The Berlin Philharmonic and the American Military

DURING THE FINAL DAYS OF THE THIRD REICH, conductor Leo Borchard huddled in a Charlottenburg cellar with several friends. The group had miraculously survived Hitler’s reign as opponents of the Nazi regime, yet the arrival of Russian troops brought other dangers. Once Soviet soldiers reached Borchard’s street, several Werwolf agents, fanatical Nazis determined to resurrect the Third Reich, fired on the invaders. The Russians frantically searched the block for the shooters, mistaking Borchard and his group first for Werwolf operatives, and then equally as fatally, for partisans. With candles blazing and four Soviet officers staring on in stony silence, Borchard tried to placate the soldiers by singing their national anthem; his partner, journalist Ruth Andreas-Friedrich, immediately realized, “He’s singing for our lives.”1 As he finished, the mood lightened as the soldiers clapped him on the back and shared their food, a small feast of bacon and sausage. Never before and never again would Borchard give such a command performance.

Fluent in Russian, Borchard soon made an impression on the Soviets, befriending General Nikolai Bersarin, commander of the occupying forces. Bersarin admired not only Borchard’s talent as a musician but also his work for Onkel Emil, a small communist resistance group that hid Jews during the Third Reich and provided them with falsified documents. Borchard was just the kind of comrade that the general needed to rebuild the city’s musical culture, and Bersarin quickly appointed him Generalmusikdirektor of the Berlin Philharmonic. With the Philharmonic’s principal conductor, Wilhelm Furtwängler, living in Swiss exile, Borchard was savvy enough to realize that Bersarin’s decision could mean the career opportunity of a lifetime.2

To the Russian occupiers, Borchard was uniquely qualified to play a leading role in the city’s reconstruction. Born to German parents in Moscow in 1899, he spent most of his childhood in St. Petersburg, moving to Berlin after the Russian Revolution. Eventually, he found work as an assistant conductor at the Kroll Opera, an institution funded by the Weimar government that encouraged modernist opera stagings. With Otto Klemperer as its music director, political turmoil meant the Kroll Opera would be a short-lived experiment, and it closed in 1931. Again looking for work, Borchard briefly served as a cultural ambassador for the Reichsmusikkammer (RMK) in occupied Greece. Occasionally, he even appeared as a guest conductor with the Berlin Philharmonic, leading a March 1943 concert of contemporary music by Gottfried von Einem, Werner Egk, and Zoltán Kodály.3

The Philharmonic had been the most celebrated ensemble under National Socialism, and the Soviet occupiers were content to allow the musicians to continue concertizing with little oversight. In early May, with the city now under Soviet control and the Americans’ arrival still two months away, Philharmonic musicians were uncertain about the ensemble’s fate. On May 13, only five days after Germany’s surrender, Borchard and forty Philharmonic members decided to rehearse at the Wilmersdorf home of clarinetist Ernst Fischer. In lieu of public transportation, they traveled on foot or by cycling through the ruins; double bassists pushed their instruments in wheelbarrows or in baby strollers. Among the first order of business was to assess the ensemble’s performing forces and material resources. Seventy of the orchestra’s 110 musicians fled Berlin in the final weeks of the war, and not all would return. Allied bombing had leveled the ensemble’s hall and destroyed most of the orchestra’s instruments and scores. To assist with the orchestra’s rehearsals, Bersarin granted them permission to practice at Wilmersdorf’s town hall, formerly the site of Wehrmacht administration offices.4

On May 26, the Philharmonic gave its first postwar concert at the Titania Palast movie theater in Steglitz. Tickets were handwritten and the ensemble was less than half of its regular size, yet the hall was packed with concertgoers who applauded wildly as Borchard reached the podium. The orchestra opened the program with Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture, a piece they had not played since 1935. (The orchestra still had Mendelssohn’s scores due to the efforts of trombonist Friedrich Quante, who managed to hide select works by Jewish composers in a location he refused to divulge.) Borchard also conducted Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 5 in A Major and Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony.5

Although Ruth Andreas-Friedrich wrote in her diary that the concert erased memories of “Nazis, the lost war and the occupation forces,”6 her claim of transcendence, while appealing within the zero hour framework, was perhaps a calculated exaggeration for the benefit of posterity. Another eyewitness was less generous about the event’s resonance, describing the terror and chaos that ensued when Soviet soldiers burst through the theater’s doors with their pistols brandished during the Mendelssohn Overture. When the Russian soldiers left during the final movement of the Tchaikovsky, the audience breathed a collective sigh of relief.7

The orchestra’s rubbled personnel and repertoire were the literal and metaphorical debris of postwar musical culture. US cultural and intelligence officers supervised the Philharmonic between 1945 and 1949, and during the ambitious denazification and reeducation process, Information Control Division (ICD) officers registered compromised musicians and promoted American music and musicians. Yet as Nicolas Nabokov admitted, in the “still smoldering heap of rubble called Berlin,”8 it was impossible to begin entirely anew in light of scarce material resources and personnel, as the occupiers began the arduous task of sorting through the rubble of musicians and conductors.

Rubbled Musicians and Conductors

In early July, when the Americans arrived in Berlin, they were unsure how to supervise the ensemble. The orchestra’s close relationship to the regime had sustained the Philharmonic financially, but compromised them politically, as its members had served as cultural ambassadors and civil servants. As the most celebrated orchestra under the Third Reich (Reichsorchester) and the highest paid, Joseph Goebbels excused the Philharmonic from military service because he considered concert tours in occupied countries just as vital as armed combat. Even in the waning months of the regime, these musicians were exempt from serving in the Volkssturm, the desperate Nazi militia composed of young boys and old men.9

The ensemble’s final concert under the Third Reich took place on April 16, 1945, in the Beethovensaal beside the ruins of their former home. (British phosphorous bombs destroyed the Philharmonic’s primary concert hall in January 1944.) The program included Strauss’s Death and Transfiguration, an apt choice for the encircled city; earlier that morning, Soviet troops had commenced their assault on the capital. To the audience wrapped in their overcoats, the concert must have had a macabre air of finality. Even as heavy shelling began on the city center, the ensemble continued to practice. On April 20, Hitler’s birthday, the Philharmonic rehearsed with conductor Leopold Ludwig, although the two concerts planned for April 21 and 22 were canceled due to heavy artillery fire from the Russian advance.10

The ensemble prepared for the city’s fall in various ways. Most, like Borchard, hid in cellars, although not without incident. In the chaotic weeks that followed, the musicians were completely at the mercy of the Soviet occupiers. Soldiers seized double bassist Erich Hartmann and placed him in a detention center along with hundreds of other German men, presumably to be deported east. He managed to escape by climbing over a wall at an opportune moment. Hartmann had no intention of returning to Russia anytime soon. Wounded on the Eastern Front in 1943, he was one of the few Philharmonic musicians to have served in the Wehrmacht. Other orchestra members faced time as conscripted laborers for the occupiers; oboist Helmut Schlövogt had to work at Sachsenhausen concentration camp for several days.11

