, Joe Farris, and Jerry Marcus. Frank Johnson (Boner’s Ark and Bringing Up Father) was in Fairfield. Jim Flora, another illustrator, lived in an enclave tethered to coastal Rowayton. His edgy, angular confections—think of the album covers for any jazz artist in the 1950s and early ’60s—epitomized the era’s graphic sensibility of high-end hip. Also in Rowayton was Crockett Johnson (the comic strip Barnaby and the classic children’s book Harold and the Purple Crayon). Greenwich was home to Mort Walker and Jerry Dumas, and also to Tony DiPreta (Joe Palooka), the political cartoonists Ranan Lurie and John Fischetti, and my father (Big Ben Bolt and Prince Valiant). An adjoining parcel of New York served as an exurban annex, with Johnny Hart (B.C.), Jack Davis (Mad magazine), Dave Breger (Mister Breger), Ted Shearer (Quincy), and Milton Caniff (Steve Canyon and Terry and the Pirates). This is just a sampling, and leaves out scores.

drew an aerial map of Fairfield County and wrote in the names

Pen-and-ink sketch by Mort Walker and Jerry Dumas, the team behind Sam and Silo. The eponymous characters float above a landscape of cartoonists.

The surge into Fairfield County was mainly a product of the postwar years, and it had been driven by the age-old forces of money and geography. First, the artists and cartoonists needed to be close to New York City. That’s where the magazines and book publishers and comic strip syndicates were mainly based, and in an age before scanners or fax machines, physical proximity was essential. The gag cartoonists had to make weekly rounds in midtown Manhattan, going door-to-door to sell their work—this at a time when dozens of national magazines still ran cartoons. As for the comic strip artists, they were always running behind and often needed to deliver finished work in person. A cartoonist boarding the train in Westport during the late-morning, off-peak lull, a thin rectangular parcel wrapped in brown paper under his arm, would not have been surprised to meet someone he knew carrying a similar parcel boarding the train a few stops later, in Riverside or Greenwich. To anyone watching, the encounter might have seemed like a scene from John le Carré.

There are many ways of being close to Manhattan. You can actually live there, as some cartoonists continued to do, or you can live in the suburbs of New York, New Jersey, or Connecticut. This is where money came into play. Alone among the three states, Connecticut at the time had no income tax. Get yourself east of the state line and you would enjoy a tax holiday, with New York City only forty-five minutes away. Greenwich was the closest town in Connecticut to Manhattan; then came Stamford, Darien, and New Canaan. All were in the rectangular panhandle that Connecticut had somehow managed to keep away from grasping New York during the ferocious colonial disputes of the late seventeenth century—to the ultimate advantage of cartoonists and illustrators.

There was a third factor: Even before World War II, a few pioneers had begun to form a nucleus. In the first decades of the twentieth century, as comic strips and magazine illustration became big business, artists began migrating out of Manhattan to the comparatively rustic precincts of Westchester County, just north of the city. Hard as it is to believe for anyone who has seen its struggling downtown today, in the 1920s and ’30s the town of New Rochelle was what Greenwich would become. The cartoonist Fontaine Fox, who drew Toonerville Trolley, lived in New Rochelle, as did Frederick Burr Opper, who drew Happy Hooligan, and Paul Terry, who established his Terrytoons animation studio there. Also living in New Rochelle were J. C. Leyendecker, best known for the painterly Arrow Collar Man, and Norman Rockwell, a household name even then. My father had the luck to grow up two doors down from Rockwell, model for him as a boy, and train with him as a journeyman illustrator. I have a pencil drawing that Rockwell once made to suggest the composition for a painting my father had in mind. When Leyendecker died, his longtime romantic partner, Charles Beach, and his sister, Mary Augusta, auctioned off the contents of his studio from the front lawn of the Leyendecker home. For a few dollars apiece my father picked up sheaves of oil sketches—small oddments of canvas on which Leyendecker had experimented with color and form before making a finished painting. A few pink noses and ears. A muddy work boot. A shirt cuff. A choirboy. A propaganda poster. Disembodied hands making stylized gestures—devoid of context, but so expressive in themselves that they seemed to say “Shall we dance?” or “After you!”

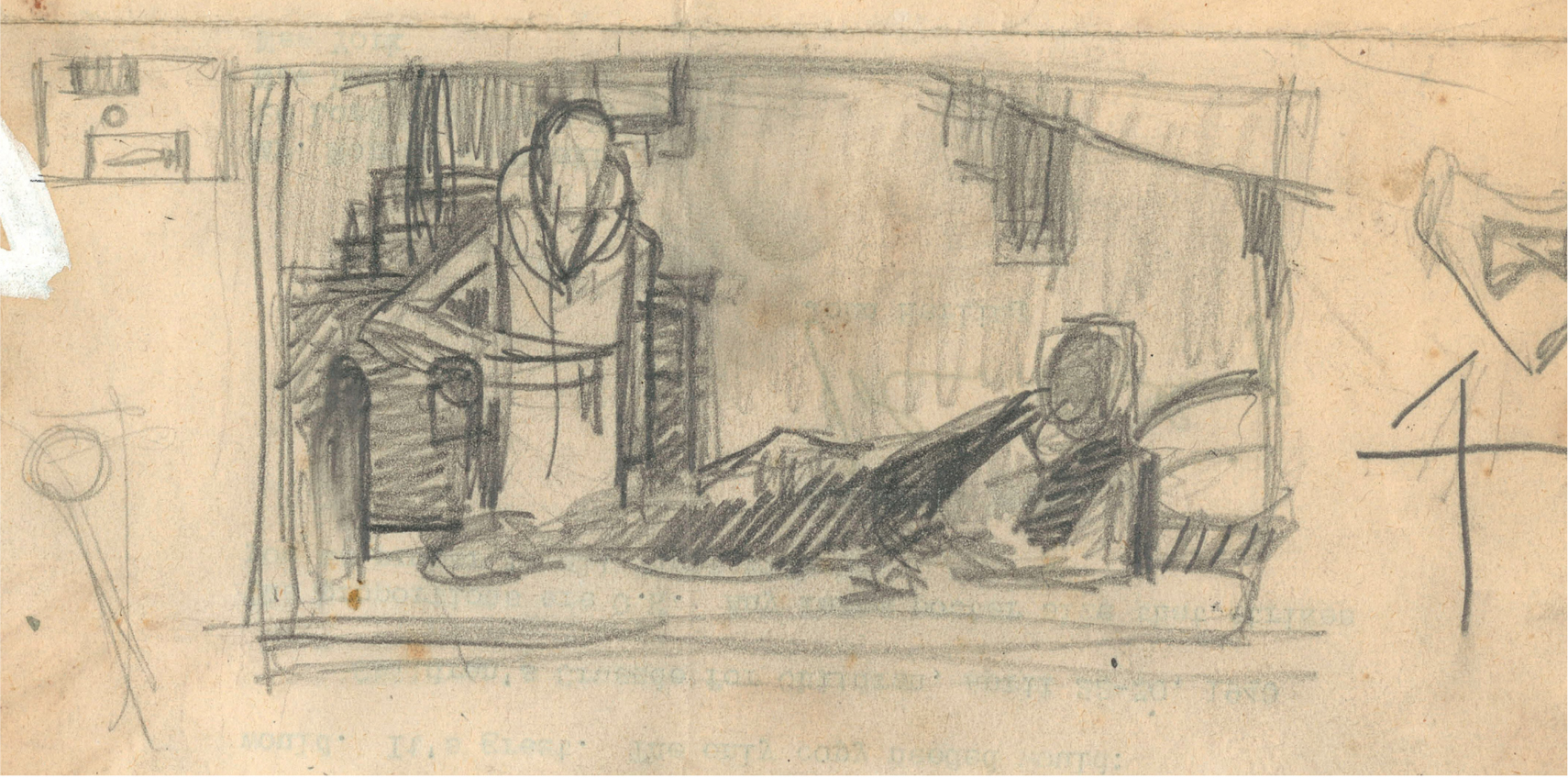

a pencil drawing that Rockwell once made

Outline by Norman Rockwell to suggest an arrangement of figures, 1937.

The painting by my father that followed, inspired by Ernest Hemingway’s short story “The Killers.”

