DESPITE SOME success in the West, the campaign for suffrage slowed down in the 1870s and 1880s. Americans’ zest for reform after the Civil War began to cool down. The United States entered its Gilded Age, when the men who ran big business—iron, steel, railroads, meatpacking, and oil—launched America into years of growth.

To get that job done, business and industry needed workers for factories and offices.

Companies grew so big the men in charge never met most of their workers face to face. Corporate bosses had no contact with the women and men who ran spoolers in cotton mills or pulled steel from blast furnaces. Companies squeezed out as much work as they could from their employees. Typical workweeks ran 10 to 12 hours a day, every day but Sunday. Often there was no place to sit down, no fresh air, and no time to take a break.

From the beginning, women worked many of the same jobs as men but with far less pay. Until Massachusetts changed its laws in 1874, women and children worked six days a week, just like the men did.

The swell of new immigrants from Eastern Europe, Russia, and Italy offered industry a supply of cheap labor, and immigrant women did their part on production lines. Others scraped out a living doing piecework at home as seamstresses for the garment industry or as cigar makers in overcrowded city tenements that overflowed with people and garbage.

Growing businesses needed clerical workers to staff their offices and hired well-schooled women as copyists to handwrite letters and documents. Once typewriters were invented, women became typists. Companies needed someone to do their paperwork, but a typist’s job was nonetheless considered low-level work.

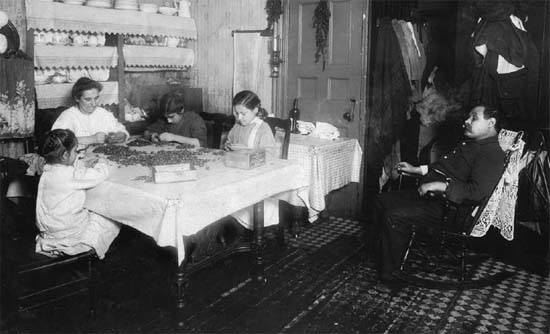

Tenement families did piecework at home. In this photo, children ages 10 and 5 help to pick nuts from their shells. The father, laid off from the railroad, refused to do piecework.

Tenement families did piecework at home. In this photo, children ages 10 and 5 help to pick nuts from their shells. The father, laid off from the railroad, refused to do piecework.

Library of Congress LC-DIG-nclc-04143

As late as 1917, girls like this 15-year-old worked as typists. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-47377

As late as 1917, girls like this 15-year-old worked as typists. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-47377

Whether office workers or shop clerks, most young women left their jobs when they married. As before the Civil War, married women in the growing middle class were expected to live in their domestic sphere, seeing to their husbands’ needs and raising their children.

SOCIALLY AND politically, life for women in the Gilded Age changed slowly. Victorian ideals still reigned. Though more girls went to school and a lucky few to college, many American girls did not stay in school much past age 10.

Girls didn’t play sports or exercise much beyond going for walks. Pale faces were fashionable. Ladies kept their hats and gloves on to keep the sun from their faces and hands, and they practiced good posture, held up in part by corsets lined with steel rods.

Middle- and upper-class women were wrapped up in undergarments and fashions that made them prisoners in their own clothes. Even hardworking farm women, as well as immigrants who worked as servants and factory workers, had to put up with long, heavy dresses.

“Sensible mothers” wore corsets, as did their children—or so this ad claimed.

“Sensible mothers” wore corsets, as did their children—or so this ad claimed.

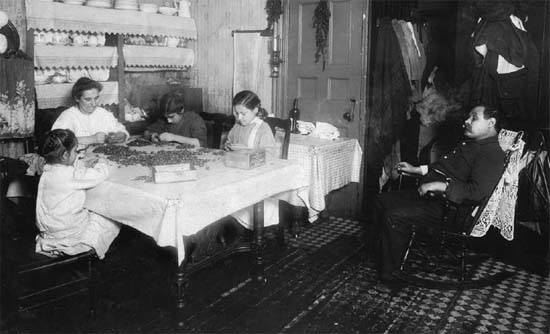

An image from 1903 shows a woman’s internal organs in their natural space (left) and squeezed by a corset (right).

