TO THE good fortune of women everywhere, Elizabeth Cady Stanton got the helping hands she needed. In the early 1850s she met a “stately Quaker girl” named Susan Brownell Anthony. Like Elizabeth, Susan had her roots in New York State and grew up in a big family. But Susan’s father, an open-minded Quaker, believed that women should speak their minds in public.

Daniel Anthony ran a textile mill in Battenville, New York, and owned other businesses. He encouraged Susan to develop her mind to become an independent thinker—and not to fear speaking out.

Susan’s father also believed in the virtue of hard work. When one of his factory workers was sick, Susan stepped in to work with the other mill girls. As a spooler in her father’s factory tending giant spools of cotton thread, Susan worked for two weeks and proudly claimed wages of her own.

As busy as Daniel Anthony was, he also carved out time to work as an abolitionist. Over time, he became more civic-minded and fell out of favor with his Quaker friends. Quakers preached against evil but did not believe they should take part in worldly activities like politics.

During one cold New York winter, a man in the Anthonys’ town froze to death. Near his corpse was found an empty whiskey jug, sure evidence of the evil of hard drink. Daniel Anthony was revolted, and he swore never to sell hard liquor in any of his businesses. He joined the crusade for temperance, and when Susan first began her own work as a reformer, she began by taking part in the fight against alcoholic drinks.

SUSAN ANTHONY adored her father and tried to follow his example as she grew up. She learned that complaining about evil was not enough. When she believed that society was wrong, she decided that she must act.

Daniel Anthony proudly sent his daughters to a Quaker boarding school near Philadelphia and traveled there with Susan to enroll her. Her older sister, Guelma, had prospered there, and Daniel Anthony had the same hopes for Susan.

However, despite her joy in studying mathematics and science, Susan had a dreadful experience at the school. The headmistress, a strict Quaker, seemed to single out Susan with biting words. Susan’s teacher taunted her in class, mocking her when Susan admitted she did not know the rule for “dotting an i.”

This teacher embodied the religious education of her own colonial girlhood, when adults believed that children were born wicked and must have their pride driven out of them. Like Lucy Stone and Elizabeth Cady, Susan was a serious girl who worried about her soul and her relationship with God. Over the months, the teacher drove so much poison into Susan’s mind that the girl began to doubt herself.

“Perhaps the reason I can not see my own defects is because my heart is hardened,” she confessed in her diary. “We were cautioned by our dear Teacher today to beware of self-esteem,” she added. Instead of building confidence in her sensitive student, Susan’s teacher left marks that wounded Susan and kept her from doing her best for many years.

Susan came home from school to find her father’s business in ruins. A nationwide financial panic in 1837—when scores of banks and businesses failed and closed their doors— led to an economic depression in 1838. The Anthonys lost the mill, their home, and most of their possessions. Daniel Anthony moved his family to Hardscrabble, New York, a village as bleak as its name.

Susan Anthony needed a job. In May 1839, she struck out on her own to teach briefly in a Quaker school. Over the next few years, “Miss Anthony” taught school. Often she took jobs in schools whose unruly boys had run off their male teachers.

Anthony had a close friend in Aaron McLean, the grandson of her father’s business partner. Then, in 1838, Aaron began to court her older sister, Guelma—he had eyes only for her. Anthony never mentioned her feelings in her diary, but she must have felt some regret that she did not make her romantic feelings for him known. Once Aaron married Guelma, Anthony could not share the same easy friendship with him.

To be sure, Anthony was courted by a number of eligible young men and received several proposals of marriage. But Susan B. Anthony was never to meet a man who excited her more than living the life of a single woman out to reform America.

When Anthony was 26, she became a headmistress herself. She moved to Canajoharie, New York, to teach school and began to explore a freer life away from the strict Quaker eyes that always judged her. She wore bright dresses and went dancing, but she took care to balance her life with reform work. She joined the Daughters of Temperance, an antidrinking group. Anthony also planned to work for abolition, but the townspeople in Canajoharie had no use for the antislavery cause.

