Women and girls, white and black, dressed in white to march for suffrage. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-10845

Women and girls, white and black, dressed in white to march for suffrage. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-10845

ENGLAND’S SUFFRAGISTS called themselves “suffragettes.” The suffragettes launched their push for votes later than their American sisters, but when they finally organized they came on loud and strong. Led by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters, Christabel and Sylvia, suffragettes believed that their actions would speak louder than their words.

The Pankhursts and their backers used the strategy of civil disobedience. They broke laws—in nonviolent ways—in order to bring attention to the issue of women’s suffrage. They chained themselves to fences and called for the British prime minister to act. Suffragettes piled into galleries to catcall at men in session in Parliament, home to Great Britain’s House of Commons and House of Lords. They sneaked onto a royal golf course and replaced pin flags with their own suffragette ones.

By the early 1900s, even cereal companies backed the idea of votes for women.

By the early 1900s, even cereal companies backed the idea of votes for women.

British suffragettes and American suffragists were forcibly fed in prison. This image of a forcible feeding appeared in July 1912 in Popular Mechanics magazine. The Collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County

British suffragettes and American suffragists were forcibly fed in prison. This image of a forcible feeding appeared in July 1912 in Popular Mechanics magazine. The Collection of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County

Correctly guessing that this civil disobedience would get them publicity, suffragettes broke laws and landed in prison. Many went on hunger strikes, refusing to eat. In turn, prison officials struck back by forcibly feeding them, a brutal act of shoving a hose down a woman’s throat or nose and pouring liquids into her stomach.

TWO YOUNG Americans, both in England during the uproar, became suffragettes, marched with the others, and were arrested. The pair, Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, first met in a British police station where they were jailed. They went on hunger strikes and shared the torture of being forcibly fed.

By the time they were released, Paul and Burns had learned the lessons of British-style protests. Paul sailed home to the United States, ready to shake things up. Burns returned later to serve as Paul’s right-hand woman. Both strong willed, Paul and Burns vowed to battle for women’s rights in the United States.

Burns was red-haired with a loud voice; Paul was petite and quiet, but her dark eyes glowed with an intensity that was almost scary. Both were well educated. Paul grew up in a Quaker family that took women’s equality for granted and sent their daughters to college. Burns’s father also believed in educating women, and Burns was a college graduate, too. Neither Paul nor Burns liked the way American suffragists were going about their work. Paul and Burns were a generation younger than Carrie Catt and Anna Shaw, America’s leading suffragists. Catt, Shaw, and their National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) still held to their long-term strategy: win the vote state by state.

Paul and Burns, however, wanted to win suffrage with one grand act: to amend the US Constitution. Senators and congressmen were the ones standing in their way. To succeed, Paul suggested that the NAWSA suffragists establish a committee to take their cause directly to Congress. As she pointed out, “It is not a war of women against men, for the men are helping loyally, but a war of women and men together against the politicians.”

Older suffragists hesitated to approve Paul’s request for a congressional committee. Paul and Burns needed support, and they turned to none other than Jane Addams, who was regarded as an American saint. Addams advised the younger women to turn down their volume as they pushed for their ideas. But Addams agreed to back their plan, and NAWSA’s leaders accepted Paul’s request. Alice Paul’s Congressional committee set up shop.

Paul had no plans to stay quiet. In the next few years, she and Burns transformed the small committee into the powerful Congressional Union and moved into a building across the street from the White House. The White House, and the president who lived there, would become Paul’s target in winning the vote.

As Paul, Burns, and their followers became ever stronger, their activist stance became too much to handle for the moderate, well-behaved women at NAWSA. In 1915, the two groups split, and the Congressional Union took its new name, the National Woman’s Party (NWP).