An image from 1903 shows a woman’s internal organs in their natural space (left) and squeezed by a corset (right).

Library of Congress LC-DIG-ppmsca-02907

FASHIONS in the 1800s dictated that women and older girls wear corsets to draw in their waist to tiny proportions.

But how did they feel? You can experiment with a bandage designed to wrap an injured ankle, knee, or elbow. But for this activity, you’ll wrap it around your middle.

You’ll Need

Put on the tight T-shirt and leggings. Ask your helper to wrap the bandage around your middle. Lift your arms. Start by holding the end of the bandage on your chest, as shown. Once your helper has made one wrap, lift your arms away from your body.

Your helper makes more wraps, working down your middle. To create your “waist,” each wrap should be tighter and tighter. When your helper has finished wrapping, the wraps should end below your belt line.

Your helper should fasten the end of the bandage to itself using the metal clips.

How do you feel? (At first, this might not feel too uncomfortable.) Ask your helper to take your picture, front and back. You’ll be surprised to see how different you look with your waist wrapped.

Now how comfortable do you feel? Are you able to walk and move easily with your waist wrapped?

Carefully loosen the clips and remove the bandage. Now how do you feel? Years ago, women often wore their corsets day and night. How did they ever get used to them?

Not only were clothes confining and inconvenient, but the corsets worn underneath were dangerous. Years of wearing tight corsets actually squeezed women’s lungs, stomachs, and other organs out of place. If anyone knew that, they wore them anyway. The author Laura Ingalls Wilder wrote about the corsets she had to wear in the early 1880s when she was about 14:

Her corsets were a sad affliction to her, from the time she put them on in the morning until she too\ them off at night. But when girls pinned up their hair and wore skirts down to their shoetops, they must wear corsets.

“You should wear them all night,” Ma said. Mary did, but Laura could not bear at night the torment of the steels that would not let her draw a deep breath. Always before she could get to sleep, she had to take off her corsets.

SUSAN B. Anthony may have disliked Victoria Woodhull, but she agreed with her on one count. Woodhull said that parts of the 14th and 15th Amendments did permit women to vote, precisely because their wording did not forbid it. Anthony agreed, and in the election of 1872, she, her sisters, and some friends showed up to vote at the polls in her home of Rochester, New York. That day, no one turned her away, and Anthony, together with 14 women, cast her ballot like every other man at the polling place.

Two weeks later, a lawman knocked on Anthony’s door. He arrested her for breaking a federal law by voting in a national election. The following summer, Anthony faced government lawyers in court. From the first, every onlooker knew that matters would go against her. The judge, in fact, wrote his opinion before the trial took place. He refused to allow Anthony to speak in her own defense, and he also instructed the jury—all men— to find her guilty without even a moment to deliberate behind closed doors.

Anthony was convicted and fined $100. She then told the judge, “I will never pay a dollar of your unjust penalty.” She went on to say that she would happily pay off the $10,000 debt she owed for publishing the Revolution, but she would never pay the $100 fine.

Susan’s words cut through the air. She was proud that her magazine had taught “all women to do precisely as I have done, rebel against your man-made, unjust, unconstitutional forms of law, which tax, fine, imprison, and hang women, while denying them the right of representation in the government.”

The crafty judge had his surprising answer ready. “Madam,” he said to Anthony, “the Court will not order you to stand committed [to go to jail] until the fine is paid.”

For the moment, the judge had won. Anthony never paid the fine, and no one tried to collect it. By not ordering Anthony to jail, he stopped her from appealing to a higher court of law.

