The Integumentary System

Kelly L. Diegel1, Dimitry M. Danilenko2 and Zbigniew W. Wojcinski3, 1GlaxoSmithKline Research & Development, King of Prussia, PA, United States, 2Genentech, South San Francisco, CA, United States, 3Drug Development Preclinical Services, LLC, Ann Arbor, MI, United States

Abstract

The integument is one of the most dynamic and important of organs. Having a unique role as a first line defense against numerous environmental insults (e.g., physical trauma, temperature fluctuations, infectious and chemical agents, ultraviolet radiation), the health of the skin impacts and reflects the health of the organism. In toxicologic pathology the skin may represent a target organ for those compounds that make direct contact with it, but it also may reflect changes in other internal organs (e.g., jaundice), serving as an external reflection of various internal pathophysiologic conditions. This chapter reviews the most important aspects of the skin as a toxicologically relevant organ.

Keywords

Dermatotoxicology; dermatopathology; skin structure; skin function; skin toxicology; comparative cutaneous toxicology; epidermis; dermis; cutaneous adnexa; keratinocytes; cytokines; cutaneous irritation; skin irritation; skin injury; skin pathology; cutaneous immunology; cutaneous immunopathology; cutaneous carcinogenesis; skin carcinogenesis; phototoxicity

Introduction

The integument is one of the most dynamic and important of organs. Having a unique role as a first line defense against numerous environmental insults [e.g., physical trauma, temperature fluctuations, infectious and chemical agents, ultraviolet (UV) radiation], the health of the skin impacts and reflects the health of the organism. Beyond barrier function, the skin is also important as a neurosensory organ, acts as an endocrine organ, is an essential component of the immune system, aids in locomotion, and has essential psychologic/behavioral functions in many species. In toxicologic pathology, the skin may represent a target organ for those compounds that make direct contact with it, but it also may reflect changes in other internal organs (e.g., jaundice), serving as an external reflection of various internal pathophysiologic conditions.

Structure and Function

The structure of the integument of any given species is as unique as the species itself, reflecting the adaptive nature of an organ that very much reflects and reacts to the environment to which it is exposed. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to give details of the integument for all creatures furred, feathered, haired, horned, scaled, or spined. The following review focuses instead on the essential elements of the skin common to animal models used in toxicity studies and humans: the epidermis, dermis, subcutis, and adnexa.

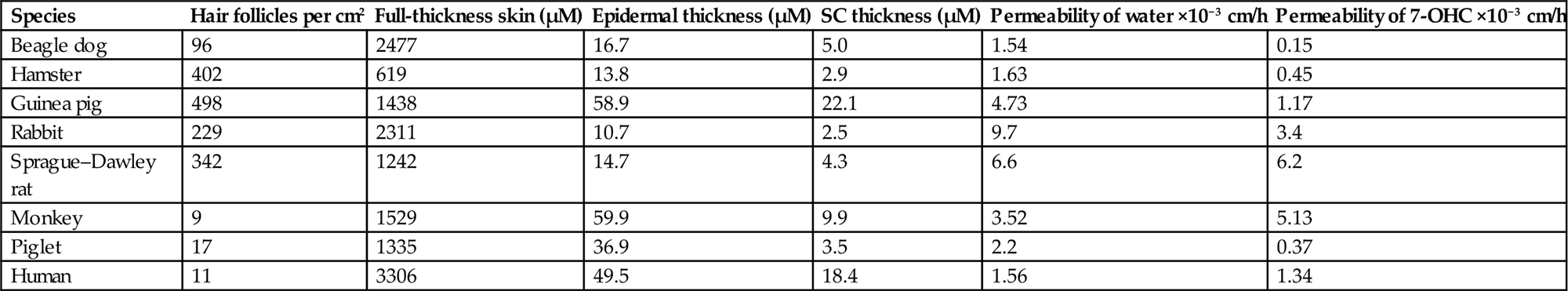

Although there are aspects of the morphology of the integument that are unique to a given species, there are several generalizations that hold true in comparative dermatology. In general, the thicker the hair coat, the thinner the skin. Since hair is in part protective, the need for a thick epidermis in furred animals is not as great as it is in sparsely haired animals like pigs and humans. The latter tend to have compensatory thick epidermal layers for additional protection in the absence of thick fur. The hair follicle density of the rat is more than 30 times that of the human, while the epidermis of the rat is less than ¼ the thickness of human epidermis. It also follows that a thicker epidermis needs a thicker dermis for support. As epidermal thickness increases, so too increases the dermal contribution to overall skin thickness (Table 24.1).

Table 24.1

Comparison of Features of Skin From Major Laboratory Animal Species and the Human

| Species | Hair follicles per cm2 | Full-thickness skin (µM) | Epidermal thickness (µM) | SC thickness (µM) | Permeability of water ×10−3 cm/h | Permeability of 7-OHC ×10−3 cm/h |

| Beagle dog | 96 | 2477 | 16.7 | 5.0 | 1.54 | 0.15 |

| Hamster | 402 | 619 | 13.8 | 2.9 | 1.63 | 0.45 |

| Guinea pig | 498 | 1438 | 58.9 | 22.1 | 4.73 | 1.17 |

| Rabbit | 229 | 2311 | 10.7 | 2.5 | 9.7 | 3.4 |

| Sprague–Dawley rat | 342 | 1242 | 14.7 | 4.3 | 6.6 | 6.2 |

| Monkey | 9 | 1529 | 59.9 | 9.9 | 3.52 | 5.13 |

| Piglet | 17 | 1335 | 36.9 | 3.5 | 2.2 | 0.37 |

| Human | 11 | 3306 | 49.5 | 18.4 | 1.56 | 1.34 |

From Haschek, W.M., Rousseaux, C.G., Wallig, M.A. (Eds.), 2013. Haschek and Rousseaux’s Handbook of Toxicologic Pathology, third ed. Academic Press (Elsevier), San Diego, CA, Table 55.1, p. 2220, with permission.

Another generality is that the thicker the epidermis, the more vascular the upper (papillary) dermis. Essentially, increased vasculature becomes necessary to provide nutrients and flush waste products from thicker overlying avascular epidermal layers. Human skin is a good example, having a rich superficial vascular plexus in the papillary dermis. Of course, having a rich vascular network present superficially also leads to an increased potential for systemic exposure to any material, xenobiotic or other, that can cross through the epidermis into the dermis. A thin epidermis may also increase the risk of systemic exposure to exogenous substances on the skin. However, the thicker hair coat and less vascularized dermis of species with thinner epidermal layers are as such somewhat protective against absorption of chemicals through the skin.

The Epidermis

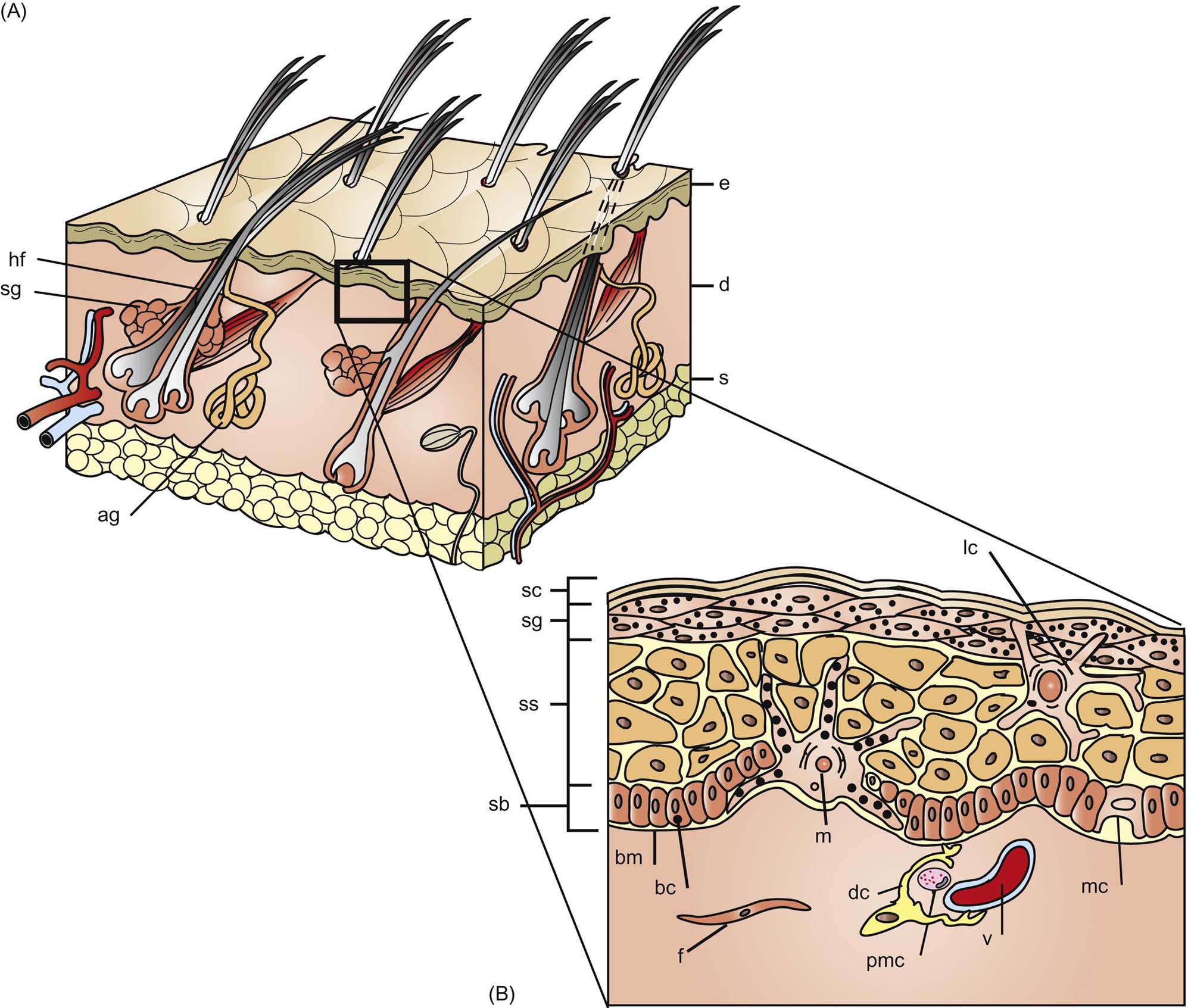

The epidermis is the outermost layer of the skin, providing the majority of protective barrier function to the body. Morphologically, it is divided into layers named for positional and microscopic/submicroscopic features of cells in each layer: the stratum basale (SB), stratum spinosum (SS), stratum granulosum (SG), stratum lucidum (SL), and stratum corneum (SC) (Figure 24.1).

Desmosomes adjoining neighboring cells of the SS give rise to artifactual spine-like formations between cells in fixed tissues giving the layer its name. In the SS, synthesis of a number of proteins important to the differentiating keratinocyte begins, including involucrin, profilaggrin, and filaggrin.

Also in the SG, and in the most superficial part of the SS, are lamellar bodies, organelles best classified as secretory lysosomes that contain a number of important substances: lipids that are released to form the lipid portion of the intercellular “mortar” of the corneocyte “bricks” of the SC; hydrolytic enzymes including acid proteases that aid in the process of desquamation; and proteins, for example, defensins, that contribute to barrier defense against pathogens. As the contents of the lamellar bodies are extruded and the nucleus and organelles of the keratinocyte are lost, the corneocyte is formed.

The intricate process of cornification requires complex cell–cell communication and adhesion. The cytoskeleton of the epidermal keratinocyte has complex networks of proteins that include microtubules, actin filaments, and intermediate filaments (i.e., keratin). Synthesis of keratin in any of its forms is an almost exclusive characteristic of epithelial cells.

Desmosomes are formed largely from desmogleins and desmocollins and represent the primary means of cell–cell adhesion in nucleated epidermal layers. Tight junctions form between neighboring keratinocytes to regulate molecular movement between cells and maintain basolateral cell positioning. Adherens junctions contribute to cell motility and shape via links to internal cytoskeletal components such as actin. Important components of these structures in the keratinocyte include the transmembrane link, E-cadherin, and the intracellular actin-binding α-catenin. Gap junctions are formed from aggregation of connexins into connexons that join adjacent cells to allow intercellular transport of ions and other small molecules.

The keratinocyte life cycle as described earlier ranges from 5 to 30 days, depending on the anatomic site and state of health of the skin. A few specialized cell types present in the skin deserve special mention with respect to function of the skin as an organ.

Melanocytes

The melanocyte provides pigmentation to the skin or fur necessary for behavioral aspects of survival such as camouflage in certain species. Furred species typically have reduced or absent epidermal melanogenesis (the process of melanin production), instead relying on the hair coat for pigmentation and UV absorption. Sparsely haired species like humans rely on largely on epidermal melanogenesis for protection from UV damage to the skin. In addition to their presence in the epidermis, melanocytes are also found in the eye, cochlea of the ear, the brain/meninges, and the heart. Melanin in melanocytes provides a means by which the skin can defend against the potential genotoxic effects of harmful UV radiation (UVR). Melanin can also bind certain potentially harmful compounds such as cations and metals.

Melanocytes are actively phagocytic, dendritic cells (DCs) derived from the neural crest, and generate pigment in membrane-bound melanosomes. Each melanocyte “serves” about 30–40 keratinocytes in the basal layers of the epidermis. Melanosomes are organelles derived from the endoplasmic reticulum of melanocytes and serve as packages for transfer of melanin. Although the number of melanocytes remains constant, the production and transfer of melanosomes to keratinocytes can be up- or downregulated. Melanosomes form a cap overlying the nucleus of the recipient keratinocyte, protecting the nuclear DNA from harmful UVR.

Merkel Cells

Arranged along the base of the epidermis and outer hair follicle, Merkel cells are DCs thought to be of epidermal stem cell origin. They represent a cell type unique to the skin and oral mucosa, capable of acting as mechanoreceptors with dense granules containing neurotransmitter-like mediators. They also contain cytokeratins, providing evidence for an epithelial origin. These cells form complexes with somatosensory nerve fibers. The dendrites of the Merkel cells contact unmyelinated axons in the epidermis, where they function together as a unit (tylotrich pads) to signal adnexal secretions (sweat), changes in blood flow, tactile sensation, and possibly serve in a paracrine function along with other cells of the skin.

Langerhans Cells and Dermal Dendritic Cells

Langerhans cells (LCs) and dermal dendritic cells (DDCs) are bone marrow monocyte-lineage–derived cells that are key components of adaptive and innate immune defense in the epidermis and dermis, respectively. LCs are the primary epidermal DC populations, and are spaced regularly throughout the suprabasilar epidermal layers, adherent to keratinocytes through desmosomal and tight junction attachments. They represent 1%–3% of total epidermal cell count, varying dependent upon anatomic location. In healthy skin, these cells are relatively inactive and even act to attenuate inflammatory response. They are able to preferentially respond to specific or severe foreign antigens, thereby preventing continual upregulation of inflammatory mediators whenever foreign antigens are sensed, which is nearly constant in the skin.

LCs interact with other DC populations in the skin, some of which are still being characterized. DDCs are also important in cutaneous innate and adaptive immunity. The combined efforts of LCs and DDCs in the skin result in immune defense responses unique to the skin; more detailed information on the role of LCs, DDCs, and other cutaneous DC populations in cutaneous immunity and response to injury is presented in the “Response to Injury” section.

