Pharmacokinetics and Toxicokinetics

Kannan Krishnan1,2 and Sandrine F. Chebekoue2, 1Risk Sciences International, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2University of Montreal, Montreal, QC, Canada

Abstract

The level of active form of a chemical in target tissue is of prime importance in determining responses in toxicological studies, and depends upon the processes of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME). The characterization of ADME in biota is referred to as pharmacokinetics (PK); when it is conducted in the range of doses causing toxicity it has been referred to as toxicokinetics (TK). Since repeated measurement of chemicals and their metabolites in all treated animals is not possible, PK parameters and models are used for estimating them. These PK models range from simple, one-compartmental model to complex physiologically based models. A PK parameter, namely elimination half-life (t1/2), is key to the understanding of the amount remaining in the body after each dose and thus of direct use in determining optimal time intervals between doses. Such PK data are also critical in planning future/supplementary studies by different routes or in different species. This chapter presents the basic PK principles and models, with emphasis on their critical role in designing and interpreting toxicity studies.

Keywords

Pharmacokinetics; toxicokinetics; PBPK modeling; dose metrics; absorption; metabolism; distribution; excretion

Introduction

The interpretation of the outcome of in vivo toxicological studies can be challenging when the tissue response is analyzed as a function of administered dose (i.e., dose in mg/kg/d) or exposure concentration (e.g., chemical concentration in dosing solution or exposure medium). The biological responses are more closely related to the concentration of the active form of the chemical present in the target tissue, rather than the amount administered to the animal. The critical importance of the relationship between tissue (or blood) concentrations and tissue responses in exposed organisms has long been recognized in pharmacology and drug development.

In toxicology and risk assessment, the target tissue dose or the internal dose that most closely relates to an adverse response is referred to as a dose metric. Consistent with the current understanding of the mode of action, a dose metric reflects the intensity and level of the biologically active form of a chemical (i.e., parent chemical or metabolite(s)) in a target tissue (or a surrogate matrix such as blood) for a specific duration. Here, the intensity refers to peak, average, or integral measures, whereas the level refers to concentration or amount; the duration corresponds to an exposure time frame of relevance, for example, instantaneous, daily, lifetime, or a specific period during development (such as exposure window corresponding to a particular gestational event). Thus, a variety of dose metrics could be of potential relevance in interpreting tissue response data for a given chemical. Typically, these include the maximal concentration (Cmax), the area under the concentration versus time curve (AUC0-t), or the time-averaged concentration (Cav) of the parent chemical or metabolite(s) in the blood (plasma) or a specific tissue. The experimental measurement, or model-based calculation, of such dose metrics for interpreting toxicity studies is facilitated by pharmacokinetics (PK) and toxicokinetics (TK).

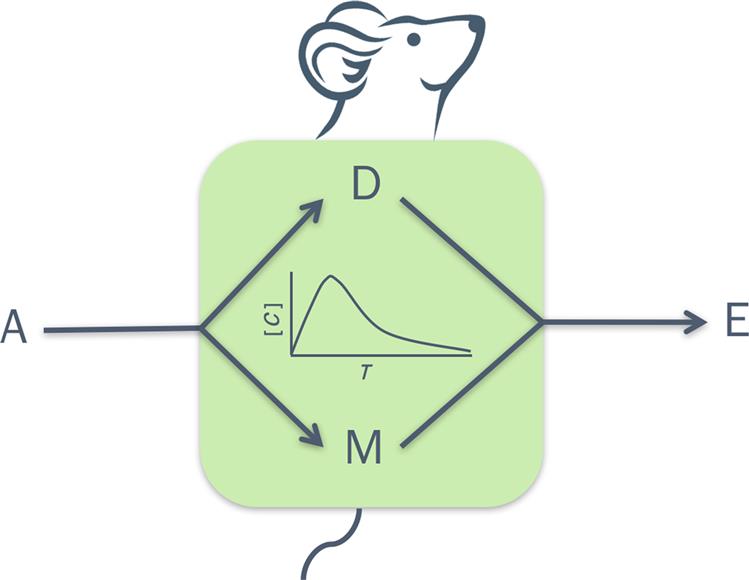

PK involves the study of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) in view of characterizing the time-course of the level of parent chemical or its metabolite(s) in biological matrices. TK is synonymous to PK but the latter term is used when PK principles are applied to toxicants or when kinetic data for therapeutic agents are collected and analyzed at doses that elicit toxicity. In essence then, both PK and TK are fields of study that relate to kinetics, which refers to the change in one or more variables as a function of time.

This chapter presents the basic principles and models used for characterizing the PK and TK of chemicals in experimental animals, with emphasis on their critical role in designing toxicity studies. For more elaborate mathematical treatment of the subject as well as for more complex modeling approaches, the reader is referred to specialized textbooks and monographs on this subject matter (see Further Reading).

Pharmacokinetics: Processes and Determinants

The dose metrics of relevance (e.g., AUC0–t, Cmax) in interpreting response data from toxicological studies depend upon the competing processes of ADME. The time-course of the blood and/or target tissue concentration of a substance or its metabolite(s) in the exposed organism depends upon the mechanism, magnitude, and rate of each of these processes (Figure 3.1). These processes as well as the underlying mechanisms are discussed in detail in Chapter 2: Biochemical and Molecular Basis of Toxicity. The following paragraphs then focus on the quantitative aspects of ADME, highlighting their key mechanistic determinants.

Absorption

Absorption is the process by which the chemical in the dosing solution or exposure medium moves across the biological membranes to get into systemic circulation. Depending upon the purpose of the study, the chemical may be administered by a variety of routes such as dermal/topical, oral, intraperitoneal (ip), intramuscular (im), intravenous (iv), pulmonary (inhalation), or subcutaneous (sc) (Figure 3.2). An iv administration does not comport an absorption phase since the chemical is introduced directly into systemic circulation. For all other routes of administration, the kinetics of absorption is dependent primarily upon the route-specific rate of absorption and bioavailable fraction.

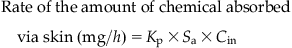

For the dermal route, the flux of a chemical through a membrane following passive diffusion from the immediate environment (e.g., water) can be computed according to Fick’s first law, as follows:

(3.1)

(3.1)where Cin is the applied concentration (mg/mL), Kp is the membrane permeability coefficient (cm/h), and Sa is the exposed surface area (cm2).

The value of Kp reflects the relative importance of both transcellular (lipidic) and paracellular (movement through the water-filled gaps between adjacent cells) transport of chemicals.

