Lucy Stone and her daughter, Alice Stone Blackwell.

Lucy Stone and her daughter, Alice Stone Blackwell.

Library of Congress LC-USZ62-135241

ON A FARM near West Brookfield, Massachusetts, lived a young girl named Lucy Stone, the eighth of nine children. In 1820s Massachusetts, farm life was hard. Lucy and her sisters and brothers labored along with their parents; they cared for livestock and grew food. Like so many American women in the early 1800s, Lucy’s mother, Hannah, saw four of her nine children die.

For Hannah and other women who worked on farms, life could be bleak and cheerless. The work seemed to never end. They nursed their babies, kept their little ones from falling into fireplaces or down wells, cooked meals over open fires, cleaned, raised chickens, grew vegetables, and did the family’s washing and ironing—which itself took two days each week.

As a farm woman, Hannah Stone lived a rigid life with her duties spelled out for her. No one questioned how hard she worked; it was expected. The night before Lucy was born, her father was away from home, and Hannah had milked all the cows. When baby Lucy arrived, Hannah despaired. “A woman’s lot [life] is so hard,” she often said to her daughters. Lucy Stone grew up hearing that she should have been a boy.

Hannah’s husband, Francis Stone, worked hard on the farm as well, but Lucy feared her harsh, unbending father. Francis Stone was a drunk who slapped his children around. “There was only one will in my family and it was my father’s,” Lucy wrote.

Francis Stone tried to make a better life as he moved up from pounding cowhides in a tannery to running a 145-acre farm. Like other Americans, he had hopes that his sons would do better than he had. The farmer toiled to ensure that his sons went away to school in Maine, and he paid their tuition at Amherst College. But Francis Stone did not have the same goals in mind for his daughters. In Lucy’s day, few fathers did.

A young Lucy Stone. Library of Congress LC-USZ6-2055

A young Lucy Stone. Library of Congress LC-USZ6-2055

LUCY, LIKE her brothers, grew up learning how to read and do math, but she was not treated in the same way. In the 1820s, most “book learning” for girls took place at home, crammed in with all the other duties of each day. Only a few towns in Massachusetts had established public schools, so boys like Lucy’s brothers went to private schools in towns or left home to attend private academies. From there, the most promising—and those whose fathers would pay—studied at college to become doctors, lawyers, or ministers.

On Sundays, Lucy and her family sat in hard pews in the Congregational church in West Brookfield, listening to long-winded sermons. These were the days of America’s “Great Awakening,” when religious fervor swept across the young nation. From the shores of the Atlantic to the Mississippi River, crowds gathered to hear preachers urge them to save their souls. Thunderous ministers, the celebrities of their day, drew people from far and wide.

Children like Lucy heard American churchmen preach about personal salvation from church pulpits in cities and towns and wooden platforms erected in big tents at camp meetings. To get into heaven, roared the ministers, children and adults must accept Jesus Christ as their savior by welcoming him into their hearts. Thousands of people answered the call.

The converts, glowing with new faith, resolved to live as better people and to improve life for others. Their plans to reform American life led in two directions. The first was the temperance movement, whose members tried to ban people from drinking alcohol such as whiskey and rum. The other movement for reform was called “abolition.” Its goal was to abolish—put an end to—slavery in the United States.

EVEN as Americans moved from a nation of farmers to a land of city dwellers, housewives still made their own soap. Women saved grease left over from cooking meats like bacon by pouring it into a can. The grease had to be remelted over a fire before being processed into soap.

Like other women, suffragists had clothes to wash and dishes to clean. Lucy Stone’s recipes for hard and soft soap appeared in the Woman Suffrage Cook Book, published in 1890.

Try your hand at soap making. Fortunately, you won’t need clean grease or a can of potash. Potash, or “lye,” is a chemical compound made from ashes that can burn your skin.

You’ll Need

To start, place several cookie cutters on a baking sheet. Set aside.

Grate a bar of soap using the cheese grater. It’s easier to grate if you rest the grater on the cutting board. Pour the grated soap into the bowl.

Add 1 tablespoon of water and mix it into the soap flakes lightly with the spoon. For fragrance, start by adding ½ teaspoon of extract to the mixture. Smell it to see if the scent is strong enough for your taste. If not, add a little more extract until you like the scent.

Use the spoon to gather the mixture into a big ball. Now for some fun: use your hand to knead the mixture until the soap pieces stick together.

When the soap mixture has the consistency of thick dough, use your fingers to mold it into the cookie cutters. If you wish, heap the soap over the cutters, as shown.

Repeat the process until you have used up all of the mixture. Set the molded soap aside for three days to harden.