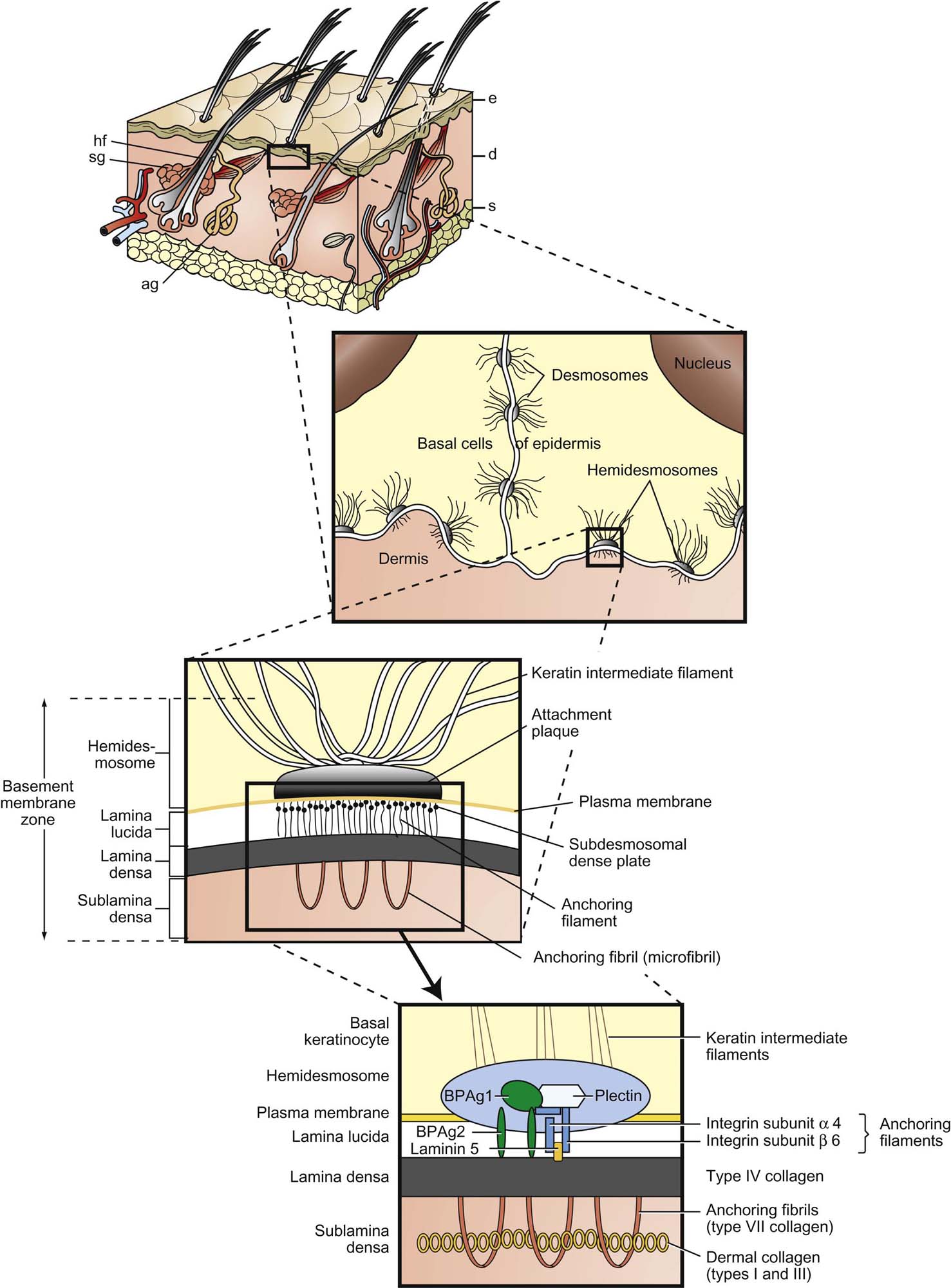

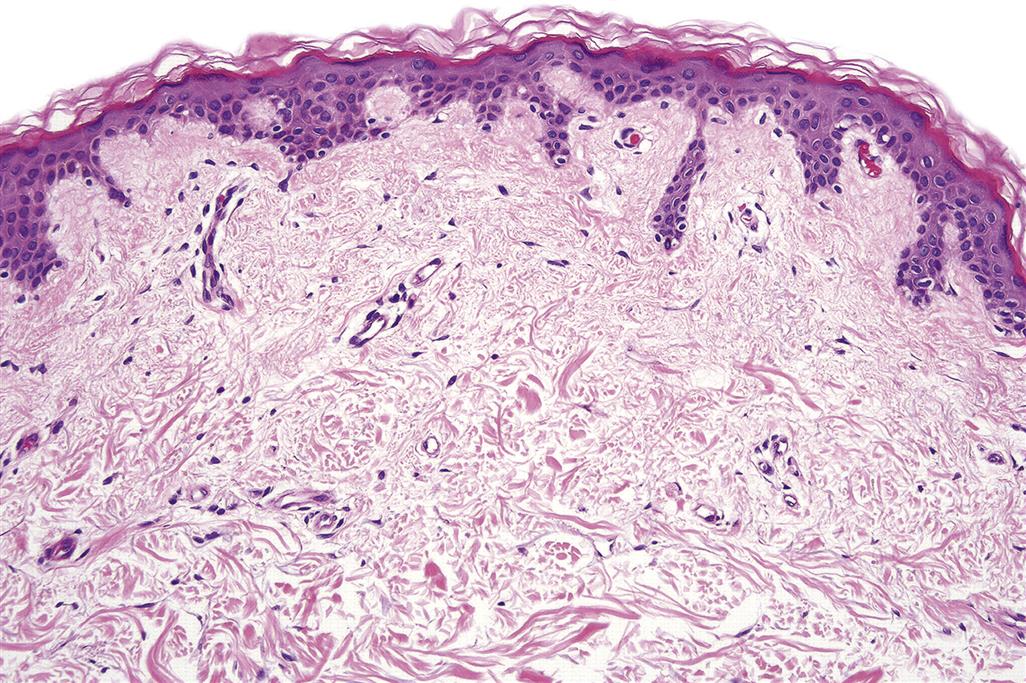

The Dermal–Epidermal Junction and Dermis

The dermal–epidermal junction (DEJ) aids in barrier function (both from and into epidermis), allows for firm attachment of epidermis to dermis, aligns cells of the epidermis, and serves as a base for reepithelialization in wound healing. The outermost DEJ is formed largely by basal keratinocyte plasma membranes and their attachments, hemidesmosomes (Figure 24.2). These link to the lamina lucida, the weakest zone of the DEJ. Elements of the lamina lucida are attached to the underlying lamina densa, a strong collagenous layer derived from collagens IV and V and cross-linking elements. Binding collagens to the dermis are anchoring fibrils (type VII collagen) of the sublamina densa, which attaches the DEJ to the dermis and contains a number of collagens, procollagens, and early elastic fiber components.

The dermis gives the skin tensile strength through collagen, contributes to movement by allowing stretch through elastic fibers, has immune regulatory capabilities, contains vascular and neurologic elements important for communication with the epidermis and environment, and forms the matrix for adnexa. The dermis largely determines the thickness of skin and is contiguous. Subregions of the dermis in humans are termed papillary and reticular. In species lacking epidermal rete ridges, these subregions are usually simply described as superficial and deep, respectively. The primary components of the dermis are collagens and elastins, conferring tensile strength, and proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans, and hyaluronans, which help dissipate pressure forces.

Nerves in the skin are both sensory and motor. Many sensory free nerve endings interact with specialized corpuscular units (mechanoreceptors such as Merkel cells and Pacinian or Meissner’s corpuscles, nocioceptors, thermoreceptors) responsible for pressure, sensing movement, itch/pain, and temperature. The hair follicles are also surrounded by sensory axons. Motor innervation is from sympathetic autonomic nerves and responds to either cholinergic or adrenergic stimuli. Adrenergic responses include vasoconstriction, apocrine gland secretion, and hair follicle positioning. Eccrine sweat glands are under cholinergic control; however, these glands are largely absent in most areas of nonhuman mammalian skin.

Dermal vasculature is rich and complex. Superficial, middle, and deep vasculature plexuses supply corresponding layers of the skin. Arteriovenous anastomoses are common in the skin of the extremities in particular, necessary for adaptation to frequent changes in temperature and blood pressure. These junctions respond to vasoconstrictors and vasodilators such as epinephrine and histamine. Many vessels of the skin have relatively thick walls compared to those of similar size in internal organs, a necessary adaptation for protection against the shear and pressure forces to which the skin is regularly subjected. Also present in the dermis are the fibroblast-like veil cells that define spaces for vessels within the dermis, surrounding microvasculature, and creating a perivascular space.

Cutaneous lymphatics arise as capillaries in the superficial dermis, but below the level of superficial blood capillaries. Gaps within the lymphatic vessels form channels by linking with the dermal matrix, directing excess interstitial fluids from the dermis into the lymphatic system. Lacking smooth muscle and pericytes, lymphatics of the dermis rely on subcutaneous muscle contraction, pressure of the surrounding matrix, and associated blood vessel movements to initiate flow of immunologic, waste, and even degraded pathogenic and xenobiotic materials away from the dermal interstitium. In the deeper subcutis, lymphatics have smooth muscle walls and are actively contractile directly directing flow of lymph to and from the skin.

The Subcutis

The subcutis is the adipose-rich tissue beneath the dermis responsible for attachment to underlying muscle, fascia, or periosteum. Connective tissue septa present throughout the subcutis facilitate movement and support dense vessel and nerve networks in the tissue. This layer also serves to absorb shock to underlying structures, shape the external features of the organism, and regulate temperature. The rich triglyceride stores of the subcutis can be utilized as an energy store and also serve to protect underlying tissues from temperature extremes. Visceral and subcutaneous adipose stores are also important in the secretion and targeting of various hormones and cytokines. In contrast to visceral adipose stores, it appears that the adipose tissue of the subcutis is better equipped for efficient lipolysis and less apt to secrete inflammatory cytokines, making it a compelling target for metabolic disease therapies.

The Adnexa

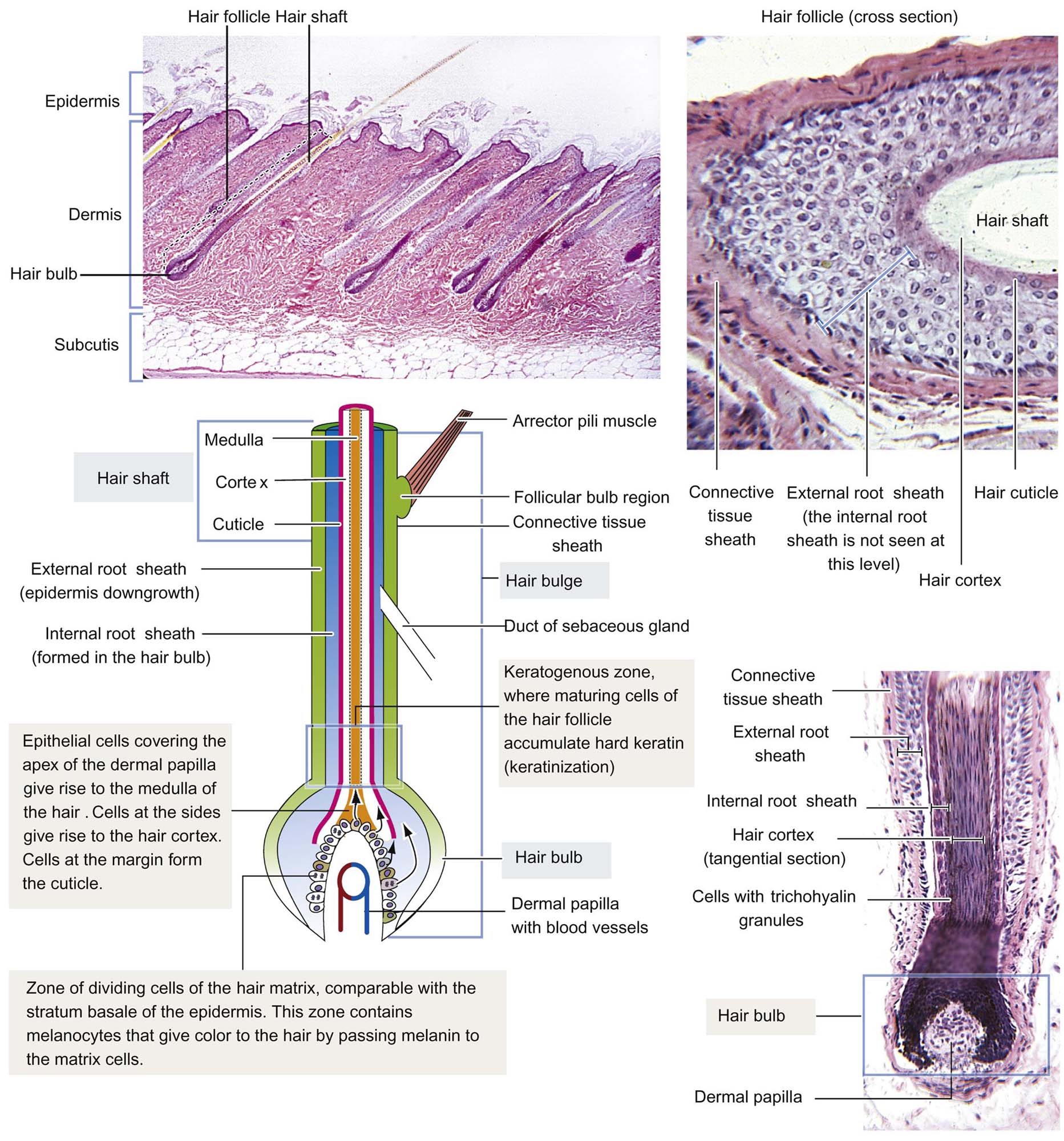

The cutaneous adnexal unit refers to a hair follicle, the associated arrector pili muscle, and associated glands. The hair follicle itself is essentially a down growth of the epidermis (Figure 24.3). The arrector pili muscle attaches to the hair follicle and has roles in piloerection and gland secretion that is under cholinergic control. The hair shaft is composed of an inner medulla, a surrounding cortex, and outer cuticle. The hair follicle has subanatomic regions known as the infundibulum (from the surface epidermis to the sebaceous gland duct entrance to the hair follicle), the isthmus (just below the infundibulum, from sebaceous duct to the arrector pili muscle insertion), and the inferior segment from the isthmus deep to the dermal papilla. The outer root sheath that contains the hair is contiguous with the surface epidermis.

The inner root sheath is attached to the cuticle of the hair and is distinguishable in tissue sections by the presence of eosinophilic cytoplasmic trichohyalin granules. The dermal papilla at the base of the follicle is a connective tissue-based appendage of the dermis itself that is covered by mitotically active epithelial cells that contribute to hair growth, the cells of the hair matrix. In humans and mice, a structure known as “the bulge” is present and attached to the outer root sheath, near the insertion of the arrector pili muscle. The bulge supplies the adnexal unit and, in some instances the surface epidermis (e.g., during wound healing), with pluripotent stem cells for regeneration. The bulge area may be absent in other species, with stem cells being present in infundibular and isthmus regions of the follicle itself, although some research does support bulge cell presence in the dog.

Hair growth is divided into the following stages: anagen (active growth), catagen (transition phase), telogen (resting stage), and exogen (shedding). During hair growth, an ordered array of keratinized cells is gradually pushed upward in the form of hair shafts. These cells give rise to hair by a process of terminal differentiation, analogous to, but more complicated than, the process described for epidermal cornification. Keratinization of hair follicle cells is of four morphologic subtypes: infundibular (like the surface epidermis, featuring keratohyalin), trichilemmal (important in identification of catagen hairs, with dense eosinophilic keratin “flames”), trichogenic/matrical (“ghost cell” keratinization), and medullary/inner root sheath (with deeply eosinophilic trichohyalin granules).

Two types of sweat glands, eccrine and apocrine, have been described in mammals. Eccrine glands participate in thermoregulation by secreting water and salts directly to the epidermal surface. Abundant throughout the skin in great apes and humans, in domestic and laboratory animals, the eccrine sweat glands are largely limited to the foot pads in dogs, and the nasal planum and carpus of pigs. These are merocrine glands composed of a long-coiled secretory tubule and a connecting long excretory duct that ends in the epidermis separate from the hair follicle; the epithelium lining both is simple columnar. The apocrine glands, which generally empty into the hair follicle at the level of the sebaceous gland, secrete a proteinaceous material that originates from the loss of cytoplasmic blebs from the apices of the simple columnar glandular cells. Their function is not clear, but they are related to accessory scent glands (e.g., porcine mental organ, eyelid/external ear glands, glands of anal sac in dogs, etc.) that produce attractant odors in some species. While distributed generally over the skin of most species, apocrine glands in humans are limited to armpits, groin, and nipples. Mammary glands are also modified apocrine glands specialized to produce milk.

Sebaceous glands develop from the neck or infundibulum of hair follicles and are composed of large polyhedral lipid-laden cells that undergo holocrine secretion after they are sloughed into a short duct. They form sebum, comprised of wax esters, squalene, free fatty acids, and triglycerides. Sebum is discharged into the infundibulum of the hair follicles and spreads to the epidermal surface where it helps to keep the SC moist. It also has antimicrobial function associated with its free fatty acids. There are large sebaceous glands in some species (e.g., chin glands in cats, tail glands in dogs, etc.) that also likely have marking, tactile, or pheromonal roles. Male hamsters have large aural sebaceous glands, making the hamster a popular animal model for testing compounds targeting sebaceous gland activity (Figure 24.4).

Evaluation of Toxicity

Physiologic and Morphologic Safety Evaluation Strategies and Techniques

Evaluation of cutaneous toxicity is essential for any therapeutic agents intended for use by topical administration. In addition, evaluation of potential adverse effects on the skin is necessary for therapeutic compounds that unintentionally come into contact with the skin (e.g., oral medications), exposure of skin from systemic exposure (i.e., distribution for systemically circulating drugs to the skin), and for nontherapeutic agents (i.e., cosmetics) that are applied to skin. Numerous global regulatory guidances (e.g., FDA, ICH, EMA) are available to provide guidance for the type of toxicity testing recommended for the different types of compounds under investigation. These guidances also extend to the various excipients used in preparation of formulations.

In vivo topical toxicity testing methods have focused on assessing skin irritation, cutaneous sensitization, ocular toxicity, and photosafety testing in various animal species and strains. The animal model selected and type of protocol used will depend on the objective of toxicity test. Unlike many other major organs, there are very distinct differences in skin structure among laboratory animal species and between these species and humans. Consequently, comparative evaluation of skin toxicity can be difficult to accomplish. The rabbit has been used for many years as the animal model of choice for evaluation of topical irritation potential. Although an extensive historical database exists for dermal irritation in the rabbit, this animal model has been shown to be more sensitive to primary irritants than human skin.

