The Artistry of Mary Whyte

On the stairway leading up to her Seabrook Island studio, Mary Whyte has inscribed the following words in a calligraphic script:

Coraggio

Ispirazione

Visione

Perseveranza

Forza

Fantasia

Fede

These words have served as the artist's guiding principles, and are encapsulated in her life and her art. She selected Italian as a reminder of the year she spent in Rome as an art student, and, perhaps, because that language is uplifting and inspirational. With their longstanding commitment to an artistic and operatic way of life, Italians are consummate models for a dedicated and ambitious painter who feels passionately about her art and her subjects.

Coraggio, or courage, describes the way Whyte chooses her subject matter and the conviction with which she practices her profession. Usually she is an outsider who makes tentative steps to get to know her sitters, whether they are members of a rural Amish community in Ohio or Gullah women in South Carolina who gather weekly to make quilts. She succeeded in earning the trust and the affection of the latter; Alfreda, the titular head of the group, even called Whyte “my vanilla sister.” Their mutual feelings of love and friendship radiate from such paintings as Red, where Alfreda is decked out in a brilliant Sunday hat. Courage was also called for when Whyte donned a cumbersome suit and mask so she could experience firsthand the responsibilities of beekeeping. Beekeeper's Daughter reflects her appreciation and understanding of how smoking the bees calms them down.

September, 2003

Watercolor on paper, 47 × 39 ½ inches

Collection of TD Bank

Red, 2009

Watercolor on paper, 18 ½ × 18 ½ inches

Private collection

Beekeeper's Daughter, 2008

Watercolor on paper, 28 ¾ × 21 ¾ inches

Private collection

It also took a good deal of nerve for Whyte to approach a rough and dirty threesome in a diner, but she was curious about their occupation, wondering if it would fit into her series featuring vanishing industries across the South. The three men agreed to let her sketch them, and the end result is the compelling Fifteen-Minute Break, one of the grittiest paintings Whyte has ever done.

Ispirazione, or inspiration, is what Whyte derives from the people she paints, the scenery she passes as she drives through the countryside, and the colors and textures she relishes painting.

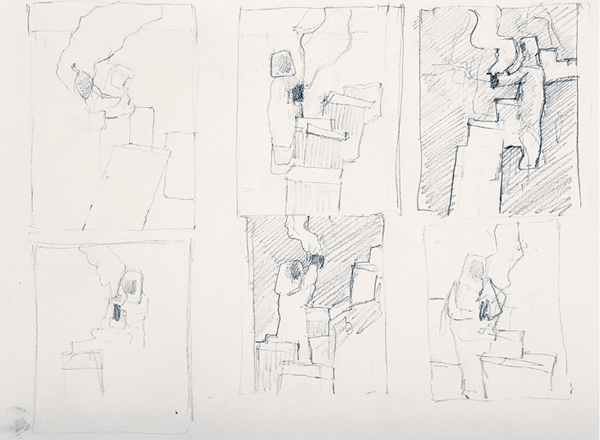

Thumbnail sketches for Beekeeper's Daughter, 2008

Graphite on paper, 12 × 8 ¼ inches

Collection of the artist

“Many of the ideas for my paintings start with a fleeting glimpse: a figure hanging laundry, a shadow of a tree, a snippet of a shrimp boat on the river in the distance. Seeing these unfinished stories is sometimes like hearing only the middle words of a conversation and having to imagine the beginning and the end. These tiny flashes of life are sometimes the catalyst for a major series of works. For me ideas are more plentiful than the hours to paint them, and I worry that I cannot get to all my thoughts before they are forgotten or are pushed aside by more pressing concerns.” She speaks of how she might see a camellia bush in bloom and wonders to herself what Tesha might look like if she stood before it. Tesha Marsland has been Whyte's model since the early 1990s, and she has posed with horses, in doorways, and in chicken coops. She has developed a very comfortable working relationship—and friendship—with the artist. The painting Waiting has special meaning for both of them: Tesha had just learned that she was pregnant, telling Whyte, who then conveyed both quiet joy and anxious weariness in the final composition. It remains Tesha's favorite painting.

Close-up of Fifteen-Minute Break

Fifteen-Minute Break, 2008

Watercolor on paper, 58 × 38 ¾ inches

Collection of the Greenville County Museum of Art

Summer Solstice, 2003

Watercolor on paper, 30 × 39 ¼ inches

Private collection

Explorer, 2008

Watercolor on paper, 27 × 20 inches

Private collection

End of High Tide, 2009

Watercolor on paper, 18 ¼ × 20 ¼ inches

Private collection

Music Men, 2007

Graphite on paper, 10 ½ × 7 ¾ inches

Private collection

Waiting, 2002

Watercolor on paper, 40 × 27 inches

Private collection

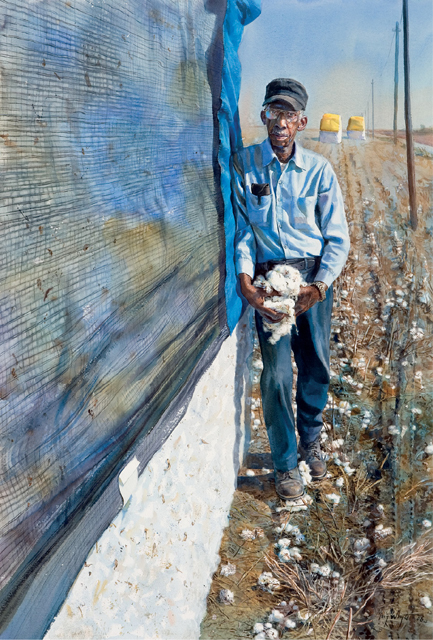

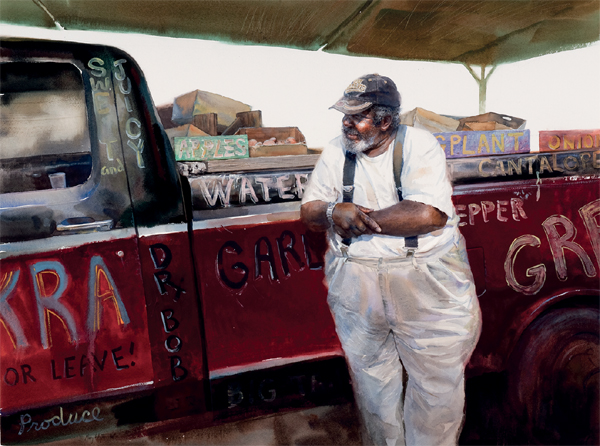

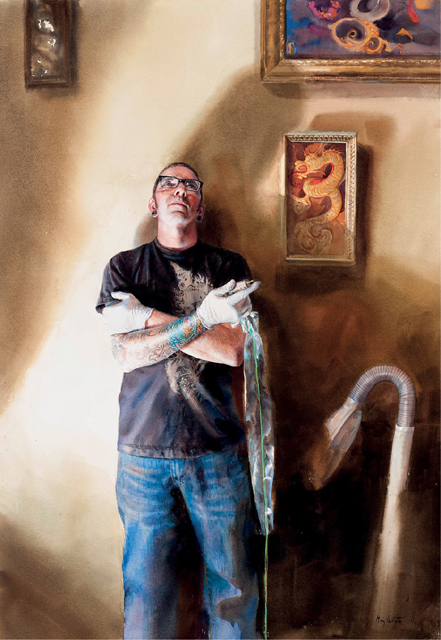

Visione, or vision, is represented by Whyte's ability to see beauty in ordinary things and people. “I'm a genre painter who depicts people under the radar,” she explained when describing herself and her sitters. Her vision impels her to take on new challenges and not become complacent. For the Working South project, she dedicated almost four years to the thirty watercolors that illustrated her theme and required her to travel far afield from Union City, Tennessee, to Miami, Florida, and lots of small towns in between.

Outbuilding with Chickens, 2011

Watercolor on paper, 11 × 9 inches

Private collection

Shoe Shine, 2008

Watercolor on paper, 25 ¼ × 23 inches

Private collection

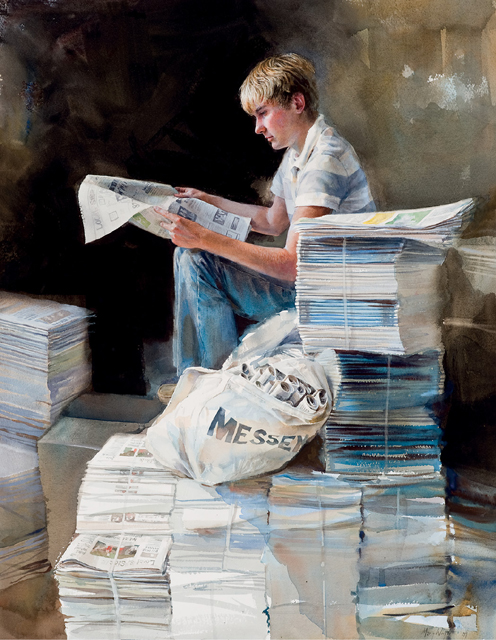

Whyte's perseveranza, or perseverance, and discipline have allowed her to juggle all that she does: painting meticulously rendered watercolors, teaching four to six workshops annually, and producing books and DVDs, all at an apparent leisurely pace. While Working South was on view at the Greenville County Museum of Art during 2011, she offered numerous lectures, gallery talks, and book signings, reaching an audience of more than eleven thousand. In the DVD Watercolor Portraits of the South with Mary Whyte, she demonstrates her working method—lots of quick sketches, finished studies, and photographs—and shows the demanding task of painting the details of Tesha's right eye, mouth, and hair. She patiently and deliberately applies each stroke while providing an articulate and insightful commentary.

One of the most engaging segments of the video is of a chicken in Coop; the hen comes alive as Whyte mixes her favorite colors, ultramarine blue and burnt sienna, to simulate its feathers. In Painting Portraits and Figures in Watercolor, she declared, “No accomplished artist was brilliant right out of the chute. Every one of them had to pay his or her dues with hundreds of drawings and paintings. The key is to learn from failed works and understand what went wrong.”

