1

Galileo’s Europe

In the Jubilee year of 1600, Galileo reached the midpoint of the eighteen years he regarded as the happiest of his life. These were the years he spent as professor of mathematics at the Venetian University at Padua, where expression was freer than elsewhere in Italy and the Roman Inquisition had little sway. Venice tolerated people who increased its wealth and welcomed well-to-do foreign students, including English Protestants, to its university. When at the end of the happy years Galileo had the misfortune to discover through his telescope stars and moons never before seen by any human being, his British students were prepared to defend his claims and to inform folks back home of the astonishing refashioning of the heavens above Padua.

Almost six years to the day after Galileo had published his Sidereus nuncius in March 1610, the cardinals of the Holy Roman Inquisition for the Suppression of Heretical Depravity decided that the Copernican system of the world, which Galileo believed his discoveries supported, was formally heretical because contrary to Scripture and, moreover, untenable in the Aristotelian physics to which the Christian worldview was wedded. To be precise, the cardinals found that the thesis of a stationary sun was formally heretical, that of a moving earth erroneous in faith, and both absurd in philosophy. Why the Roman Catholic Church thought it necessary to intervene in a dispute over cosmic geometry, and why it believed that it could do so effectively, take some explaining.

Resurgent Rome

The Roman Catholic Church had much to celebrate at its Jubilee in 1600. On the periphery of Europe, in Poland and Ruthenia, Jesuits were winning back Protestant souls. The King of Scotland, James VI, was intriguing for the throne of England and flirting with converting to Rome. His wife, Queen Anna, had already signed up. Beyond Europe, missionaries, Jesuit, Franciscan, Dominican, and Benedictine, successfully proselytized for the truth as they saw it. Strayed sheep—Nestorians, Copts, Maronites—had returned to the fold.1 International Protestantism was on the defensive, although it still held its own against Spain in the Netherlands. In France, it enjoyed a measure of toleration under the Edict of Nantes (1598), and in Venice, whose nobles declined to celebrate the Jubilee, it may have had more friends in high places than the ruler of Rome. “[A]ll the world knows [the Venetians] care not Three-pence for the Pope.”2

The division of Christian Europe between the Protestant northern German states, Scotland, England, Switzerland, and the Scandinavian countries, on the one hand, and Catholic Austria, Bavaria, Poland, Italy, Spain, and Portugal, on the other, would not change much, despite the hot spots where the two blocks rubbed together. This was the insight of Edwin Sandys, a risk-prone Oxford graduate, who acquired his objectivity by investigative travel, three years of it, in Germany, Italy, France, and Geneva. Sandys praised the Catholic Church for its training of priests, charitable institutions, and uniformity of doctrine, and excused its censorship, inquisition, confession, and ostentation as useful means of social control. On this criterion he could regard the pope, Clement VIII, as a “good Man, good Prelate, and good Prince.” Where the Catholics did well, as in organization and uniformity of doctrine, the Protestants, with their splits and wrangles, scored poorly. Sandys reckoned the Anglican Church the best of the lot for its compromise between reform and tradition and dreamt that English practice might serve as “an umpire and also as a director” for bringing Christendom together again. Many of our actors, including King James, shared this dream, with the reservation that popes and Jesuits had no part in it. In short, like many of his countrymen, but unlike his puritanical father, a former Archbishop of York, Sandys could tolerate the Catholic faith but not the Roman Church.3 His book, A Relation of the State of Europe (1605), would become a weapon in the hands of Galileo’s friends.

The popes had a more formidable armory. Besides Spanish and Austrian arms and money, they had new institutions and doctrines to combat the heresies of Luther and Calvin. These instruments included the Society of Jesus, formed in 1540 primarily to succor the poor, but grown by 1600 into the schoolmasters of Catholic Europe and the most disciplined and dangerous agents of their own and papal policy; the Roman Inquisition (the Holy Office), formed in 1542 to extirpate heresy within the church; the Roman Index of Prohibited Books (1557–9), appointed to ensure wholesome reading matter; and the Council of Trent (1545–63), assembled to outfit Catholics for battle with heretics. The council issued decrees on discipline and doctrine that created better educated priests, more responsible bishops, greater uniformity of dogma, and a more aggressive Papacy, and thereby insured the permanent division of Christendom.

One of Trent’s reforms defined and controlled the distribution of indulgences, or remissions of penalties for sins. The council abolished their sale, which had pushed Luther to rebellion, while upholding their value.4 Securing them was the main purpose of the pilgrims who came to Clement’s jubilee by the hundreds of thousands, 1.2 million or perhaps 3 million in all, in a tremendous demonstration of the reach and power of the Catholic faith.5 Pilgrims obtained their indulgences most readily and reliably through an innovation intended to symbolize resurgent Rome. By visiting the basilicas of S. Pietro, S. Paolo, S. Giovanni in Laterano, and Santa Maria Maggiore fifteen times in any order and proper contrition, they would receive a plenary indulgence for past trespasses. A pilgrim lucky enough to drop dead immediately after completing the course would be nearly as sinless as a freshly baptized babe. Clement expanded easy opportunities for indulgence by enrolling the four obelisks planted in front of the basilicas a decade earlier. Whoever knelt at any of these symbols of Christian triumph over paganism and, while gazing at the cross surmounting it, prayed for “Holy Church and the Roman Pontiff,” would receive an indulgence of 10 years and 10 quarantines, which exact sinners will know sum to 4,052 days, including leap years.6

Among the pilgrims came a number of heretics, some to laugh at, others to flirt with, the old religion. Many of both kinds converted, drawn by their countrymen who had already gone over and urged along by accomplished proselytizers. Potential recruits might receive charitable treatment followed by a hard sell and, thus softened, joyfully join their benefactors. Physicians harvested many such souls from hospitals. The prize catch of 1600 was the grandnephew of the archfiend Calvin, who had come to mock, fell ill, abjured his errors, and joined the Capuchins.7 The English College in Rome, where Jesuits trained infantry for the spiritual reconquest of Britain, and its affiliated English Hospice, were particularly hazardous places.8 But there was danger everywhere. A case of consequence for our story, Tobie Matthew, survived a life-threatening illness only to succumb to Rome. Like Sandys, he was the liberated son of a puritanical Archbishop of York. His friends tried to return him to England and the true faith; but Matthew had been snared by the beautiful churches, good sermons, learned men (including Galileo), and “wholesome wines…excellent pictures…and choyce music” of Italy. He ignored his friends and became a priest.9

As if to remind the faithful that their nourishing Mother was hitched up to an authoritarian Papa, the Inquisition sent the impenitent monk Giordano Bruno to the stake before a throng of fascinated, horrified pilgrims during the second month of the Jubilee year. Bruno had traveled Europe, even unto Oxford, shocking Protestants and Catholics alike before the Inquisition caught up with him. It did not succeed in talking or torturing him out of such heresies as denying the divinity of Christ and expounding an animistic religion purer than Christianity. He co-opted Copernicus into the congregation of animists on the far-fetched ground that a moving earth implied a living one and claimed to be the first among Copernican exegetes. His views and fate helped to make Copernican ideas suspect and scary wherever the Inquisition impended. In England, in contrast, Bruno and Copernicus were regarded as more mad than menacing. In the influential opinion of George Abbot, a future Archbishop of Canterbury, “[Bruno] undertooke among other matters to set on foote the opinion of Copernicus, that the earth did goe round and the heavens did stand still; whereas in truth it was his owne head which rather did run round, and his braines did not stand still.”10

Anti-Roman Trio

The form of government that insured the longevity, prosperity, and relative tranquility of the Republic of Venice, and earned it the epithet of Serenissima, presented a problem to the early Stuarts. Standard political theory held that the security of a state required at least outward conformity in religious observance. Venice, however, prospered while allowing nonconformists to worship much as they pleased provided that they did not politic or proselytize. So thick were the English in Venice that the pope demanded that its Senate thin them.11 In vain. Venetian wealth depended on an import–export business conducted through middlemen of diverse religions who worshipped together at the shrine of Mammon. Equal application of the law stabilized the system. Or so English playgoers would conclude from the equation of trade and justice in The Merchant of Venice.

