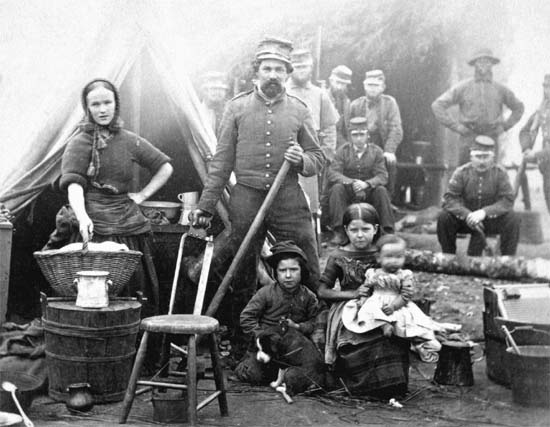

Sometimes families lived with soldier husbands and fathers in camps away from Civil War battlefields.

Sometimes families lived with soldier husbands and fathers in camps away from Civil War battlefields.

Library of Congress LC-USZC4-7983

THE CONTROVERSY over the right of Southerners to own slaves grew more heated as the United States moved toward war in the 1850s and early 1860s. Life in the North contrasted sharply with life in Southern society. The Northern states included growing cities, where people worked in factories, small towns, and thousands of small farms that were worked by their owners.

In the South, however, life was very different. Its economy depended on the success of giant tracts of farmland called plantations. White plantation owners depended on the labor of their slaves to grow their crops of cotton, tobacco, and sugar. Even small farms used slaves they owned or rented. A few large cities dotted the South, but they were not the same bustling centers of manufacturing and trade that were spreading from New England into the Midwest and down the Pacific coast.

As the young nation pushed west into the territories of Texas, Missouri, Kansas, and Nebraska, slavery became a hot issue. Americans added new stars to their flag and wondered: Would these states allow slavery or not? “Free soilers” called for new states to forbid slavery, a demand that made Southerners choke. The labor of slaves protected the South’s way of life.

When the Republican Party won the election of 1860 and Abraham Lincoln became president, people in the South roared ever louder. Lincoln was not an abolitionist, but the new president did not believe that slavery should spread farther in the West.

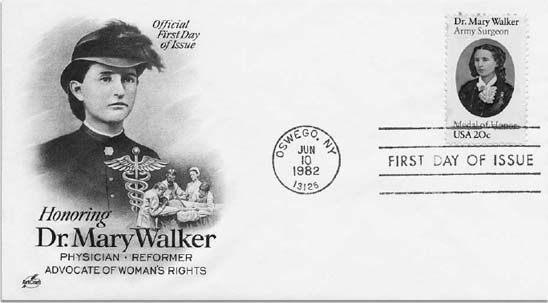

A “first day cover” of a postage stamp honored Mary Walker, a woman who cared for soldiers and was captured during the Civil War. United States Post Office

A “first day cover” of a postage stamp honored Mary Walker, a woman who cared for soldiers and was captured during the Civil War. United States Post Office

FROM VIRGINIA south to Florida and west to Texas, Southerners began to speak about forming a nation of their own. One by one, beginning with South Carolina in December 1860, Southern states seceded—withdrew— from the United States to form the Confederate States of America. By April the next spring, the two sides were at war. Northerners fought to preserve the Union, and Southerners fought to protect their right to live as a separate nation.

Over four bloody years, the two sides battled. With double the population and its factories and farms to supply its soldiers, the North held a huge advantage over the South. Even so, the war dragged on.

The cost in human lives shocked everyone. One out of two casualties ended in the death of a soldier. If a soldier were shot, luck was not on his side. More than likely, he would die from his wounds. Of the 1.5 million soldiers who fought for the North, nearly 360,000 died and 275,000 were injured. Among the South’s 800,000 soldiers, some 258,000 died and another 225,000 were wounded.

The hatred between North and South overshadowed every other issue, including the matter of equality for women. In both North and South, women of the upper and middle classes did what they could to support their fighting men. They held social events like teas and balls to raise money for their armies. They also knitted bandages and gloves, sewed blankets and uniforms, and marshaled collections of food to ship to the front.

As the war moved on, it became clear that families of ordinary soldiers who had been drafted into the army were suffering on the home front. It was up to the man of the house to send home his pay. Many soldiers didn’t, and their families went hungry. Again, women stepped up to help out these poor families with food to fill hungry children and clothing to keep them warm during long bitter winters.

In time, women went to war themselves, delivering vital supplies to field hospitals near the lines of battle. At first, they weren’t welcomed. Male doctors and surgeons doubted that ladies could withstand the blood and gore of these primitive hospitals, where the surgeon’s solution to a shattered leg was usually to amputate it.

