Elephants are wonderful animals, aren’t they? Giant, lumbering, gentle creatures, they are loving parents to their young, kind and nurturing with a true sense of community. They also have some unique qualities. For example, they can’t run. When they go on a rampage, the most they can do is walk very fast. And, they can’t turn their heads, because they have no necks! To turn to look at something, they must move their entire bodies, which is cumbersome. But, that puts them at no disadvantage. They’re never in a rush to move, because they have no natural predators—except, of course, men without a conscience and an appetite for ivory.

Perhaps the most wonderful things about elephants are the unexpected details, which we’ll uncover in this chapter. So, throw away all your preconceived ideas about elephants, because those can get you into trouble. Get ready to learn the elephant characteristics that might be at odds with what you thought you knew. You’re in for a pleasant surprise.

There are two types of elephants: African and Asian (sometimes referred to as Indian). Before we get to the details, let’s compare the two. The African elephant is, by far, the more popular elephant with artists. It is the larger of the two types, making it more awesome and powerful looking. However, the Asian or Indian elephant can seem more people-friendly. Many charming illustrated children’s books feature human characters who befriend elephants (and vice versa), and they, by and large, are Asian or Indian elephants. Compare these drawings to get a feel for all the differences between the two.

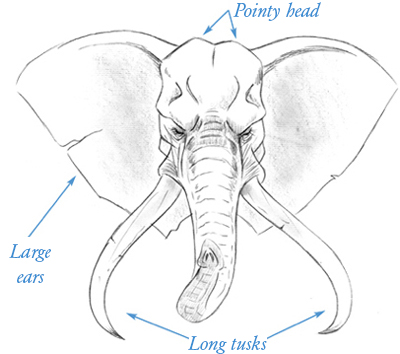

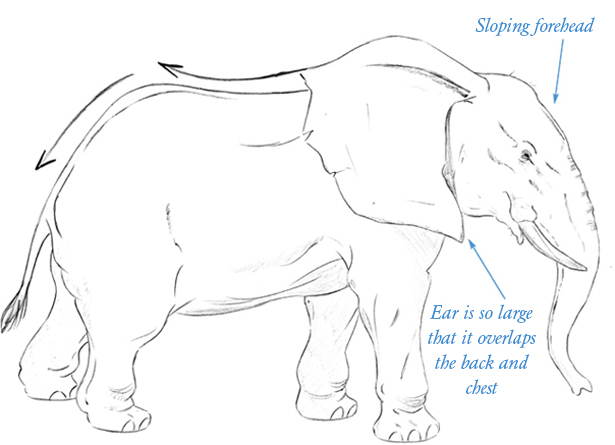

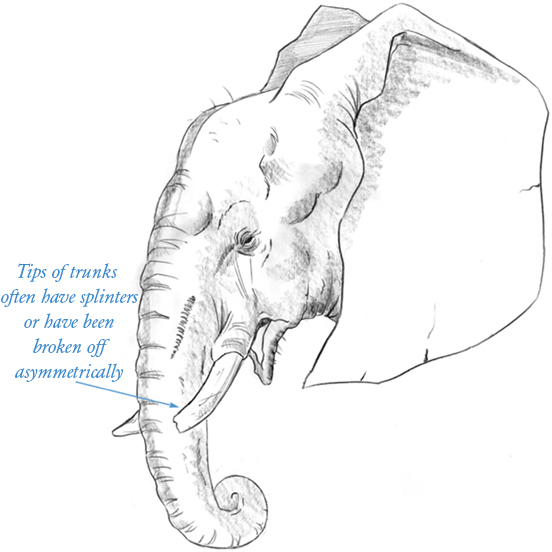

In the profile, the top of the head tapers more on the African elephant than it does on the Asian variety. It comes to more of a point. The ears are huge, with a very wide span. The tusks are impressive, reminiscent of the wooly mammoth.

The African elephant has a more complex back arch than the Asian elephant. On the African elephant, the arch actually changes direction. The African elephant is also significantly bigger and more massive than its Asian counterpart.

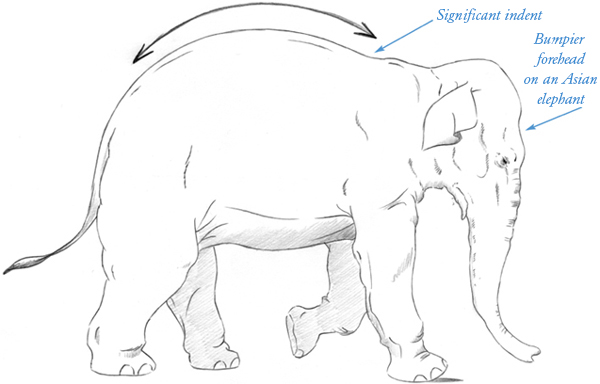

The Asian elephant has two rounded bumps at the top of its head. The ears are smaller and floppier, and the tusks are less threatening. Also note the subtle difference around the brow area. The brow is not thick and heavy, leaving the eyes more open—giving a slightly friendlier look.