The [Doge] cannot deny the course of law

. . . . .

Since that the trade and profit of the City

Consisteth of all nations.12

The despised Jew Shylock expected the fair operation of the law to grant him the pound of flesh owed him by the merchant Antonio.

The Venetian constitution reserved executive offices in the state to patricians who elected the Doge from among the older and wiser members of their class by an elaborate semi-random procedure; and, as a further barrier to despotism, hedged the winner around with rules that made it difficult for him to accumulate power.13 Wealth and wisdom were the state’s hallmarks, and longevity their consequence. “Could any State on Earth Immortall be ǀ Venice by Her rare Government is She.”14 Ben Jonson’s Volpone enforced these characteristics by parody. The play is situated in Venice, where Sir Politic Would-Be has come to practice statecraft and his garrulous Lady (“The sun, the sea will sooner both stand still ǀ Than her eternal tongue”) to learn the style of its courtesans.15

Nothing could be further from dogeship than the concept of kingship that the future James I developed while only King of Scotland and wrote out in a manual for the benefit of his heir. This handbook, Basilikon doron (1599), or “Royal gift,” teaches that a prince and his dynasty hold office by appointment from God. A doge, elected by his peers and succeeded by another so chosen, was no real prince. Fear that they might be reduced to the status of a doge haunted the first Stuart kings. And rightly so, for that is just what happened to James’s son and heir Charles I.

According to James’s doctrine, a prince ruled absolutely, by divine appointment, within his domains. He extended the same status to the pope, whom he acknowledged as a divine-right ruler within the Papal States as well as the spiritual leader of the Roman Catholic Church. Over English Catholics the Pope had no temporal jurisdiction. When James succeeded Queen Elizabeth I, he claimed the power to regulate religion within his three kingdoms of Scotland, England, and Ireland. He would do so, popelike, through a hierarchy of bishops. They were the key to religious discipline and could be hard or soft on nonconformity as their commitments and the royal will required. The Stuarts believed that without their episcopate they would have no jurisdiction: “no bishop, no king,” as James liked to say. That, too, Charles proved to be correct.

The subjection of bishop to prince, of church to state, became a life or death matter for the Republic of Venice when, in 1606, an interdict imposed by Clement’s successor, Paul V, disturbed the tranquility of the Serenissima. Paul imposed the interdict, which prohibited clergy from marrying the quick and burying the dead, to force Venice to change policies limiting Rome’s rights to inherit land and protect clergy accused of crimes. The Senate ordered priests to continue their services and expelled those, like the Jesuits, who refused to obey. Its adoption of James’s view of church–state relations precipitated the equivalent of a constitutional crisis.16 Rome chose as its principal paladin in the resultant paper war the master controversialist Cardinal Robert Bellarmine, chief of the Jesuit theologians, deep, crafty, and learned. Against him the Republic fielded the smartest man in Europe, Fra Paolo Sarpi, of the placid Order of Servites. Among Sarpi’s friends was someone almost as smart as he, Galileo Galilei; and among his supporters was someone bolder than both, the Archbishop of Spalato, Marc’Antonio De Dominis. The three earned the sustained attention of the Roman authorities, which, in good time, killed the archbishop, imprisoned the mathematician, and tried to assassinate the monk. Most of the books of Sarpi and De Dominis made their way onto the Index, where Galileo’s Dialogue, the book in our picture, joined them. The crimes of these bravos were well known in England.

The Monk

Sarpi’s circle of friends included the English ambassador to Venice, Henry Wotton, who engaged him in a project to convert Venice to Protestantism. Sarpi’s theology was probably closer to Protestant than Catholic; his disdain of Paul V (“timid with equals, ungrateful to benefactors, supercilious with inferiors, and passionately fond of money”) was boundless; and he clung to the absolute sovereignty of the state as a bulwark against papal claims to supreme authority over Christian princes.17 The Venetian monk and the English ambassador therefore had a firm basis for collaboration. Since Venetian law prohibited foreign diplomats from dealing privately with state officials without permission, Wotton worked for his church and Sarpi’s conversion through several intermediaries, of whom the most important were Wotton’s chaplain William Bedell and Sarpi’s lieutenant Fra Fulgenzio Micanzio.18

The chaplain, a pious and upright man, frequented his friends’ monastery on the pretext of teaching them English. Their choice of textbook was Sandys’s Relation, which Bedell translated, Micanzio corrected, Sarpi annotated, and the Doge approved. Although ready for the press before 1610, the book and its anti-Roman annotations did not come out until after Sarpi’s death. Its editor then was Jean Diodati, a Calvinist from Geneva, famous for his translations of Scripture, who had collaborated with Wotton’s group to insinuate Protestantism into Venice.19 Chaplain Bedell’s discovery that the Roman numerals in the dedicatory phrase, pavlo v. vice-deo, found in Jesuit texts, sum to the Number of the Beast (dclvvvi = 666), no doubt encouraged them all.20

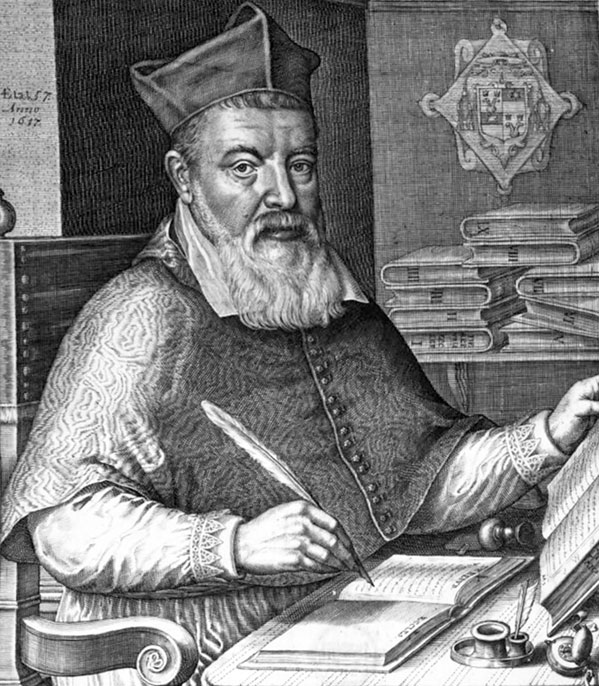

Knowing that a picture can be more persuasive than words, Wotton surreptitiously obtained Sarpi’s portrait and sent it overland to England to display the strength and quality of Venetian leadership. The Inquisition confiscated the talisman. Wotton promptly had a second portrait made, which carried an even stronger message, as it showed Sarpi with the patch he then wore to cover scars from the Vatican’s attempt to kill him.21 Wotton shipped the new portrait by a secure route and had it reproduced in England to give to friends who could appreciate its expression of fearless determination (Figure 7).22 Portraits have powers.

Figure 7 Unknown artist, Paolo Sarpi, “Eviscerator of the Council of Trent” (c.1610). The black patch covers a scar left by an incompetent assassin.

