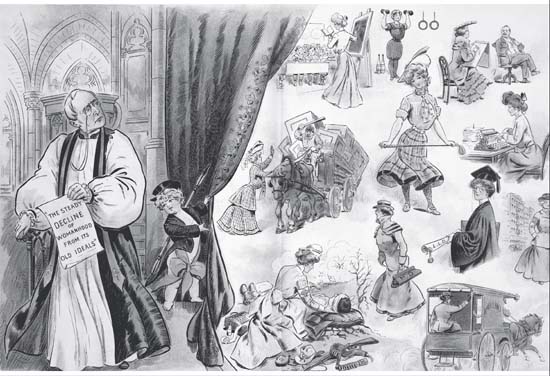

At the turn of the 20th century, American women stepped more and more into public life. This illustration depicts the different roles they took on.

At the turn of the 20th century, American women stepped more and more into public life. This illustration depicts the different roles they took on.

Library of Congress LC-DIG-ppmsca-25811

ELIZABETH CADY Stanton wanted to add Lucy Stone’s contributions to the book she was writing with Susan B. Anthony. Stanton wrote Stone asking for her help, but Stone wrote back to say no. Their differences were too many, the divide between them too deep.

Thus, at first, Lucy Stone’s story and the history of the American Woman Suffrage Association was left out of A History of Woman Suffrage. As the months moved on, Elizabeth Stanton and Lucy Stone did not solve their disagreements.

Like young women everywhere, Harriot Stanton Blatch and Alice Stone Blackwell viewed their mothers’ quarrels as ancient history. By the late 1880s, they wereadults with minds of their own, and they wanted to heal the rift in the suffrage movement.

Lucy Stone was honored with a stamp by the US Post Office in 1968.

Lucy Stone was honored with a stamp by the US Post Office in 1968.

Blatch came to her mother and Susan Anthony with a suggestion for their history book. Blatch believed that Lucy Stone’s work needed a place, and she offered to write the missing chapter about Stone and AWSA.

Anthony never warmed to the idea, but Blatch wrote it anyway. Blatch’s mother, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, made sure that Anthony paid Blatch for her contribution.

Alice Stone Blackwell was no fan of Susan Anthony, but she also felt that it was time for both sides to come together. She and her father, Henry, nudged their friends toward reuniting with their enemies. Time was marching on, and Lucy Stone agreed that the stories of old battles between suffragists didn’t matter to younger women.

IN 1890, America’s suffragists reunited as the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Once not on speaking terms, Stanton, Anthony, and Stone regrouped as leaders of their party. But the relationship among them was never easy. It was up to the next generation to take up the cause of women’s suffrage and work together.

Lucy Stone’s health had started to fail, and in 1893, she died. Her lovely voice, so long a force for women’s suffrage, was stilled. Stone, who had refused to take her husband’s name so long ago, pioneered another change at her death. She was the first person in Massachusetts to ask that her body be cremated instead of buried.

Henry granted her wish, and Stone’s ashes were buried in a cemetery without a gravestone. But her voice survives in the thousands of letters she wrote to Henry, Alice, and scores of others. When she died, she left her orders with Alice in her final words: “Make the world better.”

IN order to raise money, suffragists in Boston turned to a tried-and-true fundraiser— they wrote a cookbook. As busy as they were, suffragists still had families to feed.

The Woman Suffrage Cook Book, published in 1886, offered recipes from appetizers to desserts, as well as a section on cooking and personal care for the sick. Some famous names appear—Lucy Stone, Alice Stone Blackwell, Dr. Anna Howard Shaw—as well as ministers and everyday women who proudly called themselves suffragists.

Alice Stone Blackwell’s recipe for Water-Lily Eggs sounds much like a recipe that appeared in the 1900s for Eggs à la Goldenrod. An older person in your family might remember them as a special treat.

You can enjoy Alice’s delicious offering for breakfast—or anytime! Read Alice’s original recipe, and then try the updated one.