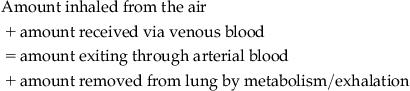

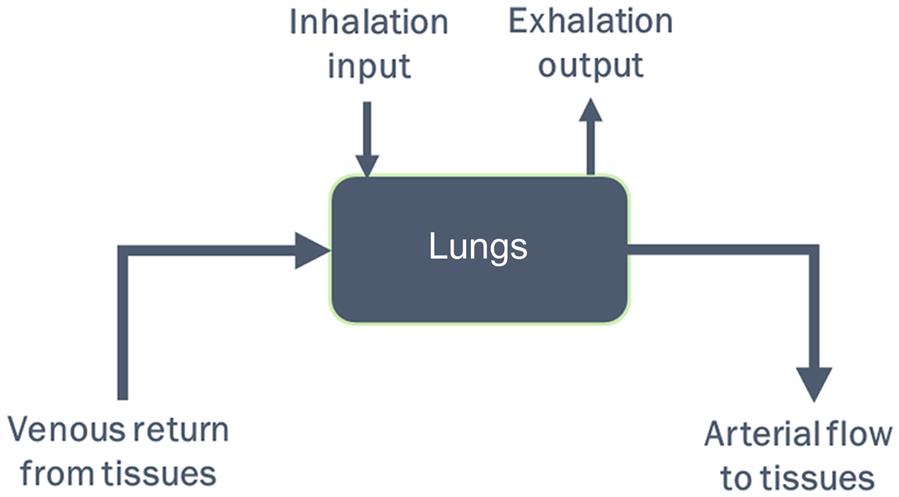

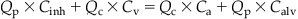

For the inhalation route, the concentration of a chemical in alveolar space and arterial blood, at any time, depends upon the total input and output (or loss) from the lung compartment. Figure 3.3 illustrates a simple case of a volatile organic chemical (e.g., toluene) that equilibrates quickly between alveolar space and blood and for which there is no significant metabolism or storage by the lung tissue. The mass conservation in this case can be written as follows:

(3.2)

(3.2)

Notationally,

(3.3)

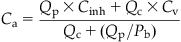

(3.3)where Ca is the arterial concentration, Calv is the alveolar air concentration, Cinh is the inhaled concentration, Cv is the venous blood concentration, Qc is the cardiac output, and Qp is the alveolar ventilation rate.

Since the lung equilibrates vapor between alveolar air and blood, the alveolar concentration and arterial blood concentration are related by the blood:air partition coefficient (Pb), that is, Calv=Ca/Pb. A partition coefficient, in general terms, represents the ratio of chemical concentration in two matrices at equilibrium, and in this case, between blood and air. If Pb is 10, that would imply that the chemical concentration in blood would be 10 times greater than that of the inhaled air at equilibrium. Based on this principle then, Eq. (3.3) can be rewritten to calculate arterial blood concentration Ca, resulting from inhalation exposures as follows:

(3.4)

(3.4)

A close examination of this equation would indicate that, for highly blood-soluble chemicals (i.e., with high Pb), the pulmonary absorption will be influenced by Pb and Qp but not Qc. Given the extensive blood solubility of these chemicals, the delivery rate is essentially the key factor determining Ca, such that an increase in Qp would translate to a corresponding increase in the amount absorbed. Examples of chemicals exhibiting high blood solubility would be 1,4-dioxane (rat Pb=1861) and 2-butoxyethanol (rat Pb=7965).

In the case of chemicals that are poorly soluble in blood (i.e., chemicals with low Pb), the rate of pulmonary absorption is influenced by blood perfusion rate (Qc) and Pb rather than Qp. So, for a given exposure concentration of a chemical with low Pb such as carbon tetrachloride (rat Pb=4.52), the pulmonary absorption is enhanced further only by increases in Qc (facilitating greater systemic entry).

For the oral route, the amount entering the liver following absorption can be calculated as follows:

(3.5)

(3.5)

where Astomach is the amount in the stomach (mg), Ka is the first-order absorption rate constant (h−1), and Rabs is the rate of amount absorbed (mg/h).

In Eq. (3.5), Astomach is initially determined by the dose administered and thereafter by the amount remaining to be absorbed (i.e., nonionized form). In the case of chemicals metabolized by the liver, the fraction of the dose escaping the liver unmetabolized (i.e., fraction that is not subject to metabolism upon entry, also referred to as first pass effect) is accounted for. The use of Ka (h−1) is conceptually similar to the first-order uptake rate described in Eq. (3.1) for dermal pathway. In essence, Ka reflects the proportion of the dose that is absorbed per unit time. For example, if Ka=0.1 h−1, it implies that 10% of the amount in the stomach is absorbed per hour. Thus, after 1 h of oral dosing, an amount equal to 90% will remain unabsorbed; similarly, after the second hour, 10% of the remaining 90% is absorbed (i.e., 9%), leaving 81% of the dose in the stomach/gut, and so on. If the amount absorbed per unit time is constant (e.g., 10 mg/h), regardless of the magnitude of the dose administered (1, 5, 10, or 100 g), then it is said to follow a zero-order process. Dietary exposure to chemicals is sometimes described by a zero-order (or constant) input process, since it results in a fairly constant input dose to the exposed animals. The concepts of proportionality (i.e., first order) and constant input (i.e., zero order) explained here are applicable to all other phases of PK, thereby being critical in interpreting toxicity data.

Distribution

Distribution is the process by which a chemical in systemic circulation moves into the various organs, including metabolizing organs (e.g., liver), excretory organs (e.g., kidney), storage depots (e.g., fat, bone), and target sites (e.g., placenta, brain). Lipid solubility, ionization, and protein binding are key factors determining the extent to which a chemical is distributed in the body.

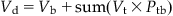

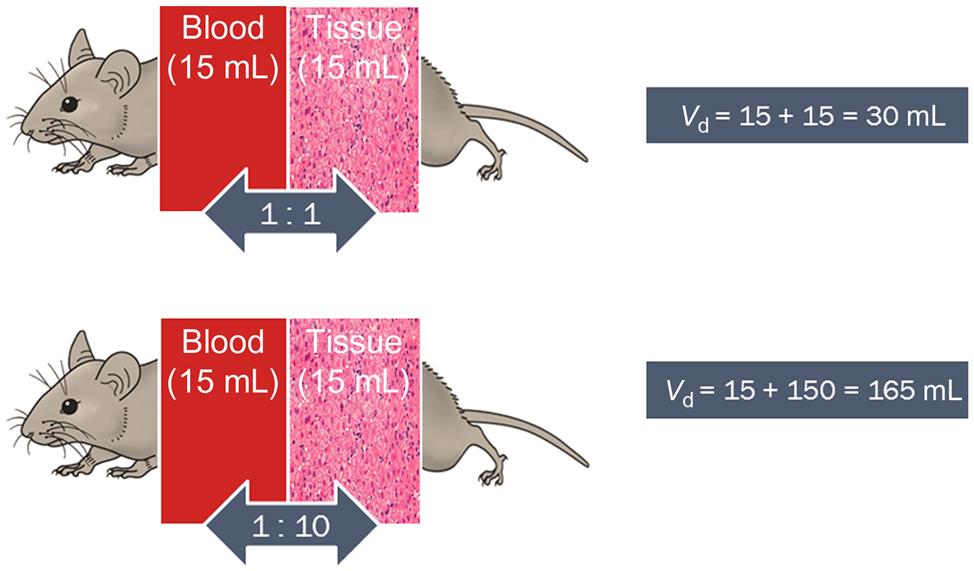

The volume of distribution (Vd) or the apparent volume of blood (or volume of plasma water as reported in the pharmaceutical literature) in which the chemical is distributed or diluted throughout the body determines the resulting chemical concentration. Vd would be equal to the volume of blood if the chemical resided solely and uniformly in the blood components (plasma, erythrocytes). However, Vd would increase as a chemical exhibits greater affinity for binding proteins and lipidic tissues, and thus moves from the plasma water (or blood) into these depots. In this regard, the affinity of a chemical for tissues relative to blood is represented by the tissue:blood partition coefficient (Ptb). The Ptb, with units of mL blood/mL tissue, represents the ratio of the concentration of a chemical in the tissue and blood, at equilibrium. The volume of a tissue (Vt) multiplied by the corresponding Ptb yields the blood-equivalent volume in which the chemical is distributed.