That was in 1951, and the drift of illustrators and cartoonists away from Manhattan and Westchester toward the promised land of Connecticut was already under way. The Famous Artists School, which offered correspondence courses for aspiring illustrators and cartoonists, had been spun off from the Society of Illustrators and had established itself in Westport, under Albert Dorne. A dozen well-known commercial artists were on its faculty. Families were growing, and property in Connecticut was cheap. The contemporary image of Fairfield County and nearby areas is hard to escape, but the region was a very different place before the era of arbitrage and hedge funds. To be sure, there were old estates along the waterfront and in the backcountry—onetime summer homes for wealthy New Yorkers—and artists and writers had been putting down roots in this hinterland for decades, drawn by the wooded hills and shaded dells that could make a nearby neighbor seem far away. In the late nineteenth century, impressionists like John Henry Twachtman and J. Alden Weir established what Childe Hassam called the Cos Cob School of painting. By the middle of the twentieth century, Arthur Miller was living in Roxbury. Shirley Jackson was in Westport, Maurice Sendak in Ridgefield, James Thurber in West Cornwall. But there were still working farms all over southwestern Connecticut, and towns like Greenwich and Stamford, Norwalk and Darien, had a big middle class of plumbers and teachers who could afford to buy houses near where they worked and had a firm hold on the levers of local power. Greenwich Avenue, now lined with Ralph Lauren and Gucci, back then more closely resembled a prosperous main street in Ohio or Michigan. Cartoonists and illustrators didn’t earn fortunes, and didn’t need to. For our Addams Family–style house in Cos Cob, purchased in 1953, my parents paid $22,500. It came with a cavernous barn that still smelled of horses. My father’s weekly checks from King Features Syndicate would be left on the dining room table for my mother to deposit, so I know that his comic strip income in 1960 was about $25,000. This was for the boxing strip Big Ben Bolt, which appeared in three hundred newspapers—about average at the time—and was written by Elliot Caplin (who also wrote The Heart of Juliet Jones), the brother of the irascible Al Capp (who wrote and drew Li’l Abner). Only a very few strips, such as Blondie, Beetle Bailey, and Peanuts, ever hit the thousand-newspaper mark.

auctioned off the contents of his studio

Color studies by J. C. Leyendecker, oil on canvas, from among the many bought by my father at the yard sale after the illustrator’s death.

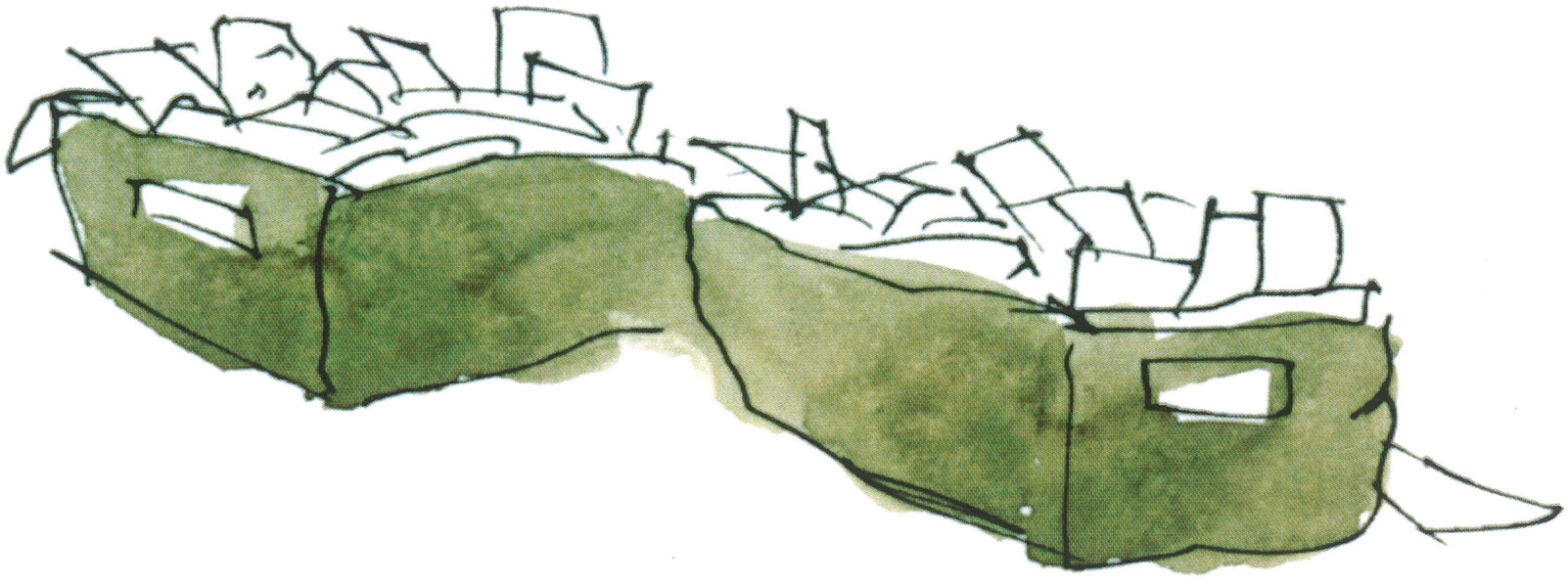

letters and drawings filled boxes that lined a hallway

A frieze of Beetle Bailey characters.

By the time I was old enough for childhood memories, Fairfield County was fully stocked with cartoonists and illustrators. What I know about the origins of the Connecticut School would come gradually in the form of backfill. Most of the cartoonists were military veterans, and many, like Dick Wingert, Bill Mauldin, Gill Fox, and Bil Keane, had worked during the war for the military newspapers Yank and The Stars and Stripes. Mort Walker had gone to college after World War II, then came east from Missouri and somehow landed a job at Dell as the editor of 1000 Jokes magazine, which paid the bills while he tried to sell gag cartoons to the weeklies and monthlies. His boss at Dell was Chuck Saxon, who was doing the exact same thing.3 Dik Browne, after a year studying art at Cooper Union, had gone to work for the New York Journal-American as a copyboy. He remembered walking into the newsroom for the first time, looking for a job. Bleary reporters pecked at ancient Underwoods. Editors hurled obscenities. Smoke rose in wafterons. The city editor took a cigar from his mouth and appraised the gawky kid in front of him. “What do you want?” he asked. Browne, taking in the surroundings, said, “I want it all.”4 When Browne’s talents as an artist became apparent, the Journal-American sent him to do courtroom sketches. He covered the Lucky Luciano trial, among others.5 After serving in the war as a cartoonist and mapmaker, Browne wound up at Johnstone and Cushing, an advertising agency that specialized in cartoon-style ad campaigns—the kind now enjoying a retro second life—and became a hothouse for aspiring gag and comic strip cartoonists. Milton Caniff worked there early in his career. So did Leonard Starr, Stan Drake, and the comic book master Neal Adams. Another type of hothouse was the production departments—the “bullpens”—at the big newspapers like the New York Journal-American and the Chicago Tribune, and at the newspaper syndicates, such as King Features and the Newspaper Enterprise Association.

James Stevenson’s rendering of unsolicited submissions to The New Yorker when he started there in the late 1940s.

Even after launching a strip, many cartoonists continued to write gags for magazines. For some, that was an entire career. In the middle of every week the gag cartoonists would take an early train into Manhattan for “look day”—Tuesday for a favored few at The New Yorker, which wanted a first lick of the cream (and which paid per square inch of published work), and Wednesday for everyone else. Wednesday was also look day at The Saturday Evening Post, Esquire, Sports Illustrated, Playboy, Argosy, Collier’s, True, and many other magazines, visited in descending order of largesse.6 Cartoon editors would flip through portfolios of penciled roughs, maybe selecting one or two to think about. The New Yorker’s James Stevenson remembered that, besides what the cartoonists brought in, some two thousand unsolicited ideas for cartoons would arrive every week at the magazine, “mostly from doctors and people in prison.”7 These letters and drawings filled boxes that lined a hallway. After their morning rounds, the cartoonists would meet for lunch at the Palm or the Blue Ribbon or the Pen & Pencil, continue their visitations in the afternoon, then meet for drinks at Costello’s on Third Avenue, the bar where Ernest Hemingway, in a display of manhood, once broke John O’Hara’s blackthorn stick over his own head.8

The editor Marione Nickles with cartoonists on “look day” at The Saturday Evening Post, mid-1950s.