Meanwhile Micanzio was preaching openly against the Pope. The papal nuncio endeavored to shut him down. The Spanish ambassador complained to the Venetian Senate, which blithely replied that it could find nothing anti-Catholic in the sermons. The scandal rose to the attention of the kings of Spain and France, again to no avail, despite the rumor that Micanzio, Sarpi, and Wotton were promoting Protestantism with the help of a pastor from Geneva.23 Though the Vatican rated “Fra Paolo…a pure Calvinist [who] had only heretics, and leaders of heretics, as close friends,” the Republic protected him. In fact there was nothing to worry about. As Diodati came to recognize, Italians could not be saved. “Calvinist worship would seem too cold to such sensual natures.”24

Feigning Catholicism, promoting Protestantism, and championing the cause of Venice were the least of the sins the Vatican saw in Sarpi. The worst was his undermining of Roman Catholicism by his inspired use of that most powerful form of written persuasion, history. And of all his works of the kind, his History of the Council of Trent, an international bestseller despite its length, was the most devastating. A witty and withering account of the stuttering assemblies that set the foundations of the Catholic Counter Reformation, it threatened all received ecclesiastical history by approaching the council as the business of men rather than of the Holy Spirit. Earlier Church historians had irresponsibly invoked the will of God rather than the usual forces at work in human endeavors and ignored the objectives of the popes. Even the best of them had no concept of piety. Take Leo X, whose sale of indulgences precipitated Luther’s rebellion. He was a noble by birth, style, education, “marvellous sweet [in] manner,” of a “singular learning in humanity.” “And he would have been a Pope absolutely compleate, if with these he had joyned some knowledge in things that concerne Religion.”25

Wotton read an incomplete draft of Sarpi’s Trent, recognized its value as propaganda as well as science, and advertised it widely after returning to England in 1611. King James thought it so important that he directed Dudley Carleton, who had replaced Wotton as ambassador in Venice in 1610, to invite Sarpi (“a sound Protestant, as yet in the habit of a friar”26) to England to finish it free from the dangers and harassment that bedeviled him in Italy. Fra Paolo preferred to stay in Venice. Carleton pressed him to finish the great work and offered, as the competition to beat, a book by his godly relative George Carleton, The Consensus of the Catholic Church against the Men of Trent (1613). Sarpi thought Carleton’s Consensus far too indulgent of Roman arrogance and blunders.27 Still he hesitated. Publication would offend many good Catholics and probably expose him to new dangers.

When Archbishop Abbot learned about Sarpi’s manuscript history, he resolved that so useful a piece of anti-papal propaganda should not remain in a monastery. He commissioned Nathaniel Brent, a bold Italophile whose travels had aroused the interest of the Inquisition, to return to Venice and acquire the manuscript. Brent was a friend of Daniel Nijs, a Calvinist merchant of Venice, who dealt in luxury goods and intelligence, and sometimes acted as intermediary between Wotton’s embassy and Sarpi’s monastery.28 Brent soon obtained a copy of the immense manuscript. With the help of Nijs’s network, it found its way to Abbot between June and September 1618. It arrived in 197 canzoni (songs), as the archbishop called them to put bloodhounds off the scent. Their tune was to his taste. “She is an excellent musician that frameth them.”29 The combined power of church and state, of Abbot and James, decreed their immediate publication in Italian. The editorial work fell to the Dean of Windsor.

The Maverick

The dean was none other than De Dominis, who, unlike Sarpi, had accepted James’s invitation and fled to England. This was his third refashioning. He began his career as lecturer in mathematics at the Jesuit College in Padua, where he would have competed for students with Galileo had the Venetian Senate not prohibited the college from teaching university subjects. He soon quit mathematics and the Jesuits to join the Church’s moneymaking officialdom. The business of his archdiocese, Spalato, brought him often to Venice, where he fell in with Sarpi, Micanzio, Wotton, Bedell, and Galileo. Wotton rated him a “person…of singular gravity and knowledge,” and Micanzio, who knew him well, could report nothing more defamatory about him than being in love with the books he had written (Figure 8).30

Figure 8 Marc’Antonio de Dominis among his books, from the frontispiece to his Republica ecclesiastica, i (1617).

One of these defended King James’s Premonition to all Christian Monarchies, Free Princes and States (1609), which instructed the Vatican about the Oath of Allegiance required of English Catholics after the Gunpowder Plot of 1605.31 The oath did not touch religious belief, James wrote, and agreed perfectly with the true teachings of the Roman Church.32 He continued his Premonition in this irenic manner, itemizing common ground between Catholicism and Protestantism before accusing Paul V of countenancing assassination, sorcery, and fornication. A strange way to seek accommodation! An astrological analogy clarified James’s methods: “[Catholics] look upon his Majesties Bookes, as men look upon Blasing-Starres, with amazement, fearing that they portend some strange thing, and bring with them a certain Influence to worke great change and alteration in the world.”33 The Vatican prohibited Catholic rulers from receiving James’s celestial message. Most obeyed. Henry IV of France, the only sovereign to accept it, observed in doing so that kings should not write books.34

It fell to Wotton to present the unwanted Premonition, bound in gold and crimson velvet, to the Republic of Venice. Its senators accepted the book with perfect courtesy and exquisite dissimulation: they feigned ignorance of its contents, thanked James profusely, and archived it without opening it. The Venetian Inquisition then read and banned it. Wotton expressed great outrage at this insult to his sovereign and withdrew his embassy without mentioning that he, Bedell, and Sarpi had translated the Premonition to encourage anti-Roman Italians, or that their friend, the Archbishop of Spalato, who was scarcely inferior as a controversialist to the Roman gold standard Bellarmine, was writing in favor of King James.35

De Dominis arrived in England in December 1616 after a stop at the Stuart outpost of Heidelberg, where he published a blistering attack on papal policies. He was very fond of bickering. As he was also gluttonous, egotistical, domineering, and avaricious, he immediately offended Abbot, with whom he boarded while preparing Sarpi for the press. The maverick soon discovered that his flight was an error: the food, the wine, the king, and the people were all as bad as the weather. When his old schoolmate Gregory XV, who succeeded Paul V in February 1621, and the King of Spain offered him safe passage back to Rome and reinstatement to his offices, he accepted.36 He had learned nothing from his involvement with Sarpi’s book. Micanzio warned him that other strayed sheep who returned to Rome had bleated their last there. But De Dominis had persuaded himself that his self-imposed mission would excuse him from the “noose, fire, or poison” that Micanzio foresaw.37

This mission was to realize James’s program of uniting Catholics and Protestants around the core Christian beliefs of the apostolic era. In his huge masterpiece, De republica ecclesiastica (1617–22), De Dominis identified aspects of religious worship that he regarded as unnecessary to true belief. Among these “adiaphora” were the cult of saints, play with the rosary, recognition of the supremacy of the pontiff, and the doctrine of predestination. De Dominis’s Venetian friends regarded his project of bringing Rome and Geneva under so wide a tent as crackpot. It was to overlook that the popes of Rome used religion as “a secret of state, and dominion” (Micanzio), that the political power of all religions rested on enforcing adiaphora (Sarpi), and that a united Christendom including the pope was a formal contradiction (Wotton).38 De republica christiana did excite an ecumenical spirit. The Congregation of the Index and the universities of Paris and Cologne joined in banning it immediately.39

De Dominis returned to Rome carrying an English version of the Oath of Allegiance for the pope’s consideration. Gregory preferred to debrief him about English affairs and Sarpi’s dealings with heretics.40 As anticipated, he played the stoolpigeon (“O what a perfidious fellow! what a rascall!”), and, having spouted all he wished, refused to dribble more. That was a mistake. Gregory’s successor, Urban VIII, who had a keen sense of betrayal and a strong allergy to it, sent the fat bishop to slim down in prison. He soon had no need to diet. “Certainly [De Dominis] hath published propositions by thousands every one of which is very sufficient to make him loose his life.”41 He died in custody in 1624, of poison some say and of luck according to others, since the Inquisition did not get around to burning him until three months after his death.42 Since by then Catholics and Protestants alike regarded him as persona non grata, the churches he had failed to bring together when alive united in welcoming his death.43