But these musicians were the fortunate ones. Several artists were killed by Allied bombing, including violinists Hans Ahlgrimm and Alois Ederer, clarinetist Oskar Audilet, and timpanist Kurt Ulrich. Violinist Bernard Alt and double bassist Alfred Krueger committed suicide along with their families before the surrender.12 Violist Curt Christkaus volunteered for the Volkssturm, only to drown in the Oder River while retreating from the advancing Russians. Harpist Rolf Naumann and oboist Willi Lenz were murdered for their bicycles as they fled west. Soviet soldiers took trumpeter Anton Schuldes into custody during the Battle of Berlin, and he was never seen again. Yet between war and peace, the orchestra kept practicing. One British officer recalled a Philharmonic rehearsal at the Theater des Westens on Kantstraße where Borchard conducted “a hundred odd men, poorly dressed by normal standards,” who played “a movement of a Beethoven Symphony amid the chaos and the ruins of that shattered street.”13

The ensemble concertized under Soviet jurisdiction until the Americans arrived in early July. The Titania Palast movie theater, the Philharmonic’s primary venue, was located in the American sector. The transition was not without its share of problems; at first, the 2nd Panzer Division requisitioned the Titania Palast for American troop entertainment, while US Special Services wanted to confiscate all the Philharmonic’s instruments that were stored in the basement. Borchard and music officer Henry Alter persuaded military authorities to reconsider, and they returned the instruments and granted the musicians access to the building. In acknowledgment of the Americans’ arrival, the orchestra gave two concerts exclusively for troops on July 8 and 9, featuring music by “Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdi” as posters announced.14

British and American cultural officers met with Borchard and the orchestra’s business managers on July 31 to discuss an eight-week plan for the Philharmonic. The officers decided that concerts would take place at least every weekend in either the American sector’s Titania Palast or the British sector’s Theater des Westens. Aside from these venues, the orchestra would perform in the American sector’s Zinnowald Saal in Zehlendorf, Cosmos-Kino in Tegel, Quick Theater in Neukölln, and the Soviet-controlled Rundfunkhaus, home of Radio Berlin.15 Music officer John Bitter understood that the orchestra was a valuable asset in the game of cultural diplomacy between the Allies. With Bitter and Alter’s help, the ensemble had amassed nearly one hundred musicians, leading Alter to conclude, “I really think that we saved the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra.”16 Although it was questionable that the Americans were solely responsible for the ensemble’s survival, they wasted no time in making adjustments to the orchestra’s roster.

Cultural officers aimed to purge Philharmonic musicians whose political backgrounds they deemed suspect. Grounds for removal were simple: if a musician had joined the party before 1935 or held a leadership position under the National Socialists, they were fired. All in all, there were far fewer party members in the Berlin Philharmonic than in comparable German-speaking ensembles. More than forty of the Vienna Philharmonic’s 117 musicians were former members of the Nazi Party, though these musicians faced even fewer consequences than their German counterparts. As Bitter complained in his report, “In contrast to the Berlin Philharmonic, the Vienna Philharmonic has always gotten away with murder in its prodigal use of Nazi members.”17

Of the seventeen former party members who played for the Berlin Philharmonic (fourteen full time and three part time), the Americans dismissed nine musicians, beginning with the orchestra’s business managers Joseph Stoehr and Lorenz Höber in December 1945. One aggravated music officer wrote that Höber “still can’t get it through his head that the Americans can get rid of him even though he was hired by the city of Berlin,”18 as the violist fought to remain employed by the Philharmonic. The ICD then fired seven other former party members: cellist Wolfram Kleber, horn players Georg Hedler and Adolph Handke, violinists Alfred Graupner and Hans Woywoth, double bassist Arno Burkhardt, and harpist Fritz Hartmann.19

Musicians who were dismissed on political grounds faced few real sanctions, however. They could relocate to other zones and sectors or, in certain cases, simply wait and resume their careers. Seven of the nine dismissed musicians found work in Berlin. The Russian-controlled Staatsoper hired Stoehr and Höber, the British-licensed Städtische Oper employed Kleber, and the American-run RIAS Symphony Orchestra recruited Hedler. Between 1946 and 1947, the Philharmonic even rehired Graupner, Burkhardt, and Handke as the ICD relaxed their denazification procedures.

During the denazification process, the orchestra struggled to maintain high performance standards as twenty instrumentalists left in search of better working conditions. Given the Philharmonic’s importance for their reorientation aims, ICD officers petitioned their military superiors to increase the musicians’ rations by four hundred calories per day. In his search for a scapegoat, Bitter also decided the ensemble’s managers were incompetent; “As devoted as I am to this group and their welfare, I feel a certain stagnation setting in because of the way the orchestra is run,”20 he wrote. To counteract what he believed were poor management decisions and to diversify the group’s repertoire, Bitter felt the Philharmonic needed a musical director. The orchestra flatly refused, voting against the idea sixty-five to one and pleading with the Americans to “help restore democratic self-representation, just as it was before 1933.”21 Bitter was forced to drop the idea once and for all.

Orchestral musicians, classified as “ordinary labor,” were but one component of the American denazification and reeducation plan. Finding suitable conductors, however, occupied the bulk of cultural officers’ time and efforts. In late July 1945, Rudolph Dunbar (fig. 2.1), a thirty-seven-year-old Guyanese American conductor and former war correspondent, paid Borchard a visit to discuss music. Over coffee in Borchard’s Charlottenburg apartment, they shared stories of the difficulties they experienced in establishing their careers. Borchard’s German citizenship meant that to the Allied occupiers, he was indelibly linked with the Nazi regime, while Dunbar encountered skepticism about his conducting abilities because of his skin color. As a parting gift, Borchard presented him with a volume of Bach cantatas, inviting him to conduct the Philharmonic sometime that fall. Andreas-Friedrich recorded the encounter in her diary, and although sympathetic to the struggles Dunbar faced, she also exoticized him: “Is it a victor, who is standing in front of us? In his elegantly styled American uniform, beautiful like a panther and passionately interested in Bach and Beethoven?”22

Figure 2.1. Conductor Rudolph Dunbar, September 1946. Carl Van Vechten photograph. ©Van Vechten Trust. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

On the evening of August 23, a British officer invited Borchard and Andreas-Friedrich to his villa in Grunewald, where they spent the night eating and drinking. Around midnight, Colonel Thomas Creighton, another British officer, offered to drive Borchard and Andreas-Friedrich back to Berlin given the strictly enforced curfew for all German civilians between 11:00 p.m. and 5:00 a.m. On the way home, Creighton and Borchard chatted amicably about music, and Andreas-Friedrich listened from the back seat. As Creighton approached an American checkpoint, he noticed a swinging lantern in the darkness. Assuming it was someone trying to hitch a ride, Creighton kept driving. The lantern had, in fact, been a signal to halt, and when the vehicle did not stop, the American officer on duty fired shots, fatally wounding Borchard. According to Andreas-Friedrich, Borchard’s final words were simply, “Next time, I’ll play Bach for you,”23 his utterance conveying the supreme irony of having survived the Third Reich only to be accidently shot by his liberators.

