SAUCES, RELISHES, AND PICKLED VEGETABLES (Salsas, Chiles, y Legumbres en Escabeche) 333

BREAD, SWEET YEAST ROLLS, AND WHEAT FLOUR TORTILLAS (Pan, Pan Dulce, y Tortillas de Harina) 365

DESSERTS, ICES, AND SWEETMEATS (Postres, Helados, y Dukes) 391

SEASONINGS AND OTHER COMMONLY USED INGREDIENTS 425 CHILES AND HOW TO PREPARE THEM 459 COOKING EQUIPMENT 485 SOURCES FOR MEXICAN INGREDIENTS 493 METRIC CONVERSION CHART 505 BIBLIOGRAPHY 507

DESCRIPTIONS OF COLOR PHOTOGRAPHS 509

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None of my books could have come into being without the help of many Mexican friends—housewives, cooks, teachers, restaurateurs, scholars, etc. — each of whom has contributed to my culinary education over the years in one capacity or another. A very special thank you to all of them; and to name a few: Hortensia Cabrera de Fagoaga, Ana Maria Guzman de Vazquez Colmenares, Livier Ruiz de Suarez, Maria Dolores Torres Izabal, Margarita Martinez de Porter.

My deep gratitude to my much valued editor and friend, Frances McCullough, who has held my hand through the pangs of book-birth on five occasions; also to the totally (unwittingly) British crew of Michael Calderwood, the photographer, and artist Susana Martinez-Ostos. Also to my painstaking copy editor Chris Benton (non-British). All were a joy to work with. A special thank you to Janet Long-Solis, whose doctoral thesis and subsequent book, Capsicum y Cultura—La historia del chilli, greatly enlightened me (and other recent writers on the subject) on the complexities of the culture and history of that most fascinating of plants.

My congratulations to the designer, Barbara Cohen Aronica, who made visual sense out of a highly complicated manuscript. My thanks and sympathy to my managing editor, Diane Shanley, and to my excellent and sorely tried proofreaders, Margaret Benton and Rose Ann Ferrick. And for all of his help

THE ART OF MEXICAN COOKING

on the botanical details, my appreciation to Alejandro de Avila. 1 would also like to express my gratitude to Harper &. Row for allowing me to use several recipes from my earlier books, albeit in a somewhat modified form.

Finally an acknowledgment of my debt to those wonderful cooks who, if judged by the excellence of their food, should all be published authors: the Annes, Augustins, Frans, Loises, Jerries, and Robertas, for they with others have kept my books alive and thriving. I should like to include for them a quote from Poppy Cannon (in her introduction to Aromas and Flavours by Alice B. Toklas):

“Little by little I began to understand that there can be value in giving a fine performance of another’s compositions . . . that an exquisite interpretation can he in its own way just as creative, just as imaginative as an invention.”

X

INTRODUCTION

f

This book devotes itself to the traditional popular foods of Mexico: those distinctive and delicious everyday dishes that for me sum up this remarkable cuisine. Even five years ago it wouldn’t have been possible to write this book—in terms of the sophistication of cooks and availability of ingredients. I’ve placed special emphasis on the necessity for the right ingredients and how to prepare them using traditional methods. Cooking techniques are not complicated—unlike many of those in the French cuisine, for instance—and they are the result of my 32 years of living, traveling, and learning in Mexico. My teachers have been women and men from all walks of life—some with little formal education—hut who share an immense appreciation of their regional foods and how they should he prepared to bring out the very special flavors and textures that make them authentic. This book does not pretend to be a definitive work, which would require many more years of study and several volumes, but rather a selection of particularly important dishes.

These popular, traditional foods are so regionally diverse, and so varied within those regions themselves, that they defy a cohesive, all-embracing definition. A certain homogeneity has indeed come about through improved transportation and other communications. But the basic differences remain, perhaps more because of the inability to reproduce the same chiles and herbs unique to one area in another (owing to climatic and topographical condi-

XI

THE ART OF MEXICAN COOKING

tions) rather than from the strong dictates of local cultures. They vary in levels of sophistication from those that are wild and gathered at random— often eaten raw—to dishes that call for a number of nonindigenous ingredients requiring more intricate methods of preparation. But while peasants and urban gourmets alike can lick their lips over a snack of grilled grasshoppers or a taco of colorm (coral tree) flowers with a sauce of grilled tunas (prickly pears), the peasants would go hungry rather than eat, say, a crepe of sauteed sweetbreads in a pulque/cream/pasilla sauce, or a chicken breast stuffed with cuitlacoche in a cream of squash flower sauce a la nouvelle. Nor would a Sonorense or Campechana necessarily delight in a chichilo negro from the Oaxacan coast, redolent of charred chiles and avocado leaves.

These foods, most of them unique to Mexico, can be seen at many different levels that do not necessarily coincide with the social or economic conditions of the consumers, and a taste for them varies little between large urban centers, provincial towns, and villages. There are the hunted or gathered wild and seasonal foods that I have mentioned in other books: iguana , armadillo, migrating ducks and doves ( canates and huilotas ), insects like chapulmes (grasshoppers from Oaxaca), jumiles, a type of beetle often eaten alive in Morelos, escamoles (ant larvae) from Hidalgo and neighboring states; colorm (coral) and yucca flowers, flowers and fruits of various cacti, wild greens and herbs like lamb’s-quarters ( quelite cenizo ) and wild anise ( anis del campo) among many, many others.

There are the hearty country meats, most often prepared by local experts on weekends for country markets and for the townsfolk whose dia del campo (day in the country) would hardly be complete without tacos of carnitas ..(browned pork) or pit-barbecued lamb with its accompanying stuffed stomach, montalayo, or pit-barbecued ox head in maguey leaves (picturesquely referred to as rostro, which means “face” or “countenance” in Spanish) with a rustic, rough-textured chile sauce and a bowl of the concentrated juices from the cooking pit.

The early morning brings women to the entrance of the marketplaces or to strategic street corners with their tamale steamers and earthenware pots of atole (corn-based gruel), and later on in the morning those who serve a restorative tripe soup, menudo, guaranteed to cure the worst of hangovers.

Many of the same cooks return later in the day with the street food of the evening— pozole (a pork and hominy soup/stew) or masa antojitos, sopes, quesadillas, enchiladas , etc.—made up while you wait for the charcoal under the comal to settle down to a healthy glow. Next would come the eating stands of the marketplaces with their Jong wooden tables and benches, akin to the cocinas econdmicas, modest little holes-in-the-wall that serve simple comidas to market and office workers and well-dressed aficionados alike. It will

xii

INTRODUCTION

be home-cooked, honest food: rice or pasta soups; unsophisticated stews of chiles, meat, and vegetables; or vegetable fritters in a tomato broth, all followed without fail by some soupy beans. It is the same food that might be served in more affluent homes, where more protein, richer sauces, and the regional touches of the household’s cook would undoubtedly be included.

Tourist hotels are finally catching on, and breakfast and Sunday lunch buffets of regional foods have become commonplace. Banquets for diplomats and other grand occasions have for the most part (with the great exception of those prepared by Seriora Mali Quijano and her famous mother) remained European in content.

Generally, and sensibly, the main meal, comida , is served anytime after two o’clock in the afternoon, after a sustaining mid-morning brunch ( almuerzo ), with a light supper to finish off the day’s eating—a hearty meal of rice and mole would be unthinkable just before going to bed.

The foods of regional Mexico are in a gastronomic world of their own, a fascinating and many-faceted world, but alas, far too many people outside Mexico still think of them as an overly large platter of mixed messes, smothered with a shrill tomato sauce, sour cream, and grated yellow cheese preceded by a dish of mouth-searing sauce and greasy, deep-fried chips. Although these do represent some of the basic foods of Mexico—in name only—they have been brought down to their lowest common denominator north of the border, on a par with the chop suey and chow mein of Chinese restaurants 20 years ago. These dishes can be wonderful when cooked with care and presented in their correct culinary context, but instead, they have been transformed into a cheap culinary “fix.”

