"So, what was the significance of all this?”

Three weeks later, as I was telling the story of our Ayahuasca experience, my dinner companions were skeptical. They included three biologists and a lawyer, and all were high-powered professionals from Chicago. My friend Paul Beaver, who has a Ph.D. in biology, called this group “the Scientists” and considered them big guns. He thought it important for me to get to know them. They were all members of the board of directors of the Chicago-based Rainforest Conservation Fund, which has supported the now more than one-million-acre Tamshiyacu-Tahuayo community reserve just outside Paul’s camp since its establishment in 1991. It was the first reserve in Peru to be run for the benefit of the people living on its periphery as well as its plants and animals—an extremely unusual approach, I realized, but one that, possibly, held out realistic hope for preserving the pink dolphins’ world.

Except for its current president, none of the board members had ever laid eyes on the reserve or met any of the people their funds were meant to support—until now. The group had decided to spend two weeks that June exploring the reserve they had helped to found. Intrigued by the group’s premise, and eager to learn more about the rain forest from the scientists, I gratefully accepted the invitation to accompany them.

While Dianne was on an errand in England, I now found myself back in Peru, sitting with my new friends at one end of one of the long wooden tables at Paul’s lodge, drinking beer and Cokes in the flickering lamplight and telling each other our stories.

Jon Green, a tropical biologist with a specialty in invertebrate physiology and a professor at Chicago’s Roosevelt University, thought taking Ayahuasca was dangerously foolhardy. Jon was not a man of excessive caution: With his wife, Joy Schochet, a developmental biologist, he had spent most of two decades in Thailand and Malaysia, elbowing aside crocodiles and venomous snakes to sieve worms and crabs out of the mud. His question about the significance of my experience was tongue-in-cheek: To his mind, the only significance of the visions was the drug’s physiological disruption of normal brain chemistry. But Jon, like me, was a Star Trek fan, and he wondered what the shaman had made of my vision of the Starship Enterprise.

Ricardo had interpreted the jaguar vision first, I explained. The jaguar, he had told me, had been sent by the dolphin spirits as my defense on the journey. “Everywhere, in your house, in the canoe, walking on the ground, you will have the jaguar as your defense, watching over you like a shaman,” he had told me through Moises. “The jaguar is very powerful. Every day in the Amazon, a thousand thousand people going to die—but you have your defense. Maybe the Mother of the Vine knows about the tigers”—and here he was referring to my work in India—“and that is why she gives the jaguar.”

My own eyes staring back at me beneath my eyelids Ricardo had ignored. (I later learned from a friend back in the States, Cindy Thomashow, who had studied shamanic trances, that an image like this is a common element in vision quests, meant to focus introspection before journeying further.) But the Starship Enterprise was another matter. A long train of Spanish and Quechua had followed my account of the vision, as Moises tried to explain to Ricardo what a spaceship is. Once he understood, though, its significance was clear. Normally, the spirits send a canoe in which to travel to their realm, he explained; but because I was a foreigner from a country so technological, they had instead sent a spaceship. Or perhaps, I later thought, they had sent a spaceship because I still had so far to go.

Dave Meyer, one of the top medical malpractice lawyers in Chicago and a skilled naturalist, listened to my story and laughed uncomfortably. “But you don’t believe any of this, do you?”

Did I?

“I know Don Ricardo was not lying to me,” I said carefully. “I think that what he is saying, and what the people believe about the dolphins, and the way they see the world, is true—but maybe not in the literal sense that we understand.”

“But this nonsense about the Encante, and dolphins turning into people,” Jon broke in. “These dolphins are a biological species—they don’t have magical powers!”

“Don Jorge told me he has seen the dolphins come out of the water,” said Greg Neise. The Fund’s charismatic young president, Greg was the only member of the board who had been here before. Greg had often stayed and traveled with Jorge Soplin, an elderly local expert on uses of the native plants. “He says they come out and stand on their tails and have the most enticing female figures you’ve ever seen. At the Quebrada Blanco, one did it to him, but he turned around and split—he knew it was really a dolphin.”

“Oh, come on,” said Dave.

“Well,” said Greg, “strange things happen here.”

Greg was the only one among us without a college degree; he has learned what he knows by experience. A big, bearded man in his mid-thirties, he tied his long blond hair in a ponytail, and his third finger bore a tattooed cross, a souvenir of a brief association with a Chicago-land gang. Greg taught himself photography and computer design. Income from the latter enabled him to travel widely in the tropics, particularly in Costa Rica and Peru.