De Dominis’s enduring contribution to English letters, his edition of Sarpi’s Trent, opened the eyes of Catholics who had not perceived that the hidden purposes of the council were “[to] weaken the lawful Rights of Kings and Princes, to pervert the doctrine and Hierarchie of the Church of God, and to lift up the papacy to an unsufferable height of pride.”44 The recurrent theme of the book is revelation: unmasking popes, penetrating mysteries, exposing secrets.45 All Protestants and anti-Roman Catholics could enjoy Sarpi’s lampoons of the learned divines and academics who played the popes’ game by heaping up trifling objections and ridiculous scruples. “A general disputation arose among them, whether it be in man’s power to believe or not believe.” Another session considered the unanswerable question whether children who died without baptism before the age of reason could make good philosophers. And so on. Sarpi reserved his greatest censure, however, for the cruelty, stinginess (or profligacy), self-interest, and cunning of the various popes under whom the council stagnated.46

A copy of Sarpi’s Trent had a place in the library of gentlemen and theologians. The famous bishops Lancelot Andrewes and James Ussher, both of whom will appear often in these pages, each had a copy, as did Sir John Bankes. It was reprinted fifty-eight times between 1619 and 1710.47 The wealthy Buckinghamshire bibliophile Sir William Drake, whose reading habits were representative of his class, took extracts from it. Popular guidebooks relied on it. Peter Heylin’s Mikrokosmos can stand for them all: “[The Council of Trent] hath caused the greatest deformation that ever was since Christianity began.” The popes who orchestrated it were responsible for the disaster, “so [sayeth] the words of the History.”48 A modern authority on Venice holds that Sarpi’s book was artistic as well as toxic, “[with] some claim to be considered the last major literary achievement of the Italian Renaissance.”49

The year after James’s death an English translation of another of Sarpi’s eviscerating works appeared as The History of the Quarrels of Pope Paul V with the State of Venice. The translator, the Provost of Queen’s College, Oxford, Christopher Potter, advertised it as a work by the man who had revealed to the world “that piece of the Mystery of Iniquity, those Arcana Imperii Pontificii”—that is, the machinations of the Council of Trent. In the new book, anti-Roman Anglophones could read of the heroic stand of the late King James, who had recognized his divine duty to defend Venice and “the Liberty given by God to all Princes.”50

The Mathematician

On 11 April 1609, the British royal family, the Venetian ambassador, and other guests of James’s principal secretary of state, the Earl of Salisbury, gathered at a play celebrating the opening of an emporium Salisbury had built to rival the Venetian Rialto. The goods on display, which the guests took home after the performance, included several optical devices: a prism for studying the rainbow, a convex glass that “makes your lady look like the queen of the fairies and your knight like the grand duke of pygmies,” a concave glass that reverses the effect, spectacles, and the jewel of the collection, a “perspective.” “I will read you with this glass [says the emporium’s proprietor] the distinction of any man’s clothes, ten, nay twenty mile off…the form of his beard, the lines of his face…the moving of his lips, what he speaks and in what language.” This device was not a “parabolical fiction,” like the burning mirror that from the top of St Paul’s could set a ship on fire twenty leagues at sea, but a realized object, “a perspective glass” for which the bill of purchase still exists.51

Salisbury’s perspective was a low-power spyglass of the type then recently invented in Holland. Among the first to have one was Archduke Albert VII of Austria, Governor General of the Spanish Netherlands. It amused the court to deploy it during excursions in the countryside (Figure 9). Around April Fools’ Day in 1609 the archduke showed it to the papal nuncio, Galileo’s former student Guido Bentivoglio, a man of great capacity, learned, ascetic, acute, jolly, and a frequent actor in these pages (Figure 10). Bentivoglio glimpsed the potential of the instrument; he had studied with Galileo in Padua and knew something about optics. He hurriedly acquired a spyglass and sent it to Rome, where it made its way to the Jesuits at their intellectual headquarters, the Collegio Romano. They turned it to the heavens before Galileo had one in his hands, but they did not see anything through it undreamt of in their philosophy.52 The low-power Dutch spyglass was a toy, the sort of thing that occupied the company of Foolosophers created in 1609 by the satirical Calvinist Joseph Hall, later Bishop of Norwich. Hall arranged his Foolosphers in two colleges, one given to making such novelties as spyglasses, the other to debunking them. The debunkers doubted their senses. “Strike one of them as hard as you can, he doubts of it, both whether you struck him hard or no, & whether he feele it or no.”53 These heroes of Foolosophy would soon have real-life colleagues who denied the reality of the celestial novelties perceived through Galileo’s telescope.

Figure 9 Jan Breughel the Elder, Extensive Landscape with View of the Castle of Mariemont (c.1610), detail. Archduke Albert and Nuncio Bentivoglio would have employed their primitive telescope in much the same way on their contemporaneous excursion.

Figure 10 Antony Van Dyck, Cardinal Guido Bentivoglio (c.1623); the cardinal was Van Dyck’s first major patron in Italy.

A few months after the spyglass had made its debut in Salisbury’s emporium and the Collegio Romano, a peddler offered one to the Venetian Senate. The senators consulted Sarpi. He examined it, deduced its operation, and advised against buying it. He knew how to make a better one: ask the mathematician at the university. Always needing money, Galileo ran a workshop that made spectacles, calculating instruments, and other small things to supplement his professorial income. Sarpi described the spyglass. Galileo perceived its military and commercial value and grasped the opportunity to add it to his inventory.

Late in 1609, Galileo turned his telescope, now capable of magnifications up to thirty times, to the heavens, and opened a new world. The mysterious Milky Way turned out to be a vast collection of dim stars. The moon, violating standard physics, was not a smooth globe of extraterrestrial quintessence, but a rocky ball much like the earth. And, most extraordinary of all, some small bright dots, never seen before, moved along with Jupiter, sometimes preceding and sometimes following him. Galileo identified the dots as four satellites circling the planet. Our earth was not unique in possessing a moon! Moreover, since Jupiter’s satellites stayed with him in his travels, Copernicans did not have to worry that a moving earth might lose its companion. With an eye to his future as well as to the heavens, Galileo hurriedly published his Sidereus nuncius with a dedication to his former pupil, Cosimo II, Grand Duke of Tuscany, and personalized the gift by naming the four satellites of Jupiter the “Medici stars.” He did not bother to explain how the instrument worked, an omission that Archbishop De Dominis tried to supply.54