For example, in the case of a chemical with a Ptb of 1, the total Vd is 30 mL if it is distributed in the blood and tissue compartment with volumes of 15 and 15 mL, respectively (Figure 3.4). However, if the Ptb of the chemical is 10, then the physical volumes of tissues and blood remain at 15 and 15 mL, respectively, but the physiological apparent volume of the tissue compartment becomes 150 mL (i.e., Vt×Ptb=15 mL tissue×10 mL blood/mL tissue=150 mL blood; Figure 3.4) to yield a total distribution volume of 165 mL. Accordingly then, the sum of blood volume (Vb) and tissue volumes (expressed as blood-equivalent volume, i.e., Vt×Ptb) is considered to be a reasonable approximation of the Vd of chemicals, as follows:

(3.6)

(3.6)

where Ptp is the tissue:blood partition coefficient, Vd is the volume of distribution (units of volume, e.g., L, mL), Vb is the volume of blood (or plasma), and Vt is the volume of tissue.

Thus, for 1,1,1,2-tetrachloroethane, a chemical with Ptb of 2.1, 51.5, and 0.95 for the liver, fat, and muscle compartments, the computed Vd in the rat would be 1.14 L even though its body weight (i.e., physical volume) is only 0.25 kg. The units of Vd are frequently mL or L, but it is also sometimes reported as volume per kg body weight (mL/kg, L/kg). Empirically, Vd is calculated with knowledge of dose administered (Dose, mg) and the initial blood concentration (C0, mg/L), estimated using PK models (see “Pharmacokinetic (Time-Course) Data and Derivation of Dose Metrics” section), as follows:

(3.7)

(3.7)where C0 is the initial blood concentration (mg/L); Dose is the dose administrated (mg), and Vd is the volume of distribution (unit of volume).

Accordingly, the extensively distributed chemicals (e.g., those that exhibit a marked affinity for fat depots and those that bind to tissue proteins) will have very large Vd, whereas hydrophilic substances exhibit smaller Vd, often close to 0.6 L/kg (approximately equaling the total water content of body, i.e., 60% of the body weight). This water content is the sum total of the content of plasma, intracellular fluid, and interstitial fluid, which correspond to 4%, 35%, and 21% of the body weight, respectively. Depending upon how well or how little the substances distribute within various components of the tissues and blood (i.e., water, lipids, proteins), the apparent Vd differs from chemical to chemical, and from one species to another.

Despite the comparable rate of absorption and Vd of any two chemicals, the resulting blood (or target tissue) concentration and half-life (t1/2) could be different depending upon the extent of the elimination processes, namely metabolism and excretion, as discussed later.

Metabolism

Metabolism or biotransformation in organs such as liver is limited by the delivery (blood flow to the organ) and/or capacity (i.e., of metabolizing enzymes). The enzyme content, the catalytic efficiency of the enzyme, and the binding affinity of the substrate determine the intrinsic metabolic capacity of an organ. The rate of the amount of chemical metabolized per unit time (RAM) is frequently computed on the basis of the maximal velocity (Vmax), affinity for the metabolizing enzyme (Km), and free concentration of the substrate ([S]), as per the Michaelis–Menten equation:

(3.8)

(3.8)where Km is the affinity for the metabolizing enzyme, RAM is the rate of the amount of chemical metabolized per unit time (or rate of metabolism), [S] is the concentration of free substrate, and Vmax is the maximal velocity (mass unit/time unit; e.g., mg/h).

In Eq. (3.8), the ability of the enzyme machinery (in an organ in vivo or in an experimental system in vitro) to remove a substance and thereby clear the exposure (or carrier) medium in which it is present (e.g., blood) is determined by Vmax and Km, or intrinsic clearance (CLint). CLint is expressed in units of volume/time (e.g., L/h) and estimated as follows:

(3.9)

(3.9)

where CLint is the intrinsic clearance (units of volume/time, e.g., L/h).

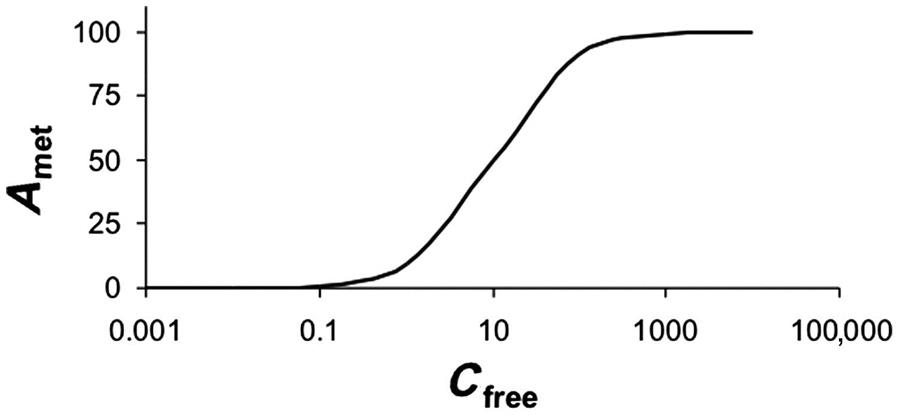

Considering Eqs. (3.8) and (3.9) together, it can be seen that RAM can be calculated as the product of [S] and CLint. Then, as [S] increases (i.e., [S]  Km), the RAM approximates the Vmax, that is, the maximal-metabolizing capacity of the enzyme. On the other hand, at very low substrate concentrations (i.e., [S]

Km), the RAM approximates the Vmax, that is, the maximal-metabolizing capacity of the enzyme. On the other hand, at very low substrate concentrations (i.e., [S]  Km), the RAM is proportional to [S] because CLint is essentially a constant (being approximately equal to Vmax/Km). The values of CLint (calculated as Vmax/Km) vary from chemical to chemical (e.g., CLint of endosulfan=39 L/h, whereas CLint of 1,1,1-trichloroethane=0.02 L/h in rats).

Km), the RAM is proportional to [S] because CLint is essentially a constant (being approximately equal to Vmax/Km). The values of CLint (calculated as Vmax/Km) vary from chemical to chemical (e.g., CLint of endosulfan=39 L/h, whereas CLint of 1,1,1-trichloroethane=0.02 L/h in rats).

