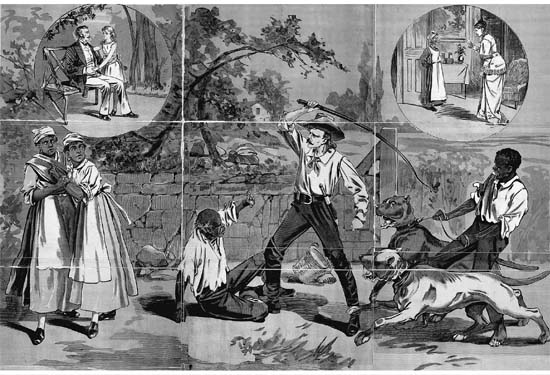

Scenes from Uncle Tom’s Cabin brought the issue of slavery to white Americans as nothing else had.

Scenes from Uncle Tom’s Cabin brought the issue of slavery to white Americans as nothing else had.

Library of Congress LC-USZ62-1351

AS A new decade opened in 1850, the movement for women’s rights pushed forward. Yet for the most part, Americans scoffed at the fledging efforts among women reformers. Meanwhile, abolitionists kept working toward an end to slavery, but the South rallied to protect its way of life. By the late 1850s, it seemed likely that the United States could split in two over the issue of slavery.

Sometimes reformers fought with each other to bring Americans’ attention to their efforts. Clearly, the antislavery movement and the women’s rights movement were rivals for people’s attention.

However, three women helped draw the public into both groups. These remarkable reformers were Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. Because they were not men, they stood out. Tubman, Truth, and Stowe gave American women a rightful place on the public stage.

HARRIET TUBMAN was born a slave but ended up not only escaping to freedom but leading more than 300 other slaves to free lives as well. Tubman started life on a Maryland plantation as Araminta Ross but changed her name to Harriet, her mother’s name. As a young girl in the 1820s, Harriet served as a house slave in her master’s home. But when she reached her teens, she was sent to do the backbreaking work of a field hand.

A feisty young woman, Harriet tried to protect a fellow slave from an angry overseer. The overseer threw a two-pound weight at the slave but missed and hit Harriet in the head. Ever after, from time to time she would pass out and experience blackouts.

In her teens Harriet was permitted to take a husband, a free black man named John Tubman. Then her master died, and Harriet Tubman faced being sold. Like all slaves who lived in Maryland and Virginia, Tubman dreaded being sold “down the river” to the Deep South, where slaves were often worked to death. Tubman trusted no one, not even her husband. Giving no inkling of her plans, Tubman slipped away from the plantation and followed the Underground Railroad north to safety. It was 1849.

As a former slave, Harriet Tubman did not know her birthday, but she stood for this portrait sometime between the ages of 40 and 55. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-7816

As a former slave, Harriet Tubman did not know her birthday, but she stood for this portrait sometime between the ages of 40 and 55. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-7816

Freedom was not enough for Tubman, however, and she became the Underground Railroad’s most-famed conductor. With her eyes on the North Star and a price on her head, Tubman made journey after journey back to the South to deliver more people to freedom, including her aged parents.

Abolitionists cheered Tubman’s accomplishments, as did Lucretia Mott, who understood that Harriet Tubman was a powerful symbol. Tubman was a woman doing the kind of hard work traditionally considered “man’s work.”

A GENERATION before Harriet Tubman was born a slave in Maryland, another girl was born a slave in the North. In 1797, little Isabella Baumfree, a black child, was the property of a Dutch American who lived in New York. As in the South, slaves in New York were bought and sold like horses or cows. When she was about 20 years old, her owner forced Isabella to marry another slave whom she didn’t love, and she gave birth to five children.

In 1827, the state of New York passed an antislavery law, and Isabella claimed her right to be free. Her master did not agree, so she left her home. Listening to the voices in her head that had spoken to her ever since she was a girl, Isabella became a preacher. She changed her name to Sojourner Truth. (To sojourn means “to stay someplace for a short time.”)

Sojourner Truth lived out her name in New England, where she traveled the roads to camp meetings and lectures. Truth stood out, not just because of her color and her gender. She stood nearly six feet tall in a day when few men topped out at more than five feet nine inches.

In 1851, Truth traveled from New England to east-central Ohio, where a women’s rights convention was planned at Akron. When she entered the first session in a church, she caused a stir. Not everyone welcomed a black woman walking into a church, recalled Frances Gage, an abolitionist.

The leaders of the movement trembled on seeing a tall, gaunt black woman in a gray dress and white turban, surmounted with an uncouth sunbonnet, march deliberately into the church, walk with the air of a queen up the aisle, and take her seat upon the pulpit steps. A buzz of disapprobation was heard all over the house, and there fell on the listening ear, “An abolition affair!” “Woman’s rights and n—s!” “I told you so!”

