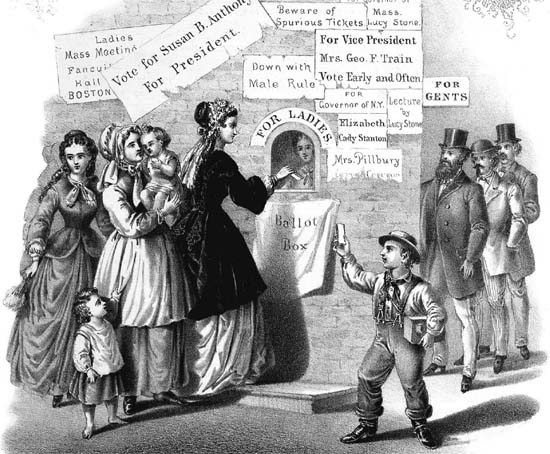

This drawing on a piece of music shows an artist’s take on the suffrage movement in 1869.

This drawing on a piece of music shows an artist’s take on the suffrage movement in 1869.

Library of Congress musmisc.awh0002

STANTON AND Anthony were wrong. Though the war was over and the slaves had been freed, abolitionists protested that two million free black men did not have the right to vote. Clearly, the US Constitution needed an update—a 14th Amendment. With that goal in mind, members of the Antislavery Society elected a new president, Wendell Phillips.

Phillips and Elizabeth Stanton were close friends, and he had always backed her quest for votes for women. Phillips wrote his first speech, in which he laid out his plans. Stanton expected that Phillips would include women, as well as freed slaves, in the new amendment.

But as Stanton listened to Phillips’s inaugural speech, she bristled. Wendell Phillips had changed his mind about the timing of women’s suffrage, and his words burned Stanton’s heart. “I say ‘One question at a time.’ This is the negro’s hour,” Phillips declared. Phillips and most of his friends felt that black men should have the vote immediately. Women could wait.

This engraving celebrated the new 15th Amendment, which granted suffrage to former male slaves. Neither black nor white women were given the right to vote. Library of Congress LC-DIG-pga-03453

This engraving celebrated the new 15th Amendment, which granted suffrage to former male slaves. Neither black nor white women were given the right to vote. Library of Congress LC-DIG-pga-03453

Radical Republicans in Congress, who favored rights for black men, also backed the 14th Amendment. It was a matter of politics, Republicans against Democrats. After the Civil War, the Republican Party held power in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. As former Confederate states wrote new constitutions and were admitted back into the Union, it was clear that they would be controlled by the Democratic Party.

In order to keep Democrats out of power, Republicans wrote the 14th Amendment with two million black men in mind: men who would be happy to support Republicans in the heavily Democratic South.

The opening lines of the 14th Amendment stated that former slaves were now American citizens:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.

As suffragists read the next section of the 14th Amendment, their alarm grew. For the first time ever, the word “male” appeared in the US Constitution.

It was plain to see that the Constitution, the nation’s most important document, made women second-class citizens. So, in 1866, Stanton and Anthony regrouped and founded the American Equal Rights Association. They invited former abolitionists to help fight for votes for women and newly freed slaves.

Congress passed the 14th Amendment in July 1868—a great victory—and the document went to the state legislatures to be ratified. Even so, the 14th Amendment did not guarantee black men a right to vote. Therefore, a group called the Radical Republicans proposed a 15th Amendment. This amendment said that states could not deny voting according to “race, color, or previous condition of servitude [slavery].” Nothing mentioned women and their voting rights.

Elizabeth Stanton and Susan Anthony were outraged. How could the Constitution give the vote to men, former slaves who could not read or write, when well educated, cultured women like themselves could not? From then on, Stanton and Anthony felt that the vote should be reserved for educated people.

Other news frustrated them. In New York, the state legislature had backtracked on the Married Woman’s Property Act. Once again, only fathers—not mothers—held legal guardianship of their children. It seemed to Anthony that the rush to give the vote to black men would overwhelm women’s chances to win votes of their own.

IN 1867 Stanton, Anthony, and Lucy Stone headed west to Kansas. There they joined Clarina I. H. Nichol, a Kansan well-known for her strong views on women’s rights. In the fall election, men across Kansas (all white, of course) would vote on the issue of suffrage for both blacks and women. The suffragists had work to do.

Many Kansans echoed the same views that held fast in the East. “It is time for the Negro to have the vote,” they heard. “If women get the vote, they’ll take away our taverns and our liquor,” was another complaint. Others griped about the “outsiders” who had come to Kansas to stir up trouble. Then, with just two months until Election Day, Elizabeth Stanton and Susan Anthony gained an unexpected backer—an unsavory man named George Francis Train.