Alice Paul copied the suffragette strategy she learned in Britain. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-37937

Alice Paul copied the suffragette strategy she learned in Britain. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-37937

American suffragist Lucy Burns (left) admired British suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst (center). Library of Congress LC-H261- 3299

American suffragist Lucy Burns (left) admired British suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst (center). Library of Congress LC-H261- 3299

The cover of the suffrage parade’s program was splashed with the National Woman’s Party purple and gold. Library of Congress LC-DIG-ppmsca-12512

The cover of the suffrage parade’s program was splashed with the National Woman’s Party purple and gold. Library of Congress LC-DIG-ppmsca-12512

Once again, America’s suffragists had torn apart, just as they had more than 40 years earlier. On one side stood NAWSA, middle of the road and relatively quiet in its quest for women’s suffrage. On the other was Alice Paul, backed up by Lucy Burns and the NWP, who believed in action, not words. They became militants, the rabble-rousers of American suffrage.

Taking a cue from British suffragettes, who worked against the political party in charge in London, Paul decided to go after the political party then in power in Washington, DC—the Democratic Party.

After 15 years of Republican presidents, the Democrats had won the campaign of 1912 and elected Woodrow Wilson as president. Paul’s first big effort took place on March 3, 1913, the day that Wilson arrived in Washington to be sworn into office.

When the president-elect’s train pulled into the station in the capital, there was no crowd to greet him. “Where are the people?” an aide was heard to ask. “Over … watching the suffrage parade,” came the answer.

Paul had upstaged Wilson by holding a parade on the very same day. Eight thousand strong, the parade wound down Pennsylvania Avenue. At the front rode a woman on a white horse. There were floats and bands, foreign delegates, male suffragists, college students, factory women, and representatives from Howard University, a local black college. To keep the parade about suffrage and not about race, these African American women were mingled with the male marchers at the back.

On the steps of the US Treasury Department, women in white staged a tableau, with the figure of Columbia as their leader. Standing silently, these costumed performers portrayed American ideals: liberty, charity, justice, peace, and hope among them.

Half a million people crowded the parade route. Some were there to watch, but others were there to make trouble. Plenty of men despised the thought of women getting the vote. Pushing and shoving and name-calling began, and as the parade wound on, things fell apart and turned ugly.

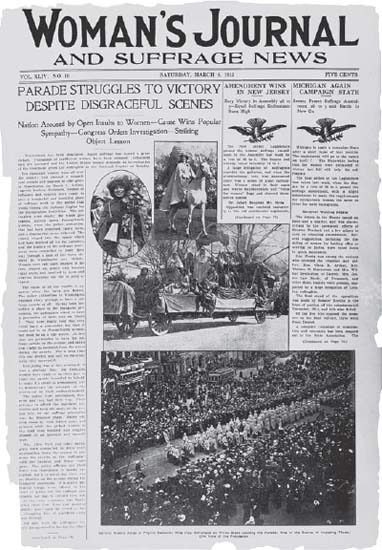

The Woman’s Journal reported the following:

Women were spat upon,… [s]lapped in the face, tripped up, pelted with burning cigar stubs, and insulted by jeers and obscene language too vile to print or repeat.—”Rowdies seized and mauled young girls.”—”A very gray-haired college woman was knocked down.”—”The parade was contin ually stopped by the turbulence of the crowd.”

One of the African American women who marched in the Washington suffrage parade did not do as she was told. Ida Wells-Barnett was a member of the Illinois suffrage delegation who traveled to Washington to join in the suffrage parade.

When she arrived, parade organizers told her that she could not march with the rest of the delegation, which was made up of white women. As a black woman, she must march with others like her at the end of the parade. But Wells-Barnett had a different idea. She mingled with the crowd, and when the Illinois women marched past, she walked into the street and joined in. Nothing was going to stop her from marching with Illinois’s suffragists.

Wells-Barnett was a member of America’s small but well-educated black middle class. Born Ida B. Wells, she made her name by refusing to give up her seat in a whites-only railroad car. She was one of the first American women to join her maiden and married names with a hyphen.

Wells-Barnett was a journalist, and she worked to improve the lives of black women and men in segregated America. Above all, she was known to black Americans for her campaign to stop the horrible practice of lynching.