“This happened to me,” Greg continued. “We were walking along the Quebrada Blanco, me and Don Jorge and some others. And we understood what the other was thinking. Without speaking, he directed me through the most difficult landscapes. When one of us saw a group of animals, the other knew it. We had some kind of awareness that we in the city do not have. There was some form of telepathy. And it goes against everything I think and believe. And it happened among people who—why, I didn’t speak a lick of Spanish then and half the words were in Quechua anyway. Yet I knew what they were thinking as if we were talking. And there were no hand signals.”

Gary Galbreath, a paleontologist who teaches biology at Northwestern University, abhors superstition, and subscribes to the Skeptical Inquirer, a magazine that debunks pseudoscience like ESP. But he is also a diplomat, RCF’s president before Greg. He looked at Greg’s story, as he does most things, from an evolutionary perspective. Perhaps Greg had been reading body language, he offered; as cooperative hunters, our ancestors silently communicated with one another for eons. “I bet we can still respond on a level we don’t normally use,” Gary said.

Greg continued: “I didn’t even realize this was happening until we got back to Iquitos, and it was suddenly gone. Jim, too, has had this happen with people he didn’t know.” Jim Penn, the field director for the reserve’s agroforestry project, has worked here in the reserve for more than two decades, in the early days living off money he made painting houses in Chicago in the summer. His wife, Doris Catashunga, is Peruvian, and the people who live in the villages that ring the reserve are among his closest friends. Jim, with intense brown eyes the color of the earth and skin that seems perpetually sunburned from his hard work in the field, had joined our small group at the end of the long table. So far, he had listened quietly, but now he spoke: “The thing you’ve got to remember, is these people are as smart as you and I. There are reasons for their beliefs. And if you dismiss what they say, they’ll pick up on it right away.”

In the morning, we set off for the reserve. In two motorized aluminum canoes, we cruised up the Tahuayo to the seasonal white-water stream called the Quebrada Blanco. Our group numbered fourteen: Besides the RCF board members, Dave had brought his teenage son and nephew; Jon had brought two of his students; and a handful of other RCF members had come along, including wildlife photographer Jim Rowan.

As the waters narrowed, the forest seemed to quicken: Partially submerged trees trailed curtains of vines. The air, hot as breath, shuddered with the calls of parakeets, the glittering wings of dragonflies. Strangler figs flowed over their hosts like melting candles; ferns uncoiled, curling and twisting like dancers. Trees hung heavy with the nests of ants, wasps, termites, birds.

“There’s never been a botanist in here,” Greg yelled to me over the noise of the motor. “Who knows how many new species we’re looking at!”

Actually, the leading expert on Latin American botany, Al Gentry, had come here, shortly before he was killed in a 1993 plane crash in Ecuador. He’d told Greg the place was very odd. He’d seen plants here that were not known in Peru. Ornithologist Ted Parker had the same reaction: “These birds shouldn’t be here,” he’d told Greg. Some of the species he saw were known only from Brazil. More than seven hundred species of birds have been recorded in the reserve—so far.

Greg and I had talked about this over the phone in the States, before we had met. “It’s a really strange area,” he’d told me. “Rivers flow in opposite directions, even though the land is flat as a pancake. I’ve seen the water in the river go up and down thirty-six feet in twenty-four hours. Tree ferns are growing in the understory, which you don’t find in lowland rain forest. I’ve never seen anything like it. It’s like something from the Cenozoic.”

Unlike most of the Amazon, the Tamshiyacu-Tahuayo area has been a rain forest since before the river itself was born. Based on fossil evidence, paleogeographers believe that during the last 50,000 years, the Amazon basin became cooler and drier at least four times, and most of its rain forests changed to savannas. Fewer than a dozen small patches in the entire Amazon basin—comprising perhaps 15 percent of its size today—remained wet and warm enough to preserve the ancient lineages that thrived in the lush, steamy world of the Eocene, the dawn epoch of the Cenozoic. This was one of them.

“Where is the reserve? Are we in the reserve?” I kept yelling over the motor. Greg laughed. “Someone else who came here said, ‘ I went to your reserve and I didn’t see any conservation work going on—it was just pure forest.’ And I said, ‘ Exactly!’”

There are larger reserves in Peru—Pacaya-Samiria, on the western side of Loreto province, covers 5 million acres, five times the size of Tamshiyacu- Tahuayo—but none is more pristine. Because of its beauty and diversity (including a population of more than 700 pink dolphins, studied by the chair of the Cetacean Specialist Group of the World Conservation Union, Stephen Leatherwood, until his death from cancer in 1997) Pacaya-Samiria has been designated as a protected area since the 1940s. But in Peru, as in much of the Third World, merely establishing a reserve does not guarantee its protection; regulations do not ensure that the government enacting them will either enforce or even obey its own laws.