On the other hand, to be fair there are some significant, positive changes going on across the United States as a small, but growing, number of specialty restaurants are attempting—and with no small measure of success—to change this image by presenting Mexican regional foods, interpreted in an American or southwestern style, with light adaptations and grilling as prominent features. Perhaps they have found the answer with this happy medium, for it is not always easy or even feasible to present the authentic day-to-day meals of a country and people so different in climate, temperament, and eating patterns from those of the United States, where sophisticated restaurant-goers and food writers are constantly in search of “something new" to satisfy their culinary curiosity. This is great in more ways than one, but I sometimes wonder just how much is being distorted or lost in this enthusiasm for the new 7 . Fredy Girardet says, “We must preserve our regional cuisines because they are our culinary foundations.” And Poppy Cannon, in her introduction to Aromas and Flavours by Alice B. Toklas, notes, “I began to comprehend a little the French resentment against change without reason (italics are mine). It

xiii

THE ART OF MEXICAN COOKING

began to dawn upon me that certain dishes like sonnets or odes cannot be brought into being without obeisance to classic rules and restrictions.” The talented young chefs in America today are creating some wonderful dishes— but also some culinary misalliances with Mexican ingredients. I’m sure it wouldn’t occur to them to put cilantro and jicama into their coq au vin or add pozole corn and cumin to desecrate their bouillabaisses. They’ve studied the French, Italian, and Chinese cuisines seriously but use Mexico’s exciting ingredients without due regard for the traditional cooking processes and balances that make a great Mexican dish, with its many-faceted or layered depths of flavor. It’s this depth and character that I find so often missing in these “new” dishes, and it’s one of the reasons I’ve included detailed instructions on techniques and ingredients. My aim in all my books is that expressed by a Finnish designer, Antti Nurimeineim: “I am interested in continuity and refinement. I want to perfect things, not always to make new ones.”

So often the new dishes hit only the high notes and miss the satisfying complexities altogether. For instance, a blended raw chile sauce tastes blatant, without the subtleties of, say, charring the chiles to round out the flavor. Nor should dried chiles be soaked endlessly or skinned and blended to a smooth, watery liquid. Colorful, yes, but the flavor is unidentifiable. They should be lightly toasted, as a general rule, soaked for the required time, and then blended to a specific texture with other balancing ingredients—without, for instance, the shocks of pineapple juice or chocolate in a table sauce. And cumin! Used in microscopic quantities in some Mexican cooked sauces, as it should be, it is pleasant, but added as it is con bravura in many southwestern-type recipes, it has a sweaty taste. And what about those beans, al dente and saltless to boot? Apart from being very gassy and innocuous, they bring to mind the admonition in a little cookbook written to the campesina (countrywoman): “If you eat beans, they should be well cooked and with salt.” (And it also gives this advice: "A little pig will bring pleasure to your home.”)

It is heartening to see the great increase in the availability of ingredients for these and other regional recipes across the country. Of course, the Southwest—especially California—and the Chicago area, still lead the way, catering to their large Hispanic populations. But to see a new food chain like the Tianguis markets in California (of Von’s parentage), for instance, devoting itself to the needs of those populations, with an increase in the variety of chiles, fresh produce, and staples, is a “happening” in the world of food. It will also make a large proportion of these recipes cookable; a few may be more difficult to reproduce but not to the aficionado, who in my experience will beg, borrow, grow, or mail-order in order to re-create faithfully the authentic flavors of this compelling and addictive food. I have no doubt that letters will soon be arriving to tell me about flourishing hoja santa bushes, American

XIV

INTRODUCTION

sweet potatoes being sun-seasoned in the Mexican style, or some little tricks to cultivate epazote the year round—not to mention the discovery of a homespun corn grinder for the nixtamal. It is for them and the other aficionados of honestly authentic Mexican food—wherever they may be in the world— that I have written this book.

NOTE ON COOKING TIMES

The cooking times given in the following recipes should be considered an approximate guide since actual cooking times will be influenced by a number of factors. Food cooks faster on a professional range or heavy counter-top burners with the same high gas pressure than on an ordinary domestic stove. Heavy pots and pans will transmit the heat more efficiently than lighter ones, while wider pans will reduce sauces faster than deep, narrow pans. Altitude is also important, since of course liquids boil at a lower temperature the higher the altitude.

In Mexico these factors also apply, of course. Mexican meat and poultry tend to be more compact than their American counterparts, so cooking times should be extended by about one third to one half.

NOTE ON SPANISH AND ENGLISH TRANSLATION

Although it’s inconsistent, for the sake of clarity and easy reference, in the recipes the Spanish title appears first while in all other cases the English appears first.

XV

CORN

(M aiz)

“With each rising of the sun man became more like the corn and with each moon the corn became more like man; and both began to take on the likeness of the Gods. ”

TORTILLAS AND TORTILLA DISHES

Tortillas de Mai'S (Corn Tortillas)

Lime (Cal)

Preparation of Dried. Corn and Making of Masa Equipment for Making Corn Tortillas The Tortilla Press The Corn Mill The Comal (Griddle)

Tortillas Made with Prepared Masa Tortillas Made with Quaker Masa Harina Methods for Reheating Corn Tortillas Totopos Fritos I (Fried Tortilla Pieces)

Totopos Fritos II (Fried Tortilla Pieces)

Totopos Salados y Fritos (Fried Salted Tortilla Pieces) Totopos Tostados (Crisp Baked Tortilla Pieces) Tostadas (Fried Whole Tortillas)

Raspadas (Thin, Crisp Tortillas)

Tortillas de Mai'z y Trigo (Corn and Wheat Tortillas) Enchiladas Placeras (Enchiladas Served in the Central Plaza) Enchiladas de Santa Clara Enchiladas Verdes (Green Enchiladas)

Enjococadas I (Tortillas in a Sauce of Cheese and Cream) Enjococadas II (Casserole of Chicken Tacos and Green Sauce) Salsa Verde (Green Sauce for Enjococadas II)

Tostadas de Apatzingan Flautas de Guadalajara Fillings for Flautas Polio Deshebrado (Shredded Chicken)

Rajas de Chile Poblano (Poblano Chile Strips)

Papas Guisadas (Potatoes with Tomatoes)

Picadillo Blanco (Ground Meat)

Tacos de Requesdn (Ricotta Tacos)

Efigenia’s Chilaquiles Chilaquiles de Tequila

Tortillas con Asiento (A Oaxacan Tortilla Snack) Enfrijoladas (Tortillas in Bean Sauce)

Entomatadas (Tortillas in Tomato Sauce)

Papadzules (Tortillas in Pumpkin Seed Sauce) Cross-reference:

Chilaquiles Tacos de Polio

Tortillas de Harina (Flour Tortillas)

“There was an intimate relationship between the Otomis (known as the Men of Corn and the first inhabitants of the central highlands of Mexico), a dependence, a symbiosis, a living together with bonds of affection between these two living beings: man and plant. Both grew on this earth to provide for one another: man laboring, planting, irrigating, and fertilizing the com. The com providing man with tortillas, tamales and atole.”

I

.1. t you have lived in Mexico as many years as I have, you will agree, romantic as the notion is. It is particularly true in the case of the small farmers, whose lives and activities center around the cultivation of their corn—even if it is just enough for the family’s consumption, para el gasto, as they put it. Planting, except in the case of nonseasonal irrigated corn, begins just before the rains start toward the end of May. Then the first longed-for rain eventually falls, and the corn sprouts and grows; there is the first weeding, la descarda, to be done. As the rains continue and the corn grows apace, new weeds spring up and thicken around the base of the corn, and the segundando, the second weeding, takes place. It is a backbreaking job for the laborer, who squats with his knees almost up to his chin, coaxing out the weeds with the tip of his curved machete so as not to hurt the young com plant. Then there is the fertilizing and afterward the anxious watch for mealybugs that burrow through the heart of the sprouting ears, until the first tender elotes (ears of corn) begin to form. In their green husks they are sold to be roasted over charcoal or the kernels shaved off for the fresh com tamales or atole (gruel). The corn silk is dried and made into a tea used as a remedio for the kidneys; the long, dark green leaves are cut from the stalk for wrapping the intricately bound corundas (triangular tamales in Michoacan); the plumelike flower at the top of the plant is shaken and the seeds collected to be toasted and ground for tamales de espiga (a specialty of eastern Michoacan), while the bulbous, silvery-skinned mushroom cuitlacoche that sometimes grows on the ears provides an epicurean treat.

THE ART OF MEXICAN COOKING

Then comes the long wait throughout the autumn as the corncobs dry out on the stalk. If the rains continue, the stalks are bent over so that the water will run from stem to tip of the fully sheathed corn husks. The dried ears of corn are harvested at the beginning of December, a time when the whole family will turn out with hemp slings over their shoulders in which to collect them. Once the corn is stored in rustic bins made of dried reed, the work is almost finished except for cutting and raking in the dried cornstalks for fodder for the cattle. According to the village or region, each and every one of these stages will be marked with a ceremony—blessing the crops, scaring away evil spirits, exhortations for rain, blessing the new corn, and then the harvest—all of them rooted in the pre-Hispanic customs and beliefs of the past.

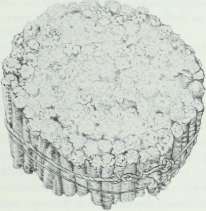

As work in the field slackens, the dried grains of corn are shaved from the cobs (one of the most rustic but efficient instruments for this shaving is the elotero illustrated on page 29, made up of tightly packed and tied old dry corncobs; I am told that it lasts for years) and stored in bags until needed for the next batch of tortillas. And as spring approaches, the stubble is burnt to ashes, the land tilled and left fallow until the advent of May, when the cycle begins all over again.