Ida Wells-Barnett.

Ida Wells-Barnett.

Library of Congress LC-USZ62-107756

In the segregated America of the late 1800s and well into the 1900s, lynching was an act of terror carried out by whites against blacks. White mobs kidnapped and killed black men by lynching—hanging—them. The mobs justified their brutal actions by saying that their black victims had committed terrible crimes.

Wells-Barnett used the power of her pen to bring these cruel acts to America’s attention. An ardent suffragist, Wells-Barnett believed winning the vote would fortify her work.

The police stood by and did nothing to help. One hundred people went to Emergency Hospital. In the midst of all the confusion, one thing now was clear. The women’s suffrage movement was going to cause a fuss.

Suffragists staged a tableau at the US Treasury Department steps during their monumental parade in Washington, DC, in 1913. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-70382

Suffragists staged a tableau at the US Treasury Department steps during their monumental parade in Washington, DC, in 1913. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-70382

The Woman’s Journal printed a headline about the “disgraceful” crowd at the event.

The Woman’s Journal printed a headline about the “disgraceful” crowd at the event.

Library of Congress LC-DIG-ppmsca-02970

SUFFRAGISTS wrote and performed in plays to bring their ideas to large audiences. Often their costumes followed patriotic themes that recalled ancient Greece, the cradle of democracy. Suffragists, like the ancient Greeks, dressed up in white to portray Lady Liberty, Columbia, peace, and justice.

Greek men crowned their heads with laurel leaves when they won sports events. Greek women wore their hair in fanciful styles with twists and braids and often with hair decorations as well. Check out the examples at www.fashion-era.com.

With a few things you have at home or will easily find at a craft store, you can costume yourself like an ancient Greek. Wrap your head in glory!

You’ll Need

To make your laurel wreath, use the marker to trace the leaf pattern on this page onto a piece of paper and cut it out. Then transfer the leaf pattern to a piece of cardboard and cut the leaves out.

Working on a covered surface, glue the leaves to the headband. Follow the example and overlap them as you work your way around. When you are pleased with the effect, set the wreath aside to dry.

Spray paint the wreath and sandals or flip-flops. Follow the directions on the spray can, and be sure to spray outside in an open area with lots of fresh air.

Are you ready to dress in your costume? Put on the white T-shirt. To make your toga, start by folding a sheet in half lengthwise, as shown. Place one folded corner under your arm and wrap the sheet around you once. Fasten the sheet snugly with a safety pin. Continue to wrap the sheet around you until you have about 4 feet left. Drape this end across your chest and over your shoulder. Use more pins to fasten the sheet to your shirt. Now arrange the folds in your toga.

Slip into your footwear and put your laurel wreath on your head. Who are you? Peace? Columbia? Justice? Liberty? No matter whom you portray, you are standing up for suffrage!

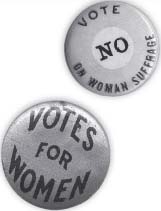

Not only men opposed women’s suffrage. Plenty of women stood strong against the idea, and they organized committees in Eastern cities, though their efforts did not catch on with women who lived west of Ohio. The Association Opposed to Suffrage for Women, the “Antis,” argued that most women did not want the vote and that their place was at home.

Women like Josephine Dodge of New York quietly recruited members at parlor meetings. Always known as “Mrs. Arthur Dodge,” she had pioneered day care for working mothers. Dodge worried that winning the vote would lead women into immoral ways.

Carrie Catt was pleased to hear that sometimes these tea parties backfired. At one of these antisuffrage gatherings, a guest became “so indignant at what she heard” she wrote a check for $10,000 for the suffragists. It was the biggest donation any living person had ever given to win votes for women. (Today that gift would be worth more than $230,000.)