The flamboyant Train wore lavender goatskin gloves and had his eye on one day becoming president. A self-made man, Train did business in real estate and railroads. Train had a mouth and a reputation as loud as his fancy clothes. In a time when people freely used hateful words to talk about black Americans, Train talked about people of color in the crudest possible terms.

George Francis Train pictured with his famous lavender gloves.

George Francis Train pictured with his famous lavender gloves.

Library of Congress LC-USZ62-127495

WHEN we look at a photo of Susan B. Anthony with her tight lips and black dresses, it’s hard to imagine her as a living woman with more energy than three people put together. As you view pictures from the 1800s, do you think of their subjects as “real” people?

Susan B. Anthony wore black, but her dresses were of fine quality and detail. Often she added a red shawl when it was chilly.

Susan B. Anthony wore black, but her dresses were of fine quality and detail. Often she added a red shawl when it was chilly.

Library of Congress LC-USZ62-23933

In Anthony’s time, camera film needed a fairly long exposure to light, sometimes as long as 10 or 15 seconds. If people moved, their image would blur. That’s why they didn’t smile in photos—or it might be they were hiding their bad teeth.

Can you imagine yourself as a Victorian girl or boy? Dress up and take your picture— Victorian-style! If you are lucky enough to have an older relative with a trunk full of vintage clothes, ask if you may use them. Otherwise, search through a thrift store to find pieces for your outfit.

You’ll Need

Let your imagination roam as you plan your outfit. Study the photos in this book for ideas. Think about how you will style your hair. Plan the setting for your photo. Will you stand or sit? Will anything else be in your picture? How will you hold your hands and arms?

Adjust the settings on your camera to take pictures in “sepia” tones. Sepia is the brown color you see in many old-fashioned photographs. Many digital cameras have settings to take pictures this way.

When it’s time for your “photo shoot,” ask your helper to take your picture using different poses. Remember: Don’t smile!

Download the pictures onto a computer and study the results. Which do you like best? If you weren’t able to set your camera to take the pictures in sepia colors, use a photo-editing program to make the adjustments on the computer.

Print out your favorite shots on the high-quality paper. Dab the corners with a bit of rubber cement and mount them on the construction paper. Look at your photos. Can you imagine yourself as a young person in the 1800s?

However, George Train believed that women should have the right to vote, so Elizabeth Stanton and Susan Anthony welcomed his help and his money. Even better, Train was a media whiz, and he had a suggestion. Why not start a newspaper to build support for suffrage? Anthony jumped at the idea, and the Revolution, the first suffragist newspaper, appeared with the tagline “Men their rights and nothing more; women their rights and nothing less.”

The Revolution was unlike any other women’s publication. Besides the usual articles on homemaking and child care, the Revolution gave readers news about real women doing active things in American life. Articles reported on women in all walks of life, from the very few professionals like doctors to factory women organizing labor unions in search of better pay and workplaces.

But then Anthony went too far. In the Revolution, she linked the American Equal Rights Association directly to George Train.

Lucy Stone was thunderstruck that Susan and Elizabeth would join forces with the likes of George Train. “I am utterly disgusted and vexed,” she wrote to a fellow suffragist. “[O]ur grand cause is dragged in [Train’s] bad name—all without my knowledge.”

Former abolitionists agreed. William Lloyd Garrison, long a friend to Stanton and Anthony, was “mortified and astonished beyond measure in seeing Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony travelling about the country with that harlequin [joker] and semi-lunatic George Francis Train.”

Most felt that Stanton and Anthony had put on blinders in the way wagon drivers blinkered their horses with eye flaps to keep them looking straight ahead. Anthony could not see why so many in her circle were upset. She fought back with stinging words that ripped old friendships apart. “I AM the Equal Rights Association. Not one of you amounts to shucks [a “hill of beans”] except for me.” She said to Lucy Stone, “I know what is the matter with you. It is envy, and spleen, and hate, because I have a paper [the Revolution] and you have not.”