All kinds and colors of corn are grown, depending on local preferences and prejudices, climate and soil. Cachuazintle, broad white hominy (confusingly in Michoacan there is a small brownish com that goes by the same name), is used for pozole, or tamale flour. There are the medium-sized ancho (broad) corn and punteado, shaped like a thin, tapering tooth. All colors of the rainbow are represented: creamy and canary yellow, mauve, mulberry, greenish, or bluish-black (prieto). There is corn of variegated colors called pinto, and there are many shades in between. There is a plentiful choice for making exotic-colored tortillas and atoles. (These are not always in favor; I know of a small country restaurant near Jungapeo where capitalinos, people from Mexico City, walk out when they see tortillas of these multicolored corns, favoring the whitish, clean look of the ones they are expecting— although ironically the Mexico City tortillas are a dirty yellow, tough and leathery in contrast to Don Ignacio’s tender handmade ones.)

To sum up, the cooking of corn in Mexico with all its elaborations and ramifications is, and always has been, within the realm of the highest culinary art, beyond that of any other country.

CORN

TORTILLAS DE MAIZ (Com Tortillas)

“The tortilla would puff up as if alive, as if it wished to fly, as if Ehecatl [the Aztec God of Wind] had blown into it himself.”

Salvador Novo

I wrote at some length in The Cuisines of Mexico about the history and regional differences of tortillas (there are about 30 types in Oaxaca alone, according to the latest research on the subject), so I will not dwell on these aspects here. Suffice it to say that the corn tortilla was for centuries, and still is in the country areas, the sustaining bread of the Mexican people, with the exception of those in the northern states. In The Tortilla Book I mentioned its versatility: a wrapper for countless ingredients— tacos and enchiladas; a pasta— chilaquiles and dry soups; a scoop— totopos; a plate—a tostada; dried and ground to a flour, it is re-formed and made into antojitos or small balls for soups, to mention just a few of its uses.

The simplest food is always the most difficult to prepare, for there are no predominant flavors to mask bad or indifferent ingredients or the careless handling of those ingredients. The corn tortilla provides the best example of this idea that I know. The ideal tortilla is made of carefully selected dried corn; just the right amount of lime (calcium oxide) should be added to the cooking water—too much will make for a dull yellowish, bitter-tasting tortilla with an acrid smell. If the com is left too long over the heat, the dough will be sticky and impossible to make into tortillas.

Without doubt, a hand-patted tortilla is the best; it is soft-edged and tender. But as I have written elsewhere, the patting out of tortillas is a dying art, so one has to opt for the next best: those pressed out individually with a tortilla press and then cooked if possible on an earthenware comal (bakestone) over a wood fire. (I have described the alternative methods on page 11).

A superbly made tortilla almost melts as you bite into it and when properly stored lasts some time without drying out. But the perfect tortilla is hard to come by nowadays, even in Mexico City, let alone in the United States. In my teaching travels in the United States recently I have seen some excellent tortillas, especially in California, Detroit, and Chicago, and while Texas (particularly Houston) is improving, Arizona and the South still have a long way to go.

THE ART OF MEXICAN COOKING

WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN A GOOD TORTILLA

It should be of white corn (let’s forget blue for the moment), opaque, mealy, neither too thin nor too thick, and speckled with brown to give some indication that it is cooked (many look half raw).

TYPES OF TORTILLAS TO AVOID

• The much-touted American handmade ones (from San Francisco and elsewhere) that are far too thick and clumsy.

• Those dirty-yellow, bitter-smelling ones. Too much lime has been added to the cooking water.

• Tortillas that are too thin, transparent, and chewy, which means that wheat flour has been added to the masa.

• Tortillas made of blue cornmeal that crumble at a glance. The corn for the cornmeal has not been treated in an appropriate way for making tortillas.

• Frozen tortillas that turn out to he as stiff as cardboard.

With these criteria in mind, there are multiple good choices.

CHOICES OF TORTILLAS

• Buy good frozen tortillas (avoid those with additives).

• Buy good packaged tortillas from a supermarket or tortilla factory if you live in an area with a Mexican population.

• Buy frozen masa, now widely available in many Mexican markets, and make your own.

• Buy fresh masa from a tortilla factory and make your own.

• Buy dried corn and make your own nixtamal for the tortilb factory to grind and make your own tortillas.

• Do the above hut grind it yourself.

• Use Quaker Masa Harina, mix with water, and make your own.

Note: If you are buying fresh masa and making your own tortillas, the masa will probably be sold to you still hot in a tightly tied plastic bag. Undo it as soon as possible. Set aside what you want to use right away, divide the rest up into, say, four portions, weigh each portion, form into a flat cake (more convenient for storing), and wrap for the freezer with the weight clearly marked on it. Fresh masa tends to sour if left in the refrigerator for more than a day or two.

A final note: Sour masa will not hurt you. It just has a vaguely unpleasant taste and smell.

CORN

Lime (Cal)

This chemically pure lime, calcium oxide, is used in the preparation of dried corn for making tortilla and tamale dough. It is generally sold in rocklike lumps of varying sizes. To use it in this state, break off a piece about as large as a golf ball (once you have some experience you can estimate more accurately) and crush it down as much as possible. Sprinkle well with cold water. It will then start to slake, or burn as the Mexicans say, and it does just that. It starts to crumble with a slight sizzling noise, sending off a vapor. If you put your hand over the bowl you are using, you can feel the heat emanating from it. When the action has subsided, it is now slaked; stir again and pour the milky liquid through a strainer into the pot with the com and water (page 8). Take a taste of the water; it should have a slightly acrid taste or, as the Mexican expression goes, “grab your tongue.” If the water is very strong and bitter, add more cold water to dilute the corn water. If it is too weak, pour more water through the strainer containing the lime residue and try again.

Since one usually buys lime by the pound at the very least, it can be broken up into smaller pieces and stored in closed jars, but with time it will naturally slake on its own with the natural moisture in the air. It is still usable, although it will have broken down to a powder containing some small lumps. When you add water to it for the nixtamal, it will not burn.

Note: When handling lime, be careful not to get any near your eyes and always use a noncorrodible container for diluting it.

THE ART OF MEXICAN COOKING

Preparation of Dried Corn and Making of Masa (Nixtamal y Masa de M ai'z)

Nixtamal is the name given to dried corn kernels that have been cooked in a solution of lime and water. After this step, the kernels are ground to a fine dough called masa that is ready to be made into tortillas, antojitos, or some tamales.

CHOOSING THE CORN

When buying dried corn of whatever color or size, always make sure that it is not picado (perforated) by weevillike insects that burrow into the kernels, eating the starchy content inside. If the corn is already packaged, you can easily see this by a powdery residue at the bottom of the hag.

The kernels should he free of any musty odor—such an odor indicates that it has been stored in a damp place—which will affect the flavor of the tortillas.

PREPARATION

MAKES ABOUT 2 POUNDS OR PA CUPS MASA

1 pound (2V2 cups) dried com kernels

1 cup water

2 rounded teaspoons powdered lime (see page 7)

First run the dried corn kernels through your hands to pick out any small stones, pieces of chaff, etc. Rinse thoroughly in cold water and drain.

Put the rinsed corn into a pan and add enough water to come at least 1 inch above the surface of the corn. Stir 1 cup of water into the powdered lime (he careful of your eyes; it burns) and pour the mixture through a fine strainer into the pan, pressing out any soft lumps with the back of a wooden spoon and discarding the hard residue. Stir the corn well.

Set the pan over medium heat. As soon as the mixture heats up, the outer skin of the corn kernels will turn bright or dull yellow, depending on how much lime is used. Cook until small bubbles appear on the surface—the mixture should not boil. Lower the heat and continue cooking until the yellow skin can easily he sloughed off the kernels—test by rubbing a few kernels between your fingers. This should take about 15 minutes more. Set the corn aside in the warm liquid for at least 12 hours and up to 48. Drain, rinse in cold water—it is not necessary to rub off all the skins for this type of

CORN

masa —and send to the mill to he ground (see page 10 for additional information on grinding utensils).

The important thing to look for when making your own nixtamal is that the corn should not be overcooked, or it will make a tacky masa, practically impossible to handle for making tortillas.

Equipment for Making Corn Tortillas

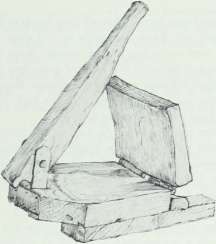

TORT/L L A PRESS

The natural tortilla press is, of course, the hands, but the art of patting out a tortilla is dying. The second method, also handmade, is on the wane, too, except for a few isolated places in the low hot country. A ball of masa is pressed onto a piece of banana leaf—which has now almost totally given way to plastic—and patted out with one hand while the other turns the leaf in circular fashion to ensure that the tortilla will be round. Both these methods are rapid and carried out with amazing dexterity.