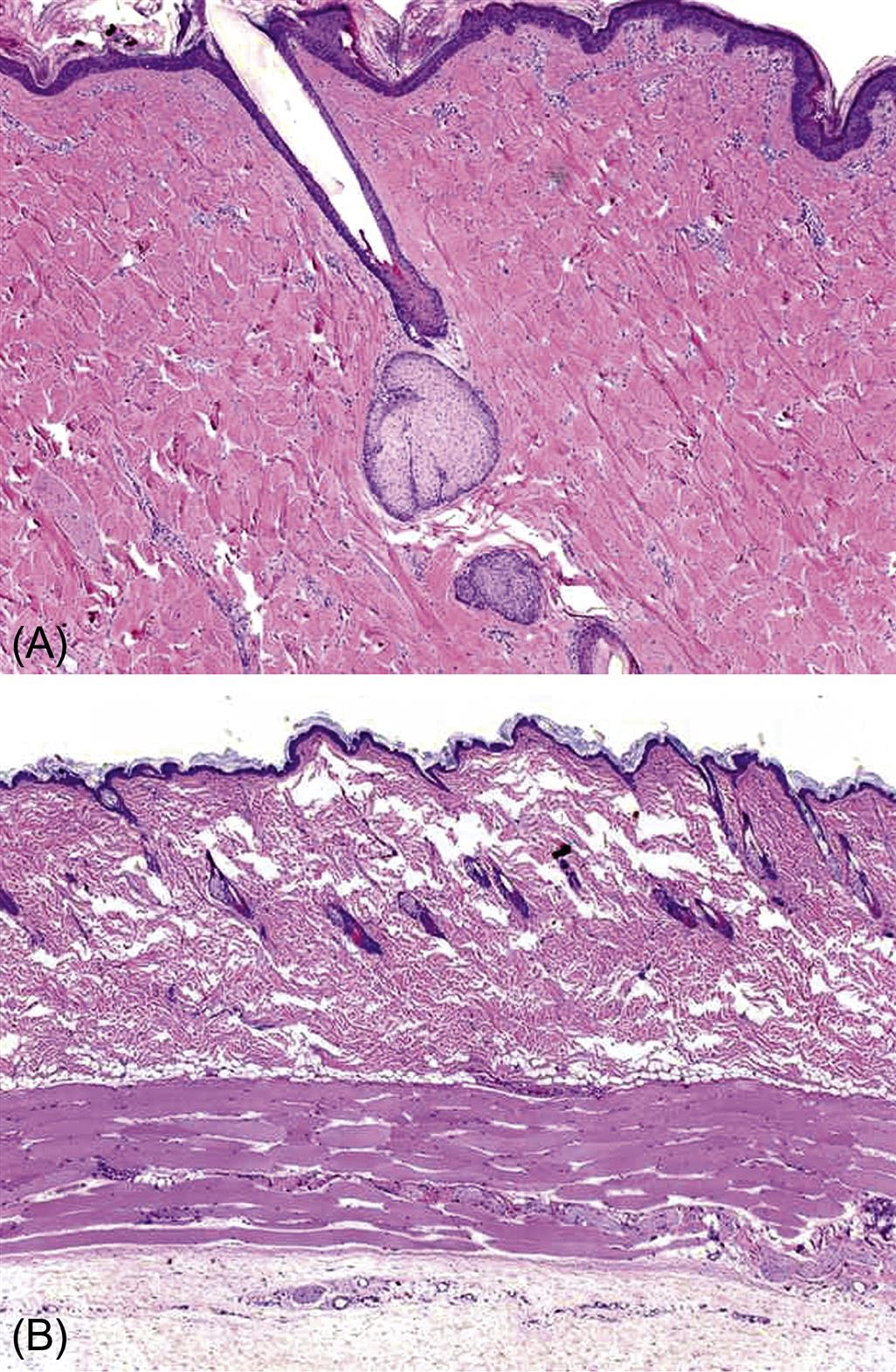

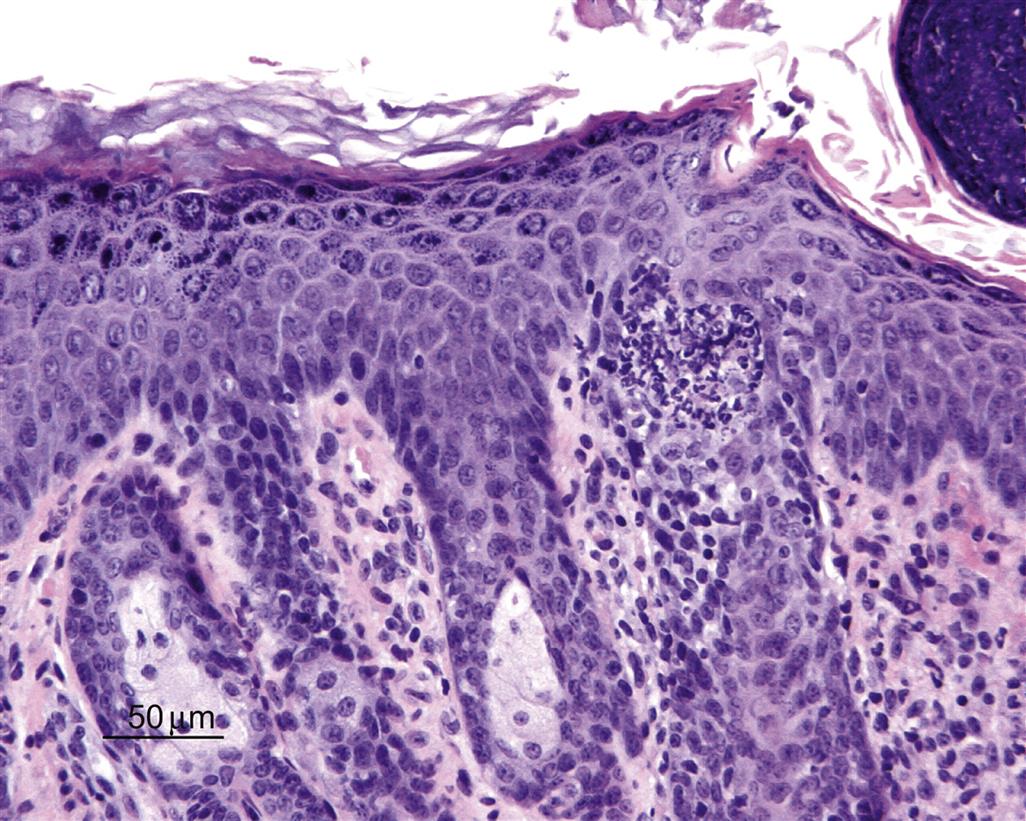

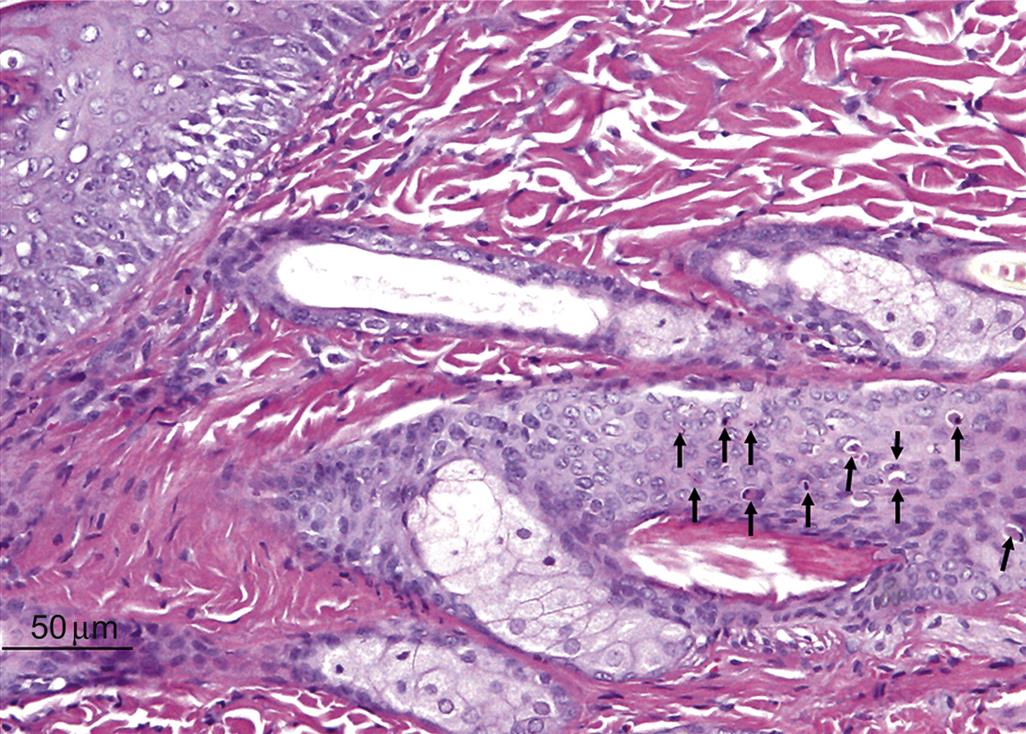

Most species used commonly in toxicity evaluations (mice, rabbits, rats, guinea pigs, dogs, and nonhuman primates) have relatively dense fur covering much of their bodies, and as such serve as poor comparators to human skin. The sparse hair covering of the laboratory minipig and the associated thicker epidermis most closely mimics the human skin, making it an attractive model in topical toxicity assessment (Figures 24.5 and 24.6).

The minipig has become the animal model of choice for assessing dermal irritation and tolerability of topical compounds on the basis of the greater similarity of morphologic and physiologic characteristics of pig skin to human skin. There are several breeds of laboratory minipig, but one of the most commonly utilized for regulatory toxicology is the Göttingen, based on its small size (about 45 kg as an adult). Similar to humans, the minipig has a papillary dermis with epidermal rete ridges. The cellular composition of the dermis and subcutis is also similar. Both humans and pigs have a relatively thick dermis with a large elastic fiber component. The dermis tightly adheres to the underlying subcutis and musculature, and the dermal and subcutaneous vasculature and lymphatics are rich and similarly distributed. Also similar to humans, minipig skin thickens and has increased permeability with reduced effectiveness at wound healing with age. Enzymatic properties and drug metabolism in the epidermis and some adnexa also are comparable, as are lipid composition of the epidermis and sebum. Skin pH is slightly higher in the minipig (pH 6–7) compared to human (pH 5). There are even spontaneous models of human skin disease such as melanoma and bullous pemphigoid that exist in minipig strains (the Sinclair and Yucatan, respectively). Yet the thicker SC and increased subcutaneous fat deposition in minipigs are points of dissimilarity with humans. There are also some differences in the enzymatic profile of the skin, in the distribution of eccrine and apocrine sweat glands, and in regulation of exogen as well. Still the minipig appears to be the species best suited for comparative toxicology of the skin.

In addition, other porcine models, in particular the Duroc/Yorkshire model, are considered the best animal models for recreating human wounds. This is based on collagen structure, which is remarkably similar to humans.

However, for certain evaluations, traditional laboratory animal models are still important. For example, the guinea pig is the animal model of choice for assessing allergic contact dermatitis potential of chemicals.

The route of administration selected in assessing the safety of topically applied compounds will depend on the end point of the assessment. Similar to therapeutic agents intended for oral or parenteral administration, in vivo toxicity testing should be evaluated in both rodent and nonrodent species. The rat is the rodent species of choice for evaluation of potential systemic toxicity of topical compounds, whereas the minipig is recommended as the nonrodent species. For topical therapeutic agents, there is also an expectation from regulatory agencies to evaluate both topical toleration and potential adverse systemic effects. For compounds intended for topical application, there have been numerous initiatives to reduce animal use in topical toxicity testing.

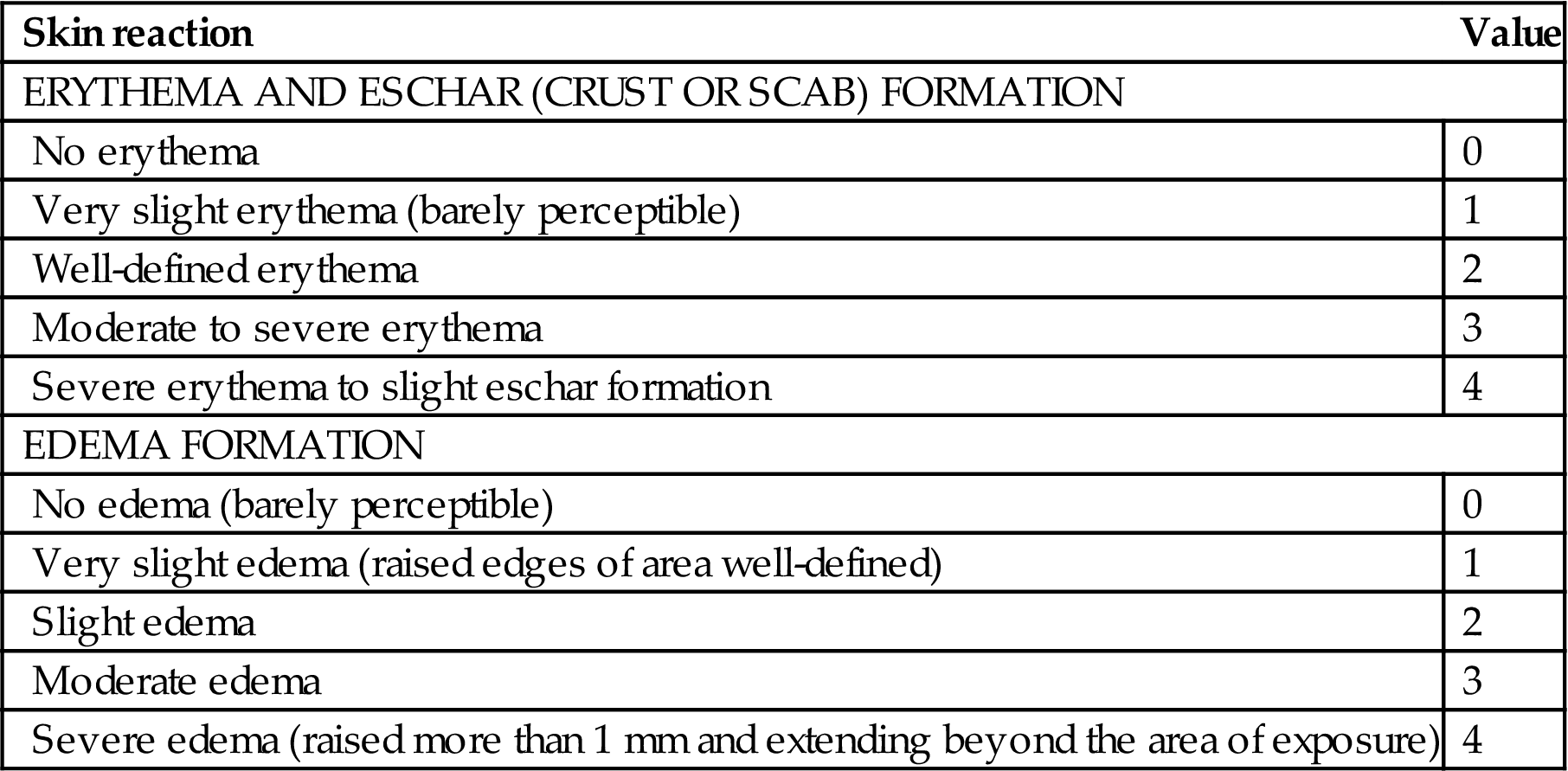

Assessment of Cutaneous Irritation

Evaluation of the irritation potential of topically applied compounds has utilized animal models of skin irritation. The Draize scale technique has been commonly utilized for quantitatively determining the degree of irritation caused by topical application of compounds and for providing a quantitative measure of comparison and differentiation of the irritation potential of various compounds (e.g., minor irritants vs major irritants). This technique was adapted in the United States by the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR 1980) and is legislated under provisions of the Federal Hazardous Substances Act. The Draize scale evaluates the degree of redness (i.e., erythema), crust or scab formation (i.e., eschar), and edema (Table 24.2). Human skin irritancy assessment is often required to complement animal irritancy testing in order to more precisely understand human risk (Table 24.3).

Table 24.2

The Draize Scale—Grading Values for Skin Reactions Following Topical Application of Potential Irritants

| Skin reaction | Value |

| ERYTHEMA AND ESCHAR (CRUST OR SCAB) FORMATION | |

| No erythema | 0 |

| Very slight erythema (barely perceptible) | 1 |

| Well-defined erythema | 2 |

| Moderate to severe erythema | 3 |

| Severe erythema to slight eschar formation | 4 |

| EDEMA FORMATION | |

| No edema (barely perceptible) | 0 |

| Very slight edema (raised edges of area well-defined) | 1 |

| Slight edema | 2 |

| Moderate edema | 3 |

| Severe edema (raised more than 1 mm and extending beyond the area of exposure) | 4 |

Modified from National Academy of Sciences (1977). From Haschek, W.M., Rousseaux, C.G., Wallig, M.A. (Eds.), 2013. Haschek and Rousseaux’s Handbook of Toxicologic Pathology, third ed. Academic Press (Elsevier), San Diego, CA, Table 55.2, p. 2233, with permission.

Table 24.3

Grading Scale in Human Skin Patch Test

| Grade | Lesion |

| 0 | No response |

| 0.5 | Indistinct erythema |

| 1 | Well-defined erythema |

| 2 | Erythema and edema |

| 3 | Vesicles and/or papules |

| 4 | Bulla or other severe reaction |

Modified from National Academy of Sciences, 1977. From Haschek, W.M., Rousseaux, C.G., Wallig, M.A. (Eds.), 2013. Haschek and Rousseaux’s Handbook of Toxicologic Pathology, third ed. Academic Press (Elsevier), San Diego, CA, Table 55.3, p. 2234, with permission.

Photosafety Testing

Chemicals or drugs that absorb light in the UVA (320–400 nm), UVB (290–320 nm), or the visible range (400–700 nm) are photoreactive. Photoactivation of a chemical may result in adverse effects termed photosensitivity reactions.

Photosafety testing is intended to identify agents with photosensitivity potential. Both in vitro and in vivo assays have been developed to assess the photosensitivity potential of photoreactive chemicals. Key considerations in the assessment of photosensitivity potential in these guidances are: photoirritation, photoallergenicity, photogenotoxicity, photocarcinogenicity, and photococarcinogenicity.

For photoreactive chemicals that absorb light in the UVA/visible light range, the 3T3 NRU assay is a validated in vitro assay for photoirritation potential (Table 24.4). Unfortunately, the 3T3 NRU assay will not work with strictly UVB absorbing chemicals, since UVB irradiation is cytotoxic to 3T3 cells and as such, requires in vivo testing. Human epidermis models (e.g., EpiDerm, EpiSkin, and SkinEthic) are being investigated as alternate in vitro models for utility in phototoxicity testing.

Table 24.4

Assessment of Phototoxic Potential Based on Photoirritancy Factor and Mean Photo Effect

| Photoirritancy factor (PIF) | Mean photo effect | Phototoxic potential |

| <2 | <0.1 | Nonphototoxic |

| >2 and <5 | >0.1 and <0.15 | Probably phototoxic |

| >5 | >0.15 | Phototoxic |

From Haschek, W.M., Rousseaux, C.G., Wallig, M.A. (Eds.), 2013. Haschek and Rousseaux’s Handbook of Toxicologic Pathology, third ed. Academic Press (Elsevier), San Diego, CA, Table 55.4, p. 2234, with permission.

In vivo phototoxicity testing may be conducted in guinea pigs, rabbits, hairless mice, or hairless guinea pigs. In this assay, the application site on the test species is exposed to UV irradiation from a solar simulator. After a period of time to allow for absorption of the test article, the Draize scale is used to determine the phototoxic response by grading of irritation potential. In a review of concordance of toxicity of pharmaceuticals in humans and animals, phototoxicity response in guinea pigs correlated well with that in humans.

Photoallergenicity is typically evaluated in vivo in guinea pigs. The Buehler Guinea Pig Sensitization assay (with exposure to simulated light) is preferred over the Guinea Pig Maximization Assay, which although considered more sensitive than the Buehler assay, is associated with subcutaneous reactions attributed to the use of adjuvant in this assay. It should be noted that although European regulatory guidances recommend conducting photoallergenicity testing, the FDA does not recommend this assay since convincing data do not support it.

Although photogenotoxicity testing was included in previous regulatory guidance recommendations, it is now generally accepted by regulatory agencies that photogenotoxicity testing not be conducted since there are too many false positives, even with compounds that are not photoreactive.

Photocarcinogenicity testing may be required for topical compounds that are used chronically, are phototoxic, and are topically applied or if there is indication for concern based on the class of compound. However, photocarcinogenicity testing may not be needed for compounds that are photoirritants if a warning is provided in patient information. Photoco-carcinogenic potential must also be taken into consideration for chemicals that may not be photoreactive but may influence carcinogenicity through immunosuppressive effects (e.g., cyclophosphamide) or altering the optical properties of the skin (e.g., certain emollients). SKH-1 hairless mice are used as models of UVR-induced carcinogenesis and develop skin tumors that are considered relevant to the study of human skin cancer.

