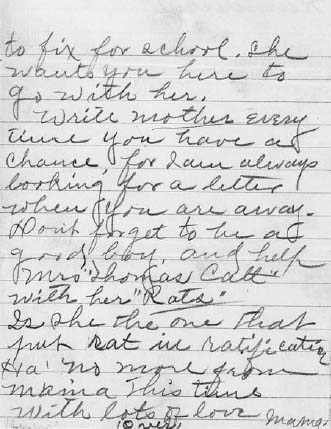

IN THE summer of 1920, a Tennessee mother wrote a letter to her 24-year-old son, whose name was Harry Burn. At age 24, he was the youngest member of the all-male Tennessee House of Representatives. Mrs. Febb Burn had followed the newspapers all summer. Sprinkled in with all the news from home were her feelings about votes for women and a reminder:

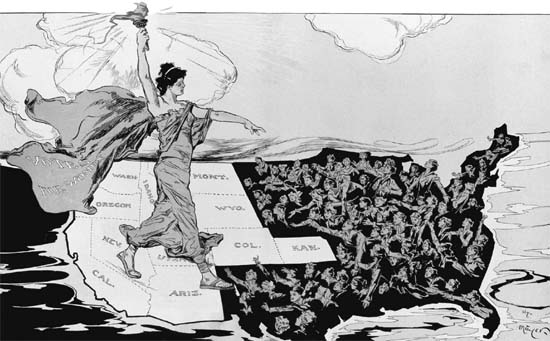

Dear Son…

Hurrah and vote for Suffrage and don’t keep them in doubt…. I noticed Chandler’s [a Tennessee man’s] speech. It was very bitter I’ve been watching to see how you stood, but have not seen anything yet….

Don’t forget to be a good boy and help Mrs. “Thomas Catt” with her “Rats.” Is she the one that put rat in ratification… Ha!…

With lots of love

Mama

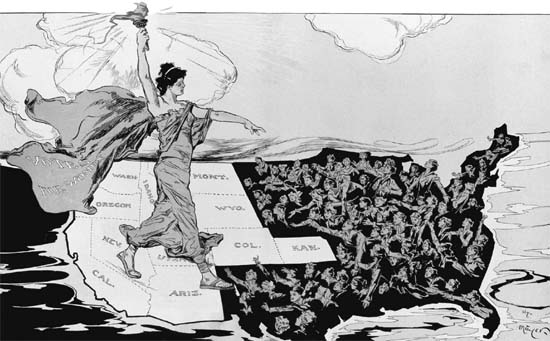

By 1915, all of the Western states except New Mexico had granted women the right to vote in state and local elections. Library of Congress LC-USZC2-1206

By 1915, all of the Western states except New Mexico had granted women the right to vote in state and local elections. Library of Congress LC-USZC2-1206

THERE WERE 48 states in the United States of America, so the magic number for women’s suffrage was 36. Thirty-six state legislatures had to vote yes on the 19th Amendment. Only then would it become a part of the US Constitution. Only then would American women everywhere have the right to vote.

Suffragists rolled up their sleeves and resumed their campaigning. They were leaving nothing to chance. From the headquarters of both NAWSA and the NWP, suffragists fanned out across the country.

At first, the yeses came quickly. In one month, 11 state legislatures voted for ratification. Within six months, another 11 came onboard. State by state, legislators voiced their approval for women’s suffrage. Washington was the 35th state to ratify the amendment.

The summer of 1920 unfolded. Suffragists studied the numbers and considered the rumors that poured in from states that had not voted. The situation in Tennessee looked hopeful. A “yes” from both houses of the Tennessee legislature would push ratification over the top.

Page six of Febb Burn’s letter to her son Harry. Harry T. Burn Papers, McClung Historical Collection

Page six of Febb Burn’s letter to her son Harry. Harry T. Burn Papers, McClung Historical Collection

When Harry Burn opened this envelope, he discovered his mother’s views on votes for women. Harry T. Burn Papers, McClung Historical Collection

When Harry Burn opened this envelope, he discovered his mother’s views on votes for women. Harry T. Burn Papers, McClung Historical Collection

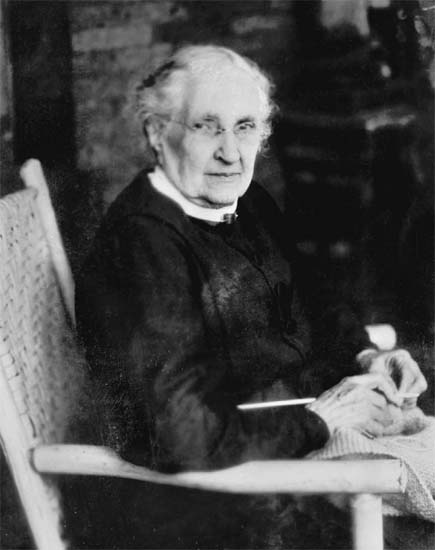

Febb Burn.