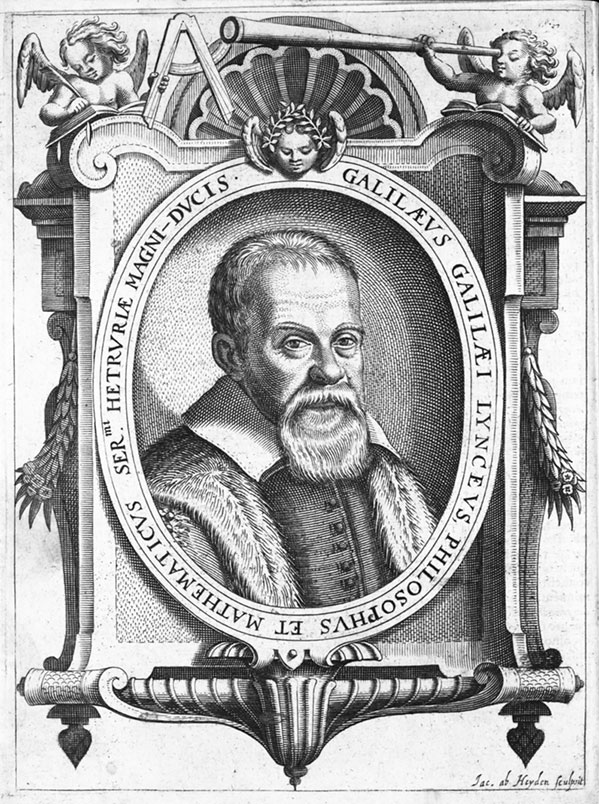

Although Galileo did not stress the point, his discoveries, by making the moon earthlike and the earth planet-like, supported the Copernican system. But neither did he pretend, as Copernicus had, that his discoveries had ancient antecedents; he did not mention that Plutarch and many others, including his favorite poet Ariosto, had interpreted the moon’s visible features as hills and seas. Perhaps he claimed too much. But he had found great novelties in the heavens and, what was more, he took responsibility for them. In this he differed capitally from Sarpi and De Dominis. They agitated for a return to a state of Christianity that they supposed had existed before the innovations of power-grasping popes; he, for a new, revolutionary, unprecedented view of the world (Figure 11).

Figure 11 The Grand Duke’s philosopher and mathematician: Galileo (c.1613), by Francesco Villamena, as reproduced in Galileo, Systema cosmicum (1635, 1641).

The news from the stars ran quickly to England. On the day of its publication, Wotton sent a copy of Sidereus nuncius to Salisbury for delivery to their sovereign with the following advertisement:

[It is] the strangest piece of news…that he hath ever yet received from any part of the world…four new planets rolling about the sphere of Jupiter, besides many other unknown fixed stars; likewise the true cause of the Via Lactea, so long searched; and lastly, that the moon is not spherical, but endued with many prominences, and, which is of all the strangest, illuminated with the solar light by reflection from the body of the earth…So as upon the whole subject he has first overthrown all former astronomy…and next all astrology…[T]he author runneth a fortune to be either exceeding famous or exceeding ridiculous.”55

Soon the English market was flooded with poor-quality perspectives. An Italian who proposed to sell lenses in London received the answer that “perspective glasses are here common.” But not good ones; glass perfect enough for telescopes was rare.56 Consequently, Galileo’s discoveries at first did not spread by observational test, as he recommended, but by the written word, although Sidereus nuncius itself quickly became rare. After Galileo had lobbied successfully for the resounding position of Mathematician and Philosopher to the Grand Duke of Tuscany, the Florentine diplomatic service distributed copies of the book. Its ambassador in London, Ottaviano Lotti, offered one to King James, who thus had the new world in duplicate.57

Galileo’s disclosures caused the stir that might be expected from the first revision of the world since that evening in October, 4004 bc, when, according to Archbishop Ussher’s careful calculations, God “ushered in” (so he put it) the universe. Some early readers extolled Galileo as the new Columbus; others denounced him as a charlatan; and many sat on the fence. Conspicuous among the denouncers was Martin Horky, a true Foolosopher, who objected that the telescope created the sights seen through it and that, even if the Medici stars existed, they would be useless, since judicial astrology did well without them. Horky’s objections briefly occupied the attention of several of King James’s subjects then in or around Padua. One of them hesitated whether to believe in the rocky moon or “the 4 new Medicea [S]idera, found out by Galileo,” but accepted the resolution of the Milky Way into stars and the ability of Copernican astronomy to predict phenomena “as truely, as we that [think] the Heavens [in] motion and the Earth to stand still.”58 A Catholic Scot studying at Padua, John Wedderburn, a protégé of Wotton, undertook to rebut Horky. What was the use of the Medici stars? Wedderburn: To vex people like you, Horky, “who superstitiously try to apply the least glimmers in the heavens to particular effects and want to govern the free will of men.” What was the use of Galileo’s discoveries? “To liberate posterity from astrology.”59 Were all Galileo’s observations persuasive? The disciple hesitated. Although he allowed that the telescope reliably enlarged distant objects and revealed ones undetectable without it, Wedderburn could not understand how it could show an object differently shaped from its appearance to the naked eye. He therefore doubted Galileo’s detection of the phases of Venus, although many astronomers accepted them as proof that the planet’s orbit encircled the sun.60

The Jesuit mathematicians of the Roman College entertained Galileo in 1611. A Catholic Englishman, George Fortescue, who then boarded at the English College, was present. Perhaps paraphrasing conversations he heard there, Fortescue wrote a dialogue in Latin between Galileo and two of the mathematicians, the patriarchal Christoph Clavius and his more liberal disciple Christoph Grienberger. Fortescue begins his dialogue with Clavius’s account of powerful lenses and a tall story about an engraver who stared so hard at his work that his spectacles were riddled with holes; then deviates to astrology; and returns to optics with the telescope and the discoveries made with its aid.61

The Jesuits accepted the discoveries, both in Fortescue’s report and in fact, as did other important Roman churchmen and laymen to whom Galileo demonstrated them. Among the impressed laity was the young nobleman Federico Cesi, the founder of the Accademia dei Lincei (“Of the Lynxes”), a small keen-eyed group interested in natural science. Galileo joined it and advertised himself as a lynx in several of his publications, including the Dialogue. By the time Fortescue wrote up his Feriae academicae (“Academic holidays”) in the late 1620s, Cesi’s lynxes included Cardinal Francesco Barberini, the powerful nephew of Pope Urban VIII. Probably the “Roman academics” to whom Fortescue dedicated his book, and among whom he specially mentioned Barberini, were the lynxes. When Galileo received Fortescue’s short dialogue, his great one was nearing completion.62 He had worked on it for twenty years, he informed Fortescue, and still it lacked important information. Do you know any unusual certain facts about the tides? “In the book I enquire into their most hidden causes, which have stirred up more commotion among philosophers than in the sea itself, and which, unless I deceive myself, I explain marvelously.”63 He deceived himself grievously.

In Fortescue’s dialogue, Grienberger anticipates Galileo’s subsequent career with the warning, “if you are thinking about Copernicus, go cautiously and timidly.” And he points the admonition by asking what Galileo had to say about the inhabitants of other worlds.64 Galileo’s friendly rival Johannes Kepler replied to a similar question by writing a book about life on the moon. Galileo dissociated himself from such speculations for fear of association with Bruno and also, perhaps, because he did not believe in extraterrestrial intelligence. But it was so obvious an inference! Ben Jonson easily inserted it into a play in 1611: Love, helping Cupid to unravel a riddle that required finding “a world without,” observes that “[it] is already done, And is the new world i’ the moon.”65 Galileo did not heed the advice Grienberger gave him in Fortescue’s fiction and probably also in real life.

