Suffragists staged a tableau at the US Treasury Department steps during their monumental parade in Washington, DC, in 1913.

Suffragists staged a tableau at the US Treasury Department steps during their monumental parade in Washington, DC, in 1913.

Library of Congress LC-USZ62-70382

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal…. ”

EARLY IN the new year of 1777, life was tense in revolutionary Baltimore, as it ‘ was across the 13 new states. The upstart Americans had launched a revolution against Great Britain and its monarch, King George III. The summer before, Baltimore’s citizens had swarmed the streets to hear words of a thrilling document just written in Philadelphia. It declared that “all men were created equal,” that they had “certain inalienable rights,” and that they were entitled to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

There was just one problem. This Declaration of Independence was handwritten on parchment with a quill pen and ink. Any printed copies were incomplete, because they didn’t show the signatures of those who had penned their names at the bottom of the page.

It was high time to put these radical words— along with the names of the brave men who had signed it—into the hands of people across the colonies. The document needed a publisher to print it in full.

Mary Katherine Goddard printed the first full copies of the Declaration of Independence.

Mary Katherine Goddard printed the first full copies of the Declaration of Independence.

Library of Congress bdsdcc 02101

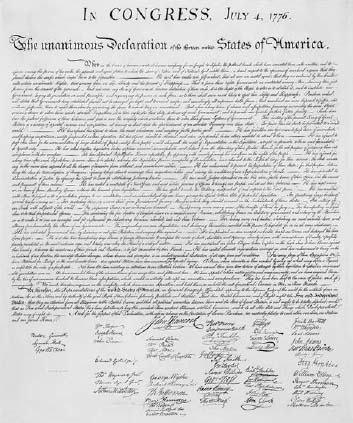

The Declaration of Independence.

The Declaration of Independence.

National Archives

That duty fell to a woman named Mary Katherine Goddard, editor of the Maryland Journal. She accomplished her task, and at the bottom of the broadsheet she added her name.

Goddard oversaw the task of printing the Declaration of Independence, but its words about liberty and freedom did not include her. In revolutionary America, women did not live as equals with men. Not one man who signed the Declaration even dreamed that women should vote, sit on a jury, or serve in government.

Most people in the Americas and Europe believed that women needed little education beyond being able to read, write, and do simple math. Women’s minds, people said, were far too weak to develop great thoughts or hold much knowledge. After all, didn’t the Bible say that women were the weaker sex?

From then on, America’s women fought a revolution of their own as they challenged the roles that men had written for them. Their battles were many.

Winning the right to vote was one struggle. It took 144 years from the signing of the Declaration of Independence until American women achieved suffrage—the right to go to the polls on Election Day and cast their ballots.

Early suffragists were women who desperately wanted an education and the opportunity to expand their minds. But first they had to overcome their fathers’ objections to schooling girls. This story about women’s suffrage opens with two of them, Lucy Stone and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. A third, Susan B. Anthony, got the education she wanted, but then she was forbidden to speak out in public against the evils of slavery.

The word “suffrage” might be new to you. It means “the act of voting in an election.” “Franchise” is another word for vote. A person who is allowed to vote is said to be “enfranchised.”

The terms “woman suffrage” or “women’s suffrage” that you read here refer to the unique topic of a woman’s right to vote. That right was not included in the original US Constitution. Each state was allowed to write its own laws about suffrage. In the early days of the United States, voting rights were usually reserved for white men who owned property. By the time the Civil War started in 1861, most states had granted suffrage to all adult white men.

It was time to act. Stone, Stanton, and Anthony gathered up their skirts and their courage and set out to find their voices. Though their paths diverged over the years, all three knew in their souls that American women must win what was rightfully theirs: the right to vote. Only then could they take a full role as citizens of the United States of America.