Carceral Shadows

Entangled Lineages and Technologies of Migrant Detention

DAVID MANUEL HERNÁNDEZ

Other Incarcerations

This chapter examines the connective tissues and tense relations shared by U.S. prison and detention apparatuses through the exploration of roots, foundations, and trajectories of immigrant detention in the context of the U.S. prison. It considers what Gerald Neuman terms the “lost century of immigration control” that occurred alongside slavery and emancipation prior to the consolidation of the federal immigration authority.1 These roots of detention reflect a complex history of immobilizing, isolating, and forcefully removing black, Indigenous, and, later, migrant bodies within and from the nation. The chapter is a story not of progress or decline but of the entrenchment of legal and material powers over noncitizens. It discusses the maturation of technologies of detention and removal that followed the institutionalization of federal immigration control bureaucracies and practices in the 1890s. The malleable transposition of racialized targets of immigration enforcement is a critical technology in the history of immigrant detention. These racial dimensions are explored through an analysis of the foundational enforcement focus on Asian migration through a transition to a robust and iconic criminalization of Latina and Latino “illegals” in the latter half of the twentieth century. Although Asian and Latino detainees share the historical stage with other immigrant detainees, white and nonwhite, the targeting of Asian and Latina/o immigrants in immigration enforcement is pervasive, influential, and emblematic. Finally, the chapter discusses the contemporary merger of criminal and immigration law and enforcement that is occurring today. All told, it expands the historical understanding and future political horizons of carceral regimes by considering a multiracial and parallel site of incarceration, expulsion, and punishment.

One might ask where, or perhaps if, a chapter on immigrant detention belongs in a volume centered on carceral studies. After all, immigrants in detention are not serving criminal sentences. Their confinement is not related directly to a criminal conviction. Nor do they labor in prison industries. Immigrant detainees, instead, are incarcerated pursuant to their involuntary removal from the United States. They may be undocumented persons, asylum seekers, temporary visitors in violation of visa regulations, or legal permanent residents who have committed deportable acts.2 For these reasons and others, the study of immigrant detention is often situated marginally alongside the larger discourse on prisons and prison abolition. But there are linkages and correlations, as well as critical disjunctures, between these two carceral states. Immigrant detainees, for example, are easily conflated with the criminally imprisoned through racist stereotypes and the multifaceted force of criminalization technologies. Apprehended at ports of entry and also the interior of the nation, detainees often reside in the same or similar facilities as the criminally convicted, including the majority in nearly 250 local jails and private prisons nationwide, as well as six federal service processing centers. As a result, detainees are often counted among incarcerated persons in the U.S. prison industrial complex—accounting for infrastructural growth and body count—but with less a focus on the regime’s legal and historical particularities. A unique set of guiding policies and legal purviews manages the detention of immigrants, including a different court system and a particular legal jurisdiction—a federal one. Detainees might be a part of the prison system spatially, but they are also generally apart from that system legally.

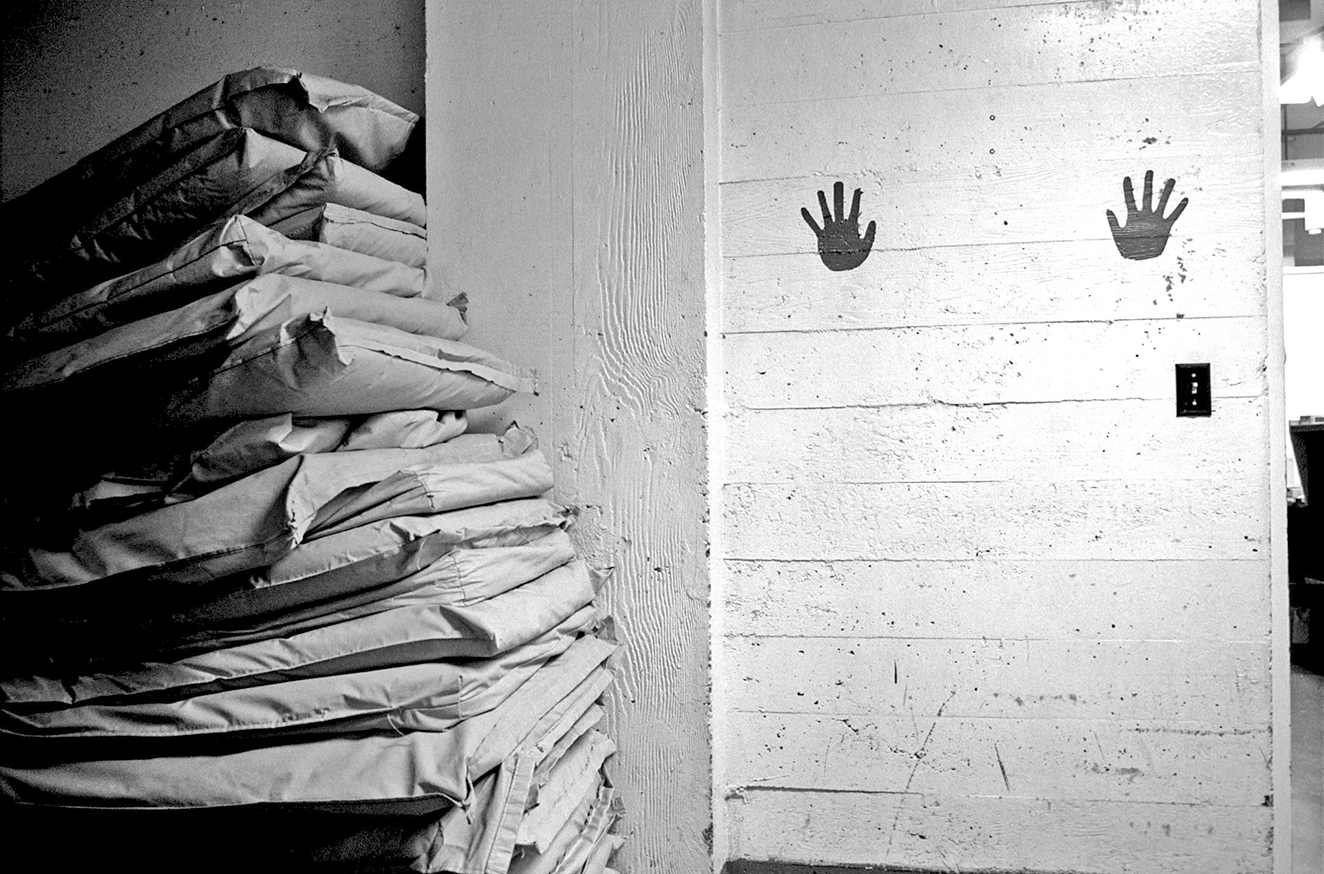

Figure 1 Steven Rubin, Handprints, Federal Detention Facility, Seattle, Washington, 2001. Courtesy of the photographer.

Today, the enormity of the prison industrial complex and its prolific and radical array of scholarship eclipses, it seems, immigrants in detention. For one, the quintupling of immigrant detainees that has occurred in the last twenty years suggests that detention expansion is a late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century quandary, and not one that has lasted for over one hundred years. In what is considered the “fastest-growing form of incarceration,”3 roughly 40,000 immigrants are detained daily (compared with 7,000 in the mid-1990s), and roughly ten times that amount pass through detention annually. Deportations amounted to nearly 400,000 at the end of the Bush administration and peaked in 2013 at 438,000, as President Obama exceeded his predecessor in this task, expanding a variety of enforcement practices nationally.4 Signaling a continued increase, the Trump administration oversaw a 38 percent increase from the previous year in immigrant arrests in its first one hundred days.5 Significant as the numbers are, these figures pale in comparison to 2.3 million persons caged daily in federal, state, and local prisons and jails as a result of criminal arrest and conviction. Further, within policy discussions of comprehensive immigration reform (CIR), detention is far down the list of priorities behind legalization and amnesty, guest worker programs, border militarization, workplace raids, and the plight of undocumented university students. In fact, most recent legislative attempts at CIR by both political parties included expansions in detention enforcement, such as expanding the list of deportable crimes for noncitizens, removing barriers to indefinite detention, and expanding fast-track deportation processes that bypass court backlogs. Certain to expand the system’s infrastructure, most detention reforms under the guise of CIR also include criminalizing “gang affiliation”6 in lieu of criminal acts and criminalizing persons providing life-saving aid to persons entering the country without inspection.7 These trends reflect the merger of criminal law enforcement with immigration bureaucracies.

