EMBODIED AND DISEMBODIED VOICES

AS HENRY GLUSKI FLEW OVER BERLIN BEFORE LANDING at Tempelhof Airport in August 1945, he could scarcely believe the cityscape he witnessed. The ruins stretched as far as he could see—monuments to carpet-bombing and the violent street fighting of the war’s final weeks. Nineteen-year-old Gluski had just accepted a broadcasting position with Berlin’s American Forces Network (AFN), the radio station of the American military government designed for American GIs stationed in Berlin. Because he was the youngest and most inexperienced, Gluski was given the radio programs no one else wanted to moderate. His assignments included the early, early morning show and the weekly Quadripartite Symphony Hour. He chose mostly nineteenth- and twentieth-century repertoire—namely, the works of Jewish composers, including Mahler and Mendelssohn, believing their music held reeducational value for any German listener who might be tuning in.1

In a city that more closely resembled a moonscape than a metropolis, radio provided a link to the outside world. As historian Monica Black writes of the rubbled landscape of 1945, “Ruins and the graves of the dead had come to comprise the city’s topography and become part of a new, postwar way of seeing.”2 Yet the war had also created a new postwar way of hearing, as the destruction left its imprint on the aurality of the city. Without walls, doors, windows, or roofs, the ruins allowed sound to travel from dwelling to dwelling without any impediment. Radio blurred the boundaries of musical/sonic publicness and privacy, to evoke Georgina Born’s terms, as sound could now freely travel. Radio waves lacing through one ruin to another created what R. Murray Schafer has called schizophonia, or the confusion between sound happening in real time and its electroacoustic counterpart. As British officer George Clare recalled, “My most striking first impression was not visual but aural: the muted echoes of a battered city.”3 Other visitors found the ruins even took on a melody of their own: “Amid the sour wreckage of a spotted city this music of a sweet and nostalgic nature was often to be heard,”4 Allied soldier Richard Brett-Smith noted in his memoir.

While much scholarship has focused on the visually arresting aspects of ruins, less attention has been paid to their sound. One did not just see the ruins; one also heard them. These “musically imagined communities,”5 created and informed by postwar German radio, offer a window into the shared traumatic experiences of the air war. This chapter explores the tensions between ruin listening in the private and public spheres. The disembodied voice of the radio created a community of listeners while still dividing the listening public who had to choose between the American- and Soviet-supported stations. Yet radio heard in the privacy of one’s home stood in sharp contrast to the proliferation of public concerts in the ruins throughout postwar Germany. As Berlin musicians returned to the bombed craters of their former venues to stage performances, these ruin concerts permitted ensembles to engage with notions of German suffering by reclaiming churches, palaces, and concert halls destroyed by Allied bombing. These performances were among the first overt expressions of German victimhood, as they aestheticized the rubble left by the air war. Through radio waves and ruin performances, Berlin’s embodied and disembodied soundscapes brought political conflict and musical production in direct confrontation with each other.

Rubble Radio

As tensions between East and West Berlin waxed and waned, radio had the ability to easily cross the city’s borders, unifying its listeners not by geography but by aurality. With fewer spaces in which to give concerts and considering the difficulties to arrive at these venues, radio provided the Allies and German civilians with a practical alternative. The sonic ruins of the city soon became their own recital halls, creating what Benedict Anderson has termed unisonality, by generating the possibility for “people wholly unknown to each other to utter the same verses to the same melody.”6 To form these aural communities across urban divides, the Soviets emphasized the affinities between German and Russian classical composers, taking a socialist realist approach, while the Americans promoted modernism and new music over the airwaves. The war and its sonic aftermath radically changed the way in which Germany’s composers heard their music, and radio was at the center of this revelation. Even though their methods may have differed, both stations commissioned a number of important postwar works from the city’s composers. These compositions used various musical forms such as cantatas and radio plays to broadcast traumatic experiences of bombing, injury, and death. Although the Allies may have believed they tightly controlled all aspects of radio production, the airwaves provided mass media possibilities to broadcast experiences of civilian suffering in occupied Berlin.

During the Nazi era, German radio had been a political instrument intimately tied to the regime. In Weimar Germany only an estimated five hundred thousand Germans subscribed to radio; by 1930, there were more than three million listeners. As the harbinger of news, entertainment, distraction, and propaganda, radio ownership skyrocketed in 1933 after Goebbels commissioned the cheap and readily available Volksempfänger (people’s receiver). With the declaration of war in 1939, radio’s mass media possibilities were needed to keep the morale of civilians and soldiers high, as Germany became the second largest radio-listening public in Europe, just behind England. Music on the radio reassured the population of final and ultimate victory, creating and strengthening a sense of a national community through the broadcast medium. When Hitler wrote in the late 1930s, “We should not have conquered Germany without . . . the loudspeaker,”7 the statement did not seem an exaggeration.

Popular radio programs such as the Request Concert for the Wehrmacht, a bimonthly broadcast featuring musical dedications connected the people’s community (Volksgemeinschaft) at home with soldiers at the front. (The program even inspired the 1940 Nazi propaganda film Request Concert, which used the radio broadcast as a vital component in the love story between pilot Herbert Koch and Inge Wagner.) Celebrations like Heroes’ Commemoration Day (Heldengedenktag) were broadcast throughout the country, opening with music from the Staatsoper.8

In January 1945, as the Wehrmacht suffered crippling losses in the east and the Allies accelerated their bombing campaigns against German cities, Goebbels turned on his radio, catching the final movement of the Eroica Symphony featuring conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler and the Vienna Philharmonic. “How beautiful and refreshing it is to immerse oneself in this world,”9 Goebbels wrote in his diary before returning to the stark realities of the Soviet offensive. Radio played a vital role in the sonic landscape of fascism, and yet, as Annegret Fauser notes, “The lived sonic experience of that world war often remains unrecognized.”10 A large part of this lived soundscape was the air raid. After the radio sounded an initial warning, sirens would wail. Larger cities had thousands of them, as the alarm’s radius was only sixteen hundred feet. Through its tones, the siren signaled the four stages of the raid: (1) stay alert, (2) seek shelter within the next ten minutes, (3) bombing may be over, and (4) the raid is finished. Once in the cellar, many Germans brought their radios with them for updates and entertainment purposes. Radio sets permitted the government to enter the private sphere at any time to interrupt with announcements and warnings. In order to ensure that radio broadcasts could continue uninterrupted during evening bombing raids, Reich Radio (Reichsrundfunk), the most powerful transmitter in the country, broadcast from a Berlin bunker on Masurenallee.11

But radio’s possibilities cut both ways for the Reich as propaganda posters warned that “Enemies listen!” (“Feinde hört mit!”)—suggesting that civilians not discuss political or military matters in public or over the phone where enemy ears might hear. These attempts to criminalize information sharing and illegal acts of listening extended to prohibitions on foreign radio stations, though there were few real sanctions for tuning into channels from abroad. By dictating how to listen, and how not to listen, Kurt K., a teenager during the Third Reich, later recalled, “These state-subsidized radio sets (Volksempfänger) had the purpose of keeping the people acoustically under control.”12

Hitler’s fifty-sixth and final birthday was marked with broadcasts of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony while his suicide ten days later was mourned with the Funeral March from the Eroica Symphony. It is for this reason that Brian Currid notes the stereotypical soundtrack of Nazi Germany involves “the roar of a crowd, the echo of a goose step, the sound of march music, and the resonant voice of Adolf Hitler.” Such a sonic imaginary forms a stark contrast with musical metaphors of the regime’s collapse—of “the music of the roaring of enemy planes” and “a crescendo in the fighting.”13 Radio was the voice of the people’s community, and it would soon become the most powerful and far-reaching mass medium in destroyed Germany.

Soviet and American Broadcasting in Berlin

With Nazi Germany’s unconditional surrender, the Allies quickly broke up Greater German Radio, controlled by the Reich Broadcasting Corporation, and instead reestablished regional stations according to the model used before 1933. The Americans ran five radio stations across Germany: RIAS Berlin, Radio Bremen, Radio Frankfurt, Radio Munich, and Radio Stuttgart. The Soviets, British, and French Allies supported one station each: Radio Berlin, Northwest German Broadcasting (NWDR), and Southwest Broadcasting (SWF), respectively. The Soviet Radio Berlin and American RIAS created reeducational programing “to make available to the German people something of the cultural heritage of which they have been kept ignorant during the Nazi period.”14 Berlin broadcasts included everything from programs promoting new music to news bulletins. The stations also commissioned works from the city’s composers, who produced scores about the trauma and suffering of war. The broadcast medium allowed compositions about civilian victimhood to resound freely through the ruined spaces of Berlin.

Yet combing through the files related to radio in postwar Berlin raises certain challenges—namely, that these early postwar broadcasts survive only on paper, not through recordings. In their work on British broadcasting in the interwar period, Paddy Scannell and David Cardiff admit, “There is an inescapable paradox at the heart of this project of which we have been acutely aware all along—our object of study no longer exists.”15 A lack of recordings need not constitute a methodological gap, however, as scholars such as Josephine Dolan have pointed out. Physical materials can reveal the inherent tension in the medium of radio, as “an interface between writing and talk; between the written and the spoken word; between the competencies of reading and listening.”16 In the case of rubble music, there exists a wealth of archival radio documents in the form of memorandums, scripts, and musical scores.