Some events cast a long shadow. Though I was only four when it happened, the death of Alex Raymond in an automobile accident, in September 1956, would always loom as an epochal moment—for cartoonists, perhaps the equivalent of the Buddy Holly plane crash.9 Raymond was an acknowledged master—the artist behind Flash Gordon, Jungle Jim, Rip Kirby, and Secret Agent X-9, the last of these written for a time by Dashiell Hammett. Raymond’s younger brother, Jim, was a prominent figure in the business, too—he had taken over Blondie from Chic Young. With his thin mustache and brushed-back hair, Raymond had the dashing appearance of a 1930s aviator—a young Howard Hughes. (The actor Matt Dillon comes from the same family; Alex was his great-uncle.) Raymond’s work for Flash Gordon in particular was kinetic and rich, and matched by fast-moving plots in which Flash and his friends Dale Arden and Dr. Zarkov battle Ming the Merciless on the planet Mongo.

had the dashing appearance of a 1930s aviator

Alex Raymond at the drawing board in his Stamford studio, 1946.

Stan Drake, who was with Raymond in the car, would sometimes talk about the accident, and I heard his account myself on one occasion. It has also been written about. Raymond and Drake hadn’t known each other well, but Raymond had taken to stopping by Drake’s Westport studio, in part to see how Drake was using Polaroids to help create realistic poses and nuanced expressions. The technique was new to Raymond. Like Milton Caniff and others, he had sometimes hired live models, but usually relied on a blend of art school training and pure instinct born of long experience—he had probably drawn a human figure in published comic strips seventy-five thousand times by then. Drake had just bought a white Corvette convertible, and Raymond, who owned a Bandini and a gullwing Mercedes, and raced cars for a hobby, one day asked if he could take the Corvette for a drive. He was at the wheel on a narrow road in Westport, top down, driving about twice the speed limit, but still going only about forty. Drake was in the passenger seat. A light, misting rain had begun to fall, but Raymond didn’t want to put up the top. They came to a stop sign at the crest of a hill. As Drake would recount the story, Raymond suddenly said, “Oh!”—that was all—and the car shot forward and hung for a moment in the air. Drake remembered a pencil that had been on the dashboard seeming to float before his eyes. The car went off the road and smashed into a tree, killing Raymond instantly. No one knows exactly what caused the accident. Raymond was known to be reckless. Most likely his foot just slipped on a wet pedal and he hit the accelerator instead of the brake.

Milton Caniff working with models in the 1940s. The Dragon Lady (bottom) was a central character in Terry and the Pirates.

Jerry Dumas remembered Drake at a meeting of the National Cartoonists Society, weeks after the accident occurred, describing the terrible events moment by moment. The meeting was held at the Society of Illustrators, on East Sixty-third Street, and the upstairs room was packed. Chiseled portraits by Dean Cornwell and James Montgomery Flagg stared down from the walls. Drake had been thrown thirty-five feet from the car. His shoulder was broken. Portions of his ears had been torn and mended. When he spoke to his fellow cartoonists, he was still in bandages and wearing a sling. The accident replayed in Drake’s head throughout his life. Five years afterward, he went back to the scene. Bits of metal and plastic were still embedded in the tree.

* * *

Children arrive in a world already made. Their slates are blank, but all the slates around have long been written on. It was simply a given that both of my parents were selfless and energetic. That they could laugh at themselves and crack a joke. That they were politically conservative and believed in God. That my mother was outgoing, disciplined, and persuasive. That my father was a soft touch, and patient beyond reason. That his mind was an overstuffed attic whose door was ajar. That he could draw and paint. That even simple directions on a scrap of paper would be embellished with drawings of houses and trees, cars and cows.

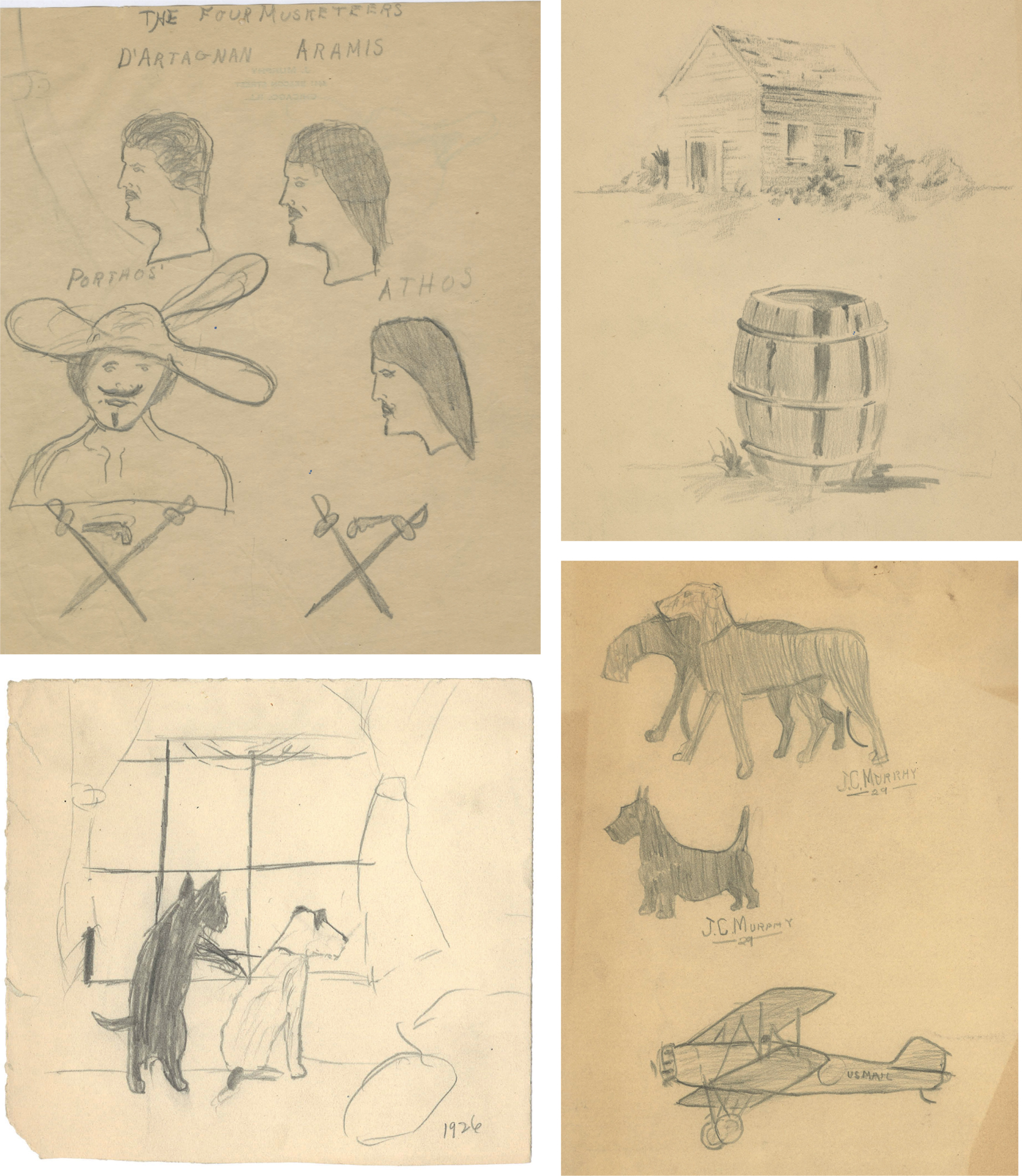

My father grew up in Chicago but was born in New York City. As if called by instinct to some distant spawning ground, his mother insisted on boarding the 20th Century Limited and returning to her native Manhattan whenever the time drew near for the birth of a child. He began drawing at a very early age—and also began carefully saving his work, as if for posterity, starting when he was about five. Given posterity’s likely interest, he also began saving his tests and papers from school. My father signed his work carefully, first as “Jack,” the name he was always known by, and sometimes as “J. C.,” and only much later with the full “John Cullen Murphy.” An artist of some kind is all he ever wanted to be if he couldn’t be a baseball player, which he accepted early on he could never become. Once, late in his life, when asked by a fan to answer twenty questions about himself, he filled in the blank after a question about what had inspired him to do what he did with the simple response “Liking it.” His family had an independent streak and a taste for the mildly unconventional, and encouraged him in his ambitions. His own father had been by turns a book publisher, a book salesman, and a literary agent whose most prominent client was the novelist and poet Christopher Morley. His mother’s family included artisans and craftsmen of various kinds. One of them was a coppersmith who produced elegant housewares and small sculptures in the mission style. My father enrolled in drawing classes at the Art Institute of Chicago when he was seven. A few years later, after the family moved back east, he attended the Phoenix Art Institute and the Art Students League, in New York.

carefully saving his work, as if for posterity

Counterclockwise from top left: “The Four Musketeers,” by a six-year-old John Cullen Murphy, and a selection of other childhood preoccupations, rendered at ages six, seven, and ten.

all he ever wanted to be

By age eighteen, caricatures and pencil portraits had become a staple. My father’s sketch of his older brother, Bob.