Anthony and Stanton now realized that they would never win votes for women by going through the US court system. The two friends, along with the other suffragists of NWSA, decided that they must persuade Congress to pass a constitutional amendment. In January 1878, a helpful senator introduced a 16th Amendment to the Constitution. Anthony penned its 24 words: “The right of citizens to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

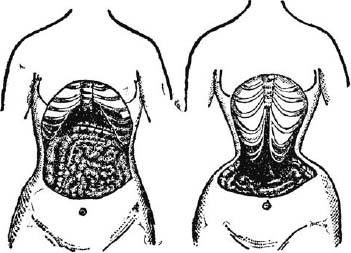

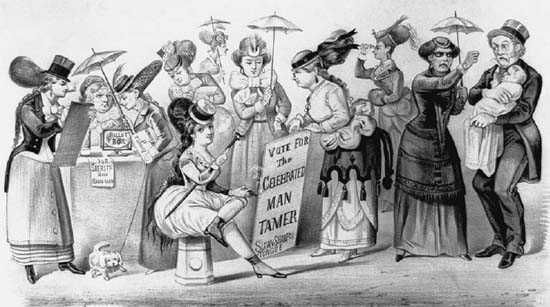

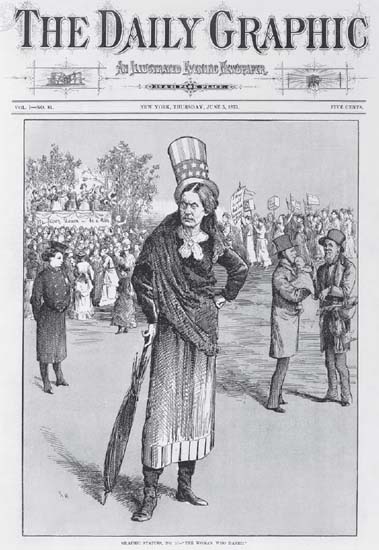

An 1869 cartoon, “The Age of Brass,” made fun of nervy women who wanted to vote.

An 1869 cartoon, “The Age of Brass,” made fun of nervy women who wanted to vote.

Library of Congress LC-USZ62-700

IN the 1800s, girls and women were restricted in their choice of art. It wasn’t considered appropriate for women to paint big pictures in oils or to carve large sculptures. Only items that could decorate homes were thought to be ladylike.

Many women who were skilled artists painted china—cups, saucers, plates, and trays. China painting was considered just a “minor” art. Still, many lovely items sit in china cabinets today, handed down from one generation to the next as family treasures.

You can try your hand at china painting too, using modern materials.

You’ll Need

To start, wash and dry the pieces you will paint. Use pencil and paper to practice designs until you create some that you like. Cover your work surface with newspaper to keep it clean.

Read the directions on the paint containers. Pour some of each color onto a deli tray. Following the directions, practice painting your designs on the foam surface. Experiment with the brushes to see what effects you can make—thin, thick, smooth, rough. Also practice mixing and blending colors—that’s part of the fun. Remember, practice makes perfect!

Are you ready? Use a washable marker to trace your design onto a piece of china. Carefully add the paint. Allow one layer to dry before you add another. If you don’t like what you see, don’t worry. You can wipe the fresh paint away and start over.

When you are pleased with your work, it’s time to set the paint in by heating the china in the oven. An adult should help you with this step.

Read the directions on the paint containers for finishing your piece. Turn on the oven and set it at the correct temperature.

The adult should help you put your piece in the oven. Set the timer. Remove the piece when time’s up. Be sure to use oven mitts.

You are now ready to use your piece of painted china. You can decorate vases and pots and other items as well.

In 1878 and every year thereafter until 1919, these words were presented to the US Congress. In time, it became known as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment. But by the time it passed through Congress and was ratified by the states, both Susan Anthony and Elizabeth Stanton were long dead.

FOR THE moment, the drive for women’s suffrage seemed to have run out of steam. Though their hearts stood strong to their task, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony were growing old, as was Lucy Stone. “The cause” was in the doldrums, like a huge ship adrift at sea with no wind to fill its sails.

The outspoken ladies who stood front and center for suffrage represented only a fraction of American women. Many homemakers stood in the mainstream with other Americans. The plain truth was that most middle-class women didn’t care much about having the right to vote.