Response to Injury

General Mechanisms of Response to Injury

The skin, like other organ systems, has a relatively stereotypic response to injury, regardless of the specific mechanism underlying the insult. Despite the limited range of response, there is still a great deal that can be ascertained from the different morphologic, physiologic, and molecular alterations that arise in response to injury.

One of the skin’s primary functions is to serve as a physical and physiologic protective barrier against injury from the external environment and from loss of water and solutes from the body. When the skin is exposed to irritants, such as xenobiotics, infectious agents, or UVR, that may damage or disrupt this barrier, it mounts an inflammatory and proliferative response in order to prevent further damage and to restore a morphologically and physiologically functioning barrier.

This barrier disruption manifests in the form of both morphologic and physiologic alterations that will vary depending on the degree of barrier damage, and to some extent on the specific irritant, although most pathophysiologic responses are generalized and independent of the specific initiating factor(s). A core premise underlying the skin’s response to injurious stimuli is that the epidermis, and particularly epidermal keratinocytes and DCs, including LCs, are central to the initiation of the skin’s response to injury.

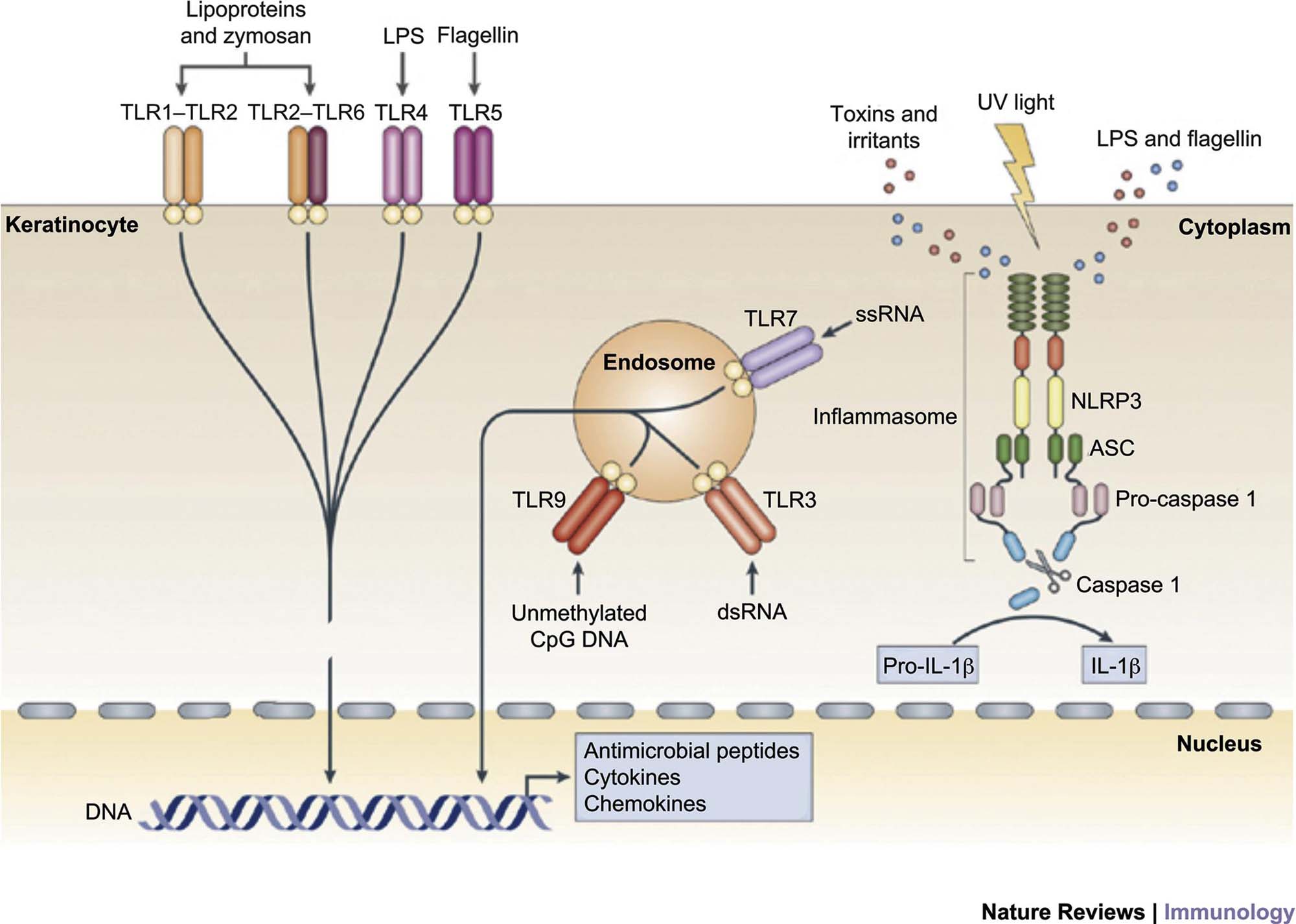

The hypothesis that the epidermal keratinocyte is a primary initiator of the skin’s response to noxious stimuli has gained widespread acceptance. Epidermal keratinocytes can recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) of microbial origin, and danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), such as xenobiotics and other irritants through Toll-like receptors (TLRs), including TLR-1, TLR-2, TLR-4, TLR-5, and TLR-6 on their surface and TLR-3 and TLR-9 in their endosome, that trigger an inflammatory cascade leading to the generation of antimicrobial peptides such as β-defensins, cathelicidins, and S100 family proteins, pro-inflammatory chemokines such as IL-8, CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11, CCL27, and CCL20, and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF, IL-6, and IL-18.

These chemokines and cytokines recruit and activate leukocytes and convert the initial innate immune response to an adaptive immune response. In addition, keratinocytes express nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich repeat-containing (NLR) proteins that recognize cytoplasmic PAMPs, DAMPs, and UVR. When engaged, NLRs trigger a pro-inflammatory signaling pathway through a large multiprotein complex termed an inflammasome formed by an NLR, an adaptor protein termed ASC, and pro-caspase 1. Inflammasome assembly activates caspase 1, which in turn cleaves pro-interleukin-1β (pro-IL-1β) to active IL-1β (Figure 24.7).

The immune response triggered by keratinocyte activation is believed to be central to the skin’s response to a wide range of stimuli, and leads to the stereotypic morphologic response(s). Even the immune-mediated/autoimmune disease, psoriasis, is now believed to be at least partially caused by inappropriate or poorly regulated activation of epidermal keratinocytes, which in turn leads to inflammation and the hallmark morphologic changes associated with this condition. The ability of cytokines such as IL-22 and oncostatin M to induce morphologic and differentiation features in keratinocytes that mimic those found in psoriatic epidermis in three-dimensional reconstituted human epidermal models skin in the absence of blood vessels and leukocytes reinforces the hypothesis that epidermal keratinocytes are central to the initiation of cutaneous inflammation as well as the initiation of cutaneous response to injury, infection, and toxicity.

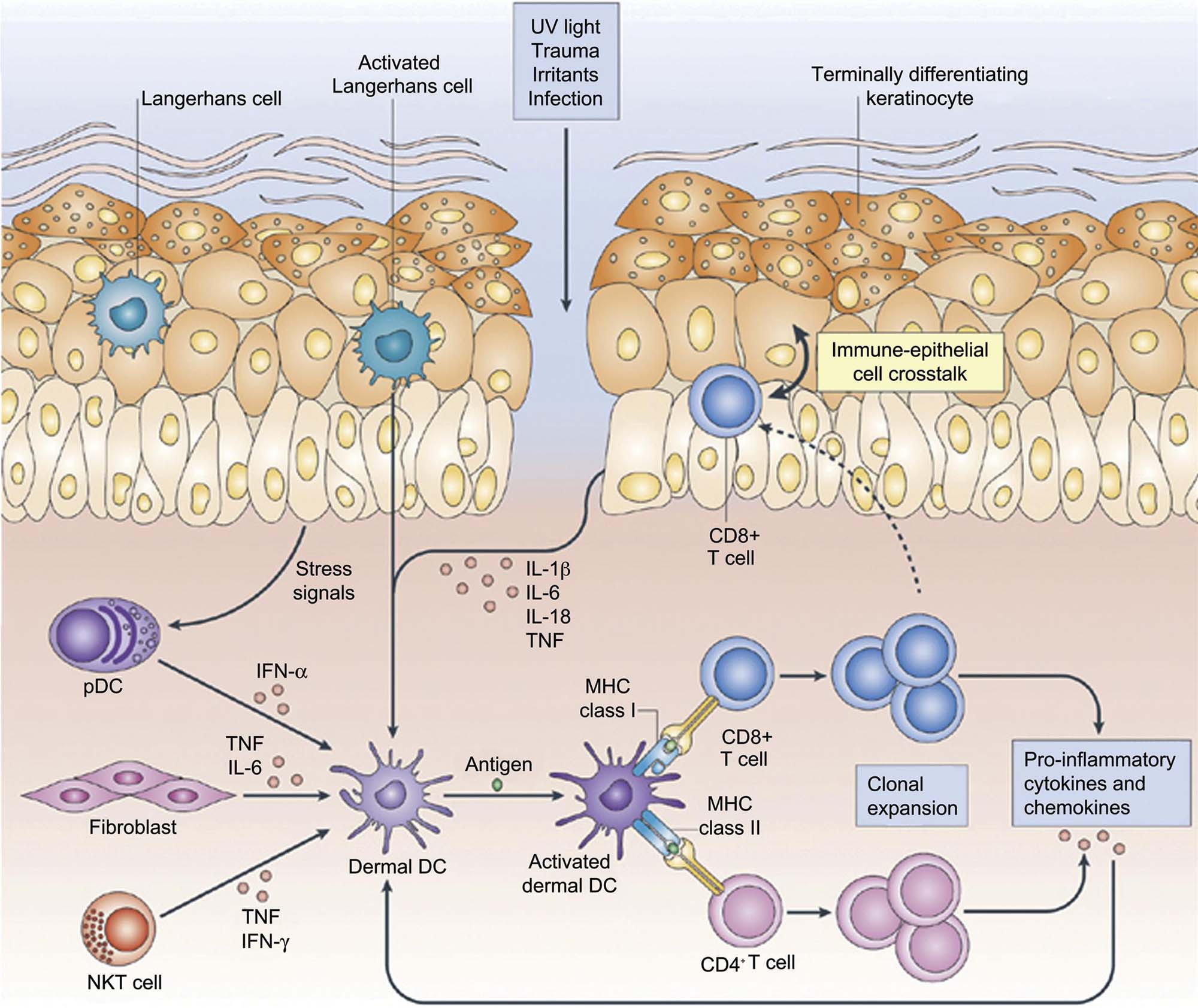

Skin-resident DCs, which are bone marrow–derived, have also been implicated as playing an important role in the initiation of the cutaneous inflammatory response to various noxious stimuli. There are several different populations of skin-resident DCs that are defined by their location (epidermal vs dermal), their cell surface antigen expression, and most importantly, by their functionality. LCs are the primary epidermal DC population, and express CD1a and the c-type lectin, langerin (DC207) in association with ultrastructurally visible racquet-shaped organelles called Birbeck granules. Immature LCs are the immune sentinel cells in the epidermis equipped for antigen capture via TLR and c-type lections such as langerin. Upon antigen capture and activation, these cells become mature LCs, expressing major histocompatibility class (MHC) I and MHC II and costimulatory molecules important in the adaptive immune response, and migrate to the inner paracortex of draining lymph nodes to present antigens to T cells.

Because of their role in cutaneous antigen presentation, LCs are believed to be important in the initiation of cutaneous cell-mediated immune responses, such as those responsible for allergic contact dermatitis. More recently, data from mice deficient in LCs suggest that LCs may decrease rather than enhance inflammation, leading to the hypothesis that LCs may be involved in the generation of tolerance rather than in the initiation of inflammation.

A third set of cells implicated in the initiation of the cutaneous immune response are skin-resident T lymphocytes, found both within the epidermis as well as in the dermis. Epidermal resident T cells are primarily CD8+ α/β memory T cells, and are often found in close proximity to LCs. Dermal resident T cells are also mostly memory cells, but are roughly equally distributed between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Dermal resident T cells express cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen, and gain skin-homing properties after contact with resident DCs.

In addition to cutaneous resident T cells, all three major types of CD4+ helper T lymphocytes, Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells have been found in the skin during various inflammatory conditions. Initially, Th1 helper T cells, driven by IL-12 and producing IFNγ and related cytokines, were believed to be the primary T cells involved in the cutaneous immune response and cutaneous response to injury. More recently, IL-23-driven Th17 cells have been recognized as being essential in host immune defense against many bacterial and fungal pathogens at both cutaneous and mucosal surfaces. IL-17 and IL-22, cytokines produced by Th17 cells, upregulate keratinocyte production of antimicrobial peptides. Thus, Th17 cells and their cytokines link the adaptive immune response to the innate immune response of keratinocytes in order to optimize the host immune response to cutaneous pathogens.

Skin-resident T cells are believed to play a major role in skin immune homeostasis and surveillance, and have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. A specific subset of skin-homing T cells that produce IL-22 but not IL-17 or IFNγ, termed Th22 cells, has been recently identified in the skin of patients with atopic dermatitis. Th22 cells produce the epithelial-specific cytokine, IL-22, which induces keratinocyte proliferation, differentiation, and production of antimicrobial peptides such as β-defensins and S100 family proteins, pro-inflammatory chemokines such as IL-8, CXCL1, and CXCL7, and cytokines and growth factors involved in epidermal regeneration such as IL-20 and vascular endothelial growth factor. IL-22 producing Th22 cells provide further evidence for the cross-talk between the adaptive immune system and the innate immune system, particularly epidermal keratinocyte. Thus, the current model for the cutaneous response to injury, regardless of the specific type or etiology of the injury, is initiated by epidermal keratinocyte recognition of PAMP or DAMPs via engagement of TLRs and/or NLRs, thus triggering pro-inflammatory signaling pathways and an inflammatory cascade that leads to the generation of antimicrobial peptides such as β-defensins and cathelicidins, pro-inflammatory chemokines such as IL-8, CXCL1, CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11, and cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF, IL-6, and IL-18. These keratinocyte-derived chemokines and cytokines further recruit and activate DCs and other leukocytes to elaborate additional cytokines and chemokines, such as IFNα from pDCs and IL-12 and IL-23 from dermal DCs. These mediators further recruit and activate T lymphocytes of both the Th1 and particularly the Th17/Th22 lineages to release pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFNγ, IL-17, and IL-22. These mediators then converts the initial innate immune response to an adaptive immune response, and provide cross-talk between the two arms of the immune system (Figure 24.8). This immune response is believed to be central to the skin’s response to a wide range of injurious stimuli, and leads to the morphologic responses that are described in this chapter.

Specific Cutaneous Morphologic Lesions and Patterns of Injury

The histopathologic interpretation of lesions in the integument, is based on the basic morphologic reaction patterns in the integument as much and perhaps more so than in other organ systems. Pattern recognition for the diagnosis of inflammatory conditions in the skin was pioneered by A. Bernard Ackerman in his seminal book Histologic Diagnosis of Inflammatory Skin Diseases: A Method Based on Pattern Analysis, and has been extensively used for the recognition and diagnosis of dermatitides in both human and veterinary pathology since.

These basic morphologic reaction patterns serve as a very useful device for the recognition of specific cutaneous morphologic responses to injury. In this section, the INHAND (International Harmonization of Nomenclature and Diagnostic Criteria for Lesions in Rats and Mice) diagnostic classification scheme and nomenclature for proliferative and nonproliferative lesions in mouse and rat integument is followed. The INHAND project is a joint initiative of the societies of toxicological pathology from Europe (ESTP), Great Britain (BSTP), Japan (JSTP), and North America (STP). Its aim is to develop an internationally accepted nomenclature for proliferative and nonproliferative lesions across organ systems in laboratory rodents. The standardized INHAND nomenclature followed here, as well as additional information, is available at Mecklenburg et al. (2013) and at http://www.goreni.org.

Nonproliferative Lesions of the Epidermis

Epidermal atrophy is characterized by thinning of all noncornified epidermal layers with a corresponding decrease in nucleated keratinocytes, such that the distinction between SB, SS, and SG may no longer be apparent. Substances that decrease normal keratinocyte proliferation and metabolic activity, such as topical corticosteroids, are a common cause of epidermal atrophy.

Epidermal erosion and ulceration are characterized by loss of superficial epidermal layers (erosion) or complete loss of the epidermis with disruption of the epidermal basement membrane (ulceration). Erosions are always due to superficial epidermal trauma, and are most commonly associated with trauma from scratching. Ulceration is also often caused by superficial epidermal trauma, but may also be the result of toxicity or a necrotizing dermatitis. Ulceration due to toxicity needs to be differentiated from ulcerative dermatitis, which occurs spontaneously in certain strains of mice and rats, most commonly in the C57BL/6 mouse.

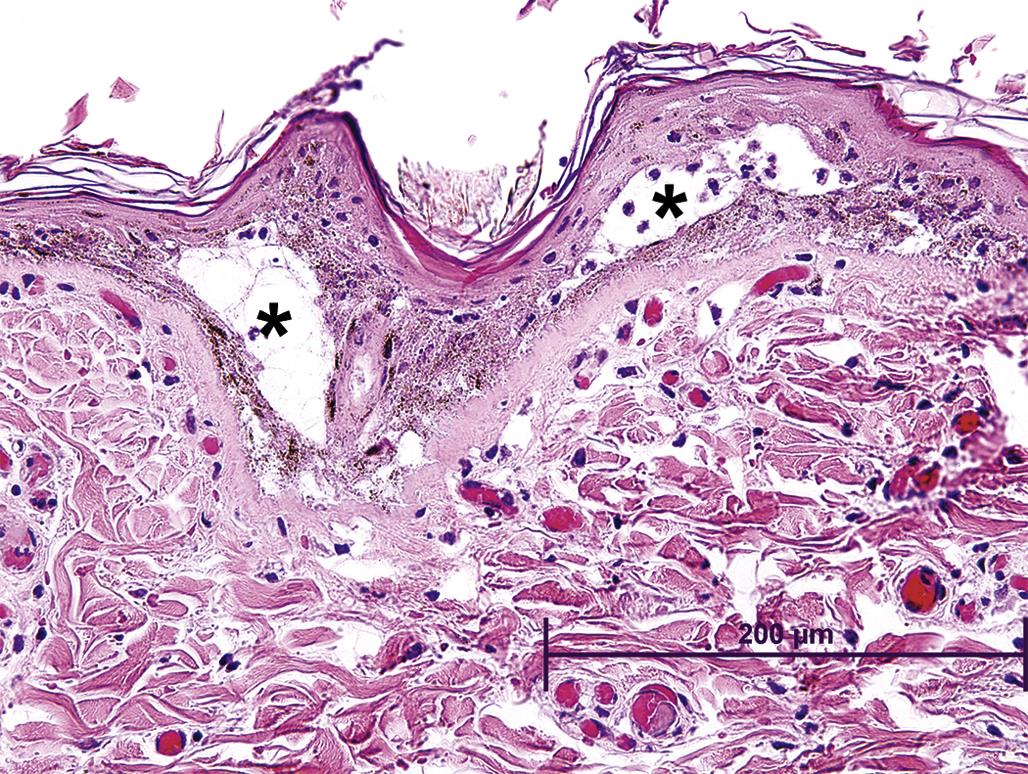

Epidermal necrosis can be classified as either single cell or full-thickness necrosis. Epidermal necrosis is a hallmark feature of drug hypersensitivity reactions or drug eruptions, where it can occur as single cell necrosis and is termed erythema multiforme, or as full-thickness epidermal necrosis, where it is termed toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Single cell necrosis of keratinocytes may be further subdivided into apoptosis, or programmed cell death, and dyskeratosis, which is the occurrence of terminal keratinization of individual keratinocytes that has not occurred as part of the orderly process of epidermal keratinization; apoptosis cannot be differentiated from dyskeratosis on H&E stained sections. Apoptotic keratinocytes in UV light-exposed epidermis are often referred to as “sunburn cells.”