Furthermore her passion for watercolor compounds the challenges. “Watercolor, as any of the serious arts, takes considerable patience, fortitude, and practice. If mastering the medium were easy, everyone would be an adept watercolorist and the medium would lose its magical appeal. Becoming an accomplished artist requires years of earnest effort to master drawing, composition, color mixing, and technique.”

Forza in Italian literally denotes “force,” but it can also be translated as strength. Mental, emotional, and physical strength are necessary to Whyte's modus operandi. “Painting is largely a solitary endeavor that requires enormous concentration…. I need a quiet place where I know I can have several hours of uninterrupted time.” She sometimes goes off for a month at a time in a new location, just so that she can concentrate on her work.

Slicker, 2010

Watercolor on paper, 18 × 17 ½ inches

Private collection

Sketches for Slicker, 2010

Graphite and watercolor on paper, 12 × 8 ¼ inches

Collection of the artist

Coop, 2011

Watercolor on paper, 28 ¼ × 40 ¾ inches

Private collection

She often paints en plein air—a French term for painting out of doors—and in South Carolina that can mean painting in hot and humid conditions. To optimize the light Whyte starts early in the morning and usually limits her sessions to less than two hours. She wears a hat with a wide visor so the sun does not get in her eyes and either a black, white, or gray top so that its color is not reflected on her paper. For her everything is carefully planned and worked out in advance. Strength is also a quality she finds in many of her sitters, as exemplified by the man in Hull, his power echoed by the imposing timbers above him, or the spiritual force observed in Soul Rising.

Miss Lewis in Pearls, 2012

Graphite on paper, 15 × 11 inches

Private collection

Hull, 2008

Watercolor on paper, 37 × 29 inches

Private collection

Cemetery, New Orleans, 2004

Watercolor on paper, 10 ½ × 12 inches

Collection of the artist

Soul Rising, 2003

Watercolor on paper, 29 ¼ × 22 ¼ inches

Private collection

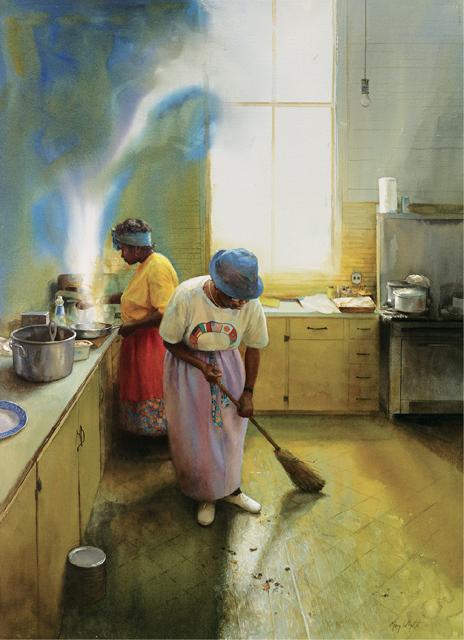

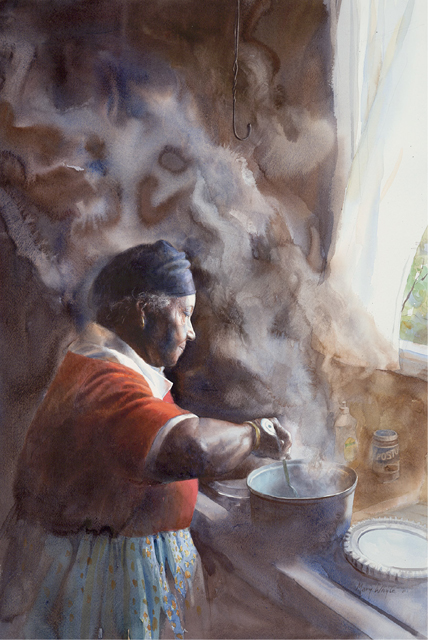

Fantasia, fantasy or imagination, is embodied in many, but not all, of Whyte's paintings. Something of a storyteller, Whyte frequently poses her figures in a state of reverie, allowing the viewer to fill in the accompanying narrative. In many of her compositions, individuals are active at some kind of task: sweeping the floor, ironing, or cooking.

Often a sense of nostalgia pervades the painting—wistfulness for a time when things were simpler, less hurried, less complicated. Enhancing this retrospective mood, Whyte often paints her subjects enveloped in smoke and steam vapors that literally blur harsh details. Her talents as an illustrator reveal a capacity to translate a fantasy into vivid imagery, as she did with the children's picture book Snow Riders.

Ironing, 2009

Watercolor on paper, 29 × 21 inches

Private collection

Snowball from Snow Riders, 1995

Watercolor on paper, 18 ½ × 27 ½ inches

Collection of the artist

Fede, or faith, is something Whyte has in abundance. Faith in herself, her art, her sitters, and her God. She believes it is through the grace of God that she has achieved a certain level of success and gathered thousands of admirers across the country. In Down Bohicket Road—a reprise and expansion of her earlier book Alfreda's World about residents of Johns Island—Whyte frequently portrays and quotes women praying and referencing God.

The artist is grateful for all that she has been given, reads the Bible daily, and regularly attends the Episcopal Church of Our Saviour on Johns Island. When the congregation was raising money for a new parish hall, Whyte and her husband, Smith Coleman, a master frame maker, decided to make a unique gift of their shared creativity: four large, gilded oil paintings representing angels playing musical instruments.

Using multiracial models from the church's vacation Bible school, Whyte painted them as the four seasons; verses from Isaiah, beginning with “Sing a New Song to the Lord,” are inscribed on the handcrafted frames. Gilding highlights instruments and other details in airy fanciful settings that combine fresh young faces with flora and, in one case, goldfish. Coleman described the project as a labor of love: “You don't think about the hours. You just think about the result. This doesn't seem like work.”

Missing from the steps leading to Mary Whyte's studio is any specific reference to process or technique. Yet even a quick look at one of her paintings tells the viewer that she is a facile technician. She is a dedicated draftsman who relies on quick sketches and preparatory drawings to work out the fundamentals of her compositions. For instance, the Cubist-looking “thumbnails” in her sketchbook for Beekeeper's Daughter (page 5) reveal her methodology and concern for both geometric shapes and positive and negative space. Although from time to time she paints with oils, her real forte is watercolor, which she believes is closely linked to her preferred subject, people. “Watercolor is the essence of the human spirit: it is lively, spontaneous, engaging, unpredictable, beguiling, and has a will of its own. It has so many of the characteristics we humans do, why shouldn't it lend itself to painting portraits? Watercolor's natural luminosity can easily duplicate the fresh translucent look of skin, as well as aptly render interesting textures of clothing, hair, backgrounds, and atmosphere.”

Devotional, 2000

Watercolor on paper, 21 × 27 inches

Private collection

Hidden, 2011

Watercolor on paper, 15 ½ × 15 ¼ inches

Private collection

Gilded Quartet: Spring, 1999

Oil and gold leaf, 52 × 40 inches

Collection of the Church of Our Saviour, Johns Island, S.C.

Gilded Quartet: Summer, 1999

Oil and gold leaf, 52 × 40 inches

Collection of the Church of Our Saviour, Johns Island, S.C.

Gilded Quartet: Fall, 1999

Oil and gold leaf, 52 × 40 inches

Collection of the Church of Our Saviour, Johns Island, S.C.

Gilded Quartet: Winter, 1999

Oil and gold leaf, 52 × 40 inches

Collection of the Church of Our Saviour, Johns Island, S.C.

Close-up of Gilded Quartet: Spring

Two paintings beautifully exemplify Whyte's ability to articulate flesh: Lovers, with its rendering of the wrinkled, vein-ridden, translucent skin of an older woman, and Spinner, where the soft face of the African American millworker is clearly moist with perspiration. Absolution and Firefly Girl showcase her talent for depicting hair and textures, and with its riot of foreground flowers and hazy horizon, Goin' Home demonstrates Whyte's gift for capturing a fresh and airy outdoor scene.

Lovers, 2008

Watercolor on paper, 26 ½ × 27 ⅛ inches

Private collection

Close-up of Lovers

Spinner, 2007

Watercolor on paper, 28 ½ × 36 ½ inches

Collection of the Greenville County Museum of Art

Absolution, 2010

Watercolor on paper, 22 ½ × 28 ½ inches

Private collection

Close-up of Absolution

Goin' Home, 1993

Watercolor on paper, 20 × 26 ½ inches

Private collection

Firefly Girl, 2006

Watercolor on paper, 20 × 28 ¼ inches

Private collection

Watercolor is known as a willful medium, and it must be carefully controlled by the artist at all times. In this respect Whyte is its master, capable of tight and precise details—the result often of a dry brush that has little water on it—and runny expanses that express wind blowing, smoke rising, and water moving.

Whyte maintains that watercolor technique can be taught, and she has spent countless hours doing just that in her workshops, books, and DVDs. For her, however, good art is more than just technique: “I believe having the creative ‘idea’ and passion to express it is the one component of art that can't be taught. It must be an intrinsic part of the student's personality.”

At heart Whyte is a storyteller, following a venerable American tradition, and it is appropriate that she uses watercolor, a quintessential American medium. For Whyte the stories often need time to take shape, and accordingly her medium is a good match. “Some works take time to evolve. Like small seeds the paintings might not come to fruition until several years later, after there has been ample time for germination. To my mind watercolor is the only medium that matches the speed and the nebulousness of these stories as they unfold. Washes can be done quickly and loosely, making the unseen come to life.”

Little Love, 2004

Watercolor on paper, 22 × 24 inches

Private collection

Rooster, 2010

Watercolor on paper, 20 ¾ × 20 ¾ inches

Private collection

Steam Iron, 2002

Watercolor on paper, 27 ¾ × 20 ¾ inches

Collection of the Greenville County Museum of Art

Persimmon, 2012

Watercolor on paper, 40 ¾ × 28 ¾ inches

Collection of the artist

Abyss, 2009

Watercolor on paper, 30 ¾ × 23 ¼ inches

Private collection

Ferry, 2008

Watercolor, 8 ¾ × 10 inches

Private collection

A Lady Bug's View of the World, 1970

Oil on canvas, 17 × 23 ¾ inches

Private collection

Mary Whyte grew up in rural Bainbridge, Ohio, about twenty-five miles east of Cleveland, her actual birthplace in 1953. The family home was a rambling house on twelve acres with woods, two streams, an apple orchard, and a setup for trap shooting. The address was Chagrin Road, which led to the nearby town of Chagrin Falls, where the young artist often biked to use the library.