The most important immediate response to Sidereus nuncius by an Englishman came from an old friend of Wotton. He was the poet John Donne, writing in prose and exploiting Galileo’s lunar observations in a lengthy satire, Ignatius his Conclave (1611), aimed at the Society of Jesus. Frequently reprinted, Ignatius helped to keep Galileo in the English mind and, by joshing with the implications of innovation, to enrich the significance of the emblem in Cleyn’s picture. In Donne’s satire, the Jesuits make innovation, especially of items that “gave affront to all antiquitie, and induced doubts, and anxieties, and scruples, and…a libertie of believing what [one] would,” the main qualification for entry into Hell. Copernicus, deeming himself so qualified, demanded accommodation. Acting as Lucifer’s lieutenant, Ignatius inquired what novelty Copernicus had produced to assist the Devil. Merely exchanging the sun and the earth did not suffice. “What cares [the Devil] whether the earth traveil, or stand still?” Perhaps Copernicus upset a few philosophers. But that achievement scarcely counted compared with the supererogatory work of confusion engineered by the Jesuits’ great mathematician Clavius—that is, the Gregorian calendar, which put ten days between Europe and England. Still, Ignatius granted, Copernicus was a controversial innovator and might qualify for admission to Hell if the pope declared, “as a matter of faith, That the earth does not move.” That would raise hell. Until then, Copernicus lacked the necessary qualifications.66

Next come the radical physician Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus [Paracelsus] von Hohenheim, whose name sounds like an exorcism, and the more congenial Machiavelli. Ignatius defeats both; the Jesuits and the popes know as much about poisoning as Paracelsus and far outdo Machiavelli in lying. Columbus fails also, on the ground that all the mischief resulting from his discoveries was the work of the Jesuits.67 Ignatius’s high barrier makes Lucifer worry that only Jesuits will be allowed into Hell. How rid himself of them? Call in Galileo! What? Yes, Galileo, whose glasses when blessed by the pope will have the power to draw the moon as close to the earth as desired. “And thither (because they ever claime that the imployments of discovery belong to them) shall all the Jesuits be transferred.” Ignatius agrees, having heard from Clavius that the lunatic queen is easy to lead and because he expected to use the moon as a launchpad for conquering the stars. But before Ignatius can set out, news of his canonization reaches Hell. The pope had yielded to the Jesuitical argument that, since animal butchers have their saint, spiritual butchers should have one too. Saints undoubtedly have a right of residence in Hell. Ignatius remained there.68

Since the first version of Ignatius, in Latin, entered the Stationers’ Register on 24 January 1611, Donne must have begun it within a few months of the publication of Sidereus nuncius. A year later, after he had pondered the ramifications of Copernican ideas more closely, he decided that the innovation did indeed shake the foundations of established learning, and published the famous lines:

And new philosophy calls all in doubt

The element of fire is quite put out

The sun is lost, and th’earth, and no man’s wit

can well direct him where to look for it

. . . . .

’Tis all in peeces, all cohaerance gone

All just supply, and all relation.69

With this change of tone, Donne sounded as alarmist as the cardinals of the Inquisition.

While Galileo tried to restore coherence by advocating Copernican astronomy more openly and aggressively, the Inquisition was looking into its compatibility with Scripture. We know the result of its interdisciplinary deliberations. The head of the Inquisition’s Copernican committee was an Irishman, Peter Lombard, then laboring to complete a gigantic manuscript responding to King James’s criticism of his activities as head (in absentia) of the Catholic Church in Ireland.70 Perhaps the Irish Question prevented the learned Lombard from giving his full attention to the Copernican one. On the strength of his committee’s brief report, the Inquisition condemned heliocentrism and the Congregation of the Index banned Copernicus’s mathematical masterpiece “until corrected.”

Galileo had come to Rome in 1616 on his own initiative before the rulings of the Inquisition and the Index in the hope that he could persuade their cardinals not to act foolishly. Many prelates already knew his views on the interpretation of Scripture, which were circulating in an unpublished letter he had written to Cosimo II’s mother, the Grand Duchess Christina. Although the Council of Trent had prohibited amateur theologizing, the Roman establishment did not rebuke Galileo publicly for his theology or cosmology. Instead, the pope, still Paul V, deputed battle-hardened Bellarmine to tell Galileo privately about the Inquisition’s decision. Under circumstances not entirely clear, at the same session Galileo received the additional order not to hold or teach the Copernican theory in any way at all. Bellarmine acknowledged, however, that, if irrefutable proof of the earth’s motion and the sun’s immobility were found, the Church would have to rethink its position. This was more a statement of logic than of policy, however, since he deemed such a proof to be infinitely unlikely.

Galileo thought he might have found one in his unfortunate theory of ocean tides. In his solution, probably invented in the 1590s by Sarpi, a combination of the earth’s spin on its axis and revolution around the sun agitates the waters: and, more aggressively, only if the earth so moved could there be tides at all. Galileo wrote out this theory for the first time in January 1616 as a letter to a young cardinal who was to deliver it in time to influence the deliberations of Peter Lombard’s committee. Although it probably did not reach its destination, like the letter to the Grand Duchess it circulated widely in manuscript. It raised universal interest and puzzlement, since the theory had no place for the moon in generating diurnal tides. That disagreed with the experience of all mariners and also of Shakespeare’s witch, the mother of Caliban, “one so strong ǀ That could control the moon, make flows and ebbs [of the sea].”71

England’s Sarpi

Like Sarpi, Francis Bacon, Attorney General and Lord Chancellor, revolved in the highest circles of government. They also shared political views and interests in natural knowledge and enjoyed reputations for superior wisdom and learning. Through Micanzio and the apostate Tobie Matthew, a relative of Bacon, they knew about one another’s thinking, which, in respect of Galileo’s claims, differed fundamentally.72 Sarpi approached physics as a mathematician and accepted Galileo’s astronomical observations and deductions; they were obvious enough, he held, and urged Galileo to return to the important traditional philosophical problems of motion, gravity, and levity, which the Copernican system had made more difficult and pressing.73 Bacon approached knowledge claims as a lawyer and welcomed Galileo’s discoveries as so many proofs of the poverty of the physics taught in the schools. He also regarded the problem of gravity, of “the heavy and the light,” as important, and wrote a little tract about them that would excite the interest of Maurice Williams. But, whereas Sarpi expected that Galileo would find a science of motion capable of handling the Copernican system, Bacon was almost as certain as Bellarmine that he would not.

Bacon’s method recommended caution. Does the universe have more than one center? “Those little wandering stars discovered around Jupiter by Galileo” would confirm the concept, “if the report can be trusted.” The old problem of the nature of the Milky Way seemed to be nearing resolution, “if we are to believe what Galileo has reported.” We are not far from Foolania: Galileo’s ongoing observations have raised “some suspicion” that the sun’s face has spots.74 Bacon soon discovered that, although Galileo’s observations passed muster, his way of reasoning did not. The proof was in the tides. In an unpublished tract of 1611, Bacon supposed that the seas circulate from east to west in sympathy with the diurnal motion of the heavens; that the moon’s position modulates the circulation and the continents obstruct it; and that the combination produces two high and two low tides a day synchronized to the moon’s passage. In contrast, Galileo derived the ebb and flow from the rotation of the earth, “a supposition arbitrary enough, as far as physical reasons are concerned.” Indeed, altogether false.75

While Galileo was chuckling over Bacon’s tidal theory, his own came under fire from another Englishman, Richard White, a student of mathematics at Pisa. Clever enough to argue with Galileo, or, as Matthew judged, “too soft” to know his limitations, White observed, correctly, that Galileo’s theory could not easily deliver more than one high and one low tide a day. Galileo seems to have hesitated over this criticism, but only briefly; and when White returned to England via Matthew in Belgium, he had with him several of Galileo’s published books, including Sidereus nuncius, and a few of his unpublished manuscripts, including “On the Tides.” Matthew sent this last item to Bacon.76 The chancellor was then putting the final touches on his Novum organum (1620), which ruled out Galileo’s tides on two counts: in theory, because “devised upon an assumption which cannot be allowed, viz., that the earth moves;” and by observation, by “the sex-horary motion of the tide.”77

When Wotton returned to Venice for his third stint as ambassador in 1621, he had several copies of his kinsman Bacon’s Novum organum in his baggage. He thought that this famous diagnosis of the ills of received learning would be very nourishing for his Venetian friends. “[I]t is not a banquet that men may superficially taste…but in truth, a solid feast, which requireth due mastication.” Micanzio had the teeth for Bacon.

