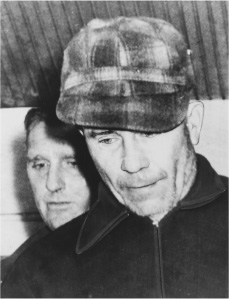

Gein (foreground) after his arrest

In the midnight hours of a summer evening in 1952, a radiant full moon shone down on Plainfield, Wisconsin, a small, tranquil farming community in the central part of the state. It was a warm, slumberous night. Strands of cirrus clouds, like wisps of smoke, drifted slowly across the moon’s bright surface. Crickets chirped in the surrounding fields, and the occasional night bird boomed its melancholy notes in the nearby woodlands.

On the outskirts of Plainfield, the moonlight lit the town cemetery with startling clarity. The loudest sound to be heard here was the chick of a shovel biting into the loose soil above the casket of a middle-age woman who’d been laid to rest earlier in the day. If any of the residents of Plainfield had happened upon this lonely spot, the scene they would have witnessed might have sent them fleeing for their lives—or screaming into insanity. Someone, or something, was digging up the freshly buried body.

Standing waist deep in the open grave was a short, gray-haired man of slender build. As he paused from his digging and listened for signs of intruders, a beam of moonlight illuminated his upturned face. It was a visage straight from hell. The man wore a leather mask made from the facial skin of a human being he’d previously exhumed and violated, stealing the head and genitals of the female corpse. This nightmare figure, this beast, was forty-five-year-old Ed Gein, a local handyman and loner whose twisted thoughts and horrid desires churned in his mind like a pot of writhing eels.

Edward Theodore Gein was a true original in the annals of American crime.1 Starting in the late 1940s, this grave-robbing abomination perpetrated some of the most ghoulish outrages ever committed by a man—and all because he wanted to be a woman, a longing prompted by his abiding love and reverence for his deceased, domineering mother.2 When finally revealed, Gein’s perversions would shock the world, ignite a firestorm of media coverage in his bucolic hometown, and inspire a slew of Hollywood horror films, led off by Alfred Hitchcock’s terrifying masterpiece Psycho. The irony of Ed Gein’s warped existence was that this fearsome necrophile, transsexual, and murderer was the quintessential momma’s boy.

Ed Gein was born in La Crosse, Wisconsin, in August 1906, the second son of George and Augusta Gein, an unhappily married German couple who endured one another’s presence solely because of their strong Lutheran beliefs. An alcoholic failure, George Gein was ridiculed by his wife as an example of male ineptitude. The strong-willed Augusta Gein also tyrannized her two sons, constantly preaching to them about the evils of the world. She bombarded them with Old Testament stories of sin and damnation, urging them to beware of scheming female temptresses. This bitter, angry harridan clearly had no love for any members of the human race.

Augusta Gein felt compelled to take over the responsibility for her family’s financial support from her ne’er-do-well husband.3 Shortly after Ed was born, she opened a grocery store in La Crosse. In 1914, she moved the family to a farm outside rural Plainfield, hoping to isolate her sons from the temptations of city life. Other than venturing off the farm to attend school, Ed Gein and his older brother, Henry, were virtual prisoners, subjected to an endless round of hard physical labor and verbal abuse.

The young Ed Gein was an average student, although he creeped out his teachers and schoolmates with his peculiar ways, which included the disconcerting habit of laughing at inappropriate moments.4 Effeminate and bashful, he had trouble making friends and was frequently attacked by bullies. Throughout Gein’s formative years, his entire life revolved around his sainted mother, who he always tried to please despite her constant hectoring. It would have taken a much stronger psyche than Ed Gein possessed to have emerged from that cauldron of wrath and angst without a warped personality.

The restricted, lonely lives of Ed and Henry Gein continued into adulthood. After their father died in 1940, the two men began doing odd jobs around town to help support the family. Perhaps because of his identification with his mother and his latent femininity, Ed started babysitting for neighbors. He seemed to get along better with kids than with adults, although the townsfolk in Plainfield regarded both Gein brothers as hardworking and honest.5 If only they’d known about those eels wriggling around inside Ed Gein’s head.