ALICE STONE BLACKWELL’S WATER-LILY EGGS

Boil two eggs twenty minutes. Separate whites from yolks. Put on a plate one teaspoonful of flour, a piece of butter the size of a hickory nut, and pepper and salt to taste. On this plate cut up the whites of the eggs into small cubes the size of dice, mixing with flour, salt, etc. Have four tablespoonfuls of milk boiling in a sauce-pan; put the whites in, and let them cook slowly while you make two slices of toast. Spread whites (when flour is thoroughly cooked) over toast. Break the yolks up slightly and salt them, and force through fine strainer over the whites on top of the toast. Holes in strainer should not be larger than pinheads. Serve hot, at once. A very pretty dish, and convenient in case of unexpected company, as bread and eggs are almost always in the house.

—ALICE STONE BLACKWELL.

UPDATED WATER-LILY Eggs

You’ll Need

To boil the eggs, place them in a small saucepan and cover with water. Bring the eggs to a boil, turn down the heat, and simmer for 20 minutes. Remove the hard-boiled eggs carefully with a large spoon. Run cold water over them until you can handle them, but they should still be warm.

Peel the eggs and separate the yolks from the whites. Using the back of the spoon, force the yolks through the strainer onto a small dish. Sprinkle with a bit of salt and set aside.

To make the sauce: On the plate, chop up the egg whites and mix with the flour and butter. Sprinkle lightly with salt and pepper. Pour the milk into a small glass dish and stir in the egg-white mixture. Microwave on high power for 30 seconds. Remove and stir a bit with a small fork. Return mixture to microwave and cook again for 15 more seconds. Repeat the process until your mixture is thick and creamy.

While you are cooking the egg-white sauce, toast two slices of bread, but leave them in the toaster. (Hint: If you make toast in a toaster oven, put your breakfast plate on top to warm it. A warm plate means a warmer breakfast!)

When the egg-white sauce is ready, assemble your water lily. Butter the toast and place on a warm plate. Pour the sauce over the toast and sprinkle with the egg yolks.

As Alice Stone Blackwell said, enjoy this “pretty dish”!

Life in tenements was hot and crowded, as this 1882 illustration showed. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-75193

Life in tenements was hot and crowded, as this 1882 illustration showed. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-75193

THE SHINE on the Gilded Age began to tarnish. As the United States moved into the 1890s, the economy lagged. Farmers complained they couldn’t get fair prices for their crops because railroads overcharged them for shipping. In cities, immigrants and other poor people were packed into tenement slums and worked long hours for low pay. “Big business” seemed to rule hand in hand with corrupt legislators in city and state governments. It seemed that the rich were getting richer as working people struggled to make a living.

In 1893, trouble came to America’s railway system, which had overbuilt and overinvested in the nation’s railroads. One company failed, and a “run” on banks—when Americans rushed to turn their bank deposits into cash—followed. Like a house of cards, the system began to teeter; then it collapsed. The depression that followed was the worst that any American had ever seen. About one out of every six workers was left without a job.

Misery fell on big cities where immigrants lived. Packed into tenements with few laws to protect them, these foreign-born workers—men, women, and children—could not improve their lives. Other Americans, forgetting that their own ancestors had also immigrated, looked down on these newcomers. They made fun of their clothes, their languages, and their religions. Most immigrants coming from Italy were Roman Catholic; others arriving from Poland and Russia were Jews.

BY 1890, the situation in America’s slums was turning desperate. Yet some Americans strived to make better lives for others. The best-known reformer was a woman, Jane Addams, whose work with poor immigrants in Chicago sparked a national movement.

Like many women who graduated from college in the Gilded Age, Addams became a well-educated lady without a job. She drifted from one thing to the next, studying medicine for a time but always returning home to her family. They were perfectly content to have her there.

When Addams was 27, she and her lifelong friend Ellen Starr sailed to England. A chance visit to a settlement house in the slums of London transformed her life. There, at Toynbee Hall, upper-class people and poor Londoners could come together to work for social reform.

With one look at Toynbee Hall, Addams knew she had found her life’s calling. In 1890, she and Starr bought an old mansion that had belonged to a wealthy Chicagoan, and they named it Hull House in his honor. They moved in and opened their doors to their immigrant neighbors. Addams recruited other college women to help her, and within a year 2,000 poor people came to Hull House to enrich their lives. America’s Settlement Movement was born.