A pictorial newspaper poked fun at Susan Anthony after she was convicted in a US court for voting. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-114833

A pictorial newspaper poked fun at Susan Anthony after she was convicted in a US court for voting. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-114833

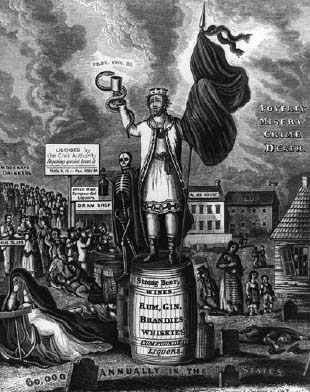

“Poverty, Misery, Crime, Death”—”King Alcohol” ruined lives in many American families.

“Poverty, Misery, Crime, Death”—”King Alcohol” ruined lives in many American families.

Library of Congress LC-USZ62-90655

True enough, more girls and young women were going to high school and college. But once they married, most middle-class women were content to work at home and raise their families. They did not cross the invisible line that separated them from the world of men. By tradition, America’s “true women” were taught to believe that they were responsible for keeping the nation’s morals in good shape. In “polite” society, women were believed to be purer than men.

Ministers in pulpits and politicians in government agreed that America’s women must stay pure and untouched by the world beyond their doors. They saw no need for women to take part in public life. Their husbands were there to shield them from the corruption on American streets and in American business.

And yet, when some homemakers found their very way of life at risk, they began to change their views about getting into politics.

The threat was alcohol. Strong drink— rum, whiskey, and bourbon—ruined the lives of many. Drunkenness was an issue across America. All too often, men who went on drinking binges came home to beat their wives and children. Fathers and husbands ended up fired from their jobs.

As keepers of their homes and families, women didn’t have jobs to bring in money, or any way to hire lawyers to protect themselves. That left many women and children hungry and often homeless.

A lot of these luckless women had grown up believing what they heard in church: that God’s plan for the world was for men to have power over their wives and children. But the Bible didn’t offer a clear solution for women whose husbands were sickened by alcohol. Some women were devoted churchgoers, and they prayed for God’s guidance as they looked into their own souls for answers. There they found them—they broke with church tradition and decided to step into the public sphere to call for prohibition and ban alcoholic drinks across the nation.

Ordinary housewives began to speak in public and petition their town and state governments. For a time, prohibitionist women won some victories. Yet when they spoke in public, men jeered and catcalled.

One minister called these women “a monstrosity of nature, a subverter [threat] of society, the cave of despair, the head of Medusa.” To this man of God, a woman who spoke in public was as frightful as a monster in a Greek myth with snakes for hair.

Like women who had spoken out against slavery 40 years earlier, female prohibitionists found they had no true voice. All too often, the daily grind of local politics took place in beer-soaked saloons where no “nice” woman with good morals was welcome.

Frances Willard led the charge for prohibition as leader of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. Willard understood that winning prohibition was a political issue as well as a moral one. In her eyes, women were keepers of America’s virtue, but it was no good keeping women behind closed doors.

Willard agreed that women must have the vote. By linking prohibition with suffrage, she cracked open the door to new ideas.

For the first time, American women who hadn’t thought much about winning the vote began to change their minds. Into their white ribbons that stood for purity, they twisted the yellow ribbons of suffragists. As the 1870s and 1880s rolled on, many mainstream American women joined the suffrage movement.

Willard’s push for the vote had both pluses and minuses. For one, suffragists now had more members to back them and more money at hand. But when Willard linked prohibition with winning the vote, women’s suffrage gained even more enemies. As always, powerful men in the liquor business had no intention of closing saloons and banning alcohol.

As AMERICAN life prospered, middle-class women began to have fewer children, which freed them to spend time away from home. A few free hours during the week allowed women to socialize at their churches and join clubs in their communities. Gardening clubs, library societies and book clubs, missionary and prohibition groups—in big cities and small towns—welcomed women to share their interests.

In parlors at homes across America, millions of women began to find a voice in their communities. Many women were eager to stretch their minds and learn new things. Women read up on topics and then wrote long reports to deliver at business meetings. They read and reported on all kinds of subjects from music to missions to Greek literature to important political and social issues, suffrage among them.