From an early age Whyte aspired to be an artist. In the second grade, when she wanted pictures for her room, her mother, Betty, encouraged her by saying, “if you want art in your room, draw it yourself.” One of her first artworks was a copy of a Winnie the Pooh illustration. Her first studio was her bedroom, where the windowsill or her bed served as her easel. Her father, Donald, supported her youthful ambitions and gave her a set of oil paints; her first oil painting was a fanciful reverie of a boy on a log playing with his sailboat.

A Boy and His Dog, 1965

Oil on board, 8 × 10 inches

Collection of the artist

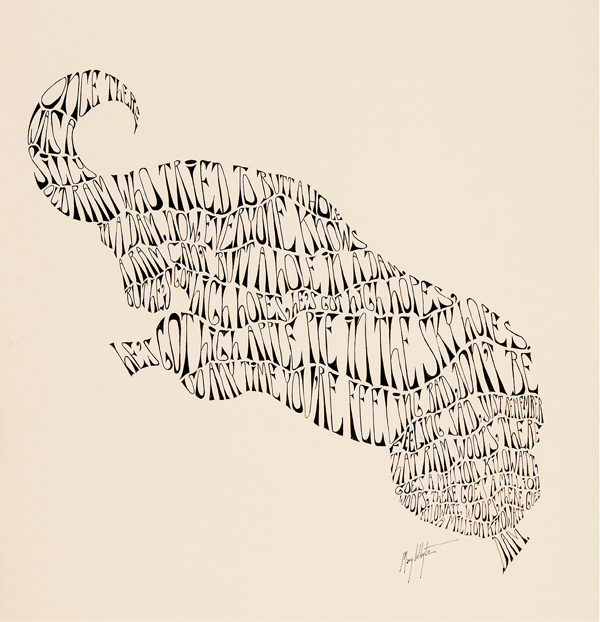

Drawn completely from her imagination, the setting is bucolic and shows a red barn, lotus blossoms, and a pond like those that surrounded her family home. Her first sale came as an eighth-grader. While visiting relatives in the resort town of Sea Girt, New Jersey, Whyte did a pen-and-ink sketch of a local inn. Her aunt presented the drawing to the innkeeper, negotiating a price of twenty dollars, which delighted the teenager. At age sixteen she did “word pictures,” many consisting of profiles of famous men; one was of Abraham Lincoln, within which she wrote the Gettysburg Address, and another cleverly used the lyrics “Once there was a silly old ram” from the popular 1950s song “High Hopes.”

For years Whyte made pen-and-ink studies that became the family's Christmas cards—a foretaste of her interest in seasons—and a tradition that she continued later in life with Paper Angel, a playful image of fresh young model.

During the summer of 1970, under the tutelage of her French teacher, she and fifteen classmates embarked on an eight-week trip to France and Switzerland. When he asked her if she knew the work of Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, she had to admit she had never heard of him. The trip opened her eyes to great art and architecture as well as to a cuisine and culture quite different from that of northeast Ohio. Her adept drawing of Paris documents some of her impressions of the foreign capital.

Like many young and promising artists, Whyte focused much of her energy on portraits of friends and family. She found that her older brother Tim was a willing sitter. Her sensitively handled drawing of him hints at her future skills as a draftsperson and her ability to capture a likeness. She later acknowledged that she probably sold only one of these early endeavors, but she learned a lifelong lesson. “I started painting people in watercolor when I was in high school. My first attempts were predictably muddy and overworked, but I was enthralled with both the power and delicacy of the medium. At the time I had no intention of being a portrait painter, but after I graduated from art school folks began asking me for paintings of their families. I soon discovered that I truly love painting people, and if someone was actually going to pay me to paint them, what could be better? It was like being paid to go to the amusement park.”

High Hopes Word Picture, 1970

Ink on paper, 12 × 15 inches

Collection of the artist

Christmas Card, 1969

Pen and ink on paper, 5 ¼ × 4 inches

Collection of the artist

Paper Angel, Christmas card, 2009

Watercolor, 23 ½ × 15 ½ inches

Private collection

Saint Michel, Paris, 1970

Graphite on paper, 9 ½ × 6 ½ inches

Collection of the artist

The first exhibition of Whyte's paintings and drawings took place at the Chagrin Valley Little Theater in 1973 and included a mix of still lifes, landscapes, and figure groups. The most notable painting was one done about fifteen miles from home in Burton, Ohio, the fourth-largest Amish community in the world. A sizable canvas rendered in a style reminiscent of Depression-era murals, the painting shows a scene of carriages and families on the historic village green. A large two-story building with a white porch serves as a backdrop. Horse-drawn buggies and a handful of plainly dressed people dominate a barren foreground, and a diagonal line of trees to the right creates the illusion of space. Because of its local history, a member of the community purchased it for one hundred dollars and placed it at the library in Bainbridge. Unfortunately the present location of the painting is unknown, although a photograph of the proud artist and crisp preparatory drawings record its visual power.

Tim, 1969

Graphite on paper, 14 ½ × 10 inches

Collection of the artist

Whyte continued to depict Amish scenes, precursors to her later work with the Gullah residents of Johns Island. Both groups represent cultures with deep historic roots and closely held religious beliefs. The Amish “plain people” forgo modernization, choosing to live simple, family-oriented lives without machines. They assiduously avoid the temptations—especially smoking, drinking, and promiscuity—of contemporary society. Their lives are regimented, even down to the design and color of their clothing. They eschew the use of tractors but are highly regarded for their agricultural skills and their rich farmland. “It wasn't the ‘quaintness’ of the Amish and the landscape that was inviting for me to paint…Here, I discovered, were people whose lives centered unswervingly around God and family, self-sufficient from the rest of the world. I wanted to capture as much as I could of it on paper, save it and protect it before it was changed and lost forever. I feared it was a community shrinking acre by acre and generation by generation as the modern world buffed up against it and frayed its corners.”

For Whyte, gaining access to the Amish presented its challenges, as photography was proscribed. She tells of one occasion when, after prowling around some fields, she set up her easel opposite a farmhouse and began to sketch. The family came home and promptly shut their curtains. Eventually a bearded patriarch came out and sat behind her, observing; gradually eight family members joined him and by doing so gave implicit permission for her to proceed. Their main concern was that she accurately portray the shape of their bonnets, the colors of their clothing, and the character of their beards.

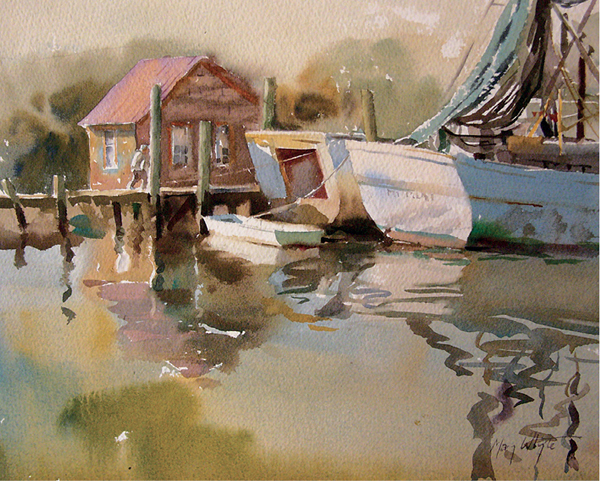

Although clearly talented and dedicated, Whyte had limited exposure to formal art education. As a high school student, she took a six-week class for adults with Florian Lawton (1921–2011), a northeast Ohio artist and member of the American Watercolor Society. From him she learned the importance of using quality materials, a lesson she continues to impart to her own students. When sixty of his paintings were exhibited at the Butler Institute of Art in 2009, his work was described glowingly: “A virtuoso in the watercolor medium, Lawton's flawless technique and romantic appreciation of his subject matter evoke a strong emotional resonance. His controlled washes of color and close observation of direct light reflect the influence of the best of the watercolor tradition, in particular the art of Winslow Homer, John Singer Sargent, and Andrew Wyeth.” Although Whyte does not remember that Lawton spoke specifically of these three artists during his class, she openly acknowledges that they have served as important touchstones for her own work and that Lawton was instrumental in teaching her about the possibilities of watercolor. Fortuitously, a high school boyfriend gave her a copy of David McCord's 1971 book on Wyeth, a now-dog-eared volume still cherished today with a place of honor in her studio. Bait Shack, her first finished watercolor, with its decrepit building and brown palette, demonstrates the impact that Wyeth's winter scenes had on the emerging artist.

Mary with Burton Amish scene

From the Chagrin Valley Times, June 28, 1973

Photograph by Bruce Krobusek

Amish Carriages, 1973

Graphite on paper, 17 × 13 ¾ inches

Collection of the artist

An Amish Barn, 1972

Graphite on paper, 12 × 17 ¾ inches

Collection of the artist

On announcing her intention to attend art school, Whyte encountered some initial resistance from her businessman-father, who declared, “I didn't raise you to be a goddamn hippie.” Determined, she planned to move out of the family home, get a job as a waitress, and, through the housing authority, find a place to live near the Cleveland Institute of Art. Because she was underage, she needed her father's permission to sign the lease; he relented about art school when he saw the disreputable location where she proposed to live, and he offered to assist her. She investigated various art schools; at the Rhode Island School of Design, she found students with spray-painted bodies making sculpture out of black plastic. Hoping for something more conventional, she enrolled in the Tyler School of Art, affiliated with Philadelphia's Temple University. In the early 1970s, Tyler had its own campus in the suburbs at Elkins Park, but it was sufficiently close to downtown that Whyte could easily enjoy the city's offerings. The school was known for its progressive curriculum, which included the liberal arts, but her instructors were largely cool to her traditional approach. “I did a still life with some of my mother's tea cups. My instructor asked why, and I said I liked looking at them. He said that was no reason.” Years later, as an established artist, she returned to paint the blue-and-white china set because she still loved its color and translucency.