Vesicular change refers to intracellular edema of keratinocytes and is characterized by increased size and pallor of keratinocytes with peripheral displacement of the nucleus. In the SB, synonyms are hydropic degeneration and vacuolar degeneration, while in the suprabasal epidermis it is often referred to as ballooning degeneration. If vesicular change is severe, keratinocytes may rupture and form intraepidermal vesicles.

In contrast to vesicular changes, spongiosis refers to intercellular edema between epidermal keratinocytes and is characterized by widened intercellular spaces with accentuation of desmosomes. Severe epidermal spongiosis may lead to rupture of intercellular desmosomes and the formation of intraepidermal vesicles. Spongiosis is a common feature of skin inflammation.

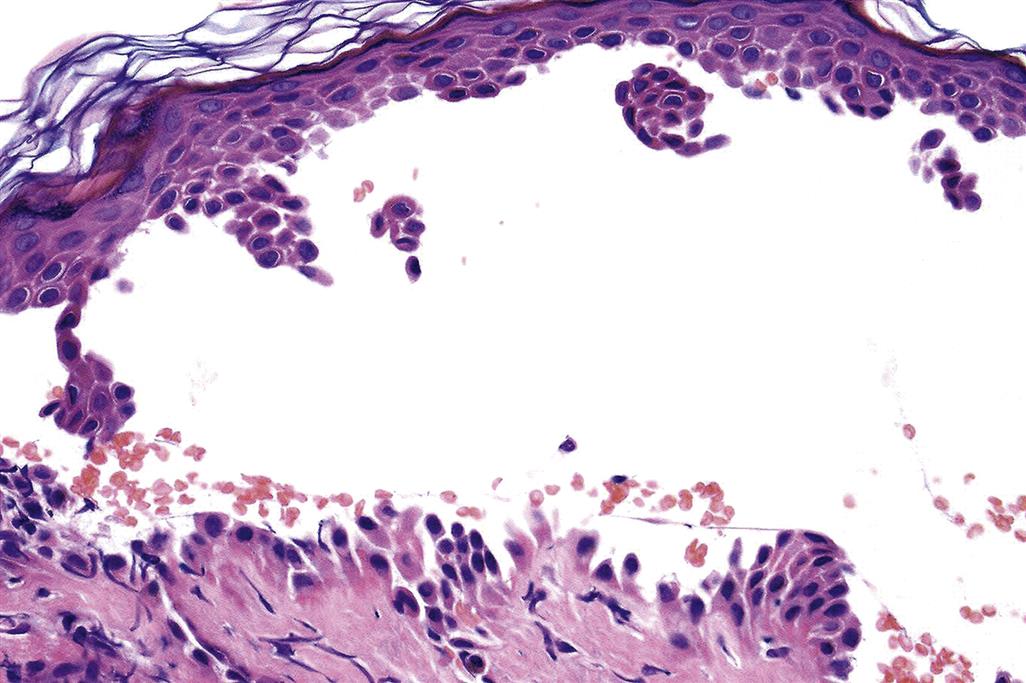

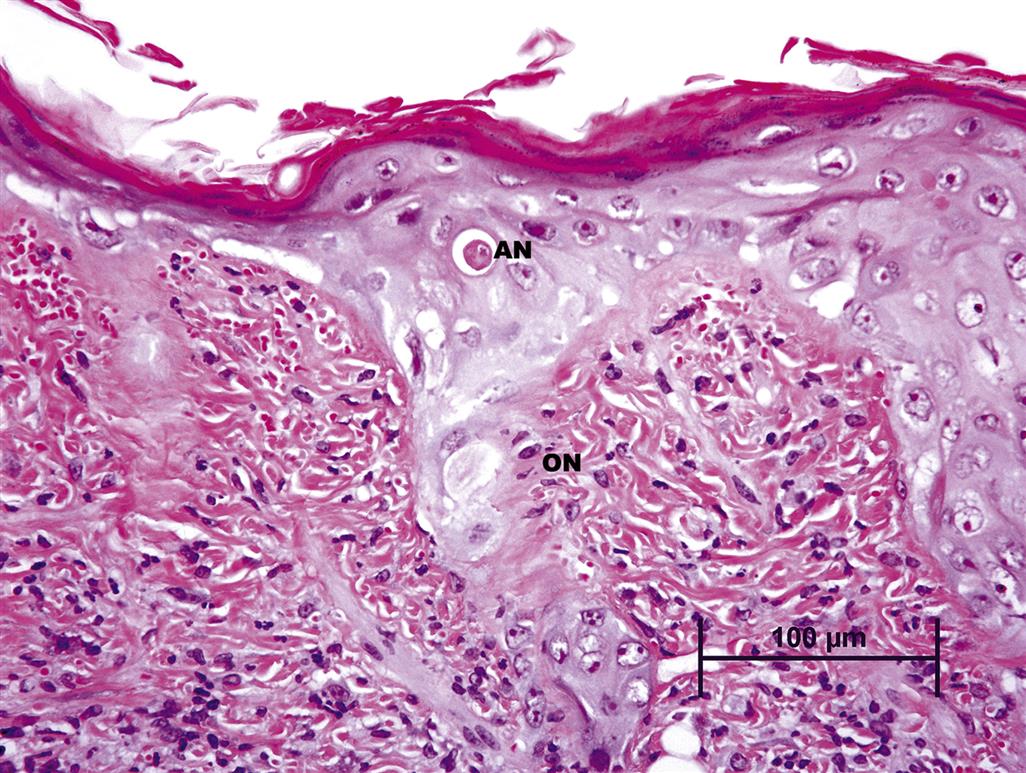

A vesicle is an intra- or subepidermal cavity or cleft filled with fluid and is also referred to as a bulla. It occurs following loss of cohesion between epidermal keratinocytes or between epidermis and dermis, resulting in the formation of a fluid-filled cavity. Vesicles that are located between the SB and the underlying mesenchyme are termed clefts.

A pustule, also referred to as a microabscess, is a focal intraepidermal accumulation of leukocytes, and is commonly found as a feature of generalized skin inflammation. In contrast, leukocytes which are diffusely, rather than focally infiltrating throughout the epidermis are referred to as exocytosis. Pustules that are filled with isolated rounded keratinocytes with a normal nucleus are referred to as acantholytic pustules. A predominantly neutrophilic pustule in a CD45RBHi SCID mouse model of psoriasis is illustrated in Figure 24.9.

Hyperkeratosis refers to an increase in the thickness of the SC, and is classified as either orthokeratotic, composed of normal anucleate corneocytes, or parakeratotic, composed of abnormal nucleated corneocytes. Hyperkeratosis frequently accompanies epidermal hyperplasia and is often associated with chronic epidermal irritation. When the hyperkeratotic SC contains leukocytes or a proteinaceous exudate, it is commonly referred to as a crust.

A squamous cell cyst is an intradermal cyst lined by a wall composed of orderly stratified squamous epithelium with a lumen filled by concentrically arranged lamellar keratin. Squamous cell cysts can spontaneously occur in mice, particularly in the B6C3F1 strain.

Nonproliferative Lesions of the Cutaneous Adnexa

Many of the lesions found in cutaneous adnexa have been previously described under the epidermis, such that only features unique to the adnexal condition will be covered in this section.

Adnexal atrophy is defined by a marked reduction in follicular and sebaceous gland size and cell number well beyond that found physiologically during the normal telogen stage of the hair cycle. It is characterized by small remnants of follicles and sebaceous glands appearing as strands of keratinocytes surrounded by a thickened connective tissue sheath. Most follicles lose their hair shaft, and dermal atrophy or scarring may be present. Hair follicles lose cells when they undergo regression in the catagen stage of the hair cycle. Therefore, hair follicle atrophy must be distinguished from catagen and telogen stages of the hair cycle. Hair follicle atrophy can be caused by a number of different compound classes such as antiproliferatives and steroid hormones.

Follicular dysplasia is an abnormality in the shape of the hair follicle and/or the hair shaft with no evident reduction in size. While for the epidermis dysplasia usually denotes a preneoplastic proliferative change, in cutaneous adnexa it is primarily describing a malformation of the adnexal structure. Many genetically modified mice, including mice null for growth factors and their receptors such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (termed Waved-2), transforming growth factor-α (termed Waved-1), fibroblast growth factor-5 (termed Angora), and keratinocyte growth factor (termed Rough), have been described that exhibit various forms of congenital hair follicle malformation. The loss of pigment from hair follicles may also be classified as a dysplasia.

Follicular necrosis is similar to epidermal necrosis, and is characterized by degeneration of follicular keratinocytes, either as single cells (single cell type) or as multiple cells (diffuse type). Chemotherapeutic agents such as paclitaxel and doxorubicin induce follicular necrosis of the single cell type, thereby inducing alopecia. Follicular keratinocyte single cell necrosis in a Lewis rat given a kinase inhibitor systemically is illustrated in Figure 24.10. Hair follicle dystrophy can be classified as a form of necrosis, as follicular keratinocytes undergo uncoordinated vacuolar degeneration or apoptosis.

Adnexal, and particularly follicular inflammation, is classified according to its pattern or location (perifollicular, intrafollicular, luminal, mural), similarly to inflammation affecting the dermis. Inflammation can also be subcategorized according to its character (lymphocytic, plasmacytic, neutrophilic, eosinophilic, and granulomatous). Interface folliculitis refers to perifollicular and mural inflammation that is generally associated with distinct necrosis of follicular keratinocytes. Follicular inflammation that has penetrated through the follicular wall leading to follicular rupture and marked inflammation in the surrounding dermis and connective tissue due to a foreign body inflammatory response to the hair shaft and follicular keratins is termed furunculosis.

Proliferative Nonneoplastic Lesions of the Epidermis

Squamous cell hyperplasia is also referred to as acanthosis or epidermal hyperplasia and is characterized by increased epidermal thickness, primarily in the SS and SG, due to an increased number of epidermal keratinocytes, primarily in the SS. As mentioned earlier, hyperplasia is frequently accompanied by hyperkeratosis. In addition, rete ridge formation is often present, but the epidermal basement membrane remains intact. In the dysplastic type of squamous cell hyperplasia, the nonkeratinized layers of the epidermis are irregularly thickened and differentiation between SB, SS, and SG is lost. Cellular atypia is not present, and the epidermal basement membrane still remains intact. Squamous cell hyperplasia typically occurs as a response to a variety of insults including inflammation, toxic irritation, repeated abrasion of the superficial SC, or prolonged exposure to UV light.

Proliferative Nonneoplastic Lesions of the Adnexa

Sebaceous cell hyperplasia is characterized by enlargement of sebaceous glands with maintenance of the normal glandular architecture. Enlarged sebaceous gland acini contain increased cells that are primarily mature, sebum-containing cells. Sebaceous cell hyperplasia frequently accompanies squamous cell hyperplasia, and both are commonly seen with chronic inflammation.

Proliferative Nonneoplastic Lesions of the Dermis

Pigment cell hyperplasia is an accumulation of pigmented melanocytes within the dermis between hair follicles and sebaceous glands. Pigment cell hyperplasia has been observed in some initiation–promotion and skin-painting studies in mice. It can also occur during chronic dermal inflammation, where it needs to be distinguished from the dermal accumulation of pigment-laden macrophages, or melanomacrophages, that have engulfed melanin pigment.

Neoplastic Lesions and Carcinogenesis Models

Carcinogenesis Models

The multistage model of mouse skin carcinogenesis is a very well-established model that has greatly aided in the identification of the underlying cellular, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms associated with the various stages of epithelial carcinogenesis. In this model, tumor development occurs via three distinct stages: initiation, promotion, and progression. Tumor initiation involves induction of a mutation of a critical gene or genes. At the initiation stage, there are no demonstrable histopathologic alternations present. The Ha-ras gene appears to be a primary target gene for the initiation stage in this carcinogenesis model and becomes mutated following exposure to 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA). Following initiation, tumor promotion occurs by increased expression of growth regulatory genes and sustained stimulation of epidermal keratinocyte proliferation and hyperplasia. These changes are believed to result from epigenetic mechanisms such as activation of the cellular receptor, protein kinase C.

There are three mouse models that have been commonly used for cutaneous carcinogenesis evaluation, although none are currently approved for stand-alone cutaneous carcinogenicity assessment by regulatory agencies: the Tg.AC (v-Ha-ras) transgenic mouse, the rasH2 transgenic mouse, and the SENCAR mouse. The Tg.AC and rasH2 mouse models are both rasHa transgenic lines. Tg.AC mice are hemizygous for a mutant v-Ha-ras transgene.

The Tg.AC model was developed using an inducible ζ-globin promoter to drive the expression of a mutated v-Ha-ras oncogene, and is regarded as a genetically initiated model. The transgene is transcriptionally silent until activated by full-thickness wounding, UV irradiation, or topical application of specific carcinogens to the shaved dorsal surface of Tg.AC mice to induce epidermal squamous cell papillomas or carcinomas. Hence this is a reporter phenotype that defines the activity of the carcinogen.

The rasH2 mouse, also known as Tg.rasH2, was created by insertion of a human c-rasHa transgene driven by its own promoter. Hemizygous rasH2 mice respond with greater sensitivity to carcinogens than nontransgenic mice and are similarly recommended for genotoxic and nongenotoxic carcinogen identification.

SENCAR mice are not genetically engineered; rather the line was selected over eight generations by for increased skin tumor multiplicity and decreased tumor latency in response to DMBA and TPA treatment. SENCAR mice have an approximately 10 to 20-fold increase in sensitivity to DMBA initiation and 2 to 3-fold increase in sensitivity to TPA promotion compared with the parental CD-1 stock. The SENCAR mouse is a commonly used short-term model system for evaluating the promoting or initiating activity of test items for two-stage skin carcinogenesis in mice. These mice respond rapidly and sensitively with skin tumors following topical application of a single low dose of an initiating agent, typically a mutagenic carcinogen, followed by multiple applications of a tumor promoting agent.

When evaluated for sensitivity and predictability of mouse skin models for carcinogenic hazard identification, all of the three mouse models respond similarly, with mild inflammation and epidermal squamous cell proliferation and hyperplasia, to several weeks of treatment with topical carcinogens. All of the three mouse models are also similar in their development of the reporter phenotype: the development of squamous cell papillomas following extended carcinogen treatment. All have been shown to be fairly predictive of carcinogenic potential in humans.

Cutaneous tumors, particularly those derived from the epidermis and cutaneous adnexa, are not uncommon spontaneous findings in rodents, so attention must be paid to the potential occurrence of spontaneous tumors in the commonly used mouse models of skin carcinogenesis. In these mouse models, the typical carcinogen-induced tumors are squamous cell papilloma with malignant progression to squamous cell carcinoma, such that it is essential to differentiate these carcinogen-induced epidermal keratinocyte-derived epithelial tumors from other spontaneously occurring tumors derived from epidermal keratinocytes as well as spontaneously occurring tumors derived from cutaneous adnexal epithelia.

Neoplastic Proliferative Lesions of the Epidermis

Squamous cell neoplasms are the typical tumors that occur in all mouse skin tumor models, and arise first as squamous cell hyperplasia (described earlier) followed by the development of squamous papillomas, described here, and finally malignant squamous cell carcinomas.