Febb Burn.

Harry T. Burn Papers, McClung Historical Collection

Harry Burn’s vote made women’s suffrage the law of the land. Harry T. Burn Papers, McClung Historical Collection

Harry Burn’s vote made women’s suffrage the law of the land. Harry T. Burn Papers, McClung Historical Collection

Carrie Catt packed her bags and took the train to Nashville, expecting to stay a few days to pitch in and help win votes. As things turned out, she spent over a month in the Tennessee heat and humidity.

At the NWP building in Washington, Alice Paul was stitching a banner. Every time a state voted to ratify the 19th Amendment, she cut out a star and stitched it to the long piece of cloth. By August 15, 1920, Paul had cut and stitched 35 stars onto the banner. She set her needle and thread aside, waiting like everyone else for the Tennessee legislature to change American history forever.

Ratification in Tennessee moved as slowly as the sun on those long summer days. Antisuffragists poured into the state from all over the country, hoping to make their last stand and to block votes for women. Legislators, suffragists, and Antis packed into the Hermitage Hotel in Nashville. It became a “war of the roses.” Suffragists and their male backers wore yellow roses, and the Antis sported red ones.

Mysterious men showed up to work quietly behind the scenes. They paid bribes to any Tennessee legislators willing to take money and vote no on suffrage. Upstairs in rooms at the Hermitage Hotel, liquor dealers held parties for the legislators, hoping to win their votes against suffrage. Tennessee bourbon and moonshine whiskey—both outlawed— flowed into their guests’ glasses.

All around, the dirty dogs of politics showed their teeth. A notable representative who had pledged his support for suffrage changed his mind. Then, without warning, more legislators backed off.

The suffragists did not have to worry about the Tennessee Senate, which quickly voted its approval by an overwhelming vote of 25 to 4. Then it came time for the Tennessee House to vote. There were 96 representatives. Forty-nine votes were needed for ratification to pass. Suffragists waited nervously.

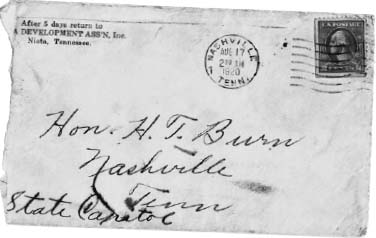

When Harry Burn stood up to voice his vote on ratification, he wore the red rose of the Antis pinned to his lapel. The men in his district didn’t support votes for women. But in his pocket was the letter from his mother. Burn had taken her words to heart. He voted “aye.”

Harry Burn’s vote put the “rat” in ratification of the 19th Amendment, giving women the right the vote throughout the United States of America. In the exact words that Susan B. Anthony had written in 1878, the 19th Amendment became the law of the land: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

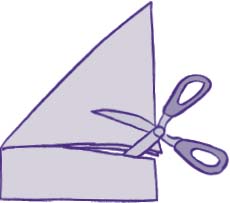

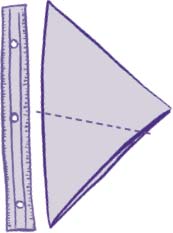

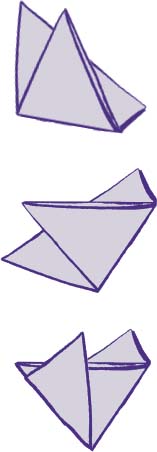

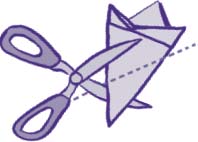

ACCORDING to legend, George Washington and two other Revolutionary leaders asked Betsy Ross to stitch the first American flag with five-pointed stars. She folded up a piece of paper and, with just one snip of her scissors, cut a perfect star.

We don’t know whether Alice Paul used the same technique when she cut out the stars for her suffrage banner. However, you can create five-pointed stars with one cut, just like Betsy Ross did.

You’ll Need

First practice using paper to cut five-pointed stars. Trim a piece of paper into a square by matching the top edge to one side and trimming away the excess with scissors.

Measure halfway down the length of the fold and mark that spot with the pencil. Now measure 2¼ inches down from the upper right-hand corner of the paper and place a mark there as well. Draw a line to join both marks and fold along the line.

Place the paper facing you as shown. Fold along the dotted line, bringing the bottom point up and over as shown.

Place the paper on your work surface as shown. You now have a “kite” shape facing you.

It’s time for one last fold. Bring the two edges together and fold as shown.

Do you see the triangle? Measure and mark a point 3 inches from the upper left-hand point. Now draw a line from the mark to the opposite corner.

Now it’s time to make just one cut along the line. Pick up your scissors and cut!

Pull the extra bits of paper away and unfold your star. How do you think Betsy Ross learned to cut a star this way? (There are easier methods used in origami, which is the Japanese art of paper folding. You can look them up on the Internet.)

Now that you can cut out such cool stars, how can you use them? Look around the house for other kinds of paper to fold and cut your creations.