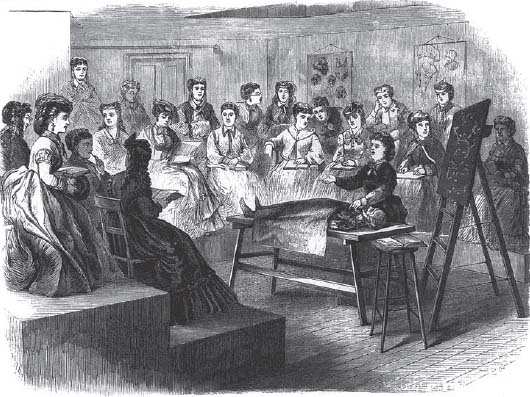

This 1870 illustration shows the unusual sight of women in anatomy class in an all-female medical school. Library of Congress USZ62-2053

This 1870 illustration shows the unusual sight of women in anatomy class in an all-female medical school. Library of Congress USZ62-2053

MANY plays about suffragists have appeared onstage. You and a few friends can produce a play of your own by staging a readers’ theater. The National Archives, which houses famous documents and records that make up US history, has a play on its website.

The play is titled Failure Is Impossible, named for Susan B. Anthony’s famous statement. It features a narrator and three readers who play the roles of 15 women and men who worked for suffrage. From Abigail Adams to Carrie Chapman Catt, the play gives an overview of the suffrage story.

You’ll Need

Download and print out four copies of the play. Read through it and assign parts to each reader. Each person should practice alone at first. When you are ready, practice reading the play from beginning to end.

Get ready for “opening night”! Gather an audience and perform Failure Is Impossible. Perhaps you can perform it for your class at school or in a community center.

These women, once so united in their work for women’s rights, fought like wolves. They held secret meetings, wrote hush-hush letters, and told tales behind each others’ backs. With their eyes fixed on the prize of winning women the vote, Anthony and Stanton dropped their old friendships and battled onward. It seemed they did not care how many friends they lost.

In the coming months, the movement for women’s suffrage split in two. Suffragists like Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell, former abolitionists, and other moderates backed the 15th Amendment. Let the black man vote, they felt. Surely votes for women would follow.

With this outlook, Stone, Blackwell, and another suffragist named Julia Ward Howe launched the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) in 1869. Stone moved from New York to Boston to live closer to other moderate suffragists.

Stone’s long, patient view of things underscored the American Woman Suffrage Association. The group planned its strategy: grassroots campaigns in every state. AWSA worked from the bottom up by recruiting women and men to push for suffrage where they lived. From there, citizen suffragists could point their efforts at their state legislators. With enough influence, states would have no choice but to give women the vote. State by state—this would be the AWSA’s way of doing things.

When Victoria Claflin Woodhull became the first woman to run for president of the United States in 1872, Stanton and Anthony applauded her bold vision. Dynamic yet offbeat, Woodhull held a broad, open view of what women’s lives could become. She wanted women to do everything that men did.

Born in 1838, Victoria Claflin grew up the daughter of spiritualists, a shady couple who said they were in touch with the dead. At 15, she married a Dr. Woodhull and had two children. But as her alcoholic husband came and went, Victoria decided to make a change.

Tiny, blond, and bright, Victoria Woodhull charmed her way into high society. She and her sister Tennessee started a women’s newspaper and became the first women to act as stockbrokers. Like their parents, the sisters held seances and claimed they could communicate between this world and the next.

Woodhull’s radical views upset the stodgy Victorians around her and overshadowed her successes. Among other extreme ideas, Woodhull believed that couples should be free to divorce, a notion that infuriated most people. In real life, she practiced what she preached, marrying a second husband before legally divorcing the first.

As Woodhull’s fame grew, her extreme opinions about women’s rights drew Elizabeth Stanton like a moth to a candle. Susan Anthony, however, held back. She feared that Woodhull was out for her own gain, out to “run our craft [boat] into her port and no other.”

Without asking Anthony, Stanton invited Victoria Woodhull to speak at a NWSA meeting. Anthony got angry and Stanton withdrew, leaving Anthony in charge. When Victoria Woodhull showed up to take the podium, Anthony sent her away. Woodhull appeared again the following night and started speaking. When she wouldn’t stop, Anthony turned out the lights.

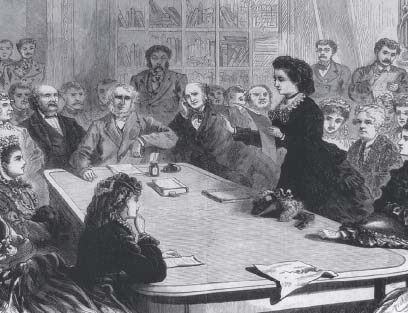

A woman thought to be Victoria Woodhull lobbied members of the House of Representatives to give women the vote.

A woman thought to be Victoria Woodhull lobbied members of the House of Representatives to give women the vote.

Library of Congress LC-USZ62-2023

Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton never agreed about Victoria Woodhull. Woodhull herself moved to England, where she took a third husband, lectured, wrote books, and gave her wealth away to good causes. She died in 1927.