Frances Willard.

Frances Willard.

Library of Congress LC-USZ61-790

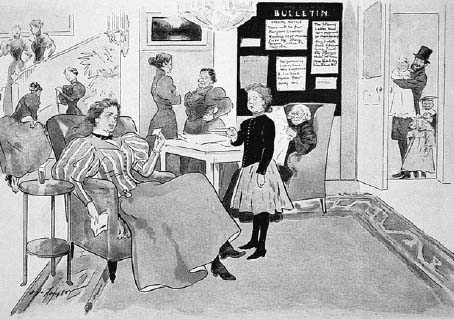

Puck magazine made fun of women’s clubs. This cartoon compares a women’s club with men’s clubs that were popular in the late 1800s. Library of Congress LC-USZC2-1021

Puck magazine made fun of women’s clubs. This cartoon compares a women’s club with men’s clubs that were popular in the late 1800s. Library of Congress LC-USZC2-1021

Most women’s clubs, including many church groups, stayed independent of men’s influence. Women thought of their clubs as part of their sphere and proudly raised money and ran their budgets independent of their husbands.

Club women typically put on an appearance as “do-gooders” in their cities and towns. They raised money for orphanages and sewed clothes for the poor. By masking their work as charity, they kept men from interfering with their chance to simply enjoy using their minds.

Whatever their interests, club women had one thing in common: they took time from discussing business to socialize over cups of tea and plates of cake and cookies. “Ladies, we must eat and drink something together or we shall never get acquainted with each other,” proclaimed Julia Ward Howe, who besides being a suffragist prized her friendships with women in her clubs.

Women joined clubs according to their interests, but their clubs also mirrored American life. Protestant, Mormon, and Jewish women had their own clubs, as did working-class women and newly arrived immigrants. Other groups of Catholic and Southern Baptist women joined clubs but did not enjoy the same independence from the men who ruled their churches. In any case, women rarely socialized with members of other faiths. Protestants spent time with Protestants, Catholics with Catholics, and Jews with Jews.

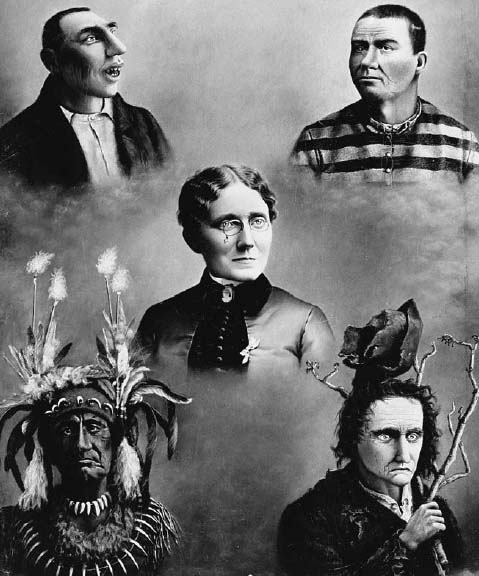

“American Woman and Her Political Peers.” In 1893, Henrietta Briggs-Wall designed this image of Frances Willard surrounded by others not allowed to vote. They are a mentally disabled man, a criminal, an American Indian, and a madman. Kansas State Historical Society

“American Woman and Her Political Peers.” In 1893, Henrietta Briggs-Wall designed this image of Frances Willard surrounded by others not allowed to vote. They are a mentally disabled man, a criminal, an American Indian, and a madman. Kansas State Historical Society

WOMEN’S CLUBS also divided themselves by race along the color line. In the 1800s and long into the 1900s, race divided the United States. In the South, state governments made laws that forced black Americans to live apart from whites. These laws, known as Jim Crow laws, established segregation as a way of life.

In the North, Americans also divided themselves by race. Though Jim Crow laws did not officially segregate blacks and whites, an invisible wall separated the races. Blacks and whites worshipped in separate churches, got their hair cut in separate barbershops, attended different parties, and mostly attended separate schools.