Push the soap out of the cookie cutters. Or leave it in and give your soap-and-cookie cutters to your friends as gifts.

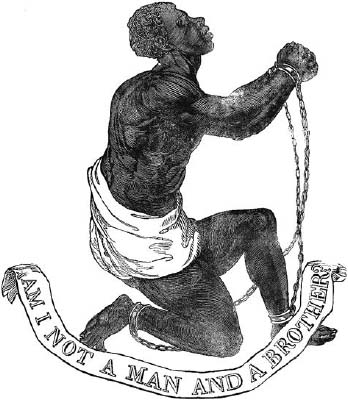

Abolitionists hoped to put a stop to slavery in the United States. This woodcut was created in 1837, when Lucy Stone attended antislavery lectures. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-44265

Abolitionists hoped to put a stop to slavery in the United States. This woodcut was created in 1837, when Lucy Stone attended antislavery lectures. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-44265

Lucy Stone was impressed by a strong-voiced abolitionist named William Lloyd Garrison. To most Americans, Garrison was a dangerous radical because he demanded an immediate end to slavery. Garrison published his views in his newspaper, The Liberator, which found its way into many homes.

Garrison was hated not just in the South but also in the North. As late at 1837, New Yorkers held slaves, so even some Northerners sympathized with Southern slaveholders.

Garrison and other abolitionists toured New England and the Mid-Atlantic states, speaking in churches and lecture halls to curious audiences. People like Lucy Stone looked forward to these meetings, a favorite way for folks to find entertainment during long winter nights.

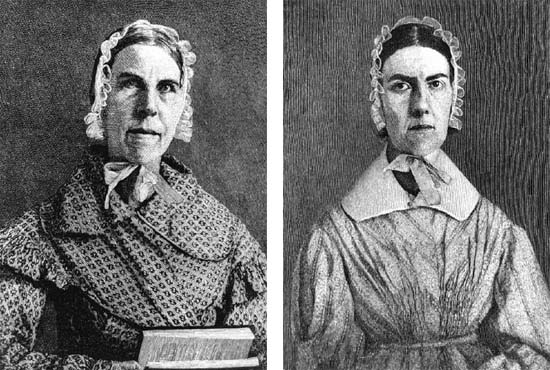

LECTURE GOERS were shocked when two sisters took the stage to speak to the mixed audiences of men and women. They were Angelina and Sarah Grimké, whose Southern father, a rich plantation owner and judge, owned slaves. The sisters hated the idea that anyone, including their father, could own other human beings.

First Sarah, and later Angelina, took the drastic step of leaving home and moving north to Philadelphia. There they became Quakers, who took a very open view of women’s rights. Like men, Quaker women were free to speak openly during their times of worship.

Angelina and Sarah learned to speak their minds. The Southern sisters then took things further and went on tour to speak about abolition in public meetings. At this point, even their fellow Quakers frowned when the Grimké women spoke in public.

Angelina Grimké asked for a chance to lecture about slavery in Congregational churches across New England, but church leaders— including Lucy’s—hated the idea. When the church in West Brookfield held a meeting to discuss Grimké’s request, Lucy Stone was there. Then Josiah Henshaw, a brave young deacon, allowed a woman to speak publicly about abolition. Furious, Lucy’s minister and others decided to act against him. The young man was tried in a religious court held in Lucy’s West Brookfield church.

Now in her late teens and teaching school, Lucy Stone attended the trial. A vote was called, and Lucy dared to raise her hand in favor of the open-minded Henshaw. She, too, shocked the people around her, and her minister scolded her in front of everyone.

Lucy wondered why the Bible said women should not speak in church. Perhaps, she thought, the Bible had been translated incorrectly from its earlier Greek and Latin versions. Lucy decided that she would learn both ancient languages and find out for herself.

More than anything, Lucy Stone wanted to go to college. In the 1840s, only one was open to women, and that was a frontier college, Oberlin, in far-off Ohio. Until the 1830s, not one college in the United States had admitted women—then Oberlin allowed them to walk through its doors. Lucy Stone’s father provided a perfect example of how difficult it was for young women to get a college education. Francis Stone refused to pay even one dollar of tuition, so Lucy decided to pay for it herself. Now called “Miss Stone,” she taught school for $16 a month (half of what a male teacher was paid), stitched shoes, and peddled berries and chestnuts in the farmers’ market.

The Quaker sisters Sarah and Angelina Grimké spoke openly against the evils of slavery.

The Quaker sisters Sarah and Angelina Grimké spoke openly against the evils of slavery.