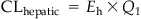

Figure 3.5 illustrates that the RAM for a hypothetical chemical as per Eqs. (3.8) and (3.9) approaches a constant value equal to the Vmax (100 µg/h). So, for this hypothetical chemical, responses seen at high doses (that yield blood concentrations>100 µg/L) should not be extrapolated linearly to predict metabolic rate or response incidence at lower doses. The amount metabolized as calculated per Eqs. (3.8) and (3.9) does not account for physiological limitations, particularly the delivery to the metabolizing tissue in vivo. The latter is determined by the rate of blood flow (Q) to the organ. For example, considering a rate of blood flow to the liver (Ql) in the rat of 1.3 L/h, the implication would be that the rat liver cannot metabolize more than the amount of chemical delivered by 1.3 L blood per hour. This physiological limitation and its relevance to the RAM of a chemical will become evident upon integrating the intrinsic enzyme capacity, CLint, with the Ql, to calculate hepatic clearance (CLhepatic). CLhepatic is defined as the volume of blood (or plasma) from which chemical is removed per unit time and calculated as follows:

(3.10)

(3.10)

where CLhepatic is the hepatic clearance (units of volume/time) and Ql is the rate of blood flow to the liver (units of volume per time).

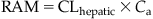

CLhepatic is expressed in units of volume per time (e.g., mL/min, L/h) or sometimes in units of volume per time normalized to the weight of the organ or body (e.g., L/h/kg). Furthermore, the RAM can be estimated from CLhepatic as follows:

(3.11)

(3.11)CLhepatic can also be computed with knowledge of the fraction of chemical in hepatic blood removed by metabolism during its passage (i.e., hepatic extraction ratio) and Ql:

(3.12)

(3.12)where Eh, hepatic extraction ratio [i.e., amount metabolized by liver/amount delivered to liver, fractional difference in arteriovenous concentration of a chemical (Carterial−Cvenous)/Carterial], or ratio of hepatic clearance to hepatic blood flow [i.e., CLhepatic/Ql or CLint/(Ql+CLint)].

The values of CLhepatic and Eh vary among chemicals. For example, in the rat, Eh=0.02 for 1,1,1-trichloroethane and Eh=0.92–0.97 for endosulfan and trichloroethylene. A high Eh value (≥0.7) would suggest that the chemical is highly cleared by the liver, implying that Ql rather than the enzyme content is the limiting factor of metabolic clearance. The metabolic clearance of a chemical exhibiting a small Eh value (<0.1) would be limited by the enzyme capacity and not delivery, that is, even if more chemical enters the liver, the metabolism will only occur at a low rate characterized by its CLint. The concepts of nonlinearity and physiological limitation discussed earlier are also applicable to other elimination processes, including urinary excretion (vide infra).

Excretion

The elimination of a chemical from the systemic circulation of a treated animal depends not only upon metabolic clearance but also upon other excretion processes. These include exhalation, urinary excretion, biliary and fecal excretion, and transfer via milk, hair, saliva, etc.

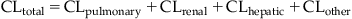

The total clearance (CLtotal) of a chemical from systemic circulation then equals the sum of all individual clearance (elimination) processes occurring in parallel. Accordingly,

(3.13)

(3.13)where CLtotal is the total clearance, CLpulmonary is the pulmonary clearance, CLrenal is the renal clearance, CLhepatic is the hepatic clearance, and CLother is the elimination from other potential metabolism organs.

In the “Metabolism” section, Eq. (3.10) was presented and described for its use in calculating CLhepatic. Similar calculations of the number of liters of blood cleared of a substance per unit time can also be performed for other elimination processes. Thus, the pulmonary clearance is calculated as Qp/Pb. Accordingly, chemicals with low Pb show high CLpulmonary (e.g., cyclohexane with Pb=1.4 and CLpulmonary=3.2 L/h, in the rat), whereas the reverse is true for VOCs with high Pb values (e.g., 2-butoxyethanol with Pb=7965 and CLpulmonary=0.0007 L/h).

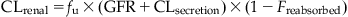

In the case of urinary excretion, glomerular filtration, tubular reabsorption, and tubular secretion together determine the overall rate and amount of chemical excreted. Accordingly then, CLrenal is equal to the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) if there is no tubular reabsorption or secretion. However, when these processes are not negligible, CLrenal is calculated as follows:

(3.14)

(3.14)

where CLsecretion is the clearance by tubular secretion, Freabsorbed is the fraction reabsorbed, fu is the unbound fraction of the chemical in systemic circulation, and GFR is the glomerular filtration rate.

The competing and net influence of ADME processes results in a certain time-course profile (e.g., AUC0–t) of the chemical concentration in the target organ of experimental animals. The exposure of the target organ to the chemical and its metabolites can be assessed, where feasible, by measuring them in selected biological matrices. Such derivations of dose metrics from PK data and their usefulness relative to the administered dose are discussed in the following section.

Pharmacokinetic (Time-Course) Data and Derivation of Dose Metrics

The tissue responses observed in toxicity studies is a result of the toxic form of the chemical (parent or metabolite) being delivered in some quantity over a specific duration (t) to the target organ. For systemically acting chemicals (which induce toxicity in organs other than the portals of entry), the measure of dose to the target is critical not only for interpreting the toxicity data but also for extrapolating to other test or exposure systems (e.g., route, scenario, dose, exposure matrix, species). In this regard, the administered dose or daily intake (mg/kg/d) was used in the past because it was the most readily available measure of dose and for which measurement methods (development and implementation) were least tedious. Even though this dose measure accounts for body weight differences between animals, it does not take into account any qualitative or quantitative differences in PK processes across doses, routes, and species (on the basis of toxic moiety of chemicals). Therefore it is the least relevant measure of dose to the target tissue.

The next level of refinement in terms of the dose measure for analyzing responses in a toxicology study would involve the use of absorbed dose, which accounts for differences in body weight as well as species-specific differences in absorption efficiency and bioavailability. While this dose measure is more closely related to the tissue response than administered dose, it does not account for the potential dose-, route-, time-, and/or species-specific differences in unbound concentration in plasma or distribution to target tissues. Furthermore, such a dose measure does not explicitly account for the rate or extent of formation of active metabolite(s). Therefore, the maximal, average, or integrated concentration of the chemical or its metabolite(s) in blood (or plasma water) is increasingly used for monitoring internal exposure, and for extrapolating/interpreting toxicity data.

This approach reflects the basic tenet of PK that the unbound or active form of the chemical in blood is a key determinant of tissue responses. Blood (or plasma), besides being a convenient sampling site, represents a reasonable reference biological fluid for kinetic calculations as it reflects the net impact of bioavailability, uptake, distribution, and elimination processes in the organism. Since the tissues equilibrate with blood (i.e., as reflected by the Ptb), it further effectively reflects the extent of target exposure.

Two common measures of dose metric based on blood are: Cmax and AUC0–t. Whereas Cmax represents the maximal concentration (or the peak concentration) in a time-course curve, AUC0–t is the integral measure of internal exposure over a given period of time. When the parent chemical is the toxic moiety, Cmax correlates well with acute responses (e.g., neurotoxicity of toluene), whereas AUC0–t is the better internal dose metric for chronic effects (e.g., cancer). The selection of appropriate dose metrics is critical to a sound interpretation and extrapolation of toxicological data collected under one set of exposure conditions.