When her father decided to start an insurance business, Anthony left teaching and came home to run the family farm. Her family was as active as always in New York’s reform efforts. On Sunday afternoons, abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison and a thundering man named Wendell Phillips came calling in the Anthonys’ parlor.

Their zeal to end slavery excited Anthony, and she joined the struggle. “What is American slavery?” she asked. “It is the legalized, systematic robbery of the bodies and souls of nearly four millions of men, women, and children. It is the legalized traffic in God’s image.”

In her diary, she left quiet evidence about taking a stand against slavery. On a summer day in 1861, she “superintended the plowing of the orchard…. The last load of hay is in the barn; all in capital order. Fitted out a fugitive slave for Canada with the help of Harriet Tubman.”

The Harriet Tubman whom Anthony mentioned in her diary was none other than the nation’s most famous “conductor” on the Underground Railroad. For escaping slaves, reaching Canada meant freedom.

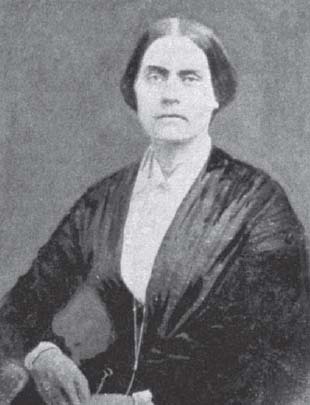

Susan B. Anthony at 26, sitting for her portrait. The Collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County

Susan B. Anthony at 26, sitting for her portrait. The Collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County

Susan B. Anthony was in her mid-40s when this portrait was made. The Collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County

Susan B. Anthony was in her mid-40s when this portrait was made. The Collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County

THESE WERE dangerous days for reformers. Across the United States, slavery was the hot topic in political meetings, church gatherings, and family dinners. Arguments were bitter. Many Americans, even those living in the North, had no problems with slavery and despised abolitionists.

In the North, black Americans, though free under the law, lived second-class lives. They were forbidden to enter libraries, theaters, lectures, hotels, trains, and horse-pulled buses. They were not welcome in most white churches or schools. Many white people feared the idea of emancipation—that slavery would end and black slaves would become free men and women.

Angry mobs could turn up at any point to disrupt a quiet meeting where abolitionists spoke out against the evil of slavery. More than once, Susan B. Anthony faced angry attacks. At one point, a group of men waving pistols and throwing rotten eggs chased Anthony and Samuel May, another abolitionist, off their speaking platform and out into the street. They escaped to a friendly home, but the mob built straw models of Anthony and May and burned them in effigy.

But even as Anthony risked her safety to fight slavery, she found that she could not speak out at all. The “mob,” as she called these unruly groups, hated the idea of women speaking in public. She was even more upset when most gentlemen of the educated class agreed with the mob. All too often, when she rose to speak at meetings, the men in charge told her to sit down. Their job was to speak; hers was to sit quietly and learn.

The ongoing fight just to speak in public fueled a fire in Anthony’s soul and sparked an idea. In order to make an impact on society, she decided to change society by bringing some measure of fairness into women’s lives. Such fairness, she believed, would come if American women could take part in the nation’s political arena.

From then on, Susan B. Anthony fought for one reform only: women’s suffrage, the right for America’s women to vote.

She had found her voice.

Lucy STONE’S gritty life as a farm girl contrasted sharply with the lives of girls like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. Stone watched her father and mother work side by side on the farm along with the rest of their family. However, Stanton’s and Anthony’s fathers worked in offices, a new trend in American life.

BEFORE natural gas was piped into homes for nighttime lighting, people depended on oil lamps to read, write, or do handwork at night. When Susan Anthony was a girl, she probably read by a lamp whose fuel came from oil extracted from whale blubber.

Make your own little lamp shine using just a few items. You will need an adult to help out as you create your lamp and light it.

You’ll Need

To begin, wash and dry a glass jar. Set aside. Measure the wick to the height of the jar plus one inch and cut with scissors. Place the wick in the small bowl. Pour olive oil over the wick until it’s just covered. Allow the oil to soak through the wick for 15 minutes.