Unlike his younger brother, Henry Gein appeared to be emotionally stable. He managed to withstand his mother’s constant disapproval, and he didn’t share her hatred of the outside world. On occasion, Henry criticized his mother in front of Ed, which alarmed the younger Gein. That may have prompted the first violent expression of Ed Gein’s perverse nature.

One day in the spring of 1944, Henry and Ed set about burning off a marshy area on their farm. At the end of the afternoon, Ed was supposedly unable to locate Henry and reported him missing. However, when a search party arrived at the farm, Gein took the men directly to his brother’s dead body, which showed bruising about the head. Although the police were suspicious, they didn’t pursue the matter. The county coroner ruled that Henry had been asphyxiated by smoke from the fire. Henry’s death left Ed and his mother alone together in their bizarre self-exile.

Whatever joy Ed may have felt at having no competition for his mother’s attention was short-lived. Not long after Henry’s death, Augusta Gein suffered a disabling stroke. Ed nursed her tenderly during her illness, even sharing her bed at times. Then in December 1945, Augusta was felled by a second stroke and died, leaving her distraught thirty-nine-year-old son adrift without his guiding light. Over the next decade, Ed Gein became ever more unhinged mentally and morally, descending into madness while continuing to lead the life of an innocuous, retiring handyman.6 What the world saw and what went on in Gein’s mind and on the lonely farm out on the edge of Plainfield could not have been further apart.

The first symptom of Gein’s mental deterioration came immediately after his mother’s death, when he closed off most of the rooms in the family home, preserving his mother’s downstairs bedroom and parlor exactly as they were as shrines to her memory. Gein retreated to the kitchen and a small connecting room where he slept. Closeted away in those two rooms, Gein slipped into a macabre fantasy world. Ever since his school days, he’d enjoyed reading adventure stories. Now he began reading horror magazines and accounts of freakish Nazi medical experiments. He studied human anatomy, transfixed by the female body. Silently, the eels were slithering to and fro.

The residents of Plainfield didn’t pay much attention to what went on out at the Gein place until late in 1957.7 On November 16 of that year, Bernice Worden, the owner of a local hardware store, went missing. From her sales receipts, the police learned that the last thing Worden had sold before she disappeared was a half-gallon of antifreeze. Worden’s son, Deputy Sheriff Frank Worden, recalled that Ed Gein had been in the store a short time before and had commented that he needed some antifreeze.

The police paid a visit to the Gein farm. Gein wasn’t home, but the police proceeded to look for the missing woman. What they discovered traumatized some of the investigating officers.8 Hanging in a shed attached to the rear of the house was the naked body of Bernice Worden—what was left of her. Worden had been decapitated and disemboweled, slit from crotch to throat like a dressed-out deer carcass. As the police officers entered Ed Gein’s fetid, trash-filled farmhouse, their eyes fell on one horror after another.

The men found Bernice Worden’s heart in a plastic bag by the kitchen stove, and her entrails were wrapped in newspaper (Gein later said that he intended to burn them). The police recoiled at the sight of lampshades and chairs covered with human skin, several masks fashioned from human faces, and skulls sitting atop the bedposts in Gein’s room. They found bowls made from sawed-off skulls, a shoebox filled with female genitals, a belt made from nipples, and human lips dangling from a window shade drawstring. The gruesome array inside the farmhouse was almost more than the human mind could comprehend. And all of it was the handiwork of shy little Eddie Gein.

Bernice Worden’s head was discovered in a burlap bag, and the preserved face and scalp of another victim—local tavern owner Mary Hogan, who’d been missing since 1954—was found in a paper sack. The police also uncovered a vest-like wrap made from a female torso, a “woman suit” that Gein would admit to having worn around his house, along with other female body parts.9 At times, he even donned these “trophies” and danced about in his yard at night in a vile subhuman ritual.