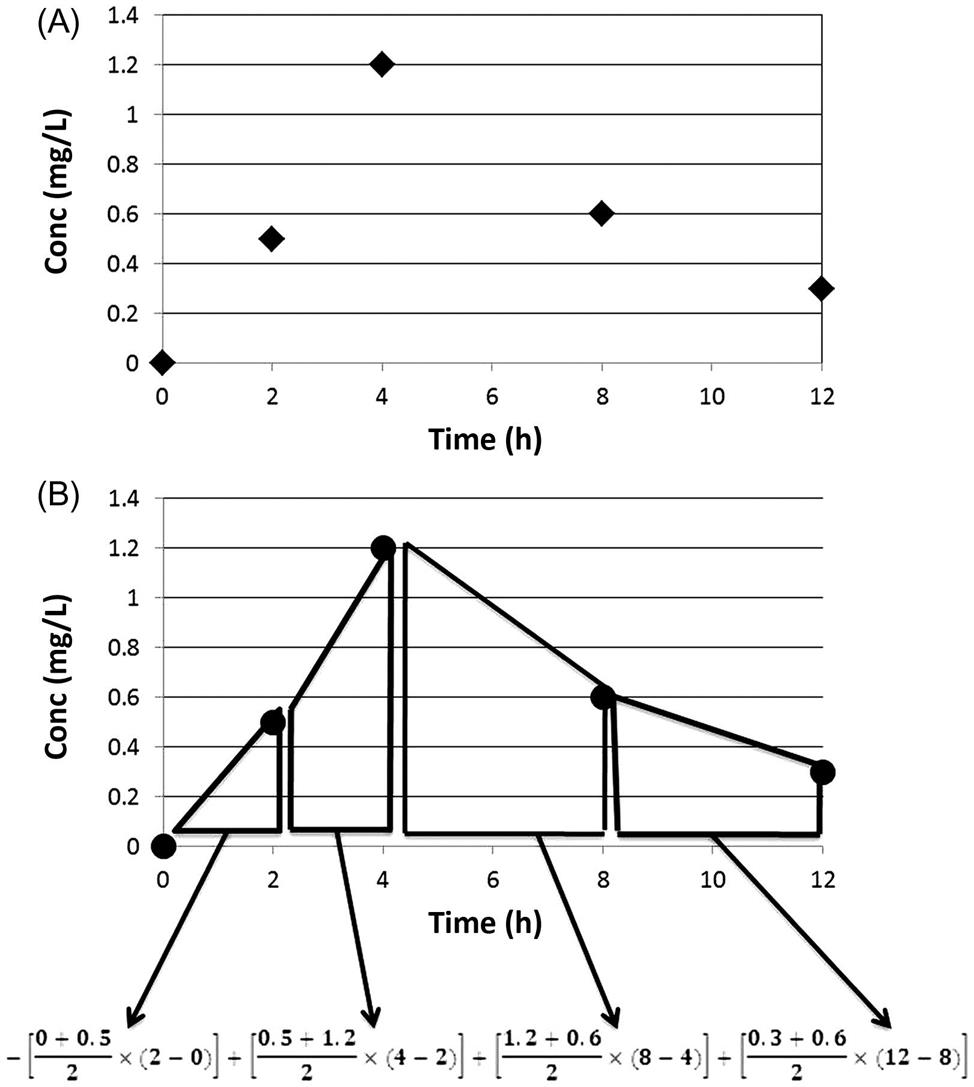

Let us consider the measurements of 0, 0.5, 1.2, 0.6, and 0.3 mg/L of a substance at 0, 2, 4, 8, and 12 h postadministration (Figure 3.6). In this case, based on the measurements made in the exposed animal, the Cmax is 1.2 mg/L. The AUC0–t is calculated by integrating the concentrations over the duration of interest. As shown in Figure 3.6, determining the area under each trapezoid and then adding them together can compute AUC0–t. This is done by: (1) taking the average concentration during two consecutive sampling times and (2) multiplying it with the corresponding time interval. Thus, the AUC of the first trapezoid would be: [(0+0.5)/2]×(2−0), or 0.5 mg/L×h. The AUC for the subsequent trapezoids are: 1.7, 3.6, and 1.8 mg/L×h, respectively. The total AUC then corresponds to 7.6 mg/L×h (=0.5+1.7+3.6+1.8). This AUC, for example, can be used as a basis for comparing responses across dose groups, studies, or even species. With knowledge of elimination constant, the AUC for extended periods of time can be calculated.

In order to obtain reliable estimates of Cmax and AUC0–t, appropriate design of TK studies is essential. Collection of PK data in the main study groups or a satellite group can be done in these studies. However, the sampling times should permit the characterization of Cmax; also, sufficient blood samples should be collected during critical phases to calculate AUC0–t. But care should be taken not to take more than 10% of the total blood volume from the small laboratory animals, in a given week.

At least five, and preferably seven, time points are used to characterize the entire time-course of the kinetics of a chemical. Of these, at least two time points should be in the early (absorption/distribution) phase and at least three time points in the terminal elimination phase. In case of an oral-dosing study, at least one sample should be obtained before the tmax to facilitate reliable characterization of the TK profile of a substance, including the absorption phase. In terms of the sampling during elimination phase, the time interval between the first and last sampling time points should at least be twice the t1/2 of the substance. For the estimation of AUC0–t, sampling during at least three t1/2 beyond tmax is considered reliable. Specialized designs and statistical analyses can be employed to strike a balance between sampling time intervals and minimization of the number of samples while focusing to get a reasonable estimate of the dose metrics.

Since the collection of all desired data on blood or tissue concentrations as a function of time, dose, duration, and species is not routinely possible, mathematical tools are used to construct the required time-course curves. These tools, referred to as PK models, are quantitative descriptions based on either empirical modeling of PK data or mechanistic understanding of the critical determinants of the ADME processes, as described below.

Pharmacokinetic Models and Computation of Dose Metrics

When the dose metrics of interest (e.g., AUC0–t, Cmax) cannot be measured at all desired time points and matrices in the treated animals, they can be computed using PK models based on available data or parameters. These PK models range from a simple, one-compartmental model to complex multicompartmental models.