An untimely four days after his death, Newsweek ran an article about the conductor titled, “One Man Can Save German Music.” The piece made no mention of his shooting but instead cheerfully reported, “The problem of German music involves not only what to play—but who can be trusted to play it,” arguing that Borchard was “the only man, according to many critics, around whom the orchestra can hope to rebuild.”24 The entire article was a fabrication, doubly so now that the article’s protagonist was dead. It was not until 1955, ten years after Borchard’s shooting, that the American military government closed their official inquiry, declaring his death a Besatzungsschaden (occupation casualty) by concluding the British were at fault.25

Having accidentally killed the Philharmonic’s best hope for postwar reeducation and rehabilitation, the Americans were uncertain how best to proceed. At the next concert on August 25, Robert Heger directed the ensemble, and several leading Berlin artists gave speeches in Borchard’s honor, including Michael Bohnen, president of the Chamber of Artists and intendant of the British-controlled Städtische Oper, and violist Lorenz Höber, a Philharmonic manager who would soon be fired by the Americans. Instead of closing with Richard Strauss’s Don Juan as planned, the orchestra played the Funeral March from the Eroica, dedicating the movement to Borchard. Only three months earlier, the same piece had marked Hitler’s suicide.26

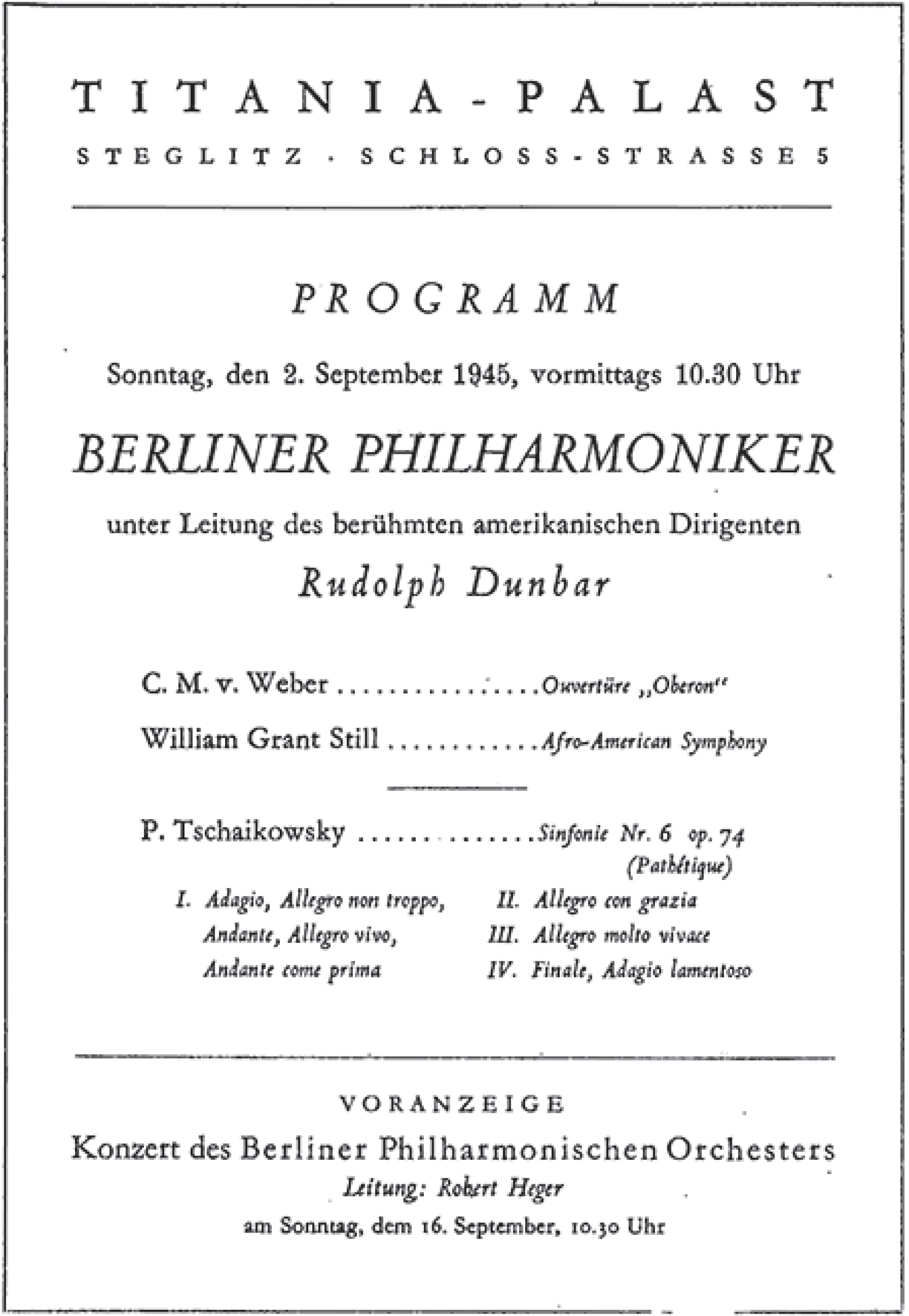

With Borchard’s unexpected death, Rudolph Dunbar got his chance to lead the Berlin Philharmonic sooner than he anticipated. On September 2, 1945, the orchestra, “under the direction of the famous American conductor” (fig. 2.2) performed Weber’s Oberon Overture, Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony, and William Grant Still’s Afro-American Symphony. Dunbar and Still were good friends, having played together in the Harlem Symphony Orchestra during the 1920s. The Berlin audience of two thousand applauded so vigorously that Dunbar returned to the stage five times for bows. As a goodwill gesture, he presented the Philharmonic with a Parisian contrabassoon, an instrument the ensemble lacked entirely as all of theirs had burned in Allied bombing raids. Dunbar repeated the performance the following day for five hundred Allied service members.27

The Allied Control Council, the governing body in Berlin comprised of representatives from the Soviet Union, United States, and United Kingdom, perceived Dunbar’s appearance as “a valuable step in wiping out racial prejudice,” as the New York Times reported, “Members of the orchestra, which has been known to ignore the conductor and play music its own way, agreed that Dunbar was a musical topnotcher.”28 Through Dunbar’s concerts, the Americans hoped to create the illusion that American views on racial equality were much more progressive than those of Germans.

As the first Guyanese American and member of the military to lead the Berlin Philharmonic, Dunbar sought the professional recognition that would come with conducting the ensemble. Yet his status as a second-class citizen within the very organization he represented meant that his appearance would not be taken seriously by the military or by much of the press. Time magazine concluded that military authorities pushed Dunbar to conduct because “their interest was more in teaching the Germans a lesson in racial tolerance than in Dunbar′s musicianship.”29 Furthermore, Germans civilians were well aware of the racial inequalities in the United States. Early Soviet propaganda emphasized the cruelty of the Jim Crow laws, and furthermore, segregation was on display in postwar Germany as black and white GIs still had separate regiments, barracks, and clubs. Military Governor Lucius Clay maintained throughout the postwar period that African American soldiers should be limited to marching in parades.30

Figure 2.2. Program for Rudolph Dunbar and the Berlin Philharmonic, September 1945. Courtesy of the Berlin Philharmonic Archive.