The back arch is one, simple convex curve. The forehead is more pronounced here than on the African variety.

Now, on to drawing elephants. Let’s start with the side view of an African elephant, as it give us the clearest view of the trunk and a chance to draw those incredible ears. In this angle, you can see clearly how the trunk originates from the top of the forehead. The other benefit of this pose is that the trunk doesn’t hide the mouth, as it does in the front view. And, you can see the exact spot at which the ear attaches to the head.

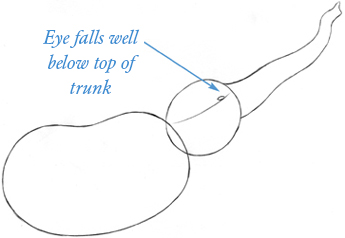

The first thing that might catch you a little off guard is how incredibly tiny the elephant eye is. Place it on the eyeline slightly below the center of the head.

The eye is encircled by a series of concentric wrinkles. The mouth curves away from the face in a rubbery way because there is a very little chin.

Be sure to draw the pronounced cheekbone contour line.

There is a minor split bump at the top of the head and a bump over the trunk in the African elephant. The Asian elephant has a more pronounced bump.

There’s a pronounced facial contour line that stretches from the tear duct to the origin of the tusk, indicated in the drawing by an arrow. There’s also a series of compressed, accordion-like wrinkles behind the lower lip and chin. The ears on the African elephant are gigantic, wrapping around the head and even below it.

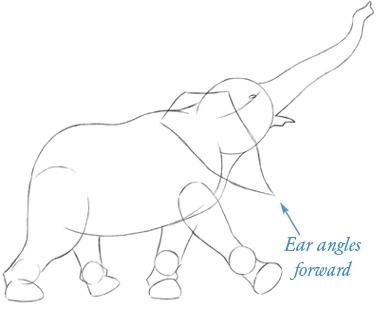

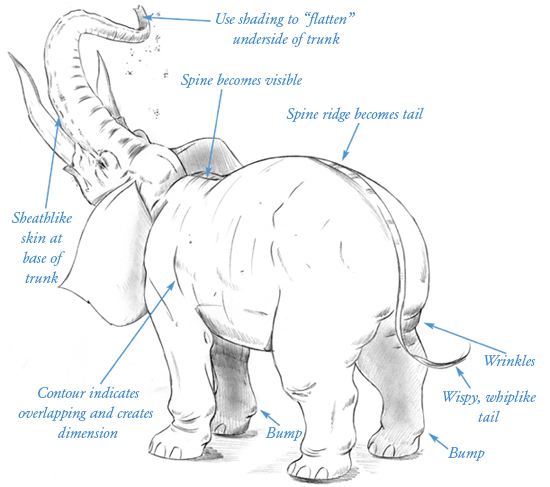

This is a good pose from which to view the compete outline of the elephant. Note that, due to the stretching posture with the head held high, the torso takes on a kidney-bean shape.

Notice how the head overlaps the body, because there’s no neck to connect them. The trunk itself is a long muscle. Without any bones in it, it can’t be held perfectly straight like a human arm. So, when the elephant extends its trunk up and out, the trunk curves and bends—even at its straightest.

Note how the muscle and fat on the chest hangs due to the effects of gravity.

Since this is an African elephant, the ears are substantial.

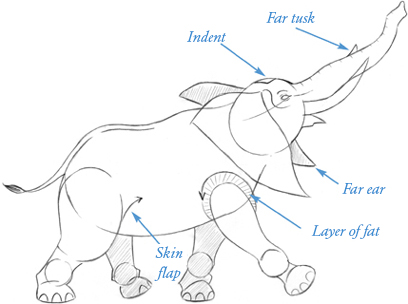

The ridge of the spine shows all the way down the back to the tail. Layers of fat and skin flaps encircle the tops of the legs. And, don’t forget the details on the far side of the body; a bit of the far ear and the far tusk should be visible.

When the elephant’s foreleg is extended in front and the hind leg is all the way back, draw a good amount of stretch lines on the underside of the belly, where the loose skin is pulled tighter.