Much of the land is protected on paper only: During the 1970s, oil companies drilled no fewer than seven wells inside its borders, and one of them is still pumping. In 1991, only an intense campaign by American environmentalists, including the Nature Conservancy, kept the Peruvian government from granting Texas Crude a license to further explore and extract oil from the reserve. The Peruvian Fisheries Ministry has, in fact, granted commercial fishing companies licenses to seine the rivers inside the reserve with their giant gill nets, drowning pink river dolphins, tucuxis, manatees, and giant river otters. Despite the law and twenty park guards to enforce it, some 10,000 people, many of them with cattle, are living inside that reserve, besides the 60,000 in villages surrounding it. And the waters are silting with runoff from the 180,000 acres of rain forest that were illegally cut to the west in the Huallaga River basin to grow coca for cocaine.

But the Tamshiyacu-Tahuayo reserve has no such scars. There is no commercial logging; no oil drilling; no cattle grazing inside its borders. No sign announces the boundaries of the reserve, either. No forest guard stood watch as we entered—only a pygmy marmoset, clinging with orange hands to a spine-covered chambira palm. Its black-ringed, tawny tail hung down like a lizard’s.

Moises and Mario pulled the canoe near shore and we waded through the mud. A narrow path, cut by Mario, led into a twilight world: though the sun had been bright on the river, here in the forest the light was a soft, dim green. Crickets sang as though it were evening, or right before dawn.

We walked slowly, not in apprehension but amazement. Everywhere we encountered creatures none of the biologists had seen before: climbing ferns spiked with four-inch thorns; a low-growing herb with ginkgolike leaves, fringed with brown spores—which Moises told us, incredibly, was a palm. Jon and Joy stood transfixed by a delicate white fungus growing on a fallen machi-mango fruit. “George Lucas wouldn’t have had to use his imagination,” said Jon. “He could have just come here. Imagine this thing the size of Jabba the Hutt!”

With Moises’ and Mario’s help, Mark, Greg, Jim, Dave, and the boys dove after frogs, spiders, millipedes, and beetles. At the day’s end, they had collected eleven Ziploc bags of animals to take back to camp to be identified and photographed before they would be freed the following morning. Among them was a brilliant, two-inch green and black frog unlisted in any field guide. But Moises knew it, though not by any Latin name. It was one of the frogs the people on the Napo River use to produce poison for arrows and blowgun darts. In poison glands scattered all over the body, frogs of this family, Dendrobatidae, produce some of the most potent toxins in the world—so poisonous that one species, the bright yellow Phyllobates terribilis, will burn your skin if you touch it. One frog can provide enough secretion to poison fifty darts, which remain potent for a year. The poisonous secretions of another frog, which the Mayorunas call dav-kiet!, is used to produce sapo, a paste which is applied to the skin through a burn wound. Though at first sapo causes great pain—the blood rushes as if the heart will burst—its later effects are worth the ordeal. The drug heightens the senses and strengthens the body, allows you to see in the dark, sense the powers of plants, and foresee the plans of animals. The frog who gives these powers is held captive for three days before its poison is removed through gentle scraping, and when it is set free, village children run after it, wishing it a good journey home.

With the others bent over their frogs and fungi, I looked for Gary. On the long boat ride from Iquitos to the lodge, Gary had begun to tell me about some of the prehistoric animals who had inhabited South America millions of years ago. At the time pink dolphins may have entered the Amazon from the Pacific, 15 million years ago, the dominant predators on the continent were wolf-toothed marsupials called boyhyaenids, who carried their young in pouches like kangaroos, and six-foot-tall terror birds, who were essentially feathered dinosaurs, 50 million years after dinosaurs had gone extinct. Only in the previous months had paleontologists found the forelimbs of the giant birds, Gary had told me, and the discovery was a shock. Though the creatures were clearly birds, with feathers and beaks, they did not have wings: they grabbed their prey with grasping, three-fingered arms. Listening to Gary was like standing beneath some magnificent, fruiting tree, where you are showered with stories and facts and theories so exotic and delicious you swallow each greedily and wait hungrily for more. It’s no wonder Gary’s students love him and year after year vote him one of the best teachers at Northwestern.

But now the professor was uncharacteristically silent. He stood at the edge of a swamp. Gary’s green eyes were illuminated by some inner light, focused on something in the distant past. I touched his arm. “Where are you?” I asked.

“Carboniferous,” he said softly.