Addams welcomed everyone into her rambling home. Hull House sat in Chicago’s 19th Ward, whose population reflected the mix of people in American cities—”Americans, Belgians, Bohemians, Canadians, Danes, English, French, Germans, Greeks, Hollanders, Hungarians, Irish, Italians, Lithuanians, Mexicans, Norwegians, Poles, Russians, Scots, Spaniards, Swedes, Swiss, Welsh, Negroes, Chinese, and divers [diverse] odds and ends.”

Addams ran a kindergarten, kids’ clubs, and night school for adults. She taught cooking and home health care. Hull House offered a library, swimming pool, drama club, and job center. All the while, Addams stormed rich Chicagoans, pleading for them to provide the money she needed to help her visitors.

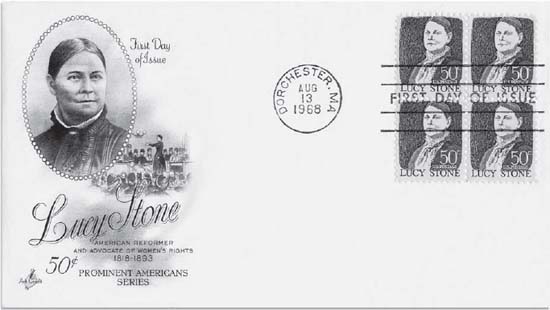

Jane Addams. Library of Congress LC-B2-107-6

Jane Addams. Library of Congress LC-B2-107-6

For more than 100 years, little girls worked in textile mills. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-18108

For more than 100 years, little girls worked in textile mills. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-18108

Thousands of women contributed to the push for women’s suffrage, and their names appear in letters, newspaper articles, and books. Most were not household names like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucy Stone, or Susan B. Anthony.

Matilda Joslyn Gage was one of these unsung heroines. Gage worked with Anthony and Stanton to update Stanton’s Declaration of Rights for Women from her 1848 version to an updated version in 1876. A gifted writer like Stanton, Gage also worked on the early volumes of A History of Woman Suffrage.

Stanton admired Gage’s knack for “rummaging through old libraries” in search of hidden stories about women’s lives. Gage believed that male writers had willfully cut women’s contributions out of the pages of history. It was a woman, Catherine Littlefield Greene, who invented the cotton gin, Gage wrote, not Eli Whitney.

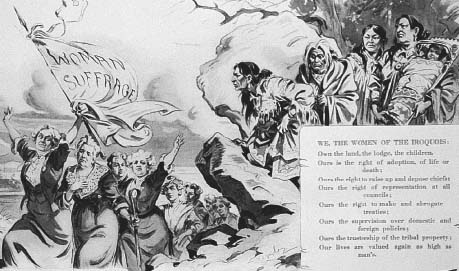

Gage had an unusual friendship with Native American women of the Mohawk nation and was a member of their Wolf Clan. Gage’s own “rummaging” and research led her to write a series of articles that pointed out that women of the Iroquois nation lived nearly as social equals to men. Women bought and sold their own property, and they were entitled to keep their children if they divorced their husbands.

Gage’s children grew up with independent minds. When her daughter Maud dropped out of law school to marry an author, Gage was dismayed. Still, she moved into her daughter and son-in-law’s home, where they had spirited talks about American life. The young man’s name was L. Frank Baum, and in a 14-book series for young people, he created a magic land where women were equal to men and everyone was ruled by a wise witch. He titled his first book The Wizard of Oz.

This cartoon points out that Iroquois women, considered “savages,” had rights denied to other women. The suffragist carrying a staff is probably Matilda Joslyn Gage. Library of Congress LC-USZC2-1189

This cartoon points out that Iroquois women, considered “savages,” had rights denied to other women. The suffragist carrying a staff is probably Matilda Joslyn Gage. Library of Congress LC-USZC2-1189

Like her ally Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Gage held radical views about organized religion and had harsh words for church teachings that kept women under the rule of men. Her outspoken personality made her enemies among other suffragists who feared that her bold ideas would threaten their work. As with Stanton, Matilda Joslyn Gage was “written out” of suffrage history until the 1990s, when scholars brought her work to light.