Even though many Americans of color may have experienced greater racial tolerance in postwar Germany, the country was still far from a utopia of acceptance. As Dunbar’s performance revealed, his appearance elicited a range of responses from the public, not all of which were positive. Philharmonic musicians were themselves uncertain of what to make of Dunbar’s appearance. An oboist in the orchestra could only register his shock by writing, “A Negro Officer Dünbar [sic] directs!”31 in his daily planner. One French newspaper even went so far as to note that Dunbar was “a conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic that Hitler certainly hadn’t expected.”32 After playing the Still symphony, one flutist confessed to a reporter, “Now at last I understand your American jazz,”33 reinforcing the pervading stereotype that music written by African American composers would be categorized as jazz, although Still’s genre-defying symphony was a hybrid of blues and classical influences. Despite Dunbar’s efforts and the support of the American military, the Philharmonic never again performed Still’s music.

Dunbar’s appearance was temporary, however, and the question remained who would become the ensemble’s permanent conductor. There were no ideal German forerunners for the position, and music officers were desperate to find a director with the necessary political qualifications and requisite experience. Yet the Americans soon banned or blacklisted nearly every major conductor who had remained in Germany during the Third Reich, including Hans Knappertsbusch (blacklisted for his Philharmonic propaganda tours), Leopold Ludwig (blacklisted as a former party member), Robert Heger (blacklisted for his frequent concertizing under the Third Reich), and Wilhelm Furtwängler (blacklisted and still awaiting denazification).34

There was no shortage of opinions concerning the Philharmonic’s new conductor. Colonel Creighton, Borchard’s driver the evening he was shot, believed the orchestra’s best hope was Fritz Busch. As a German émigré, Busch’s political and musical credentials were promising. After the Nazis fired him from the Dresden State Opera in 1933, he served as the first music director of the Glyndebourne Opera Festival between 1934 and 1939 before relocating to New York and conducting at the Metropolitan Opera. Creighton was so convinced of his plan that he wrote a mutual friend to inquire if Busch would be interested in the job, but the conductor would not end up returning to the ruins of Germany until 1951. With few feasible alternatives, when Philharmonic violinist Hermann Bethmann suggested his Romanian friend conduct a few performances, the Americans readily agreed. A composition student at the Hochschule für Musik, Sergiu Celibidache appeared to be the perfect fit for the ensemble: he had lived in Berlin since 1936 but had not been a member of the Nazi Party nor served in the Wehrmacht. Although Celibidache had relatively little conducting experience, he was young, energetic, and non-German. The occupiers were eager to dispel Nazi claims of German cultural superiority once and for all and agreed to give the conductor a chance.35

At the end of April 1945, Celibidache had turned down the chance to flee Berlin as it fell to the Russians. When a group of fellow Romanians offered him a place in their car heading west, he declined, reluctant to leave his compositions behind in Berlin while hoping “to experience everything with my own eyes.”36 Celibidache had a prescient sense that to stay in the city might mean better prospects for his career, foresight that would prove correct in only a few months. On August 29, the day of Borchard’s funeral, Celibidache led the Philharmonic for the first time. Brimming with energy and a volatile temper, the thirty-three-year-old musician was everything Furtwängler was not. After Celibidache’s first concert with the ensemble, oboist Helmut Schlövogt noted his surprise in his daily planner, writing “A Romanian directs!”37 It would be the first of more than four hundred performances the Philharmonic and Celibidache would give together.38

At the end of September, the city of Berlin assumed financial responsibility for the orchestra, contributing more than 120,000 Reichsmarks (RM) to rebuild the ensemble. After passing military clearance, Celibidache signed his name to the ensemble’s American-issued license along with Paul Schroer (second violin) and Ernst Fuhr (cello), the orchestra’s newly elected managers. The former Reichsorchester was now conducted by a Romanian, supervised by the Americans, and performing for Allied troops throughout Berlin. At a September performance exclusively for American soldiers, the Philharmonic opened with Wagner’s Tannhäuser Overture, played just before the nearly obligatory (if not clichéd) Mendelssohn selection, the Andante from the composer’s Italian Symphony.39

With the issue of who would become the ensemble’s primary conductor solved, American officers now used their connections with the Philharmonic to further their civilian careers. Nicolas Nabokov pushed for his own compositions to be played, and in May and June 1946, the orchestra acquiesced, performing his Parade. (As a point of comparison, between December 1945 and 1947, the ensemble played only three other American works.) The ensemble was hardly alone in performing the compositions of the occupation powers. As Berlin composer Max Butting noted in his memoir, “a high percentage of German interpreters preferred works by ‘their’ occupiers for opportunistic reasons.”40

John Bitter, as the Philharmonic’s appointed military supervisor, advised the group in many capacities, even though the lines between Bitter’s military duty and personal agenda began to blur. Although he wanted “to help rebuild the good Germany; that of Beethoven, Schiller, Goethe, and Brahms,”41 Bitter primarily used his military connections to gain valuable conducting experience for his return to civilian life. Between 1945 and 1948, he led the Berlin Philharmonic some thirty times. For his first performance with the orchestra, given for Allied troops on December 10, 1945, he began with John Philip Sousa’s The Stars and Stripes Forever in a pointed rejoinder to the banned Horst Wessel Lied that had once opened the orchestra’s concerts. The performance included waltzes from Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier, Sibelius’s Second Symphony, Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet Overture, and the German premiere of Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings. In an attempt to help German audience members connect with Corporal Samuel Barber, the notes observed that aside from his musical commissions for the army, Barber’s tasks included building latrines in Texas.42 Henry Alter sat in the audience for Bitter’s first performance, surprised that “he actually was not bad,” although he did find Bitter rather pompous, “looming quite large in his uniform.”43 Another officer noticed that Bitter “was so nervous I was afraid he would fall off the conductor’s podium.”44

While the Berlin press was generally positive about Bitter’s abilities, reviews of his concerts focused more on the orchestra’s sound than on the conductor. The ICD still monitored all forms of mass media in their sector and zone, and reviewers were careful not to castigate a member of the military. Outside of the American zone, critics were more forthcoming. After a July 1947 appearance at the House of Soviet Culture, one writer complained that Bitter’s interpretation of Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings sounded like Mozart due to its lack of “fervor, fire, spirit and sentiment.”45 Aside from conducting the Philharmonic, Bitter also made guest appearances with the Staatskapelle Berlin and RIAS Symphony Orchestra, the resident ensemble of the city’s American-run radio station, as well as performing with the Dresden Philharmonic, Hamburg Philharmonic, Gürzenich Orchestra Cologne, and Staatskapelle Kassel. Bitter introduced these orchestras to several new works, including Bartók’s Third Piano Concerto and Shostakovich’s First Symphony in Hamburg, Ravel’s La Valse in Cologne, and Hindemith’s Cello Concerto in Kassel, a work the composer wrote in America.46