His words came as an echo from 300 million years back in time—back to when South America, frigid and sometimes glaciated, huddled with Africa, Australia, India, and Antarctica in one giant continent near the South Pole. But the landmass that would become Europe and North America, hovering over the equator, contained vast, dreaming swamps: the world’s first rain forests. Back before the plants had learned to flower, back before the animals learned to lay hard-shelled eggs, back before hearts beat with four chambers, day-long twilight glowed green through the scalelike leaves of thirty-foot-tall club mosses. Two hundred fifty million years before the first grasses evolved, tube-shaped plants called horsetails grew skeletons of silica, and ferns danced and curled into fifty-foot trees. Six-foot, flat-headed amphibians lounged in blood-warm shallows. The ancestors of the millipedes now in our Ziploc bags grew six feet long back then, and dragonflies soared on the wing spans of macaws. The Carboniferous was the cradle of Eden. During its 75-million-year reign arose the three lineages that would lead to the vertebrates that dominate the land today: the salamanders and frogs, the reptiles and birds, and the four-legged, lizard-like animals called synapsids that, many millions of years later, would lead to dolphins and to scientists.

Dawn itself, as Gary saw it, was preserved in the green glow of this rain forest swamp. This place preserved not only the strange, ancient pink dolphins in its rivers, but the future glimmer of dolphins encoded in the genetic material of the first fleshy-finned fish ancestors who emerged from shallow swamps like these. The ferns and millipedes had outlasted the driftings and collisions of continents; the dragonflies had survived desiccation, asteroids, cataclysmic extinctions. But could this place now survive the apocalypse of human greed? In this era of bulldozers and oil wells, gill nets and cattle ranches, what could preserve its future?

This was the task that the Rainforest Conservation Fund took on when Jim Penn first approached the group with the idea of protecting a reserve. Previously, the group had contributed money to projects in Costa Rica and New Guinea. “We were looking for a project that wouldn’t happen if we didn’t do it,” said Gary, who had been president when Jim came to them with his idea. RCF could not afford to finance guards, or to open and staff an office in Iquitos. But this, Jim pointed out, was fortunate: “What you think conservation is in the United States doesn’t work here,” he told them. In fact, almost everything we think of as effective conservation in the States has backfired horrendously in Peru. Jim knew from his years of work here that laws don’t protect the land. Officials are commonly bribed. Guards do not protect the land. In fact, park guards are often the most notorious poachers. Ecotourism seldom protects land. Unlike at Paul’s lodge, where the staff is employed full-time and have health and retirement plans, at most lodges, the support staff are paid only during the busy season. To supplement their sporadic income, they work part-time for logging operations and poach game to eat and to sell at the market in Iquitos.

To the local people at Tamshiyacu-Tahuayo, Jim explained, “conservation means gringos, fancy cars, ecotourism. Conservation is people sitting behind big mahogany desks in offices in Iquitos and Washington. Conservation is a business”—one that employs scientists and bureaucrats in the business of telling local people what they can and cannot do in their own backyards.

Instead of implementing a conventional conservation scheme, Jim asked the Rainforest Conservation Fund to secure this land’s protection by supporting the people’s old ways of guarding it—ways that don’t sound or look like conservation at all.

Today parts of the reserve are still vulnerable; but on two sides, thanks to the people who use the reserve, its boundaries are secure. The southern half of the reserve is guarded by warring Indians, the Mayorunas and their enemies, the Remos; it is simply too dangerous for loggers or cattlemen or oil explorers to enter there. And along the western border, where 175 families lived in the six villages Dianne and I had passed daily, the reserve is protected by a growing fortress of orchards.

“This is sangre de dragon,” Jim says, as Don Jorge points to a sapling with heart-shaped leaves. “It means ‘ blood of the dragon.’ It yields a red resin that heals skin burns, wounds, dysentery, and internal ulcers. It stimulates regrowth of tissue.”

Jorge speaks, and Jim translates for us. Jorge is slender, wiry, and spry, with the face of an imp and a smile that gleams with dental gold. His hair is soft and curls like a cherub’s just above his shoulders, with a strange white patch in the back as if he slept with his head in a shallow pool of Clorox. He does not seem seventy-one years old.

This two-foot sapling? Its name is ojé, Jim translates for us, a species of ficus, whose latex can be fermented into a medicine to kill six kinds of intestinal parasites. This spiny, climbing vine is called cat’s-claw. Dutch scientists are investigating its abilities to build up the immune system of HIV patients, Jim adds. The people use the bark of the yerba santo, or saint’s weed, to make a medicine to deliver miscarried fetuses.

“Everything in here is useful,” Jim says. “This is exceptionally diverse, with over sixty different species.”