One unexpected stroke of luck was that his neighbor in New Rochelle was Norman Rockwell, whose studio on Lord Kitchener Road was about a hundred feet from my father’s back door. Rockwell had seen my father, then fourteen, with his unruly and very red hair, playing baseball at a field nearby—he looked like what we have come to think of as a Norman Rockwell character. Rockwell stopped by my father’s house one afternoon to ask his mother if young Jack could pose for some illustrations. In the ensuing years my father found himself appearing in Rockwell paintings. At age fifteen he posed as David Copperfield for Rockwell’s mural The Land of Enchantment, which is in the New Rochelle Public Library. As a cross-legged teenager he was on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post in September 1934, gazing at photographs of glamorous female movie stars. Starstruck is the title of the painting. A baseball glove sits by my father’s side, and a dog nuzzles at his knee. Rockwell once explained that, to make a posing dog or cat behave, you need only “apply a slight degree of pressure to the base of the cranium where it joins the spine.”10 In this instance, my father remembered, Rockwell also needed to add a sedative to the dog’s water.

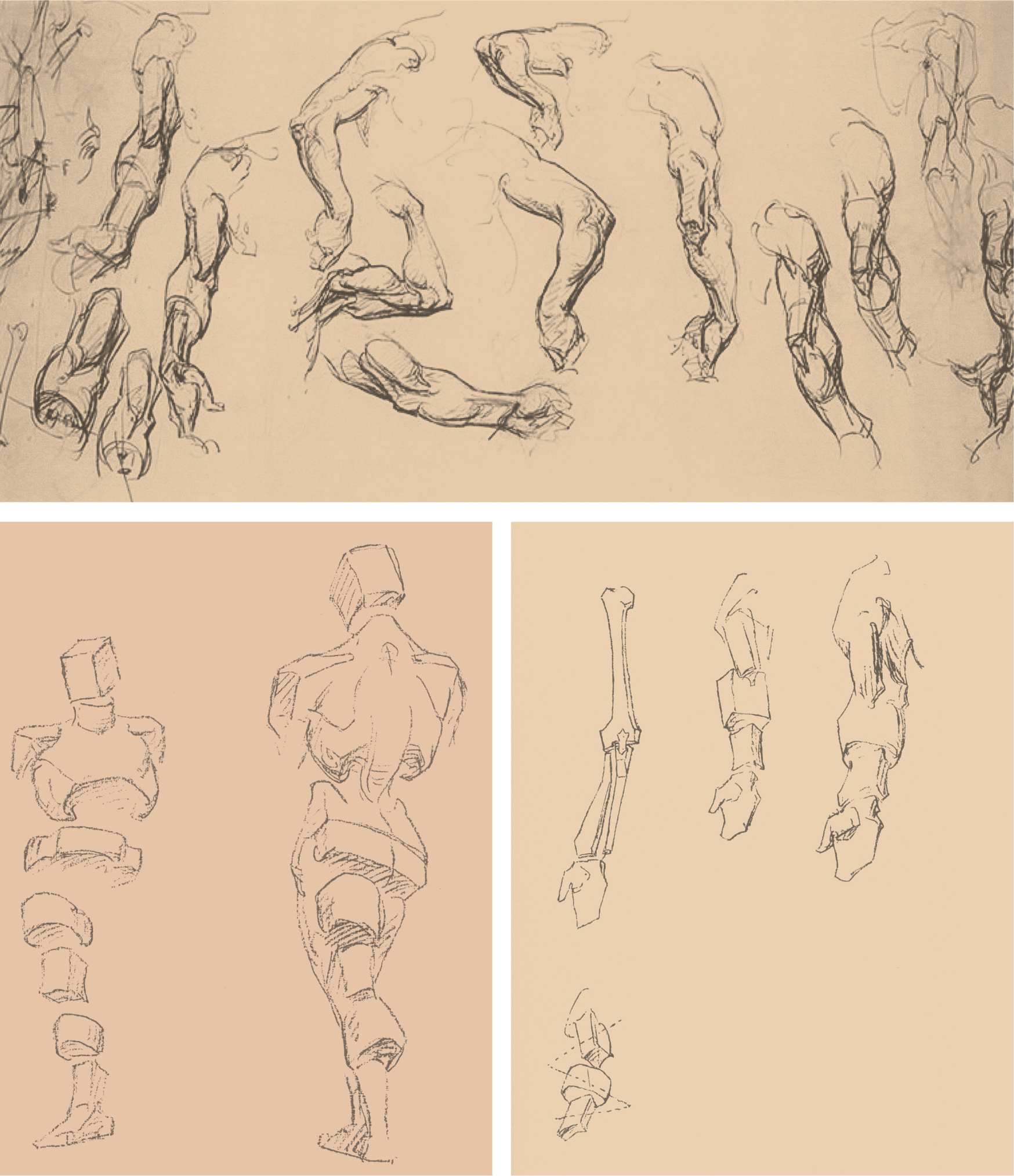

Rockwell was an important figure in my father’s life. He would assign my father short stories to illustrate, then critique the work and send him back to try again. He also taught him how to paint in oils. The sketch of Rockwell’s that I have was for an oil painting by my father of Hemingway’s story “The Killers.” Eventually Rockwell arranged a scholarship for my father at the Art Students League, where one of his teachers was Franklin Booth, whose meticulous pen-and-ink magazine drawings were a mainstay of Harper’s and Scribner’s. Another teacher, even more influential, was George Bridgman, who had been Rockwell’s anatomy instructor and ran a life-drawing class that Rockwell insisted my father attend. Bridgman had studied with Jean-Léon Gérôme in Paris in the 1880s. Gérôme had been trained by Paul Delaroche, who had been trained by Antoine-Jean Baron Gros, who had been trained by Jacques-Louis David, who had been trained by François Boucher, who had been trained by François Le Moyne—if you had time, my father could likely have pushed the laying on of hands back even further, through Raphael and Fra Angelico to some muralist at Pompeii. This sort of classical training was standard at the time—the cartoonist Chon Day had studied with Bridgman, as had Stan Drake, Bob Lubbers, Will Eisner, and a host of other cartoonists. So had Mark Rothko. The anatomical studies that resulted, done in chalk or charcoal, resembled exercises that might as easily have been done in 1550 or 1870 as in 1936. Bridgman entered the class promptly with an aroma of cigars, alcohol, and authority. When one student, who later became the director of the Whitney, resisted Bridgman’s criticism of his work, saying, “I don’t see it that way,” Bridgman replied, “Consult an oculist.”11 I was always struck by how many cartoonists had built their careers on a traditional foundation, and how easily some of them could shift from comic mode to a quick pencil rendering of a nude or a tree that would have seemed at home in the Frick.

found himself appearing in Rockwell paintings

My father on a magazine cover at age fifteen. The title of the Rockwell illustration is Starstruck.

By the age of seventeen my father had sold his first painting—of a horse race—to the Manhattan restaurateur Toots Shor and was drawing program covers for sporting events at Madison Square Garden, mainly boxing matches. In high school, he also developed his talent as a caricaturist; historically, high school has been an environment where that skill is in high demand. Within a couple more years, right around the time a much older Hal Foster was giving up Tarzan and launching Prince Valiant, my father had developed the style that would lead to covers for Sport, Liberty, Collier’s, Holiday, and other magazines. Becoming a cartoonist was not my father’s original ambition—it was an opportunity that came his way by chance after the war. He was intent on a career as an illustrator of magazines and books. And he remained an illustrator all his life, both in the kind of comic strips he drew and in the vast number of sketches and paintings he produced privately. In this he was like many other cartoonists. Most of them cultivated some complementary side of themselves that was more than a hobby and had nothing to do with what they were primarily known for. Jerry Dumas was an essayist whose spare, elegant drawings appeared in The New Yorker. Dik Browne created pen-and-ink landscapes and fantastical scenes that might have been etchings made by an impish Rembrandt. Rube Goldberg was a sculptor. Noel Sickles moved on from Scorchy Smith to magazine illustration—his drawings accompanied the first publication of Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea. Fred Lasswell, who wrote and drew Barney Google and Snuffy Smith, was an inventor—he came up with a method of producing comic strips in Braille and held a patent on a citrus-fruit harvester. Mell Lazarus, the creator of Miss Peach and Momma, was a novelist. Bill Brown, who wrote the comic strip Boomer, which was drawn by Mel Casson, had a sideline career on Broadway: he wrote The Wiz. Stan Drake, whose parents had been close to Art Carney, tried his hand at acting. Carney told him it was no kind of life, but the actor in Drake came out when he posed himself for pictures.12 Jerry Marcus, who drew gag cartoons for many magazines and also created the comic strip Trudy, dabbled as an actor in movies and commercials for most of his life. If you watch Exodus, you can see him for an instant in the role of a British soldier crossing a street in the far distance behind Eva Marie Saint. When Marcus ran into her years later, on the set of another movie where he had another bit part, he asked her if she remembered him. She said no. He said, “We were in Exodus together.”13

an aroma of cigars, alcohol, and authority

Studies by the life-drawing master George Bridgman. Classical training—and Bridgman himself—left a strong impression on generations of artists.