Detention’s entanglement with the U.S. prison system, as this chapter suggests, requires the recognition of these parallel and often intersecting carceral histories and also a disentangling of the institution to reveal its distinct trajectory. As a carceral institution, detention reflects a variety of technological consolidations and accumulations of legal, administrative, and generally nationalist state power over immigrants, especially nonwhite immigrants. Just as Hogan suggests that the U.S. national security state stemmed from perceived military threats of the Cold War in tension with a political culture that feared a “garrison state,”8 expansions of immigrant detention mirror this pattern: depending on perceived national crises and a merging of racist and xenophobic cultural practices in tension with the nation’s self-perception as a haven for immigrants. The genealogy of detention reveals a long period (from the 1890s to the present) of bureaucratic institutionalization of federal immigration agencies (first the Bureau of Immigration, then the Immigration and Naturalization Service, and now Immigration and Customs Enforcement9) and their physical infrastructure, as well as the figurative and material construction of national borders, and the movement of the detention and deportation authority from the international boundaries into the interior of the nation. Interior enforcement, in particular, creates a form of “eternal probation” for all noncitizens,10 legal or unauthorized, that suggests a long-term surveillance strategy, long after migration, often leading to family and community dissolution, workplace and economic interruption, and the stigma of banishment. By taking the long view of the detention regime, we bear witness to the accrual of flexible state power over noncitizens as well as an enduring partnership with the criminal justice system that mutually reinforces the other.

Immigration’s “Lost Century”

The immobilization and forced removal of persons in what is the United States has deep roots that predate the formation of the Bureau of Immigration in the 1890s and the founding of the nation in the eighteenth century. Unearthing these roots is critical to understanding detention history, including its affinities to prisons and criminal incarceration. Moon-Ho Jung’s Coolies and Cane: Race, Labor, and Sugar in the Age of Emancipation, for example, draws together the state control of chattel slavery in relation to the recruitment and later exclusion of Chinese “coolie” labor, arguing that the two institutions were “inextricably bound,”11 reflecting a transition from laws governing the slave trade to the foundational legal structure managing nonwhite immigrants. Immigrant detention also draws from the heritage of slave labor, the control of free blacks, or the recapture of fugitive slaves. In fact, the control of nonwhite immigrant mobility plays a critical function in labor management, the industrial development of the West, and the establishment of national sovereignty. During the century prior to the federal institutionalization of its immigration authority via the regulation and exclusion of Chinese laborers, the federal government, states and territories, local municipalities, as well as armed mobs in acts of “racial vigilantism”12 excluded and, if need be, captured and removed persons deemed outsiders or undesirables according to local policy or extralegal means. Local laws and customs begat state laws restricting undesirables, as “the status of being poor was as significant as that of alienage.”13 Later this practice would take on a more racist and sovereign turn as forced removal would be applied to large populations “in the way” of but also central to national expansion—Native American nations and black chattel slaves.

Predating the first federal exclusion laws, this colonial and antebellum period is termed by legal scholar Gerald Neuman “the lost century of immigration law (1776–1875).”14 As a “lost” history, it divorces the late nineteenth-century institutionalization of immigration authority from its roots in controlling the mobility of the poor and nonwhite persons as well as early naturalization policy—regulating who can immigrate and later gain citizenship—which beginning in 1790 restricted the acquisition of citizenship to “free white persons.” Racial prerequisites to naturalization produced a racialized migrant marginality that is rarely discussed alongside the mythology of the “nation of immigrants” and lasted in some form until 1952. This foundational liability for nonwhite migrants would influence anti-immigration sentiment and hostility and later would be at the core of enforcement policies.

The immobilization of immigrants, especially as it is tied to deportation, has deep roots and critical connections to postbellum prison reform. Nineteenth-century prison development contributed to the literal and also legal “disabl[ing] of the slave.”15 With slavery and emancipation, captive black bodies generated and produced a legal system that maintained their captivity and hastened their civil and literal deaths. The widespread criminalization of former slaves and other free blacks via Black Codes directly followed emancipation and merged with “reforms” of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century policing and imprisonment methods. Finding roots and parallels in today’s prison and detention systems, Black Codes replaced antebellum Slave Codes, creating avenues for conviction and reenslavement of black bodies under the guise of the prison.16 As Colin Dayan suggests, “The legal nullification of personhood that began with slavery has been perfected through the logic of the courtroom and adjusted to apply to prisoners.”17 A juridical system was also created to establish the marginality and control of nonwhite migrant labor. The nation’s pivotal racial exclusions of Chinese immigrants were tied to slave economies. Jung writes, “As much as the Page Law (1875) and the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) heralded a new era of immigration restrictions in U.S. history, they also marked the culmination of nineteenth-century slave-trade prohibitions.”18 “Coolies,” according to Jung, “were viewed as a natural advancement from chattel slavery and a means to maintain slavery’s worst features.”19

The crystallization of detention law and enforcement under Chinese exclusion and anti-Asian racism flowed from the trajectory of chattel slavery to coolie labor and would be updated in the twentieth century to include campaigns targeted at Mexican immigrants (through their derision and forced removal). A critical prologue, the exclusion and removal of poor persons from local colonial communities, federal Indian removal programs, the capture and return of fugitive slaves, as well as restrictions on free black persons in the United States “foreshadowed,” according to Daniel Kanstroom, “the federal deportation system”20 that would impact Asian and Latina/o migrants. Slavery and the control of free black mobility before and after emancipation, in particular, “were fundamentally related to the development of the post-Civil War deportation system,” making Chinese removal “less strange to the American palate.”21 For example, the Fugitive Slave Law’s procedural elements, which offered disadvantageous legal protection despite providing a day in court in the slave state from which the fugitive fled, were later “adopted by the Congress and accepted by the Supreme Court as legitimate components of the deportation regime.”22 The “lost century” of immigration control, which enveloped slavery and emancipation, was also the foundational century for prison development. The federal government’s control of human mobility and its reliance on the criminalization of nonwhites and noncitizens would help solidify the sovereignty, borders, and whiteness of the nation. In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Asian and Latina/o migrants would play a special role in the nation’s economic and sovereign development as the primary racial targets of immigration enforcement.

Racial Bookends

Asian and Latina/o migrants have been at the center of the majority of U.S. detention and deportation policies and practices since the bureaucratic consolidation of the federal immigration authority in the late nineteenth century. Appearing in nearly all stages of detention and deportation history under a variety of undesirable social constructions, Asian and Latino noncitizens serve as racial bookends in the ongoing history of immigrant detention in the United States. Whether imprisoned in different eras as threats to public health, as military and ideological enemies, as nation-destabilizing refugees, as immigrant terrorists, and, most persistently, as criminals and so-called illegals, Asian and Latino migrants and detainees are at once foundational to the history of immigrant detention as well as emblematic of today’s detention system.

To address these leading racial subjects in the history of U.S. immigrant detention—which also includes a variety of nonwhite and white migrants—it is critical to understand the malleability and productivity of race and racism in the United States, especially how racist animosities are transposed from one social group to another in immigration enforcement. Comparative analysis of the detention system provides one of the best ways to understand this transposition of racial anxieties as they are reflected in the practices of immigration enforcement. Focusing primarily on the highest profile episodes of immigrant detention—for example, on Arab, Muslim, and South Asian detainees apprehended immediately after 9/11 or solely on Japanese and Japanese American internees during World War II—would occlude the broader historical patterns, legal strategies, and social contexts that link various groups of detainees across an entire century. We have to look beyond these extraordinary examples of detention to understand the breadth and centrality of Asian and Latina/o detainees. Moreover, a noncomparative analysis of the immigrant prison system has the potential to reinscribe the very form of exceptionalism that typically frames episodes of immigrant detention, preventing us from viewing the extensive racial genealogy of this carceral institution.