By analyzing where the sonic and the written archives intersect, this section hears rubble music through broadcasts supervised by the Allies but largely written, staffed, and heard by German civilians. “Sound is an artifact of the messy and political human sphere,”17 Jonathan Sterne wrote in The Audible Past, and rarely was sound so fraught as in the destroyed capital. Gathering around the radio, a prized possession, remained the most ubiquitous form of information sharing possible in the postwar period. A functioning radio meant a link to other city-dwellers as well as the outside world, a connection that made having access to a functioning radio a necessity (fig. 4.1).

Figure 4.1. Berlin Radio Repair Workshop, Radio Ohnesorg, 1947. SLUB Dresden/Deutsche Fotothek. Photograph by Richard Peter.

Once the Soviets arrived in Berlin, they seized Germany’s most powerful radio transmitter on Masurenallee in Charlottenburg. By mid-May, Radio Berlin (Rundfunk Berlin) broadcast news, special programs, and music for nineteen hours a day, as one of the few sites of cultural production to remain in prewar condition. The station also aired live concerts, the first of which took place on May 18 and was also broadcast to Moscow. Another live performance on May 27 showcased musicians from the city’s opera houses led by Leopold Ludwig. The program contained pieces by German and Russian composers, including excerpts from Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro and Don Giovanni, Beethoven’s Fidelio, and Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony. The broadcast was a symbolic gesture that was as much about showing unity between two former enemy countries as it was about who was left in Berlin to perform.18

In the first few weeks of broadcasting, the Soviets primarily played the music of Russian composers like Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, and Glazunov, and Austro-Germanic composers such as Brahms, Haydn, Mozart, and Schubert. The station marked Richard Strauss’s eighty-first birthday on June 11 with a special broadcast featuring nearly two hours of his music. Radio Berlin also featured news, morning gymnastics, and Volksmusik, in addition to programs tailored to the perceived taste of German audiences such as “Music for the Housewife,” “The Heartbeat of Berlin,” and “The ABCs of the Lighthearted Muse,” a program that featured interviews with artists persecuted by the regime. The Soviet occupiers sought to use the airwaves to promote a common musical ideology, as their station would maintain the longest hours of all the Allies, often broadcasting past midnight.19

When the American military arrived in Berlin in early July, they, too, wanted to establish a radio presence as quickly as possible. On July 17, several GIs reached the city with orders to create Berlin’s AFN in under seventeen days. (AFN stations accompanied troop movement, and there were also branches in Munich and Bremen.) On August 4, AFN Berlin began broadcasting with a wire antenna strung between two trees, a 250-watt transmitter, and two trucks that contained additional equipment. Signing on with Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, the station could broadcast to only a two-mile radius. Despite its modest range, the station provided valuable news and music in the first several weeks of the occupation. By mid-August, AFN relocated to 28 Podbielskiallee, the requisitioned twenty-seven-room mansion of former Nazi foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop. (Ribbentrop was tried at Nuremberg and executed for war crimes in 1946.)20

Because AFN was designed for American GIs stationed in Berlin, the Americans realized that in order to rival the Soviet’s Berlin Radio, they would need to create another station tailored exclusively to German listeners. Wired Radio in the American sector, or DIAS (Drahtfunk im amerikanischen Sektor), began broadcasting on February 7, 1946. In a nod to the Soviet presence in the city, the Americans recognized Berlin’s “strong radio competition and the necessity for the Drahtfunk [radio] to stand out as a cultural instrument,”21 and by September, DIAS became RIAS, or Radio in the American Sector (Rundfunk im amerikanischen Sektor), after the station acquired a transmitter and greater broadcasting abilities. RIAS reserved approximately 55 to 60 percent of its airtime for music, much more space than the political or news departments received, and strictly broadcast only music between 12:00 a.m. and 6:00 a.m.22

The Americans also created the RIAS Chamber Choir, the RIAS Symphony Orchestra, and the RIAS Dance Orchestra to perform on air and to give live concerts. There was money for these “extras” by American standards due to the difference in the way German and American radio stations were funded. In Germany, stations were nationalized, collecting a subsidy from the government that freed them any dependence on commercial sponsors. Due to their state-guaranteed backing, they had the financial freedom to fund orchestras and choirs of extremely high caliber. As a noncommercial venture, the stations were nonprofit and paid their musicians and personnel well, making West German radio a highly desirable place to work. New music was supported because there was no risk of losing sponsors. This proved in striking contrast to the American system, where the roughly one thousand privately run stations were dependent on advertising.23

Bringing American music to postwar Germany was first suggested on May 23, 1945, by Information Control Division (ICD) radio section director Davidson Taylor. In civilian life, Taylor was CBS’s head of classical music broadcasting. An inordinately pragmatic man, Taylor recognized it would be difficult to distribute physical scores of American music in Germany. Radio provided an attractive alternative, for as an American military newsletter admitted, “In the absence of former entertainment sources—from cafes to concert halls—the German public expects radio to provide them with entertainment of a caliber comparable to pre-1933 production.”24 American planners were also aware that radio’s powers of distribution exceeded every other form of mass media and were keen to differentiate between mere entertainment and high culture, as “artists in the fields of music, theater, and radio can carry out a function of great importance in the fields of re-education.”25 Radio would not become the mere mouthpiece of the Allies, however, because each power still needed the help and talent of German civilians to create programs tailored to the wider civilian population.

Among the reeducation aims of the occupiers was to reintroduce music supposedly banned during the Third Reich, and radio became the most accessible method for the distribution of this music. Maintaining the pervasiveness of the “Nazi canon” or “Nazi index” of musical works under the Third Reich, the Americans used the legacy of degenerate music (Entartete Musik) to legitimate the importation of American classical music for the radio. Accordingly, RIAS created the program Studio for New Music (Studio für neue Musik). Because the ICD was interested in promoting “German composers prohibited under the Nazi regime for racial or political reasons” and “composers from outside Germany,”26 Studio for New Music aimed to reintroduce Berliners to music supposedly banned by the Nazis, including works by Igor Stravinsky, Paul Hindemith, and Anton Webern. Unbeknownst to the ICD, a number of the featured composers had, in fact, tried to align their work with the goals of the National Socialist state during the 1930s; as late as 1938, Stravinsky was trying to secure an invitation from his publisher, Schott & Sons, to conduct his music in Germany. Hindemith’s relationship to the Nazis was also less than one of staunch resistance (“I have been asked to co-operate, and have not declined,”27 he wrote to Ernst Toch in 1933), although in 1945, this was not widely known. Webern, too, had appealed to Nazi authorities in Austria, trying to convince them of twelve-tone’s merits.28

As the director of Studio for New Music, Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt was to become an integral part of the American cultural agenda. Educated in Berlin, Ulm, and Magdeburg and self-taught in theory and musicology, Stuckenschmidt had worked as a freelance writer and composer in Paris, Hamburg, Prague, and Bremen before coming to Berlin in the 1930s. Stuckenschmidt’s support for new music made his scholarship unwelcome in the Third Reich, and after his November 1934 Berliner Zeitung review of Berg’s Lulu-Symphonie (performed to a full house at the Staatsoper), he received an edict from the Reichsverband der deutschen Presse that his criticism possessed “a direction indubitably influenced from the Jewish side,”29 barring him from publishing in Germany. In the early 1940s, Stuckenschmidt was conscripted into the Wehrmacht as a translator and, after 1945, was held in an American-run prisoner-of-war camp in France where he again served as a translator, this time for the American military. While at the Attichy POW camp, Stuckenschmidt passed the time by drafting musicology lectures for fellow prisoners on topics from “Modern Opera” (“Die moderne Oper”) to “Wagner’s Prospects” (“Wagners Aussichten”). Returning to Berlin in 1946, Stuckenschmidt was offered a job by the ICD as the director of the Studio for New Music, to air Friday evenings on RIAS. He quickly realized his new alliance with the Americans could prove mutually beneficial; they provided him with a platform and financial support for his work, while the military government gained a vocal German ally for new music.30

Stuckenschmidt’s pro-and-contra episode format appealed to skeptical listeners and proponents of new music alike as he scripted every detail, recognizing the importance of these broadcasts as a way to (re)introduce Berliners to modern music. In “A Talk about Dissonances,” broadcast in November 1946, a musician (Stuckenschmidt) and a “friend of music” (Hermann Schindler) discussed the role of dissonance throughout Western classical music. Paul Höffer played music examples on the piano. The broadcast opened with an excerpt from Ernst Krenek’s Toccata and Chaconne op. 13, a piece based on the Bach chorale, Ja ich glaub an Jesum Christum. (Krenek fled Nazi Germany in 1938 and settled in the United States, although this is not mentioned in the dialogue.) The following conversation ensued:

FRIEND OF MUSIC (ENTERS QUICKLY): What is that noise you are making in here? It’s terrible!

MUSICIAN: (keeps playing)

FRIEND OF MUSIC: But would you please stop; that is absolutely unbearable!