Bait Shack, 1969

Watercolor on paper, 15 × 18 inches

Private collection

Shore Still Life, 1989

Watercolor on paper, 19 × 24 inches

Private collection

Because Whyte promised her father that she would get a teaching certificate—“something to fall back on”—she took some classes in acting and creative writing as well as one entitled catastrophic geology. Her concentration, however, was in art, with courses in drawing, graphic design, sculpture, and painting. A class in illustration inspired her to create her own children's book about a fat little whale who flies, part Dumbo and part Peter Pan. The story line is that the secret to flying is believing that you can. During her sophomore year Whyte drew a compelling self-portrait entitled Exploration, one of an ongoing series that shows her wearing an amazing hat.

She believes an elaborate hat and costume add a great deal to a self-portrait and intentionally deflect from the actual subject. In addition, this early self-portrait is rich in a variety of patterns and textures that can be found, for example, in her poncho and the cable-knit sweater behind her. Making notations in her sketchbook during a class with Roger Anliker, a famously strict painting instructor, Whyte copied down several meaningful phrases: “Painting is color, drawing is everything else,” and “The power to manipulate at will is the real strength of the artist.” Both maxims have served Whyte well in her own career.

Looking back on her experience at Tyler, she admits that she may have been something of a fish out of water: “I wish I could say there was a class or instructor I found particularly valuable, but the general atmosphere in art schools at that time (mid-1970s) was not favorable to representational art or classical training.” Most art schools had moved away from formal drawing classes and strict regimens, allowing students to go where they might. On occasion Whyte found her instructors' criticism somewhat harsh. Of her watercolor The Bucket, she was informed it was too Wyeth-like, despite its riot of rich greens.

She did enjoy her junior year in Rome, as part of the school's study-abroad program, and immersed herself in the culture, language, and gastronomy of the ancient city. While there she painted mostly landscapes. She was disappointed that there was so little interest in watercolor during her college years. “There was one watercolor class offered at Tyler, the year I studied in Rome. That was where the instructor said to me ‘Oh, I guess you know what you are doing,’ and offered no other advice or criticism the rest of the semester. Hardly considered a class, but it is on the record.” Despite the lack of instruction in her preferred medium, Whyte graduated cum laude in 1976 with a bachelor of fine arts and a teaching certificate.

Exploration, 1973

Graphite on paper, 27 × 19 ¾ inches

Collection of the artist

The first week at Tyler, Whyte, a willowy young woman, met Smith Coleman, a handsome young man from Dallas known to his friends as Smitty. They married in 1977 and have been artistic partners ever since, she as a painter and he as a talented frame maker. During art school, they explored Philadelphia's museums; they also made their way to Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, and the Brandywine River Museum, which had opened in 1971 and emphasized the work of N. C. Wyeth, his son Andrew, and noted American illustrators such as Howard Pyle. These experiences may have influenced her as much as her actual coursework at Tyler.

After graduation Whyte found employment in the field of graphic design; she did logos and advertising layouts on a freelance basis. Together she and Coleman ambitiously opened Studio Coleman, a gallery and frame shop over a tailor's business on Butler Pike in Ambler, Pennsylvania. Reflecting on this phase of her life, Whyte recalled, “A few years later, Henry J. Brusca, who would become one of our first true benefactors, came into the gallery and asked if we would like to move our small enterprise into his building—a restored house built in 1735 in Horsham, Pennsylvania. Henry had a beautiful antique shop of early American antiques on the first floor, and we put the gallery on the second floor. Smitty used the third-floor attic to do framing. Henry was like a father to us, and it is from him we learned to love antiques—as we often accompanied him to antique shows, setting up, decorating the booth, selling, etc. No one could pack a van better and tighter than Smitty. I swear he could put three houses of furniture into one van and still have room left over to swing a bat. Henry bought many paintings of mine, just to help us along so that we could pay the nominal rent. At the very first show opening I had at a gallery in Philadelphia, Henry, beaming with pride, presented me with a giant bouquet of red roses.”

The Bucket, 1972

Watercolor on paper, 14 × 18 ½ inches

Collection of the artist

Close-up of The Bucket

Smith Coleman and Mary Whyte, 1978

Photograph by Michael W. Heayn

Collection of the artist

Corky, 1977

Oil on canvas, 29 × 24 ½ inches

Private collection

Attempting to find her own voice, Whyte painted a variety of subjects during this period: portraits, pastoral landscapes, and some figure groups. The portraits were largely of women, and the opportunities came through word of mouth. They were the mainstay of her work at the time, averaging about two a month. Whyte has high standards for her portraits: “Anyone can do a good likeness. The thing is to paint a good painting, and one that will interest someone who does not know the person.” The likeness of Cordelia is proof of this statement. Unusual in its vertical format—selected to fit a frame the subject had bought in an antique shop—Cordelia appears as an affable and relaxed middle-aged woman. The image is enlivened by the stripes of her dress and the mix of cool and warm hues.

Cordelia, 1979

Oil on canvas, 25 × 15 inches

Private collection

Smith Bedford Coleman, Jr., 1990

Watercolor on paper, 20 ¼ × 16 inches

Private collection

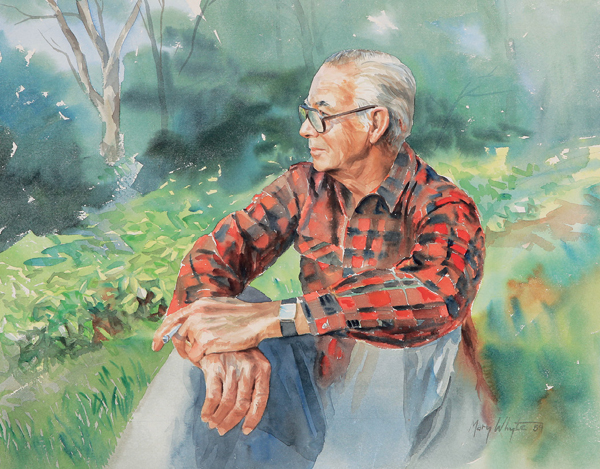

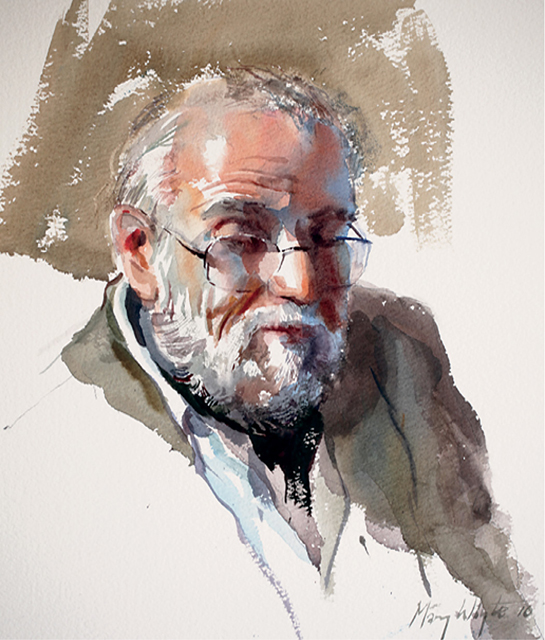

Other portraits by Whyte of bankers, university trustees, and suburban housewives are more formal and less intimate. One exceptionally endearing likeness, which was not a commissioned portrait, is the watercolor of the artist's father-in-law, Smith Bedford Coleman, Jr. The artist regarded him as a true and kind gentleman, a thoughtful man who took life at a leisurely pace. She painted him at ease and in nature in the front yard of her home. For Whyte scenery is less interesting than the human face, but she understands how important landscape is as a backdrop.

Early Spring Rabbits, 1978

Watercolor on paper, 16 × 22 inches

Private collection

Looking back, she has admitted that she was a bit at sea during this period: “I knew I wanted to paint, but didn't know what I wanted to express. For several years I painted a shopping list of subject matter: still lifes, landscapes, flowers, nudes, animals, and seascapes. Although most of the paintings found a home on someone's wall, none of them were truly aligned with my most passionate feelings, simply because I didn't know what those emotions were.”

Some of her forays had their humorous sides. In 1978 she did a series featuring rabbits—a subject immortalized by Albrecht Dürer—and, like his 1503 watercolor, Early Spring Rabbits is an intensely detailed and focused rendering. Whyte's, however, has a narrative element missing in Dürer's quasi-scientific approach. In order to study her subjects, an enterprising Whyte approached the owner of a pet store and asked if she could rent a rabbit for a short while. He obligingly agreed. She remembers that “for weeks I had some beautiful rabbits hopping around the studio, chewing on sketchbooks and light cords.”

Another project involving animals and her skills as an illustrator was a series of four interpretations of Noah's Ark, which she painted in watercolor and had reproduced as prints. All are ingenious and inventive, but the last one, which illustrates the ark landing with animals spilling out all over, is perhaps the wittiest. Instead of the canonic “two by two” the animals have reproduced heartily during their forty days at sea.

While Whyte was painting, her husband, Smith Coleman, was making frames for area artists and showing some of their work at the Horsham gallery, located not far from the noted impressionist art colony in Bucks County. One artist in particular, John Falter (1910–1982), became good friends with Coleman and Whyte. Falter was a successful illustrator with 185 Saturday Evening Post covers to his credit, more even than Norman Rockwell. Falter and his wife, Mary Elizabeth, frequently enjoyed picnics and parties with the younger couple and initially they did not realize Whyte was an aspiring artist. After a while she shyly admitted to him that she was a painter. Eager to nurture her talent, he paid her way to attend an oil painting workshop with figurative painter Jan De Ruth (1922–1991) in Ruidoso, New Mexico. Falter also gave her Gordon Hendricks's large volume on Winslow Homer, another source of inspiration.