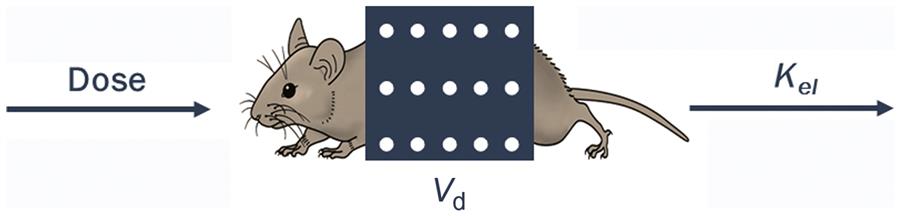

One-Compartment Model

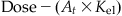

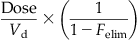

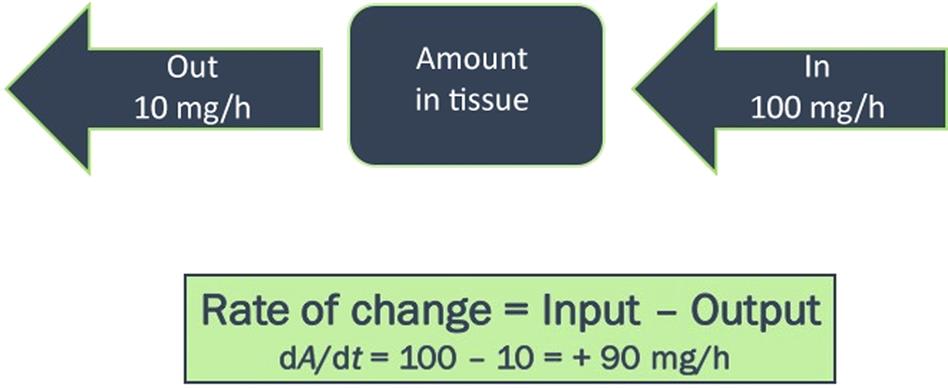

The one-compartment PK model considers the body as a single homogeneous compartment (Figure 3.7). This model is based on the assumption that the absorbed chemical is distributed uniformly in all tissues and at all times. In the simplest case illustrated here, the amount of a chemical in the body results from the input rate corresponding to the administered dose (mg/h) minus the output (or elimination, mg/h). The chemical concentration in tissues and blood can then be determined by dividing the amount in body by the volume in which the chemical is distributed (Vd). The basic equations underlying the one compartment model are listed in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1

Summary of Equations Associated With, and Derived From, the Simplest One-Compartmental PK Model. Dose indicates absorbed oral dose.

| Output | Model equation |

| Rate of change in the amount of chemical (dAt/dt, mg/h) |  |

| Amount or body burden at specific time t (At) |  |

| Concentration in blood or tissue at specific time t (Ct) |  |

| Half-life (t1/2; h or min) |  |

| Clearance (Cl; L/h or L/min) |  |

| Amount or body burden (A) |  |

| Concentration in blood at steady-state (Css) |  |

| Area under the blood concentration vs time curve (AUC; mg/Lxh) |  |

| Fraction eliminated (Felim) |  |

( ) ) |  |

( ) ) |  |

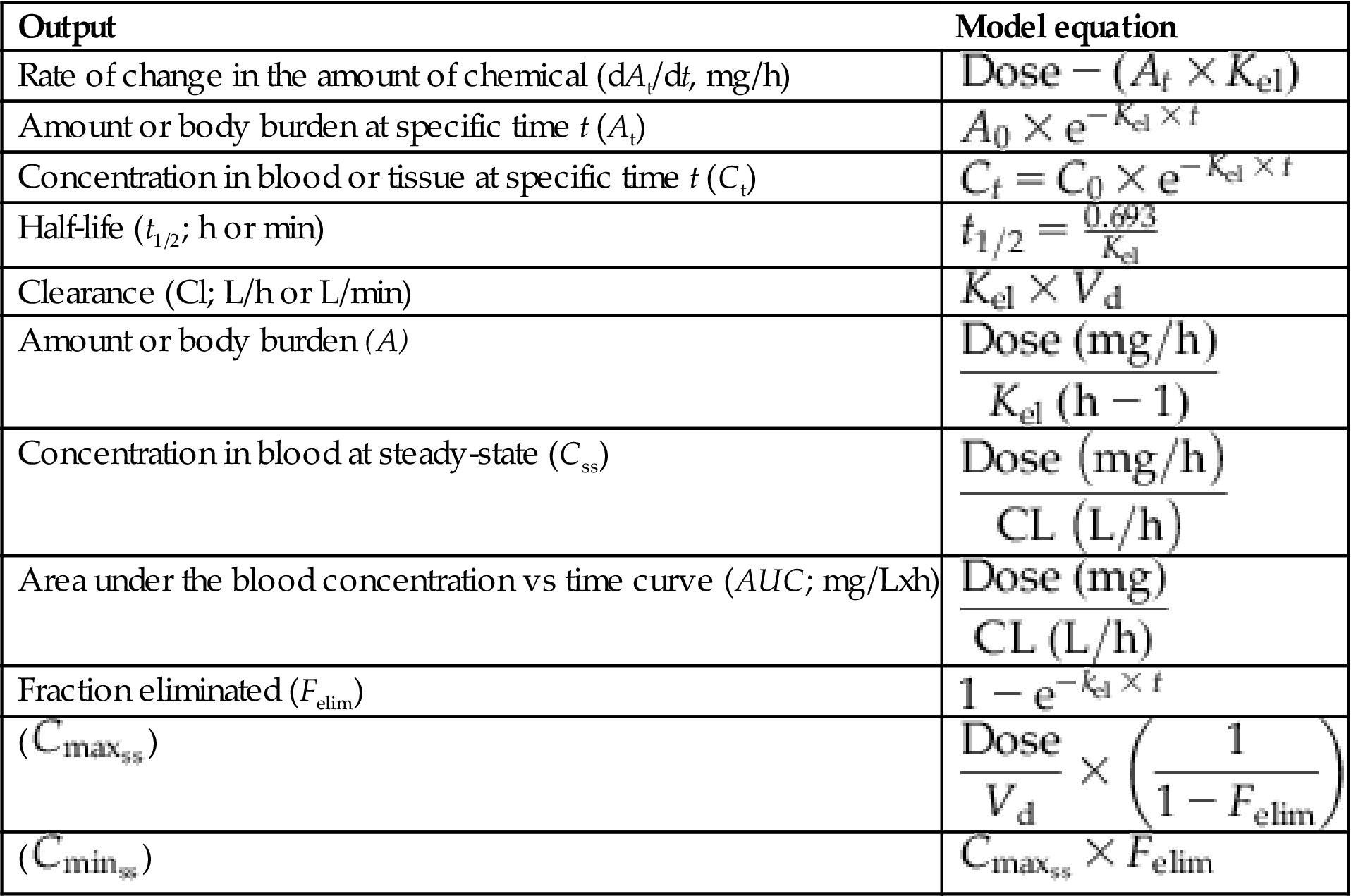

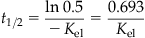

Figure 3.8A presents a plot of the plasma concentration data collected for a hypothetical chemical at various time intervals following a single iv dose. The measured concentrations were 1.2, 0.6, 0.3, and 0.15 mg/L at 2, 4, 6, and 8 h postdosing. Therefore, the initial concentration, namely C0, is not known and needs to be estimated by extrapolation. In order to do that, and to estimate the eliminate rate constant (Kel), logarithmic transformation of the data is applied (Figure 3.8B). The intercept (ln C0=0.8755; or upon linear transformation equals 2.4 mg/L) equals the initial plasma concentration, whereas the slope (=0.437 h−1) corresponds to the Kel. The elimination or terminal half-life (t1/2, in units of minutes, hours, weeks, months, years, etc.), defined as the time taken for the concentration (or body burden) to decline by 50% of the initial value, is obtained from Kel as shown in the following equation:

(3.15)

(3.15)

where Kel is the elimination rate constant and t1/2 is the elimination or terminal half-life (units of minutes, hours, weeks, months, years).