However, a quiet teacher named Clara Barton changed their thinking. Barton, shy by nature but also caring, saw her wounded students returning from fighting for the Union and decided to deliver supplies right to the front lines. Once there, she stopped to care for wounded soldiers; she cleaned their wounds, changed their bandages, or just held their hands. Her valuable work soon changed the minds of army doctors, and they began to welcome women’s help as nurses. Years later, Clara Barton went on to found the International Red Cross.

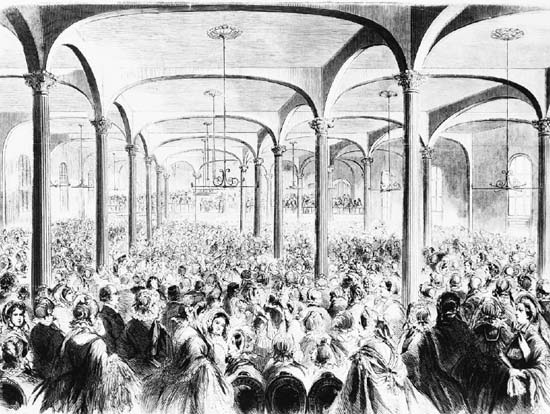

In 1861, “the ladies of New York” met in a big hall to organize a society to make clothes and lint bandages and to furnish nurses for the Northern army. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-132138

In 1861, “the ladies of New York” met in a big hall to organize a society to make clothes and lint bandages and to furnish nurses for the Northern army. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-132138

An old stamp honored Clara Barton, who pioneered women’s work as nurses during the Civil War. United States Post Office

An old stamp honored Clara Barton, who pioneered women’s work as nurses during the Civil War. United States Post Office

When the Founding Fathers wrote the Constitution, they planned it as a living document. They realized that, over time, the Constitution would require changes as American life moved on.

Article V of the Constitution describes the amendment process. Amendments can be introduced either in Congress or by a constitutional convention of 34 states. (Amendments are usually introduced by members of Congress.)

An amendment must be approved by a two-thirds majority vote in both the US Senate and the House of Representatives. Then the amendment is sent to the 50 states for approval in a process called ratification. Thirty-eight state legislatures are required to ratify an amendment.

The best-known amendments are the first 10, which we know as the Bill of Rights. Another well-known amendment, the 18th Amendment, banned the manufacture and drinking of alcoholic beverages in 1919. The 21st Amendment repealed that ban in 1933. In 1971, the 26th Amendment changed the national voting age from 21 to 18.

FOR THE time, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony set aside their drive for women’s suffrage to do war work for the Union. They joined hands with abolitionists who, despite the war, still had to press for President Lincoln to declare emancipation and end slavery once and for all.

In a campaign of their own, Stanton and Anthony formed the Women’s Loyal National League and organized a petition drive. Petitions were one of the few legal documents a woman could sign, and thousands penned their names to statements calling for the president to abolish slavery.

In the end, 300,000 women and men signed the petitions. The president signed the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, setting free the slaves in the Confederate South. (Slavery did not become illegal across the United States until the 13th Amendment abolished it after the Civil War.)

Stanton, Anthony, and their fellow suffragists had a vision. They felt certain that once the war was over and the country reunited, America’s leaders would recognize women’s war work and reward them with the right to vote.

In April 1865, the terrible war ended as the Confederate general Robert E. Lee surrendered his sword to the Union general Ulysses S. Grant. Now suffragists had something to look forward to. The US Constitution would need a new amendment, its 14th.

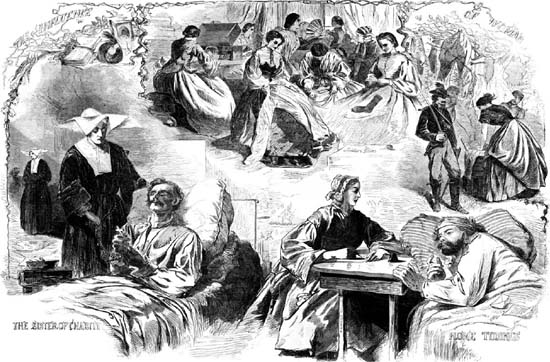

A national magazine showed women aiding Union soldiers during the Civil War.

A national magazine showed women aiding Union soldiers during the Civil War.

Library of Congress LC-USZ62-102383, LC-USZ62-102384

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. freed male slaves and to women both white Anthony expected that the 14th Amendment and black. Surely, they thought, bright days for would guarantee the right to vote to newly American women lay ahead.