Noah's Ark: The Landing, 1982

Lithograph, 20 × 19 ½ inches

Collection of the artist

The couples discussed Falter's specialty, the art of illustration, which was also well represented in the area by Howard Pyle and N. C. Wyeth, two masters of the discipline. This emphasis on narrative clearly affected Whyte, who relishes telling the stories behind the people in her paintings. Her major publications—Alfreda's World, Working South, and Down Bohicket Road—are substantially about her experiences meeting and getting to know her subjects. Falter's influence and Whyte's penchant for storytelling are further mirrored in her later success with illustrating children's books. In addition, the Falters served as role models who demonstrated that artists could have normal, healthy lives. “Looking back, if there was one artist who had directly influenced my life it would have been John Falter. He was the one who showed me that being an artist wasn't just about smooshing paint on a surface. From Falter I learned that being an artist meant fully experiencing this amazing and surprising world, and finding the artistic means to share what we have discovered with others.”

Following her workshop with De Ruth, Whyte painted a series of female nudes. She joined a group that drew from live models, but because she was a latecomer, she was assigned a position in the back row. Unhappy, she quit and hired her own models—including her housekeeper—to pose for her. She frequently enlivened her compositions with colorful textiles, as seen in Indian Blanket, where the figure stands dramatically and is vividly lit. The nudes were well received and sold well, although Whyte was dismayed when one gallery visitor referred to them as “bedroom art,” implying that the only place they could be hung was in a bedroom.

Indian Blanket, 1983

Oil on canvas, 45 × 34 inches

Private collection

Tired of apartment living, in 1983 Whyte and Coleman bought a house in Souderton, Pennsylvania, in the heart of Mennonite country. It was situated on a hill overlooking a stream and had a space with windows in the basement for her painting studio and another room for his photography work. They wanted to immerse themselves in the community and to experience a rural farming area. The surrounding landscape inspired The Good Earth, a large plein-air oil of a Mennonite farm.

Using a hefty easel that Falter had given her, Whyte dragged it to the same spot every day for a week. Its pastoral subject, complete with grazing cows, a tidy farmhouse, and silos, is reminiscent of John Constable's renderings of the English countryside. Cows were the focus of several sizable canvases, including a triptych, all of which tended to sell readily.

Ivy, 1979

Oil on canvas, 24 × 18 inches

Private collection

The Good Earth, 1990

Oil on canvas, 30 × 40 inches

Collection of the artist

More narrative than these paintings of scenery are her depictions of Jennifer Smith, a young girl whom Whyte first painted at age eight. Inveigling her to model by rewarding her with jelly donuts, the artist portrayed her lighting a pumpkin with a friend. With its nighttime setting, a pumpkin sitting on a post, and a view of a distant farm, it recalls similar paintings by N. C. Wyeth. For Whyte the activity conjured memories of her own childhood, as she wrote in a handout for a gallery exhibition: “I remember the October sky at dusk when everything had begun to turn to shadow and there was still just a touch of color left. I guess it was the only time we were allowed to play with matches.” According to Whyte, Jennifer was “the most patient of all my models; she never grows restless and is willing to work hour after hour.”

Lighting the Pumpkin, 1979

Oil on canvas, 20 × 30 inches

Private collection

Harvest Day, 1979

Oil on canvas, 36 × 36 inches

Private collection

In Harvest Day, Jennifer modeled for both girls sitting on a fence in a pastoral scene that resembles the work of Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Its lush landscape, the robust and rosy girls, and even the bonnet that obscures Jennifer's face connect with similar motifs in the French master's art.

The most visually powerful of the Jennifer series, Perchance to Dream, employs one of Whyte's favorite devices—a quilt with bright colors and patterns. The painting is also prophetic of her later work with the Gullah people.

Extending her earlier fascination with the Amish, Whyte painted Wash Day, also notable for its use of colorful quilts. She successfully labored to capture the sense of wind, a visual concept that may have been inspired by Winslow Homer.

Recognition came her way in 1984, when the organizers of the Philadelphia Art Show selected Figure Eights for their poster. In devising this composition, Whyte hired local models and made a mock-up of a billowing skirt, which she stuffed with tissue to hold its shape. Despite these efforts, Whyte later realized some inaccuracies: “The figures were from some old photos and my imagination—I did manage to get the skating form wrong, and incorrectly depicted one of the skaters executing a tight circle on the outside leg.” Like her earlier Amish subjects, the skaters are wholesome youths, enjoying the outdoors and physical activity. There is a certain timeless quality to the image, which is reinforced by the generalized setting—a frozen pond somewhere. The depiction is also reminiscent of N. C. Wyeth's classic painting for the cover of Mary Mapes Dodge's Hans Brinker; or, the Silver Skates. Whyte's canvas appealed so much to a woman with five daughters that she purchased it.

Perchance to Dream, 1984

Oil on canvas, 41 × 50 inches

Private collection

Wash Day, 1985

Oil on canvas, 16 × 24 inches

Private collection

Two years later Whyte embarked on a series dedicated to the twelve months, which was part of a solo show at the Allerbescht Gallery in Telford, Pennsylvania. She explored seasonal changes to the landscape and corresponding activities—an approach that she continued later in her career. Whyte felt it would challenge her to develop a thematic thread; she also believed the set of twelve watercolors would make an engaging exhibition as they all featured children. And it did. “If I heard it once, I heard it fifty times, someone saying ‘Oh, that looks like my child when he was that age.’ I think that's a fine compliment that they can relate to a painting that much.”

Winslow Homer, 1836–1910

Fresh Air, 1878

Watercolor with opaque white highlights over charcoal on cream,

moderately thick, rough-textured wove paper, 20 1/6 × 14 inches

Brooklyn Museum, Dick S. Ramsay Fund, 41.1087

Figure Eights, 1984

Oil on canvas, 23 × 38 inches

Private collection

March, 1987

Watercolor on paper, 20 ¾ × 27 ¼ inches

Collection of the artist

January is illustrated by crack the whip—a game immortalized by Homer—and the subject of February is tobogganing. A boy in an inner tube epitomizes August while December is represented by a girl feeding birds. The depiction of March evolved out of a portrait commission; Whyte had met a couple while skiing in Montana, and they asked her to paint their son. She went to Indianapolis to do the young man's portrait, and, after it was completed, she asked him to pose for her. She made a kite tail to represent the arrival of spring and painted his profile against a hazy green Pennsylvania landscape.

This methodology of combining elements from different sources—rather than strictly adhering to a realist agenda—became Whyte's modus operandi. She admits that she happily alters details and adds props, contending it is more important to catch the feeling of the moment than to be absolutely accurate. In an interview section of her instructional DVD, she admits: “Of all my paintings not one of them is something that is exactly as I saw it, but is of course exactly what I felt…. I invent lots of stuff; I bring in objects that I feel somehow will promote the feeling or the objective that I have for the painting. I don't hesitate to change the color of a dress, the line of a chair, or bring another object into the painting that will help the message or the overall emotion of the painting.”

During her years near Philadelphia, Whyte's artistic energy was expended by heading in different directions. While she had considerable sales of portraits, nudes, and landscapes, Studio Coleman was not an overwhelming success, perhaps because many prospective clients gravitated toward New York City for their art purchases. This, plus Whyte's bout with cancer and an ensuing regimen of chemotherapy, convinced the couple that after almost two decades in the area, it was time for a change of venue. In Alfreda's World, she acknowledged, “We knew that we had to move to a place that would give us deeper meaning to our lives—a place where we could reinvent ourselves and start over.” Through friends they had been introduced to the Charleston area and had vacationed there on several occasions, so in 1991 they took the plunge and bought a house on Seabrook Island. They were enamored by the quiet, the gentleness of the sea air, and the poetry of the Spanish moss that hangs from live oak trees. “What resulted from that move would, for us, change the focus and direction of everything.”

Black on Whyte, 1982

Oil on canvas, 36 × 28 inches

Collection of the artist

Dunes, 2011

Watercolor on paper, 12 × 9 inches

Private collection

The Homecoming, 1992

Watercolor on paper, 25 × 20 ½ inches

Private collection

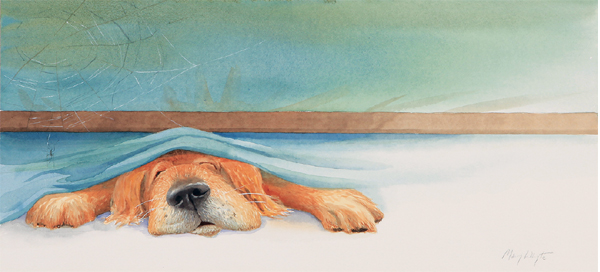

One of Whyte and Coleman's first guests in their new home was a friend from Ohio, Constance McGeorge, a teacher who had taken one of Whyte's workshops. When her visitor asked how the move went, Whyte replied, through the eyes of their golden retriever, Boomer: “confusion, disruption, disorientation.” From this conversation emerged Boomer's Big Day, a happy collaboration that thrust Whyte into the world of illustrating children's picture books. The introductory synopsis captures the dog's sentiments: “Boomer's ready for his morning walk. Here's his leash. There's the door. But try as he might, he can't get anyone to pay attention to him. The humans in the house don't rush out the door after breakfast as they normally do. And, most confusing of all, strangers arrive to pack all the things in Boomer's house into boxes. There's definitely something unusual going on.” Finding himself confused, Boomer searches for his tennis ball under a bed, his large nose almost a caricature. Another scene captures the chaos he experiences; shown from above with boxes everywhere, it features a colorful quilt on the bed. The next two pages are in direct contrast: blank, except for a recumbent Boomer and the words “Before Boomer knew it, the house was empty.” But after a long road trip in a crowded car, Boomer, like his owners, makes the adjustment to life at Seabrook Island and learns to love walks on the beach.

Boomer under the Bed, from Boomer's Big Day, 1994

Watercolor on paper, 9 × 19 ½ inches

Collection of the artist

Whyte put her considerable skills to work and came to understand fully the parameters of picture books, such as avoiding the gutter, planning space for the text, and keeping the visuals as simple as the story. Her mentor, John Falter, and their numerous discussions about Howard Pyle and N. C. Wyeth prepared her well for this kind of work. The images of Boomer racing across the page are enchanting, his facial expressions delightful, and his body language totally in character. The openness of Whyte's watercolor brushwork and the light palette make for fresh and engaging images. Boomer's Big Day was followed by two other books featuring him as the protagonist: Boomer Goes to School and Boomer's Big Surprise. In the former his daffy personality overflows as he enjoys a day at school spent playing with the children and disrupting the classroom. In the latter the storyline is more moralistic: Boomer is forced to share the stage with a young puppy, whom he finally befriends after much consternation.