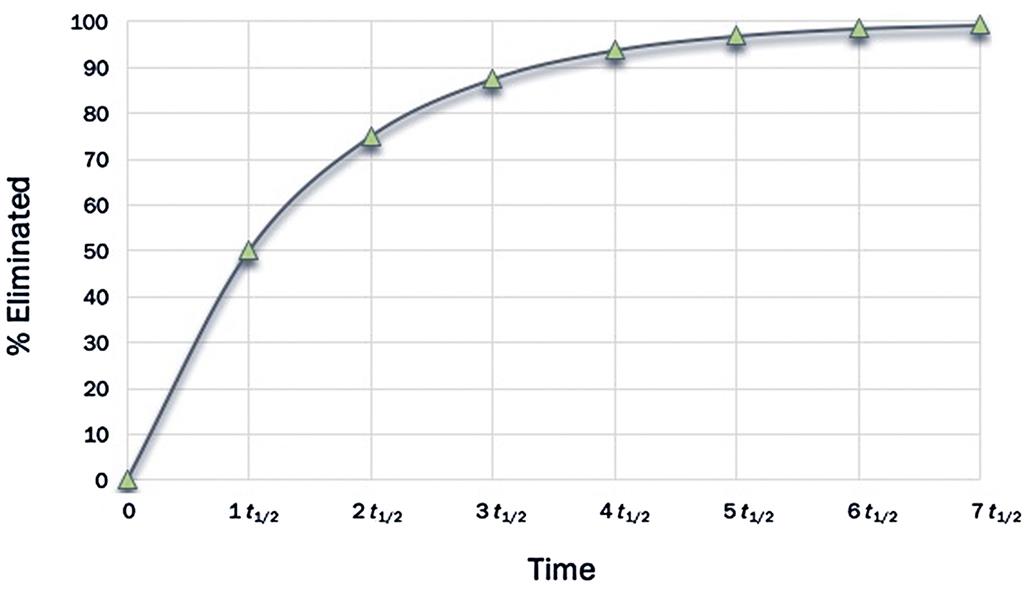

Accordingly, after one t1/2, the initial concentration would have come down by 50%. After the second t1/2, half of the remaining quantity (i.e., 50% ÷ 2 = 25%) is eliminated such that the total elimination amounts to 75%. After the third t1/2, half of the remaining amount (i.e., 12.5%) is eliminated such that the total eliminated at the end of the third t1/2 is 87.5% of the initial quantity. Continuing this calculation would indicate that after 4, 5, 6, and 7 t1/2, a total of 93.7%, 96.9%, 98.5%, and 99.25% would be eliminated, respectively. Figure 3.9 is a pictorial representation of the percent dose eliminated as a function of t1/2. From this figure, one can formulate that, at about five t1/2, the substance in the body is nearly fully eliminated.

Even though the Kel value for a given chemical can be estimated by modeling the time-course data in a biological matrix taken from treated animals, attention should be given to planning the data collection. For example, estimating Kel from just two Ct values obtained from the elimination phase might be unreliable due to inadequate consideration of within-animal and between-animal variability, as well as uncertainty in estimates. Therefore, when estimating Kel or t1/2, the time interval between the two measured concentrations should be equal to at least one t1/2, and it is preferable to collect such data during time spanning at least three to four t1/2.

The compartmental PK model described earlier and associated parameters (Table 3.1) are “data-driven,” and require that the time-course data on chemical (or its metabolite(s)) concentration be collected in a biological matrix (blood, plasma, tissue, urine, or exhaled air) for each dosing regimen in each species. An alternative to such an intensively data-based approach is physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling, described in the next section.

Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Models

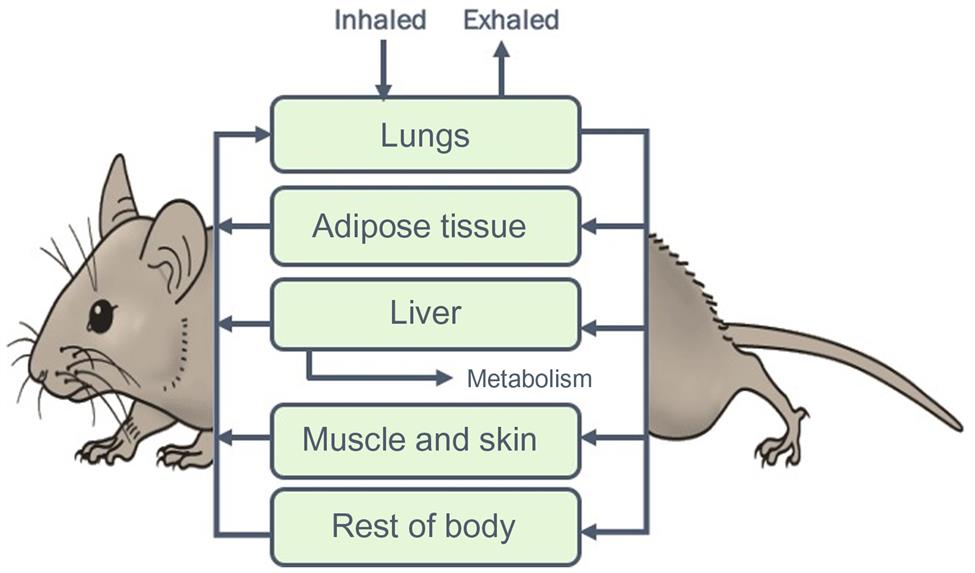

The PBPK models are quantitative descriptions of the interrelationship among the determinants of ADME, based on the concepts of clearance and volume of distribution, discussed earlier. The initial step in the construction of PBPK models involves development of a conceptual representation—the complexity of which is consistent with the goals and intended end-use of the model. In this process the organism is represented as a network of compartments, each of which is physically, physiologically, and biochemically characterized. The exposure and elimination routes are indicated by adding arrows to the appropriate compartments (Figure 3.10). Each compartment may represent a single tissue or a group of tissues with similar kinetic characteristics. For example, tissues with poor or slow blood perfusion characteristics (such as the muscle and skin) are frequently grouped within a compartment referred to as “slowly perfused tissues.” Since the skeletal and structural components of the body have negligible perfusion and are not key determinants of the kinetics of many organic chemicals, they have not been routinely included in the PBPK models for this subset of chemicals. However, while modeling the kinetics of certain metals and metalloids, a detailed characterization of the bone/skeletal compartments is included.

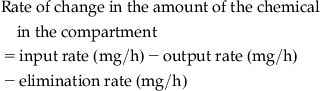

Each compartment in a PBPK model is described using a mass-balance differential equation of the following form:

(3.16)

(3.16)Considering the “internal” tissues described in the model, the chemical input is via the arterial blood whereas the output occurs via the venous blood flow. The rate of change in the amount of chemical in a nonmetabolizing tissue then equals the arterial–venous difference (Figure 3.11).