As we follow Jim and Jorge along a slender trail, Jorge briefs us on the plants we meet as if introducing us to old friends—as Moises did in the rain forest with Dianne and me. But we are not in the rain forest. We are at the edge of the reserve. Though all these are rain forest plants, and the place looks exactly like a young forest, this is his chacra, planted on fallow land—an orchard at once jungle and garden.

This cedro is an important lumber tree, for making furniture. And this bush is ajo sacha, which will yield a garlic-scented tea to reduce fever and cure colds. From this cashapona, a spine-fringed, stilt-rooted palm, you can make the gating around your house. But it has another use, too, Don Jorge tells us: it’s a penis enlarger. How does it work? Well, first, of course, it is necessary to scrape off the spines. Then the bark is plastered against the penis for fifteen minutes. This must be done on three consecutive nights, during a new moon. Why? Because new moons cause things to grow long and thin, while full moons cause growth that is short and wide.

Such is the case with trees as well. Jorge is careful to prune his cainito tree, which produces a delicious fruit, during the full moon, so it, too, will grow full.

Many of the trees in his chacra bear fruits whose very names evoke luscious motions of lips and tongue: mango, guaba, aguaje, araza. The ungurahui’s purple fruit contains a seed that makes a chocolate-flavored drink; a garland of snail shells hangs from one of its branches. What are they for? I ask. “These snails have a ton of eggs,” Don Jorge answers through Jim. The snail shells, he explains, inspire the tree to fruit.

I can feel the scientists silently chuckle now. But there is a loveliness in Don Jorge’s gesture, a grace to it, like lighting a votive candle at church. The snail shells, in fact, may supply some calcium to the soil, an important nutrient; but we would be wrong, I think, to imagine that Jorge believes hanging snail shells works like spreading lime on a lawn. Rather, this is an offering, a sacred conversation with the plant, a living creature whom he likes and respects. For the relationship between Don Jorge and the plants here is quite different from the relationships between people and plants at home.

It is important, Don Jorge later told me, never to enter the chacra when you are not in the right frame of mind. No one should enter their chacra drunk, for instance. He handed a pepper to Dave’s nephew, who casually tucked it into his pocket. Don Jorge was upset. No, said Jorge, you mustn’t carry it in that way. It will bring bad luck. You must carry it in your hands, with respect.

Paul’s business partner, Suzy Faggard, who accompanied our group to the lodge, had made a wise observation about the people here when we’d spoken earlier. No wonder people here feel close to nature, she’d said, because in the rain forest, they are literally enclosed by it. In its twilight green glow, beneath a canopy of leaves that obscures the sky, one does not imagine the blue eye of God staring down at them from heaven; instead they live encircled by a leafy world, as if by a mother’s arms. Although, after two hundred years of evangelism, almost everyone here is nominally Catholic, their traditions are older, and closer to the earth. Miracles do not come from the sky, but they come commonly from the water: magic springs forth in the form of the dolphin, the anaconda, the whirlpool. And power dwells in the plants. For communion in church, the people have learned to drink the blood of Christ; but in a more ancient communion, they drink the blood of plants, to transport them back to the real world, the world that isn’t a dream, the world in which we can still hear the voices of animals and spirits speaking to us, and where spirits send canoes and spaceships to carry us on our travels.

In other cultures, spiritual ecstasy is induced by fasting, or song, dance, or ordeal. Here, ecstasy’s source is green. The vine snaking up this tree, Jorge tells us, is ayahuasca. He keeps it, he says, in order to see visions and dream dreams. To help it grow, he places in its boughs offerings of his wife’s hair.

We follow Jorge and Jim, the professors and biologists and other professionals taking notes. Our teacher is a man who offers snail shells to trees, who was nearly seduced by a dolphin, who can speak without words. And yet, Jim describes Jorge with words one might reserve for a scientist: He has learned by experiment. “Thanks to his ability to experiment,” Jim says, “he has been able to help me immensely.” For more than a decade, and throughout Jim’s doctoral work in agroforestry in Peru, Jorge has been one of his most important mentors. “He is not interested in money, but he’s a real expert, and he loves to experiment with plants.”

Over many years, Jorge has learned not only the uses of these different species, but also which ones thrive in different types of soils and under different methods of cultivation. He knows that an aguaje palm planted in the lower part of his chacra will grow five times as large as one planted in the upper part. Jim tested the acidity of the soil and discovered a difference in pH of only .5—a difference that can be profound. Because of his experiments, Jorge understands that guava fixes nitrogen in the soil in which it grows; he knows that spiny palms prefer the richest soils; he knows that ajo sacha is a bush in its female form and a vine in the male, and that the female form is more curative. But by offering his trees snail shells and human hair, he shows he understands something even more important: that the fates of the plants and the animals, the people and the dolphins, the land and the water, are all linked.