Chronicle Books accepted McGeorge and Whyte's first book, and Whyte recalls how “it was like we had won the lottery, and we had a ball doing the story and the next several books. We agreed to do a book a year together as long as it was fun—and it was, for a good ten years.” McGeorge mirrors Whyte's sentiment and remembers their collaboration as “a blast—I can't call it work.” Together they set Waltz of the Scarecrows in the kind of farm country familiar from their childhoods in Ohio.

The young girl resembles the artist when she was a youth and the grandparents are modeled on neighbors from Seabrook Island; other friends dressed up and waltzed for the artist so that she could photograph them. Whyte depicts herself in several scenes, including the illustration “Harvest Ball,” because, as she explains, “I needed another model in a hurry.” The scarecrow concept inspired an unusual self-portrait, where Whyte dons the fanciful hat she is shown wearing in the childen's book. However, its playfulness and vibrant color belie this interpretation; the likeness is another instance of the artist dressing herself up in a manner that deflects from too much self-examination.

For Chestnut, McGeorge and Whyte moved from rural Ohio to South Carolina for the setting. They walked the streets of historic Charleston, planning a route for their central character—a hardworking, loyal, and clever horse who saves the day while his owner sleeps; he successfully makes all the deliveries on time so that a birthday party for the mayor's daughter can move forward. The storyline permitted Whyte to paint such well-known structures as the Exchange Building and St. Michael's Church as part of the backdrop. A double spread shows a delightful aerial view of the city, dotted with red rooftops.

Harvest Ball, from Waltz of the Scarecrows, 1998

Watercolor on paper, 17 ¾ × 27 inches

Collection of the artist

Scarecrow Self-portrait, 1999

Watercolor on paper, 29 × 20

Private collection

Cover for Chestnut, 2004

Watercolor on paper, 12 ½ × 10 ½ inches

Private collection

Before abandoning children's books altogether, however, Whyte illustrated three books for a Japanese publishing house, an interesting experience that included an all-expense-paid trip to Japan. She found the firm's approach to be didactic, with a tendency toward books about feelings and manners, with much less fantasy. In a spread for The Color of Sky a boy wears a distinctly American polo shirt under a Japanesque sky made from simple, bold colors and origami shapes. On the left is space for the Japanese text under which the following is scrolled: “Listening to someone's story may lead to understanding.”

Like the nearby city of Charleston, Seabrook Island is steeped in history; two 2,000-acre plantations there used slave labor to grow Sea Island cotton, and later, in the early 1900s, sportsmen came for hunting and fishing. Around 1950 the Episcopal Diocese of South Carolina acquired 300 acres for a retreat and camp for children, and in 1970 private developers purchased 1,100 acres for a residential community with a golf course and equestrian center. Along with its neighbor Kiawah Island, Seabrook has attracted retirees, vacationing families, and second-home owners. To get to the islands, one traverses Johns Island along Bohicket Road—a study in contrasts: former plantations, small cinder-block homes, and flashy fast-food restaurants and convenience stores.

A canopy of centuries-old live oaks swathed in Spanish moss provides a rhythmic alternation of sunlight and shadow, and each tree is marked with a bold yellow-and-black striped sign to ward off motorists. Bohicket Road is the “connecting thread” that links the artist's world on Seabrook Island to another older, colorful, and evocative tradition. It is here that Whyte found inspiration—in the landscape, the people, and in a culture very different from her own.

Initially Whyte expected she would paint the countryside of her adopted home, as she did in Cows and Sunflowers, a transitional canvas that is a pastiche of Pennsylvania livestock and South Carolina vegetation. She also thought she might be doing a few commissioned portraits of white children, such as Andrew, but this was not to be.

Shortly after her arrival she agreed to teach a workshop. Finding herself in need of models, she looked to the Hebron Saint Francis Senior Center on Bohicket Road. In a South Carolina Educational Television interview on National Public Radio she described her experience: “Here I was, a little Yankee girl wandering into this church one day, and they literally embraced me and invited me back and truly changed my life and the direction of my whole painting career, and little did I know that over the next twenty years I would be doing dozens and dozens of paintings of these women, their children, and their grandchildren.”

Listening to Someone's Story, from The Color of Sky, 2003

Watercolor on paper, 11 × 17 ½ inches

Collection of the artist

Down Bohicket Road, 2011

Watercolor on paper, 21 ¾ × 18 ¾ inches

Private collection

Cows and Sunflowers, 1996

Oil on canvas, 23 ½ × 35 ½ inches

Private collection

When pressed by the interviewer, University of South Carolina history professor Walter Edgar, Whyte admitted that she could never explain why this community opened their arms to her, not only a white woman artist but also a true outsider. “I'm really from off,” she told him. After living in the South for two decades, the artist views the fact that she is an interloper as a distinct advantage.

Andrew, 1992

Watercolor on paper, 24 × 19 inches

Private collection

New Book, 2008

Watercolor on paper, 13 ½ × 13 ½ inches

Private collection

Twirl, 2011

Watercolor, 18 ½ × 18 ½ inches

Private collection

Cool Breeze, 2003

Watercolor on paper, 47 ½ × 39 ⅛ inches

Private collection

Not burdened by the legacy of slavery and prejudice in the same way that her artistic predcessor, Elizabeth O'Neill Verner, was, Whyte can more easily see the humanity in all people. Verner had emerged in the 1920s as one of the leading figures of the Charleston Renaissance, a movement that helped to bring about the economic, artistic, and cultural renewal of lowcountry South Carolina. The renaissance and preservation of old Charleston—promoted then as America's most historic city—were fueled by a coalition of artists, writers, preservationists, and a few politicians. Verner, through her numerous etchings of street scenes and architectural gems, her pastels of flower vendors, and her copiously illustrated books, developed a following among an ever-increasing number of tourists. Because her clientele was largely from the North and the Midwest, she provided them with the kind of imagery they expected. When it came to Verner's portrayals of African Americans, that meant quaint depictions that verge on caricature. Her popular pastels, such as Flowers Ma'am?, focused on the women who sold their flowers and baskets at the city's major intersections. In fact, when these women were threatened with a new ordinance that would prohibit their activities, Verner came to their rescue, arguing “that Charleston had more free advertisement in nationally known magazines than any other city in the country and that in every picture a flower woman was strategically placed to give local color.” Even Verner's rival, Alfred Hutty—a Midwesterner like Whyte—freely exaggerated facial features and postures in his depictions of African Americans.

Close-up of Cool Breeze

Guardian Angel, 2006

Watercolor on paper, 21 × 28 inches

Private collection

Mary Whyte, on the other hand, has transcended the biases of her upbringing, and her more tolerant patrons lack the narrow-minded expectations of Verner's and Hutty's. She says of their work, “They are caricatures and stereotypes and weren't of real, true, honest people…. That was an era, a document of those times.” While there is a nostalgic element in Whyte's work, it is not sentimental; rather, it celebrates and preserves particular lifestyles. She sees a comforting analogy with the Amish people she knew as a teenager who, like the residents of Bohicket Road, are close to the land, family-centered, and religious.

Elizabeth O'Neill Verner, 1883–1979

Flowers Ma'am?, circa 1940

Pastel on silk, 15 ¼ × 11 ½ inches

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Leonard L. Long, Jr., Charleston, S.C.

At the Hebron Center, which she attends almost weekly, Whyte found warmth and solace and an introduction to Gullah customs, language, and cooking. On that first day, she encountered the women busy in the kitchen, and after one look at her—tall, thin, and white—they immediately determined their mission was to put “meat on her bones.” They offered her a plate piled high with fried fish, macaroni and cheese, red rice, collard greens, and cornbread. The artist ate with relish. The first to welcome her, embrace her, and feed her was Alfreda Gibbs Smiley LaBoard.

Church Picnic, 2010

Watercolor on paper, 4 ⅞ × 6 inches

Private collection

Soon the older black woman became her good friend and artistic muse. Later, during an interview for a television documentary, Alfreda recalled their first meeting: “The first time Miss Mary come to the center, we were there sewing and cooking, and in walk this white girl, kind of scraggly an’ all…. Here was this skinny, kind of pitiful white girl comin’ in, not knowin’ where she was goin’ or what she was looking for, and definitely in need of some love. So the first thing we do is we give her a big plate of food. You know, to fatten her up a bit. God know I been tryin’ to fatten her up for years, but it still not workin’…. So I keep feedin’ her and lovin’ her because it what she need. It what everybody need.” In addition to sustenance and love, Alfreda unknowingly set a new course for Whyte's paintings.

Usually about fifteen women congregate weekly at the center to pray, sing, socialize, quilt, and eat. Descendants of slaves who had labored on area plantations, they tenaciously hold on to their Gullah culture, an amalgam of African, Jamaican Creole, and Barbadian dialects blended with English, and manifested not only in linguistics but also in crafts, agriculture, superstitions, religion, and cooking. As they go about their various activities, and while they share their triumphs and tribulations, Whyte sketches them. She also regularly joins in: she cuts squares for the quilts, threads needles, helps clean up, and, on special days, passes out bingo cards. She has earned their trust and respect, and they—and their children and grandchildren—have become willing models for her work. Her paintings reflect mutual warm feelings. When asked the challenging question, “Why do you paint African Americans?,” she responds: “Because I want to paint. Because I want to feel. Because I once thought I would never make it to my fortieth birthday, and I want to experience every little bit of gritty sand, pungent smell, and cock-eyed smile this amazing life has to offer.”

Whyte was deeply enriched by her friendship with Alfreda, who at the weekly gatherings gave informal talks on life's lessons, sometimes scolding, sometimes cheerleading. Alfreda had raised many children and grandchildren, assuming a role not unlike her grandmother's, the island's midwife and herbalist. Alfreda had grown up nearby on a Wadmalaw Island plantation, where she and her family did the backbreaking work of picking crops.