But with the modem age has come the tortilla press. The wooden press (illustrated on page 7) is certainly picturesque but is also clumsy and tends to slide around. By far the most efficient is the heavy cast-iron press made in Mexico; these vary in size—from 6 to 7 inches in diameter is a good size for general use. Care needs to be taken as they tend to rust, despite their noncorrosive paint finish. They need no curing, just a rinse. Be sure the plates are thoroughly dry before making the tortillas; you will also need a plastic liner for each plate so that the masa does not stick to the metal. The smallest (1 quart, although it seems too small) Alligator Baggie is my choice hands down—no zips and locks and fancy flaps. After being used (think ecologically) they can he wiped clean, folded, and stored with the press. After you use it, the press should also be wiped clean and dried thoroughly; place

THE ART OF MEXICAN COOKING

paper toweling between the plates to prevent any moisture from forming and corroding the metal.

There have been a couple of fancier presses made in the United States— one elegant enameled heavy one that seems to have faded from view and a sleek, light aluminum one, easy to clean but too light for the job, which tends to snap under heavy pressure.

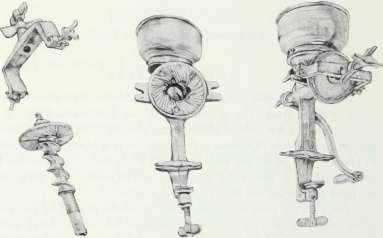

CORN MILL (MOL I NO DE MAJZ)

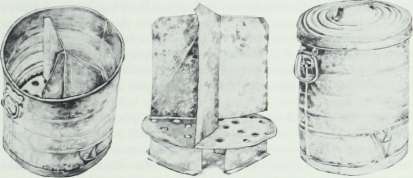

In Mexico the only corn-grinding utensils for centuries were the black basalt metate (grinding stone) and the mano or metlapil (muller). Of course they are still used today in remote villages or when the electricity fails at the local country mill. The mxtamal is stone-ground at the country mill, although I have noticed some places in the southeast of the country where the mill is of metal—the resulting masa is much coarser.

There are now small tortilh factories almost everywhere in the United States—there is even one in Alaska—and it is possible to go and buy masa if you want to make your own tortillas. However, for the dedicated do-it-yourselfers there are alternatives. You can prepare your own nixtamal (see page 8) and take it to the tortilla factory. Or you can buy a grinder like the one illustrated and grind your own corn. For that you must tighten the blades as far as possible, and even then the masa will be fairly coarse. This last method will require patience and a very strong arm.

CORN

COMAL OR GRIDDLE

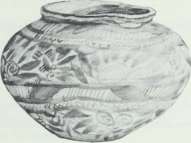

The comal (the name comes from the Nahuatl word comalli) is a thin, circular “griddle” used for cooking tortillas. There are several types to choose from, as well as substitutes, depending on what is available where you live (if you travel to Mexico unencumbered, you can always bring the real thing back with you) and what sort of cooking facilities you have.

The traditional comal, still used in the villages for cooking over wood or charcoal (I use it over gas), is a disk of thin, unglazed earthenware. Before being used it must be cured, or the tortillas will stick to it. Dilute some powdered lime with cold water and stir to form a thin paste. Spread the cooking surface of the comal with a thick coating and place over the fire. When the white lime turns a cream color after it has dried out, brush off the excess powder, and the surface will be ready for cooking tortillas. Every time you want to use this type of comal for tortillas or masa antojitos the process will have to be repeated.

A heavy tin or light metal comal is the most commonly used in Mexico, often made with the recycled lids of old oil drums. It can be used over any type of fire, although it tends to warp when used over an electric burner. The advantage of this type of comal over the others that follow is its thinness, so that the heat cooks the dough fast, an important requisite for a tender tortilla. And also the heat can be adjusted quickly. A light rubbing with oil is all the curing that is needed. It can be washed with soap and water if messy, and any substances sticking to it can be scoured with a pumice stone. The important thing is to dry this comal thoroughly after washing as it rusts easily. A heavy iron griddle can be used quite successfully over gas or electricity, but it takes longer to transmit the heat to the dough, and the heat is not as easily controlled. Follow manufacturer’s instructions for curing.

A heavy frying pan with a black surface could be used, but you can burn your hands on the hot sides and the high heat will probably spoil the pan’s surface.

If you have one of those glass-topped stoves, you can make tortillas right on the surface, although 1 don’t know whether the manufacturer would approve!

For making good tortillas the surfaces to avoid are those highly polished metals—aluminum, stainless steel, Teflon, etc.—that reflect the heat. Your tortillas made in them will tend to be dried out, pale, and underdone.

Making a Tortilla by Hand

Knead the masa well until it is completely smooth. Moisten your hands with water. Take a small piece of dough and roll it into a ball about V /2 inches in diameter. Press it out a little between your hands and then begin

THE ART OF MEXICAN COOKING

patting it out and extending it with each pat first on one palm and then the other, turning your hands over as you do so, until you have a thin disk of masa with a smooth circumference, about 5 inches in diameter. (It takes about 33 pats to extend it, I am told—although I always lose count.)

TORTILLAS MADE WITH PREPARED MASA

MAKES 15 5-INCH TORTILLAS

1 V 4 pounds (about 2V 2 cups) prepared com tortilla masa (page 8), approximately water if needed

If the tortilla masa has been freshly made, it will probably be the right consistency for working immediately—a soft, smooth dough. If the masa has been sitting around and drying out a little, then add a very little water and knead until it’s smooth and pliable, not the slightest bit crumbly.

Divide the dough into 15 equal parts (each one should weigh just over 1 ounce) and roll into smooth balls about Wi inches in diameter. Place all but one of the balls under plastic wrap so that they do not dry out.

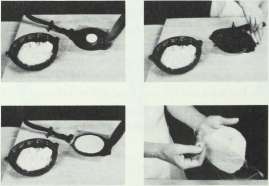

Heat an ungreased comal or griddle over a medium flame. Open up the tortilla press and place a small Alligator Baggie on the bottom plate. Place a ball of the dough on the bottom Baggie, a little off center toward the hinge rather than the pressing lever (it presses too thin on that side), and press it out with your lingers to flatten a little. Cover with the second Baggie and

CORN

press down firmly but not too fiercely (or the dough will be too thin and you will never be able to pry it off the Baggie in one piece). Open the press, remove the top Baggie, lift the bottom Baggie up in one hand, place the dough onto the fingers of your other hand, and very carefully peel the Baggie off the flattened dough. Do not try to peel the dough off the bag. Keeping your hand as horizontal as possible, lay the tortilla flat onto the comal. There should be a slight sizzle as the dough touches the surface of the comal. Leave for about 15 seconds; the underside will have opaque patches and be slightly speckled with brown. Flip the tortilla over onto the second side and cook for a further 30 seconds; the underside should now' be opaque and speckled. Flip back onto the first side again and cook for 15 seconds more. If you have done all the correct things and the comal is the correct heat, the tortilla should puff up, showing that the extra moisture has dried out of the dough. If the tortilla doesn’t puff up and it’s necessary in order to make panuchos, for example, then press it gently on the last turn with your fingers or a towel.

As the tortillas are made, they should be placed one on top of the other in a basket or gourd lined with a cloth to preserve the heat and keep them moist and flabby. They can also be wrapped in foil packages and frozen.

TORTILLAS MADE WITH QUAKER MASA HARINA

MAKES ABOUT 15 5-INCH TORTILLAS

2 cups (IOV 2 ounces) Quaker Masa Harina 1V 3 cups water, approximately 2 1-quart Alligator Baggies for pressing tortillas

Mix the masa hanna with the water and work well so that it is evenly distributed through the flour and forms a cohesive mass when pressed together. The dough should be of medium consistency, neither too firm nor wet and sticky.

Follow the instructions for making tortillas in the preceding recipe.

THE ART OF MEXICAN COOKING

Methods for Reheating Corn Tortillas

If you are cooking on a gas range or a wood or charcoal fire, simply throw the tortilla onto the grill and heat for a few seconds on each side. They may char a little, hut no matter—it adds great flavor and couldn’t be more authentic. But serve immediately; these won’t hold.

For a gas or electric range, wood or charcoal fire: heat a comal over the fire, place tortillas on it, and reheat for a few seconds on either side. Serve immediately, or they will harden.

If the tortillas have been made ahead, wrapped in foil packages, reheat them for about 20 minutes in a 325° oven. Or reheat them in a microwave oven: place a dozen or so in plastic wrap and heat for 30 seconds (approximately, as each oven varies), turning the package over and heating for another 30 seconds. Timing will also depend on the thickness of the tortillas.

If you are using frozen tortillas , it is better to defrost them first and then reheat them in one of the ways suggested above.

To add a little folklore to this more technical advice: I like to heat a pile of tortillas, en famille of course, following the method taught me by a Mexican artist/craftsman, Feliciano Bejar:

TO REHEAT A SMALL PILE OF TORTILLAS

This is the “kitchen” way of reheating tortillas, which can be done over a gas or electric burner or over an open grill. If they char a little around the edges, no matter; that adds flavor.