Altogether, the police discovered the remains of at least ten bodies. Gein was arrested and eventually confessed to the murders of Bernice Worden and Mary Hogan, saying both victims reminded him of his mother. He maintained that the rest of the body parts had come from corpses he’d dug up in area cemeteries, which authorities were able to corroborate by opening some of the graves. Gein claimed that he’d never had sex with any of the bodies he exhumed or eaten human flesh. He told investigators that he had a different reason for gathering his sickening collection: after his mother died, he’d wanted to have a sex change operation, and he’d taken to adorning himself with the skin of women so he could feel what it would be like to be female.10

As word of Gein’s horrific crimes spread, reporters from all over the country—and even a few from abroad—descended on sleepy Plainfield. Every local who would stand still long enough was interviewed and quoted. Most people characterized Gein as odd, though seemingly harmless.11 A woman who said she’d gone out with Gein, Adeline Watkins, swore that he was “good and kind and sweet.”12 The Chicago Tribune ran so many gory features about the “Butcher Gein” and his “murder farm” that the editors felt compelled to apologize for their zeal, issuing a brief statement headlined “Enough of Gein” on November 22, 1957. “We take no pleasure in publishing stories of this kind,” the editors declared, “and will be glad when the case is no longer in the news.”13

During his interrogations, Gein never showed the slightest remorse for his actions, or any inkling of the monstrous nature of his crimes. He talked about his savage deeds with detachment, mentioning that he’d interrupted his dismembering of Bernice Worden to work on his car and play with the cash register he’d stolen from the hardware store. A photograph taken at the time shows Gein smiling like a minor celebrity, apparently oblivious to the fear and revulsion he stirred in onlookers. When grilled on the specifics of his murders and grave-robbing episodes, Gein said that he couldn’t recall the details, claiming that he’d gone into a “daze” each time.14

It was obvious that Gein was hopelessly deranged. Doctors found him mentally unfit to stand trial, and a circuit court judge committed him to a state hospital for the criminally insane. A few months after his commitment, the county put his farm up for sale, but before anyone could buy it, the farmhouse burned to the ground. The Plainfield fire department arrived too late to extinguish the blaze. Arson was the likely cause of the fire, although no one was ever held accountable. When told that his family home was gone, Gein replied, “Just as well.”15

A decade after Gein’s arrest, his doctors determined that he was competent to stand trial. In November 1968, Gein was found guilty of first-degree murder in the death of Bernice Worden. He was also judged to be legally insane at the time of the crime and was returned to a state psychiatric institute. He remained institutionalized until he died of cancer in 1984 at the age of seventy-seven. Gein’s doctors remarked that he was an ideal patient, never violent and always cooperative.16 The only sign of his psychosis was the frightening manner in which he stared at females—not a look to invite conversation.

It was inevitable that Gein’s grisly crimes would attract the attention of the entertainment industry. In 1959, Robert Bloch, a horror and science fiction writer, published his Gein-inspired novel Psycho. The following year, Alfred Hitchcock turned Bloch’s book into the chilling movie of the same name, featuring murderous momma’s boy Norman Bates cavorting with his mummy’s shriveled corpse. In 1974, the slasher franchise The Texas Chainsaw Massacre debuted, with the killer-cannibal Leatherface sporting a mask of human skin, a direct take-off on Gein.17 And in 1991, the mind-warping movie The Silence of the Lambs introduced us to serial killer Buffalo Bill, a demented transsexual who slays and flays his female victims in order to make a garment of their skin, just like Ed Gein’s woman suit.18 Had Gein not committed his crimes, who knows, Hollywood scriptwriters might never have conceived of such ghastly characters.

That the real-life monster Ed Gein could reach such depths of depravity attests to the unknown boundaries of the evil that humans are capable of. The judge who presided over Gein’s murder trial, Robert H. Gollmar, said, “I know of no person like him in the whole history of the world.”19 After his atrocities came to light, a number of sick jokes, songs, comic books, and even fan clubs grew up around Ed Gein—examples of psychological coping, false bravado, or shock-value exploitation. But the man was no pretend slasher that we can laugh about when the house lights come up. He was and is a dark feral specter, a night-roaming apparition that flutters at the edge of consciousness and sends shivers through your soul.