Whyte, hoping Alfreda would record some of her memories for her offspring, gave the older woman a notebook, but somehow she never found time to write them down. One day they drove over to see Alfreda's childhood home, and Whyte recorded her own reactions: “This place wasn't lushly overgrown with the forgiveness of time like so many parts of the island, but submissive and dusty under the beating sun…. We finally pulled up in front of a tiny peeling gray shack. The front door yawned open, revealing bare floorboards and a sunless interior. A massive oak tree shielded the house from direct sun, but hadn't quite kept out all the harshness of the past.” The site was filled with memories good and bad, of hard times and of love, of enslaved ancestors and more recent victims of lynching. The tree had its own symbolism, as Whyte recounts: “[Alfreda] had once told me about a tree, a tree where several of the islanders had paid their final debts to the plantation owner. She did not witness this herself, but her mother had.”

Hebron Church, 2011

Watercolor on paper, 11 × 13 inches

Private collection

Alfreda, 2001

Watercolor on paper, 15 × 13 inches

Private collection

Lipstick, 2003

Watercolor on paper, 20 ⅛ × 20 ⅛ inches

Private collection

Sunday Dinner, 2001

Watercolor on paper, 22 × 19 inches

Private collection

Wednesday Chores, 2004

Watercolor on paper, 38 × 28 ½ inches

Private collection

Sliced Apples, 1999

Watercolor on paper, 27 × 21 inches

Private collection

Finishing the Quilt, 2008

Watercolor on paper, 19 × 17 ½ inches

Private collection

Alfreda, 2012

Graphite on paper, 15 × 11 inches

Private collection

Dayclean, 1998

Watercolor on paper, 14 × 16 inches

Private collection

Alfreda had stories to tell that gave the artist great pleasure and poignant insights. One day when Whyte visited Alfreda at her simple home, Whyte wondered about a certain sweater her friend was wearing, an olive-colored cardigan with colorful patches on it. Alfreda explained that after Hurricane Hugo had devastated Johns Island and the surrounding area, her church had received several boxes of clothing. One held brand-new sweaters that had intentionally been cut so that they could not be resold. When the artist expressed dismay, Alfreda said: “Child, you best be getting over that one. Every time someone do you wrong, you can't keep goin’ on about it. And you can't be worrying about what other people have, either. People always worryin’ about someone else got more than them. None of this belong to us anyway…. It's God's. All this belong to God. Everything. Even this raggedy ol’ sweater. It ain't really Freda's sweater. No ma'am. It belong to God. I just taking care of it for him.” Ever resourceful and upbeat, Alfreda covered the holes with patches decorated with flowers, “Flowers, just like the Garden of Eden,” she explained.

The Hugo Sweater is a powerful tribute to the indomitable spirit of the artist's friend. In the painting Alfreda's robust figure looms in the foreground silhouetted against a wall with peeling pale-blue paint. Her large scale is exaggerated by the worm's-eye perspective and by her embrace of an oversized bunch of collards. The composition exudes a sense of grandeur that elevates mundane and quotidian details to an ennobling humanity. For a long while Alfreda LaBoard was the artist's primary model and dearest friend, and, in gratitude for their friendship, the artist was often generous and lent a helping hand to the matriarch and her family.

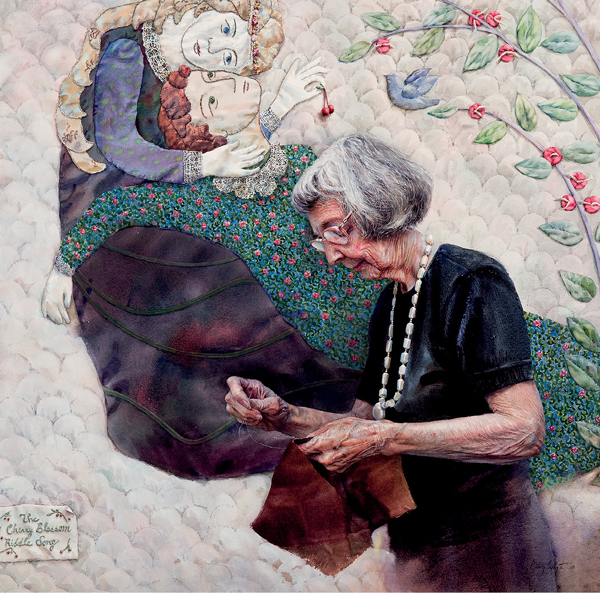

The focus of the Hebron group is the making of quilts—an age-old craft with roots in Africa. Quilts are metaphors, as the artist has explained, “We are like scraps of fabric: some are beautiful, and some are torn; some are colorful, and some are faded. Each piece of fabric is unique, and not particularly useful by itself. It is only when we stitch the pieces together side by side that we have a complete quilt. Only when every piece touches the others is the quilt finished and beautiful and whole.”

The quilts also have an important purpose: they are sold to raise money for the senior center and the church, a historic white-frame structure that had been built by former slaves shortly after the Civil War. Much of the wood had come from a shipment of timber that had shipwrecked near the mouth of the Edisto River. The church's simple yet classic design was modeled on the more substantial and upscale Johns Island Presbyterian Church further inland on Bohicket Road. Just like the Hugo sweater, the practical reusing of available materials produced a serviceable structure for island residents. Similarly, much of the fabric for the quilts comes from property owners of Kiawah and Seabrook who regularly rid their closets of passé designer clothing.

Whyte knows and greatly appreciates quilts and has a fine collection from her husband's family neatly folded in a pie safe in her kitchen. For her these lovingly crafted objects serve as important components of her paintings, both thematically and visually. Her interest in them predates her arrival in South Carolina, as exemplified by such paintings as Perchance to Dream (page 78). Seventeen years later Whyte returned to the theme of a young girl dozing in Dream of the Ancestors.

The Hugo Sweater, 1997

Watercolor on paper, 23 × 24 inches

Private collection

Mama's Chores, 2003

Watercolor on paper, 20 ¾ × 29 ½ inches

Private collection

Lilly Sleeping, 2003

Watercolor on paper, 26 × 21 inches

Private collection

Here Dejonna, placed frontally and closer to the picture plane, is shown enveloped in a colorful quilt and highlighted by a warm light. The viewer can only wonder about her dreams: Are they of Africa? Slavery? Or, possibly, she dreams of her nurturing and loving great-great-grandmother who made this soft wrap. Whyte uses quilts as part of the narrative: the act of sewing them, indoors and out, airing them, and ironing them. They serve as both background and foreground elements. Quilts also have an emblematic quality: they are the connective fiber of the Hebron group and link one generation with another.

In Whyte's book Alfreda's World, fourteen of the thirty-seven paintings illustrated include a quilt. The second-most-frequent topic is cooking, with six illustrations, a reflection of the group's passion for food and the physical and spiritual nourishment it provides. The quilts supply Whyte with color, pattern, and texture, while cooking allows her to employ two of her favorite devices: smoke and steam. It is her masterful facility with watercolor that permits Whyte to simulate the effects of rising vapors.

Close-up of Lilly Sleeping

Dream of the Ancestors, 2001

Watercolor on paper, 21 × 21 inches

The Wright Southern Collection

Jubilation, 2005

Watercolor on paper, 20 × 29 inches

Private collection

Typically Whyte begins her compositions by painting the background with the broadest brush feasible. She has already worked out how she will arrange things through numerous pencil sketches—anywhere from three to twenty-five—and watercolor studies. For steam she tips her paper and floods it with water, then quickly lays down a swath of one color. Before it dries she goes back in and overlays it with another, keeping her surface very moist and blotting it with a paper towel if it gets too wet. She labors to keep everything fluid until she gets the effect she desires, often leaving passages of paper untouched. If the pigment gets too dry, she resorts to certain tricks for wetting the edges of a color area and making them bleed ever so slightly.

In Sister Heyward, for instance, almost one-third of the painting is dedicated to the steam that makes its way upward diagonally from the pot, framing and setting off Georgeanna Heyward's determined face. The steam curves and winds and becomes an essay in abstraction while the white curtain blows in the wind and forms a more geometric shape. Almost a jarring interruption is the realistically rendered hook which hangs down directly over her hand—a spooky element reminiscent of Andrew Wyeth's portraits of his friend and neighbor Karl Kuerner. The hook, however, is very subtle and does not distract from the focal point, which is Georgeanna's profile. Whyte elucidates her method in her carefully constructed how-to book Painting Portraits and Figures in Watercolor: “Although the soft edge of the steam is appealing, the eye will always be more attracted to a hard edge.”

Sister Heyward is also a superb example of Whyte's ability to paint the skin of African Americans, here illuminated so beautifully as the model turns to the light. This skill, which Whyte has labored to perfect since her move to South Carolina, has become an artistic hallmark. Her portraits of Alfreda, decked out in one of her Sunday hats, are further testament, as are her numerous paintings featuring her model Tesha. Whyte explains that there are many variables in painting skin tone, including lighting, surrounding color, and what the individual is wearing. Also, flesh—whether black or white—is not all one color: “Everyone's skin color has a predominance of red, yellow, or blue, which explains why we look better in certain colors…. Within the face's overall coloration there are always a myriad of interesting, nuanced colors. Many people have more ruddiness to the fleshier cheek and nose area and more violet tones in the areas of thinner skin, such as around the brow and eye area. Generally there is a cooler color beneath the nose around the mouth, particularly for men, who have a shadow of a beard.”

Sister Heyward, 2001

Watercolor on paper, 27 ¾ × 18 ¾ inches

Private collection

One of Whyte's favorite paintings by Andrew Wyeth is The Liberal, which clearly demonstrates how he layered and juxtaposed a variety of colors to create the sense of a ruddy complexion. Like the topknot depicted in The Liberal, the hats in both Alfreda (page 106) and Red (page 3) set off the face by virtue of the colors and their sculptural shapes.