Fearful conventioneers came to Gage, worried that Truth might actually speak. The next morning, a series of ministers took their turns at the pulpit. Methodist, Baptist, Episcopalian, Presbyterian, and Universalist men declared their opposition to women’s rights. They offered the usual excuses.

One churchman preached that men were more intelligent than women. Another stated that woman came second to man because Jesus was male. Yet another minister added that because of Eve’s sin in the Garden of Eden, all women were equally sinful.

Once the ministers had finished their speeches, Frances Gage allowed Sojourner Truth to take the pulpit. Even the people staring through the windows could hear Truth’s ringing words. Gage recalled Truth’s speech:

“Well, children, where there is so much racket there must be something out of kilter. I think that ’twixt the negroes of the South and the women at the North, all talking about rights, the white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what’s all this here talking about?

“That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place!”

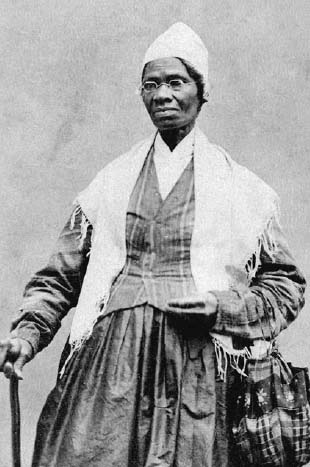

Wherever she went, Sojourner Truth wore a white cap. She did not know her age when she sat for this portrait in 1864. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-119343

Wherever she went, Sojourner Truth wore a white cap. She did not know her age when she sat for this portrait in 1864. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-119343

And raising herself to her full height, and her voice to a pitch like rolling thunder, [Truth] asked, “And ain’t I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! (and she bared her right arm to the shoulder, showing her tremendous muscular power) I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain’t I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man—when I could get it—and bear the lash as well! And ain’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain’t I a woman?”

Gage continued with Truth’s comments about women’s minds:

“Then they talk about this thing in the head; what’s this they call it? (“Intellect,” whispered some one near.) “That’s it, honey. What’s that got to do with women’s rights or negroes’ rights? If my cup won’t hold but a pint, and yours holds a quart, wouldn’t you be mean not to let me have my little half measure full?”

Gage wrote more about Sojourner Truth’s rebuke at the ministers.

And she [Truth] pointed her significant finger, and sent a keen glance at the minister who had made the argument. The cheering was long and loud.

“Then that little man in black there, he says women can’t have as much rights as men, ’cause Christ wasn’t a woman! Where did your Christ come from?”

Rolling thunder couldn’t have stilled that crowd, as did those deep, wonderful tones, as she stood there with outstretched arms and eyes of fire. Raising her voice still louder, she repeated,

“Where did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothing to do with Him.”…

Turning again to another objector, she took up the defense of Mother Eve, and she ended by asserting:

“If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down all alone, these women together ought to be able to turn it back, and get it right side up again! And now they is asking to do it, the men better let them.”

Long continued cheering greeted this. “Obliged to you for hearing me, and now old Sojourner ain’t got nothing more to say.”

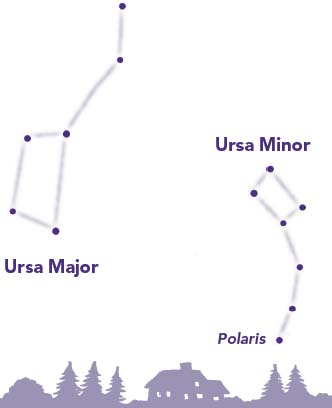

THE North Star is an unusual and helpful star. It certainly proved useful to Harriet Tubman as she led escaping slaves north to freedom.

Officially named “Polaris,” the star appears directly over the North Pole. Unlike all other stars that move in the night sky, Polaris seems to stand still. Since ancient times, sailors have looked to Polaris to help them calculate their latitude—how far north they are from the equator.

Several constellations appear to rotate around Polaris. Among these star groups are Ursa Major (known as the Great Bear) and Ursa Minor (known as the Small Bear). People usually call these constellations the Big Dipper and the Little Dipper. “Dipper” is a name for a long-handled drinking cup.

With one look skyward, Harriet Tubman could find the North Star and make sure that she was heading in the correct direction. But in a night sky filled with stars, the North Star isn’t especially bright. Tubman knew a trick for spotting it. First, she had to find the Big Dipper.

Right: The northern sky at night in July. Tubman used the Big Dipper, easy to find in the night sky, as a useful way to locate the North Star, which isn’t especially bright.

Right: The northern sky at night in July. Tubman used the Big Dipper, easy to find in the night sky, as a useful way to locate the North Star, which isn’t especially bright.