Nationwide efforts to ban alcoholic drinks were as strong as ever. As always, the liquor industry worked against suffrage as well. Catt suspected that the Antis quietly worked with liquor sellers. Suffragists “believed that a trail led from the women’s organization into the liquor camp and that it was traveled by the men the women Antis employed.”

Did the man who sent this postcard in 1914 agree with its message?

Did the man who sent this postcard in 1914 agree with its message?

A pair of campaign buttons shows both sides of the suffrage movement.

A pair of campaign buttons shows both sides of the suffrage movement.

The Antis did their work state by state, sending a man and a woman to work together. The woman met with otherwomen to gain their support against suffrage. The Anti men met with other men, including liquor dealers and their political buddies.

The well-organized Antis made the front pages of newspapers everywhere. There was plenty of room for disagreement on this burning issue in American life.

THE SUFFRAGE movement pained Woodrow Wilson. When he entered the White House, the new president did not take suffragists seriously. Even in the second decade of the new, modern century, most American men still did not think women needed to vote. A young suffragist, Doris Stevens, wrote about a meeting between Wilson and suffragists.

Dr. Anna Howard Shaw led the interview. In reply to her eloquent appeal for his assistance, the President said in part: “I am merely the spokesman of my party…. I am not at liberty to urge upon Congress in messages, policies which have not had the … consideration of those for whom I am spokesman….”

[Shaw’s] clear, deep, resonant voice… was in sharp contrast to the halting, timid, little, and technical answer of the President.… Dr. Shaw had dramatically asked, “Mr. President, if you cannot speak for us and your party will not, who then, pray, is there to speak for us?”

“You seem very well able to speak for yourselves, ladies,” he said with a broad smile.

“We mean, Mr. President, who will speak for us with authority?” came back the hot retort from Dr. Shaw.

The President made no reply.

Moderate suffragists like Carrie Catt and Anna Shaw annoyed Woodrow Wilson, and militants like Alice Paul and Lucy Burns outraged him. In January 1917, suffragists appeared on the sidewalk along the iron fence outside the White House. They carried colorful banners and picket signs with messages to the president. The demonstrators broke no law; the Bill of Rights guaranteed them the freedom to assemble.

But suffragists were only one problem the president faced. In the summer of 1914, a terrorist shot and killed an Austrian archduke who was visiting Serbia. The huge Austro-Hungarian Empire declared war on the tiny Balkan nation.

President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany in April 1917.

President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany in April 1917.

Library of Congress LC-USZC4-10297

Dr. Anna Howard Shaw was sketched in pencil at a suffrage meeting.

Dr. Anna Howard Shaw was sketched in pencil at a suffrage meeting.

Europe’s governments were caught in a complex web of treaties and friendships. War became certain as European nations joined forces with their friends and allies. On one side were the Central Powers: Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy. On the other was the Triple Entente of France, Great Britain, and Russia. Most of Europe’s smaller countries lined up behind one power or the other.

When the House of Representatives voted to approve the 19th Amendment during a vote in 1918, one woman stood up to say “Yea.” She was Jeannette Rankin, a proud Montana suffragist and America’s first congresswoman, elected in 1916. Rankin made her name in her home state by getting permission to address the Montana legislature on the subject of suffrage. A few years later, voters thanked her for her efforts by sending her to Washington.

Raised on a ranch, Rankin spent her life working for the welfare of others, first as a social worker, then as a suffragist, and finally as a peace activist. She was elected to Congress twice as the nation went to war, the first time before World War I, the second time before World War II. “As a woman, I can’t go to war,” she said, “and I refuse to send anyone else.”

As a pacifist, a person who opposes war of any kind, Rankin’s views won her few friends in government or back home. Both times, she lost reelection to Congress.

All her life, Rankin pushed for women’s rights and peace between nations. “You can no more win a war than win an earthquake,” she declared. Rankin also had bitter words for women who approved of war. She called them “worms” who let their sons go off to war “because they’re afraid their husbands will lose their jobs in industry if they protest.”

Jeannette Rankin never feared speaking her mind. She continued to work for world peace until her death in 1973 at age 92.