Pencil-on-newsprint life study by my father, done in Bridgman’s class, 1937.

cultivated some complementary side of themselves

A springtime comic strip landscape by Jerry Dumas, hand-tinted and used atop personal stationery.

A page by Dik Browne from Mort Walker’s 1973 book The Land of Lost Things.

the actor in Drake came out

A preliminary sketch by the cartoonist and illustrator Noel Sickles for The Old Man and the Sea, 1952.

My father’s fluidity with a pencil is one of my earliest memories of him, and a reliable and familiar constant ever after. There was a practiced thoughtlessness and an easy physicality to it that you also see in chefs and carpenters, barbers and tailors. He never sharpened a pencil mechanically. The tip was trimmed with a single-edged razor, the wood shaved off in thin wedges as the pencil turned in his fingers after each slice. When a half-inch shaft of graphite core had been exposed he then abraded the surface on a piece of fine sandpaper taped to the desk until the tip was properly sculpted. The effect he sought was not a symmetrically rounded cone, as a sharpener would produce, but something more like a scalpel, the graphite coming to a point, but with sides that were long and flattened. My brothers and sisters and I sharpen pencils like this even now.

Stan Drake, the cartoonist behind The Heart of Juliet Jones, experimenting with a range of attitudes for a promotional campaign in the mid-1950s.

As the pencil approached paper you could start to see his mind at work and the influence of Bridgman and his techniques, which were fundamentally architectural. He often began in an unexpected place—a nostril, a doorway—as if to put a stake in the ground. He then moved ahead lightly and loosely, the lines laid down in a way that at first seemed haphazard and chaotic until a sense of composition began to be discernible, like formless clouds gradually collecting into an image. He never used an eraser at this stage, but simply penciled over lighter lines with slightly darker ones as he grew more confident about what he wanted. His tendency was to move from the more general to the more particular, an approach that not only made sense when drawing but also reflected the conceptual hierarchy his mind applied to everything. He warned against getting too detailed too quickly—his favorite example was Michelangelo’s heartrending final Pietà, the one in Florence that the sculptor tried to destroy, with its polished arm and leg, expertly carved but hopelessly skewed in their overall proportions.14 The whole composition had been doomed from the start. “The masses of the head, chest, and pelvis are unchanging,” Bridgman had instructed. “Whatever their surface form or markings, they are as masses to be conceived as blocks.”15 Only when the basic structure was clear, and the blocks were in place, would my father move to the next level of concreteness, laying in the major shadows with the side of the pencil and then using the point to start the close work on prominent darker and sharper features—eyes, ears, hands, hooves, windows, branches. Time-lapse photography has captured the rapid, elegant arcs of a conductor’s baton; I wish my father’s graceful movements had been preserved the same way. His hand moved continually—settling in for a moment in one place, going back for a few strokes to another, coming again to where he’d just been—but there was nothing fussy or tentative about the motion. There was a sensation of inevitability: the picture starting to emerge had had no choice.

That was an illusion. For any cartoonist, the task of distilling some sort of invented reality into a series of blank spaces—one space for a single-panel cartoon, maybe three for a black-and-white daily strip, as many as nine for some of the color Sunday strips—took thought and preparation. For a humor strip or a gag cartoon, ideas were the engine, and the standard exchange rate was about one usable idea for every three or four you might come up with. Sometimes ideas struck suddenly—it often seemed that a cartoonist’s mind was trained to see all situations first as material and only second as lived experience. “I can use that!” is the phrase you’d hear. One day, Mort Walker was at the grocery store, lost track of his wife, saw a stock clerk shelving cans, and heard himself asking, “What aisle are wives in?”16 More often, ideas required “thinking,” which to an untrained eye could look like dozing in a rocking chair or hitting golf balls with a putter on the carpet.

until a sense of composition began to be discernible

Sketches done by my father on the fly in the late 1940s while he was in an antechamber in Rome among people awaiting an audience with the pope (top) and on the streets of Madrid (bottom).

Realistic story strips such as my father drew—or strips like Rip Kirby and Brenda Starr—needed something different. They started with scripts plotted out months in advance, and involved an ever-changing variety of new characters and new locales. Preparation meant research and the snapping of all those pictures. My father’s inventory of what he called “scrap” was organized alphabetically in a bank of filing cabinets. Once or twice a week he would sit with my mother in the evening, chatting amiably while riffling through a pile of newspapers and magazines, looking only at the photographs. When he came across an image that might someday be useful—a publicity still from Lawrence of Arabia, a family on muleback in the Grand Canyon, a fortification plan for the Tower of London, a prizefighter’s cauliflower ear, an adman mixing cocktails, a killer being led to the electric chair, a child weeping over a broken doll—he would tear it out with a sharp flexing of the wrist that was scissorlike in its accuracy. With a clean incision he moved vertically down the page to his target, then executed full removal with a series of swift right angles. He would file the pictures away according to a classification scheme that Linnaeus or Roget would never have proposed but could not have improved on. Ne’er-do-wells, General would be further broken down into subcategories like Swarthy, Femme Fatale, Irish, Armed, Seaborne, Cowardly. The category Combat was followed by thick folders labeled Swordplay, Arthurian, Jousts, Duels, WWII, Gladiators, Metaphorical. There was a vast section on crime, another on sports, yet another just on horses (Racing, Rearing, Grazing, Frightened, Furious). Romance was another big one: Young Love, Unrequited, Dancing, Spats, Matchmaking, Heartbreak. The fattest file of all was simply labeled Faces—a grab bag of people who might visually inspire a character: Auden, Arendt, Dirksen, Hepburn, Goldwater, Wharton, Acheson, Bacall, Keynes, Woolf. The scrap filled twenty-four file drawers.

This was the full extent of my father’s organizational prowess. Like most other cartoonists he was a virtuoso at the drawing board, but his powers diminished with the square of the distance from its surface. There were some notable exceptions, Mort Walker being one, but cartoonists by and large were not shrewd businessmen, and their managerial sensibilities were frozen in a premodern condition. Their reverence for masking tape, which they would have considered to be a sixth basic element had they been ancient Greeks, was symptomatic: it was the stopgap remedy of choice, suitable for all basic domestic repairs and most bodily injuries. That our own household functioned at all was due entirely to my mother, Joan. If my father was the Prince Consort, devoted to his curious projects, my mother was Queen, Prime Minister, Lord Chief Justice, and Chancellor of the Exchequer rolled into one. Both of them in their different ways were intensely involved in the raising of eight children, somehow making each one feel like the center of attention. In the early-morning hours of Christmas, presents would be shifted suddenly from one pile to another to correct a numerical or volumetric inequality. But it was mainly my mother who dealt with the child-rearing logistics. She kept our mansard-roofed Victorian from falling apart too quickly, controlled the checkbook, bought the cars, managed the calendar, and posed stylishly in front of the Polaroid whenever the casting call came from the studio. She also served as the back-office vizier when it came to renewing or renegotiating the contracts that governed my father’s work. When he returned from round one of any such meeting, there would be a quiet marital conference behind closed doors, punctuated by my mother’s audible sighs and the occasional “Oh, Jack.” Then she would devise a battle plan for round two.

whenever the casting call came from the studio

My mother, Joan, in the 1950s, performing for the Polaroid in her various recurring comic strip roles.