Racialized detention practices, especially when linked to crises in national security, have been treated historically as isolated incidents, masking the institution’s historical patterns and broad, escalating, and nearly unrestrained capacity to detain immigrants. Although crises in national security can vary from decade to decade, the punitive treatment of noncitizens, especially their detention and expulsion, recurs time and again, often gaining authority and legal and social precedent. Understanding the genealogy of racialized episodes of immigrant detention, dating back to the inception of the Bureau of Immigration in the 1890s to today’s post-9/11 detention expansion, is thus critical because these episodes create the precedents that diminish contemporary legal avenues for relief, generate the construction and escalation of the detention infrastructure, and contribute to the enduring mechanisms of criminalization that are attached categorically to racialized groups of immigrants.

The material consequences of detention policy exemplified by historical episodes involving Asian and Latino noncitizens are difficult to bring to light when positioned alongside the tragic and shocking ramifications of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, or, for that matter, other historical episodes that are presented as unique, extraordinary, and without comparison. The domestic and international “war on terror” that ensued post-9/11 marks a recent and sensational period of noncitizen detention. Elevated national security concerns have been used to justify an accumulation of administrative power by the executive branch over detention matters as well as significant increases in the detention infrastructure and new enforcement initiatives. In addition, the war on terror brought a long overdue spotlight to the system of immigrant detention in the United States, which had already been expanding dramatically, although mutedly, prior to 9/11.

Expanded immigration enforcement effected across the board and allegedly targeted at all noncitizens relies on an ongoing reliance and increased tolerance for racial profiling in immigrant policing. As a result, Latina/o noncitizens reflect the primary racial demographic in immigration enforcement for the last three-quarters of a century—today, well over 90 percent of apprehensions, detentions, and deportations involve Latin American migrants.23 Latinas/os have thus shouldered the weight of increased enforcement despite the intensified high-profile attention to Arab, Muslim, and South Asian detainees in the aftermath of 9/11. Contemporary immigration enforcement, reframed as an issue of national security linked to terrorism, has thus masked the patterned and institutionalized practices of noncitizen detention directed at Asian and Latino immigrants for well over one hundred years. This amnesia to the historical contours of domestic immigrant detention would worsen after the international scandals at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, and secret “black sites” used for interrogation of detainees outside the United States. Although Latina/o and Asian Muslims have been directly, often violently, targeted by both the domestic and international operations of the “war on terror,” the ongoing pre-9/11 century of domestic detention is too often overshadowed by this latest episode of immigrant incarceration.

The contemporary period of post-9/11 immigration enforcement is part of a disastrous lineage of detention and deportation programs unfairly removing large, blanket categories of people. Today’s detention practices are reflective of an enduring episode of detention expansion that began in the mid-1990s, was exacerbated by 9/11, and expanded to record levels under the Obama administration, which deported over two million persons. Anti-immigrant discourse dictates that national security is threatened by the very presence of immigrants. In addition, because a great deal of political currency is derived from anti-immigration policies, political leaders from both major political parties have exploited the opportunity to appear tough on crime, immigrants, and terror—targets that today are intimately linked.

Administrative policies that expand detention and deportation draw from and contribute to the overall criminalization of immigrants, accentuating not simply the border separating who remains in the United States and who is deported. The real scale of such processes is amassed by the creation of exploitable social classes inside the United States but outside basic legal protections. In this sense, the noncitizen, much like the criminally arrested or convicted prisoner, is a productive and constitutive factor of our security state, legitimizing its expansion, growing its bureaucracies, funding private for-profit jailers, and drawing support from voters and popular opinion. Because detention episodes involving Asian and Latina/o migrants are recurring factors and have occurred at decisive points in the maturation of U.S. detention policy and its bureaucratic infrastructure, Asian and Latina/o detention history is fundamental to the breadth of the carceral regime and reveals the near boundlessness of executive and congressional power over noncitizen detention.

Historical exploration of Asian and Latina/o experiences shows the primary and persistent role of race in detention history. The malleable and continuous importance of race, racial profiling, and racial animus disrupts the exceptionalism cloaking detention episodes by addressing their extensive historical genealogy, from the foundational enforcement effort against Chinese and other Asian migrants, through the period of transition when Asians and Latinas/os occupied similar racial anxieties, to the crystallization of anti-Mexican immigration enforcement in the mid-twentieth century. Other immigrant-related fears, including fears of foreign ideologies as well as other racially complicated constructions of “white” enemy aliens, also animate detention history. For example, Gary Gerstle links backlashes against white multiculturalism and pluralism during World Wars I and II to the “extraordinary hostility of so many Americans to anarchism, socialism, and communism … leveled at entire populations of immigrants and not just at the comparatively small groups of agitators who resided within them.”24 Even these episodes of noncitizen detention reflected racial contours, as “disloyalty was grounded in a racial character that chronically predisposed these groups to subversion.”25 Gerstle similarly recognizes the fragility of whiteness and belonging for southern and eastern Europeans, especially during the Red Scare. Gerstle writes, “Suspicion fell most heavily on communities of immigrants, especially those who had originated in eastern and southern Europe and who were thought to be vulnerable to Bolshevik propaganda.”26

Although these periods of “rigid emphasis on Americanization and cultural homogeneity”27 reverberated through white ethnic groups, they proved to be temporary and did not pack the sustained intergenerational racial punch of detention episodes involving nonwhites, in particular Asians and Latinas/os. Moreover, it is important to note that the racialized treatment of white ethnic “enemy aliens” and so-called political subversives occurred amid a century of simultaneous surveillance, detention, and expulsion of Asian and Latina/o migrants that did not rest solely on a wartime rationale. The policies and Supreme Court decisions involving Chinese migrants and deportees in the late nineteenth century served as what Eithne Luibhéid terms a “blueprint” for future enforcement policies and technologies,28 wresting detention and deportation authority from the states and conjoining exclusion, deportation, and detention under one broad authority. This would expand throughout the twentieth century, “becoming more centralized, more bureaucratic, harsher, and less forgiving”29 at exactly the time when Mexicans overtook Asians migrants as the preeminent cheap labor source and were targeted for expulsion and repatriated en masse during the 1930s and in subsequent decades.30 Necessitating a period of transition from primarily anti-Asian to anti-Mexican enforcement priorities, the stigma of “illegality” and undesirability was eventually passed permanently from Asian immigrants to Mexican and other Latina/o immigrants. During this interwar period, Mexicans emerged as the prototypical “illegal aliens” dominating categories of noncitizen criminality and becoming the primary targets for immigration enforcement continuing today.

For over a century, the confluence of racism, xenophobia, and the construction of various national crises have cast Asian and Latina/o immigrants as enemies within the nation or at its borders. With diminished legal rights as noncitizens and limited social benefits as racialized subjects, Asian and Latina/o migrants have shouldered the lasting burden of expanding detention policies that rearticulate the boundaries of their citizenship. With immigration enforcement often animated by the rhetoric of “war”—such as world wars, the Cold War, or the “wars” on drugs, crime, and terror—the government’s ability to detain Asian and Latina/o noncitizens for being the carriers of disease, military enemies, refugees, or criminals hinges on their social and legal vulnerabilities, in particular, the government’s abundant methods of denying due process to detainees.