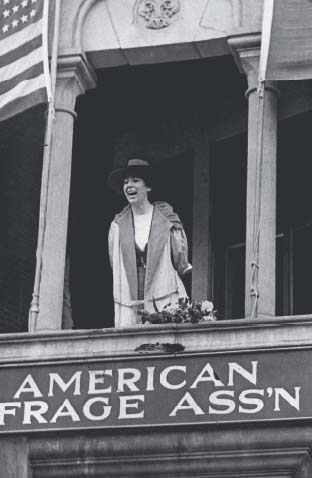

America’s first congresswoman, Jeannette Rankin, posed on the balcony of the National Woman’s Party headquarters.

America’s first congresswoman, Jeannette Rankin, posed on the balcony of the National Woman’s Party headquarters.

Library of Congress mnwp 156007

Over the next four years, this Great War, later named World War I, led to the deaths of 8.5 million soldiers and decimated a generation of young men.

The United States held to a neutral stance, but German submarines began a campaign to sink ships on the Atlantic Ocean. Some carried American passengers. Over the months, the German threat appeared to grow ever greater. By early 1917, war seemed inevitable, and the United States declared war on Germany in April. For the president, the suffragists, and the United States, life would never be the same.

By the summer of 1918, more than 1 million US soldiers had sailed to France to fight Germany. “Our boys” was the loving term applied to the young men who came from all 48 states to fight against the evil Kaiser Bill, as the press nicknamed Germany’s leader, Kaiser Wilhelm II.

With the men gone to war, America’s women stepped in to do their work. “Every muscle, every brain, must be mobilized if the national aim is to be achieved,” wrote Harriot Stanton Blatch. She was talking about American women.

With brains and muscles, American women manufactured ammunition, built airplanes and railroad cars, and hauled heavy blocks of ice in horse-drawn wagons to supply their neighbors’ iceboxes. Others dressed in the sober gray uniforms of the American Red Cross to deliver telegrams to the families of soldiers who had been injured or killed. Some women went to war in France to serve as nurses in battlefield hospitals or run canteens where soldiers could get a doughnut and a cup of coffee.

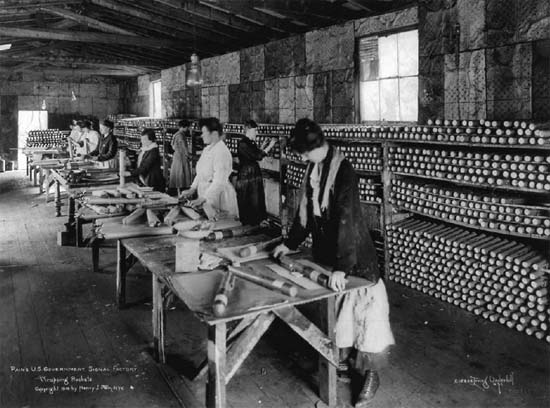

Women worked in munitions plants manufacturing rockets during World War I. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-53195

Women worked in munitions plants manufacturing rockets during World War I. Library of Congress LC-USZ62-53195

OLD photos of suffragists show them marching with large wire banners that looked somewhat like kites. What’s on your mind? Design a banner to broadcast your ideas. It’s easy using a coat hanger and some cloth.

You’ll Need

Measure the width of the hanger. Using this measurement, trace a large rectangle on the cloth by following the diagram below. Carefully cut out your rectangle and place your banner vertically so that the long sides run up and down.

Leave a 2-inch margin at the top. Use the ruler to trace light lines for your words. Then lightly write your message in pencil. You can write “Votes for Women” or think of another slogan to voice your thoughts.

Cover a large surface with newspaper. Place your banner over the newspaper.

On January 10,1917, suffragists gathered in front of the National Woman’s Party headquarters and prepared to picket—for the first time—in front of the White House.

On January 10,1917, suffragists gathered in front of the National Woman’s Party headquarters and prepared to picket—for the first time—in front of the White House.