[I]f he brings his worke to the perfection he promiseth [thus Micanzio], Philosophy would be more beholding to him than it was ever yett to any, nor can I compare him to any…For the philosophy of theis tymes is but a Logick full of words, but that singular witt, truly singular, peirceth into the rootes of the defects thereof.

Another cracker of tough nuts, Kepler, received a copy of Novum organum from Wotton’s own hands. Knowing Kepler’s difficulties as a Protestant in a Catholic country and as an Imperial Mathematician living more on his title than his salary, Wotton invited him to England. Alas, Kepler was as irrationally attached to the Empire as Sarpi was to Venice.78

Like Galileo, Bacon advertised the innovative character of his “new instrument” for exploring the world. Unhappily, he had no practicable plan of execution. Where would he have found staff? Galileo had not met his standard, nor could other mathematicians, owing to their “daintiness and pride,” their reliance on fictions, and their tendency to domineer over other cultivators of science.79 Oxbridge dons could not fill the bill either, for reasons given in Novum organum. Even so devoted a follower as Micanzio recognized that Novum organum was a collection of axioms, “food so substantiall that it must be taken by littles, and converted by study into nature,” and not a blueprint for collective action.80 Not until the end of his life did Bacon indicate, and only in the form of a utopia, how his vision might be achieved.

Bacon compiled human as well as natural histories, from which, and his own rich experience, he extracted such wisdom as is found in his popular Essays on moral matters. Both Matthew and Micanzio tried to exploit the Essays for cultural warfare in Italy. Matthew hoped that an edition addressed to the Grand Duke of Tuscany might persuade him that not all English Protestants were savages and that closer ties with Bacon’s master, King James, were practicable. An Italian translation of the Essays was at hand. The translator, William Cavendish, soon to be the second Earl of Devonshire, had learned his Italian in Venice with the help of Micanzio; his errors in rendering Bacon were corrected by De Dominis; whence arose a reliable text that would have suited Matthew’s purpose perfectly had it not contained two obnoxious articles. One ridiculed disputes over indifferent religious beliefs and another charged the Catholic Church with “sensual rites and ceremonies, excess of outward and pharasiatical holiness, [and] over-great reverence for tradition.”81 At Matthew’s request Bacon agreed to remove the offensive essays and the Italian text intended for Florence came forth from London in 1618 without them. It also lacked the preface Matthew had added describing his author’s high status in England.82 Mention of Bacon’s name and distinctions would have triggered the general ban against books by heretics. Micanzio had the book reprinted in freer Venice with the author’s name, “Francesco Bacchon,” but otherwise left it alone. Even in the Serenissima it would have been dangerous to include the anti-Roman essays of a heretic.83

Italian Attractions

Many Englishmen had hands-on experience of the art, architecture, and courtesans of Venice. Guidebooks warned against visiting these last attractions while allowing that discussing religion might be riskier. Another great draw was the ghetto. Most Englishmen had never knowingly set eyes on a Jew at home since few lived there openly between their expulsion in 1290 and their readmission in 1655. The well-traveled Thomas Coryate, who published his observations as Crudities, attempted the double feat of converting a courtesan to chastity and a rabbi to Christianity. His attempt on the rabbi almost ended his crudities. Ben Jonson described the adventures.

A punk here pelts him with eggs. How so?

For he did but kiss her, and so let her go

. . . . .

And there, while he gives the zealous bravado

A rabbin confutes him with the bastinado.

Luckily Wotton was gliding by in a gondola when the rabbi’s entourage turned belligerent. Rescuing Englishmen who trespassed on native sensibilities was a frequent service of the “thrice worthy [English] Ambassador.”84 The worthy ambassador had several Jewish friends, including his landlord and Leone Modena, the author of a famous account of Jewish practices composed for gentiles, perhaps with Wotton’s coaxing. Since Modena was one of the few rabbis in Venice who spoke Latin, he might have been the rabbi in Coryates’s tale. If so, Wotton’s timely appearance might not have been a miracle.85

More dangerous than flirting with bawds or arguing with rabbis was talking with Jesuits. According to Joseph Hall, the man of Foolosophy, these sneaks knew the names of all notable English travelers, lay in wait for them, and (as we know from Tobie Matthew) turned their heads with gorgeous churches, exquisite music, and discourses they could not answer.86 The danger for heretics grew in proportion to distance south of Venice. Reliable advice to non-Catholic Englishmen planning a visit to Rome recommended learning another language well enough to pass as a native; in this way the famous traveler Fynes Moryson, presenting himself as a Frenchman, succeeded in gaining an interview with the future Urban VIII. In the Papal States or Naples, the wise Englishman avoided conversations with fellow countrymen, never talked with Italians about religion, and abstained from urging anyone to convert. As further precautions, he changed his residence and restaurant frequently, and never fell sick.87

Wotton owed his ambassadorship to his mastery of masquerade. He became so thoroughly an Italian during his early travels that in 1601 he made it all the way from Florence, where he had earned the confidence of the Grand Duke, to Scotland, where, using the name Ottaviano Baldi, he obtained an interview with King James. He had come to warn James (so he said in Italian) against a papal plot to poison him, and to bring him, as a present from the Grand Duke, a box of infallible antidotes. Baldi then disclosed that, although the threat was real, he was a fake, not an Italian but an Englishman needing asylum. He had pretended to be a Florentine to bamboozle Queen Elizabeth’s spies: as the one-time foreign secretary to the treasonous Earl of Essex, he feared imprisonment if recognized.88 When James became King of England in 1603, he summoned Ottavio Baldi, knighted him, and sent him back to Italy as the first English ambassador to Venice since the accession of Elizabeth.89

Wotton had adopted a more extravagant masquerade to visit Rome. Disguised as a German Catholic (he had learned the language perfectly), he drank like a Teuton, dressed like a buffoon, and in the guise of a conspicuous idiot came to know more about the operations of the Roman establishment and the papal court than (he boasted) any other non-Catholic Englishman. He stalked the pope. “The whore of Babylon I have seen mounted on her chair, going on the ground, reading, speaking, attired and disrobed.”90 He prudently gave up this counterfeit on being recognized and returned home to begin his unfortunate engagement by Essex.

The master unmasker, Fra Paolo, was also the strongest advocate of dissimulation. He called it “moral medicine.” Just as a doctor sometimes deceives his patients to promote health or ease death, so may the politician and the priest tell lies to secure the state. Feign agreement, Sarpi says, guard your thoughts, volunteer nothing. “I have to wear a mask because without one no man can live in Italy.”91 The sure way to traverse the world safely, according to an experienced Roman courtier of Wotton’s acquaintance, is to keep “your thoughts close and your countenance loose [sciolto]”—that is, blank and open.92 “[B]eware ǀ You never speak a truth,” echoes Jonson’s Sir Politic Would-Be, summing up his Venetian lessons, “And then, for your religion, profess none ǀ But wonder at the diversity of all.” The English Sarpi advised similar behavior: “nakedness is uncomely, as well in mind as in body; and it addeth no small reverence, to men’s manners and actions, if they be not altogether open …Therefore set it down, that an habit of secrecy, is both politic and moral.”93 Copernican astronomers followed the advice: Kepler urged its use in the great cause, and Galileo’s spokesman in the Dialogue states more than once that he wears a mask.94