Most middle-class whites viewed all blacks as ignorant and inferior, even those who were well educated and worked as doctors, lawyers, and teachers. Middle-class blacks had to constantly prove their worth to whites. In late 1800s America, whites and people of color did not socialize.

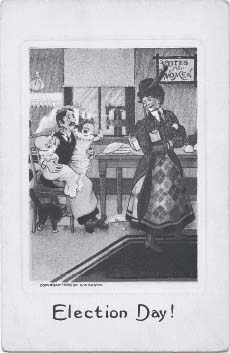

SUFFRAGE postcards used humor to make their point.

What do you have to say about our world? Is something going on that you want to change? Perhaps you’d like a better playground where you live. Maybe there’s a need for your town to have a community garden or a place where people can play checkers and chess. What about bike trails?

Put your idea on a postcard, add a stamp, and mail it. Be sure On the back, write your message on the to make your postcard from sturdy card- left side, as shown. Be polite, and say thank board, or buy a plain postcard at the post you. Address the card and add a stamp. office. Your postcard must be:

This postcard appeared in 1906, well before women won the vote.

This postcard appeared in 1906, well before women won the vote.

There are many ways to express your thoughts. Here are a few suggestions:

On the back, write your message on the left side, as shown. Be polite, and say thank you. Address the card and add a stamp. Be sure to research exactly who should receive your postcard.

Note: If you decorate your post card, have it weighed at the post office before you mail it.

Black women faced a double struggle: to achieve their rights as people of color and also to combat their second-class roles as women. Like white women, black women banded together in the late 1800s to form church groups and clubs. These like-minded women shared the same plans to provide better schools, good jobs, and other reforms to improve life in black communities.

In 1896, a number of influential women’s groups banded together to form the National Association of Colored Women (NACW). As their motto they chose inspiring words: “Lifting as We Climb.” Several influential suffragists joined them. They included the scholar Mary Church Terrell, journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett, and Harriet Tubman, now 74 years old and a living legend.

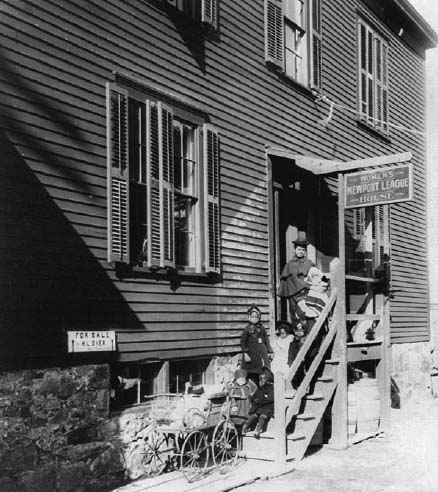

Children and a caregiver stand on the steps of the Women’s Newport League House, a day nursery. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-51556

Children and a caregiver stand on the steps of the Women’s Newport League House, a day nursery. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-51556

These young women were officers of the Women’s League of Newport, Rhode Island. This club for black women worked to improve the community. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-51555

These young women were officers of the Women’s League of Newport, Rhode Island. This club for black women worked to improve the community. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-51555

When it came to votes for women, NACW members were more vocal than white club members. Black women were sure that having the vote would help them change society. In 1912, NACW went on record to support women’s suffrage. Their white counterpart, the General Federation of Woman’s Clubs, did not endorse women’s suffrage until 1914.

Mary Church Terrell was born in Memphis, Tennessee, during the Civil War to parents who had once been enslaved. Her father became a successful businessman in segregated Memphis. He realized that his daughter could not get the education she deserved at home and sent Mary north to Ohio to go to school.

Like Lucy Stone before her, Terrell attended Oberlin College, as always welcoming to both women and people of color. Graceful and smart, she studied classics at college and learned to read and write French, German, and Italian. She put her flair for languages to use throughout her life, especially when she represented black women at a meeting in Germany in 1904. Terrell became the talk of the conference when she presented her views in three languages, the only delegate with such talent.

Terrell’s far-ranging interests marked her as a strong progressive. She served as the first president of the National Association of Colored Women and later helped to found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). She also taught in schoolrooms and colleges and became the first black woman to serve on a school board in Washington, DC. She and her husband, a lawyer who rose to become a judge, welcomed two daughters into their family.