How did Tubman find Polaris? Discover for yourself.

You’ll Need

Head outside on a clear night and look skyward to find the Big Dipper in the north. Even if you live in a city with bright lights, you should be able to find the Big Dipper.

Do you see the “drinking cup”? Depending on the time of year, it might be on its side or upside down. Now find the two stars that make up the outside end of the cup, as shown:

Starting at the bottom of the cup, draw an imaginary line through both stars and continue your way onward. Your imaginary line will point to Polaris, the North Star. Can you see it?

Polaris is the last star on the handle of the Little Dipper. Now look for the Little Dipper. It faces the Big Dipper but is much fainter and can be hard to spot.

Bonus question: Why is the North Star named Polaris?

In one short speech, Sojourner Truth had summed up every good reason for women to stand forever equal with men.

IN 1851, a homemaker-author busied herself writing installments of an exciting novel about slavery in the American South. Harriet Beecher Stowe, a member of a prominent, outspoken family, had lived in Cincinnati, just across the Ohio River from the slave state of Kentucky. As a young wife and mother, Harriet saw slavery at work with her own eyes, and she met families who had escaped over the winter ice to freedom in Ohio. Stowe’s harrowing story drew her readers’ attention to the shattered lives of enslaved people.

In 1860, an Illinois woman was imprisoned for disagreeing with her husband. Elizabeth Packard, the wife of a minister with strict beliefs, challenged her husband’s preaching and left his church.

Her husband decided that if his wife disagreed with him, she must be insane. The laws in Illinois gave him power over her body and medical care, so Reverend Packard had her locked up in an “insane asylum,” a dreadful place that was meant to house people with mental illness. Mrs. Packard spent three years there until she was sent home, where her husband locked her in an upstairs room and boarded the window.

Friends managed to find Elizabeth Packard a lawyer, and they went to court. There, Reverend Packard used his narrow views about God to justify his treatment of his perfectly healthy wife. It took a jury— all members of which were men—only seven minutes to declare that Elizabeth Packard was not insane.

When Reverend Packard saw that he would lose the case, he took Elizabeth’s clothes and their children and left Illinois. It took another five years until Elizabeth Packard could see her children again. By then, they were mostly grown up.

Elizabeth Packard spent the rest of her long life fighting the Illinois law that her husband had used against her. She also won married women in Illinois the right to own property in their own names. Still, she didn’t paint herself as a suffragist. The clever Mrs. Packard disguised herself as an “anti” in order to win acceptance by male legislators who despised the idea of women voting.

Elizabeth Packard was imprisoned in a mental hospital because she disagreed with her husband.

Elizabeth Packard was imprisoned in a mental hospital because she disagreed with her husband.

From her desk in her family home in Maine, Stowe dispatched handwritten chapters of Uncle Tom’s Cabin to the National Era magazine. For a woman author to be so widely read was remarkable in American life. From the first page forward, readers were captured by her strong story that tugged at their hearts.

Stowe caught her readers’ attention in the first chapter. Two men, one a gentleman slaveholder named Shelby and the other a trader called Haley, discuss the sale of three slaves. First they talk about an elderly slave named Tom. Then they argue about two others: a little boy named Harry and his lovely mother, Eliza. The trader asks about Eliza:

“Come, how will you trade about the gal?— what shall I say for her—what’ll you take?”

“Mr. Haley, she is not to be sold,” said Shelby. “My wife would not part with her for her weight in gold.”

“Ay, ay! women always say such things, cause they ha’nt no sort of calculation [no sense about money]. Just show ’em how many watches, feathers, and trinkets, one’s weight in gold would buy, and that alters the case, I reckon.”

“I tell you, Haley, this must not be spoken of; I say no, and I mean no,” said Shelby, decidedly.

“Well, you’ll let me have the boy, though,” said the trader; “you must own I’ve come down pretty handsomely for him.”

In those few lines, Stowe set the scene for a classic tale. Published as a book in 1852, Uncle Tom’s Cabin sold an astounding 300,000 copies. Her scenes astounded Americans, too. In the North, Stowe became a heroine. In the South, it was a different story. Her book was banned, and Stowe’s name was poison. Stowe’s message against slavery enfuriated Southern men, who went on to question her womanliness because she wrote it.

Harriet Beecher Stowe became so well-known she was invited to the White House in 1862 to meet the tall and dignified president, Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln’s greeting to the petite author has become a legend. War between North and South had begun the year before, and when Lincoln took her hand, he said, “So you are the little lady who started the Civil War.”

This portrait of Harriet Beecher Stowe was taken in 1880, 30 years after her book took America by storm. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-11212

This portrait of Harriet Beecher Stowe was taken in 1880, 30 years after her book took America by storm. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-11212