While Addams operated Hull House, a series of energetic, creative women walked through her door. Susan Anthony came calling, as did women who backed labor reform. Addams became a suffragist and a friend of “working girls,” working-class women who labored in factories and sweatshops.

As time went on, Addams became convinced that social reform was her true vocation. She got involved in everything from Chicago’s schools and garbage collection to fighting the sordid business in illegal drugs. Then she went national.

As a reformer, Addams became the foremost example of a suffragist working at a job. She had goals to reach, both for Hull House and for America itself. To meet her aims, she needed the right to vote. How else was she to have a voice in the halls of government?

AS THE 1890s wore on, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, now in their 70s, could not keep up with the physical demands of travel and meeting the public. But there were promising candidates to step up as suffrage leaders.

First, Anthony tapped Carrie Chapman Catt. Catt made a name for herself in Iowa’s prairie towns helping women to win the vote. Before they married, she and her husband agreed that Catt would have four months every year to travel and campaign for the women’s vote. George Catt stood firm in his stand for women’s rights and took pride in his wife’s work.

George Catt became ill not long after Carrie Catt took over as NAWSA’s leader in 1900. She returned to his side to care for him, and Anna Howard Shaw stepped up as the association’s new president.

Shaw, both a doctor and a minister, electrified audiences with her powerful speeches. However, Shaw lacked the same gift for organizing suffragists that sparked the careers of Susan B. Anthony and Carrie Chapman Catt. Like a slow-moving train, “the cause” never stopped but for a time chugged uphill, seeming to be running out of steam.

As the new generation took over, the founders faded away. In 1902, Elizabeth Cady Stanton died in her daughter’s home. Harriot Stanton Blatch told the tale of her mother’s final hours. Stanton insisted on rising from her bed and got dressed. Grasping a table, she acted as though she faced an audience and began to make a speech, her lips moving in silence. Not long thereafter, she died.

Carrie Chapman Catt worked for reform all her life. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-110995

Carrie Chapman Catt worked for reform all her life. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-110995

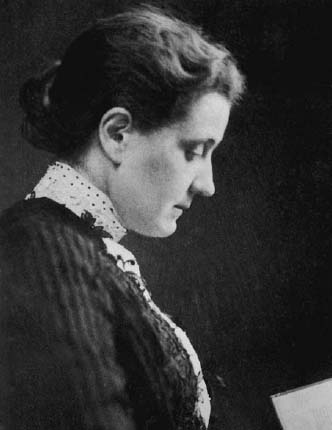

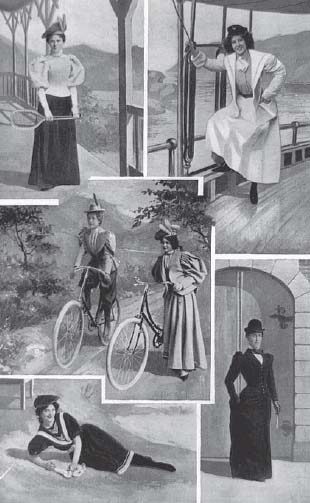

Unlike their Victorian mothers, New Women enjoyed sports like swimming, tennis, and cycling. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-83510

Unlike their Victorian mothers, New Women enjoyed sports like swimming, tennis, and cycling. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-83510

Four years later, Susan B. Anthony faced her own death at her home in Rochester, New York. Sickened by a series of strokes and a failing heart, Anthony spent her last days in bed, surrounded by her sister suffragists. As the end drew near, she mouthed the names of scores of people who had touched her life over 81 years. “Failure is impossible,” she murmured, her last words that made sense. Then she, too, was gone. It was 1906.

Lucy Stone, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony had worked their entire lives to win the vote for America’s women. Not one of them lived long enough to see her life’s work made a reality.

Anthony had tried to leave the suffrage movement in good hands, but it faltered. The grassroots push to win votes for women state by state was stuck. More than 10 years had passed since Carrie Chapman Catt had succeeded in getting men in Colorado to give its women the right to vote. When suffragists came together, their meetings looked like a minister “preaching to the choir.” Suffragists attracted only other suffragists who thought the same way they did.