The troubling nature of Bitter’s work with German orchestras, particularly the Berlin Philharmonic, was not lost on cultural officer Eric Clarke, a former arts administrator for the Metropolitan Opera. Although Clarke complained to a superior, “As the Berlin music officer who has nursed the Philharmonic along, should he [Bitter] face it in any other capacity? . . . Is he not weakening our present stand against entertaining Germans?,”47 the military did nothing to stop the conductor. In contrast to Bitter’s free rein, British cultural officers were not permitted to appear alongside German musicians, as one edict made clear, “no Military Government official may take advantage of his position to participate in German cultural activities.”48

Philharmonic musicians were similarly skeptical of Bitter’s abilities, and as Erich Hartmann admitted, “We had to work with him because he had political influence, maybe even military authority. . . . It was certain that he admired our orchestra, although the feeling was not always mutual.”49 In 1948, Electrola offered Bitter a recording contract with the Philharmonic. Eager to accept the deal, Bitter wrote to Benno Frank, offering to donate his potential earnings to charity, just as he had done with all of his German conducting engagements to date. Despite Bitter’s gesture of goodwill, Frank felt the recording would be a blatant conflict of interest and refused to approve his request.50

Yet the subtext of American efforts to control who conducted the ensemble revolved around one question: Would the Philharmonic’s principal conductor, Wilhelm Furtwängler, return to Berlin? Since February 1945, he had lived in self-imposed Swiss exile near Geneva. Although Furtwängler had never joined the Nazi Party, he had led the orchestra at select propaganda events during the 1930s and 1940s, enjoying one of the most visible and prestigious conductorships during the Third Reich. Despite Furtwängler’s insistence that his music could be separated from politics, his postwar reputation was severely compromised, and in February 1946, ICD director Robert McClure announced Furtwängler’s blacklisting across all zones and sectors of Germany, claiming, “It is an indisputable fact that through his activities, Furtwängler was prominently identified with Nazi Germany.” McClure went on to allege, “By allowing himself to become a tool of the party, he lent an aura of respectability to the circle of men who are now on trial at Nuremberg for crimes against humanity,”51 conflating the Nazi political and German cultural spheres. The American occupiers intended to make an example of National Socialism’s most celebrated conductor through a highly publicized denazification process, though, as Time magazine reported, “Furtwängler himself is viewing the struggle from a secluded nook in the Swiss Alps.”52

Evidence the Americans presented against the conductor included his one-year vice presidency of the RMK. The conductor resigned in 1934 as a result of his role in the Hindemith affair, a scandal caused by his support of the composer’s Mathis der Maler despite National Socialist opposition to the opera. Aside from Furtwängler’s activities within Nazi Germany, the Americans claimed the conductor had also participated in propaganda tours throughout occupied Europe, an allegation he denied. Occupied music, for Furtwängler, was going too far, as “I did not want to come in the wake of tanks into the countries.”53 Although it was Hans Knappertsbusch who led most of Philharmonic’s propaganda tours, Furtwängler had performed in the Czech Republic and in Denmark while both countries were occupied.

Furtwängler’s denazification continued for nearly two years as American authorities vacillated between wanting to punish National Socialism’s most decorated conductor while retaining the possibility of his services in the American sector. Meanwhile, the Soviets openly campaigned for Furtwängler’s rehabilitation, tempting him with offers to conduct at the Staatsoper to bypass American clearance. The Russians were more than willing to overlook Furtwängler’s recent past for a chance to have him working in their sector. But the conductor remained steadfast; he wanted to be reinstated by the Americans in order to direct the Philharmonic. He knew it would be a symbolic victory if he could resume his former post rather than accepting the Soviets’ offer. So he decided to wait.54

The conductor’s trial took place in two installments on December 11 and 17, 1946, led by intelligence officer Alex Vogel, and as Bitter reported, “Furtwängler will be permitted the use of a lawyer, but for advice only. He must do all the talking himself.”55 Witnesses included past and present members of the Philharmonic who used the opportunity either to laud Furtwängler’s courage or to wage a character assassination. Testifying in his closing remarks that he stayed in Berlin to help German music through the crisis of National Socialism, Furtwängler repeated the clichéd admonition, “No one, who was not in Germany at that time, could judge how it really looked here.”56 But the Americans’ task was to judge Furtwängler, not his working conditions during the Third Reich. After four months of deliberation, on April 29, 1947, the American military government classified the conductor as a Mitläufer (follower) and placed him in category IV, permitting him to resume his leadership role with the Philharmonic.57 As music officer Henry Alter later admitted of both Furtwängler’s and Herbert von Karajan’s denazification, to bar them from making music “would be punishing oneself.”58

Although Furtwängler believed German music was a form resistance to the Nazis, between 1939 and 1945 it was also the sound of occupation, domination, and subjugation. Even if he found the Nazis’ cultural politics distasteful, the regime still granted him a platform on which he could conduct in front of packed concert halls. Ultimately, Furtwängler’s crime was not that he was Nazi but that he failed to recognize the dangerously politicized role that music had taken on during the Third Reich. In his audiences sat party officials, civilians, and even forced laborers.59 By continuing to conduct beneath the swastika during the Third Reich, Furtwängler could not escape its presence in the postwar period either.

Ruins of Repertoire: The Act of Ruined Listening

The shattering of a collective listening experience began well before the fall of the Third Reich. A photograph of concertgoers taken during winter 1944, a year before the war’s end, reveals the pride of place that music held in Berlin. The small group trudges through the winter day, some with umbrellas, their heads bent down to avoid what was presumably a chilling wind. Dark hats and threadbare coats made a stark contrast against the falling snow. In the background, only ruins, as bourgeois society made their way home from an afternoon concert (fig. 2.3).

Orchestral music, the remnants of the nineteenth-century Germanic Romantic tradition, continued to be the link between Germany’s musical past, wartime cultural activities, and shattered postwar reputation. Although the Philharmonic paid lip service to Allied and Jewish composers in the postwar period, the ensemble performed mostly the same pieces as they had under National Socialism, as the orchestra made use of their standing under the American occupiers to give sonic space to German postwar suffering. Such suffering was not only expressed through repertoire but also by those who played it. When Furtwängler agreed to give a series of seven performances in the Soviet, British, and American sectors, he selected Beethoven to be the central repertoire of his programs. The city’s musical community was in a state of frenzy when the conductor’s plane landed at Tempelhof on the morning of May 22, 1947. Potential audience members waited more than fourteen hours outside the Titania Palast to try and hear one of his concerts. Black market prices ranged from 300 to 500 RM per ticket.60

Figure 2.3. Berlin concertgoers on their way home, early 1944. bpk Bildagentur. Photograph by Hanns Hubmann. Art Resource, New York.