Beguiling, inspiring, seductive, frightening, repellent—thus was Italy in the eyes of the Stuart traveler. The land of Titian, Galileo, and Sarpi, but also the headquarters of Jesuits, popes, and the Inquisition; home to the world’s most accomplished artists and assassins, rational philosophers and duplicitous theologians, nuns and courtesans. The longer the unprotected Protestant tarried among the allurements and dangers, the more likely and fearful his fall. That is what Sir Thomas Parker warned in his Essay on Travailes of 1606. Beware of Italy! Beware the “infinite corruptions, almost inevitable, that invest travailers after small abode there.”95 Would you let your son go to Italy? Travel can be broadening, answers Wotton. “But these effects are not general, many receiving more good in their Bodies by the tossing of the Ship, whilst they are at Sea, than benefit in their Minds by breathing a foreign Air, when they come to Land.”96 Quite right, says Sir Politic, scoffing at “That idle, antique, stale, grey-headed project ǀ of knowing men’s minds and manners.”97 Yet it is also true, answers Coryat, that knowing the bad can do a virtuous man good. “[He] will be more confirmed and settled in virtue by observation of some vices.”98

Wotton did what he could to direct observation in the right direction. He ran something of a “college” (as Coryat called it) of art and architecture in which Englishmen could learn to appreciate things they could not see at home.99 Few of them came with any knowledge of fine art, indeed, saw little difference between good painting, house decoration, and face painting. Bankes’s patron, Lord William Howard, a man of wide experience and antiquarian tastes, engaged the same man to mend his cabinets, paint his house, and portray his family.100 The portraits travelers may have seen at home tended to be flat and decorative, as in the gorgeous presentations of Elizabeth; or to be rough and approximate, as in the depictions of relatives; or missing, as in foregone representations of the Savior, Apostles, and Martyrs.101 People who did appreciate fine painting knew it primarily from the work of north European masters. After 1600, modern Italian art slowly made headway among English connoisseurs; but as late as the 1620s, according to one of Francis Cleyn’s painter friends, Edward Norgate, “chiaroscuro” was just plain obscure to most of James’s subjects. Henry Peacham, the designer of perfect courtiers, hesitated before recommending knowledge of painting of any kind in The Compleat Gentleman (1622). And, when Robert Burton finally included painting among remedies to melancholy in the fourth edition of his Anatomy (1632), he omitted modern Italian art from his therapeutic examples.102

Wotton played a major role in bringing his countrymen to appreciate Venetian art. Acting as consultant to travelers and purchasers at home, he helped English connoisseurs to value the older Italian masters, above all, Titian, and, among the newer, the Carracci, Caravaggio, and Guido Reni. Occasionally he gave a valuable work to a patron able to appreciate it; less sensitive souls got cheese.103 The greatest of the connoisseurs whose appetite he sharpened was the haughty Catholic Earl of Arundel, whom the Venetians knew as the extravagantly rich premier noble of England and treated accordingly.104 In time Arundel’s passion for collecting art and artists exceeded even his pride in the exploits of his family. A year after regaining England in 1614 with trunksful of art objects and a gondola, he began to accumulate a virtual academy of artists and intellectuals with virtual headquarters in his Italianate London establishment, Arundel House. Among its members were the authority on gentlemanly manners Peacham and the artist Norgate, who taught Arundel’s children to draw and gathered paintings for him in Italy.105 Among other frequent visitors to Arundel House was the earl’s uncle, Lord William Howard.

Arundel’s Italian pictures inspired emulation in the shallow mind of King James’s favorite, Robert Carr, Earl of Somerset. He and Arundel made use of Wotton, Carleton, and the same Daniel Nijs who acted as intermediary between Wotton and Sarpi to procure paintings. When Carr fell from grace, Arundel had the pick of his collection and so, until King Charles entered the competition, built up the finest collection of Italian art in England.106 He also promoted the visits of important north European artists, including Mytens, Van Dyck, and Cleyn. Portraiture was another route by which Venetian painting came to the attention of Englishmen. Carleton, Wotton, Arundel, Lady Arundel, and others who could afford it sat for Domenico Robusti (Tintoretto junior), who painted their portraits about the same time he did Galileo’s.107

With Wotton’s advice, English travelers explored the modern churches, palaces, and villas in which the recent artistic productions of Italy were open to view. Wotton had made a particular study of the writings of Palladio, Serlio, and Scamozzi and their buildings in the Veneto, and collected their architectural drawings. At the end of his third stay as ambassador, he deposited his knowledge of the art in his Elements of Architecture (1624), a piece of pedagogy designed to help him to win appointment as Provost of Eton College. The book impressed the then-current favorite, the Duke of Buckingham, the King, and the Archbishop of Canterbury, and helped Wotton win the post over the formidable competition of Bacon and Carleton.108

Wotton’s Elements, though an epitome of Venetian practice, is regarded as the first original English work on architectural theory.109 It employs technical terms previously wanting in English, which Wotton introduced together with the observation that their lack indicated the relative inferiority of English architects.110 Neither the argument nor the evaluation applied to Inigo Jones, who had lived in Venice and had access to Wotton’s collection of architectural drawings. Jones was to incorporate Venetian concepts in English buildings following a steady royal ascent: he began as “picture-maker” to Christian IV of Denmark, who passed him on as a designer of stage sets to his sister Queen Anna of England, who passed him on as a surveyor of palaces to her son Henry Prince of Wales.111 After Henry’s death in 1612, Jones returned to Italy with the Arundels. During their stay in 1613–14 he sketched villas, temples, and palaces, both ancient and Palladian, and allowed himself to be sketched by one of Galileo’s portraitists, Francesco Villamena.112

Jones’s importation of Italian styles included stage sets. The first among many extended notes that he made on his copy of Palladio’s Quatri libri dell’architectura (1601) described the theater at Vicenza where Palladio painted scenes in perspective to give the illusion of depth to the stage. That was a great accomplishment, although Palladio’s scene did not change: “the cheaf artifice was that where so ever you satt you saw on[e] of these Prospectives.” Deception everywhere! Serlio’s Five Books of Architecture (1611) treats perspective in detail before applying it to stage design. He advised that tragedies be set in grand houses in which the noble people destined for trouble can suffer comfortably and that comedies take place on a street with ordinary houses, “but especially there must not want a brawthell or bawdy house, and a great Inne, and a Church; such things are of necessities therein.”113 Jonson often followed this advice.

To effect the quick changes that made the spectacle, Jones improved on machinery he had seen in Florence and Venice. A rotatable stage with different back-to-back scenes, pairs of parallel sliding shutters with different perspective views, openings under the main stage for underground activities, rising and descending platforms for heavenly ones, created a three-dimensional hieroglyph, to use the term of the author of Queen Anna’s first masque in England, Samuel Daniel.114 The most evident hieroglyphs bound the heavens, in which the stage machinery placed the gods and personifications who appeared in the masques, to the earth of everyday experience. Messages ran from the gods to the earthlings below as so many siderei nuncii; “the entire celestial world that is said to govern the universe [is revealed] as if through a magical and powerful telescope…[showing] what is happening in the moon…[and] the stars dancing.”115 Masque-goers frequently encountered astronomical hieroglyphs in Jones’s engineering and his collaborator Ben Jonson’s plays. And theatrical hieroglyphs reciprocally occurred in the frontispieces to astronomical books, notably Galileo’s Dialogue.116

From all of which follows that no one had to face the dangers of travel to know the binary calculus of Italy. The English stage, anti-papal propaganda, the doings of Sarpi, De Dominis, and Galileo, the lure and lore of Venice, travel books, competition for artworks, Jones’s buildings, and so on, kept the puzzle of Italy alive among stay-at-home gentlemen like Sir John Bankes through the reigns of the first Stuarts.