Library of Congress mnwp.160026

Use the marker to trace each word. Work neatly and carefully.

Line up the fringe along the bottom of your banner. Trim off any extra. Apply glue along the back edge of the fringe. Place it along the bottom edge of the banner and lightly tap in place with your fingers. Let dry.

Now mount your banner on the hanger. Turn the banner upside down. Fold 1 inch of the top to the back and press it with your fingers. Open it back up and apply a thin strip of glue along the folded-back edge. Place the hanger along the fold. Now seal the edge with your fingers so that the glue holds securely. Let dry.

Fly your banner proudly. If you would like to make another patriotic banner, cut strips of red, white, and blue cloth. Assemble it in the same way. Instead of fringing it, tie the colored strips together in a loose knot.

Suffragists remembered the lessons learned long ago during the Civil War. The NAWSA women agreed to do war work, but this time they kept up their push for suffrage too. They did not let the terrible news coming from the battlefields of France silence them.

In people’s eyes, this Great War became the “war to save the world for democracy.” To Alice Paul and the National Woman’s Party, the war became a perfect example of what was wrong in American society. How could American soldiers die in a war for freedom when American women had no freedom to vote?

Alice Paul adjusted her tactics. The messages to President Wilson and the rest of the nation were about to change.

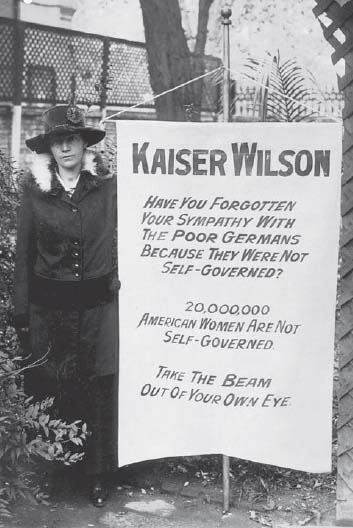

THE NWP grew bolder and louder. In January 1917, protesters carrying picket signs became a regular sight at the White House. In June, the police arrested a few marchers on charges of blocking the sidewalk. As 1917 dragged on, the protests grew more heated. When picketers showed up at the fence outside the White House, their signs screamed with passion. “Mr. President,” one read, “how long will women wait for liberty?” Another went further. Harsh words drawn from a Bible passage ripped the president, comparing him to Germany’s leader. “Kaiser Wilson … 20,000,000 American women are not self-governed. Take the beam out of your own eye.”

Summer melted into fall, and still suffragists showed up outside the White House as the scene got hotter and more women were arrested. By now, judges had sentenced 97 of the women to prison.

Alice Paul was arrested on October 20 and was sentenced with other protesters to jail. Their jailers treated them with contempt. The jail windows stayed locked until the angry women broke one to get some fresh air. At mealtime, the women tried to choke down disgusting meals of raw salt pork, bread, and molasses.

Still, they tried to rebel. Alice Paul and Rose Winslow, a factory worker, declared themselves to be political prisoners, ones who had been thrown in jail because they had protested a law. Their claim surprised and annoyed their jailers—political prisoners didn’t show up in American jails.

Weak from not eating, Paul and Winslow were carried into a prison hospital. Together they decided to take drastic action. On November 5, they went on a hunger strike and refused to eat at all. Prison doctors did all they could to prove that Paul was a mental patient. They locked her away in the room, boarded up one of its windows, and allowed no one, including lawyers, to see her.

A woman displayed a picket sign outside the White House in 1917. The sign referred to the president as “Kaiser Wilson.” Library of Congress mnwp 160030

A woman displayed a picket sign outside the White House in 1917. The sign referred to the president as “Kaiser Wilson.” Library of Congress mnwp 160030

Paul insisted that she was a political prisoner and nothing more. Then the forcible feeding began. Winslow and Paul underwent the torture three times a day. Rose Winslow wrote notes on tiny pieces of paper that were smuggled outside.