The free concentration of chemical leaving the tissue is computed with the knowledge of the tissue concentration (i.e., amount/tissue volume) and tissue:blood partition coefficient. The greater the partitioning into a tissue or the rate of metabolism in a tissue, the less would be the amount of chemical leaving that tissue. The simplest form of PBPK models then are based on compartment-specific input parameters that correspond to the tissue volumes, tissue blood flow rates, partition coefficients, and metabolism rates. These parameters as well as corresponding mass-balance equations are integrated and solved using commercially available software or freeware to simulate the kinetic behavior of a chemical in the test animal species.

The generic input parameters of PBPK models are physiological, biochemical, or physicochemical in nature. The key physiological parameters include alveolar ventilation rate, cardiac output, tissue volumes and tissue perfusion rates, and GFR. Some or all of these parameters can be measured in the experimental animals or obtained from biomedical literature. The physicochemical parameters required for PBPK models refer primarily to the blood:air and tissue:blood partition coefficients, which together with the volumes of tissues and blood facilitate the calculation of the Vd. Unlike the classical compartmental PK models, the Vd specific to each tissue is calculated in PBPK models with the use of tissue:blood or tissue:plasma partition coefficients. Several in vitro, in vivo, and in silico (algorithm) methods are available for estimating the partition coefficients of chemicals required for PBPK modeling. The biochemical parameters required for PBPK modeling, such as the rates of absorption, biotransformation, macromolecular binding, and excretion, have been determined either by conducting time-course analysis in vivo or upon extrapolation of data collected in vitro.

A critical aspect in PBPK modeling relates to the evaluation and selection of models that are fit for the purpose. It is important to select a PBPK model that can adequately address a particular issue at hand (e.g., route-to-route extrapolation, high dose to low dose extrapolation, species to species extrapolation). This process, in the context of PBPK model use for animal toxicity testing, would require the consideration of the following aspects:

1. The species for which the PBPK model has been constructed versus the species used in the toxicity study requiring interpretation.

2. The developmental stage(s) for which the PBPK model has been parameterized and evaluated versus the life-stage for which the model is intended to be used for interpreting/designing a toxicity study.

3. The exposure route used in the toxicity tests versus exposure route(s) described in the model.

4. The exposure duration and maximal dose for which the model has been tested versus the exposure protocol of the proposed toxicity study.

The compartmental models including the PBPK models are useful in the estimation of blood and tissue concentrations associated with a single dose or repeated doses given by various routes, and this can frequently be accomplished using a single set of parameters. In other instances, reestimation or adjustment of parameter values might be necessary to accommodate the observed or anticipated change in input parameters with time (e.g., change in Vd due to body fat content, change in CLint due to enzyme induction). Even though temporal changes in dose metrics can be effectively modeled with these kinetic models, often in reality the rate of change in the blood concentration approaches zero during repeated (or lifetime) exposures. This situation is termed as steady-state, that is, the numerical value of a variable remains constant during a given interval of time. The “steady-state” should not be confused with “equilibrium,” which implies the cancellation of driving forces on either side. At steady-state, the input (dose rate) equals elimination rate such that the observed internal concentration is a constant value or range. The steady-state situation then requires fewer parameters than the full-fledged kinetic models (Table 3.1).

Pharmacokinetics and Its Use in Designing Toxicity Studies

Animal toxicity studies use various dosing regimens and protocols ranging from a single-dose (acute) study to lifetime (chronic) exposure studies. It is critical to take into account the PK characteristics of the chemical in selecting doses, dosing regimens, and sampling times. In this regard the available ADME data or PK models can be used to evaluate the following aspects/questions:

1. What is the rate of absorption for the dose levels, route, and vehicle chosen for the study, i.e., what fraction is absorbed during a given time frame?

2. What are the blood:air and skin:air partition coefficients of the chemical?

3. What percentage of the chemical remains in the nonionized form at physiological pH?

4. Are there significant bioavailability issues for the route and vehicle of exposure used in the experiment? If so what is the most critical factor influencing it?

1. What is the volume of distribution (or tissue:blood partition coefficient) of the test chemical?

2. How does the volume of distribution compare to the body weight of the animal?

3. Are there specific binding/transport phenomena demonstrated or suspected for this chemical?

4. Does the extent of binding/transport appear to vary as a function of dose or species?

5. Is the distribution limited by membrane diffusion or blood flow to tissues?

1. What are the key pathways and enzymes involved in the metabolism of the chemical?

2. Are there quantitative estimates of metabolism parameters for the chemical (Vmax, Km, or CLint) as a function of species, life-stage, and duration of exposure?

3. What dose level corresponds to the deflection point of the linear kinetics in the test species of interest?

4. How does the CLint of the chemical compare with the hepatic blood flow?

5. What is the significance of extrahepatic metabolism pathways and rates?

1. What are the major excretion pathways in the test species of interest?

2. Are the rates known for each of the major excretion pathways?

3. If so, how do they compare with the physiological limits for organ clearance (i.e., blood flow rates)?

An understanding of these aspects is key to the interpretation of the kinetic behavior of a chemical in terms of the critical dose metrics across dose, routes, and species. In this regard, the above ADME factors can be integrated within a PK model to facilitate predictions of their impact on a given dose metric, under various hypothetical dosing scenarios. Thus, the quantitative use of PK data/model can help select the spacing and number of doses. Such PK information is also critical in planning future/supplementary studies by a different route or in a different species. In this regard, PBPK models or steady-state algorithms can be used to compute the pharmacokinetically equivalent dose for one route of exposure from another (e.g., inhalation to oral).

The PK data and models are also useful in choosing dose levels that will remain in the linear range, and in selection of appropriate sampling times during which the concentrations of parent chemical and/or metabolite(s) are likely to remain well above the limit of quantitation of the analytical method. In this regard, predictive models, such as PBPK models, are uniquely useful in providing a priori simulation of concentration versus time-course data, based on independent estimates of parameters using in vitro or in silico approaches. This particular application facilitates the selection of blood or tissue sampling times corresponding to critical phases of the PK curve so that reliable calculations of AUC0–t can be made, avoiding the assignment of unequal weighting to selected portions of the PK curve.

Concluding Remarks

PK data and models are essential for effective design and interpretation of toxicity studies. Dose metrics of relevance to the mode of action of chemicals (e.g., Cmax, AUC0–t) are more effective than the administered dose, in relating to the response seen in systemic toxicity studies and cancer bioassays. The PK data collected in test animals or in satellite groups should be analyzed to develop parameters and/or models, given the intended end-use. In this regard, PBPK models are powerful tools for integrating the determinants of absorption, metabolism, protein binding, etc., obtained in vitro with animal physiology for providing simulations of outcome in intact animals. The integration of PBPK models with biologically based pharmacodynamic models would enhance the potential of simulating the time-course of the relevant dose metrics and toxicological responses in exposed animals and humans based on kinetic and dynamic mechanisms.