MUSICIAN: (has continued to play, but now stops) What are you raving about? What you have just heard was a chorale from Krenek that was written more than twenty years ago.

FRIEND OF MUSIC: Do you seriously call this garble music?31

The musician points out that what might today be a consonance (i.e., a major triad) would have been considered a dissonance five hundred years ago (“You think only modern music brings about this impertinence?”).32 Stuckenschmidt’s character even compares Hindemith’s case, who, as he points out, left Germany on account of “his dissonances” (“seiner Dissonanzen”) to J. S. Bach’s, as the composer left his job in Arnstadt after his “novel sounds” (“neuartige Klänge”) greatly disturbed the congregation. Stuckenschmidt’s comparison rings hollow; fleeing Nazi Germany in the early 1930s and leaving Arnstadt for better working conditions in the early 1700s were widely disparate experiences. “A Talk about Dissonances” ultimately resists engaging with the trauma of exile. Similar scripts for “degenerate music” ensued, including music by Alban Berg, Béla Bartók, Arnold Schoenberg, Igor Stravinsky, Darius Milhaud, and Kurt Weill. It was, of course, no accident that all the featured composers who had fled Nazi Germany made their way for longer and shorter periods to the United States.

Aside from Stuckenschmidt’s broadcasts, RIAS frequently incorporated other programing that linked the American continent with the European musicians who had fled fascism. The station celebrated the centenary of Mendelssohn’s death with a weeklong series of his music from October 28 until November 4, 1947. But as much as the broadcasts were about Mendelssohn, they were also about promoting the safe haven that America had given many European-born conductors. With recordings featuring the Boston Symphony Orchestra led by Serge Koussevitzky and Dimitri Mitropoulos and the New York Philharmonic by Artur Rodziński, the broadcasts emphasized the fruitfulness of the American-European partnership.33

Despite RIAS’s efforts to reeducate Berliners, the station had difficulties building an audience in its early years. The primary problem was RIAS’s signal quality, which was not as strong as Radio Berlin. As a result, most Berliners in 1946 and 1947 were listening to the Soviet station regardless of the sector they lived in or their political views. An October 1946 RIAS survey revealed that 67 percent of the city listened to Berlin Radio compared to only 16 percent for RIAS. Despite these setbacks, the Americans were still convinced of RIAS’s strategic worth as a reeducation tool, acquiring a more powerful transmitter in January 1948 to improve their audibility and build a larger audience.34

East and West Berlin Commissions

American-controlled RIAS and Soviet Radio Berlin remained committed to commissioning works from Berlin’s composers. While this patronage fulfilled a didactic purpose—teaching audiences about the terrors of warfare and the moral bankruptcy of National Socialism—these pieces also served as sonic memorials to the suffering and trauma of German victims, a state- and occupier-sanctioned form of public mourning. In the period before the Berlin Wall or the Berlin Blockade, the occupiers freely commissioned works from composers on both sides of the city, regardless of the sector in which they lived.

Among the most prolific and politically savvy composers, and one who managed to win favor with both the Russians and the Americans, was Boris Blacher. Born in Russian-speaking Manchuria in 1903, Blacher studied music in Siberia and Harbin, China, before moving to Berlin to study architecture in 1922. Dissatisfied with his choice, Blacher soon enrolled at the Hochschule für Musik to study composition with Friedrich Ernst Koch. He enjoyed a moderately successful career as an arranger and composer and a brief appointment at Dresden Conservatory in 1938, although the Nazis dismissed him a year later. Blacher was one quarter Jewish and considered to be stateless, exempting him from service in the Wehrmacht and, of course, party membership. By 1945, Blacher and his wife, pianist Gerty Herzog-Blacher, were uniquely poised to become key players in Berlin’s musical scene. The composer took at position first at Paul Höffer’s International Music Institute and then at the Hochschule in 1946. John Bitter and Nicolas Nabokov were frequent guests in the Blachers’ Wilmersdorf home and secured extra food rations for the musicians. Nabokov, in particular, took an interest in the composer’s work and soon found that “Blacher was a living encyclopedia of music’s torturous and complex history,”35 as they spent long evenings discussing culture and politics.

Blacher’s postwar works frequently engaged with the individual’s struggle against societal injustice, and his radio opera, The Flood (Die Flut) (1946), a commission from Radio Berlin, was a thinly veiled allegory of the deprivations and corruption of the postwar period. The plot concerned four stock characters (young woman, young man, fisherman, old banker) who become trapped on a shipwreck awaiting low tide. Eventually, the young man murders the banker for his gold, departing with the young woman, who both dream of wealth and a life of leisure. The fisherman remains with the body as well as his delusions of a relationship with the young woman. The boat itself is a thinly veiled metaphor for National Socialism, and as musicologist Andrew Oster notes, the work is “a creative testament to postwar Berlin.” Scored for only five woodwinds and a string quartet, the radio opera premiered on December 20, 1946, over Radio Berlin (the first newly composed radio opera since the war) and was also staged in Darmstadt, Dresden, Hannover, and Heidelberg the following year.36

One year after Berlin’s fall to the Soviets, Radio Berlin also commissioned the composer to write music for a radio play, The Last Days of Berlin (Die letzten Tage von Berlin), by Wilhelm Hoffmann, director of the State Library at Württemberg. Blacher’s score accompanies Hoffmann’s retelling of the Soviet invasion, though references to unsavory elements such as rape or looting are, of course, omitted. The Last Days of Berlin premiered on April 30, 1946, marking the one-year anniversary of the occupation. Radio Berlin’s weekly magazine, The Radio, featured a synopsis of the radio play, calling The Last Days of Berlin “a radio kaleidoscope from the year 1945.”37 The article is accompanied by a series of drawings detailing the destruction, showing Berliners huddling in basements, buildings toppling onto tram tracks, and explosions near subway stations as civilians hurry for cover as Hoffmann called the Battle of Berlin “a witches’ sabbath,”38 describing the chaos and uncertainty of April 1945.

The score is typical of Blacher’s style, featuring driving rhythms and a clarity of line strongly influenced by Stravinsky, Milhaud, and Satie rather than by Austro-Germanic composers. Scored for piccolo, flute, oboe, two clarinets, bassoon, trumpet, trombone, bass, drum, and piano, the music is divided into six sections. Military drumbeats and diminished triads prevail within Blacher’s music, which accompanies the city’s fall. The second section is scored only for solo snare drum, presumably signaling the Nazi’s last stand and the realization their efforts were futile. Sections 5 and 6 are written alla Marcia, and with the sudden introduction of a march in the piano, marking the arrival of the Russians in Berlin.39

Across town in the eastern district of Prenzlauer Berg, Max Butting also resumed his work as a composer. Although a former party member, like many of his contemporaries, joining the Nazi Party did little to impede Butting’s postwar career, and in 1947, he became director of Radio Berlin’s Music Section. He drew from his previous experience working for Reich Radio during the 1930s, where he felt that the absence of an artistic director (a common practice in radio before 1933) meant that the station’s programming would sink to “the level of the listeners.”40 Butting preferred airing live performances rather than recordings, and he worked tirelessly to rectify what he perceived to be shortcomings in radio production, composing for ensembles and both Berlin radio stations.

When RIAS commissioned Max Butting to write a piece in 1948, the composer produced After the War: Four Cantatas for Mixed Choir and Chamber Orchestra. Among the few surviving documents concerning Butting’s work with the station is a brief autobiography. The composer writes that his music had been unwelcome since 1933 and that “public and private obstructions caused a creative pause”41 during the Nazi regime. In reality, he had turned his attention to running the family’s iron business. Yet no one at RIAS followed up on Butting’s claims of persecution; rubbled reputations and cityscapes went hand in hand.

Each cantata featured a text by the composer, representing the difficulties of life in postwar Berlin through the four seasons. In “IV. Winter,” Butting sums up life in Nazi Germany by writing, “Ten years ago we built a fortress, in the ashes and rubble of which we grovel today.”42 The cantata concludes with the plea, “Give us peace,” repeated five times, and the hope that the following spring will awaken Berliners from their “rubble misery.”43 These works are testaments to German suffering in the early postwar years, specific in regard to the deprivations but vague as to their causes. Instead, the seasons themselves present certain challenges for the narrator and are often the culprits of the city’s destruction. Butting’s text begs the question of whether he intended for his audience to identify each season with one of the occupiers—unpredictable and swift to render punishment? Most likely sung by the RIAS soloists and orchestra, no recording of this broadcast exists.

Ultimately, it was the Soviet Blockade of West Berlin, beginning on June 24, 1948, that did the most to boost RIAS listenership, giving the American station 80 percent of Berlin’s ears as RIAS increased their broadcasting to eighteen hours a day, double their previous amount. AFN broadcast twenty-four hours a day in order to keep American and British pilots awake as they flew in and out of Tempelhof Airport to deliver supplies.