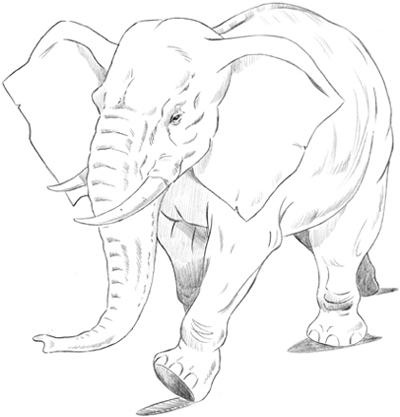

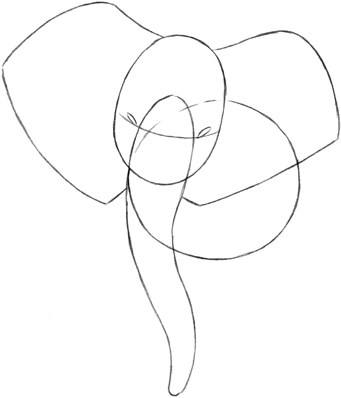

The front view is a dramatic angle from which to draw the elephant. We don’t often think of elephants this way, but it’s effective to portray this giant creature coming right at you. This example shows the Asian elephant.

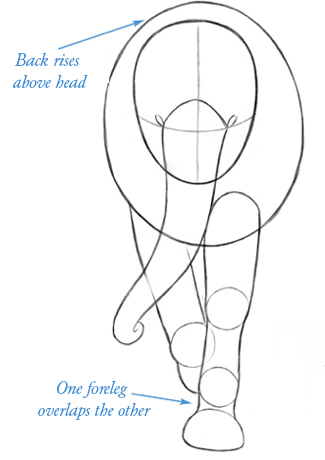

Note that the back rises above the head. Also, the foreleg that steps out in the front overlaps the other foreleg. This brings us to another secret of drawing elephants: They have very long, thin legs, epecially at this angle. Moreover, the rear legs are all but hidden from view. As the elephant walks, there is a slight sway from side to side. The trunk lags behind a beat, swaying in the opposite direction of the body’s momentum.

An Asian elephant’s eyes appear to look up at the viewer whereas an African elephant’s eyes look from an angle.

If you were drawing the African elephant, the ears would be very dramatic in this angle, like the outstretched wings of an eagle. Since this is the Asian elephant, however, the ears are smaller.

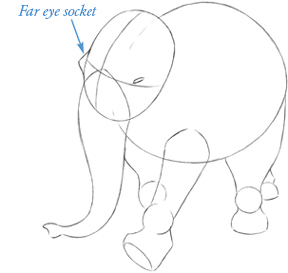

The key to drawing an elephant’s frame in any view is simplicity. Keep it bold and simple.

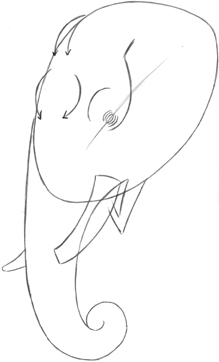

The head is an elongated oval in the 3/4 view. Don’t forget to omit any sign of a neck connecting the head to the body. Even though elephants have long legs, the joints are big and round, which make them stand out in the outline. In order to sustain such immense weight, their feet are wide pads, like giant cushions.

Lots of overlapping on a large scale does the trick in this step. The head, body, trunk, and legs are all composed of overlapping lines.

The arrows indicate where the shading and contouring on the torso should go. The line that creates the cheekbone sweeps up to become the top of the sheath that holds the tusk, which grows directly out of the skull in front of the mouth and teeth.

Elephants love to throw their heads back and let some dirt fly. I suppose it’s their idea of “freshening up.” As long as it works for them, who am I to argue? Like the following example, this is also a 3/4 view—just from the other end. Regardless of direction, the 3/4 view adds depth and interest to a drawing. Even though the effects of perspective are only slight here, some foreshortening is required. Due to the angle, the back end of the animal is like a hill, partially cutting off most of the “valley” of the back from view. You lose sight of the spine temporarily, until it reappears near the shoulders. Some overlapping of the sections of the body occurs, which makes the torso look more three-dimensional than it otherwise would.

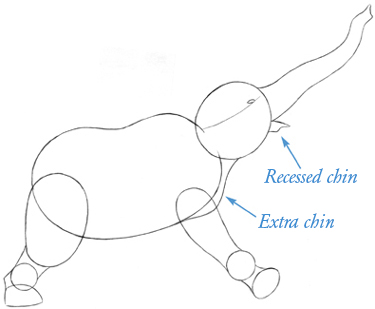

Name me one person who doesn’t have a soft spot for baby elephants. What is it that makes them so cute? Big eyes? No, they have tiny eyes. Short, chubby legs? Nope, their legs are long in proportion to their body size. You’re thinking about the proportions of a puppy or a bear cub. Let’s find out what makes a baby elephant such a cutie. It has a large head, compared to the body size, and its ears, legs, and trunk are too big, since it hasn’t grown into its adult proportions yet. It also has a confused, unassuming expression.

The body is compact and almost circular, rather than elongated.

As a youngster, it doesn’t have the intimidating scowl of an adult yet.

The legs are long and thin, but they are close together since the baby elephant’s stance is unsteady. (Wide stances are sturdy.)

The legs curve in slightly for that wobbly look.