Place a tortilla on an open burner to heat for about 5 seconds (longer if it is a thick one) and turn over, putting another one on top; leave for a further 5 seconds, turn both over together, and place another one on top, continuing until the whole pile is heated. Wrap in a cloth and bring to the table.

A friend and great cook from Hidalgo, Senora Lara, once after a meal presented her guests with crisped tortilla halves sprinkled with salt. “Even if you think you have no room, eat it; it aids the digestion,’’ she said.

CORN

TORTILLA RECIPES

Tortilla Pieces (Totopos)

TOTOPOS FRITOS I (Fried Tortilla Pieces)

Small fried squares of dried corn tortillas , totopos are sometimes used as a crisp topping for a bowl of soup. In Mexico, they are used for frijoles puercos (page 181—Michoacan version) and Michoacan chilaquiles (page 31). They can also be tossed into a salad just before serving, added to melted cheese dips, scrambled with eggs, or just served by themselves as snacks. You can also make delicious totopos from whole-wheat flour or a mixture of com and wheat totopos (pages 17 and 18).

It is best to use a thin tortilla for totopos. Stack about 4 of them together and cut off the curved parts to form a large square. Then cut them again into small squares, about Vz inch. Spread them out on a rack to dry, in the sun, in an airy place, or, if you are in a hurry, in a 325° oven for about 40 minutes.

Heat about Vz inch of oil in a small pan (a large one uses too much oil) and fry the tortilla squares a few at a time—they will fry more evenly and more quickly if you don’t overcrowd the pan. Turn them over from time to time until they turn a deep golden brown—about 3 to 4 minutes (depending on the thickness of the tortilla). Transfer with a perforated spoon, briefly holding them over the pan to drain off some of the oil, to a double layer of paper toweling. Strain the oil and store in the refrigerator for another use.

When the totopos have cooled off, they can be used as suggested above; any left over can be frozen in an airtight container. Although they will remain crisp in the freezer, they need a little freshening up to look shiny and appetizing. There is no need to defrost them. Either heat them for about 5 minutes in a toaster oven or heat them in an ungreased frying pan with a lid so that you can toss them for a few seconds over fairly high heat.

TOTOPOS FRITOS II (Fried Tortilla Pieces)

When you’re presenting a large bean roll or dip, the totopos should be triangular to act as scoops. Cut each tortilla into 6 triangles and follow the procedure above.

THE ART OF MEXICAN COOKING

TOTOPOS SALADOS Y FRITOS (Fried Salted Tortilla Pieces)

If you wish to have salted totopos, make a solution of salt and water— about 3 tablespoons salt to 1 cup water—stirring until the salt has dissolved. Quickly submerge the tortilla pieces in the water, strain and shake well, and then immediately throw into very hot oil. It splatters a lot and no doubt breaks down your oil—hut it is for a good cause.

TOTOPOS TOSTADOS (Crisp Baked Tortilla Pieces)

If you wish to cut down on your fat intake, then prepare the totopos by toasting, not trying, the dried tortilla pieces. Cut the tortillas into the required size, dry them off, then crisp them and let them brown slightly in a 325° oven for about 40 minutes, turning them over from time to time. Cooking time will depend on the thickness of the tortillas.

TOSTADAS (Fried Whole Tortillas)

Tostadas, often erroneously called chalupas in the Southwest, are corn tortillas that have been fried flat until crisp. They are then topped with various ingredients dictated by regional likes and dislikes. It is best to have a not-too-thin tortilla for these, or your tostada may collapse at first bite and the topping fall all over the place. Oil to a depth of l A inch in the pan should be sufficient to fry the tostadas. They are pan-fried, not deep-fried, until crisp and a deep golden color. They should he eaten as soon as possible after frying; if not, they can be reheated in a 350° oven on a paper toweling-lined tray that will absorb some of the excess oil.

RASPADAS (Thin, Crisp Tortillas)

The raspadas of Jalisco, the totopostes of Chiapas, and the t layudas of Oaxaca all have one thing in common: while of slightly different sizes, they

CORN

are large, almost transparent, crisp-dried tortillas. In this condition they can he stored indefinitely and carried on long journeys, ready for toasting or frying to accompany a meal.

The raspadas are made in an interesting way. The cook begins by making a 6-inch tortilla in the normal way; she then lets it dry out, rather than take on color, on a huge, thin metal hot plate heated by gas. After about 2 minutes the bottom of the tortilla is dry enough for the uncooked top layer to be scraped off. This she does with a length of ‘/ 2 -inch metal tubing. As the dough is scraped off it forms a wrinkled oval shape referred to as a pachola — the same name given to the ground meat patties that are rolled off the metate. (You may wonder what happens to those uncooked layers of dough: in Tequila, there is always a pig or two hovering in the background to absorb that waste.)

The thin raspadas are now completely dried off on the second side, again without browning, for about 30 seconds. They are then cooled off and sold in the hundreds to the restaurants of Guadalajara and even sent far afield to homesick Jaliscienses.

TORTILLAS DE MAIZ Y TRIGO

(Corn and Wheat Tortillas)

MAKES ABOUT 11 5-INCH TORTILLAS

A considerable amount of wheat is grown in the colder central highlands of Mexico, and often in country marketplaces there you can find tortillas made with com masa mixed with an equal proportion of wheat. There is some debate as to whether this came about from taste or necessity, to spin out the com toward the end of the season, when it becomes infected with weevils. This mixture makes a slightly heavier-textured tortilla with an excellent taste.

Wheat that has been picked over and rinsed well is then sent along with the nixtamal (the corn cooked in lime water) to the mill, and they are ground together to make a fine masa. Since very few people have a mill that will crush the com and wheat together in a wet mix, or access to one, I have given an alternative method that works very well.

It is best to try to buy a rather roughly ground whole-wheat flour for this recipe—certainly not a brown pastry flour for instance.

You will need to press the dough harder in the tortilla press than for normal com tortillas; cooking time will be slightly longer as will reheating time.

THE ART OF MEXICAN COOKING

When you’re cooking the tortilla on the comal, the wheat in the dough tends to stick, so it may be necessary to grease the comal very lightly.

Vz pound (about 1 cup) prepared com tortilla masa (page 8)

% cup whole-wheat flour (see note above)

3 to 4 tablespoons water

Mix all the ingredients together and work well so that the flour is distributed evenly through the masa. The dough should he smooth hut fairly firm and pliable—add a little extra water only if necessary to obtain this consistency.

Cover the dough with plastic wrap and set aside for the wheat particles to soften for at least 2 hours in a cool place. If the weather is hot and humid and you are leaving it for a longer resting period, refrigerate the dough. But always bring it up to room temperature before making the tortillas.

Follow the instructions for making corn tortillas (page 12), but increase the cooking time by about 1 minute on each side and add a few seconds on the final turn.

Note: If you are starting from scratch with access to the right type of mill, prepare 1 part com and 3 /t to 1 part wheat berries.

Enchiladas

There are two main methods for cooking enchiladas: (1) frying the tortilla lightly, dipping it into a warm cooked sauce, filling, and rolling; (2) dipping a tortilla into a raw sauce, frying it, then filling and rolling. Detailed instructions for both methods are given in the following recipes.

CORN

ENCHILADAS PLACERAS

(Enchiladas Served in the Central Plaza)

SERVES 4 TO 6

These little enchiladas are served every evening in the main plaza of Xicotepec de Juarez in the northern part of the Sierra de Puebla that adjoins the state of Veracruz.

Traditionally a serving consists of 4 small—about 3 Vi-inch-— -tortillas. The tomato sauce should be of a consistency that thinly covers the tortillas. While the dish should he eaten the moment it is assembled, the component parts can he prepared ahead.

These enchiladas are sometimes filled with refried black beans instead of shredded meat, a good vegetarian dish.

Vi cup, approximately, melted lard or safflower oil for frying

16 3V2 -incfi or 12 4V 2 to 5 -inch com tortillas

m cups salsa de jitomate, Sierra de Puebla (page 339), hept hot

1 cup res desbebrada for Salpicon (page 298), hept hot

V* cup finely chopped w hite onion

(4 cup finely grated queso ariejo or Romano cheese

Have ready a tray lined with paper toweling.

Heat a little of the lard to cover the bottom of a frying pan and fry 2 of the tortillas at a time for about 5 seconds on each side, adding more lard as necessary. They should not become crisp around the edge; drain on the paper toweling.

Immerse the tortillas in the hot sauce for a few seconds. Fill each one with a scant tablespoon of the shredded beef, roll the tortillas up, cover with a little of the sauce, sprinkle with onion and cheese, and serve immediately.