Henry Gluski left AFN after two years at the station, relinquishing his work as moderator of the Symphony Hour. He had opened each show with the national anthems of all four Allied powers until 1946. An American general who heard the broadcast complained that Gluski should not include the Soviet anthem, and he was subsequently ordered to remove the music from the program. Circumventing the rules, he decided to open the Symphony Hour with excerpts from Prokofiev’s The Love for Three Oranges instead. He waited for a reprimand from his commanding officer, but it never came; none of his superiors knew the piece, or for that matter, who Prokofiev was. Engaging in his own kind of “musical sabotage,” Gluski continued broadcasting the Prokofiev throughout the resonant ruins of the city.44 The aurality of the cityscape forever changed, these radio broadcasts transformed craters and facades into sites of sonic protest, juxtaposing Allied propaganda with the sounds of German suffering.

Rubble Concerts

While the radio invited Berliners to contemplate the city’s destruction from the ruins of their former homes, other musical experiences in the rubbled cityscape were more public. In one of his first official outings in the capital, John Bitter heard the Berlin Chamber Orchestra perform the music of Haydn, Gluck, and Beethoven. Under the direction of Hans von Benda, who, in Bitter’s rendering, resembled, “a long, gaunt, emaciated, Christ-like figure,”45 the Dahlem concert proceeded smoothly until it began to storm. The roof, looming some forty feet above, was filled with holes that poured rain onto the listeners seated below. For the remainder of the concert, audience members rearranged their benches in a futile effort to avoid the water. The orchestra kept playing, and Bitter was both impressed and puzzled by the tenacious attempts to continue. Observing a similar contradiction between the urban debris and feverish cultural activity, one Time magazine correspondent wrote, “This vitality seems to bear an inverse relation to the amount of ruin that surrounds it.”46

The war’s destruction profoundly reshaped everyday musicalizing. In Berlin, Munich, Dresden, and Nuremberg, concerts continued in spite of, and sometimes even because of, the city’s physical devastation. German ensembles used urban rubble to give performances that were visually arresting, uncanny, and macabre as musicians returned to spaces destroyed by Allied bombing. The ruin concert expressed civilian suffering as musicians returned to the rubble of their former venues. These performances broke out across the country, staged by and for civilians and featuring the music of classical and romantic Austro-German composers. Berlin proved to be the paradigmatic location for ruin performances, and the cityscape took on a particular ruined aesthetic due to its largely nineteenth- and twentieth-century architecture. With steel girders providing the structural support for most buildings, rather than timber beams as in other city centers, the capital’s ruins towered skyward.47

As the city where, as Svetlana Boym wrote, “East and West play hide-and-seek with one another,” Berlin’s destroyed spaces soon became sites of public mourning and commemoration. Yet at the center of debates about German suffering and postwar culture remains the contentious issue of silence. Did the Germans openly embrace their role as victims of the air war? Or was the nation unwilling or unable to acknowledge the air war’s staggering death toll? In the wake of 1945, according to the well-trodden psychological diagnosis of Margarete and Alexander Mitscherlich, Germany experienced an “inability to mourn” for their depraved leader, thereby preventing the German people from working through their grief concerning the death, destruction, and defeat of their country. Hannah Arendt was similarly disappointed by what she considered “a lack of response” on the part of German intellectuals who were taciturn in regard to the country’s ruin. Even forty years later, literary scholar W. G. Sebald’s charge that postwar writers failed to document the Allied destruction of German cities, engaging in a kind of collective amnesia where only three novelists grazed the “landscape of ruins,”48 resounded through all forms of postwar culture. No genre or discipline seemed immune to accusations of silence.

Contrary to these claims, however, more recent scholarship has definitively shown that notions of German suffering played a prominent role in the country’s reconstruction. What Eric Langenbacher has termed German-centered memory, or the presumed experience of the average German civilian, reemerged almost immediately after the collapse of the Third Reich. As Robert Moeller argues, notions of German victimhood informed national identity in both Germanys. In the east, the perpetrators were Anglo-American imperialist bombers who had attacked German cities between 1942 and 1945, while in the west, the mass rapes committed by Red Army soldiers and the fate of prisoners of war still in Soviet captivity informed public debates about German victimhood. Similarly, Anna Parkinson condemns the “melancholic scholarship” resulting from the Mitscherlichs’ argument, noting that there were many early attempts to work through Nazi crimes intellectually and emotionally. Notions of German suffering after 1945 depended on where one looked or, perhaps more accurately, where one listened.49

Ruin music making was included in these initial responses to trauma. The city took on a particular soundscape, as music in the ruins distracted laborers from the monotony of their backbreaking tasks in more informal iterations of rubble music making. The ruins could be a place to rehearse (fig. 4.2) as workers tossed bricks to each other while the training choir (Der Aufbauchor) from Berlin’s Deutsches Theater sang, accompanied by an accordion and a double bass. The pun of “Aufbau,” literally meaning “to build up” (from aufbauen), could not have been lost on the singers and workers as the music accompanied the city’s physical reconstruction. Rubble music provides temporary relief from the work at hand: the painstaking effort to rebuild Berlin, brick by brick. A community of workers becomes a community of listeners as their workspace is transformed into a concert hall. Similarly, a trio of musicians in East Berlin celebrated Frauentag (Women’s Day) by playing for workers (fig. 4.3), because, as the accompanying newspaper article concluded, “with music, everything is easier,”50 a phrase that draws uncomfortable parallels to concentration camp uses of music. As scholars such as Shirli Gilbert, Guido Fackler, Joseph Toltz, and Wolfgang Benz elucidate, music making in the camps was often used as a terror tool. The problematic blurring of German civilians and forced Jewish laborers conflated their suffering in disconcerting ways.51

Figure 4.2. Music for the Reconstruction, 1953. Photograph by Hans-Günter Quaschinsky. Courtesy of the Bundesarchiv.

Music in Ruins

Aside from impromptu music making, performers also staged events that made full use of the ruin’s aesthetic possibilities. Many cities used their urban decay as a ready-made backdrop for performances featuring German musicians playing German music. Staged displays of cultural resilience, despite the destruction and suffering caused by the air war, proliferated across the country. As historian Michael Meng notes, “In film, literature, and photography, rubble became an integral component of German cultural memories of victimization,”52 and music, too, was part of this narrative thread.

On July 29, 1945, in the bombed ruins of St. Sebald Church in Nuremberg, a small group of musicians performed part 1 of Haydn’s The Creation (Die Schöpfung) for the first oratorio performance in postwar Germany. By the time members of the Teacher’s Choral Association (Lehrergesangverein) and the Nordbayerisches Landesorchester organized the rubble concert, the Americans had already occupied Nuremberg for more than three months. Because military authorities dissolved all organizations that had existed under the Nazis, conductor Karl Demmer recognized that he would need to obscure his musicians’ recent pasts (as well as his own) in order to perform. As the director of both ensembles, Demmer renamed them the innocuous-sounding Choir and Orchestra of the Concert Society (Chor und Orchester der Konzertgesellschaft e.V.). (Considering the Teacher’s Choral Association had 400 singers in 1938 and only 37 members by 1945, the organization scarcely resembled its prewar iteration.) Ostensibly, the St. Sebald parish office (Pfarramt) organized the performance, rather than the singer’s association (Verein), another attempt by Demmer to make the ensembles appear newly constituted after the cease-fire.53 For the July performance, the Nuremberg audience sat on tavern benches brought to the ruined choir of the church. Among the listeners were seventy members of the Wehrmacht still in uniform, and as one soldier later recalled, “After everything we lived through, we had to perceive it as a gift to be able to hear The Creation. . . . I was long defenseless against my tears, overcome by the music and by our misery.”54

Figure 4.3. A trio plays for Frauentag, 1953. Photograph by Schmidtke. Courtesy of the Bundesarchiv.

Shortly after the first concert, the Americans fired Demmer for his activities under National Socialism and hired conductor Rolf Agop to conduct the remaining performances. One witness likened the placement of the musicians and audience members to the Sermon on the Mount as Jesus delivered his message to the disciples, while another music critic marveled, “The audience was sitting on top of debris and rubble. In their hearts burned the longing for the indestructible.”55 By the time the five-concert series finished in September, around fourteen hundred people had visited the church to hear either part 1 or part 2 of The Creation.

In Munich, musical culture was similarly rubbled. In an article for the Paris edition of the Herald Tribune, American composer Virgil Thomson reported the city resembled “a construction in pink sugar that has been rained on,”56 though, like Berlin, concerts resumed immediately after the surrender. In August 1945 (fig. 4.4), a chamber ensemble performed in the ruins of Munich’s Grottenhof, a surviving courtyard of the city’s Residenz. Once a centerpiece of the city’s cultural heritage, the Residenz had previously housed Bavarian nobility and served as the seat of the German government before World War I. Audience members and musicians alike are dressed formally despite the structure’s decrepit condition.