Many people asked whether women needed the vote at all. Life was moving on, and women’s lives had begun to change. By 1900, Americans had become accustomed to seeing the New Woman, as she was called, at work in offices and shops. Women were welcomed in college classes and showed up as doctors, ministers, and teachers. Like men, women were free to enjoy the nation’s hot new mode of transportation: bicycling. A new twist on bloomers, bicycle suits freed them to “wheel” in comfort.

By all appearances, this New Woman had a rewarding life. She was educated and had money in her pocket. Americans idealized her as an example of womanly virtue to overcome the dark morals of money-grubbing men.

Americans prized the accomplishments of women like Frances Willard and Jane Addams who used their influence to make America a better place. They looked to both reformers as examples of perfect womanhood, who stood far above the grime of street politics and smoky saloons. Why should these perfect women dirty their hands with politics?

Willard and Addams did not agree. They were perfectly happy to win the vote—even if their hands got dirty in the process.

THESE WERE new days for women at the bottom of the social ladder as well. Men who organized labor unions had little regard for women who worked in factories. Most believed that working women took jobs away from men—and that having women in the workforce lowered pay for everyone.

IN the late 1800s, suffragists built up their spirits at their meetings by singing. There are many copies of suffrage songbooks tucked away in family attics and libraries. Songs about women’s suffrage also appeared as popular sheet music in the 1900s and were sung by popular artists of the day.

Build your spirit for women’s suffrage. Here are three songs you will recognize with no problem. They are sung to tunes you should already know!

DARE YOU Do IT?

Sung to the tune of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”

There’s a wave of indignation

Rolling ’round and ’round the land,

And its meaning is so mighty

And its mission is so grand,

That none but knaves and cowards

Dare deny its just demand,

As we go marching on.

Chorus

Men and brothers, dare you do it?

Men and brothers, dare you do it?

Men and brothers, dare you do it,

As we go marching on?

Ye men who wrong your mothers,

And your wives and sisters, too,

How dare you rob companions

Who are always brave and true?

How dare you make them servants

Who are all the world to you,

As they go marching on?

Chorus repeats

Whence came your foolish notion

Now so greatly overgrown,

That a woman’s sober judgment

Is not equal to your own?

Has God ordained that suffrage

Is a gift to you alone,

While life goes marching on?

Chorus repeats

THREE BLIND MEN

Sung to the tune of “Three Blind Mice”

Three blind men,

Three blind men,

See how they stare,

See how they stare;

They each ran off with a woman’s right.

And they each went blind in a single night.

Did you ever behold such a gruesome sight

As these blind men?

Three blind men,

Three blind men,—

The man who won’t,

The man who can’t,

And then the coward who dares not try;

They’re not fit to live and not fit to die.

Did you ever see such a three-cornered lie

As these blind men?

WOMAN

Sung to the tune of “America”

O woman, ’tis of thee,

Hope of humanity,

Of thee we sing.

Mother of all the race,

Affection’s dwelling-place,

For thy sweet love and grace

Our plaudits ring.

No name like thy dear name,

No fame like thy fair fame,

Thy name we love;

Through all our toilsome days,

Through all our devious ways,

Be thine our grateful praise,

All praise above.

Let anguish pass away,

Let rapture reign today,

Let grace abound.

In strains of joy and mirth,

Let all the sons of earth

Proclaim thy matchless worth,

The world around.

Equal of all the race,

Take now thy rightful place

By land and sea;

We’ll scorn the tyrants’ lust,

And pledge our faith and trust

To evermore be just

And true to thee.