Cumulative Racial Anxieties and Legal Technologies

Central to the federal government’s authority to detain noncitizens and in turn noncitizens’ reduced capacity to protect themselves from such processes are two foundational principles developed through anti-Asian immigration law and policy: plenary power and administrative punishment. Together, they form what has been called the legal blueprint for today’s detention and deportation system. The first, plenary power doctrine, derived from the 1889 Supreme Court case Chae Chan Ping v. United States (also known as the Chinese Exclusion Case), which invokes inherent national sovereignty as the basis for the exclusion of undesirable immigrants.31 The decision, what Kanstroom describes as a “dramatic overstatement” and a “breathless, unequivocal invocation of federal sovereign power,”32 was conjoined shortly thereafter with the Court’s highly consequential pronouncement that deportation from the United States and its attendant process of detention are not punitive. Detention is instead considered legally to be merely an administrative process pursuant to the deportation of undesirable migrants. This legal view, further strengthened by the Supreme Court in Fong Yue Ting v. United States (1893)33 and refined three years after in Wong Wing v. United States (1896),34 both cases involving the deportation of Chinese immigrants, was decisive and served as the foundational and juridical blueprint in the legal construction of Chinese immigrants, detainees, and deportees. Chinese exclusion, according to Roger Daniels, would become the “hinge on which the legal history of immigration turned.”35

These legal decisions, adhered to today, draw on Luibhéid’s suggestion that the early immigration policies, in particular the 1875 Page Law targeting Asian women for exclusion, drew a “blueprint for exclusion” and served as “a harbinger not only of sexual, but also of racial, ethnic, gender, and class exclusions that were codified by subsequent immigration laws.”36 In the nineteenth-century context of anti-Chinese sentiment and despite sophisticated legal defenses by a “ ‘Dream Team’ of elite lawyers of the day”37 providing counsel for Chinese labor interests, the determination that jailing noncitizens and removing them from the country was not punishment for criminal activity but an administrative process separate from punishment had lasting consequences for the legal defense of detainees. According to Kanstroom, “The decision from the Supreme Court was, by any measure, a bombshell. Its repercussions are felt to this day.”38 Administrative detention, or nonpunitive incarceration, remains the legal foundation for the contemporary detention system.

As merely a temporary and nonpunitive stage in the deportation process, immigrant detention does not necessitate the legal protections guaranteed constitutionally to persons charged with crimes or serving clearly defined sentences. Because the Supreme Court ruled that “the order of deportation is not a punishment for a crime”39 and detention is “not imprisonment in a legal sense,”40 detainees are regularly denied myriad legal protections, including guaranteed counsel, access to bond, transparent evidentiary standards, as well as prevention of transfers and changes of venue and provision of religious materials and dietary requirements. Today’s expanding detention system, affecting noncitizens from all over the world but primarily Latin Americans, rests on these century-old judgments and is buttressed by widespread popular notions of “illegality” among migrants today.

Immigrant detention is thus inoculated against critiques of and comparisons to criminal punishment because it is defined otherwise. The nonpunitive construction of immigrant incarceration and deportation obfuscates the widespread popular experience of punishment among detainees and deportees whose lives are at times irreparably transformed. As Justice Brewer wrote in his vigorous and timeless dissent in Fong Yue Ting, “But it needs no citation of authorities to support the proposition that deportation is punishment. Everyone knows that to be forcibly taken away from home and family and friends and business and property, and sent across the ocean to a distant land, is punishment, and that oftentimes most severe and cruel” (emphasis added).41

Technological innovations in immigration enforcement were founded on the legal blueprint imposed on Chinese immigrants and buttressed by regional and national anti-Asian sentiments that were gradually transposed to Mexican and other Latina/o migrants. The early development of the federal immigration authority required new technologies and strategies for enforcement. Many of these strategies began as racial prototypes, originally developed to halt Chinese migration, but then were extended to other racialized populations before being implemented nationally to enforce immigration laws against all migrants. Two of these early technologies were photography and visual examination of arriving migrants as well as the development of the U.S. Border Patrol. Both of these enforcement tools were born out of Chinese exclusion and then later applied to Mexican migrants in the U.S. Southwest.

The use of photographic identity documents for the purposes of immigration control was implemented administratively in 1875 with the Page Act, barring migrants whom authorities deemed were sex workers. The use of this model technology was targeted racially at Chinese women and predated any statutory requirement for photographic identification by nearly twenty years and the introduction of photographic passports by forty years. Instead, it was implemented on a regional and local basis by immigration and customs officials.42 According to Anna Pegler-Gordon, “visually based regulation was part of the process through which immigration policy created and reinforced racial hierarchies.”43 Case files—detailed with photographs for Chinese migrants and with the “barest of data”44 for Europeans—also reflected immigration authorities’ increased concern about nonwhite immigrants. Later, as Asian migration waned due to years of exclusion, and when Mexicans rose to prominence as the United States’ primary form of imported labor, photographic technologies became standard for Mexican migrants in the form of labor identification cards, passports, quarantine cards, border-crossing cards, and other forms of documentation.

A second critical technology was the development of the U.S. Border Patrol, with broad police powers in the national task of immigration enforcement. The Border Patrol, which would play a critical role in the transition from an anti-Chinese operational focus to an anti-Mexican one, was also based on early twentieth-century anti-Chinese immigration concerns. Concerned persons feared that Mexico would be used as a “staging ground” for unauthorized Asian migration.45 Robert Chao Romero argues that “Chinese immigrants ‘invented’ undocumented immigration from Mexico,” utilizing the southern neighbor (and Cuba too) as a “strategic gateway.”46 Immigration enforcement was thus targeted at this flow of undocumented migration prior to the formation of the U.S. Border Patrol. Founded twenty years before the Border Patrol in 1904, the Mounted Guard of Chinese Inspectors was charged with enforcing federal Chinese exclusion legislation along the Canadian and Mexican borders. As an example of this force’s foundational importance, twenty years later, when the Border Patrol was formed in 1924, remnants of this prototype force would be the “first men hired as Border Patrol officers,” according to Kelly Lytle Hernández, making up 24 percent of the initial 104 officers.47

Alongside these swelling technologies of enforcement were related processes for evasion and surreptitious entry. The processes of exclusion, detention, and removal and, in turn, systems to evade those restrictive practices reflect a historic cat-and-mouse game between immigration authorities and migrants—each exerting agency with deep historical roots and contemporary significance. According to Chao Romero, Chinese migrants exploited the detention and deportation systems by bribing immigration officials and swapping deportees who wanted to remain in the United States with migrants who wanted to return to China.48 In short, Chinese returnees entered detention voluntarily in order to be deported surreptitiously home to China. A more notorious example is the exploitation of the interrogation process for Chinese entry after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake destroyed Chinese immigration case files. According to John Park, “They coached one another, falsified documents, bought identities, made up whole new ones, and otherwise misrepresented themselves on a grand scale, so much so that almost an entire generation of Chinese immigrants consisted of ‘paper sons,’ native-born Americans only by deceit and forgery.”49 Whereas anti-Chinese and broader anti-Asian immigration enforcement strategies became models for future exclusions and removals, migrants exploited weaknesses in many of the very same technologies to evade authorities.

The majority of these technologies founded during the era of Chinese exclusion were targeted at containing disease entering the United States through its international ports of entry. Medical detention thus became a primary vehicle for the detention and deportation of Chinese and later Mexican immigrants. The Immigration Act of 1891, which created the federal enforcement bureaucracy—after major restrictions of Chinese entry had been under way for decades—also required that medical examination be conducted by the U.S. Marine Hospital service (renamed in 1912 the U.S. Public Health Service).50 Visual medical examination, guided by racial and class beliefs about white and nonwhite immigrants, intersected with national public health concerns, which often pivoted on racialized presumptions about “troublesome diseases,” such as trachoma or typhus, that were believed to inhabit the bodies and cultures of arriving migrants. Fears of disease and contagion served as ideal ideological justifications for the exclusion or segregation of non- and lesser-white migrants whom Americans feared would contaminate the health and racial composition of the nation. Such “loathsome” diseases were overwhelmingly presumed to be endemic in Asian migrants populating the West Coast. Moreover, this belief justified double standards for nonwhite immigrants in medical examinations, leading to the detention of “diseased aliens.” According to the commissioner-general of immigration in 1903, “The diseases which endanger the health of the American people through alien immigration are distinctively oriental in origin, and that the transportation lines bringing aliens from eastern Europe and from Asia are the ones to be most carefully scanned.”51 Lauded as the gateways for “the nation of immigrants,” U.S. ports of entry merged new bureaucracies of fees, regulations, and fines and served as the nation’s first line of defense against undesirables and as critical sites for detaining immigrants.