To boost AWSA’s efforts, Stone launched her own newspaper, the Woman’s Journal, to compete with the Revolution. Like the Revolution, the Woman’s Journal covered topics that interested middle-class housewives in the 1870s. The Journal, however, took a much quieter tone that appealed to a wider group of women.

Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton formed their own National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) in New York City. They campaigned against the 15th Amendment and continued to press for a constitutional amendment to give American women the vote once and for all. Nothing less would ever satisfy them.

Eventually Anthony and Stanton dumped George Train and moved the publishing offices of the Revolution out of his building. Men were no longer allowed to join their group, in sharp contrast to Lucy Stone’s suffrage organization.

Despite all their hard work and good intentions, the Revolution folded in three years. Its extreme outlook did not appeal to most Americans. The newspaper could not keep enough readers and advertisers to run a profit. Susan B. Anthony had invested $10,000 of her own money—a giant sum—in her paper. Later she had to pay it back by lecturing and writing. In contrast to the Revolution, the Woman’s Journal, with its moderate views and popular tone, stayed in circulation until 1931, bringing its message to homes across America.

The split in the suffrage movement offered a lesson to anyone in the United States who was thinking about reform. There would be two sides, with different ideas, about how to right something that was wrong. One side— Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and NWSA—was far ahead of its time. On the other side were moderates like Lucy Stone and AWSA, who stood for the larger—and quieter—group of reformers whose views on suffrage were acceptable to more Americans. Numbers proved their case; AWSA always counted on far more members and a larger treasury than NWSA.

AWSA and NWSA stayed divided for 20 years.

THESE WERE the days of Victorian America, when society followed a set of rules named for Britain’s prim, upstanding Queen Victoria. Women were expected to dress modestly and follow strict standards of behavior. Unpleasant topics were not to be discussed openly.

THE Woman Suffrage Cook Book offers many cake recipes like this one. The cookbook’s editor took for granted that her readers knew how to bake cakes. (Today’s cooks—not so sure!) Girls had to learn the steps, and there were books to teach them. One was Six Little Cooks: or, Aunt Jane’s Cooking Class, a girls’ book published in 1877. Read and see how times have changed:

Accordingly the class was called together for a general examination and review…. Then Aunt Jane began…

“What is the first thing you must provide yourselves with when you are going to cook?”

“Clean hands and nails and tidy hair.”

“Next?”

“Clean aprons.”

“What must you have in the kitchen?”

“A good fire and plenty of hot water.”

“What is the rule about dishes and other utensils?”

“To use just as few as we possibly can, and manage so as to take the same one for several things when it won’t spoil the taste of what we’re making.”

“What ought you to do with flour?”

“Sift it, always.”

“What must you do in breaking eggs?”

“Break each one into a separate saucer before you put it with the rest.”

“And if you accidentally get one in that isn’t fresh?”

“Throw away the whole dishful!” “How about separating the yolks and whites?”

“Break them separate for all kinds of delicate cake, or for anything that is to be very light. But the recipes generally give you directions.”

“Is there anything where it is best not to separate them?”

“Baked custards, and gingerbread, and such things.”

“Rather indefinite, but no matter. When must you use ‘cooking butter’?”

“Never!”

“And skim-milk?”

“Never when you can get any other.”

“In making cake, what do you do first?”

“Rub the butter to a cream, and then put the sugar with it, and then the yolks of the eggs (after you have beaten them).”

“How do you generally put in white of egg?”

“Alternately with the flour, unless you have different directions.”

“And soda?”

“The last thing, except flour, and then you must bake anything immediately and not let it stand.”

“How do you prepare the soda?”

“Dissolve it in something—warm water, or sometimes, vinegar.”

“And cream tartar or baking-powder?”

“Sift it with the flour.”

Wow! Today’s mixes make cake baking much easier and taste just as good. However, homemade frosting still beats anything you find in a can. Several recipes for chocolate frosting appear in the Woman Suffrage Cook Book. Bake a cake, ice it with frosting you make yourself, and see if you agree.

You’ll Need

For the cake:

For the icing:

Bake the cake in the baking pan by following the directions on the box. When the cake comes out of the oven, allow it to cool for several hours in the pan on a cooling rack.

To make the icing, grate the chocolate into the small bowl. Then bring the ¼ cup of water to boil in the saucepan. Turn down the heat to very low. Using the wooden spoon, mix the sugar and grated chocolate into the water until they dissolve.

Keep cooking the icing at very low heat for 10 minutes. The icing will bubble up from the center. Stir it often to keep it from burning. Using a spatula, spread the icing over the top and sides of the cooled cake. Then cut the cake into serving-size pieces.