His first performance on May 25 eerily echoed the conductor’s return twelve years earlier after his resignation from the RMK, featuring the same repertoire: Beethoven’s Fifth and Sixth Symphonies as well as the Egmont Overture. Yet the program notes for the evening, written by Berlin musicologist Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt, recast Furtwängler in the image of some of the nineteenth and twentieth century’s greatest Jewish musicians. According to Stuckenschmidt, Furtwängler was “an eminently spiritual musician in the vein of Gustav Mahler,”61 a champion of not only the works of Beethoven, Brahms, and Bruckner but also the music of Arnold Schoenberg. Stuckenschmidt connected prewar and postwar humanism by omitting any reference to the Third Reich, instead writing that Furtwängler’s absence between 1945 and 1947 was because the conductor wanted to devote himself solely to composition, an activity he greatly enjoyed but had little time for because of the Philharmonic’s schedule. At the concert’s conclusion, the audience applauded for fifteen minutes, and Furtwängler returned to the stage seventeen times for bows. Eventually, he resorted to bowing in his overcoat as a signal he wanted to go home. Even though Bitter wrote in his weekly report, “It was an honest music success, no political demonstration and the Phil played beautifully,”62 at the conductor’s concert with the Staatskapelle a few days later, Bitter noted the raucous applause carried “a political tinge.”63 The Americans may have cleared Furtwängler in a court of law, but they were uncertain how to handle his presence in the divided city, especially his appearance with a Soviet-licensed ensemble.

The Berlin press reviews of Furtwängler’s return were generally glowing. One Soviet news agency used battle metaphors to describe the conductor’s performance (“fierce combat” or erbitterter Kampf), concluding that “Egmont is the victim”64 at the overture’s conclusion. Yet “victim” (Opfer) in 1945 certainly carried other connotations, leading to uneasy comparisons with the more recently designated “victims of National Socialism,” a category of civilians who survived Nazi persecution.

Because most of the players had not performed under Furtwängler’s baton, his return heralded continuity rather than a cultural zero hour. Yet the conductor’s appearances were not received with wholehearted enthusiasm in all quarters. “With Furtwängler playing Brahms and Bruckner in the same way as [if] nothing happened in the past . . . all the hopes that something has changed since ’45 are gone,”65 one Berlin composer wrote a friend in England. Allied officials expressed similar misgivings; as an American official admitted, “[to] hear about Furtwängler having great triumphs in Berlin, I wonder what role music can fulfill in the political re-education of the German people.”66 The uproar surrounding Furtwängler’s return concerts was also about the rubbled bourgeois concert experience. How could the nineteenth century’s monumental symphonies reflect the twentieth-century postwar soundworld?

Despite his lengthy battle to be reinstated by the Americans, Furtwängler led the Philharmonic in only twelve concerts during the 1947 and 1948 season, a meager number in comparison to Celibidache’s seventy-six. His life in Switzerland provided the best working conditions he had experienced in over a decade, while Berlin’s rubbled cityscape could only present challenges, shortages, and controversies.67 Yet if Furtwängler had stayed in Hitler’s Reich to give the Germans hope during their darkest days, then why in the city’s postwar hour of need would he retreat to Clarens, a little corner of the world seemingly untouched by recent history?

Rubble City

Conditions in Berlin were about to take a dire turn, as the June 1948 currency reform in West Germany and West Berlin so angered the Soviets that Stalin embarked on a drastic plan of action to force the Western Allies out of the city. The Russians severed all ground supply routes to West Berlin by taking advantage of a loophole in the Potsdam Agreement and beginning what would become a nearly yearlong blockade. Furtwängler was scheduled to conduct the Philharmonic in July, appearing alongside violin prodigy Patricia Travers and harpsichordist Ralph Kirkpatrick, both American musicians invited as part of the ICD’s visiting artist program. The conductor canceled only ten days in advance, and the Philharmonic musicians were irate. As Celibidache admonished his senior colleague, “Your not coming was all the more incomprehensible as you were already in Munich,” complaining, moreover, that Furtwängler’s upcoming Beethoven cycle with the Vienna Philharmonic “also does not exactly please the orchestra.”68

The “inhuman conditions through which the Russians were trying to dominate the city,”69 as one cultural officer wrote, made it necessary to feed West Berliners through airlifts. Burdened by travel restrictions and the currency reform alike, Bitter despaired as inflation made concert tickets unaffordable for many Germans. The blockade made the Philharmonic’s schedule a point of contention between Allied cultural officers, as the Americans began pressuring the orchestra to stop performing under Soviet auspices. Thomas R. Hutton, the acting Information Services Branch chief (in lieu of John Bitter, who was away at a conducting engagement in Göttingen), wanted the ensemble’s managers to cancel all upcoming concerts in Russian-occupied territory, despite scheduled appearances at the broadcasting studio on Masurenallee for “The Voice of Moscow,” and other performances planned across the Soviet zone in Halle, Schkopau, Leipzig, and Wolfen. Even though Hutton was loath “to hear democracy, democratic government, and Military government in Germany villified [sic],”70 he did not have the military authority to ban the orchestra from appearing under Russian auspices. While an October 7 article titled, “Terror against the Philharmonic,” appearing in the Soviet organ Neues Deutschland, claimed it was the Americans who forbade the ensemble from performing in Soviet territory, the ensemble put the issue to a vote the following day. The orchestra realized that if they wanted to remain in the American sector, certain sacrifices would have to be made, and voted seventy-three to one (with seven musicians abstaining) to stop giving concerts at the Soviet broadcasting studio. Although decided by a democratic process, there was little doubt the Americans were pleased.

Destroyed venues, compromised musicians, and the ruins of a once monumental repertoire became the sound of German suffering in the Berlin Philharmonic’s postwar performances. The orchestra became a sort of ensemble in residence in its own city as American authorities regulated the Philharmonic’s repertoire, musicians, conductors, and performance schedule. From Horst Wessel Lied to The Stars and Stripes Forever, the ensemble survived because it was adaptable, heeding first the demands of the National Socialists and later those of the occupiers to continue concertizing.

Notes

1. Ruth Andreas-Friedrich, Berlin Underground: Diaries, 1945–1948 (New York: Paragon House, 1984), 310.

2. Thomas Eickhoff, Politische Dimensionen einer Komponisten-Biographie im 20.Jahrhundert: Gottfried von Einem (Stuttgart: Steiner, 1998), 76; and Matthias Strässner, Der Dirigent Leo Borchard: Eine unvollendete Karriere (Berlin: Transit, 1999), 213.

3. Berlin Philharmonic Program, March 1943, Berlin Philharmonic Archive.

4. “Das Berliner Philharmonische Orchester nach dem zweiten Weltkrieg,” 2–4; and Dienstbuch, G 100, Berlin Philharmonic Archive.

5. Berlin Philharmonic Programs, May 26, 1945, and March 11, 1935, Berlin Philharmonic Archive. For information about the recovery of music by Jewish composers, see Erich Hartmann, Die Berliner Philharmoniker in der Stunde Null: Erinnerungen an die Zeit des Untergangs der alten Philharmonie vor 50 Jahren (Berlin: Werner Feja, 1996), 37.

6. Andreas-Friedrich, Battleground Berlin, 35.

7. Anonymous account in Peter Muck, ed., Einhundert Jahre Berliner Philharmonisches Orchester (Tutzing: H. Schneider, 1982), 2:190.