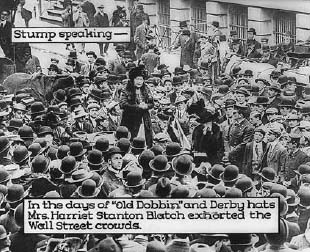

Like her mother, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Harriot Stanton Blatch hoped to change men’s minds about votes for women. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-7097

Like her mother, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Harriot Stanton Blatch hoped to change men’s minds about votes for women. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-7097

By 1900, working women had begun to find a voice, and several women-only labor unions had formed. Among their biggest fans was Elizabeth Stanton’s daughter Harriot Blatch, who was building upon her mother’s work.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton had prized the right of the individual educated woman to vote. Blatch, who lived in England and witnessed the rise of labor unions for working people, had different ideas. In keeping with her times, Blatch believed that women of all classes, from social elites to working-class laborers, should join together to push for suffrage. Blatch lived and breathed the fresh air of the Progressive Movement.

Progressivism was taking hold in the United States. Progressives found their voices during the depression of the 1890s, when the spirit of reform energized the United States.

Progressives wanted to right the wrongs they saw in American life. They pointed their fingers at everything from corrupt government officials to greedy businessmen to shady saloon owners.

Progressives lashed out at railway men who charged outrageous prices to farmers for shipping their crops to market. Progressives also criticized factory owners who expected children to work 10-hour days. Progressive government leaders battled big business, whose monopolies prevented fair trade and kept prices artificially high. Suffragists were progressives, too.

But when Harriot Blatch returned to the United States, she found the women’s suffrage movement in a “rut worn deep and ever deeper.” The suffrage movement in America had turned downright boring.

Like her gifted mother, Blatch had a flair for choosing just the right words to push her agenda. She also applied new techniques to build publicity for women’s suffrage. A “social media” pioneer in the first decade of the 20th century, Blatch decided that suffragists needed to make a splash. It was time for women to move from quiet tea parties at home to the streets of America. She organized rallies and parades, and suffragists sported cheerful purple, green, and white sashes to identify with their cause.

With escape doors locked and no way out, 146 workers died in the Triangle Shirtwaist fire.

Library of Congress LC-DIG-ppmsca-05641

A cartoonist took a bitter view of the ruins of the Triangle Shirtwaist Company. The sign on the building reads “Girls Wanted.” Library of Congress LC-USZC4-5712

A cartoonist took a bitter view of the ruins of the Triangle Shirtwaist Company. The sign on the building reads “Girls Wanted.” Library of Congress LC-USZC4-5712

Blatch made sure that the marchers encompassed women from all walks of American life. Many working-class women had joined to push for votes for women. Now suffrage parades boasted women from all rungs on America’s social ladder. Once a middle-class venture, the cause now welcomed women from all social classes, from the very rich to the working poor.

In the New York parade of 1911, the plight of working women was on everyone’s mind, whether middle class, rich, or poor. The Triangle Shirtwaist Company, a factory where workers sewed clothes, had caught on fire just two months earlier. The workers, mostly young immigrant women, died in the blaze or jumped off the roof and perished. The fire took 146 lives; the last six of the bodies were not identified until a hundred years later.

The Triangle Shirtwaist fire provided deadly evidence that America’s working women had the same right to speak their minds as did their “betters.” Well-off society women had long felt it was their duty to give money to the poor, but now both groups of women realized that they needed the vote in order to reform society.

At the same time, working women reminded their wealthy associates that working people deserved quality lives as well. One of their leaders, a Russian immigrant named Rose Schneiderman, made a speech with a rich visual image that caught people’s imaginations: “What the woman who labors wants is the right to live, not simply exist—the right to life as the rich woman has the right to life, and the sun and music and art…. The worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too.”

Rose Schneiderman also believed that she deserved the right to vote.

Despite their best efforts, suffragists ran into the same roadblocks over and over in the early 1900s. As always, the liquor industry used its wealth to influence city officials and members of Congress against woman’s suffrage.

States in the “Solid South” created another obstacle. Among their Jim Crow laws were rules that blocked black men from voting. Southern legislators, satisfied with rules that kept white men in power, had no plans to give the vote to white—or black—women. They argued that the states’ rights clause in the US Constitution permitted them to set up laws for voting.

Rose Schneiderman, a labor leader, demanded both “bread and roses” for working women.

Rose Schneiderman, a labor leader, demanded both “bread and roses” for working women.

Library of Congress mnwp.275025