Terrell’s gift for speaking made her a popular figure at lectures and conferences. She pushed her views about the dignity of black women and equality for all people wherever she went. At the age of 89 in 1952, Terrell hobbled into a whites-only cafeteria in a dime store, leaning on her cane. No one would serve her a meal. Still, she had made her point.

Mary Church Terrell. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-54722

Mary Church Terrell. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-54722

But times were changing. Months later, the manager of the same cafeteria invited her back for a visit, where he treated her to coffee and a piece of pie.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton hated to hear ministers preach that women were evil. Their views, she claimed, shamed women.

When our bishops, archbishops and ordained clergymen stand up in their pulpits… with reverential voice, they make the women of their congregation believe that there really is some divine authority for their subjection.

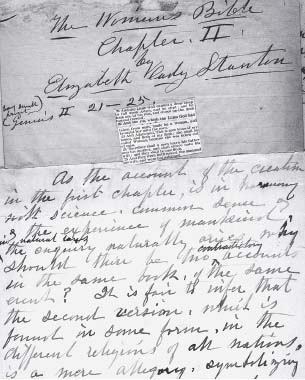

In 1895, Stanton and others published the Woman’s Bible. They hoped to correct mistakes in people’s thinking. They pointed out that parts of the Bible said different things.

For example, one passage said that God created Eve, the first woman, from Adam’s rib—which made her second in God’s eyes. However, Stanton noted, in the very first creation story, God created Adam and Eve at the same time—as equals.

The Woman’s Bible also challenged another belief. In his Letter to the Corinthians, the apostle Paul wrote that women “should be quiet in church.” Churchmen used this verse to stop women from serving as ministers or priests.

But as reformers pointed out, the very same Paul also wrote, “There can be neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female.” Common sense said that the Bible’s words must be open to new ways of understanding.

Susan Anthony was dismayed when Stanton published the Woman’s Bible. Anthony welcomed women of all faiths, as well as nonbelievers. She did not want the Woman’s Bible to draw fire on the suffrage movement.

A manuscript page of the Woman’s Bible penned by Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Library of Congress

A manuscript page of the Woman’s Bible penned by Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Library of Congress

Young suffragists feared that Stanton’s far-reaching views would make them outcasts. They voted to censure—formally criticize—Stanton at their annual meeting. Anthony could not stop them.

From then on, Stanton pulled away from the suffrage movement. She continued to write and publish her freethinking ideas, and she never regretted them. But as the suffrage movement pressed on, Stanton was nearly forgotten.

In the 1920s, when a new generation of women recorded the history of women’s suffrage, Elizabeth Cady Stanton was “written out” of the story. The authors idolized Anthony, and they lied about some of her deeds in order to build up her name. These writers claimed that Anthony had attended the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls in 1848. That was not true, and they knew it. Several decades passed before students of the women’s rights movement gave Elizabeth Cady Stanton her rightful place in history.

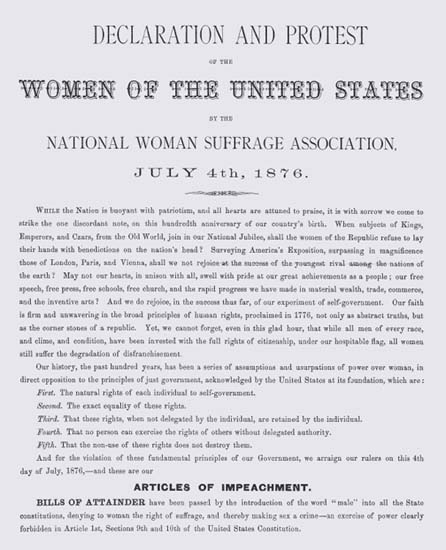

IN JULY 1876, Americans celebrated the 100th anniversary, the Centennial, of the Declaration of Independence. To Elizabeth Stanton and Susan Anthony, however, it seemed there was little to celebrate because women still had no right to vote. Together with their loyal friend Matilda Joslyn Gage, they rewrote their Declaration of Rights for Women, and Anthony asked to present it at the official celebration in Philadelphia. She was told no. There weren’t any seats, claimed the men in charge.

