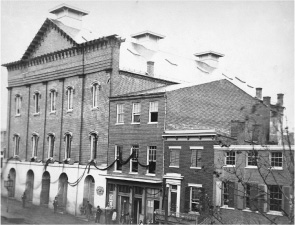

Ford’s Theatre (left), scene of John Parker’s disgrace

April 14, 1865, dawned balmy and bright in Washington, DC. It was Good Friday, and the sunny weather seemed to reflect the spirits of Washingtonians. Just days before, Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy, had fallen, followed quickly by the surrender of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House. The Civil War was all but over.

The capital erupted in celebration at the news. After four years of conflict and doubt, it was finally time to whoop it up. All over town, the air shook with fireworks, cannon salutes, and wildly clanging church bells—startling horses, dogs, and the occasional meandering cow. Bands raced through “Yankee Doodle” and “Rally ’Round the Flag, Boys” again and again.

Cheering crowds surged through the dusty, unpaved streets. In makeshift hospitals around the city, smiles creased the haggard faces of wounded soldiers. Former slaves cavorted with joy, and drunken laughter spilled from the city’s plentiful saloons and bordellos. “The entire population of Washington seemed to be abroad,” wrote historian Margaret Leech, “shaking hands and embracing, throwing up their hats, shrieking and singing, like a carnival of lunatics.”1

Even the president felt the urge to let off steam. Abraham Lincoln needed the break. The war had made an old man of him. He was gaunt and pale, and he complained that his hands and feet were always cold. He’d been haunted by a dream of himself lying in state in the East Room, cut down by an assassin. A night out would do him good, mentally and physically. Mrs. Lincoln suggested a play. Our American Cousin, a popular comedy about an awkward young Yankee and his aristocratic English kin, was ending its run at Ford’s Theatre. That would be just the tonic the president needed.

Following Lee’s surrender, General Grant returned to Washington. Lincoln knew it would be good for people to see their president and his victorious general enjoying an evening out, and he urged Grant and his wife to accompany him to the play. Grant halfheartedly accepted then later changed his mind, claiming he needed to leave Washington and get back home to New Jersey to see his children. The truth was that Grant had grown tired of all the public adulation. Besides, his wife couldn’t stand Mrs. Lincoln, an unpredictable, short-tempered woman.2 Mrs. Grant had witnessed the first lady’s tantrums—and been a target of them on occasion. Spending over two hours cooped up with her in a tiny theater box would be torture.

When Grant turned him down, Lincoln was inclined to cancel the evening altogether, but newspapers had already announced he’d be attending the play, and Ford’s Theatre had gone to the trouble of decorating the president’s box with flags and a portrait of George Washington. To avoid disappointing anyone, Lincoln agreed to go ahead with the outing.

After Grant backed out, Lincoln invited Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. However, Stanton’s wife also kept her distance from Mrs. Lincoln, and they begged off. At the last minute, Mrs. Lincoln invited a young couple to fill out the party, Maj. Henry Rathbone, a strapping soldier with impressive muttonchop whiskers, and his fiancée, Clara Harris, daughter of Senator Ira Harris of New York.

The Washington Metropolitan Police Force was to furnish an armed officer to accompany the group. While it’s hard to believe that a single policeman would be the president’s only protection, that wasn’t unusual. Lincoln was cavalier about his personal safety—despite a near-miss attempt on his life in August 1864.3 He’d often take in a play or go to church without guards, and he hated being encumbered by the military escort assigned to him. Sometimes he even walked alone at night between the White House and the War Department, a distance of around a quarter of a mile. But Lincoln’s staff took the frequent threats against the president seriously. A bodyguard made sense, especially given the chaos in the capital at the end of the war. The man the police department assigned to the job was John Frederick Parker. If a committee had spent days pondering the matter, it couldn’t have come up with a worse choice. Parker’s staggering incompetence would lead directly to a national tragedy.

Born in Frederick County, Virginia, in 1830, John Parker moved to Washington as a young man. In 1855, he married Mary America Maus. The couple would have three children together. Originally a carpenter, Parker had become one of the capital’s first one hundred fifty officers when the Metropolitan Police Force was organized in 1861.

Parker’s record as a cop fell somewhere between pathetic and comical. He was hauled before the police board over a dozen times, facing a smorgasbord of charges that should have gotten him fired, but he received nothing more than an occasional reprimand.4 His infractions included conduct unbecoming an officer, using intemperate language, and being drunk on duty. Charged with sleeping on a streetcar when he was supposed to be walking his beat, Parker declared that he’d heard ducks quacking on the streetcar and had climbed aboard to investigate.5 The charge was dismissed. When he was brought before the board for frequenting a whorehouse, Parker argued that he’d only been there to protect the place—like a bank robber claiming he’d taken the money to safeguard it.6 That he kept getting away with such behavior says as much about the police department of the period as it does about Parker.

In November 1864, the Metropolitan Police Force created a permanent detail to protect the president, made up of four officers. There must not have been any performance standards for the group, since John Parker was named to the detail. Parker was an unlikely candidate to protect anyone. He was the only officer with a spotty record, so it was a tragic coincidence that he drew the assignment to guard the president on the night of April 14.