The plants in this chacra, Jim believes, are the trees that will save the forest. It’s a truth well illustrated by a tree he next shows us: the palm called aguaje.

Greg had told me about the aguaje before we left the States. I had tasted its fruit with Dianne on the previous trip. It is covered with many dozens of dark red scales, and looks rather like a hand grenade. The thin flesh covering the large seed is the color of Gouda cheese. Its taste is bland, but most people do not eat it; rather, they sell it in Iquitos, where it is used to flavor ice creams and drinks. “More aguaje comes through Iquitos today than did Hevea latex at the height of the rubber boom,” Greg had told me on the plane ride from Miami to Lima. The highest-quality fruits, he said, garner $10 to $20 per twenty-kilo sack—a price up to $2.20 per pound. So prized is the fruit that people come from all over the province to compete for the same stands of female trees in the forest.

The harvest is difficult and dangerous. The glass-smooth trunk of the palm is nearly impossible to climb and can soar for 130 feet before giving way to a starburst of spine-covered fronds and its clusters of scaly fruit. Collectors don’t wait for the fruit to drop; monkeys and birds would get to it first. Instead, the first collectors to arrive cut the trees down to prevent others from doing so—often before the fruits are even ripe. Unripe fruit sells in the Iquitos market for $1.50 to $3 for a forty-kilo sack—as little as 4 percent of the price of ripe aguaje. When, as a student in the 1980s (he now teaches at Grand Valley State University in Michigan), Jim began documenting this phenomenon with Richard Bodmer (now with the Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology in Canterbury, England) and McGill University’s Oliver Coomes, they called it “the race for aguaje”—a race no one wins.

“It was a lose-lose situation,” Jim explained. “Every year people worked harder and harder to further extinguish a valuable resource.”

For forest animals, the destruction of aguaje was a disaster. Not only do these fruits feed monkeys and birds, but they are also surprisingly crucial to hoofed animals. For his doctoral thesis, Richard Bodmer discovered that fruit, and not grasses or leaves, provides a full 87 percent of the diet of the gray brocket deer and well over half the diet of collared and white-lipped peccaries. Aguaje alone, he found, comprises nearly a third of the diet of the lowland tapir. Finding a way to protect the fruiting palms, he wrote, was a project needing “urgent attention.”

Ironically, only a generation or so ago, local people grew aguaje in their chacras. But most people had abandoned the old way of farming. “The government-sponsored programs tell people the way they live is backward and savage,” Greg had explained. “The way to be part of modern Peru is to have cattle and corn.”

Even the conservation organizations backed the cattle-and-corn schemes. If the local people could be “civilized” into farming cattle and corn, the idea went, they wouldn’t need to go out into the forest, cutting the trees and killing its animals.

The idea seemed to work at first. Corn and cattle will thrive here for two or three years—at which point the aid workers move on, satisfied with their success. But within five years, it all falls apart. The crops fail, exhausting the soils in which they were never meant to grow, the cattle sicken and die, and the land, spent, may never recover. The destruction spreads like a cancer. Brazilian and American researchers, working under the leadership of American ornithologist Thomas Lovejoy, have found that small cleared patches lose up to 36 percent of their biomass soon after being isolated from surrounding forest, when large trees near fragment edges die. And to continue to farm, the family must cut and burn more virgin forest.

Under the seductive spell of the foreign scheme, the people abandoned their chacras at the edge of the rain forest. Once this land was no longer used, it was up for grabs. The government began to cede these lands, which no one seemed to own, to land-seekers, oil workers, and police. Outsiders burned the land and then brought in hundreds of head of cattle and set themselves up as landlords, or patrones. Lumbermen came from the city to cut the trees. Merchants from Iquitos flooded in to hunt game.

By the time Jim and Richard Bodmer began their studies in the early eighties, most of the local people had all but forgotten the old way of farming. But a few, like Don Jorge, remembered. And they remembered that when the aguaje did not have to compete with other trees for light, when they grew in the fallow lands of the chacras and in the villages, the trees often grew no higher than sixteen feet—short enough that the fruits could be easily harvested without cutting the tree down. The fruits could be plucked ripe, at the peak of their flavor and value, and the tree would continue to produce for decades more.

And so, in March 1992, with $2,500 in funds Jim solicited from the Rainforest Conservation Fund in Chicago, he began the first agroforestry program in South America to concentrate on local, native species.

“We’re trying to instill a pride in methods they already know,” Jim explained later. “We didn’t show anybody how to plant. We worked on a way to use what they already knew.”