That an American comic strip industry could exist at all was due to an unseen army of women who played the role of irrepressible Blondies coping with the mayhem caused by all those clueless Dagwoods and their bright ideas. My mother had come from a large family known for its stamina and strength of will. Her own mother was decisive and imperious; she needed canes because of crippling arthritis, and leveraged them to effect when it came to parking spaces, tables at restaurants, and special favors from total strangers. She once was waved through to the gangplank at the Cunard pier in Manhattan by thrusting a metal forearm crutch through the car window and saying, “Officer, I have canes.” At home she used a crystal bell to summon help. It became a tradition to give her bells as gifts, making the wider family unwittingly complicit in its own servitude. My mother’s father, the son of an Irish maid in New York, had lost both of his parents by the time he emerged from his teens. Tutoring himself in trigonometry and other skills—I have copies of his meticulous notebooks—he became an aviator with the army during the Pancho Villa campaign, in 1916, then built a global career in maritime insurance. In a basement workshop his tools hung obediently inside crime scene outlines of each shape that he had drawn on the wall. Nails and screws were carefully organized, the twenty or so jars neatly labeled and lined up in a row. This was the stock my mother came from. Her organizational capacities were prodigious, sometimes outstripping what lesser figures might regard as prudence.

Having to send all those children off to school with homemade lunches was the kind of challenge my mother was born to solve. One September morning, before the start of the school year, a Bendix freezer the size of a sarcophagus was delivered to our home and installed in the basement. Later that day, my mother returned from the supermarket with a hundred or so loaves of Wonder Bread; large plastic pails filled with peanut butter, jelly, and mayonnaise; a hamper of egg salad; a butt of tuna fish; a hod of American cheese; and several yard-long tubes of sliced bologna. The age of artisanal sandwich-making was over. The era of efficient mass production had arrived. The family spent the day making the sandwiches we would consume for the entire year. As the hours went by, quality began to suffer. Episodes of industrial sabotage—peanut butter with bologna, tuna fish with jelly—afforded moments of amusement in the kitchen that would yield to horror in the classroom at a later date. The sandwiches were hauled down in bulk to the freezer, to be withdrawn as needed on school-day mornings. The Peasants’ Revolt came around February, when freezer burn set in.17

* * *

For cartoonists in America, the 1950s were the Cretaceous revolution. Conditions on planet Earth had never been so propitious. There were more newspapers than ever before—about three hundred that appeared in the morning, fifteen hundred that appeared in the afternoon, and five hundred that appeared on Sunday.18 Readership was at its peak. Those Sunday newspapers, with their thick comics sections, had a combined circulation of fifty million, which meant that more copies were being sold than there were households in America at the time. Postwar families were adding children to the population at a rate of four million a year.19 A surge in affluence and advertising supported print publications of all kinds. The growing ease of global communications also meant that comic strips could migrate overseas, as a few had done in the 1930s and many more did now. Predators could be seen on the horizon but were not an immediate danger. Television, a natural threat, was in its infancy and was as yet only in black-and-white. Radio was big, but obviously not visual. Photography, another natural threat and already a mainstay of Life, National Geographic, and a number of other publications, would not fully push aside illustration and reshape the entire magazine industry until the 1960s. The Internet, a threat the size of an asteroid, had been envisioned by the physicist Vannevar Bush in a famous Atlantic Monthly article, “As We May Think,” in 1945, but it would not materialize for half a century.

To a child and to many adults, Hearst’s Sunday comics supplement—syndicated as Puck the Comic Weekly to big-city newspapers—had all the magnificence of the Book of Kells. It was printed in color on a full newspaper broadsheet, about a foot and a third wide and a little under two feet high, and often ran to sixteen pages, for a total of about thirty-five square feet of comic strips. The color treatment that some strips required was demanding, and the printing quality of Puck was high—not a Taschen art book by any means, but sophisticated for a product that went to millions of people once a week, only to be thrown away within hours. Editors understood what sold—the news sections of the Sunday newspapers generally came wrapped in the comics section, not the other way around. Headlines about the hydrogen bomb or Eisenhower’s heart attack were concealed by the colorful doings of a parallel world. The pages were so big that for anyone less than a full-size adult, the only proper way to read the comics was to open up the newspaper on the floor and get down on your hands and knees.

I have a copy of Puck the Comic Weekly from a Sunday in March 1962, when I was ten years old. It opens, as it always did, with Blondie (befuddled Dagwood versus headstrong Blondie) and Beetle Bailey (hot-tempered Sarge versus carefree Beetle). Blondie was drawn by Jim Raymond, and even a child could see that its introduction to the dynamics of marriage, though stuck in a time warp, was comprehensive and often canny. Beetle Bailey was a mandatory stop. Mort Walker’s family was closely tied to my own by bonds of godparenthood and friendship. An exhilarating sense of secret knowledge came from reading a Walker strip in the Sunday comics that you may actually have seen on the drawing board nine weeks earlier. Even better was to see a sketch and know it had no chance of being published: for himself and his friends, Walker roughed out a lot of ideas that he knew were born to blush unseen. (At a bar, Miss Buxley’s date leans close and says, “I’d like to go where no man has gone before.” She replies, “Too late.”)20 Collections of Walker’s private stock have been published as books in Sweden.

all the magnificence of the Book of Kells

Examples of the broadsheet-size Puck the Comic Weekly, 1962, distributed as a Sunday supplement to Hearst newspapers nationwide.