Asian migrants entering from the west to California were burdened by countless descriptions of disease and filth. Before disembarking in San Francisco, they were first detained at Ayala Cove Quarantine Station on Angel Island, which predated the western port’s immigration and detention station at the same site by two decades.52 While at the quarantine station and later the immigration station, Asian migrants’ petitions and documents requesting entry or reentry were scrutinized for validity while their bodies underwent medical examination. This applied to returning Chinese migrants with documents and Chinese Americans returning to their nation of birth. Toward the end of Angel Island’s official use, the station’s spatial attributes, once regarded as especially suited for Chinese migrants, rendered practical difficulties after the Immigration Act of 1917 codified the “Asiatic barred zone,” drawing a thick line of exclusion around the continent of Asia. In effect, the consolidation of anti-immigrant legislation accomplished legally what the detention site attempted to achieve spatially.

Along the U.S.–Mexico border, the Bureau of Immigration and U.S. Public Health Service also stepped up efforts between world wars to establish an “ ‘iron-clad quarantine’ against every body entering the United States from Mexico.’ ”53 As with Asian immigrants, race linked Mexicans to constructions of disease and pernicious uncleanliness, as Mexican immigrants contended with what Natalia Molina has called “medicalized nativism.”54 Scientists and public health agents concerned about typhus both exerted and buttressed their authority through the construction of the diseased “alien.” As one Public Health Service doctor wrote in the 1920s, “all persons coming to El Paso from Mexico” were “considered as likely to be vermin infested.” For Mexican border crossers, then, medical detention included additional processes such as being stripped naked, deloused, vaccinated, bathed with “a mixture of soap, kerosene, and water,” and having their clothes and baggage sterilized.55 Even daily Mexican border crossers who worked or studied in the United States had to be sterilized on a weekly basis. Medical detentions occurred at a time when there was not a military threat with which to rationalize the scapegoating or detention of Latino or Asian migrants. While an entire discourse of contagion specifically targeted Asian immigrants on the West Coast,56 for Mexicans, who were exempt from racial exclusion laws and later the racist national quota system, medical rationales were even more critical to the restriction of Mexican immigration. The quarantine and medical detention of border crossers, according to Stern, “became the status quo on the border,”57 lasting nearly twenty years. Such medicalized discourse would reappear in the late twentieth century, when HIV/AIDS was deemed grounds for exclusion, leading to an infamous case of U.S. quarantine of HIV-positive Haitian asylum seekers at Guantánamo Bay Naval Base, some for as long as eighteen months.58 In 2003, Chinese migrants wanting to attend summer school at the University of California, Berkeley, were banned because of fears of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Only about 13 percent of those wanting to attend in 2003 could be accommodated due to limited capacity of Berkeley’s “isolation facility” and the “ ‘volume’ problem” created by the interest in temporary migration from SARS-affected areas in China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.59

Another key category of detention, involving racialized constructions of Asian migrants and Asian American citizens, was the “enemy alien” during World War II. Whereas other enemy nationals during military conflicts were detained en masse—although nowhere near the scale of Japanese and Japanese Americans during World War II—Japanese internment set extraordinary precedents in the detention of citizens. For instance, the federal government also detained enemy aliens during World War I and executed harsh deportation laws that targeted political dissent. Racial conflation in a manner that transcends U.S. citizenship is a common practice in immigration enforcement dating back to Chinese exclusion and is part of the sustained racial profiling of Latina/o communities today. Regardless of whether they have citizenship or proper documentation, suspicion easily prevails in the policing of nonwhite migrants, underscoring their constant vulnerability. As Pegler-Gordon writes of the Chinese exclusion era, “Immigration inspectors generally saw little difference between Chinese laborers and ‘respectable’ members of the exempt classes, treating them all with the same lack of respect.”60

Producing a sense of “perpetual foreignness,” racialized fears of migrants and citizens are animated during wartime, legitimizing the expanded powers of the federal branches of government and often exceeding the responses to health, economic, or other national security emergencies. Positioned as threats to national security during times of war, foreign nationals from countries locked in military conflict with the United States are deemed “enemy aliens” (or, in today’s terms, absent of an enemy nation, “enemy combatants”) and are subject to the emergency war powers of the executive branch, which has resulted in mass incarcerations of foreign nationals in the United States and numerous other abuses. As such, Japanese and Japanese American enemy aliens, once the paradigmatic victim of detention during military conflicts, prepared the infrastructure and legal groundwork for future detentions of racialized migrants. This includes the racialized detention practices used against Arabs, Muslim, and South Asians as well as harsh treatment and sustained suspicions targeted at their citizen counterparts after 9/11.

Racial anxieties and nativism are paramount in these eras of racial incarceration. The wartime relocation and incarceration of Japanese and Japanese American citizens from December 7, 1941, through September 29, 1947, served as a notorious application of presidential emergency war powers. The racial construction of Japanese residents as state enemies blurred the distinctions between citizens and noncitizens. As law professor David Cole explains, “The close interrelationship between anti-Asian racism and anti-immigrant sentiment made the transition from enemy alien to enemy race disturbingly smooth.”61 So-called enemy aliens from Italy and Germany were also detained—almost 3,000 in 1942—but they did not include large numbers of U.S. citizens, and they were not held in proportion to their numbers enumerated on the federal “alien registration” lists. That is, Italians and Germans outnumbered Japanese immigrants threefold (for Italians) and sixfold (for Germans). They also received individual review of their cases, resulting in parole,62 which the Japanese did not. Over thirty years later, the federal Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, appointed in the early 1980s to review the “facts and circumstances” surrounding Japanese internment, concluded that “The broad historical causes which shaped these decisions were race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership.”63 Just as anti-Asian racism played a central role during military conflict and affected citizens, one could argue that 9/11 detentions were founded on the same elements blamed for the Japanese internment. Race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership were also key to these racially targeted enforcement programs, drawing on a legacy of anti-Asian racism.

Consolidation of Racialized “Illegality”

The shift in focus from anti-Chinese immigration enforcement to anti-Mexican enforcement was a gradual one, in which Chinese and Mexican migrants in the United States occupied similar geographical spaces and popular anxieties and were co-targets of immigration enforcement initiatives, mutually reinforcing their racial otherness and its centrality to immigration policy. Overall, racially targeted exclusion legislation and the enforcement policies and procedures detecting, detaining, and deporting Chinese immigrants contributed to the iconic rise of the Mexican “illegal” immigrant. According to Lytle Hernández, the new racial norm in border enforcement “accompanied a slow turn away from policing unsanctioned European and Asian immigration as policing Mexicans emerged as an expedient and cost-effective strategy for U.S. immigration law enforcement.”64 During the transition to focusing on Mexican undocumented migration, enforcement became primarily and binationally focused on the U.S.–Mexico border, first as a site for undocumented Chinese entry and then focused on Mexican “illegal” entry.65 In turn, once it was the racial target of U.S. immigration enforcement, the devalued status of Mexicanness became further discounted by class, sex, gender, occupation, language, access to lawyers, and other vulnerabilities in due procedural rights inherent in the detention and deportation processes.