To make a hole for the wick, turn the jar lid upside down on a wooden work surface. Use a hammer to drive a nail through the middle of the lid. Be sure the nail pierces the metal completely, but don’t hammer the lid to the work surface. Set aside.

When the oil has soaked through the wick, you are ready to assemble your lamp. Fill the jar half full of water. Now pour olive oil into the jar until it’s almost full.

Poke the wick through the jar lid from bottom to top. You want about ½ inch to peek out.

Tightly screw the lid to the jar so that the wick hangs into the olive oil.

Place your lamp on a nonflammable surface. Strike a match and light the wick. It might take a moment to set the wick on fire. (Hint: If your lamp burns only a short time, add more olive oil so that it comes nearly to the top of the jar and try again.)

In time, the wick will burn down, so you will need to use a straight pin to pull up more of the wick from below. But only pull the wick up through the jar top when it’s not burning.

Turn out the lights and see how well your lamp works. How well could you do homework with just your lamp for light?

Stanton and Anthony grew up as members of the middle class. As cities and towns grew in the 1820s and 1830s, middle-class men left home each morning to work somewhere else. Their jobs took them into the hard-hitting, rough-and-tumble environment of American commerce.

For middle- and upper-class American women and girls, life changed, too. Unlike their colonial foremothers, women lived their lives at home, separate from men, running households and raising children. It seemed that women lived in one world and men in another.

America’s opinion makers, including doctors, educators, ministers, and newspaper editors, admired this change in women’s roles. They prized the ideal woman as a mother and homemaker who lived in a “Cult of Domesticity.”

Outside the home, men did the “dirty work” of making money, practicing law or medicine, leading church congregations, or entering politics. Inside the home, women were supposed to make their dwellings calm, clean, and hallowed places.

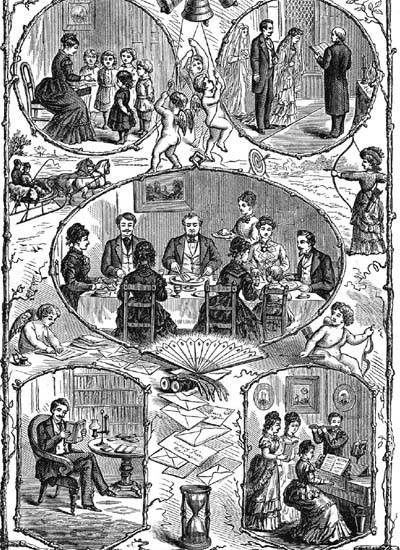

The Cult of Domesticity praised women’s roles as wives, mothers, and keepers of the home.

The Cult of Domesticity praised women’s roles as wives, mothers, and keepers of the home.

The Collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County

In the mid-1800s, one of America’s leading women was Sarah Josepha Hale, a magazine editor whose work reached homes coast-to-coast. Hale’s husband had died suddenly, leaving her with five children and no money. Hale needed a job, so she picked up her pen and started to write, first a book of poetry, then a novel.

Hale’s talent glowed. In a day when few women held powerful jobs, she won a position as editor of the American Ladies Magazine. Hale’s clever ideas and strong writing attracted readers. Her success caught the eye of Louis Godey, a publisher who recruited her to join Godey’s Lady’s Book. For 40 years, Hale edited America’s top women’s magazine.

Along with Godey’s famous fashion images, recipes, and housekeeping tips, readers enjoyed stories and poems by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Edgar Allan Poe. Hale also introduced her readers to Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose book about slavery took America by storm. Stowe, in fact, agreed with Hale on another matter: American women should be well educated and lead healthy lives.

Godey’s Lady’s Book was famed for its color illustrations of fashion for women and children. But Hale balked at the pulled-in corsets that gave women fashionable but unhealthy “wasp” waists. (Still, the wasp waist never went out of fashion.)