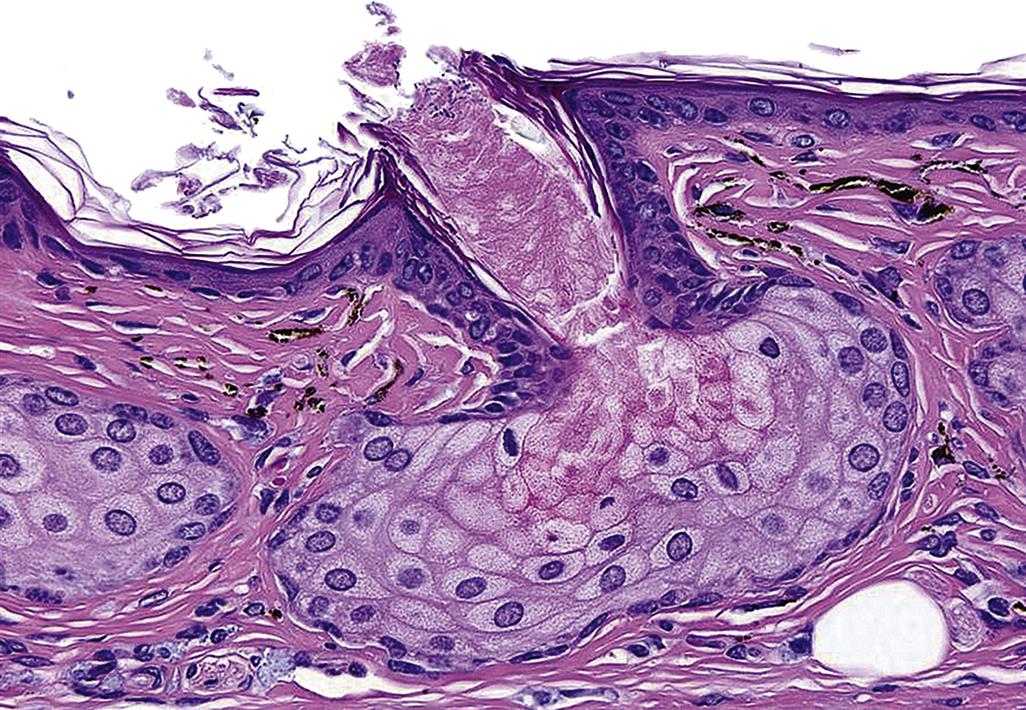

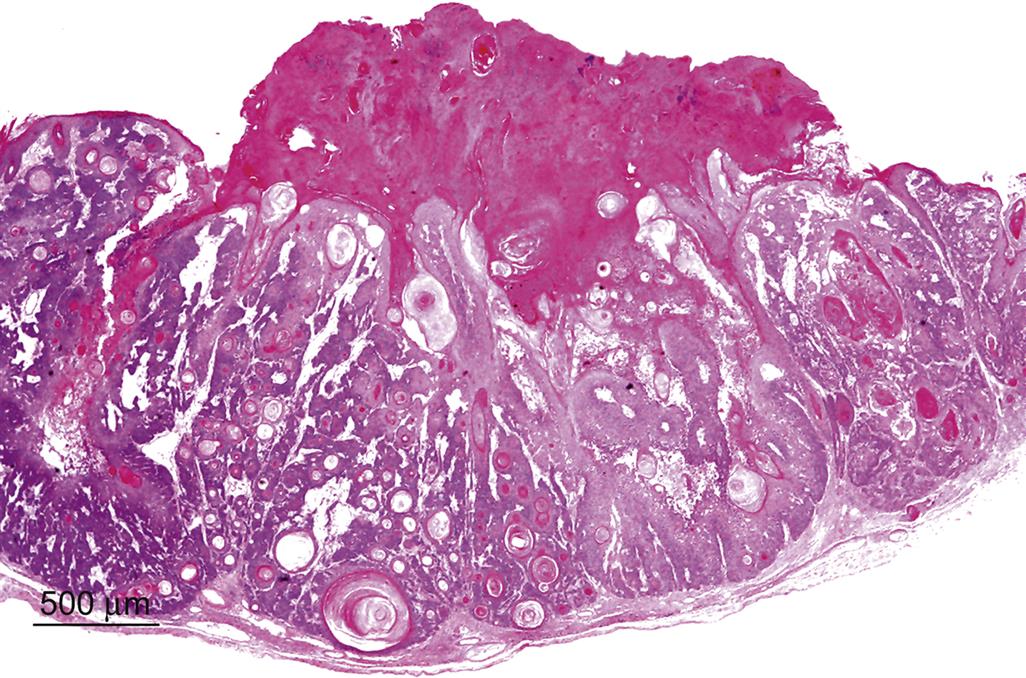

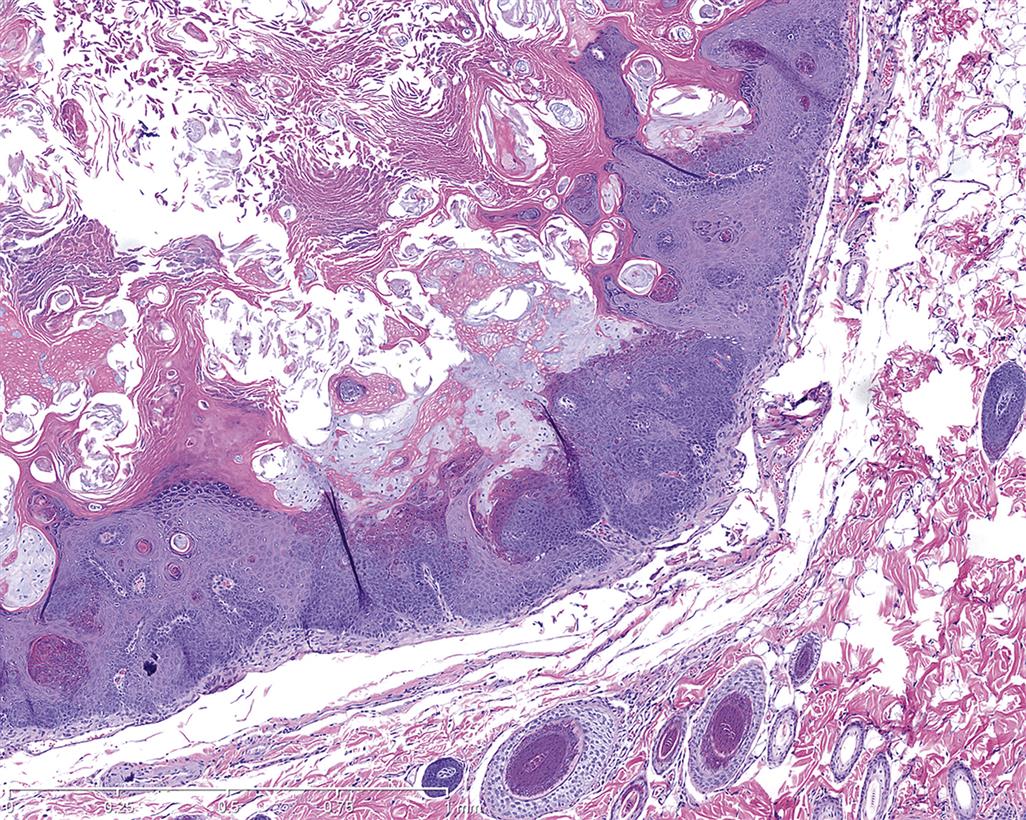

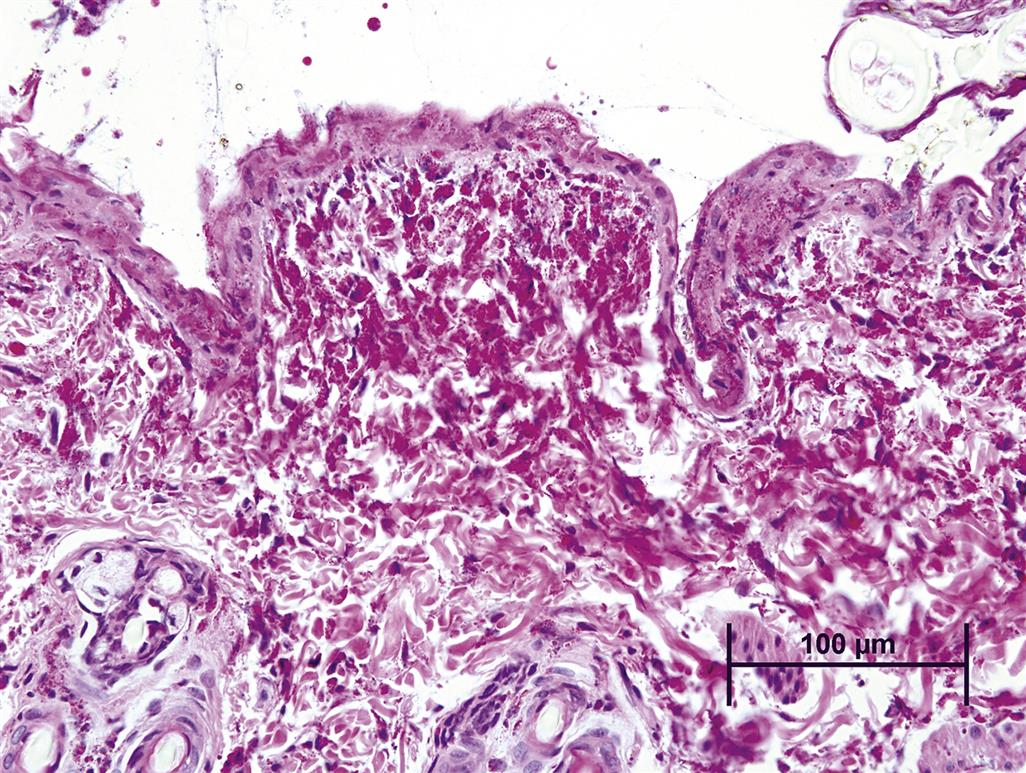

Squamous cell papillomas are benign neoplasms that are derived from epidermal keratinocytes, and are the earliest neoplastic lesion induced by carcinogens in the mouse models of skin carcinogenesis. They can be further characterized into four types: exophytic, endophytic, dysplastic, and nonkeratinizing. The exophytic type has a stalk at its base, and is also often referred to as a pedunculated papilloma. The endophytic type has no stalk, but instead is contiguous with the adjacent epidermis and invaginates to form a depression (Figure 24.11). The dysplastic type contains atypical squamous cells with large hyperchromatic nuclei that are found primarily in the basal and suprabasal layer of the epidermis.

Regardless of type, all papillomas are well-circumscribed papilliform exophytic or endophytic masses with no compression of the surrounding tissue and no capsule. They are composed of keratinizing squamous cells overlying a well-vascularized stroma. Mitotic figures are common. Individual suprabasal cells may show premature keratinization or dyskeratosis, and there is a variable degree of parakeratotic hyperkeratosis.

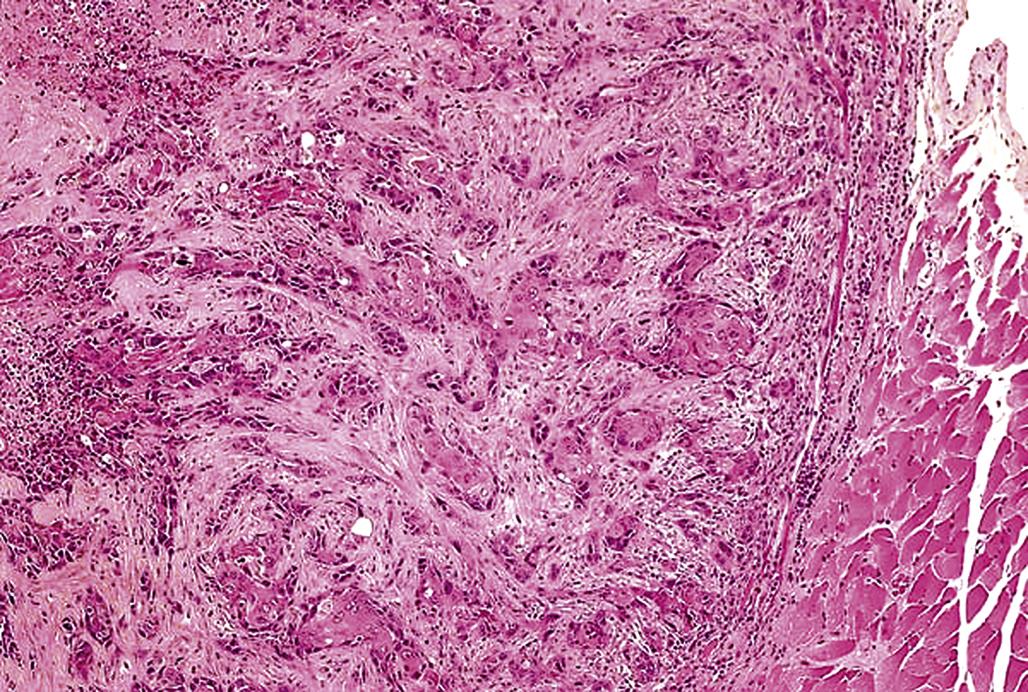

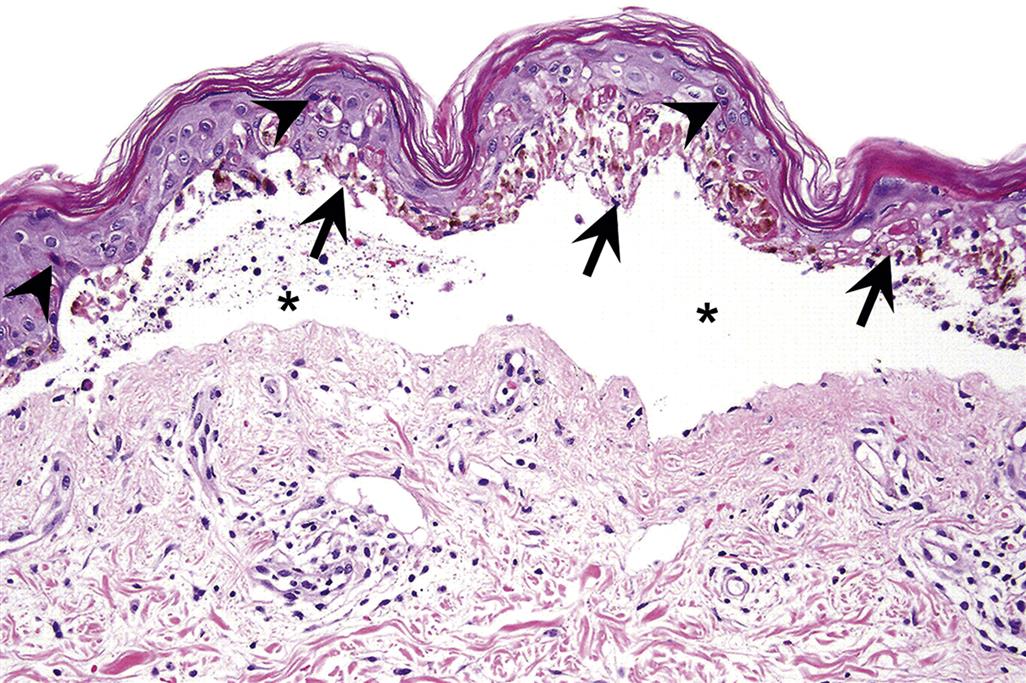

Squamous cell carcinomas, also referred to as epidermoid carcinoma, are malignant neoplasms derived from epidermal keratinocytes. Squamous cell carcinomas are poorly demarcated, generally mostly endophytic, and show no compression of the surrounding mesenchyme, although some tumors elicit a desmoplastic reaction in the surrounding dermis. The tumor is composed of islands or cords of cells that penetrate the basal lamina and invade the dermis, with the neoplastic cells sometimes invading the underlying subcutis or subcutaneous muscle. There is generally some evidence of squamous differentiation (Figure 24.12), although its extent is variable. Centrally located, concentric layers of keratin that are often termed keratin pearls, cancer pearls or horn pearls are also frequently present. Some neoplastic cords may show a central lumen containing individualized (acantholytic) keratinocytes that are surrounded by several layers of neoplastic epithelial cells (pseudo-glandular pattern). Abnormal keratinization (dyskeratosis) of single cells occurs sporadically and intercellular bridges are generally present except in very poorly differentiated tumors.

Benign basal cell tumors are derived from stem cells within hair follicles and/or the interfollicular epidermis and are classified into three distinct types: basosquamous type, trichoblastoma type, and granular type. All basal cell tumors are fairly well circumscribed and multilobulated with some association to the epidermis. The neoplasm is composed of uniform lobules, islands, or cords of closely packed cells that are supported by a variable degree of fibrovascular stroma. Neoplastic basal cells also may be arranged in cords or fine ribbons that may become cystic. There is no invasion of the basement membrane and no compression or desmoplasia of the surrounding dermal mesenchyme. Tumor cells generally resemble normal epidermal basal cells without intercellular bridges, and palisade at the periphery of lobules. Foci of squamous cell differentiation may occur and sebaceous cells may also be present. In the basosquamous type of basal cell tumor, foci of keratinization are present. In the trichoblastoma type, small foci of sebaceous cells and/or follicular differentiation are present. In the granular type, there are basal cells containing periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-positive granules.

Malignant basal cell tumor is also referred to as basal cell carcinoma or basosquamous carcinoma, and is a malignant tumor derived from stem cells within hair follicles and/or the interfollicular epidermis. Malignant basal cell tumors are poorly circumscribed dermal tumors with some association to the epidermis or adnexa and extensive local invasion. They are composed of lobules and cords of closely packed cells that are supported by a variable degree of fibrovascular stroma. Tumor cells generally resemble normal epidermal basal cells without intercellular bridges, and palisade at the periphery of lobules. Central necrosis in tumor lobules may be present; these necrotic areas are referred to as pseudocysts. In pigmented strains, melanin pigmentation is commonly found, desmoplasia in the surrounding mesenchyme is common, and extensive local invasion may be present.

Benign and malignant basal cell tumor development has been very convincingly linked to upregulated hedgehog (Hh) signaling via several lines of evidence, including genetic mutation analyses, mouse models of basal cell tumors, and the successful treatment of malignant basal cell tumors in the clinic using Hh signaling inhibitors. In addition, many if not all basal cell tumors are believed to derive from hair follicle stem cells.