Library of Congress LC-USZ61-1608, LC-USZ61-1609

Stone started saving for college when she was 16, and it took nine years before she had the $70 she needed to enter Oberlin in 1843. (Today, that $70 would equal about $1,600.) The journey to Ohio was a 500-mile adventure by railroad and then by ship across Lake Erie from Buffalo to Cleveland. To conserve her hard-earned cash, Stone did not pay for a bed. Instead, she slept atop her trunk on the ship’s deck under the stars.

At Oberlin, Stone continued to speak her mind. But even at open-minded Oberlin, she stood out from the other women students. Hats gave her headaches, so she wouldn’t wear them—which meant she had to sit in the back at church. She wanted to join her fellow students in debate—answer questions and make speeches in formal meetings—but women could not take part.

Moreover, Stone supported William Lloyd Garrison and hung a picture of him on her wall. Stone hated slavery, and she ached to speak in public to persuade others to become abolitionists. But as a woman, Stone could not speak in mixed company, only to groups of women like her. To Lucy Stone, this tradition was wrong.

When Stone was about to graduate from Oberlin, her sister wrote to her, saying, “Father says you better come home and get a schoolhouse.” But Stone had no plans to teach school. She had decided to step out from her traditional woman’s role and go on the road.

Lucy Stone had bigger plans: to earn her living on lecture tours by speaking out against slavery and for women. How, she asked herself, could she read about enslaved mothers and their daughters and not try to help them? If she didn’t speak out against slavery, then she was as guilty as anyone.

It wasn’t easy. Everywhere she went, Stone ran into roadblocks. The Anti-Slavery Society, her employer, wanted her to focus on abolition, so she made her antislavery speeches on weekends. During the week, when audiences were smaller, Stone felt free to talk about women’s rights.

She expected an assortment of boos and catcalls, but when Stone took the podium to speak, people pelted her with trash. Once she was hit in the head with a prayer book. Another time, angry men forced a window open during the cold of winter, pushed in a hose, and sprayed Stone with icy water. She wrapped a shawl around her shoulders and kept on speaking.

When onlookers set their eyes on Lucy, they saw a modest, quiet woman, now in her early 30s. She wore her hair in a plain, no-nonsense style that covered her ears. A newspaper described her looks and how she spoke: “Mrs. Stone is small, with dark-brown hair, gray eyes, fine teeth, florid [too red] complexion, and has a sparkling, intellectual face. Her voice is soft, clear, and musical; her manner in speaking is quiet, making but few gestures, and usually standing in one place.”

At times Stone felt alone, trying to convince others to share her ideas. Women, she declared, deserved better lives. In courts of justice and in politics, women deserved the same rights as men. At church and in matters of morality, women deserved equality and respect. At home, women should live as equals with their husbands.

Stone’s musical voice charmed her listeners. Stone also charmed a young man named Henry Blackwell. Stone was surprised at Henry’s attention. All her life, she had worked to get an education and then to become a lecturer. Lucy Stone did not envision herself as someone’s wife. She did not plan to marry anyone.

But Henry Blackwell had a different plan. When he met Stone, he fell madly in love. Henry admired strong women. Seven years younger than Stone, Henry came from a big family and had remarkable sisters. Every Blackwell sister followed her passion, and not one got married.

Two of Henry’s sisters, Elizabeth and Emily, became doctors. Others were poets, journalists, and authors. To the Blackwell girls, marriage meant giving up their independence, and they chose lives as single women. Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell spoke for them all when she declared that “true work is perfect freedom and full satisfaction.”

Stone took years before she agreed to marry Henry Blackwell. She kept putting off her answer until Blackwell proved himself to her. Finally, he did. In September 1854, Blackwell got word that a little girl, a slave, was traveling with her owners on a train through the Midwest. Blackwell jumped on the train in Salem, Ohio, scooped up the little girl, and took her away to freedom. Henry Blackwell had proved himself a fitting husband for Lucy Stone.

The following May, the wedding of Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell made headlines and shocked Americans. During their ceremony, Henry spoke about marriage and how it favored husbands over wives. Henry declared that, as Lucy’s husband, he would have no legal right to her earnings, her property, or her “person” (body).

Lucy dismayed her family and friends when she refused to take Henry’s last name and kept her own. Her decision was so outrageous that in later years other women who followed her example were called “Lucy Stoners.”

When Lucy and Henry’s daughter was born two years later, her name also reflected her parents’ progressive attitude. The happy parents named her Alice Stone Blackwell.

Henry Blackwell went on to become a businessman. He hoped to make enough money to retire and live a life of reading and following his interests, but he often failed at work. Meanwhile, Lucy Stone kept soldiering on, speaking out against slavery and for women’s rights.

Stone was single-minded in her devotion to her work. Fortunately, there were other women who felt like she did. In 1848, a group of them would find their voices and speak out.