That same month, Dresden staged a rubble performance of its own. The city had been destroyed by a firestorm in February 1945, ignited by American and British bombers, a catastrophe that claimed an estimated forty thousand lives. Now under Soviet jurisdiction, on August 4, 1945, in the ruins of the Kreuzkirche, director and composer Rudolf Mauersberger led the Kreuzchor in the first vesper service since the regime’s collapse. Eleven of the Kreuzchor’s boy choristers had perished in the firestorm, and Mauersberger chose the repertoire accordingly. Among the works the choir sang were the Renaissance motet, “Behold How the Righteous Dies” (Ecce, quomodo moritur Justus) by Jacobus Gallus Carniolus, “When Once I Must Depart” (Wenn ich einmal soll scheiden) from J. S. Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, and the Lutheran chorale “Eternal Sun of God” (Die güldene Sonne). To honor the firebombing victims, Mauersberger also composed two mourning motets, “You were like Us” (Ihr wart wie wir) and “How Desolate Lies the City” (Wie liegt die Stadt so wüst). Using passages from the Lamentations of Jeremiah as its text, the sparse harmonies of “How Desolate Lies the City” are reminiscent of Hugo Distler as well as the early polyphony of Heinrich Schütz, both composers whom Mauersberger greatly admired. The apocalyptic, poetic imagery speaks to the end of a city as well as to the end of the regime, survived by a narrator who recalls the terrible scene. As Martha Sprigge notes, the motet “was conceived harmonically, its voices crushed under the oppressive weight of destruction.”57 Mauersberger not only staged a ruin concert; he was also writing rubble music.

Figure 4.4. Grottenhof concert, 1945. Photograph by Tino Walz. Courtesy of Bildarchiv, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich.

Figure 4.5 Benefit concert, Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, Berlin, 1952. Courtesy of Süddeutsche Zeitung.

Although ruin concerts occurred throughout occupied Germany, they took place with greatest frequency in Berlin, beginning with Benda’s May 13 concert in the partially destroyed Schöneberg Rathaus.58 Concerts in Berlin ruins continued throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s, taking place in Dahlem, Mitte, Steglitz, and Charlottenburg. In 1947, the Bach Choir of Berlin’s Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church began staging a series of Bach cantatas in the ruins. The first performance was on Easter Sunday, featuring Christ lag in Todesbanden, BWV 4, in the rubble of the St. Matthäuskirche in Steglitz, and thereafter, the choir performed cantatas every two weeks in the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church. As one of the city’s most iconic bombed spaces, the church also hosted rubble performances to raise money for its reconstruction. In the photograph from a benefit concert (fig. 4.5), umbrellas block the sight lines of most audience members.59

Music, Ruins, and Film

The city’s ensembles returned to the rubble not only to make music for a contemporary audience; some of these performances were also staged for the camera, permanently capturing the destroyed temporality of the city. In 1950, the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra gathered in the ruins of their former concert hall to play Beethoven’s Egmont Overture. The performance, filmed as part of a documentary about the ensemble, Ambassadors of Music (Botschafter der Musik), featured the orchestra sitting on the sunken rubble of their former stage, aestheticizing, and in many ways romanticizing, the bombed hall on Bernburger Straße. Even conductor Sergiu Celibidache’s podium was stylized to appear as though it was emerging from a crater. The film turns the notion of rubble music on its head; now we are the only audience sitting alone with the musicians (fig. 4.6).

In a style owing much to film noir, director Hermann Stöß presents a highly edited version of the ensemble’s performance history. Ambassadors of Music was ostensibly about the orchestra’s role as messengers of goodwill, and the film emphasizes the positive to completely omit the negative—that is, the ensemble’s recent years of National Socialist patronage. Originally planned as a short film, Stöß decided he had enough material to expand his documentary to a full-length showcase, featuring preexisting footage of Furtwängler and Bruno Walter as well as new scenes with Celibidache. The city’s Department of Finance, Business, and Education agreed to support Ambassadors of Music, giving Stöß 75,000 DM to complete the project, as “the film will use rich archival materials to give a comprehensive account of the past and present meaning of the Philharmonic orchestra for Berlin’s cultural life.”60 Yet both Furtwängler and Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt would disagree with the department’s assessment. After viewing the film privately, Furtwängler was so angry over the director’s fictionalized portrait that he demanded to see the script, while Stuckenschmidt concluded the entire effort was a waste given the film’s inaccuracies.61

Figure 4.6. Celibidache and the Berlin Philharmonic in the ruins of the Alte Philharmonie, 1950. From Ambassadors of Music, dir. Hermann Stöß.

The most egregious misrepresentations in the film include Stöß’s use of propaganda footage from Philharmonic concerts in occupied and war-torn Europe. As Hans Knappertsbusch conducts the orchestra in plush locales such as Granada’s Alhambra and the Paris Opera House, Stöß depicts the ensemble as spreading the life-affirming message of music throughout the world. The attentive (captive?) audience listens closely. While the orchestra’s 1943 propaganda tour actually featured Beethoven symphonies, Ambassadors of Music replaces the audio track with other Philharmonic recordings. Stöß’s film depicts the ensemble performing Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique Symphony in Granada and Debussy’s Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun in Paris to reflect a more cosmopolitan worldview. The propaganda footage is now a palimpsest for music’s universal, rather than strictly German, qualities.

Central to the film are a series of ruin scenes in the ensemble’s destroyed concert hall. The sequence begins with concertmaster Siegfried Borries playing Beethoven’s Romanze, op. 40, presumably accompanied by the Philharmonic, whose music we can hear but not see. The camera alternates between tight shots of Borries’s face to panoramas of the hall’s interior. The viewer has the eerie sensation of being alone with the violinist amid a sea of ruins and ashes. After the Romanze, Stöß pans out to reveal the orchestra is also sitting in the rubble, arranged as if on their former stage. The ensemble performs the Egmont Overture, a work with a delicate political subtext about occupation and resistance. Beethoven wrote the overture in 1810 to accompany Goethe’s tragedy about the sixteenth-century Netherlandic count. The Spanish Habsburgs eventually beheaded Egmont for resisting their occupation, making him a martyr for Holland’s sovereignty. As Michael P. Steinberg notes, the Nazis revered the Egmont Overture, hearing in Beethoven’s composition “the musical correlative of the kind of heroism they wished to extol.”62 In 1945, American cultural officers even banned performances of Goethe’s Egmont, fearing its “opposition to foreign occupation forces”63 might encourage a German uprising.

The Egmont scene alternates between interior shots of the bombed shell to close-ups of Celibidache’s face engaged in the epic struggle required to play Beethoven’s music in the ruins. Stuckenschmidt described the conductor’s performance as “possessed.”64 Although the ensemble is arranged as if the stage is still standing, the back wall is missing, and we can see past the musicians to the ruined city beyond. The orchestra’s performance is trapped in aspic, and only we, as contemporary viewers, notice anything awry. There is something highly unsettling about these musicians returning to the site of the Philharmonic, dressed in tuxedos, to reenact a scene that never occurred in the first place. Celibidache never conducted the ensemble before or during the war, nor had he ever performed in the Bernburger Straße venue. By revisiting their hall six years after its bombing, the orchestra raised questions concerning their own victimhood and complicity. Aerial attacks had killed four Philharmonic members, and four more musicians lost their lives during the Soviet invasion. Only by returning to the ruined monumentality that was once their concert hall could the group shed their image as a propaganda orchestra, reclaiming Beethoven from the rubble by carefully staging their own suffering.

Still other postwar films with wider distribution made use of music and ruins to explore notions of German victimhood and suffering. As Robert Shandley writes, these films use the ruins “as a background and metaphor of the destruction of [the] German’s own sense of themselves,”65 as the subject matter drew contributions from both German and foreign directors. A central scene of Roberto Rossellini’s Germany, Year Zero (1948) features a phonograph recording of Hitler’s voice ringing through the desolate rubble. The film’s twelve-year-old protagonist, Edmund, sells the device to Allied soldiers who have literally and figuratively inherited the aftermath of fascism. At the film’s conclusion, after Edmund poisons his invalid father, he wonders alone through the ruins when music of a church organ interrupts his amblings. Rossellini blurs the distinction between diegetic and nondiegetic for a moment, until he cuts to shots of an organist playing in the rubble of a church (fig. 4.7). The chorale chords, vaguely reminiscent of Bach, emanate from the bombed shell, stopping passersby in their tracks (fig. 4.8). After pausing for a moment to listen, Edmund continues on, climbing into a ruined apartment building and jumping to his death. The church organ scene suddenly takes on new meaning as a benediction for his short life.

In Billy Wilder’s A Foreign Affair (1948), music and ruins suggest an altogether different form of victimhood—namely, that the occupiers themselves are the victims of German deceit, as Wilder’s film pokes fun at both the denazification and fraternization processes. The Americans look rather buffoonish for most of the film, unable to catch a former high-ranking Gestapo agent who is hiding in their sector. Hoping that he will resurface at a show of his former lover, cabaret singer Erika von Schlütow (played by Marlene Dietrich), the occupiers permit her to continue performing. But as Erika sings “The Ruins of Berlin,” written by Friederich Hollaender, himself a German Jewish exile who makes a cameo in the film as Erika’s accompanist, it is clear that the musical ruins in A Foreign Affair are not only traumatic remnants. The song’s lyrics, written in four languages as a nod to each of the occupiers, show that the ruins are alive and teeming with intrigue, dry humor, and the city’s infamous Berliner Schnauze.