Jim is monitoring the 6,000 aguajes that 33 families have planted in their chacras (a number that would swell to well over 7,000 aguajes grown by 54 families by 2008). Tall and thin, his skin growing redder with each hour, Jim works side by side with the farmers, swinging a machete and a hoe under the hot sun, his body covered with mosquitoes. He could be working on forestry in the United States, cool and orderly, as he did for reforestation projects for International Paper. But no; summers he paints houses, and he works here when he can. “My hope,” he says, “is that I can contribute to people here. I have family here. I want to keep working on the aguaje,” he says, “because it would be immoral if I didn’t.” He states this as simply as if he were noting the acidity of the soil.

He is helping other families to experiment with other forest species: the tart, acidic carambola, or star fruit, as well as copuaçu, a fruit the size of an orange that tastes like a mango crossed with a guava that is now in great demand from ice-cream producers in Brazil. Fruits like guanábana, camu-camu, and sapote, as well as medicinal plants, bring premium prices at the market in Iquitos.

The trees thrive in the chacras because they are meant for this place. Many species, like the inga, fix nitrogen in the soil, enriching instead of depleting it. Because the chacras are planted with mixed species, not just rows of one kind of plant, a variety of nutrients are constantly recycled. A chacra of native species produces for twenty, thirty, forty years—possibly more, Jim explained. Because these chacras are planted on fallow land, formerly used to grow manioc and bananas, there is no need to clear wild forest. And should the family eventually abandon the chacra, they leave behind, instead of a charred clearing, a young, mixed forest of native trees.

But they still need the wild rain forest—and the chacras help them to guard it. For, contrary to many environmentalists’ notions, it is not, Jim insists, the local people who threaten the rain forest, but the greed of outsiders whom locals often feel helpless to evict.

“If we don’t protect our resources, who’s going to do it?” Raúl Huanaquiri, the municipal agent, an elected community leader, is speaking to us in Spanish in front of the single classroom of San Pedro’s mud-floored collective school. Around the school stand San Pedro’s wood and thatch houses, perched on stilts at the river’s edge. Once again, as at the wake for Mario’s son, ours is the only canoe with a motor moored to the mud bank.

Raúl stands in front of one of the school’s five green chalkboards, which hangs suspended from bamboo poles lashed together by lianas. Behind him, a map of the reserve, drawn in blue chalk, shows the waterways, the villages, the northeastern frontier of the reserve, near the border with Brazil. The scientists sit hunched in the wooden chair-and-desk sets—just as in elementary school, learning from the teacher in front of the room.

“These people know more about conservation than all the gringos combined,” Jim says as he introduces Raúl. “We have a lot to learn from them—of how to live as a community, as a peaceful, sustainable community, in a peaceful way.”

Jim translates as Raúl, wearing high rubber boots as protection against snakes, explains his neighbors’ understanding of the reserve. “At first when the reserve was created, there was a lot of debate,” he said. “Still two or three people don’t like it. But everyone knows about it now. Everyone realizes we must protect our own resources. We must do it, not the government.”

This the people know well. Last spring, they saw rafts of logs leaving their forest reserve, towed behind big boats from Iquitos. RCF’s site manager, César Reyes, discovered that, despite the law prohibiting lumbering, Iquitos officials had formally granted nine lumber concessions inside Tamshiyacu- Tahuayo—all with official paperwork and with full knowledge of the Peruvian Institute of Natural Resources and the agriculture department. But with César serving as their professional liaison to the authorities in Iquitos, local people protested. The signatures on the official documents allowing the concessions were officially erased, the papers revoked, as if they had never existed. Only forty-eight logs were extracted before the timber concessions were formally annulled.

The people need the forest whole. They depend on it for their lives. Some thirty-five families regularly hunt in the reserve. They take the big rodents like pacas, the piglike peccaries, and occasionally monkeys and larger game like tapir. They eat the smaller animals and sell the peccaries, deer, and tapirs, as well as the pelts, in Iquitos for cash. Thanks to Richard Bodmer’s studies of the populations of wild animals, they realize these resources are vulnerable—not just to outsiders, but to local pressures as well.

So now, before the professors and biologists gathered humbly in the classroom, Raúl outlines some of the changes the people of his village have recently instituted: They have prohibited the hunting of monkeys, giant armadillos, and tapirs, and restricted the take on hoofed animals like peccaries to three animals every two months per family. Locally elected hunting inspectors at two checkpoints along the river register every animal taken from the reserve; only local subsistence hunters are allowed to pass. And although the area is vast, there are no roads, only waterways, so it is difficult to pass unnoticed.

They have organized group work days, or mingas, to plant native trees in the chacras at the western border of the reserve. “The idea also,” he tells us, “is to teach our kids, so in the future, they will know what a white-lipped peccary is, and also know the forest plants.