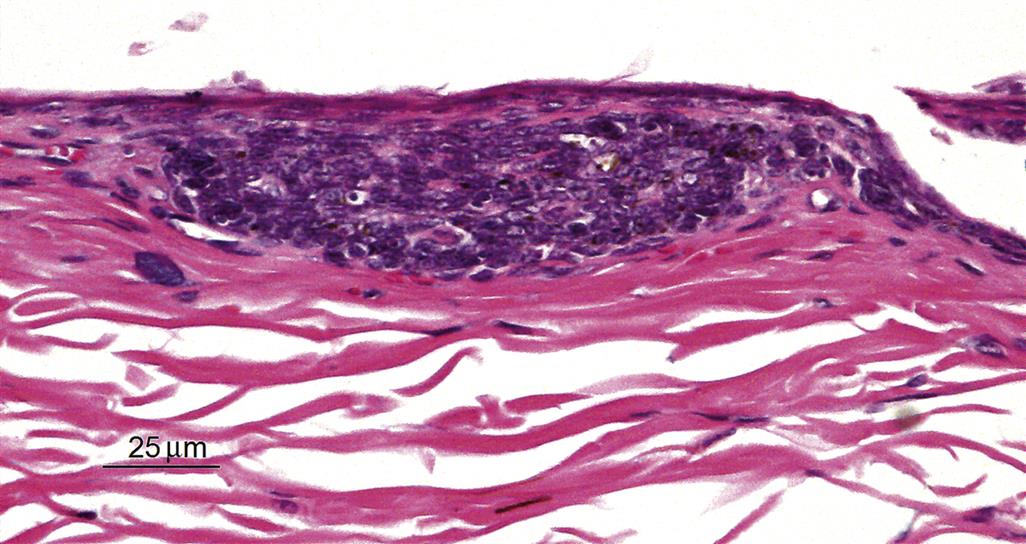

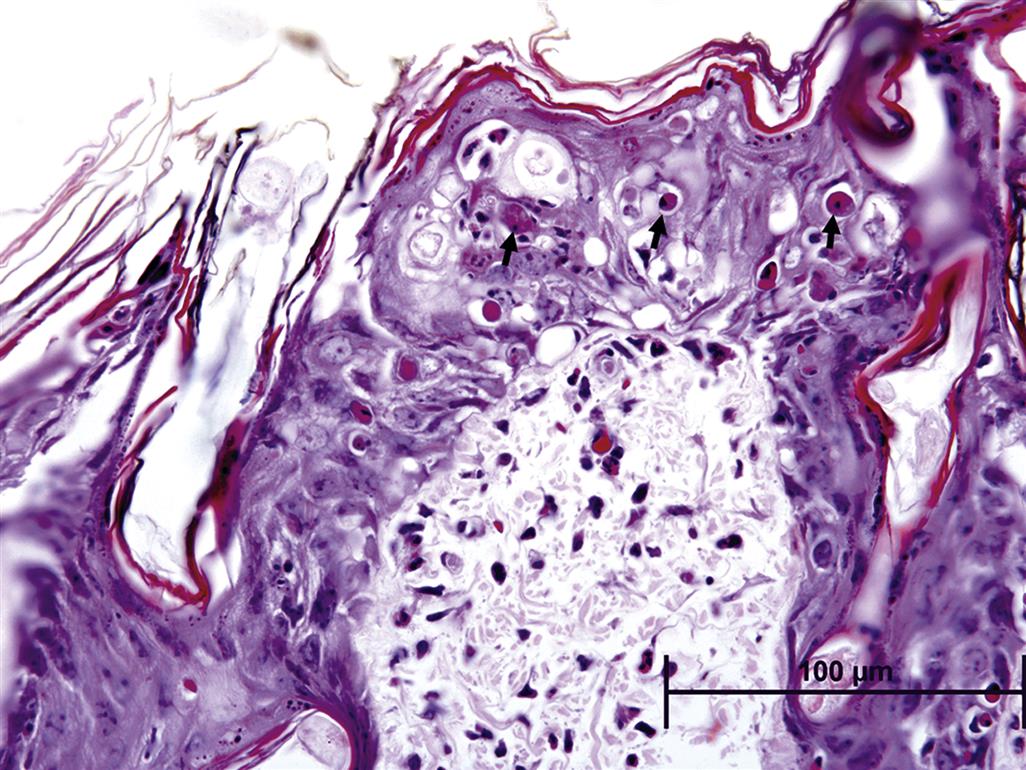

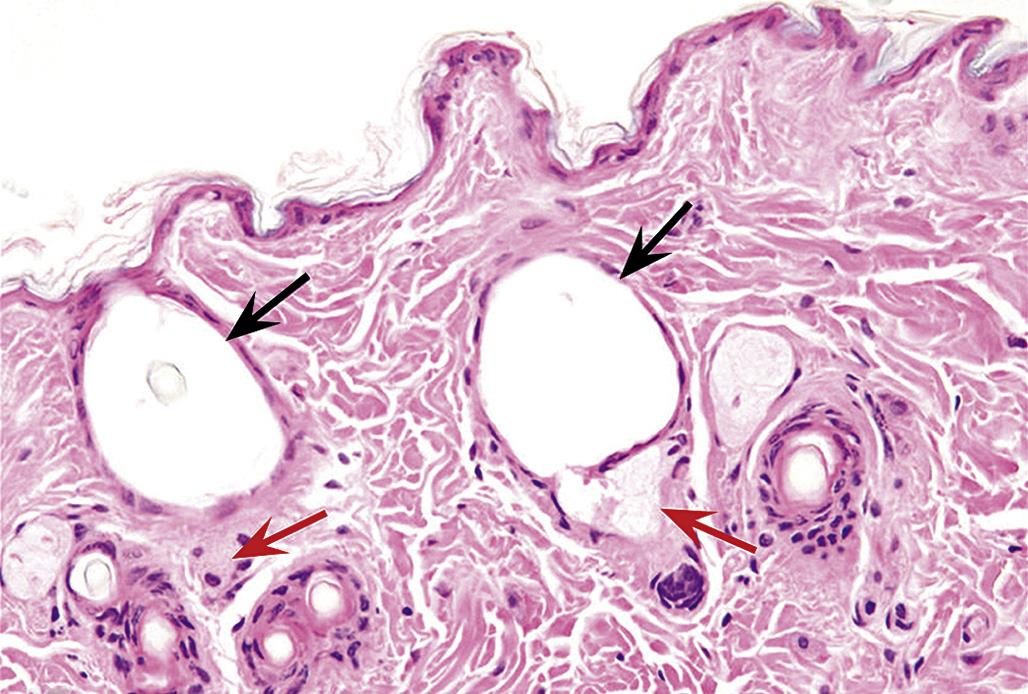

In humans, the vast majority of basal cell tumors have identifiable mutations in at least one allele of patched 1 (PTCH1), a tumor suppressor gene that encodes a Hh signaling receptor. Hh signaling occurs when Hh ligands bind to PTCH1, specifically through SMO, and relieve inhibition of the Hh pathway. This leads to activation of the Gli family of transcription factors and eventually to cellular proliferation. A basal cell tumor from a PTCH1 heterozygous null C57BL/6 mouse is illustrated in Figure 24.13.

Adnexal Neoplastic Lesions

Sebaceous cell adenomas are derived from the reserve cells that line the periphery of gland lobules. In contrast to sebaceous gland hyperplasia, in a sebaceous cell adenoma the normal glandular architecture has become distorted, but the tumor is still composed of lobules and acini and is well demarcated from the surrounding tissue. Squamous differentiation and keratinization may be present and mitoses are often seen at the lobular periphery.

Sebaceous cell carcinomas are less differentiated than adenomas and poorly delineated from surrounding tissue, with frequent deep dermal invasive growth. The tumor is composed of lobules and acini containing polygonal cells of variable size and containing variable amounts of intracytoplasmic lipid vacuoles. There is high mitotic activity with numerous atypical mitotic figures. Squamous differentiation and individual cell necrosis, cystic degeneration with the presence of amorphous cellular debris, and melanin pigmentation may be present. Both sebaceous gland adenomas and carcinomas are rare spontaneous tumors in rodents.

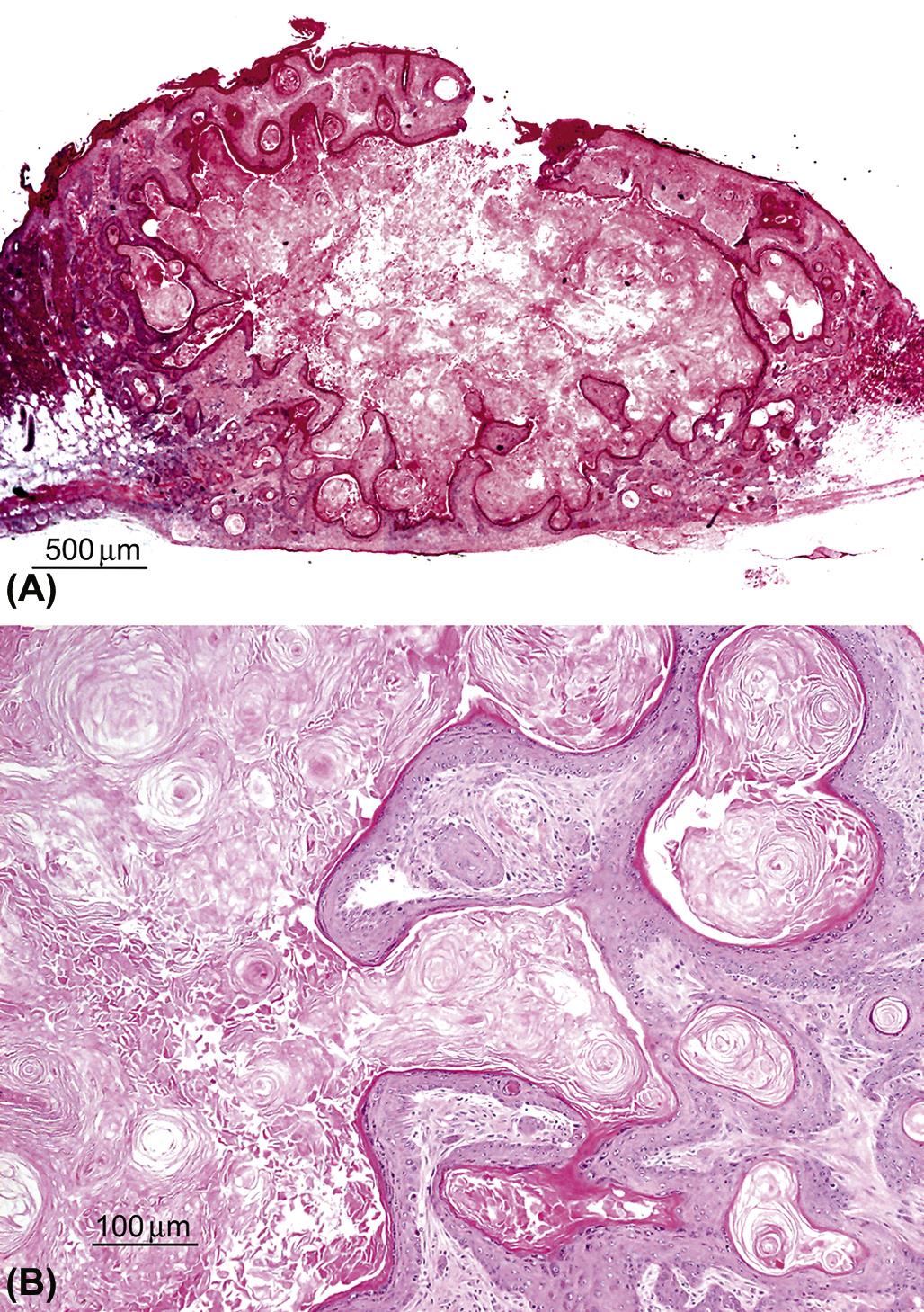

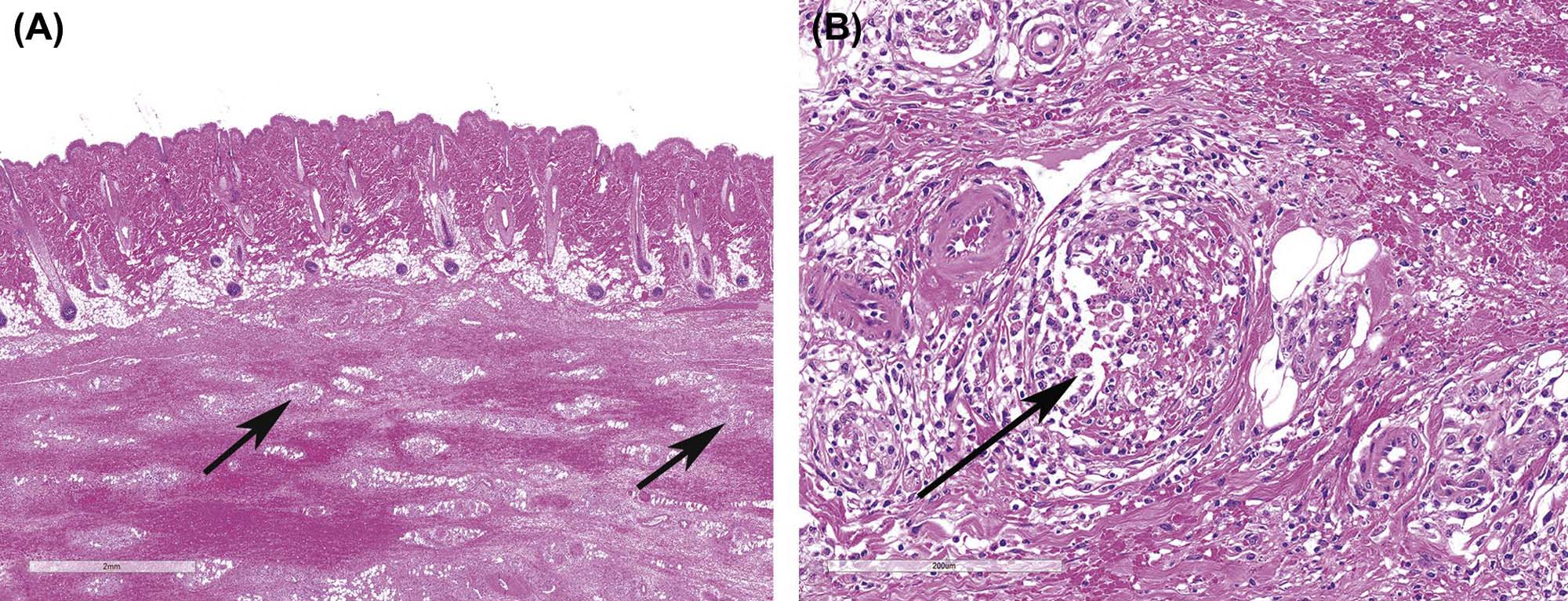

Keratoacanthomas arise from squamous epithelial keratinocytes derived from the infundibulum of the hair follicle. They are very well demarcated but generally unencapsulated masses that occur in the superficial dermis and connect to the overlying epidermis, sometimes containing a pore to the skin’s surface (Figures 24.14A). The tumor is composed of one to several lobules containing a prominent central cavity filled with concentric whorls of keratin. The cavities are lined by well differentiated squamous epithelium that sometimes contains epithelial whorls with central foci of keratinization (Figure 24.14B). Mitotic figures are uncommon. Experimentally induced keratoacanthomas in mice have been reported to undergo spontaneous regression, possibly correlated to the normal hair follicle growth and regression cycle.

Benign hair follicle tumors have four distinct types: trichoepithelioma, trichofolliculoma, pilomatricoma, and tricholemmoma. All four types are derived from the hair follicle matrix, and are all well delineated but unencapsulated with no invasion. All have multiple lobules consisting of different stages of follicular trichogenic differentiation, often with one or multiple cysts.

The trichoepithelioma type is derived from the hair follicle matrix epithelium that gives rise to the inner root sheath and hair shafts. They have a fine mesenchymal matrix that resembles the hair follicle dermal papilla and manifests as focal invaginations of the basement membrane.

In contrast to basal cell neoplasms, the epithelium of trichoepitheliomas does not differentiate into sebaceous cells. The trichofolliculoma type is a large cystic neoplasm that has a large central cystic lumen that contains keratin and hair shafts and which is lined by squamous epithelium. This epithelium gives rise to well differentiated hair follicles that radiate peripherally from the cystic center. The pilomatricoma type consists of multiple nodules of hair matrix and hair cortex epithelial cells that abruptly keratinize without the presence of keratohyalin granules and slough into a central lumen that contains keratin and keratinized ghost or shadow cells (Figure 24.15). The tricholemmoma type is a neoplasm derived from the outer root sheath epithelium and thus consists of small epithelial “nests” lined by a prominent basal membrane. Cells at the periphery of nests are basaloid and palisading while the more differentiated suprabasal cells contain PAS-positive glycogen granules similar to those in the external outer root sheath epithelium of normal anagen hair follicles. Suprabasal cells at the center of the nest often demonstrate tricholemmal keratinization characterized by very hyaline amorphous keratin.

Dermal Neoplastic Lesions

Benign melanoma is derived from epidermal and/or adnexal melanocytes and is characterized by a dense nodular accumulation of pigmented cells within the dermis, with or without an epidermal connection. Neoplastic melanocytes are polygonal, epithelioid, or spindle shaped, with variable degrees of intracytoplasmic melanin pigment granules.

Malignant melanoma is also characterized by a dense nodular accumulation of cells within the dermis with or without an epidermal connection, but there is invasive growth and the neoplastic cells are even more pleomorphic in size and shape, and may or may not contain melanin pigment. When they lack pigmentation, they are referred to as amelanotic malignant melanomas. Both benign and malignant melanomas are very rare spontaneous incidental tumors in rats and mice. Amelanotic melanomas in rats occur most frequently in the pinna, eyelid, scrotum, and perianal region.

Mechanisms of Toxicity

Direct Cutaneous Toxicity

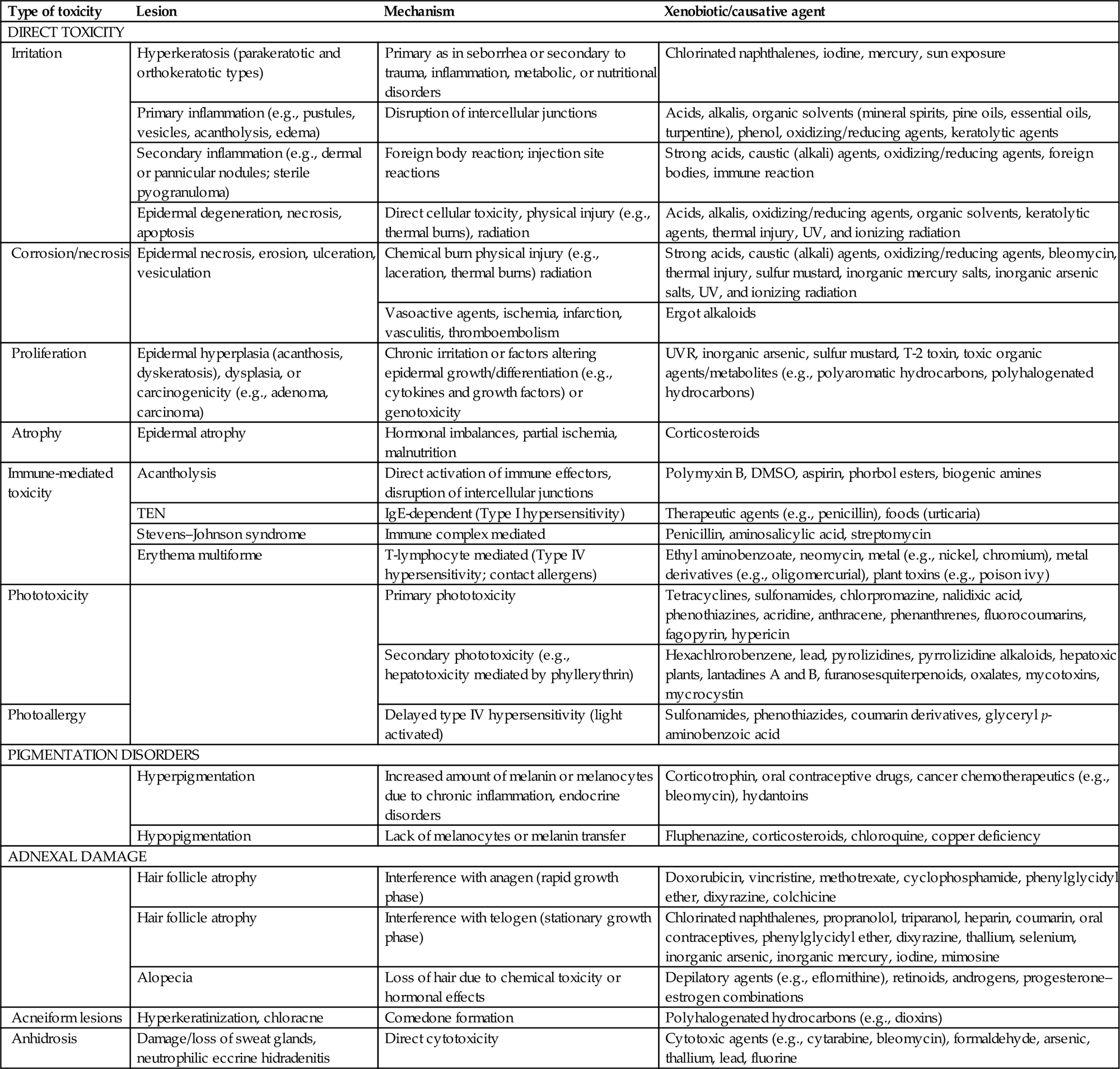

Because of its unique role as a first line barrier defense against a number of environmental insults), the skin is exposed to a wide variety of toxic agents. These toxic agents can harm the skin directly, causing irritation or corrosion, or can induce immune-mediated toxic effects, both systemic and cutaneous, that manifest as cutaneous toxicity (Table 24.5).