In the U.S.–Mexico borderlands context, the critical divide in legal status laid bare by blueprint legislation and enforcement technologies was steadily “Mexicanized.” Chinese presence in the binational U.S.–Mexico borderlands, however, was a key factor in the growing focus on Mexican migration and emigration. Dual anxieties about Chinese and Mexican undocumented migration and parallel enforcement bureaucracies in the United States and Mexico converged binationally on these two populations. Just as they had in the United States, despite initial recruitment of Chinese laborers, anxieties about public health and economic competition caused by the presence of Chinese migrants led to Mexico’s passage of federal legislation and the creation of immigration bureaucracies and authorities—Servicio de Migración and the Servicio de Inspección de Inmigrantes in the early twentieth century. The Mexican government was particularly concerned that Chinese migrants served as “a major precipitating factor for Mexican emigration” to the United States, and as a result, tougher, more restrictive laws followed in the 1920s, limiting immigration and emigration in a multiagency effort that included public health and sanitation services.66

The competition from and harsh treatment of Asian migrants in Mexico pushed a dual stream of Mexicans and Chinese north to the United States, leading to a convergence of racial immigrant policing. For example, Chinese migrants exploited the “racially liminal”67 border zone to disguise themselves as Mexicans crossing legally, and therefore with fewer restrictions, into the United States. Fears of such fraudulent “legal” entry aided in the transposition of technologies designed for Asians to be used to regulate Mexicans. As Pegler-Gordon states, “Mexicans could not be allowed to pass freely, since they might not be Mexican.”68 Organized anti-Chinese sentiment in Mexico, or Sinophobia, also funneled migrant Chinese, once the second largest immigrant community in Mexico by 1926,69 toward entry without inspection. Whereas Chinese exclusion in the United States redirected Chinese migration to Mexico, anti-Chinese sentiment in that country drove Chinese migrants back to the United States—many to be detained and deported by U.S. taxpayers70—in what Chao Romero terms a “dark and forgotten chapter of Mexican history.”71

Immigration enforcement from the 1920s through the 1930s reflected a complex regional and binational formation constituted by Southwestern racial and class politics. Lytle Hernández writes, “The Border Patrol’s turn toward policing Mexicans, in other words, was much more than a matter of simply servicing the interests of agribusiness in capitalist economic development. It was a matter of community, manhood, whiteness, authority, class, respect, belonging, brotherhood, and violence in the greater Texas–Mexico borderlands.”72 The earliest incarnations of the Border Patrol relied on a decentralized apparatus that permitted regional forms of enforcement that hastened the transition to Mexico as the primary operational focus. Even bureaucratic attempts by the U.S. government to nationalize its border enforcement strategy led to further entrenching regional, in particular anti-Mexican, concerns. For example, when the Border Patrol Training School (BPTS)—originally called the El Paso District Training School—was formed in 1934, its Texas location was a key structural factor in the further Mexicanization of immigration enforcement and detention and deportation. According to Lytle Hernández, “the establishment of the BPTS is most remarkable in the ways that it centralized the Texas–Mexico borderlands in the making of U.S. immigration law enforcement.”73 The Texas model of immigration enforcement, with its long history of anti-Mexican violence, would become the standard for national enforcement training.

In the U.S. Southwest, earlier concerns about Asian and other migrants transmigrating via Mexico gave way to a dominant and representative focus on Mexican border crossers in this region. As such, by the end of the 1930s, the operational focus of the Border Patrol in the entire U.S.–Mexico borderlands—from Texas to California—focused on Mexicans,74 eclipsing other targets of migrant enforcement. The “Mexicanization” of enforcement became a national strategy that shifted resources such that “policing Mexicans [became a] proxy for policing unsanctioned border crossers.”75 As Daniel Kanstroom states, “Mexican workers eventually became the prototypical illegal aliens against whom much of the machinery of the deportation system has been directed.”76 As Mexicans were equated with unlawful migration in enforcement priorities and popular sentiment, more sweeping anti-Latina/o fears reached other Latina/o migrants and U.S. citizens, lasting for decades, if not permanently. Possession of U.S. citizenship, just as it proved a weak protection for Chinese Americans and Japanese Americans reentering the country or fighting internment during World War II, was also an insecure mechanism for protection from immigration authorities utilizing racially targeted policing and detention practices. During the twentieth century, as the demographics of Latina/o migration came to include a wide variety of Latin American migrants, Latinas/os would remain the exemplar of immigrant detention and deportation even though the U.S. government’s power over noncitizens was transcendent and affected all migrants.

Multiple racial fears about Mexican criminality, economic competition, as well as health concerns in the Depression-era 1930s led to a nationwide repatriation campaign that effected the removal and voluntary departure of a conservative estimate of a half-million Mexicans and their children, many of them citizens. Mexican “illegality,” which was established criminally with the offense of undocumented entry in 1929,77 would come to dominate public anxieties for the next three-quarters of a century. It would be conjoined with the economic offense of being a public charge, widening Mexicans’ vulnerability to detention and deportation. By the 1930s, Mexicans were the largest or second largest group of immigrant detainees in several criminal categories: “narcotics classes,” the “immoral classes,” those convicted of “crimes of moral turpitude,” and “aliens who were criminals at the time of entry.”78 Mexican criminality was distinguished from Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) suspicions of “enemy aliens” or ideological subversives, and instead, Mexicans occupied the majority of anxieties and detention spaces for criminal “undesirables.”

Following the 1930s “decade of betrayal,” concerns about Mexican immigrant criminality would lead to record-setting detentions and deportations throughout the 1940s and 1950s.79 By 1954, Mexican deportations represented 84 percent of all deportation proceedings, and Mexican immigrants were the largest national group in ten of the thirteen deportation categories listed in the INS annual report. The remaining three categories were noncriminal reasons for deportation.80 On June 9, 1954, the INS initiated what was officially called Operation Wetback, a nationwide deportation campaign to apprehend, detain, and deport Mexican nationals. The operation led to the largest number of persons ever held in detention by the INS in a single year, at over one-half million.81 The mass expulsion of Mexicans, announced in 1954, was actually a culmination of a decade of bilaterally coordinated racial expulsion of Mexicans.82 Although Operation Wetback resulted in outrage from Mexican American communities and organizations regarding harassment of citizens, the breakup of families, and widespread fear of law enforcement, the INS hailed Operation Wetback a huge success. “For the first time in more than ten years, illegal crossing over the Mexican border was brought under control” after “the backbone of the wetback invasion was broken,” proclaimed the INS commissioner in 1955.83 Mexicans indeed represented the “backbone” of immigration concerns, eclipsing other migrants, detainees, and deportees in the promotion of national security through immigration enforcement.

Prior to World War II, domestic security policies grounded in the opposition to communism permitted the detention and deportation of migrants who were, for ideological reasons, considered threats to national security. Cold War iterations of such policies in addition facilitated the arrival and official acceptance of refugees fleeing communist nations. On the heels of ideological shifts in Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean, U.S. refugee policy had profound effects, both positively and negatively, for Asian and Latino refugees and asylum seekers. In particular, the humanitarian intent of international refugee policy fell victim to Cold War geopolitics, leading to a massive expansion of detention facilities specifically suited for detaining and discouraging refugees displaced by U.S. military and economic involvement abroad.

In the 1980s, for example, the individual and categorical detention of Asian and Latino asylum seekers was a distinguishing feature of the decade, set in motion in 1980 when 125,000 Cubans fled Cuba through the port of Mariel. In addition to Southeast Asian refugees settling in the United States since the U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam, roughly one million Salvadoran, Guatemalan, and Nicaraguan refugees entered the United States during the decade, fleeing political upheaval and violence that was maintained by U.S. intervention in Central America.84 The refugee exodus fueled a racial panic about Asian and Latino refugee streams that were feared to be nonwhite, criminal, ideologically left, and diseased, leading to distinct policy changes that affected the detention infrastructure, especially after the attorney general ordered in 1981 that all would-be refugees be detained until the final adjudication of their asylum cases.85 The result was an expansion of contracted nonfederal facilities all along the U.S.–Mexico border and a reopening of a federal facility once used to detain Japanese Americans.86 Encumbered with pervasive allegations of human rights abuses—from denial of legal counsel and translated legal material to invasions of private correspondence and sexual abuse—the newly expanded detention infrastructure facilitated Cold War foreign policy objectives defined differently for various countries of origin, resulting in wildly differing results for asylum cases and increased undocumented Central American migration. During the period when immigrants from Asia and Latin America came to dominate most categories of authorized and unauthorized migrants, ideological fears dovetailed with embedded racial fears.

While asylum seekers were being detained at ports of entry in the 1980s, domestic criminalization and detention policy initiatives established with the “war on drugs” shifted the enforcement focus inside the nation to “criminal aliens.” Detained for having been convicted of deportable offenses, “criminal aliens” represent the largest share of all immigrant detainees today. Any noncitizen, either documented or a lawful permanent resident, can be detained as a “criminal alien” and placed in deportation proceedings. Constituting what border expert Timothy Dunn called a “historic change in INS detention practices,”87 the increased detention of “criminal aliens” resulted from the reclassification and expansion of deportable crimes such as drug or gun trafficking, mandatory drug sentencing, and the reduction of legal avenues for relief from detention.