Alice Paul is in the psychopathic ward. She dreaded forcible feeding frightfully, and I hate to think how she must be feeling. I had a nervous time of it, gasping a long time afterward, and my stomach rejecting during the process.… The poor soul who fed me got liberally besprinkled [sprayed with vomit] during the process. I heard myself making the most hideous sounds.… One feels so forsaken when [one] lies prone and people shove a pipe down one’s stomach.

As PAUL, Winslow, and others fought their battles in the Washington jail, 41 more women showed up outside the White House to protest with gold-lettered banners and flags in the NWP’s colors—purple, white, and gold. Several times they were arrested and released, until finally a judge sentenced them to prison as well. But this time the women were taken to Virginia to a notorious workhouse. They were not prepared for what happened when they arrived at the prison on November 14, 1917.

Barely able to walk, suffragist Dora Lewis was released from prison after living through a “Night of Terror.” Library of Congress mnwp 160039

Barely able to walk, suffragist Dora Lewis was released from prison after living through a “Night of Terror.” Library of Congress mnwp 160039

The jail’s superintendent, backed by a group of guards who had not dressed in their uniforms, seized the women and dragged them to their cells. Lucy Burns, her arms manacled to a bar high above her head, hung there all night, barely able to stand. Dorothy Day, later a well-known Catholic social activist, was thrown down twice over the arm of an iron bench. The “elderly Mrs. Lawrence [Dora] Lewis … was literally thrown in. Her head struck the iron bed. We thought she was dead,” Doris Stevens, also a prisoner, recalled. Another woman had a heart attack, but the guards paid no attention.

The suffragists followed Alice Paul’s example. They declared themselves political prisoners and went on a hunger strike. Lucy Burns and Dora Lewis were forcibly fed. Finally, a sympathetic marine who had seen the violence reported the news to Washington. It took days, but friends of the women went to court to win their freedom.

The jailers stalled. They didn’t want anyone to view the prisoners until the women had recovered. When they did appear at court, the women, “haggard, red-eyed, sick,” limped to their seats. Others were so weak that they had to be stretched out on the wooden benches in the courtroom. Some “bore the marks of the attack.”

The judge ordered the women to be moved back to the Washington jail. There they kept up their hunger strike. They would not give up. Then suddenly, they were released on November 28.

When Americans read the news of suffragists suffering the Night of Terror and forcible feedings, they felt sick, too. The jailers’ harsh treatment transformed the suffragists into heroes. Powerful senators and congressmen launched investigations about the brutal attacks. At long last, the issue of votes for women was on the front pages of newspapers everywhere, and Americans could no longer look the other way.

Neither could President Wilson, who found it a relief to deal with the calm, much older Carrie Catt and NAWSA. Members of NAWSA had made no official comments about Alice Paul and her crew. Yet it was plain that the militant suffragists had hit their mark.

Wilson, who respected Catt as much he disrespected Paul, decided to support a constitutional amendment to give women the vote. The weary president needed both women and men to back him as he led the United States during wartime.

On January 10, 1918, Congress met to vote on the 19th Amendment to the Constitution. No one could be sure that the amendment would pass in the US House of Representatives. Every vote counted, and several representatives turned out in support of women’s suffrage.

Lucy Burns, dressed in prison garb, sat outside her cell. Library of Congress mnwp 274009

Lucy Burns, dressed in prison garb, sat outside her cell. Library of Congress mnwp 274009

One congressman, his face showing pain from a broken shoulder, arrived to vote yes. Two others left their hospital beds to do the same. As suffragists watched and waited, Congressman Frederick Hicks arrived from New York. His wife was dying, but he knew she wanted him to vote yes.

There were 410 members in the House of Representatives. A two-to-one majority was needed, and as the congressmen voiced their yeses and nos, the suffragists kept count. When they heard the 274th yes, they rejoiced. In the halls of Congress, happy women sang the old hymn “Praise God from Whom All Blessings Flow.”