THE ART OF MEXICAN COOKING

ENCHILADAS DE SANTA CLARA

SERVES 4 TO 6

This is one of many recipes given to me by Senora Hortensia Fagoaga. Although born in the Sierra de Puebla, she has had the opportunity of living in many parts of the republic and is keenly interested in good regional Mexican food. She has exceptional sazon (flavoring), as the Mexicans say, and has generously allowed me to cook with her and eat with the family on countless occasions.

The origin of the recipe is unknown, and she is not sure to which Santa Clara it refers.

While the sauce could be prepared ahead, the enchiladas should be eaten as soon as they are ready, or they will become soggy.

4 chiles anchos

1 cup water, approximately

1 garlic clove, peeled and roughly chopped

1 rounded teaspoon (or to taste) sea salt

2 large eggs

V2 cup, approximately, melted lard or safflower oil for frying

12 4% -inch com tortillas

V 2 pound queso fresco or a substitute (see pages 445—447), cut into 12 slices about inc hth icb

Have ready a tray lined with a double thickness of paper toweling.

Remove the stalks, if any, from the dried chiles , slit them open, and remove seeds and veins. Toast the chiles lightly by pressing them down onto a warm comal; the inside surface will turn an opaque tobacco brown. Remove and allow to soak in hot water for about 15 minutes or until reconstituted hut not mushy.

Put 1 cup of water, the garlic, and the salt into a blender jar and blend until smooth. Transfer the chiles to the blender jar with a slotted spoon and blend until the sauce is absolutely smooth—about 8 seconds. Break up the eggs with a fork and stir them into the sauce.

Heat enough of the lard to cover the bottom of a small frying pan. Before you begin frying, make sure that the oil is at medium heat; if it’s too hot and smoking, then the chile sauce will burn.

Dip one tortilla at a time into the chile sauce to cover it thickly and fry for about 10 seconds on each side. Using tongs and a spatula, carefully remove

CORN

the tortilla from the oil and drain on the paper toweling. The egg /chile sauce will look uneven and lumpy (that’s okay; all the more appetizing). Place a slice of the cheese on one side of the tortilla and double over—the cheese should begin to melt with the heat of it. Continue with the rest, adding lard as necessary and working as fast as you can, and serve immediately. Although the enchiladas are traditionally served alone, you could accompany this dish with a lightly dressed tomato and lettuce salad.

ENCHILADAS VERDES (Green Enchiladas)

SERVES 4 TO 6

Although there are many versions of this dish with slight regional differences, this recipe is more typical of the central area of Mexico, in and around Mexico City.

Although traditionally eaten at suppertime, enchiladas in fact make a great lunch dish accompanied by a salad, or with a light appetizer—like ceviche — they make a substantial main course for dinner.

Enchiladas without exception must be eaten the moment they are assembled, or the tortillas tend to become soggy.

THE SAUCE

1 pound (about 22 medium) tomate verde, busks removed, rinsed

2 chiles serranos, stalks removed, rinsed

1 garlic clove, peeled and roughly chopped 1 tablespoon lard or safflower oil A cup chicken broth sea salt to taste

THE REST

Vi cup safflower oil, approximately, for frying 12 com tortillas

IV 2 cups polio deshehrado para tacos (page 218) y 2 cup finely chopped w hite onion V 2 cup creme fraiche or sour cream % cup queso fresco

Have ready a warm serving dish into which the enchiladas will just fit in one layer, or individual plates, and a tray lined with paper toweling for draining the fried tortillas.

Put the tomate verde and fresh chiles into a saucepan, barely cover with

THE ART OF MEXICAN COOKING

water, and bring up to a simmer. Continue simmering until the tomates are just soft—about 8 minutes. Remove from the heat, drain, reserving l A cup of the cooking water, and transfer to a blender jar. Add the garlic and reserved cooking water and blend until smooth.

Heat the lard in a frying pan, add the sauce, and cook over medium heat, stirring from time to time, for about 5 minutes. Add the broth and salt to taste and continue cooking until the sauce has reduced to about 2 cups— about 5 minutes more. Set aside, but keep hot while you prepare the enchiladas.

Heat about 2 tablespoons of the oil in a frying pan, immerse one of the tortillas, holding it down in the oil with a spatula for about 1 minute, turn it over, and fry on tbe second side for about 30 seconds—the tortilla should be well heated through but not crisp. Drain on the paper toweling while you continue with the rest of the tortillas, adding more oil as necessary. Dip one of the fried tortillas into the green sauce, spread a little of the shredded chicken across the center, add a sprinkling of onion and a little cream, roll up, and place on the warmed dish. Continue with the rest of the tortillas. Pour the remaining sauce over the enchiladas, spread with the remaining cream, sprinkle with more of the onion and the cheese, and serve immediately.

ENJOCOCADAS I

(Tortillas in a Sauce of Cheese and Cream)

SERVES 6 TO 8

I was introduced to this dish for the first time by a good friend and wonderfully intuitive cook, Senora Livier Ruiz de Suarez, who was bom in Valle de Juarez, a rich dairy-farming area on the borders of Michoacan and Jalisco. She has most generously spent countless hours traveling with me and teaching me about the very diverse regional cooking of Michoacan.

The word enjococadas means tortillas immersed in jocoque—jocoque can mean soured milk, cream, or yogurt in other areas, but here it refers to the cream skimmed off raw milk that has been left at room temperature overnight. It is collected over a period of several days and stored in an earthenware jug. It has a pleasant acidity, and although very thick, it is often whipped lightly before being used on uchepos (page 86) or corundas (page 70).

This is a very unusual and delicate-tasting dish depending totally on the quality of the tortillas —which should be freshly made and rather thin—and an excellent creme fraiche, which should be used instead of the jocoque. While the

CORN

cheese traditionally used is the salty, rather grainy anejo or cotija, I prefer to use a rather dry queso fresco.

Enjococadas are usually served as a “dry soup” or first course hy themselves, but they could well serve as a main dish—and a vegetarian one at that—with a lightly dressed salad.

Traditionally, enjococadas are assembled and then immediately reheated in a fireproof dish that is gently shaken over the flame. An oval copper gratin dish would be ideal for this, hut an alternative is to put them into an ovenproof dish and cover it loosely with foil so that the cream does not dry up.

1 am sorry, but there is nothing you can do in advance; this is last-minute, pan-to-mouth food.

V4 cup safflower oil, approximately

12 th in com tortillas (see note above)

2 cups creme fraiche

1V4 cups finely grated queso anejo or queso fresco (see note above)

3 A cup finely chopped w bite onion, approximately

Heat oven to 350° (if using alternative method).

Have ready a flameproof or ovenproof dish into which the rolled tortillas will just fit in one layer and a tray covered with two layers of paper toweling.

Heat enough of the oil to cover the bottom of a small frying pan and fry the tortillas one by one, adding more oil as necessary, until they are soft and well heated through but do not become crisp around the edge. Drain on paper toweling. Meanwhile, in another pan heat the cream until it bubbles and reduces for about 5 minutes. Immerse each tortilla in the hot cream, put about 1 tablespoon of the cheese and a little of the onion across the center of each tortilla, roll them up, and place side by side on the bottom of the dish. Pour over the remaining cream and the rest of the cheese and shake the pan over the heat until the enjococadas are well heated through and the cream is just bubbling (or heat in the oven for about 10 minutes). Serve immediately.

THE ART OF MEXICAN COOKING

ENJOCOCADAS II

(Casserole of Chicken Tacos and Green Sauce)

SERVES 6 TO 8 JIQUILPAN, MICHOACAN

This absolutely scrumptious recipe was prepared for me by the famous Mexican artist and craftsman Feliciano Bejar. It comes from his native Jiquilpan, in the northern part of Michoacan, which is a rich dairy-farming area.

It is really a rich casserole (although 1 hate that word as it has too many sloppy connotations in Mexican-American food) of layered tacos filled with chicken and chorizo/egg filling, with green sauce and cream. It is a meal in itself and is best served with a very lightly dressed salad. While all the component parts can be prepared ahead, the final assembling and baking of the dish have to be done at the last minute, or the tortillas will become soggy and disintegrate.

The size of the baking dish is important: it should be at least 2 inches deep and large enough to accommodate two layers of 10 small tacos —about 9 inches by 9 inches is ideal.

The layers of tacos should just be covered with, not drowned in, the sauce and generously but not too thickly topped with cream.

V 3 cup safflower oil, approximately, for frying

20 5-inch com tortillas

IV 2 cups thick creme fraiche

2 cups well-seasoned polio deshebrado para tacos (page 218), warmed through

2 cups chorizo/egg filling (page 320), warmed through

2 cups salsa verde (recipe follows), warmed through

Heat the oven to 375°. Have ready a tray covered with two layers of paper toweling.

Put a little of the oil into a small frying pan—it should be about Vs inch deep—and heat. When the oil is hot hut not smoking, immerse a tortilla until thoroughly warmed through and softened, about 10 seconds, but do not allow the edge to become crisp. Drain on paper toweling and repeat until all the tortillas have been fried.