Because any noncitizen is potentially at risk for detention and deportation for having committed one of an ever-increasing list of deportable offenses, there is a cross-section of immigrants occupying this detention category. However, the largest group of immigrants, Mexican nationals, suffer disproportionately from “criminal alien” enforcement. Like African Americans, Mexican and Mexican American communities are already targeted for criminal enforcement of drug crimes, contributing to the massive prison expansion occurring nationwide. Such criminal enforcement has a direct effect on increases in detention, as noncitizens convicted of deportable crimes are placed in detention and deportation proceedings at the completion of their criminal sentences.

A forerunner to the detentions stemming from the “war on terror,” this pre-9/11 period in detention growth in the 1990s transpired by means of a combination of new legislation that targeted immigrants by reducing their due procedural rights, as well as the reintroduction and codification of “national security” in the wake of foreign and domestic terrorism in the mid-1990s. Two laws passed in 1996 in the wake of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing dramatically increased noncitizens’ vulnerability to detention and deportation. The Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act,88 enacted near the one-year anniversary of the Oklahoma City bombing, was drafted as anti-terrorism legislation but instead had its greatest impact on noncitizen criminal offenders, making them easier to deport and mandating their detention pursuant to their deportation. In addition, Congress passed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act,89 elaborately facilitating “criminal alien” detention through a sweeping denial of due process to noncitizens. These laws together are responsible for the pre-9/11 tripling of immigrant detention that occurred in the 1990s and set the stage legally for the massive deportation efforts of Presidents Bush and Obama and potentially Trump. The ongoing focus on immigrant criminality, typified by Latina/o “illegality,” has maintained Latinas/os’ centrality to the institutions of immigrant incarceration. Detention and deportation, according to Kanstroom, “evolved to become primary legal means to regulate this movement of people.”90 The demographic significance of Latinas/os, their iconic status as “illegals,” and their racially targeted profile for enforcement is both a contemporary and historical condition. Even today, Latinas/os represent a majority of persons sentenced to federal prison terms, buoyed primarily by immigration-related criminal offenses, such as undocumented entry and reentry and alien smuggling. These developments demonstrate the view of Latinas/os as the norm in immigration enforcement that also spills over into criminal law.

As an institution, immigrant detention reflects a variety of historic consolidations of legal, administrative, and generally nationalist state power and technologies over immigrants, especially nonwhite immigrants. This brief historical sketch of Asian and Latino detention episodes and paradigmatic categories of detainees outlines the previous century of immigrant-related national security crises in which detention and deportation served as the federal government’s solution to a variety of social, political, and military anxieties. Various Asian and Latina/o migrant groups were central figures in this history of immigrant incarceration and were both foundational to and exemplary of today’s detention system.

Anti-Chinese exclusion and deportation policies produced malleable racial fears and practices that could be transposed onto Mexican and other Latina/o migrants by means of the detention and deportation regimes. Asian and Latina/o detention should be understood relationally and in the broader racial and historical context that includes other white and nonwhite detainees. Nevertheless, this chapter concentrates on Asian and Latina/o detention episodes because these periods bookend the long century of immigrant incarceration in which Asian and Latina/o detainees appear in detention history persistently and according to a variety of racial logics—as threats to the public health of the nation, as military and ideological enemies, as immigrant terrorists, and as criminals and “illegals.” Early, contemporary, and other critical manifestations of the federal detention infrastructure were aimed at these two groups, locating them inside a muddy juridical borderland, a nexus where Asians and Latinas/os overlap legally and historically. Even though many of the legal precedents and enforcement technologies developed initially through anti-Asian immigration enforcement and strengthened through the policing of Latina/o migrants can be applied to all noncitizens in the United States, racially targeted strategies of enforcement have been persistent tools of the federal government when national security has been deemed at risk. None of the foundational categories of detainees explained here are meaningless social categories of bygone eras. They are productive instruments of enforcement, ready to be retooled, rearticulated, and re-deployed for new threats to national security.

Merging Incarcerations, Merging Technologies

According to Angela Davis, “the prison industrial complex is much more than the sum of all jails and prisons in this country. It is a set of symbiotic relationships among correctional communities, transnational corporations, media conglomerates, guards’ unions, and legislative and court agendas.”91 Immigrant detention is invigorated by a parallel statecraft that simultaneously bolsters the nation through immigrant criminalization, policing, and enforcement. By engaging immigration enforcement with the carceral state, we learn that in the shadow of practically unchecked state power over prisoners is a flexible, biased, productive, and deeply advantageous state power over immigrants. These two forms of governmental authority are good neighbors. They share infrastructure, legal and discursive technologies, and tools of enforcement and punishment. Drawing from the same sources of criminality, such as the “war on drugs,” the detention and prison systems flow into each other—each system and its laws producing bodies for the other’s open beds. The detention and prison systems can be used sequentially, exhausting juridical and procedural advantages before switching to the other, especially if prosecution in either system is difficult to accomplish. And today, both carceral systems have national security and anti-terrorism technologies at their disposal. The connective tissues between prisons and immigrant detention as well as the tensions and disjunctures are characteristic of what Juliet Stumpf has termed the “crimmigration crisis.”92 Although it might be useful, especially for the sake of anti-prison and anti-detention collaboration, to stress the affinities between prisoners and detainees, it is important to also note the critical and sometimes insidious nuances that separate these two forms of incarceration. When it comes to prisons and detention, the devil is in the details.

The criminalization of African American and Latina/o persons, of course, as well as persons not possessing citizenship, is key to the expansion of both systems. In California, for example, African Americans and Latinas/os make up two-thirds of the state’s 160,000 prisoners, and 25 percent are noncitizens.93 Nationwide, African Americans are the majority of county, state, and federal prisoners,94 and due to changes in enforcement and adjudication of immigrant crimes, noncitizens represent the primary source of federal criminal enforcement and federal court dockets. Crime and criminals, we know, are political constructions, unfixed and produced through law and policy, popular discourse, racially targeted policing, and various forms of social deprivation. According to Davis, poor people and nonwhites, or persons both poor and nonwhite, “are sent to prison, not so much because of the crimes they may have indeed committed, but largely because their communities have been criminalized.”95 Prison scholars have articulated with clarity the variety of legislated criminal activities that fill prison beds: “and it was the new beds,” writes Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “rather than court commitments, that led to the system’s growth.”96 Racial profiling, mandatory sentencing, three-strikes legislation, drug and gang enhancements, parole constraints that lead to recidivism, and growth in capacity contribute to what Gilmore calls the “criminal law production frenzy.”97 For immigrant detainees, a similar invention, the aggravated felony (via the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988), also established an arbitrary list of crimes, routinely expanded each decade, that is tailor-made for immigrants, including lawful permanent residents. Aggravated felonies, which are applied retroactively (meaning one’s older offenses, after time is served, and even those that predate the invention of aggravated felonies, are also deportable), include a long list of nonviolent crimes and nonfelonies, that for immigrants-only trigger deportation proceedings and mandatory detention. These crimes—including shoplifting, illegal gambling, passing bad checks, tax fraud, or possession of small amounts of controlled substances—are sometimes called among immigrant advocates “aggravated misdemeanors.” Misdemeanors at state or county levels, for example, can be treated as aggravated felonies in deportation proceedings. For immigrants, then, “it’s one strike and you’re out,” and judges and juries in criminal proceedings are knowingly and unknowingly deciding immigration cases even before they become immigration cases. Politically constructed crimes or arbitrary sentencing based on some crimes and not others similarly entrap nonwhites and the poor in the criminal system as well as noncitizens in detention. With aggravated felonies, it is not immigrant criminality that has risen but “illegality” itself, as policy makers create new ways to be illegal and more severe consequences for this man-made status.