The congressman from New York went home to bury his wife.

IN NOVEMBER 1918, World War I came to an end, and Americans celebrated their victory against Germany. The women of Great Britain, Canada, and Germany, too, were given the right to vote. But with the vote for the 19th Amendment held up in the US Senate, militant suffragists kept up their protests.

It took months to persuade a handful of Senate holdouts that women deserved the vote. The suffragists appealed to the president to act. Again they demonstrated, were arrested and jailed, and went on hunger strikes.

In February 1919, yet another band of marchers burned a small picture of President Wilson outside the White House and were sent to prison. Paul won even more publicity by sending the Prison Special, a train loaded with suffragist prisoners, on a cross-country tour. Among them was Louisine Havemeyer, well into her 60s, who had managed to get herself arrested.

As the train steamed from state to state, curious Americans gathered at the stations to hear what the former prisoners had to say. Not all approved of Alice Paul’s tactics, but many admired these women who had gone to jail for their beliefs.

By now, both the Republican and Democratic parties backed suffrage. On May 19, 1919, President Wilson called a special session of Congress. Again, the US House of Representatives voted to pass the 19th Amendment. On June 4, it went to the US Senate. Four Southern senators tried to stop the amendment. They felt sure that giving votes to women would make it easier for African Americans to demand their own voting rights in the segregated South.

Before she became a suffragist, Louisine Elder Havemeyer had already made her name in America’s art world. As a young girl in the 1870s, she lived in Paris with her mother and sister, where she met Mary Cassatt, who was to become the century’s most famous woman painter. Over the years, Cassatt introduced Havemeyer to French painters like Edgar Degas and Claude Monet, whose modern works had shaken up Paris’s stodgy art world.

Louisine Elder married O. H. “Harry” Havemeyer, a New Yorker who made a fortune in the sugar industry. Havemeyer, an eager collector of art from Japan and China, enthusiastically backed his wife’s own art collecting. Over the years, they gathered a huge collection of paintings and sculpture worth millions of dollars. (Today much of their collection appears in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Havemeyer learned to support women’s rights while she was growing up. Susan Anthony, Lucretia Mott, and Elizabeth Stanton were household names. When she married, Louisine Havemeyer also had her husband’s blessing to speak out as well as expand her mind.

After Harry Havemeyer died in 1907, Havemeyer devoted her energy to women’s suffrage. She wrote about her experiences for Scribner’s Magazine. Havemeyer was not afraid to criticize President Wilson, “to whom the thought of mobilized womanpower was as a red rag to an infuriated bull.” Her article, “Memories of a Militant” (a very rich, influential militant), made readers think.

Louisine Havemeyer, once jailed for protesting at the White House, posed with a policeman during her train tour on the Prison Special. Library of Congress mnwp 160058

Louisine Havemeyer, once jailed for protesting at the White House, posed with a policeman during her train tour on the Prison Special. Library of Congress mnwp 160058

When she went to jail, members of Havemeyer’s family telegraphed angry messages to her. The family matriarch had let them down. When she visited her daughter’s home, her son-in-law refused to welcome her, and she had to sit in the car.

Havemeyer traveled on the Prison Special for 29 days, shaking hands, raising money, and claiming votes for women across America. When the train pulled into the station in New York, she happily noted that the suffragists had won many friends and good publicity. With the typewriters “still clicking and the coins still chinking,” she left the train in a hurry to make one more speech—at New York’s famed Carnegie Hall.

Nonetheless, 66 senators voted “aye.” President Wilson was in France at a peace conference. With a gold pen, vice president Thomas Marshall signed the 19th Amendment.

At long last, the men who held power in the nation’s capital had done the right thing. The 19th Amendment was on its way to the states. Three-fourths of the 48 state legislatures had to ratify—vote to approve—the 19th Amendment. For suffragists, there was much more to accomplish.

The 19th Amendment. National Archives

The 19th Amendment. National Archives