On Election Day in November 1920, women took their place in line along with men at polls across the nation to vote for a new president. However, one elderly woman long past her 90th birthday was too sick to get to her polling place. She was Charlotte Woodward Pierce, the frustrated glove maker who had gone with her friends to the Seneca Falls women’s rights convention in 1848. Pierce was the only person at the meeting who lived long enough to see women win the vote. In the end, she died before she could ever cast a ballot.

SURE THAT their work was complete, the National American Woman Suffrage Association disbanded. Carrie Chapman Catt went on to serve as the first president of the League of Women Voters.

Alice Paul added the final star to her banner, but she believed that a woman’s work was never done. Women had the vote, and now there was more to accomplish. Always the realist, Paul saw that women lacked true economic power.

The history of the 1900s proved that she was correct. For most of the century, women were paid less than men for working the same jobs. Most top jobs stayed closed to them. Women were welcome to work as secretaries or clerks, but they seldom sat in the boss’s corner office.

Charlotte Woodward Pierce waited all her life for the right to vote. Library of Congress LC-F81-11964

Charlotte Woodward Pierce waited all her life for the right to vote. Library of Congress LC-F81-11964

In trade jobs where men worked with their hands, women weren’t welcome either. Except when men went overseas to fight during World War II, women could not hold jobs building cars on assembly lines or work as plumbers, welders, electricians, or mechanics.

Alice Paul unfurled her banner to celebrate the hard-won battle for women’s suffrage. Library of Congress mnwp 160068

Alice Paul unfurled her banner to celebrate the hard-won battle for women’s suffrage. Library of Congress mnwp 160068

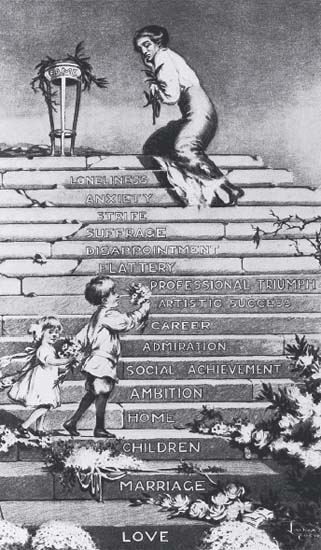

Cartoons often are filled with powerful symbols. The cartoon below about women’s suffrage appeared in 1918.

Library of Congress LC-DIG-ppmsca-02940

Library of Congress LC-DIG-ppmsca-02940

The artist who drew it hoped to get a reaction from his readers.

What’s your reaction? Study the cartoon carefully. What do you think the cartoonist thought about suffragists? Did he support or oppose votes for women?

To help you judge the cartoon, think about what images the artist chose. How did he draw them? Where did he place them? What do the stair steps symbolize? How do the words he chose have meaning?

Most important, how do you feel when you look at this cartoon? Are you amused? Confused? Annoyed? What kinds of emotions rise in you? Are you surprised at your reaction?

A postage stamp celebrated the 50th anniversary of women’s suffrage in 1970. United States Post Office

A postage stamp celebrated the 50th anniversary of women’s suffrage in 1970. United States Post Office

When Americans began to travel more frequently on airplanes in the 1960s, women served as flight attendants (then called “stewardesses”), but only men could hold the high-status job of pilot. Some women worked as lawyers, doctors, engineers, or scientists. A handful became astronauts. Not until the end of the 20th century did women begin to rise to top jobs in companies. To do so, businesswomen felt they had to break through an invisible “glass ceiling” of discrimination.

Some women served in Congress, but women didn’t begin to achieve true political power until late in the 1900s. In 1984, Geraldine Ferraro was nominated to run for vice president of the United States as a Democrat, and in 2008, the Republican Party also nominated a woman—Sarah Palin—as their candidate for vice president.

During that long presidential campaign of 2008, it appeared that a woman, Hillary Rodham Clinton, would win the Democratic Party nomination to run for president of the United States. However, she was defeated in primary elections by a male African American senator, Barack Obama, who surprised the nation by declaring his candidacy. He went on to become the nation’s first president of color.

Most Americans have forgotten the story of women’s struggle to win the vote. But Alice Paul never forgot, and she always looked forward to improve women’s lives. In 1923, Paul wrote an Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution. It said, “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

Paul believed that this amendment would give women the economic power they deserved in America’s workplaces. It took until 1972 for the amendment to pass through Congress. This “ERA” was sent to the states for ratification, but it had a deadline. As with the suffrage movement 100 years earlier, the ERA divided Americans. Only 35 state legislatures voted yes, and the amendment withered away after 1982. Paul died in 1977, never to see her amendment ratified.

Equal rights for women are not yet the law of the land in the United States.

A Tennessee cartoonist understood the history behind the 19th Amendment when he drew this image. Tennessee Historical Society

A Tennessee cartoonist understood the history behind the 19th Amendment when he drew this image. Tennessee Historical Society