The postwar proliferation of filmic ruins stands in contrast to movies of the Nazi era, where urban destruction rarely appeared onscreen. Instead, the ruined body symbolized the sacrifices of the people’s community. In the brief 1942 documentary depicting the Berlin Philharmonic’s birthday concert for the führer, close-ups of audience members form a significant part of the footage. Soldiers in uniform are among those prominently featured, and their injuries and eye patches are on prominent display as Furtwängler conducts Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony for a packed house. At the fourth movement’s conclusion, the orchestra’s dramatically descending thirty-second notes coincide with the image of two wounded soldiers sitting in a box, gauze bandages covering one’s nose and the other’s cheek. The chorus proclaims for the final time “Freude, schöner Götterfunken! Götterfunken!” (“Joy, beautiful spark of divinity!”), and the audience bursts into applause. Similarly, at the end of The Great Love (the most commercially successful film of the Nazi era), injured Luftwaffe pilot Paul Wendlandt convalesces in a beautiful alpine spa town, where, sunning himself on a terrace, he is reunited with singer Hanna Holberg (played by Zarah Leander). Hanna’s voice and presence heal all, validating Paul’s sacrifice for the national community. These staged displays of emotion are difficult to reconcile with our postwar sensibilities. The German ruined body was but one form of destruction; the Nazi regime, however, would eventually annihilate entire peoples and cultures.

Figure 4.7. The organist plays a chorale without a congregation. Germany, Year Zero (1:05:39).

Figure 4.8. Edmund and passersby pause to listen to the music. Germany, Year Zero (1:05:49).

Jewish Ruins

Ruin music making was not strictly a German gentile phenomenon. Jewish ruins, typically synagogues, also hosted performances and religious services in 1945. As Eric Langenbacher writes, “Memory is contested and almost always previously or potentially occupied terrain.”66 In Berlin, the terrain was occupied not only by the Germans but also by the four Allied powers and Jewish survivors. The city was a teeming hub for the displaced Jews of Europe, most of whom were living in one of the city’s three displaced persons camps: the American sector’s Mariendorf Bialik-Center and Düppel-Center at Schlachtensee, or a smaller, French-controlled Wittenau camp. The Düppel-Center was the largest, and by September 1946, it was home to just over five thousand Jewish refugees, most of whom were from Eastern Europe. These Allied-administered camps, and those like them across postwar Germany, functioned as essential waiting rooms until the displaced could secure permission to emigrate, typically to the United States, Palestine, Canada, or South Africa. After giving a July 1945 concert with Benjamin Britten for displaced persons at Bergen-Belsen, violinist Yehudi Menuhin called the camp “the saddest ruins of the Third Reich.”67 Even the Hebrew term that the survivors adopted for themselves, She’erith Hapletah (surviving remnant), gestured toward the fractured landscape. For some refugees, their experience in displaced person camps would last longer than their Nazi internment, as the last camp did not close until 1952.

Aside from Jewish refugees who were passing through the city, Berlin’s surviving Jewish community (Jüdische Gemeinde) began talks in May 1945 to discuss their future prospects. Founded in 1829, the community had 160,564 registered Jewish civilians in 1933; by 1945, that number hovered around 7,000, still the largest number of Jews anywhere in postwar Europe.68 Religious services for survivors and refugees began on May 11, 1945, led by Rabbi Martin Riesenburger at the vandalized Weißensee Jewish cemetery. Carefully placing new glass in the small synagogue adjacent to the cemetery, Riesenburger gave a short sermon as “tears and sobbing filled the room.”69 Most of those present were Jews who had spent the war years hiding in Berlin or living under assumed names. For Riesenburger, the service was about not only who was present but also who had perished in the intervening years. Heinz Galinski, another leading figure in the reconstitution of the Jüdische Gemeinde and the organization’s leader between 1949 and 1992, returned from Bergen-Belsen to find the Jewish community “consisted only of rubble.”70

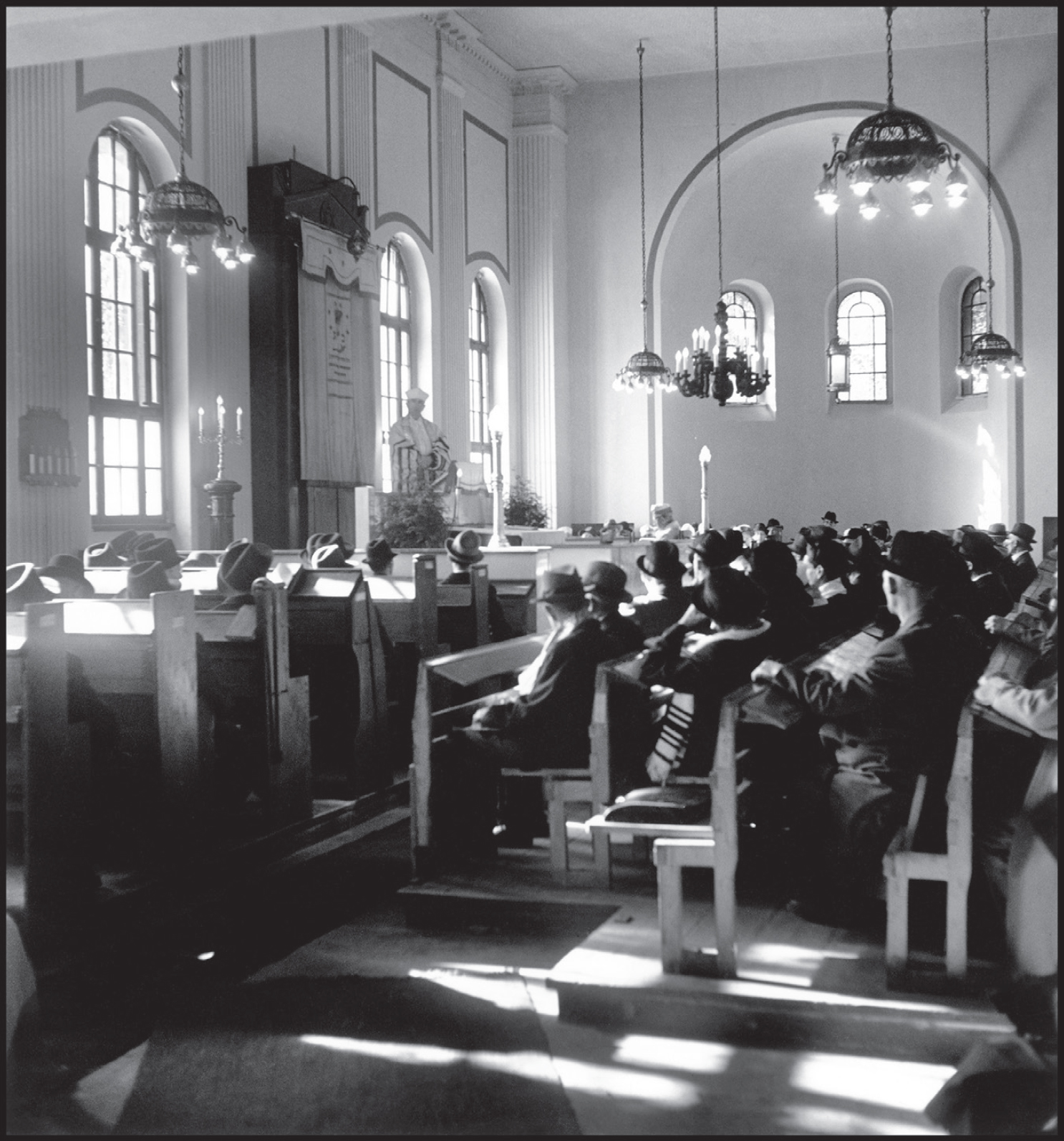

Six synagogues across Berlin reopened during summer 1945. The first memorial service expressly for the victims of fascism took place in the ruins of Berlin’s Pestalozzistrasse Synagogue, in the British sector, in July.71 That same month at the Rykestrasse Synagogue in Soviet-controlled Prenzlauer Berg, services resumed despite the lack of benches and smashed windows, spearheaded by Erich Nehlhans, the first postwar president of Berlin’s Jüdische Gemeinde. The Fraenkelufer Synagogue in the American sector of Kreuzberg reopened with a Rosh Hashanah sundown service on September 7. Photographer Robert Capa was on hand to document the event (fig. 4.9). His photographs show the hard work of the American troops who had repaired structural damage. Even though the walls appear freshly repainted and windows intact, the gaunt look of the worshippers betray their recent traumas. The accompanying article asserts that the survivor audience, exclusively male, were “all over 45-years-old,” though it was much more plausible that horrific conditions in the camps prematurely aged the attendees.72 Less formal events honoring Jews in Germany took place across the occupied country. Jewish American soldiers visiting Worms made their way to the destroyed synagogue, where they sang liturgical music.73

Figure 4.9. Rosh Hashanah service, Fraenkelufer Synagogue, Berlin 1945. © Robert Capa/Magnum Photos.