As usual, Parker got off to a lousy start that fateful Friday. He was supposed to relieve Lincoln’s previous bodyguard at four o’clock but was three hours late. When he finally showed up at the White House, Parker was ordered to report to Ford’s Theatre and wait there for the president and his guests.

Lincoln’s party arrived at the theater at around nine o’clock. The sparkling morning had given way to a foggy, chilly evening. The play had already started when the president and his companions entered their box directly above the right side of the stage. The flags put up in honor of the president’s visit draped the front and sides of the box, a lively contrast to the somber crimson wallpaper that darkened the interior. The actors paused while the orchestra struck up “Hail to the Chief.” Lincoln bowed to the applauding audience and took his seat in a comfortable upholstered rocking chair. Witnesses reported that relief and happiness seemed to soothe Lincoln’s craggy, careworn face.7

Officer Parker was stationed in the narrow passageway outside the president’s box, seated in a chair beside the door. Parker’s irresponsibility soon revealed itself. From where he sat, Parker couldn’t see the stage, so after Lincoln and his guests settled in, he abandoned his post and moved to the front of the first gallery to enjoy the play. Later, Parker committed an even greater folly: at intermission, he joined the footman and coachman of Lincoln’s carriage for drinks in the Star Saloon next door to Ford’s Theatre.8

John Wilkes Booth entered the theater sometime before ten o’clock. Ironically, he’d also been in the Star Saloon, working up some liquid courage. When Booth crept up to the door to Lincoln’s box, Parker’s chair was still empty, giving the assassin unfettered access to the president. Booth timed his attack to coincide with a scene in the play that always sparked loud laughter. Some of the audience may not have heard the fatal pistol shot, although inside the president’s box it must have been deafening.

No one knows if John Parker ever returned to Ford’s Theatre that night. When Booth struck, the vanishing policeman may have been sitting in his new seat with a nice view of the stage. Perhaps he stayed put in the Star Saloon. Just as likely, he could have been ensconced in the nearest cathouse—or leaning against a lamppost staring at the moon.

Even if Parker had remained at his post, it’s not certain he would have stopped Booth. According to an interpreter at today’s Ford’s Theatre National Historic Site, “Booth was a well-known actor, a member of a famous theatrical family. They were like Hollywood stars today. Booth might have been allowed in to pay his respects. Lincoln knew of him. He’d seen him act in The Marble Heart, here in Ford’s Theatre, in 1863.”9 However, had Parker been present to admit Booth to Lincoln’s box, Booth would have lost the element of surprise and his attack might have been thwarted.

A fellow presidential bodyguard, William H. Crook, wouldn’t accept any excuses for Parker. He held him directly responsible for Lincoln’s death. “Had he done his duty, I believe President Lincoln would not have been murdered by Booth,” wrote Crook. “Parker knew that he had failed in duty. He looked like a convicted criminal the next day. He was never the same man afterward.”10 Nevertheless, Parker escaped punishment for his actions. Although he was charged with failing to protect the president, the complaint was dismissed. No local newspaper bothered to follow up on the issue of Parker’s culpability, and he wasn’t mentioned in the official report on Lincoln’s death. Why he was let off so easily is baffling, although in the upheaval following the assassination, perhaps he seemed like too small a fish to bother with.

Incredibly, Parker remained on the White House security detail even after his pitiful performance. At least once, he was assigned to protect the grieving Mrs. Lincoln before she moved out of the presidential mansion and returned to Illinois. (Prior to the assassination, Mrs. Lincoln had written a letter on behalf of Parker exempting him from the draft, and some think she may even have been related to him on her mother’s side.)11 Mrs. Lincoln’s dressmaker and confidante, former slave Elizabeth Keckley, recorded this outburst by the president’s widow directed at Parker:

“So you are on guard tonight—on guard in the White House after helping to murder the President.”

The shaken Parker made a feeble attempt to defend himself:

“I could never stoop to murder—much less to the murder of so good and great a man as the President. . . . I did wrong, I admit, and have bitterly repented. . . . I did not believe any one would try to kill so good a man in such a public place, and the belief made me careless.”

Mrs. Lincoln snapped that she would always consider him guilty and ordered him from the room.12

Parker remained on the Metropolitan Police Force for three more years, but his shiftlessness finally did him in. He was fired on August 13, 1868, for once again sleeping on duty. Parker drifted back into work as a carpenter. He died in Washington in 1890, of pneumonia. Parker, his wife, and their three children are buried together in the capital’s Glenwood Cemetery—on present-day Lincoln Road. Their graves are unmarked.

No photographs have ever been found of John Parker. Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg wrote him off as a “muddle-headed wanderer . . . a weird and elusive Mr. Nobody-at-All—a player of a negation.”13 Parker remains a faceless character, a clown who fostered a tragedy. But what might have happened if Parker had done his duty and not abandoned his president?

Obviously, if Booth had been turned away, President Lincoln would have lived and would probably have served out his term in office. If that had happened, some of the acrimony of Reconstruction might have been avoided, and racial equality would surely have been advanced more forcefully, possibly improving race relations today. Whatever the outcome, we know that Lincoln would have applied the balm of forgiveness to the nation’s wounds. That opportunity for Lincoln to at least attempt to forge a fairer, more united United States is really what the feckless John Frederick Parker stole from the country.