Table 24.5

| Type of toxicity | Lesion | Mechanism | Xenobiotic/causative agent |

| DIRECT TOXICITY | |||

| Irritation | Hyperkeratosis (parakeratotic and orthokeratotic types) | Primary as in seborrhea or secondary to trauma, inflammation, metabolic, or nutritional disorders | Chlorinated naphthalenes, iodine, mercury, sun exposure |

| Primary inflammation (e.g., pustules, vesicles, acantholysis, edema) | Disruption of intercellular junctions | Acids, alkalis, organic solvents (mineral spirits, pine oils, essential oils, turpentine), phenol, oxidizing/reducing agents, keratolytic agents | |

| Secondary inflammation (e.g., dermal or pannicular nodules; sterile pyogranuloma) | Foreign body reaction; injection site reactions | Strong acids, caustic (alkali) agents, oxidizing/reducing agents, foreign bodies, immune reaction | |

| Epidermal degeneration, necrosis, apoptosis | Direct cellular toxicity, physical injury (e.g., thermal burns), radiation | Acids, alkalis, oxidizing/reducing agents, organic solvents, keratolytic agents, thermal injury, UV, and ionizing radiation | |

| Corrosion/necrosis | Epidermal necrosis, erosion, ulceration, vesiculation | Chemical burn physical injury (e.g., laceration, thermal burns) radiation | Strong acids, caustic (alkali) agents, oxidizing/reducing agents, bleomycin, thermal injury, sulfur mustard, inorganic mercury salts, inorganic arsenic salts, UV, and ionizing radiation |

| Vasoactive agents, ischemia, infarction, vasculitis, thromboembolism | Ergot alkaloids | ||

| Proliferation | Epidermal hyperplasia (acanthosis, dyskeratosis), dysplasia, or carcinogenicity (e.g., adenoma, carcinoma) | Chronic irritation or factors altering epidermal growth/differentiation (e.g., cytokines and growth factors) or genotoxicity | UVR, inorganic arsenic, sulfur mustard, T-2 toxin, toxic organic agents/metabolites (e.g., polyaromatic hydrocarbons, polyhalogenated hydrocarbons) |

| Atrophy | Epidermal atrophy | Hormonal imbalances, partial ischemia, malnutrition | Corticosteroids |

| Immune-mediated toxicity | Acantholysis | Direct activation of immune effectors, disruption of intercellular junctions | Polymyxin B, DMSO, aspirin, phorbol esters, biogenic amines |

| TEN | IgE-dependent (Type I hypersensitivity) | Therapeutic agents (e.g., penicillin), foods (urticaria) | |

| Stevens–Johnson syndrome | Immune complex mediated | Penicillin, aminosalicylic acid, streptomycin | |

| Erythema multiforme | T-lymphocyte mediated (Type IV hypersensitivity; contact allergens) | Ethyl aminobenzoate, neomycin, metal (e.g., nickel, chromium), metal derivatives (e.g., oligomercurial), plant toxins (e.g., poison ivy) | |

| Phototoxicity | Primary phototoxicity | Tetracyclines, sulfonamides, chlorpromazine, nalidixic acid, phenothiazines, acridine, anthracene, phenanthrenes, fluorocoumarins, fagopyrin, hypericin | |

| Secondary phototoxicity (e.g., hepatotoxicity mediated by phyllerythrin) | Hexachlrorobenzene, lead, pyrolizidines, pyrrolizidine alkaloids, hepatoxic plants, lantadines A and B, furanosesquiterpenoids, oxalates, mycotoxins, mycrocystin | ||

| Photoallergy | Delayed type IV hypersensitivity (light activated) | Sulfonamides, phenothiazides, coumarin derivatives, glyceryl p-aminobenzoic acid | |

| PIGMENTATION DISORDERS | |||

| Hyperpigmentation | Increased amount of melanin or melanocytes due to chronic inflammation, endocrine disorders | Corticotrophin, oral contraceptive drugs, cancer chemotherapeutics (e.g., bleomycin), hydantoins | |

| Hypopigmentation | Lack of melanocytes or melanin transfer | Fluphenazine, corticosteroids, chloroquine, copper deficiency | |

| ADNEXAL DAMAGE | |||

| Hair follicle atrophy | Interference with anagen (rapid growth phase) | Doxorubicin, vincristine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, phenylglycidyl ether, dixyrazine, colchicine | |

| Hair follicle atrophy | Interference with telogen (stationary growth phase) | Chlorinated naphthalenes, propranolol, triparanol, heparin, coumarin, oral contraceptives, phenylglycidyl ether, dixyrazine, thallium, selenium, inorganic arsenic, inorganic mercury, iodine, mimosine | |

| Alopecia | Loss of hair due to chemical toxicity or hormonal effects | Depilatory agents (e.g., eflornithine), retinoids, androgens, progesterone–estrogen combinations | |

| Acneiform lesions | Hyperkeratinization, chloracne | Comedone formation | Polyhalogenated hydrocarbons (e.g., dioxins) |

| Anhidrosis | Damage/loss of sweat glands, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis | Direct cytotoxicity | Cytotoxic agents (e.g., cytarabine, bleomycin), formaldehyde, arsenic, thallium, lead, fluorine |

From Haschek, W.M., Rousseaux, C.G., Wallig, M.A. (Eds.), 2013. Haschek and Rousseaux’s Handbook of Toxicologic Pathology, third ed. Academic Press (Elsevier), San Diego, CA, Table 55.5, pp. 2254–2255, with permission.

Direct cutaneous toxicity is caused by direct damage to the skin by any number of external irritants, such as chemical agents, xenobiotics, infectious agents, thermal injury, or UVR that damage or disrupt the skin’s barrier function. When this occurs, the skin mounts an inflammatory and proliferative response in order to prevent further damage and to restore a morphologically and physiologically functioning barrier.

Direct cutaneous toxicity activates the innate, but not the adaptive, immune response. For example, reversible damage to the skin by direct contact with toxic agents is referred to as irritation, and results in activation of mast cells, complement, and/or prostaglandin synthesis. Irritation generally occurs within 4 hours following topical application of the irritating substance. Histopathologically, skin irritation is characterized by epidermal hyperkeratosis and hyperplasia with dermal inflammation, and is frequently associated with a variety of other epidermal changes such as erosion/ulceration, necrosis, or vesicular change.

When the skin damage induced by direct contact with the initiating agent is irreversible, the lesion is referred to as corrosion. Corrosion is characterized by full-thickness necrosis of the epidermis, leading to ulceration with penetration into the underlying dermis and involvement of the cutaneous adnexa and even the underlying subcutaneous tissue.

When chemical substances or xenobiotics are applied directly to the skin, their effect is determined not only by their primary mode of toxicity but also by the processes of cutaneous absorption and metabolism of the substance. The outer surface of the skin is coated by the lipid sebum, which is secreted from the sebaceous glands and forms a barrier to polar water soluble compounds.

A specific example of direct cutaneous toxicity is direct thermal injury, also referred to as a burn. Burns have classically been classified into three categories: first-, second-, and third-degree burns. First-degree burns have lesions that are limited to the epidermis, and resemble those induced by slight UV irradiation, with the formation of individually necrotic epidermal keratinocytes, or “sunburn cells.” First-degree burns are often accompanied by mild dermal erythema and edema.

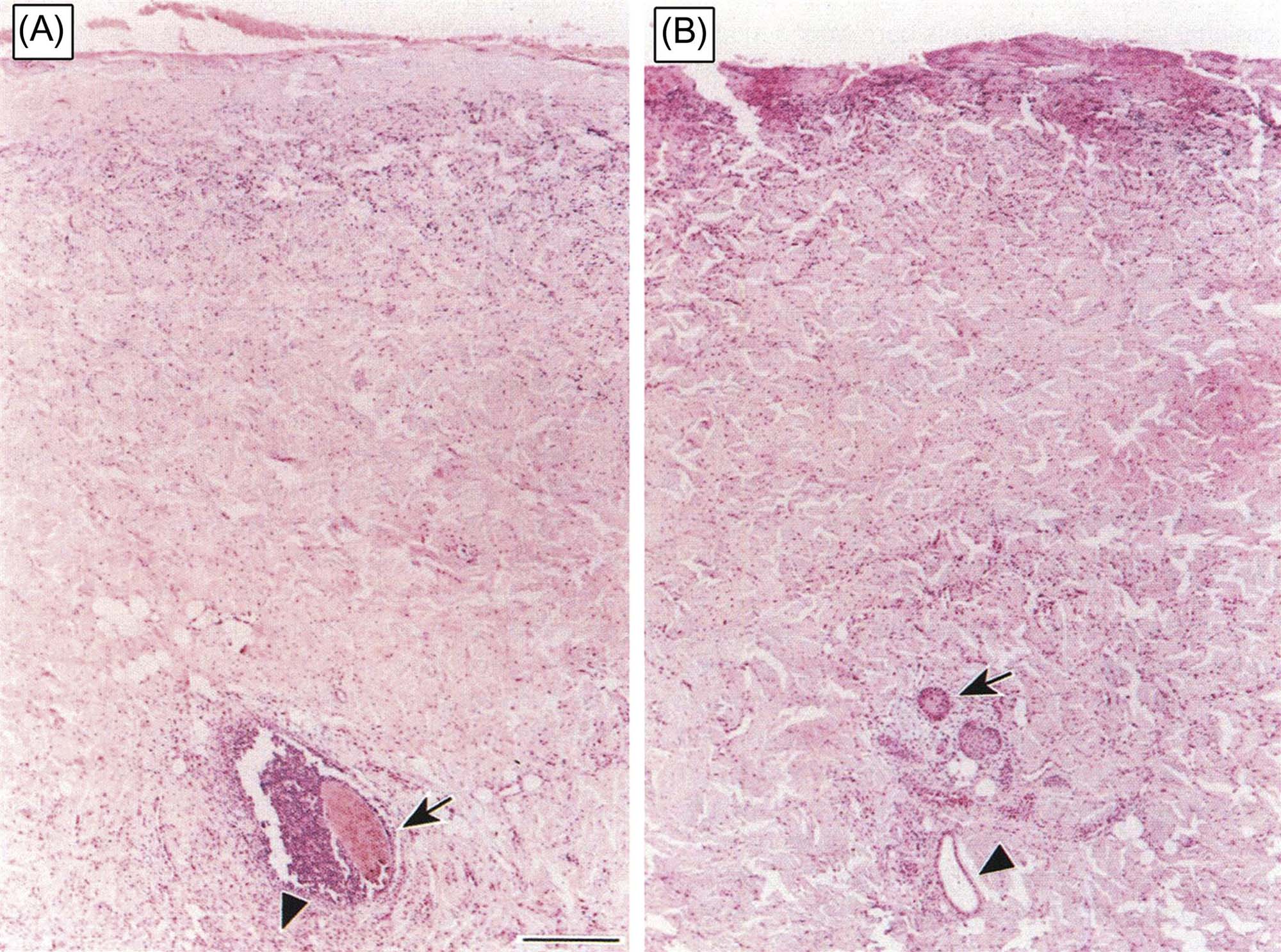

Second-degree burns epidermal necrosis with epidermal–dermal separation leading to cleft formation, but again with only mild dermal lesions of erythema, edema, and sometimes mild leukocytic infiltration. Third-degree burns are characterized by both epidermal and dermal necrosis. While these classic descriptions are still in common usage, clinical practice and experimental studies frequently use the alternative classification of full- and partial-thickness burns.

Partial-thickness burns are further classified as superficial, which are roughly equivalent to first-and mild second-degree burns, and deep, which are roughly equivalent to severe second-degree burns or less severe third-degree burns. Deep partial-thickness burns are characterized by full-thickness epidermal necrosis with necrosis of superficial cutaneous adnexa and dermal vessels but sparing of deep cutaneous adnexa and vessels. They can be distinguished from full-thickness burns, which exhibit complete epidermal and dermal necrosis, including necrosis of all cutaneous adnexa and dermal vessels, by staining for the presence of proliferation markers (e.g., PCNA), which will be present in partial but not full-thickness burns (Figure 24.16). One can also stain for intact collagen with stains such as Masson’s trichrome, which will demonstrate the depth to which dermal collagen fibers have undergone coagulation.

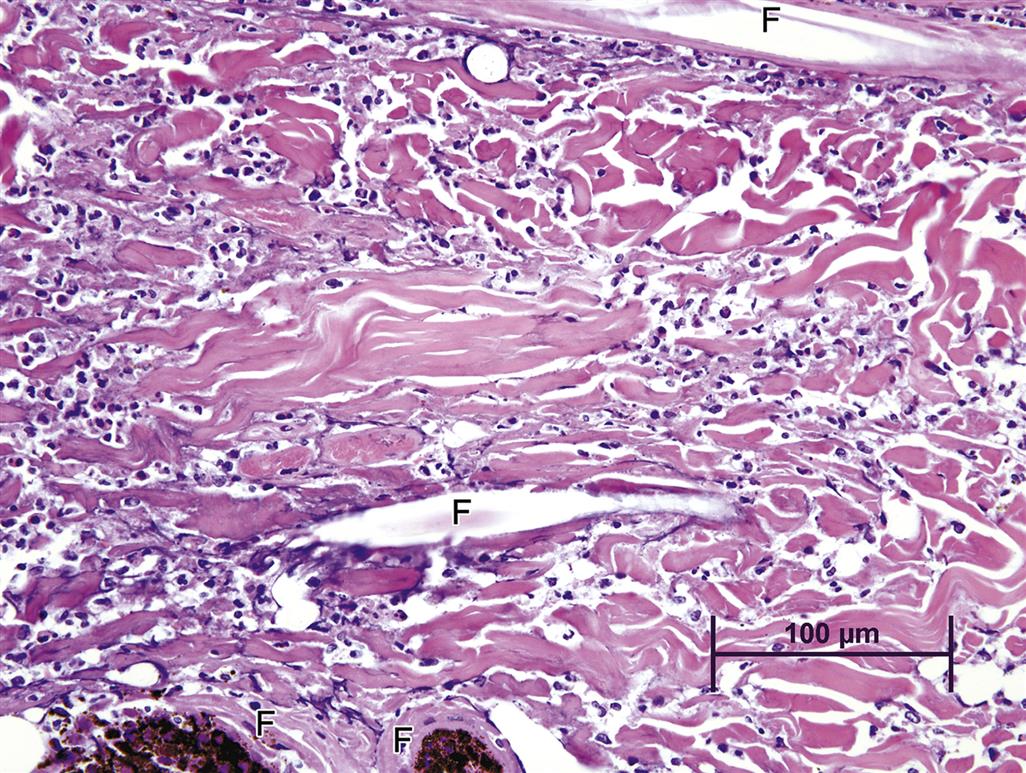

Mild thermal injury is histologically characterized by nuclear and cytoplasmic swelling, generally of epidermal keratinocytes in superficial burns, with later development of individual necrotic keratinocytes. More severe thermal injury is characterized by nuclear rupture, pyknosis, and necrosis of epidermal keratinocytes that exhibit brightly eosinophilic cytoplasm that cannot be morphologically distinguished from premature keratinization, or dyskeratosis. With severe thermal injury, the entire epidermis may undergo necrosis with subepidermal vesicle formation and separation from the underlying dermis (Figure 24.17). Following initial severe thermal damage to the epidermis, adnexa, and dermis, a marked inflammatory reaction generally follows, characterized initially by an infiltration of neutrophils (Figure 24.18), followed subsequently by mononuclear inflammatory cells, including macrophages and lymphocytes.

Another example of direct toxic injury is that induced by the T-2 trichothecene mycotoxin, produced by any one of a number of different fungi of the genus Fusarium. T-2 toxicity manifests as degeneration and necrosis of epidermal basal cell layer keratinocytes with progression to full-thickness epidermal necrosis and ulceration. Necrosis of the dermis is also frequently seen (Figure 24.19). The specific mechanism of T-2 toxicity is unknown, although recent studies suggest that the toxin may cause direct damage to cell membranes, with little or no effect on DNA.

A special example of direct cutaneous toxicity is genotoxic injury due to interaction of the toxic agent with DNA, particularly in epidermal keratinocytes, since these cells exhibit a high rate of proliferation and turnover. The initial damage caused by genotoxic agents occurs in the basal layer of the epidermis, where the toxic agent can interact with DNA by a variety of mechanisms such as alkylation, DNA strand breaks, chromosomal breaks, and adduct formation. This results in an increased rate of mutation. At lower doses the only obvious effect may be the induction of neoplasia. At higher doses the probability of lethal mutation increases, and regenerative epidermal hyperplasia is observed when surviving keratinocytes proliferate in order to replace the cells lost by necrosis due to damage by the mutagen.

In extreme cases, the action of the mutagen impairs the cell renewal process itself, resulting in ulceration since replacement of cells lost to differentiation, as well as replacement of damaged cells, is not possible. This mechanism of toxicity is thought to be the cause of the necrotizing lesions associated with sulfur mustard (mustard gas), which selectively targets basal keratinocytes, causing extensive alkylation of DNA to the point of cell death, leading to necrosis of individual epidermal keratinocytes and epidermal vesicular change, often accompanied by a secondary dermal inflammatory response (Figure 24.20).

Immune-Mediated Cutaneous Toxicity