As Victorian women, Lucy Stone and others kept quiet in public about touchy issues that affected women and girls. Like so many wives, Stone understood heartbreak when Henry Blackwell strayed from their marriage and saw another woman. Stone decided not to leave her marriage, keeping to Victorian ways and her growing belief that divorce was wrong. (In time, Blackwell returned.)

But to Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, hushing up problems in the Victorian way was no solution at all. They talked— loudly—about all sorts of issues, topics such as wife beating, divorce, and the right of women to use birth control to manage the number of children they bore.

Such concerns were not considered proper talk in public. Victorians did not discuss diseases such as cancer or mental illness. It was unthinkable for a middle- or upper-class woman to appear in public when she was pregnant.

Young women often entered marriage not understanding “where babies came from.” Though families had fewer children than earlier in the century, large families were still expected and respected. All the same, as in the early 1800s, the grim truth was that women Western homesteads. In cemeteries, it was com-often died giving birth. Many women worked mon to see a headstone for one man flanked by themselves into early deaths on lonely farms or the graves of two or even three wives.

Two thousand miles from and 21 years after the first Woman’s Rights Convention at Seneca Falls, the state of Wyoming granted suffrage to women. Ever since, Wyoming’s nickname, the “Equality State,” has stuck.

When Wyoming’s governor signed the law in 1869, a Wyoming woman named Esther Morris cheered. Morris had started her working life as a seamstress and bonnet maker in New York, but when she married a man with three sons, they moved west during a gold rush.

The following year, Morris was appointed justice of the peace in South Pass, which made her the first woman in the United States to serve in public office. Six feet tall and strong featured, Morris heard cases as she sat on a bench in her log cabin. Her grown sons served as court clerks. Her first order was for everyone to keep their shooting irons outside.

Historians disagree whether Morris worked for suffrage, but there is no doubt that she held court in Wyoming. She heard criminal cases (most involving men who were charged with assault) and civic cases (such as when people fell into debt). As a judge, she also married people, including a scandalous couple who had lived together for two years “without benefit of clergy or the law.”

Esther Morris wanted to run in the next election to keep her job. But neither political party would nominate her, and she stepped down. She was proud to have passed the test of a woman’s ability to hold public office. The same year she ran her courtroom, Wyoming had its first all-woman jury.

When Wyoming became a state in 1890, women’s suffrage became part of its constitution. Morris died in 1902, privileged to vote in Wyoming’s elections but not for president of the United States.

Wyoming also boasted the nation’s first woman governor, Nellie Tayloe Ross. Ross became the state’s top official in 1924. Her husband the governor had died in office, and Ross won a special election to succeed him. Then Ross went on to a national job. In 1930, she became the first woman to serve as director of the US Mint.

Wyoming’s women won the vote in 1912.

Wyoming’s women won the vote in 1912.

Library of Congress LC-USZ6-2166

WOMEN WHO lived far from the big cities of the East offered a flicker of hope to Susan and Elizabeth in 1869. Men in Wyoming’s legislature voted for women’s suffrage. Though Wyoming was still a territory and not yet a state, suffragists now had a triumph on which to hang their bonnets.

Two months later, the Utah Territory legislature also enfranchised women, much to the surprise of outsiders. Utah was settled largely by Mormons, known formally as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Mormons practiced polygamy, allowing one man to have several wives. Polygamy offended most Americans. Antisuffragists accused Utah’s men of trying to build political power by giving their women the vote.

In general, Westerners took a broader view of women’s rights than Easterners did. As in colonial times, Western women worked side by side with their husbands on ranches and farms. Little by little, women were permitted to elect school board members and, later, to vote in local elections.

But, as in the East, suffragists ran into roadblocks. In 1877, a hot campaign for women’s suffrage in Colorado brought scorn from a Roman Catholic bishop. A Protestant minister preached that suffragists were “bawling, ranting women, bristling for their rights.” Though Elizabeth Stanton and Susan Anthony boarded trains and headed west to speak to Coloradans, their efforts failed.

Over the next 13 years, the suffrage movement in Colorado regrouped. Scores of women organized local efforts by making their case through newspapers and political groups. They changed men’s minds, one at a time. Time helped, as the Populist political party built support in the West. Made up of farm men—and their wives—Populists believed in votes for women.

Colorado’s busy suffragists also had the leadership of a young up-and-comer named Carrie Chapman Catt, an Iowa school principal turned organizer who was sent west to help them. Victory at last came to Colorado’s women in 1890, when men voted in a general election to enfranchise women. Idaho followed in 1896.