8. Nicolas Nabokov, “Boris Blacher,” in Heribert Henrich and Thomas Eickhoff, eds., Boris Blacher: Archiv zur Musik des 20. Jahrhunderts, vol. 7 (Berlin: Fuldaer, 2003), 9.

9. Wolf Lepenies, “Eine (fast) alltägliche deutsche Geschichte,” in Misha Aster, Das Reichsorchester: Die Berliner Philharmoniker und der Nationalsozialismus (Munich: Siedler, 2007), 19; and Hartmann, Die Berliner Philharmoniker in der Stunde Null, 6–7.

10. There are some discrepancies concerning the date of the last Philharmonic concert before Germany’s surrender. April 16 is confirmed by Hartmann and by the daily planners of several other musicians, yet a 1956 pamphlet printed by the ensemble titled, “Das Berliner Philharmonische Orchester nach dem zweiten Weltkrieg,” lists April 8 as the final concert. Pamela Potter names April 11 as the final performance, held as “a concert for Mr. Speer.” For more information, see Aster, Das Reichsorchester, 326; Pamela Potter, “The Nazi ‘Seizure’ of the Berlin Philharmonic,” in Cuomo, National Socialist Cultural Policy, 58; Hartmann, Die Berliner Philharmoniker in der Stunde Null, 28; and Dienstbuch G 100 and 335, Berlin Philharmonic Archive.

11. Schlövogt, Dienstbuch 335, January 1945 to December 1945, Berlin Philharmonic Archive.

12. Suicide had grown increasingly common. In 1945 alone, some 7,057 Berliners killed themselves rather experience an uncertain postwar world.

13. W. Byford-Jones, Berlin Twilight (London: Hutchinson, 1947), 69.

14. Henry Alter, interview by Brewster Chamberlain and Jürgen Wetzel, May 11, 1981, B Rep. 037, Nr. 79–82, Landesarchiv, Berlin; and Philharmonic Concert Program, July 8, 1945, Berlin Philharmonic Archive.

15. Strässner, Der Dirigent Leo Borchard, 230. Although the broadcasting studio on Masurenallee was in the British sector, the Soviets refused to relinquish the most powerful radio transmitter in all of Germany.

16. Henry Alter, interview by Brewster Chamberlain and Jürgen Wetzel, May 11, 1981, B Rep. 037, Nr. 79–82, Landesarchiv. The German original reads “Ich glaube wirklich, dass wir das Berliner Philharmonische Orchester gerettet haben.”

17. Bitter, “Weekly Theater and Music Report,” April 30, 1947, RG 260, Box 241, Records of the Education and Cultural Affairs Division (E&CR): Records Relating to Music and Theater, NARA II. For more information on the denazification of the Berlin Philharmonic, see Walter Hinrichsen, “Members of the Philharmonic Orchestra Berlin Being Discharged in Accordance with Denazification Policy in the U.S. Zone,” June 25, 1946, RG 260, Box 237, Records of the Education and Cultural Affairs Division: Records Relating to Music and Theater, NARA II; Forck, Variationen mit Orchester, 20, 43, 54; and Fritz Trümpi, Politisierte Orchester: Die Wiener Philharmoniker und das Berliner Philharmoniche Orchester im Nationalsozialismus (Vienna: Böhlau, 2011), 113.

18. Hogan, “Weekly Report,” May 23, 1946, RG 260, Box 239, Records of the Education and Cultural Resources Branch, Records Relating to Music and Theater, NARA II.

19. Frederic Mellinger, “Commandatura Meeting, Denazification—Berlin Philharmonic,” May 29, 1946, RG 260, Box 237, Records of the Education and Cultural Affairs Division: Records Relating to Music and Theater, NARA II.

20. John Bitter to M. Wohlthat, October 2, 1948, RG 260, Box 97, Office of Military Government, Germany (OMGUS), Records of the Berlin Sector, NARA II. See also John Bitter, “August 15–31, 1947 Report,” National Archives Records: Shipment 4, Box 8-1, Folder 2, May 1946 to November 1948, B Rep. 036 Nr. 4/8-1/2, Landesarchiv; and Michael Josselson, “Ration for Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra,” January 7, 1948, RG 260, Box 97, Office of Military Government, Germany (OMGUS), Records of the Berlin Sector, NARA II.

21. Berlin Philharmonic Management to Information Control Services, January 3, 1948, RG 260, Box 97, Office of Military Government, Germany (OMGUS), Records of the Berlin Sector, NARA II.

22. Andreas-Friedrich, Battleground Berlin, 27.

23. Ibid., 312.

24. “One Man Can Save German Music: Leo Borchard,” Newsweek, August 27, 1945, 62–64.

25. Klaus Lang, Celibidache und Furtwängler: Der große philharmonische Konflikt in der Berliner Nachkriegszeit (Munich: Wissner, 2010), 19.

26. Strässner, Der Dirigent Leo Borchard, 235; Philharmonic Concert Program, August 25, 1945, Berlin Philharmonic Archive.

27. “Music: Rhythm in Berlin,” Time, September 10, 1945; Amy C. Beal, New Music, New Allies: American Experimental Music from the Zero Hour to Reunification (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 15; and the Foundation for Research in the Afro-American Creative Arts, “W. Rudolph Dunbar: Pioneering Orchestra Conductor,” in The Black Perspective in Music 9/2 (Autumn 1981): 193–225. With banjo players hard to find in Europe, Dunbar had already obtained Still’s permission to omit the part in the symphony’s third movement. Charles William Latshaw, “William Grant Still’s Afro-American Symphony: A Critical Edition” (PhD diss., Indiana University, 2014), 8.

28. “Negro Wins Plaudits Conducting in Berlin,” New York Times, September 3, 1945.

29. “Music: Rhythm in Berlin,” Time, September 10, 1945.

30. Heide Fehrenbach, Race after Hitler: Black Occupation Children in Postwar Germany and America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005), 17–45; David Monod, Settling Scores: German Music, Denazification, and the Americans, 1945–1953 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 240; and Eugene Davidson, The Death and Life of Germany: An Account of the American Occupation (New York: Knopf, 1959), 277. For more recent work on the intersections of race and classical music in Germany, see also Kira Thurman, “Singing the Civilizing Mission in the Land of Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms: The Fisk Jubilee Singers in Nineteenth-Century Germany,” Journal of World History 27, no. 3 (September 2016): 443–71; and Kira Thurman, “Black Europe: A Useful Category for Historical Analysis,” Black Perspectives: African American Intellectual History Society Blog (December 2016).

31. Helmut Schlövogt, Dienstbuch G 335, September 2, 1945, Berlin Philharmonic Archive.

32. “W. Rudolph Dunbar: Pioneering Orchestra Conductor,” 205.

33. “American Conducts Berlin Philharmonic,” Journal-Courier, September 3, 1945.

34. Toby Thacker, Music after Hitler, 1945–1955 (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2007), 56.

35. “National Socialists Oust Busch as Orchestra Conductor of Dresden Opera House,” New York Times, March 7, 1933; Fritz Busch, Pages from a Musician’s Life (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1971), 198–211; Hartmann, Die Berliner Philharmoniker in der Stunde Null, 43; and correspondence from T. R. M. Creighton to Leonie [last name unknown], undated, Max-Reger Institut, Brüder-Busch-Archiv, Karlsruhe. My thanks to Peter Berggren for sharing this letter with me.