Using Jewish ruins for services and performances held rich symbolic meaning, though these events left radically different resonances than their counterparts for German civilians. In a city like Berlin, where Jewish life had not been confined or restricted to one district or quarter, the community returned to spaces alongside German, non-Jewish civilians, fully integrated into the ruined landscape of the capital. Furthermore, the ruined churches and rubbled synagogues held radically divergent meanings. Churches throughout the country, typically located in old town city centers and towering above other timber-framed buildings, were frequent targets for Allied bombers. Jewish sites, however, such as the Fraenkelufer and Rykestrasse Synagogues, had been the targets of state-sponsored violence, not collateral damage of the air war. After the war’s end, performing in these Jewish remnants asserted the community’s survival despite Nazi persecution.

Even though the synagogue services and concerts were certainly acts of resilience, the ground on which they took place no longer belonged to the city’s Jewish community. As Atina Grossmann and Michael Meng have noted, there were numerous difficulties facing Jewish organizations and individuals who wanted to reclaim their prewar property amid postwar hostility. The four Allies had separate policies on restitution, and navigating these rules and restrictions proved difficult for many. In the west, policies generally favored returning the properties to survivors. But without the large congregations many of these spaces had been designed for, the Jewish community sometimes decided to sell their property. In the east, these debates were avoided, and even suppressed, because the Communists took ownership of all property, whether formerly owned by Jewish citizens or not. In 1945, Erich Nehlhans complained to Soviet authorities about their treatment of Jewish property, noting that the Weißensee Cemetery was being used as a horse stable. In the end, it was often local German government officials, and not Jewish leaders, who decided the fate of postwar Jewish ruins.74

Despite a proliferation of Jewish ruin events in 1945, by the late 1940s, these stagings were largely a thing of the past. There are several reasons why this might have been—namely, many survivors and displaced had been granted permission to emigrate. Second, as reconstruction efforts continued, Jewish ruins were often built over to accommodate the demands of the German population. The synagogue on Berlin’s Passauer Street was torn down to make way for KaDeWe’s parking garage, while other religious sites became the grounds for the modern apartment complexes of the Wirtschaftswunder.75 As Michael Meng noted of the destroyed synagogue, “Berliners did not perceive it as a valuable ruin that had to be saved; they saw it as rubble that could be erased for the building of something better.”76 For many Germans, Jewish rubble conveyed the accusations and unprocessed guilt of the Holocaust, while destroyed German spaces symbolized civilian sacrifice and victimhood. Consequently, the stagings of German and Jewish ruin landscapes could not easily coexist, and ruined Jewish spaces were more often than not subsumed under the mantle of German postwar reconstruction.

Conclusions

If Jewish ruin concerts represented continuity, resilience, and survival, German performances emphasized a kind of aestheticized victimhood, staging the rubble sublime. By using the ruins to give concerts, German musicians were among the first group of artists to interrogate, exploit, and delight in staging the destruction for their own purposes. What could draw attention more clearly to the air war’s toll than to play among, around, and inside the rubble? In both East and West Berlin and across occupied Germany, ruin concerts were erected as a kind of sonic memorial to German victims—not to victims of the Germans. As historian Toby Thacker notes, “Photographs of pensive listeners in shattered buildings listening to Beethoven have taken on an iconic status in representations of post-war German cultural history.”77 And yet, was there not something macabre about these performances, with musicians and audience members alike reveling in their own wretchedness? As Sebald unequivocally notes of postwar concertgoers, “We may also wonder whether their breasts did not swell with perverse pride to think that no one in human history had ever played such overwhelming tunes or endured such suffering as the Germans.”78 It was no coincidence that concerts in the ruins almost exclusively featured German composers, not music the Nazis banned on religious or political grounds. It was Beethoven, and not Mendelssohn, whose music formed a counterpoint to the destruction.

The deliberate choice to play in bombed shells was rendered all the more dramatic considering there were other places in which German ensembles could and did perform, such as movie theaters and surviving concert halls. Ensembles (and audiences, for that matter) made the decision to play in partially and completely destroyed venues because they did not have to concede these spaces to the Allies. The occupiers did not requisition ruins for military use. None of the victors wanted them, for the ruins belonged solely to the Germans.

Ruin performances enabled German ensembles to engage with victimhood and suffering despite Allied reeducation efforts. By revisiting sites destroyed by the air war—namely halls and churches that were once symbols of great national pride—musicians recast the traumatic experiences of wartime bombing into a postwar commentary of survival. In Munich, Nuremberg, Dresden, and Berlin, instrumentalists returned to sites loaded with prewar meaning. Musicalizing in the ruins meant ensembles could show the devastating toll of the air war while avoiding more difficult questions of complicity and guilt.

Ruin concerts persisted well after Nazi Germany’s surrender, firmly etched in German cultural memory. In July 2015, Nuremberg’s Teacher Choral Association and the Nuremberg Symphony staged a performance of The Creation to commemorate the seventieth anniversary of the war’s end. The purple poster advertising the concert featured a sketch of the ruined St. Sebald as its background. Similarly, each February 13 in Dresden, performances of Mauersberger’s Dresdner Requiem commemorate the city’s firebombing.79 The entrance of Berlin’s Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church has been left a ruin, though a new church to host services and concerts was built on the ruins in 1963. The vicissitudes of the postwar period can be heard in these performances, containing the remnants, both musical and physical, of the Allied air war.

Notes

1. Henry Gluski, telephone interview by the author, July 1, 2010.

2. Monica Black, Death in Berlin: From Weimar to Divided Germany (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 180.

3. George Clare, Before the Wall: Berlin Days, 1946–1948 (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1990), 18. See also R. Murray Schafer, “The Music of the Environment,” in Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music, ed. Christoph Cox and Daniel Werner (New York: Bloomsbury, 2017), 36; and Georgina Born, ed., Music, Sound, and Space: Transformations of Public and Private Experience (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 24–31.

4. Richard Brett-Smith, Berlin ’45: The Grey City (London: Macmillan, 1967), 107.

5. Georgina Born, “Afterword: Music Policy, Aesthetic and Social Difference,” in Rock and Popular Music, ed. Tony Bennett, Simon Frith, and Lawrence Grossberg (London: Routledge, 1993), 266–92.

6. Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1983), 149.

7. Adolph Hitler, Manual of the German Radio, 1938–39, quoted in Schafer, “The Music of the Environment,” 37. See also Christopher Hailey, “Rethinking Sound: Music and Radio in Weimar Germany,” in Music and Performance during the Weimar Republic, ed. Bryan Gilliam (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 13–36; and Andrew Oster, “Rubble, Radio, and Reconstruction: The Genre of Funkoper in Postwar Occupied Germany and the Federal Republic, 1946–1957” (PhD diss., Princeton University, 2010), 1–35.

8. For more on Heldengedenktag celebrations, see Black, Death in Berlin, 101, and for more information about the Request Concert radio program and film, see Marc Silberman, German Cinema: Texts in Context (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1995), 66–80; Brian Currid, A National Acoustics: Music and Mass Publicity in Weimar and Nazi Germany (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 54–58; Peter Fritzsche, Life and Death in the Third Reich (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2008), 71–75; Nanny Drechsler, Die Funktion der Musik im deutschen Rundfunk, 1933–1945 (Pfaffenweiler: Centaurus-Verlagsgesellschaft, 1988), 131–34; and Heinz Goedecke and Wilhelm Krug, eds. (1942) 2002, Wunschkonzerte für die Wehrmacht. Reprint, Emmelshausen: Condo, 122.

9. Joseph Goebbels, Tagebücher von Joseph Goebbels, Teil II, Diktate 1941–1945, vol. 15, ed. Maximilian Gschaid (Munich: K. G. Saur Verlag, 1995), 180.

10. Annegret Fauser, Sounds of War: Music in the United States during World War II (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 9.

11. Dietmar Arnold and Reiner Janick, Sirenen und gepackte Koffer: Bunkeralltag in Berlin (Berlin: Ch. Links, 2003), 13. Concerning the Kuckuck-Ruf and stages of an air raid, see Jörg Friedrich, The Fire: The Bombing of Germany, trans. Allison Brown (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006), 328; and Horst Götsch, “Man konnte die Bomben zählen,” in Wie Silberfische flimmerten Bomber am Himmel: Erinnerungen an das Inferno des Krieges in Berlin-Lichtenberg, 1940–1945, ed. Christine Steer and Dietmar Arnold (Berlin: Edition Berliner Unterwelten, 2004), 48–51. For an account of radio listening in a bunker, see Helmut Altner, Berlin Dance of Death, trans. Tony Le Tissier (Havertown, PA: Casemate, 2002), 126.

12. Quoted in Carolyn Birdsall, Nazi Soundscapes: Sound, Technology and Urban Space in Germany, 1933–1945 (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2012), 11. Around 250 cases where an individual listened to a foreign radio station resulted in a death sentence. These individuals were punished so severely because they had passed along the information they obtained to a third party. For more, see Birdsall, Nazi Soundscapes, 131–39; Currid, A National Acoustics, 49; Hailey, “Rethinking Sound,” in Gilliam, Music and Performance, 13–14; Oster, “Rubble, Radio, and Reconstruction,” 59; and Erik Levi, Music in the Third Reich (New York: St. Martin’s, 1994), 124.