Hale pushed for her readers to exercise, ride horses, and even to swim, in case they were thrown overboard in a steamboat accident. She applauded modern household improvements—hand-cranked washing machines and rotary eggbeaters to replace the tiresome job of whipping cream with a fork.

Though Hale never asked women to step into the world of men, she prized the value of educating girls. She called for women to become doctors in female medical schools in order to solve another problem. When Hale was a young mother, too many women died in childbirth, too shy to seek help from doctors, who always were men.

Sarah Josepha Hale.

Sarah Josepha Hale.

In later life, Hale wrote to President Abraham Lincoln with a suggestion that the nation celebrate a new holiday: Thanksgiving. Most of all, Americans today know her as the author of “Mary Had a Little Lamb.”

IN the “olden days,” girls practiced standing up straight by walking with books balanced on their heads. Certainly that’s one way to learn how to stand tall, but today fitness experts agree that a daily dose of exercise is a better choice. In fact, 60 minutes—one hour— of activity every day is recommended for kids. (Are you a couch or computer potato? Do you really spend 60 whole minutes moving each day?)

The US government has a health-and-fitness website just for kids called BAM—Body and Mind. On this website you’ll find all sorts of ideas for ways to keep active for an hour each day—everything from ballet to basketball, from judo to ping-pong to yoga. Check it out at www.bam.gov.

Just for fun, try the old-fashioned way to practice good posture. It’s not as easy as you might think!

You’ll Need

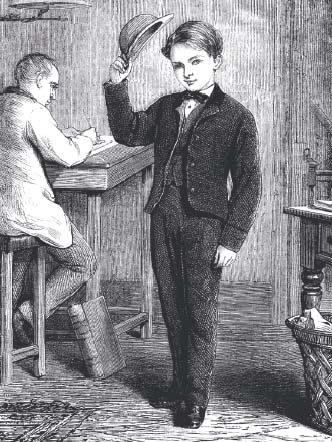

Read this recommendation of a teacher written in the 1850s. Put the book on your head, stand straight, drop your arms, and practice walking.

[G]reat advance in [exercise] might be made, if, whilst practising a slow marching walk with the foot lifted up and the step made from toe to heel, a heavy book, or other proportionate weight were carried on the head—the arms, in the meanwhile, hanging gracefully down. This should be practised till the weight can be carried for a considerable time without falling or moving—the spine in such case, in order to balance the weight, assuming a most erect and graceful posture.

Boys and girls were expected to stand up straight in Victorian times, when good posture was a sign of good background. iStockphoto, copyright © Linda Steward

Boys and girls were expected to stand up straight in Victorian times, when good posture was a sign of good background. iStockphoto, copyright © Linda Steward

This writer believed that young women who practiced their posture would surely be “modest in demeanour [behavior] and gentle in speech.” Do you agree ?

Do you think you could keep this posture every time you walk?

Women’s roles were strictly defined. They were charged with teaching their children about God and reading God’s word in the Bible. It was a mother’s duty to raise her sons to follow their fathers into the workplace. The same rules demanded that mothers teach their daughters the virtues of becoming loving wives and good mothers.

Not just men accepted this view of American life in the early and mid-1800s. Many— if not most—women agreed that they had no business going to college or working at jobs. Of course, working-class women had to work as servants or as mill girls in textile factories to manufacture cloth. But the middle class American woman, one whose husband could pay the bills, stayed inside her sphere an invisible glass ball. She became an ideal, a domestic goddess.

Even a women’s magazine—run by a woman—praised the homemaker as America’s model woman. Godey’s Lady’s Book and its strong-minded editor, Sarah Josepha Hale declared, “Our men are sufficiently money-making. Let us keep our women and children from contagion [sin and vice] as long as possible.”

Hale popularized the Cult of Domesticity as if it were a brand of soap or shampoo. From factory girls to rich women in their boudoirs, 150,000 American women read Godey’s Lady’s Book.

Women in the 1840s wore tight corsets to create wasp waists featured in Godey’s Lady’s Book.

Women in the 1840s wore tight corsets to create wasp waists featured in Godey’s Lady’s Book.