36. Quoted in Lang, Celibidache und Furtwängler, 26.

37. Schlövogt, Dienstbuch 335, August 28, 1945, Berlin Philharmonic Archive.

38. Lang, Celibidache und Furtwängler, 389.

39. Beschluss des Magistrats in der Sitzung am 24. September 1945, C Rep. 120, Nr. 1692, Landesarchiv; “License no. 501 Issued to One Sergiu Celibidache for the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra,” November 1945, RG 260, Box 238, Records of the Education and Cultural Affairs Division: Records Relating to Music and Theater, NARA II; Lang, Celibidache und Furtwängler, 77; Muck, Einhundert Jahre Berliner Philharmonisches Orchester, 205; and Berlin Philharmonic Program, September 15, 1945, Berlin Philharmonic Archive.

40. Max Butting, Musikgeschichte, die ich miterlebte (Berlin: Henschel, 1955), 233. See also Monod, Settling Scores; and Sergiu Celibidache, The Berlin Recordings, 1945–47, Audite, 2013. Bitter was also an amateur composer who looked for opportunities to perform his work, organizing the premiere of his First String Quartet at Haus am Waldsee, an outdoor concert venue in Zehlendorf.

41. John Bitter, interview by Brewster Chamberlain and Jürgen Wetzel, November 6, 1981, B Rep. 037, Nr. 79–82, Landesarchiv.

42. Berlin Philharmonic Program, December 10, 1945, Berlin Philharmonic Archive. See also Beal, New Music, New Allies, 15–16. For more concerning Bitter’s conducting, see Monod, Settling Scores, 119–21.

43. Henry Alter, interview by Brewster Chamberlain and Jürgen Wetzel, May 11, 1981, B Rep. 037, Nr. 79–82, Landesarchiv.

44. W. Phillips Davison, A Personal History of WWII: How a Pacifist Draftee Accidentally Became a Military Government Official in Postwar Germany (Lincoln, NE: iUniverse, 2006), n.p.

45. Heinz v. Cramer, “John Bitter im Haus der Kultur,” Berlin am Mittag, July 12, 1947.

46. Dr. John Bitter Collection, Box 1, Folder 2, University of Miami Libraries, Coral Gables, Florida. See also Monod, Settling Scores, 119–21.

47. Eric Clarke, “Memorandum: Captain John Bitter, Conductor,” January 15, 1947, RG 260, Box 243, Records of the Information Control Division (ICD): Records of the Division Headquarters, 1945–49, NARA II.

48. Quoted in Gabriele Clemens, Britische Kulturpolitik in Deutschland 1945–1949: Literatur, Film, Musik und Theater (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 1997), 201.

49. Hartmann, Die Berliner Philharmoniker in der Stunde Null, 42.

50. Eric Clarke, “John Bitter,” January 14, 1948, RG 260, Box 134, Records of the Information Control Division (ICD): Central Decimal File of the Executive Office, 1944–49, NARA II.

51. Robert McClure, “For Release 21 February 1946,” RG 260, Box 43, Records of the Information Control Division (ICD): Records of Division Headquarters, 1945–49, NARA II.

52. Winthrop Sargeant, “Europe’s Culture,” Time, November 4, 1946, 56.

53. Wilhelm Furtwängler, Denazification File, December 17, 1946, RG 260, Box 237, Records of the Education and Cultural Resources Branch, NARA II.

54. Elizabeth Janik, Recomposing German Music: Politics and Musical Tradition in Cold War Berlin (Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill, 2005), 134–39.

55. John Bitter, “Theater and Munich Report,” October 24, 1946, RG 260, Box 239, Records of the Education and Cultural Resources Branch, NARA II.

56. Furtwängler, Denazification File, December 17, 1946, RG 260, Box 237, Records of the Education and Cultural Resources Branch, NARA II.

57. Susanne Stähr, “Die Ära Furtwängler,” in Forck, Variationen mit Orchester, 195–96.

58. Interview with Henry Alter conducted by Brewster Chamberlain and Jürgen Wetzel, May 11, 1981. B Rep. 037, Nr. 79–82, Landesarchiv.

59. Ian Baruma, Zero Hour: A History of 1945 (New York: Penguin, 2013), 4. Baruma’s father, then a Dutch law student brought to Germany as a forced laborer, recalled Furtwängler’s concerts as one of his few happy memories from the war years.

60. “500 Mark für Furtwängler-Karte,” Der Spiegel, May 31, 1947.

61. Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt, Berlin Philharmonic Program Notes, May 25, 1947, Berlin Philharmonic Archive.

62. John Bitter, “28 May 1947 Report,” National Archives Records: Shipment 4, Box 8-1, Folder 2, May 1946 to November 1948, B Rep. 036 Nr. 4/8-1/2, Landesarchiv. See also “Furtwängler wieder in Berlin,” Frankfurter Neue Presse, May 5, 1947.

63. John Bitter, “17 July 1947 Report,” National Archives Records: Shipment 4, Box 8-1, Folder 2, May 1946 to November 1948, B Rep. 036 Nr. 4/8-1/2, Landesarchiv.

64. Allgemeine Deutsche Nachrichtendienst, May 27, 1947, Berlin Philharmonic Archive.

65. Boris Blacher to William Glock, undated letter, Boris Blacher Papers, Folder 362, AdK.

66. Davidson Taylor quoted in Monod, Settling Scores, 214.

67. Lang, Celibidache und Furtwängler, 102. Elisabeth Furtwängler, the conductor’s wife, claimed there were several reasons her husband did not resume his former Philharmonic schedule: the vitriol of the international press, numerous other conducting invitations, and his desire to devote more time to his first love, composition.

68. Lang, Celibidache und Furtwängler, 176–78.

69. Eric Clarke, “Review of Activities for August 1–15,” Records of the Education and Cultural Relations Division (E&CR): Records Relating to Music and Theater, RG 260, Box 242, NARA II; Ernst Fischer and Ernst Fuhr, Berlin Philharmonic Schedule, September 26 to December 25, 1948, RG 260, Box 97, Office of Military Government, Germany (OMGUS), Records of the Berlin Sector, NARA II; and John Bitter, “July 1948 Report,” National Archives Records, Shipment 4, Box 8-1, Folder 2, May 1946 to November 1948, B Rep. 036, Nr. 4/8-1/2, Landesarchiv. For nearly a year, the Western Allies, and particularly American forces, piloted 277,500 flights to Tempelhof Airport, delivering 2.3 million tons of food. The Soviet Blockade lasted until May 12, 1949. See also Tony Judt, Postwar: A History of Europe since 1945 (New York: Penguin, 2005), 146; and Monod, Settling Scores, 183–95.

70. Tom R. Hutton, “Philharmonics [sic] Concerts under Soviet Auspices,” October 7, 1948, RG 260, Box 97, Office of Military Government, Germany (OMGUS), Records of the Berlin Sector, NARA II.