MANY AMERICANS accepted the idea of educating girls—as long as they returned home after they finished college or became teachers. Teaching was considered appropriate for women; after all, women were in charge of keeping America’s children on the “straight and narrow” path to clean, moral living. Teachers were tasked with building strong character among their students.

Teachers did not need a college degree in order to work in a classroom. Only a few women went to Oberlin or the other women’s colleges that sprang up between 1830 and 1860. To be sure, most of those lucky college women had the backing of their parents, especially their fathers. In the 1800s, fathers ruled their wives and children. A father’s rule was law, and the laws of the United States agreed.

In early 1800s America, no women had the right to vote. Still, unmarried women had far more rights than married women had. Women without husbands could choose to work and spend their wages as they liked. They were free to buy and sell land, buildings, and other kinds of property, as well as to enter into business agreements by signing contracts. They could go to court and sue someone if that person damaged their property or hurt them. Likewise, if they damaged property, they could be sued.

But the moment a woman got married, all that changed. Under the law, a woman and everything she owned—from cows and barns to the combs in her hair and the shoes on her feet—became her husband’s property. Her money became his, and any pay that she earned now went to her husband.

These laws reached back far into history. Long before Great Britain founded colonies in North America, Englishmen lived under common law, a system that had been in place for hundreds of years. Now many states used common law as the model for their own rules about marriage.

American lawyers got their information about common law from thick leather volumes of Commentaries on the Laws of England. Written in the 1760s by William Blackstone, a British lawyer, the books explained England’s common law in clear terms that were easy to understand.

Although Blackstone wasn’t always accurate, many states in the United States followed his ideas about marriage. To Blackstone, a married couple was a single “being,” and the husband stood in charge of his wife. His words, written in England decades earlier, defined a married woman’s place in American society.

By marriage, the husband and wife are one person in law: that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage, or at least is incorporated and consolidated into that of the husband: under whose wing, protection, and cover, she performs everything.

Blackstone’s ideas were supported by another powerful influence—churches and synagogues. Protestant, Roman Catholic, and Jewish traditions declared that wives must obey their husbands. The Bible’s first creation story said that God made both Adam and Eve in God’s own image, but other Bible passages seemed to say that women were inferior creatures.

Ministers, priests, and rabbis based their beliefs on these Bible passages, the foundation for ancient Jewish laws governing marriage. Bible stories talked about the men who led the 12 Tribes of Israel and stood over their wives, children, and slaves. Women were actually given by their fathers to their husbands. In synagogues, men and older boys could speak during worship, but women and girls sat hidden behind a screen.

An engraving shows American reformers with three major documents: the Bible, the Constitution, and Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-90671

An engraving shows American reformers with three major documents: the Bible, the Constitution, and Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-90671

Sir William Blackstone. Library of Congress LC-DIG-pga-03621

Sir William Blackstone. Library of Congress LC-DIG-pga-03621

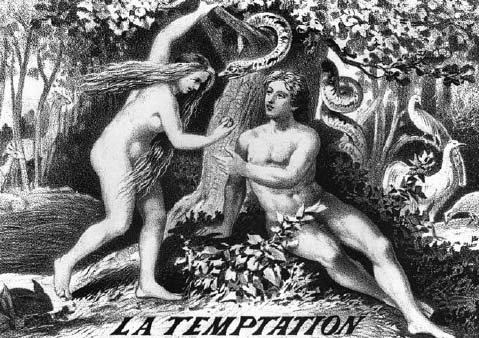

In Christian churches, there were similar ideas about the women’s roles. Few Christians questioned the established order of Creation described in the Bible’s second creation story. First came God, who gave the first man, Adam, dominion—or “authority”—over his wife, Eve. God also gave Adam dominion over their children and other living things. Then the Bible said that Eve became the first human to sin when she disobeyed God in the Garden of Eden. She ate a forbidden apple from the Tree of Knowledge, and she gave Adam a bite as well.

This engraving, printed on a tobacco label in 1869, pictured Eve tempting Adam. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-37639

From then on, churchmen claimed that all women were “daughters of Eve” who tempted hapless men into breaking God’s laws. Christians read from the Letter of Paul to the Ephesians, which said, “Wives, be subject to your husbands.” Except among Quakers, women could not serve as clergy or speak openly in church.

Plainly, it was a man’s world in 1800s America. Wives and daughters were ruled by husbands and fathers. Fathers decided how much schooling their daughters should have and whether it was worth paying for. Only a few young girls challenged their fathers’ rigid ideas about the roles of women. Two such girls, born three years apart in the 1810s, stood out from the rest. One was Lucy Stone. The other was Elizabeth Cady.