Georgeanna Heyward and other women in the quilting group have served as engaging models. The matriarch at the Hebron Center was Mariah Taylor, age ninety-six and described by the artist as having “a regal bearing that was breathtaking.” Mariah was one of the first of the quilters Whyte depicted, in a lively painting called Queen.

Andrew Wyeth, 1917–2009

The Liberal, 1993

Watercolor on paper, 16 ¾ × 23 ¼ inches

Collection of the Greenville County Museum of Art, Gift of Chicken and

Hurdle Lea, Tom and Susan O'Hanlan, and Jan and Glenn Spears

The Liberal, 1993 drybrush watercolor © Andrew Wyeth

The foreground is dominated by a multicolored quilt that Whyte herself purchased. Twenty years later, in Down Bohicket Road, the artist conceded, “I had no idea at the time [1992] that this one painting would be the catalyst for a body of work that would have such an impact on my life and career.” The composition is carefully worked out so that the diagonals of the quilt, with the foreground part out of focus, lead the eye to the main points of interest—Mariah's face and hands. The background is enlivened with the horizontals of the curtain, chair, and slats, which are thoroughly balanced by the verticals of chairs, window moldings, and picture frames. Despite all the visual information and details of clothing, it is nevertheless Mariah's personality that radiates throughout.

Orange Hat, 2004

Watercolor on paper, 17 ¾ × 18 ¾ inches

Private collection

Bean Soup, 2006

Watercolor on paper, 38 ½ × 28 inches

Private collection

Queen, 1992

Watercolor on paper, 26 × 20 inches

Private collection

Sing unto the Lord a New Song, 1992

Watercolor on paper, 26 × 30 inches

Private collection

Many artists over the centuries—Rembrandt, for example—have proclaimed that older sitters are more interesting than youthful ones; the common explanation is that their life experiences are reflected on their faces. Mariah, thinner than many of the other women, had an unusually expressive face, and, when wearing her eyeglasses on the end of her nose or her old straw hat cockeyed on her head, she lent herself to quasi-caricature. The sentiment of such paintings as Sing unto the Lord a New Song is reminiscent of some of Elizabeth O'Neill Verner's flower vendors.

Mariah, born in the first decade of the twentieth century, would have witnessed and known women like the one portrayed in Flowers Ma'am? (page 102). In her story about Mariah and the visit to her house to sketch her, Whyte has recounted how Mariah sat patiently for the artist, passing the time by singing her favorite hymn. When the sketch was complete, Whyte showed it to her model, who responded with great surprise. “Wha-ha-ha! Is da’ me?…I ne'er saw me look like da’!…Praise Jesus!” Mariah then touched the back of her head, working her fingers over the narrow braid there, which she had rarely seen, even in a mirror. When Mariah passed away, Whyte was one of only three white people in attendance at her funeral. Before the service began, all three were led to the front of the church, close to the casket. When Whyte inquired why they were so positioned, it was explained: “In Mariah's time, it was considered an honor to have a white person at a funeral. And the more honored you are, the closer you sit to the deceased.”

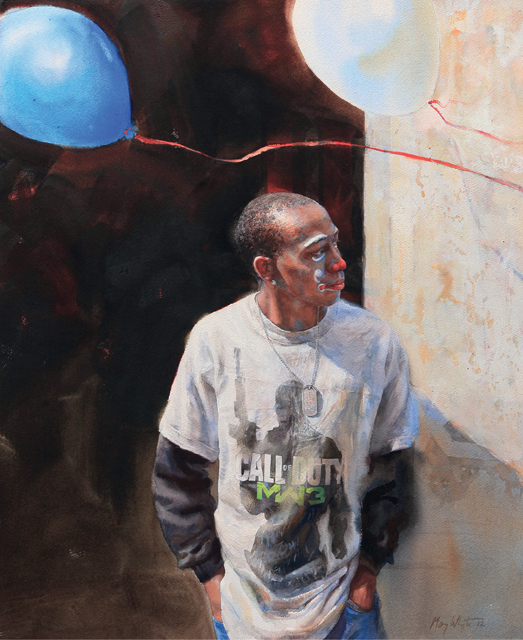

Other members of the Hebron Center's extended family—children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren—soon became Whyte's models, offering a different sensibility to her paintings.

While the older women actively labor at their quilts, in the kitchen, or in their yards with clotheslines or crops, the young models typify a more playful and leisurely mood. Whyte asserts “working with children as models can be great fun. While the little ones get wiggly at times, I have found that in many ways they are easier to paint than adults. Children are rarely concerned with their hair or attire…. Most children are delighted to be the center of attention.” Among the youngest and most winsome are the subjects of Inchworm and Black-eyed Susan.

Both girls are engaged in something that they hold in their slightly pudgy fingers, but beyond that there are few similarities. The honey-colored girl in Inchworm is placed in the lower right quadrant of a vertical composition and faces into the sun, which illuminates her brow and casts pale-blue shadows on her white dress. The viewer's eye as it moves from left to right is naturally led to her, surrounded as she is by a large and bending stand of sunflowers. These are rendered in a general sort of way with fluid brushwork so as not to distract from the main point of interest. The endearing model in Black-eyed Susan stands at the center of the painting and looks directly out at the viewer with a hint of surprise on her face. The devices that frame her are a window molding in the upper left and a quilt with diagonal strips sewn into squares. The off-white clapboards of an old house further serve to set off the model, while the black-eyed susans behind her relate directly to the pattern in her dress. The narrative element in Black-eyed Susan is stronger, as there is the suggestion that the youngster has picked a forbidden flower and has been caught in the act.

Pinwheel, 2007

Watercolor on paper, 21 ¾ × 28 ½ inches

Private collection

Inchworm, 2001

Watercolor on paper, 28 ⅞ × 19 inches

Private collection

Props are integral to Whyte's depiction of children and often include some of the artist's favorite flowers. In Lilly the young model smilingly offers an oversized pot of the plant for which she was named. As in Inchworm, the figure is placed in the lower right, but here she is turned toward the viewer, and the flowers project forward. The darker leaves echo the shape of Lilly's braids, and the absence of background detail leads the viewer's eye toward her.

Black-eyed Susan, 1999

Watercolor on paper, 21 × 21 inches

Private collection

Lilly, 2003

Watercolor on paper, 29 × 21 ¾ inches

Private collection

Umbrellas are another hallmark of Whyte's portrayals of young people. They were also favored by her idol John Singer Sargent. In his 1911 watercolor Simplon Pass: Reading, the brilliant turquoise and purple of the parasols are reflected in the sitters’ clothing. While Sargent's models customarily used parasols to protect themselves from the sun, Whyte's young girls seem less familiar with the objects they are holding.

In Yellow Umbrella and Red Umbrella, the shape and color of the object are critical. In the former the umbrella is better defined, with several spokes visible, as it embraces her in its sunny warmth. She faces into the bright light, which illuminates her ruddy complexion as well as the pale and delicate flesh of her chest. The painting is a portrait of the granddaughter of friends and is more concrete than Red Umbrella, in which the upper expanse of the umbrella is largely suggested. Red Umbrella has a stronger narrative: it is clearly raining, and Lilly turns her face forward, wistfully engaging the viewer, as if saddened by the inclement weather. In addition, she is closer to the picture plane, and the crisp handling of her face stands in contrast to the abstracted background.

Color is key in both of these paintings, as it is in almost all instances. Whyte noted in Painting Portraits and Figures in Watercolor: “Color helps to create the illusion of form and the space around form. It also has the ability to shape our mood and influence our senses. The feeling that we get when we look at a portrait made with cool neutrals can be very different than when we view a portrait comprising oranges and yellows. One painting may signify a person with a somber or serene temperament, while another color palette may suggest a robust, vibrant personality.”

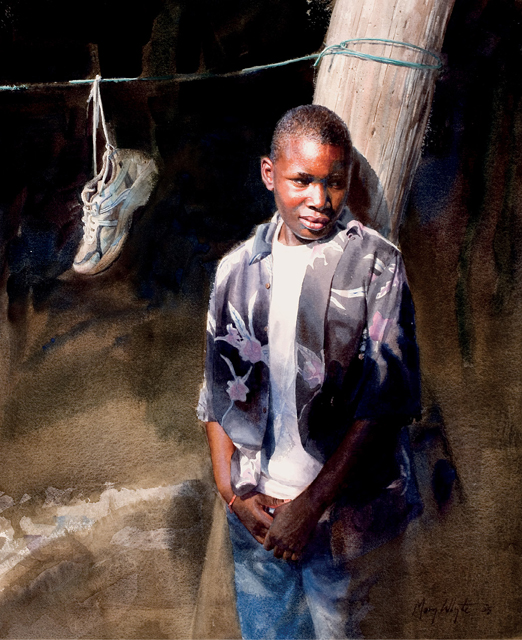

Sneaker and Acorn are very different from the umbrella paintings; the models are older, less automatically appealing, and the colors have shifted to deeper earth tones. Moodiness pervades both watercolors, derived in large part from the setting, and both are reminiscent of the art of Andrew Wyeth, often criticized for his somber palette. Whyte first encountered Wyeth's work in high school through reproductions in a monograph. Later, while in art school, she saw actual paintings by him at the Brandywine River Museum. But it was not until she saw his paintings at the Greenville County Museum of Art in the late 1990s that she “understood how dark they get and how much more powerful you can get things with cool light and warm shadow.” The historic and typical application of the medium is transparent and light-filled, as one finds in most watercolors by Homer and Sargent, the first painters to elevate the medium to a level equivalent to oils and pastels. Although Wyeth did use black from time to time, more often he achieved dark tonalities through the mixture of such colors as green and burnt sienna. “Cool light and warm shadow” is a hallmark of Whyte's technique, one she tries to share with her students.

John Singer Sargent, 1856–1925

Simplon Pass: Reading, 1911

Transparent and opaque watercolor over graphite, with wax resist, 20 × 14 inches

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Hayden Collection, Charles Henry Hayden Fund, 12.214

Photograph © 2013 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Yellow Umbrella, 2010

Watercolor on paper, 14 × 12 inches

Private collection

Red Umbrella, 2005

Watercolor on paper, 14 ½ × 14 ½ inches

Private collection

Close-up of Red Umbrella