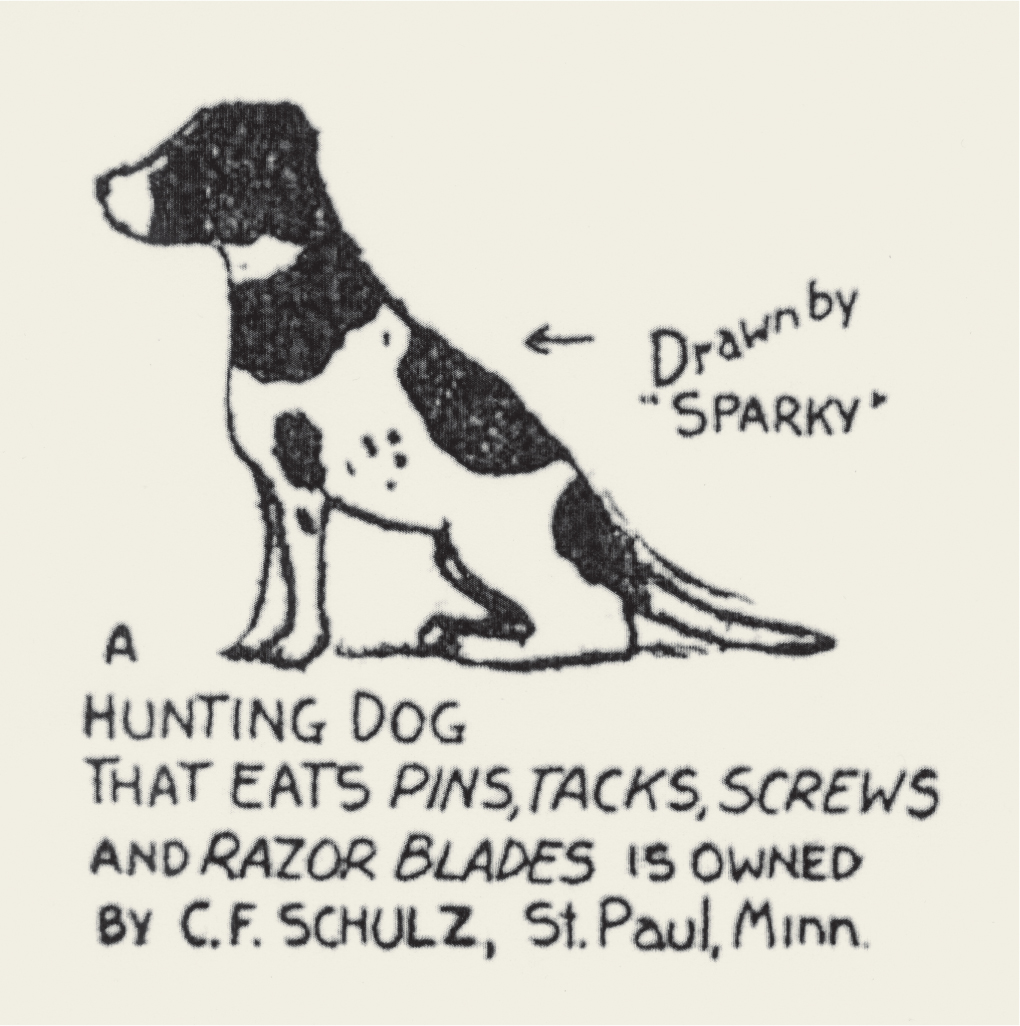

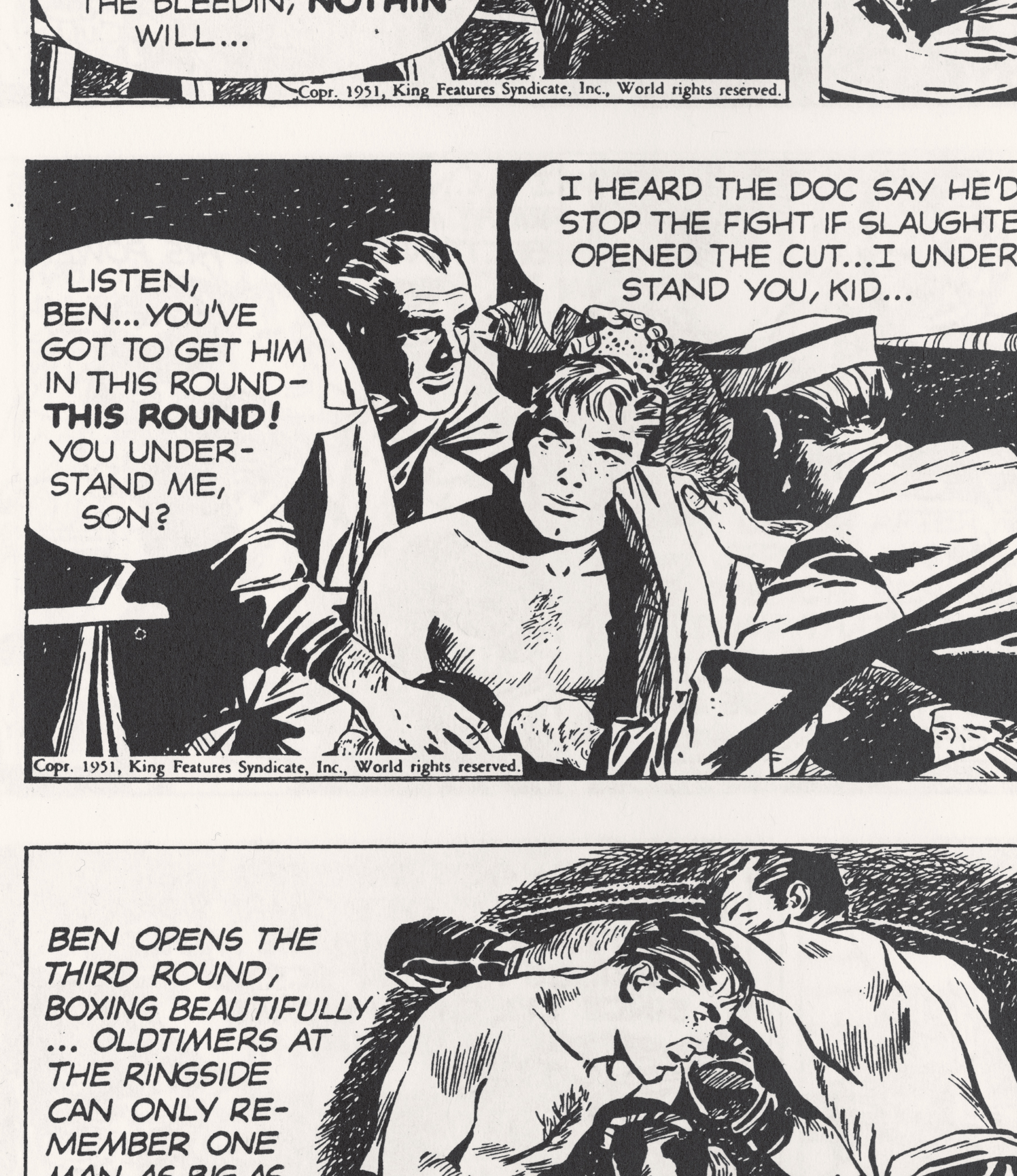

My father’s Big Ben Bolt was on page two, between The Phantom, with its atmosphere of mystery and menace, and Rip-ley’s Believe It or Not!, to which we accorded a presumption of inerrancy. Believe It or Not! was where Charles Schulz’s first published work appeared—in 1937, at age fourteen, he sent in a drawing of his omniverous hunting dog, and it was reproduced on the comics page.21 Ben Bolt was a prizefighter, though an unusual one—he had been born in Europe to American parents, came to the United States after the war, was accepted at Harvard, and lived on Beacon Hill with his closest relatives, a proper if threadbare and dotty Brahmin couple named Aunt Martha and Uncle Thaddeus. By the time I began reading Big Ben Bolt, its hero had pretty much given up the ring and was a journalist and detective, usually getting into hot water in the company of his rough-and-tumble trainer, Spider Haines, who was based on the fabled trainer and cutman Whitey Bimstein.22

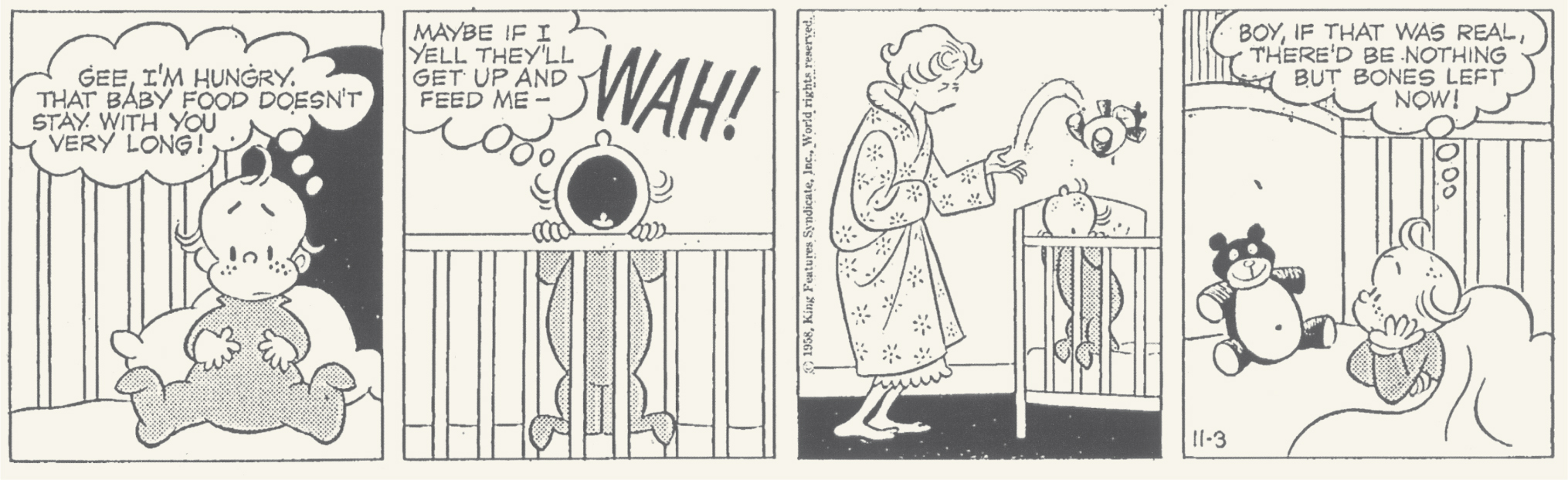

Then came Hi and Lois and Hubert. Hi and Lois could be read as the archetypal middle-American family strip, its gags derived from settings familiar to most people: school, kitchen, job, car. And it was a family strip in more ways than one: in the little-known backstory, Lois Flagston’s maiden name was Bailey—she was the sister of Beetle. But the strip had a subversive streak embodied in the character Trixie, the toddler who cannot talk but conveys knowing commentary and sometimes acid asides by way of thought balloons. Trixie was like Snoopy—the wise fool. In one of her earliest appearances she is tossed a stuffed animal by her mother every time she screams with hunger. In the last panel Trixie looks at the animal and thinks, “Boy, if that was real there’d be nothing but bones left now.” Dik Browne, who drew Hi and Lois, was a beloved figure, with that combination of ursine kindliness and ungainly affability that children find irresistible. He had a way of adding a quiet joke to everything he did. One afternoon he dashed off a sketch of my sister Cait, and before giving it to her, labeled it with a flourish, “Cait the Grait.” Browne also presented an alternative role model in terms of deportment. It used to be said of the sportswriter and columnist Heywood Broun that he looked like an unmade bed. Jerry Dumas considered Browne an unmade Heywood Broun. Mort Walker once described him as someone who appeared to be melting.23 To a youngster curious about the scope of possibility that adulthood might tolerate, Browne offered vast panoramas.

no chance of being published

A young Charles Schulz makes his debut in Ripley’s Believe It or Not!, 1937.