On July 4, 1876, Anthony and four friends finagled their way into the giant convention hall. As the Declaration of Independence was read aloud, the five women rose from their chairs and headed toward the stage. Anthony handed a parchment copy of the women’s declaration to none other than the acting vice president of the United States, Thomas Ferry. The other women handed out copies to men in the audience.

Uninvited, Susan B. Anthony and others passed out copies of this document to men celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Library of Congress rbpe 16000300

Uninvited, Susan B. Anthony and others passed out copies of this document to men celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Library of Congress rbpe 16000300

DID you ever hear this nursery rhyme?

Miss Lulu had a baby, she called him tiny Tim.

She put him in the bathtub, to see if he could swim.

He drank up all the water! He ate up all the soap!

He tried to swallow the bathtub, but it wouldn’t go down his throat!

Call for the doctor!

Call for the nurse!

Call for the lady with the alligator purse!

“Mumps!” said the doctor. “Measles!” said the nurse.

“Vote!” said the lady with the alligator purse!

Volunteers at the Susan B. Anthony House in Rochester, New York, will tell you that the “lady with the alligator purse” was none other than Anthony herself. Her purse, actually a roomy handled bag made of alligator skin, went with her everywhere. In the 1890s, Anthony spent several months in California helping its women work for suffrage. Anthony went home without success in California, but her alligator purse left an impression. Children picked up on Anthony’s fame and added it—and her handbag—to their jump-rope rhyme.

Get some exercise as you chant this enchanting rhyme.

You’ll Need

Practice saying the rhyme until you have it memorized. Think about how it will fit the rhythm of jumping rope—especially line 4. When you are ready, grab your rope and go outside. Have fun jumping. Can you imagine Susan Anthony jumping rope when she was young?

susan b. anthony house, inc.

susan b. anthony house, inc.

With that task done, Anthony went outside and climbed onto a bandstand in the humid July day. Her friend Matilda Gage held an umbrella to protect the black-clad Anthony from the sun. People gawked at the 56-year-old woman, dressed in black, who spoke powerful words:

And now, at the close of a hundred years, as the hour-hand of the great clock that marks the centuries point to 1876, we declare our faith in the principle of self-government, our full equality with man in natural rights; that woman was made first for her own happiness, with the absolute right to herself.

AS THE nation marked its centennial, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony took stock of their own drive for independence. Anthony was 56; Stanton, nearly 61. In their day, they were thought of as old women. It was time to get their story down on paper.

Working as a team, Stanton and Anthony began to write A History of Woman Suffrage. As Anthony wisely pointed out, men had been busy writing their history for centuries, and it was high time for women to do the same. Over the course of several years—well into the 1880s—Stanton and Anthony, sometimes assisted by Matilda Gage, wrote three enormous volumes. Eventually A History of Woman Suffrage grew into six books stuffed with details about women’s struggle to win the vote—but they were finished long after Stanton and Anthony had died.

Often the friends would disagree as much as they agreed about what to write. Sometimes their writing sessions morphed into arguments, and Anthony would leave Stanton’s house to take a walk and give them both time to cool off.

Their disagreements mirrored the differences in their thinking. Anthony, growing older but still filled with fire, fixated on suffrage only; she was sure that once women had the vote they could make America a better place.

Stanton’s views grew ever broader. To Stanton, having the right to vote was not enough, only “a crumb” and not a whole loaf. Stanton wanted girls and women to have options in their lives—in their education, their choice of a trade or profession, and their family lives (whether to use birth control to manage the size of their families).

Elizabeth Cady Stanton had one more radical idea. She wanted society to agree that, in God’s eyes, women stood equal with men.

Though they often argued about the best way to win rights for women, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton stayed friends for life.

Though they often argued about the best way to win rights for women, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton stayed friends for life.

Library of Congress mnwp 159001