Meanwhile, heat the cream and allow to bubble and reduce for about 5 minutes. Immerse one of the tortillas —the cream should lightly coat it. Fill with the chicken, roll, and set onto a warmed dish. The second tortilla may be filled with the chorizo tilling. Continue immersing in cream and filling a total of 10 tortillas —alternately with chicken and chorizo —to form the first layer. Spread with 1 cup salsa verde and a little of the remaining cream. Continue

CORN

with the second layer until all the tortillas have been used up. Top with the remaining sauce and creme fraiche and bake in the top part of the oven until bubbling, about 15 to 20 minutes. Serve immediately.

SALSA VERDE PARA ENJOCOCADAS II (Green Sauce for Enjococadas II)

MAKES 2 CUPS

This simple sauce can also be used for corundas (page 70).

1 pound tomate verde (about 22 medium)

3 (or to taste) chiles serranos, stems removed 1 garlic clove, peeled and rou gbly chopped 1 */2 tablespoons safflower oil sea salt to taste

Remove the papery husks from the green tomatoes and rinse briefly. Put into a saucepan, cover with water, and add the chiles. Bring the water to a simmer and cook for about 10 minutes. Remove the pan from the heat and let the tomatoes and chiles sit in the water for about 5 minutes longer.

Transfer the tomate verde and chiles with a slotted spoon to a blender jar, add the garlic, and blend until smooth (no extra water should be necessary).

Heat the oil in a frying pan, add the sauce, and cook over fairly high heat, stirring from time to time, until the sauce has reduced—about 3 to 4 minutes. Season with salt as necessary.

THE ART OF MEXICAN COOKING

TOSTADAS DE APATZINGAN

On a recent trip to the hot country of Michoacan I came across the perfect tostada. Apatzingan is a thriving agricultural center where a lot of street eating goes on, especially in the open-air Mercado de Aguates. It opens early in the morning and has a brisk trade with menudo and tamales, progressing through the day with pork stew served with morisqueta (boiled rice) and antojitos of various types (despite the great heat), ending with the evening pozole.

The crowd was thinning out as we arrived one evening to search out local food. We stopped at a tostaderia, specializing as its name implies in tostadas. They were not exceptional. We tried a bit of this and that but were still hungry when we returned to the hotel. In the dining room we saw people eating most impressive tostadas piled high with various layers, including one of very luscious-looking shredded pork.

The tostadas were made of very large com tortillas that had been fried crisp (you can toast them crisp in the oven to avoid so much grease; see page 16 ) and topped with the following layers:

a thin layer of frijoles rejritos (page 180) a thick layer of finely shredded lettuce

a thick 1 ayer of came de puerco cocida y deshebrado (page 248)

2 tomato slices

2 tablespoons sour cream or creme fraicbe some thinly sliced radishes

sliced white onions, wilted in lime juice as for cebollas encurtidas para tatemado

(page 364)

2 tablespoons Michoacan tomato sauce (page 340) a sprinkling of grated queso anejo or Romano cheese

And served on the side for those who like it more picante:

salsa de chile de arbol (page 344)

You will need both hands and a liberal supply of paper napkins.

CORN

FLAUTAS DE GUADALAJARA

Flautas (flutes) are the large crisp-fried tacos of Jalisco. The tortilla used is usually about 6 to 7 inches in diameter. When they are freshly cooked, the telita, or top layer that puffs up, is removed, leaving a very thin tortilla.

Various traditional fillings for flautas follow. A large spoonful is put along the center of the tortilla; then it is tightly rolled, secured with a toothpick, and fried in lard or oil until quite crisp and a deep golden color. After being drained on paper toweling they are served on a bed of shredded lettuce seasoned with lime juice, thin slices of radishes, about 2 tablespoons of salsa de plaza (page 348), and, if available, Tamazula sauce (see page 346), but it is not absolutely necessary.

This is pan-to-mouth food. Fbutas must he filled, fried, and eaten right away, or they become tough.

Fillings for Flautas

POLLO DESHEBRADO (SHREDDED CHICKEN)

MAKES ABOUT 114 CUPS TO FILL 6 FLAUTAS

2 tablespoons melted lard or safflower oil

3 tablespoons finely chopped whole onion

V 2 pound (about 1 large) tomato, unshinned, finely chopped 2 chiles serranos, cut into rounds 2 cups polio deshebrado para tacos (page 218) sea salt to taste

Heat the lard in a frying pan. Add the chopped onion, tomato, and fresh chiles and fry gently for about 5 minutes, stirring the mixture from time to time so that it does not stick to the pan. Add the shredded chicken and salt and continue cooking until the mixture is well seasoned and almost dry.

THE ART OF MEXICAN COOKING

RAJAS DE CHILE POBLANO (POBLANO CHILE STRIPS)

MAKES ABOUT 1 HEAPED CUP TO FILL 8 TO 10 FLA UTAS

3 tablespoons safflower oil 3 tablespoons finely chopped w bite onion 1 cup prepared rajas (see page 471) of chile poblano Vz pound (about 1 large) tomatoes, finely chopped, unpeeled sea salt to taste

8 heaped tablespoons crumbled queso fresco

Heat the oil in a frying pan, add the onion and chile strips, and fry gently until the onion is translucent. Add the tomatoes and salt and continue cooking until the sauce has reduced and is well seasoned—about 8 minutes.

Fill the flautas with the rajas, and before rolling add a good tablespoon of the cheese.

PAPAS GUIS AD AS (POTATOES WITH TOMATOES)

MAKES ABOUT 1 HEAPED CUP TO FILL 8 FLAUTAS

This sounds too simple for words, but it is delicious.

Vz pound (3 medium) cooked red bliss potatoes, unpeeled 3 tablespoons me ltedl ard or safflower oil 3 tablespoons finely chopped w bite onion

Vi pound (about 1 small) tomatoes, roughly chopped, unpeeled sea salt to taste

Mash the potatoes roughly with their skins—they should have some texture.

Heat the lard in a frying pan, add the onion, and fry gently until translucent, about 3 minutes. Add the tomato and cook over medium heat, stirring and scraping the bottom of the pan, for 3 minutes more. Add potatoes with salt to taste and cook until the mixture is almost dry and well seasoned.

CORN

PICADILLO BLANCO (GROUND MEAT)

MAKES ABOUT 2 CUPS TO FILL ABOUT 1 DOZEN FLAUTAS

V 2 pound ground beef, medium-fine grind with some fat 3 tablespoons finely chopped w hite onion

Vi pound (about 1 small) tomatoes, finely chopped, unpeeled V 4 cup roughly chopped Italian parsley sea salt to taste

Spread the meat over the bottom of an ungreased heavy frying pan and cook over low heat until the fat starts to exude; this will take about 10 minutes, and it will be necessary to stir the meat from time to time and scrape the bottom of the pan to prevent sticking. Add the chopped onion and cook for 3 minutes longer over medium heat. Add the tomato, parsley, and salt and cook until the mixture is fairly dry—about 8 minutes.

29

THE ART OF MEXICAN COOKING

TACOS DE REQUESON (Ricotta Tacos)

MAKES 6 TACOS

This is a most unusual recipe that was given to me by one of the old families of Patzcuaro. The contrast of textures and the taste of sharp sauce against the rather bland ricotta are surprising and quite delicious, the perfect vegetarian snack. They must be eaten right away, or they will become leathery.

THE SAUCE

J /3 cup fresh lime juice

sea salt to taste

Vs cup finely chopped radishes

1/4 cup finely chopped w hite onion

1 chile peron, hlack seeds removed and roughly chopped, or any hot green chile, chopped with seeds 1 tablespoon roughly chopped cilantro

THE TACOS

1 cup drained and lightly salted ricotta cheese 6 thin 5-inch com tortillas 6 toothpicks safflower oil for frying

Have ready a tray lined with a double thickness of paper toweling.

First make the sauce. Put the lime juice and salt into a glass bowl, mix in the rest of the ingredients, and leave for at least 30 minutes to marinate. This should make about 1 cup.

Spread 1 tablespoon of the ricotta over half of each tortilla. Fold over and secure with a toothpick.

Put oil to a depth of l A inch in a large frying pan and heat. When hot but not smoking, add a few of the tacos and fry, turning once until they are a golden color and quite crisp. Continue with the rest, adding oil if necessary.

Drain the tacos well on paper toweling and remove as soon as they are cool enough to handle. With a toothpick, ease them open and insert about 2 tablespoons of the sauce. Serve immediately; they cannot wait.

CORN

EFIGENIA'S CHILAQUILES

SERVES 4 MICHOACAN

Making a dish of chilaquiles is a simple and delicious way of using up stale tortillas, any leftover sauce, and some cheese. It is a national dish, and while ingredients and methods do vary from region to region, they do not vary that much. They are served mostly at brunch time, almuerzo, with eggs or grilled meat, accompanied by refried beans. This is Mexican soul food . . . and beware, it is addictive! This is how Efigenia, my housekeeper, prepares them, and while it is a very simple recipe, much will depend on the quality of the corn tortillas, the ripeness of the tomatoes, and the richness of the cream used.