“With village protection, peccaries and large rodents are beginning to visit us again,” Raúl reports, to murmurs of approval from the Americans. “We are trying to coordinate with other communities.”

In fact, the reserve’s methods were highlighted at a conference sponsored by the Institute of Natural Resources in Iquitos the month before. The agricultural techniques developed for the reserve were adopted for a $5 million, four-year project in Pacaya- Samiria. Jim and César would like to hire two more Peruvian agro-foresters to work in the villages at the reserve’s northern borders along the Yavarí- Miri River. And as Greg, Gary, and Jon discuss later, with another $50,000 they could finally afford to pay their Peruvian site manager, César, what he’s worth, and give Jim, for the first time, a salary.

“The reserve has become an example,” Raúl tells the board as he closes his careful, formal speech. “International people should come to see the reserve, to benefit not just the people here, but the entire country.”

As the information session concludes, from his little desk in the classroom, a professor raises his hand. Jon waits for Raúl to call on him.

“I’m delighted,” Jon says, “to meet such great minds in San Pedro.”

DIANNE TAYLOR-SNOW

The opera house in the jungle, the Teatro Amazonas.

DIANNE TAYLOR-SNOW

The underwater city of Belen.

ANDRESEAL/IMAGEQUESTMARINE.COM

Botos look so unlike other dolphins, but many see in them a strange beauty—the beauty of a creature poised on the brink of becoming something else.

DIANNE TAYLOR-SNOW

The author watching for dolphins.

DIANNE TAYLOR-SNOW

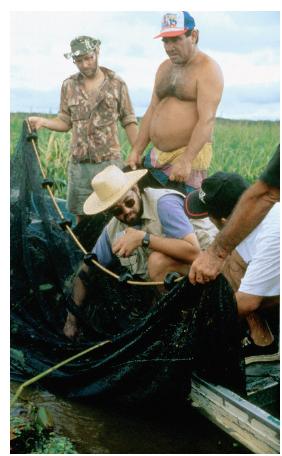

Researchers from INPA discover an eel unknown to science.

SY MONTGOMERY

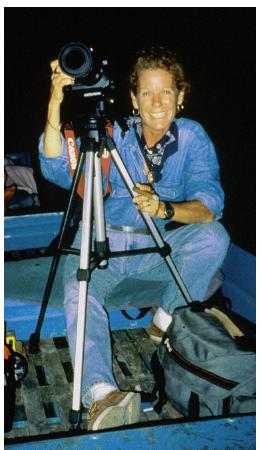

Dianne Taylor-Snow with camera and cigar.

DIANNE TAYLOR-SNOW

The Meeting of the Waters, where dark and light waters flow side by side.

ANDRE SEAL/IMAGEQUESTMARINE.COM

With their wing-like flippers and extraordinary flexibility, pink dolphins can fly through the drowned branches of trees like birds.

SY MONTGOMERY

Time traveler: evolutionary biologist Gary Galbreath.

DIANNE TAYLOR-SNOW

Moises Chavez: our guide on the Tahuayo.

GREG NEISE

While paddling his canoe, Don Jorge Soplin was nearly seduced by a dolphin.

DIANNE TAYLOR-SNOW

A man with a woolly monkey at the Iquitos market.

DIANNE TAYLOR-SNOW

A red uakari monkey.

DIANNE TAYLOR-SNOW

Several fishing spiders, Moises told us, worked all night to create this giant web, which stretches as long as a badminton net.

DIANNE TAYLOR-SNOW

Flooded forest by day.

DIANNE TAYLOR-SNOW

A rare baby tamarin awaits illegal sale in Iquitos.

DIANNE TAYLOR-SNOW

View from up the machimango tree. Below, people are fishing for piranhas.

DIANNE TAYLOR-SNOW

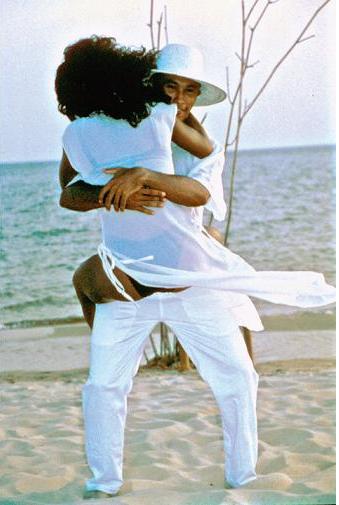

The Dance of the Dolphin: the beautiful girl meets her dolphin lover at the village ball.

ANDY CAULFIELD

At times the botos seem to hang in the water like a sail in the air: weightless, timeless, impossible.