13. The quotations are from Currid, A National Acoustics, 1; Joseph Sauer quoted in Friedrich, The Fire, 266, and Brett-Smith, Berlin ’45, 75, respectively. For more on radio and Hitler’s death, see Esteban Buch, Beethoven’s Ninth: A Political History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 219.

14. Radio Usage Report, February 17, 1947, RG 260, Box 34, Radio Control, Radio Policy File (1945–1949), NARA II; and Gerth-Wolfgang Baruch, “Der deutsche Rundfunk,” Melos, January 1947, 69–72. Radio Luxembourg served as the main US propaganda station from September 1944 until November 1945, before the creation of stations throughout Germany. Larry Hartenian, Controlling Information in U.S. Occupied Germany, 1945–49: Media and Manipulation and Propaganda (Lewistown, NY: Edwin Mellen, 2003), 52–54; Gesa Kordes, “Darmstadt, Postwar Experimentation, and the West German Search for a New Musical Identity,” in Pamela Potter and Celia Applegate, eds., Music and German National Identity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 212; and Florian Weiß, Sedjro Mensah, and Thomas P. Strauss, The Link with Home—And the Germans Listened In: The Radio Stations of the Western Powers from 1945 to 1994 (Berlin: Ruksaldruck, 2001), 10.

15. Paddy Scannell and David Cardiff, A Social History of British Broadcasting, 1922–1939: Serving the Nation (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1991), xiii.

16. Josephine Dolan, “The Voice That Cannot Be Heard: Radio/Broadcasting and the ‘Archive,’” The Radio Journal 1, no. 1 (2003): 71.

17. Jonathan Sterne, The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), 13.

18. Michael Bohnen, “Bericht über den Aufbau der Städtischen Oper in der Zeit vom 1.Mai 1945 bis 30. April 1946,” May 6, 1946, C Rep. 120, Nr. 1484, Landesarchiv; “Hört den Rundfunksender Berlin,” Tägliche Rundschau, May 20, 1945; “Hier spricht Berlin,” Tägliche Rundschau, May 27, 1945; and Toby Thacker, Music after Hitler, 1945–1955 (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2007), 34. The British would later fine Ludwig 10,000 DM in lieu of an 18-month jail term for failing to declare his Nazi Party membership.

19. Rundfunk Programme vom 23. Mai 1945 bis 5. Februar 1946, Deutsches Rundfunk Archiv, Potsdam, Germany; and Baruch, “Der deutsche Rundfunk,” 69–72.

20. Ribbentrop was tried at Nuremberg and executed for war crimes in 1946. Weiß, Mensah, and Strauss, The Link with Home, 25–26.

21. Charles S. Lewis, “Music Programming,” August 23, 1946, RG 260, Box 134, Records of the Information Control Division: Central Decimal File of the Executive Office, 1944–49, NARA II. When the DIAS first aired, it was broadcast by Drahtfunk, a wired radio service that Berliners could get when they attached their telephone wires to a radio set. Drahtfunk broadcasting is of a poorer quality than Rundfunk. For more on DIAS, see Donald Roger Browne, “The History and Programming Policies of RIAS: Radio in the American Sector (of Berlin)” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 1961), viii, 355; and Hartenian, Controlling Information in U.S. Occupied Germany, 54.

22. Browne, “The History and Programming Policies of RIAS,” 227.

23. The RIAS Symphony Orchestra became the German Symphony Orchestra in 1993. Amy C. Beal, “The Army, the Airwaves, and the Avant-Garde: American Classical Music in Postwar West Germany,” American Music 21, no. 4 (Winter 2003): 485–86; H. W. Heinsheimer, “Musik im amerikanischen Rundfunk,” Melos 14, no. 12 (October 1947): 332–35.

24. “6871st District Information Services Control Command: Newsletter,” August 28, 1945, Records of the Information Control Division: Records of Information Services Division Staff Advisor, 1945–49, RG 260, Box 63, NARA II. For more on reeducation, see Toby Thacker, “Playing Beethoven like an Indian,” in The Postwar Challenge: Cultural, Social, and Political Change in Western Europe, 1945–58, ed. Dominick Geppert (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 369–71; and Alex Ross, The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007), 349. On Taylor’s role in postwar Germany, see David Monod, Settling Scores: German Music, Denazification, and the Americans, 1945–1953 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 18, 22; and Davidson Taylor, “We Are All Grateful,” May 23, 1945, RG 260, Box 237, Records of the Education and Cultural Affairs Division: Records Relating to Music and Theater, NARA II.

25. Radio Usage Report, February 17, 1947, RG 260, Box 34, Radio Control, Radio Policy File (1945–1949), NARA II.

26. The quotations are from “Draft Guidance on the Control of Music,” June 8, 1945, RG 260, Box 134, Records of the Information Control Division: Central Decimal File of the Executive Office, 1944–49, NARA II.

27. Quoted in Michael Kater, The Twisted Muse: Musicians and Their Music in the Third Reich (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 178. While the War Department suspected Hindemith had been more compliant with the Nazi regime than he admitted, music officers were unaware of this fact. Monod, Settling Scores, 115–26.

28. For more on twelve-tone music in Nazi Germany, see Joan Evans, “Stravinsky’s Music in Hitler’s Germany,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 56 (Fall 2003): 525–94; Michael Kater, Composers of the Nazi Era: Eight Portraits (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 31–56, 111–43; Kater, The Twisted Muse, 73, 177–241; Levi, Music in the Third Reich, 92, 112–13. After surviving the war, Webern had the misfortune of being shot by an intoxicated American Army cook who mistakenly believed the composer was trying to foil his lucrative black market deal. For more details surrounding Webern’s death, see Hans Moldenhauer, The Death of Anton Webern: A Drama in Documents (New York: Philosophical Library, 1961); Hans Moldenhauer, “Webern’s Death,” Musical Times 111, no. 1531 (September 1970): 877–81; and Ross, The Rest Is Noise, 348–52.

29. Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt, Zum Hören geboren: Ein Leben mit der Musik unserer Zeit (Munich: Deutscher Taschen Verlag, 1982), 141.

30. Cultural officers in all media fields relied a great deal upon political reliable German civilians, for, as ICD Chief Robert McClure noted, “it is believed that the outward and visible aspects of the work should be entrusted entirely to Germans of proper background and qualifications.” McClure, “Suggested Information Control Program for the Reorientation of German Youth,” August 22, 1945, Records of the Information Control Division: Central Decimal File of the Executive Office, 1944–49. RG 260, Box 134. NARA II. For more on Stuckenschmidt’s work, see Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt, “Vorträge in Attichy, Mai-July 1945,” Folder 2444, Stuckenschmidt Papers, AdK. Stuckenschmidt was a prolific writer, and in addition to writing several books on twentieth–century music, he also authored texts on composers Blacher, Ravel, Schoenberg, and Stravinsky, among others. See Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt, Twentieth Century Music (London: World University, 1969); Stuckenschmidt, Boris Blacher (Berlin: Bote & Bock, 1985); Stuckenschmidt, Maurice Ravel: Variationen über Person und Werk (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1966); Stuckenschmidt, Schönberg: Leben, Umwelt, Werk (Zürich: Atlantis, 1974); and Stuckenschmidt, Strawinsky und sein Jahrhundert (Berlin: Piper, 1957).

31. “Erstes Gespräch zwischen Musiker und Musikfreund,” Studio für Neue Musik, September 3, 1946, Stuckenschmidt Papers, Folder 2571, AdK.

32. Ibid.

33. “Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, Gedenkwoche,” November 4, 1947, Folder: E-Musik, Musiksendungen, B 104-00-24, German Radio Archive, Potsdam, Germany.

34. Radio Usage Report, February 17, 1947, RG 260, Box 34, Radio Control, Radio Policy File (1945–1949), NARA II.

35. Nicolas Nabokov, “Boris Blacher,” in Boris Blacher, ed. Heribert Henrich and Thomas Eickhoff (Berlin: Fuldaer, 2003), 9. See also Thomas Eickhoff and Werner Grünzweig, “Gerty Herzog–Blacher im Gespräch,” in Boris Blacher, ed. Heribert Henrich and Thomas Eickhoff (Berlin: Fuldaer, 2003), 33, 66–69; and Stuckenschmidt, Boris Blacher, 29.

36. Mathias Lehmann, “Musik über den Holocaust,” in Das Unbehagen in der “dritten Generation”: Reflexionen des Holocausts, Antisemitismus und Nationalsozialismus, ed. Klaus Holz and Sven Wende (Muenster: Lit, 2004), 47–48; and Oster, “Rubble, Radio, and Reconstruction,” 12, 33, 141.

37. Dr. Wilhelm Hoffmann, “Die letzten Tage von Berlin,” Der Rundfunk 30, April 28–May 4, 1946. For more on Wilhelm Hoffmann, see Francis R. Nicosia, “Introduction: Resistance to National Socialism in the Work of Peter Hoffmann,” in Germans against Nazism: Nonconformity, Opposition and Resistance in the Third Reich, ed. Francis R. Nicosia and Lawrence D. Stokes (New York: Berghahn Books, 2015), 6–7.