34 pound (about 2 medium) tomatoes, broiled (see page 450)

2 chiles serranos, broiled (see page 472)

2 garlic cloves, peeled and roughly chopped sea salt to taste

V 3 cup safflower oil, approximately

6 large com tortillas cut into 1 V^-inch squares and dried overnight

V* cup finely chopped w bite onion

2 heaped tablespoons roughly chopped epazote

V 3 cup crumbled queso fresco

V 3 cup sour cream or creme fraiche (optional)

Have ready a tray lined with two layers of paper toweling.

Blend together the tomatoes (unskinned), fresh chiles, garlic, and salt to taste. Set aside.

Heat about half the oil in a frying pan and fry some of the tortilla pieces until slightly crisp and a pale gold color. Remove and drain. Fry the rest of the tortilla pieces, adding more oil as necessary.

Drain off all hut 2 tablespoons of the oil from the pan, return the fried tortilla pieces, add the sauce, and stir well over medium heat for about 2 minutes.

Sprinkle the onion and epazote over the top, cover, lower the heat, and cook, shaking the pan from time to time to prevent sticking, for about 8 minutes. By this time the onion should be transparent and the tortillas softened but not mushy. Sprinkle with the cheese and cream and serve immediately.

THE ART OF MEXICAN COOKING

CHILAQUILES DE TEQUILA

SERVES 4 TO 6

This recipe comes from an old Tequila family. Although now the chilaquiles are made with a tomato sauce, the daughters of the family tell me that they used to he made with the large, red, smooth-skinned chilacate used so much in Jalisco.

(I suggest using a dried Anaheim or New Mexican chile as a substitute.) Chilaquiles are generally eaten for brunch, often to accompany eggs or broiled meats.

6 large chilacates or a substitute (see note above)

2 cups water (to cover)

2 garlic cloves, peeled and rou gbly ch opped

V 2 teaspoon (or to taste) sea salt

V 3 cup melted lard or safflower oil, approximately

3 cups dried com tortilla squares or diamonds (about 15 small tortillas)

THE GARNISH

>A cup finely chopped w bite onion

V 3 cup finely crumbled queso adohera (in Jalisco), queso a tie jo, or Romano cheese

Remove stalks from the dried chiles, wipe with a damp cloth, slit open, and remove seeds and veins. Put the water into a saucepan, bring to a simmer, add the cleaned chiles, and simmer for 5 minutes. Put 1 Vi cups of the cooking water into a blender jar, add garlic, salt, and chiles, and blend as smoothly as possible. Pass the sauce through a fine sieve or strainer (the chile skins are very tough), pressing down well. Discard the chile debris and set the sauce aside.

Using a heavy 10-inch frying pan (ideally), heat about one third of the oil and fry one third of the dried tortilla pieces over medium to low heat until they are a light golden brown, remove with a slotted spoon, and drain on paper toweling. Add a little more oil and proceed with the rest of the tortilla pieces, one third at a time, adding more oil as necessary.

When you have finished frying, drain off all excess oil, return the tortilla pieces to the pan, add the sauce, and cook over fairly high heat until the sauce has reduced—about 8 minutes. Adjust seasoning, sprinkle the top with the onion and cheese, and serve immediately.

Note: The sauce should be of medium consistency, neither too dry nor too soupy. Add a little more water if necessary during the blending or cooking time to adjust.

CORN

TORTILLAS CON ASIENTO (A Oaxacan Tortilla Snack)

SERVES 1

Walking along the streets of Oaxaca any hour of the day or evening, you are likely to see women on the sidewalks selling what resemble turnovers made of large, soft tortillas. They are, in fact, the large, white, soft tortillas called blanditas doubled over and toasted in the pork drippings that seep through the dough.

As you bite into them they are textured and picante, rich and luscious all at once, the heartiest tortilla snacks that I know of.

Try to find really large (7- to 8-inch) com tortillas for this recipe, hut if they are not available, use the normal-sized ones, reducing the filling slightly so that it does not ooze out and scorch on the comal or griddle.

This snack lends itself to many innovations; they can be prepared ahead of time and taken on a picnic to he toasted on the barbecue grill or on a griddle over an open fire.

1 5V2- to 7-inch com tortilla

1 rounded tablespoon asiento (see Ingredients, page 275)

1 tablespoon frijoles fritos Oaxaquenos (see Filling, Tamales Je Frijol, page 75)

a thin layer of finely shredded cabbage

1 tablespoon crumbled queso fresco

1 V 2 teaspoons (or to taste) salsa Je chile pasilla Je Oaxaca (page 342) or other hot ch ile sauce

Spread the tortilla with the asiento and the rest of the ingredients in layers. Set on a hot comal or griddle for about 2 minutes, until it is well heated but not crisp. Double the tortilla over and press the edges together very firmly. Toast the tortilla for about 2 minutes on each side or until crisp and eat with your hands using a large paper napkin to protect your clothes.

THE ART OF MEXICAN COOKING

ENFRIJOLADAS (Tortillas in Bean Sauce)

SERVES 4 TO 6

A typical Oaxacan dish, enfrijoladas are served for almuerzo, the Mexican brunch, accompanied hy broiled or fried tasaja, air-dried beef, or as a main meal with polio con oregano (page 220).

If avocado leaves are not available, either fresh or dried, then add epazote — not a substitute but an acceptable alternative. While the bean sauce may be prepared ahead and stored or even frozen, the frying of the tortillas and the assembly of the dish should be done at the last minute before serving; preparing ahead and reheating will produce a sad, soggy mess.

THE BEAN SAUCE

2 tablespoons lard or safflower oil

V 2 medium white onion, thickly sliced

2 chiles de arhol, left whole, stems removed

a small hunch of tender avocado leaves or 5 large mature leaves or 4 hahy stems of epa 2 ote (see note above)

5 small garlic cloves, charred and peeled (see page 439)

V2 cup water

3 cups black frijoles de olla (page 179) wi th th eir broth sea salt to taste

THE REST

V 4 cup safflower oil, approximately 12 5V 2 to 6 -inch com tortillas 1 medium white onion, cut into fairly thick rings % cup crumbled queso fresco

rajas con limon (page 359) or chiles jalapefios en escaheche (page 356)

First make the sauce. Heat 1 tablespoon lard in a frying pan, add the Vi onion and dried chiles, and fry over medium heat until slightly golden. Transfer with a slotted spoon to a blender jar, reserving the lard. Hold the bunch of avocado leaves over an open flame or place on a hot comal and let them sizzle and singe slightly. Crumble the leaves, but not the thick stalks and veins, into the blender jar. Add the garlic and water and blend until smooth. Gradually add the beans and their broth and blend until smooth— you may have to do this in two batches, adding a little water to make the blades work efficiently.

Add a second tablespoon of lard to the pan and heat. Stir in the bean puree and cook over medium heat, stirring and scraping the bottom of the

CORN

pan from time to time to prevent sticking, until thickened and well seasoned— about 8 to 10 minutes. Adjust salt. Set aside and keep warm, covered, or the bean puree will form a crust on top.

Meanwhile, heat the l A cup oil in a small frying pan and fry the tortillas one at a time for a few seconds on each side until well heated through—they will probably puff up—but not crisp around the edge. Drain the tortillas on paper toweling.

Reheat the bean sauce, which may have thickened too much. Test by immersing a tortilla; the sauce should lightly cover it. If it is too thick, add about Vi cup hot water and stir until smooth. Bring to a simmer, immerse the tortillas one by one in the sauce, and fold into four. Sprinkle each serving with onion rings and cheese; serve the pickled chiles on the side.

THE ART OF MEXICAN COOKING

ENTOMATADAS (Tortillas in Tomato Sauce)

SERVES 4 TO 6

Entomatadas are a popular dish in Oaxaca for almuerzo, brunch, accompa-nied by some broiled air-dried beef, called tasajo. They are really simple enchiladas, but the tortillas are folded into four, and the tomato sauce has decided Oaxacan characteristics.

This dish lends itself to many interpretations for a light meal, accompanied by some broiled chicken or meat and a salad. It is best to use large com tortillas, if available, so that they can be folded more easily.

The sauce may he prepared ahead, but the frying of the tortillas and assembly of the entomatadas should be done at the last moment, or the dish will turn into a soggy mass of indistinguishable elements.

THE SAUCE

2 tablespoons safflower oil V 2 medium w bite onion, thickly sliced 4 small garlic cloves, peeled 2 whole allspice

2 chiles serranos (see page 4Yl) or chiles de agua (see page 463), broiled (optional)

V 2 cup cold water

1 V 2 pounds (about 3 large) tomatoes, broiled or stewed (see pages 450 an d 451)

3 small leafy stems of epa 2 ote sea salt to taste

THE REST