Pencil roughs by Mort Walker for Beetle Bailey strips that went no further.

Ben Bolt was a prizefighter, though an unusual one

The eponymous protagonist of Big Ben Bolt with Aunt Martha and Spider Haines on Beacon Hill, 1951.

The champ takes on the formidable Johnny Slaughter.

knowing commentary and sometimes acid asides

The silent but ever-thoughtful Trixie, Hi and Lois, 1958.

Dik Browne, who drew the strip, and his wife, Joan, mid-1970s.

The next spread was all Disney comics: Donald Duck, Uncle Remus, Mickey Mouse, and the rest—never my favorites. Most of them seemed a cut below the other offerings, and on top of that my father had once heard from an army pal that Disney’s behavior—he didn’t elaborate—could leave something to be desired. This assessment cast a pall on our enthusiasm. The paternal verdict on famous figures—Generalissimo Franco, Nancy Mitford, Ty Cobb, Norman Mailer, Queen Marie of Romania, Orson Welles—amounted to an indispensable moral tip sheet, and weighed heavily.

But the Disney pages were followed by They’ll Do It Every Time, Flash Gordon, Mr. Abernathy, and The Heart of Juliet Jones. The first of these, which captured moments of maddening behavior and familiar hypocrisy—the teenager who is Mr. How Can I Help? at school but avoids the household chores; the man who is ordered to the hospital for some rest, where interruptions make rest impossible—offered an introductory course in good-natured cynicism. It was drawn by an older man named Bob Dunn, who did magic tricks whenever children were around. Juliet Jones was not really a strip for a ten-year-old—it possessed a Mad Men–type sophistication, but possessed it in the actual moment, fifty years ago. Stan Drake’s drawing was expert and stylish, and the plots ran heavily in the direction of romance and melodrama. It was essentially a soap opera. But Juliet Jones had earned a lot of loyalty in our family. When my father came down with pneumonia, in 1960, Drake stepped in and drew Big Ben Bolt for three weeks. I remember him coming to the hospital to deliver finished pages and pick up new scripts, and my father commenting through the oxygen tent on how beautiful the women in the strip were becoming.

Turn the page and there was The Katzenjammer Kids—a strip that dated back to 1897—and The Little King. The latter was virtually a pantomime, drawn in minimalist style by another childhood favorite, Otto Soglow. Soglow was unusually short, making his ordinary-size head seem unusually large. He knew he was odd-looking—Sarge’s bulldog, Otto, in Beetle Bailey, was named for him—and leveraged this to comic advantage by adopting a stance toward the world of unflappable dignity. In this he was not unlike the Little King himself. Soglow had trained initially with Robert Henri and John Sloan, and his early work has all the Ashcan grittiness you’d expect. But then he went off in another direction. A pantomime strip is an exercise in stagecraft, sometimes surreal, and at heart Soglow was an actor who understood precisely the effect that his own controlled manner could have on other people. He worked for a time in a studio in New York that he shared with many others, and one afternoon some of Soglow’s colleagues decided to poke fun at his size by removing his full-size drawing table when he was out for lunch and replacing it with a tiny rolltop desk meant for a child. When Soglow returned, he made no comment, but simply sat down at the desk and went back to work.24

ran heavily in the direction of romance and melodrama

Panels from Stan Drake’s stylish The Heart of Juliet Jones, 1953.

a stance toward the world of unflappable dignity

The cartoon character the Little King, from the strip of the same name.

Its diminutive creator, Otto Soglow, comes face-to-face with an embodiment of the monarch at a cartoonist event, in the 1930s.

On the next spread: Popeye, Snuffy Smith, and Buz Sawyer. Bud Sagendorf, who wrote and drew Popeye, was famous in our household because he worked only at night and slept till noon, which endowed this otherwise ordinary fellow with a patina of exoticism. Roy Crane, the man behind Buz Sawyer, had been something of a drifter who took art lessons by way of correspondence school and started out penciling roughs for H. T. Webster, the creator of the enduring character Caspar Milquetoast. But Crane’s tastes ran to adventure—embodied first in Captain Easy, about a swashbuckling soldier of fortune, and then in Buz Sawyer, about a globe-trotting oilman and troubleshooter. Buz had tantalizing connections with the Pentagon and the CIA, and it was obvious even to a youngster that his pugnaciously anti-communist outlook was completely in synch with America’s Cold War foreign policy. One episode in the 1960s even made reference, without demur, to the dropping of napalm in Vietnam. No one suspected that the State Department was sending Crane memos with detailed story ideas, which he sometimes used, and urging him, for instance, to “stress importance of Private Enterprise.”25

Finally, at the end, on a full page, came Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant, a masterpiece of drama and draftsmanship. To encounter Prince Valiant after all that had preceded it was like turning a corner and stumbling on The Night Watch. Tall, trim, and confident, Foster cut a distinguished figure, the effect enhanced by a natural reserve. As with many laconic people, a sense of humor was revealed in his work rather than in his life. An undertone of lofty comedy ran through the tumultuous adventures of Prince Valiant, comedy of the bluff or coquettish kind that you’d find in Sir Walter Scott—the swaggering braggart getting his comeuppance, the lowly wench cleverly turning the tables, the besotted youth dithering in helplessness before his beloved’s wiles. But you almost didn’t need to read the strip to enjoy it. The pictures, in a style that had emerged from that great age of book illustration a hundred years ago, were richly detailed and dynamically composed. Every few months Foster would take two-thirds of a page and create a single glorious panel, about two feet square, as if to demonstrate the heights he could have reached if they’d just given him the whole newspaper. His stated rationale for these panels was more prosaic: the metabolism of any adventure slows down from time to time, and those are good moments for spectacle. As he once put it, “Every so often you have to bring on the elephants.”

The strips in Puck were all from a single syndicate, King Features. Pick up a different newspaper with a different syndicate and you’d have a different lineup—Peanuts and Ferd’nand and Tarzan, say, or Dick Tracy and Dondi and Moon Mullins. In the early 1960s, newspapers had about a hundred and fifty comic strips or panel cartoons to pick from. This riot of enterprise was generally produced in a state of calm, by people laboring more or less alone. The particulars varied from place to place, but the story always began with a man sitting by himself at a drawing board for long stretches at a time. At our Cos Cob home, the studio stood at the back of the property, next to the barn. It was shielded from the house by a large apple tree. My father would leave the kitchen as his children were having breakfast. In one hand he carried any mail that had arrived the previous day, along with any scrap torn the night before from newspapers and magazines. In his other hand he carried a cup of milk to add to the tea or coffee he would make throughout the day.

as if to demonstrate the heights he could have reached

On the bridge over Dundorn Glen, Prince Valiant and the Singing Sword keep a Viking horde at bay, 1938. One of Hal Foster’s finest Prince Valiant panels.

If the house itself was loud and boisterous, the studio was a sanctuary. It was where many of the more serious family conversations took place—about squabbles, school, sickness, ambitions, love. When we were young, it was also the disciplinary destination of last resort. For most infractions, my mother served as police, forensic squad, prosecutor, defense attorney, and judge, and there was never any backlog in her court. The studio was reserved for capital crimes: “Go tell your father what you’ve done!” Never mind that, in reality, my father was the furthest thing from an Old Testament judge you could imagine; a look of disappointment was the mandatory maximum and was indeed punishment enough. But the command to go forth to the studio had an effect on those left behind. Tutored by movies, we expected to see the lights flicker in the Big House as Old Sparky did its job in the death chamber out back. The miscreant, meanwhile, would have plea-bargained the sentence down to a cup of hot chocolate.

A bank of musty filing cabinets took up one wall of the studio. The other walls were hung with original strips drawn by friends and with old photographs from the war or of family and friends and of people my father knew in professional sports. One nook functioned as a costume shed. It was partly concealed by a mission-style rocker and a pair of wooden easels holding private work in progress. A tall photography lamp stood wherever it had last been rolled.

It took seventy-five of my father’s steps, each lighter than the previous, to cover the distance from the kitchen door to the studio, and I remember noting, as I grew older, how the number of steps I needed—a hundred and fifty or so at the outset—gradually began to converge with the number that had come to symbolize maturity. Once inside he would flick on the light, file away the scrap, and sit down at the drawing board. Selecting a pencil, he freshened the point on sandpaper, and then started in.