The plea bargain in criminal court, in particular, has a special and shifting relationship with aggravated felonies in the immigration courts. Similar in ways to criminal sentence enhancements, aggravated felonies are also determined by the length of a sentence in addition to the offense’s arbitrary listing, further conflating a range or multitude of infractions with deportable felonies. Any criminal sentence of a year or longer for a noncitizen is a deportable offense, even if it suspended and time in jail is never served. And because 90 percent of all criminal cases are closed by way of plea bargain,98 many immigrants and legal permanent residents may be consenting unknowingly to long-term detention and deportation—with lasting effects far outside the scope of their criminal convictions. With this vulnerability in mind, the then INS, prior to 9/11, worked in concert with prosecutors to make sure that criminal sentences, even if suspended by a judge or reduced through plea bargaining, met the expanded range of aggravated felonies. In May 2000, for example, the Atlanta District Office of the INS issued a letter to all district and U.S. attorneys in Georgia explaining how to facilitate through the courts the detention and deportation of criminal aliens. The letter instructs, “If possible do not plea bargain an Aggravated Felony down to a non aggravated felony.… This is important to assure the alien[’s] swift removal and the sixteen level increase [in sentencing penalty] if he returns.”99 The letter further noted that immigrants may attempt to lower the sentence to eleven months, to which the letter advised, “Try to avoid this, by reducing the sentence the alien may avoid removal.”100 Immigrant lawyers nationwide were, of course, upset, calling the letter “despicable,”101 as the memo illustrated the increasing pressure to link activities in the criminal system to punishment in the immigration system.

The Supreme Court considered this merger of plea bargains in the criminal system and its consequences in the immigration court system in Padilla v. Kentucky (2010). In a decision written by outgoing justice John Paul Stevens, the Court ruled that noncitizens had a right to competent counsel in a case involving incorrect legal advice surrounding a plea bargain that triggered deportation. On the one hand, many advocates viewed the decision as an expansion of the rights of immigrants in criminal courts. The case demonstrated that deportation was a special consequence of the criminal plea or judicial decision, indicating immigration norms entering into the realm of criminal norms. On the other hand, for most noncitizens in deportation proceedings, who might use such a defense, fewer than one in eight have legal counsel, as it is not provided in the immigration court system, and as a result, few cases presenting such a defense would ever be litigated.

Discursive inventions and new legal categories of personhood created in the criminal and detention systems in order to facilitate punishment are coupled with the arbitrary invention of forms of criminality. In the criminal court system, one might think of the “vagrant,” the “gang member” in prison and on the streets, the repeat offender, or others. In detention and deportation, we might consider “aliens ineligible to citizenship,” “enemy alien,” “suspected terrorist,” “enemy combatants,” or “illegals.” These legal neologisms, a term borrowed from Jonathan Schell, are utilized for many purposes: to criminalize and stigmatize particular social groups;102 to justify the maltreatment of detainees and prisoners; and potentially to extend or remove provisional rights from the accused or incarcerated, by marking them as different from existing legal categories. According to Gilmore, “Politicians of all races and ethnicities merged gang membership, drug use, and habitual criminal activity into a single social scourge, which was then used to explain everything form unruly youth to inner-city homicides to the need for more prisons to isolate wrongdoers.”103 Similarly, new detention categories for noncitizens are stretched to include U.S. citizens, to confound legal protections for detainees, and to shield government liability.

Legal neologisms are a fundamental part of the detention process. Consider, for example, the widely used term “illegal,” which at once refers to undocumented migrants, is a popular reference for Latina and Latino noncitizens, and unequivocally enunciates criminality. Many undocumented migrants, while unsparingly referred to as “illegals,” have technically not been charged or tried for the misdemeanor of first-time unlawful entry. As such, these persons have not received the procedures, rights, or forms of relief basic to criminal law that would determine such a status. Prior to the George W. Bush administration, unlawful entry was rarely pursued criminally and was more useful as a threat to encourage repatriation or voluntary removal. Under Bush, Obama, and now Trump, the charge of unlawful entry and reentry dominates federal court dockets, demonstrating the political production of criminality. It is also important to note that roughly one-half of so-called illegals never entered the United States unlawfully in the first place and have instead allowed their authorized entry status to lapse. This is not a violation of the criminal code, and if such persons were processed for removal, they would be tried in immigration court, where they have minimal rights in comparison to the criminal court system.

There is a danger, however, in overstating the rights of the criminally accused in relation to immigrants in deportation proceedings as evidenced by the mammoth prison industrial complex. The point isn’t that “illegal” is a false term, masking innocence and thus serving as a counterpoint to the guiltiness of some fabled “real” criminal. The larger point is that the term “illegal” is a popular racist term that parades as a legal one. With all its baggage and the criminalization, racism, and the harsh treatment that flows from the term, it is an irony that the category “illegals” refers to persons who have never been adjudicated nor permitted access to a legal defense. Migrants’ generic “illegality” is nonetheless viewed as an inherent and self-evident quality indicative of character and future behaviors. Society is wary of extending rights to the undocumented (such as the right to purchase health care under the Affordable Care Act), fearing that these might “reward” their dubious “illegality.” Moreover, consideration of the economic, political, social, or historical factors explaining one’s “illegal” presence is unnecessary because, like the criminal supposedly deserving of punishment, the “illegal” has already been judged and juried, and his or her body has already been marked as undesirable.

Legal neologisms and euphemisms such as “illegal” proliferate across detention history. The term “illegal alien” though today commonly synonymous with Latina/o immigrants, particularly Mexican immigrants, was first applied to Chinese immigrants present or attempting to enter the United States after passage of racial exclusion laws beginning in 1875. Chinese migrants became what Erika Lee calls “the first ‘illegal immigrants,’ both in technical, legal terms and in popular and political representations.”104 Already racialized as socially inferior and unassimilable and therefore inadmissible for a broad range of reasons, Chinese migrants were accused persistently of surreptitious entry and other legal technicalities such as not registering as a lawful migrant under the Geary Act (1892) and thus endured lengthy detentions for months and even years to meet the rigorous and racist standards for Chinese entry.105

The merging “crimmigration” system is replete with legal constructions of personhood or crimes that mark and stigmatize the incarcerated, leading to the denial of juridical rights, such as access to counsel or ability to counter or offer evidence, long-term isolation, horrendous conditions (often needlessly leading to death), and, of course, deportation and the separation of families. These legal constructions are punitive. However, in areas of detention and criminal law, they are often legally defined as nonpunitive and noncriminal or simply not defined at all and are productive in their ambiguity. Furthermore, something is clearly afoul when lying about your Social Security number on a Jack-in-the Box employment application amounts to the federal crime of “aggravated identity theft”106 or a deportable “crime of moral turpitude.” Similarly, the harsh punishment of solitary confinement can be equally troublesome, when for cosmetic and juridically significant reasons it is referred to as “disciplinary confinement” or “administrative segregation.” As Dayan writes, “Prisoners’ crimes no longer explain their treatment; rather, society is inventing the criminal, creating a new class of the condemned.”107 These invented categories effect stealth punishments on prisoners and detainees and evade already compromised defensive capacities. They expand prosecutorial advantages, deny relief for detainees and prisoners, and, in many cases, shield various levels of the state from liability. More than isolated abuses of government language and terminology, these technologies of power are ongoing practices possessing consistency, flexibility, and meaning in both immigrant and criminal court systems.

The resulting punishments for aggravated felonies, it must be noted, occur after time is served by noncitizens for the original offense in the criminal system. Further, because immigrants are often considered flight risks, they are subject to increased rates of pre-trial detention in their initial criminal cases and to postsentence detention, as they are transferred from criminal imprisonment to immigrant detention.108 This second helping of punishment—of detention and likely deportation—occurs because of the simple, unchallenged, and nineteenth-century legal fact that detention and deportation are not considered punishments for crimes (although they directly and mandatorily flow from them). Detention and deportation quite simply are not punishment, just like transferring a prisoner is not punishment, and harshly interrogating a suspected terrorist is not punishment. Detention and deportation are not double jeopardy, they require no legal counsel, and detention is not jail time. And although detainees remain apart from accused or convicted criminals in terms of their judicial rights, the majority of ICE detainees are housed in the same unsafe and deadly conditions with the general population of prisoners at state and local jails with intergovernmental agreements with ICE.109