XXII

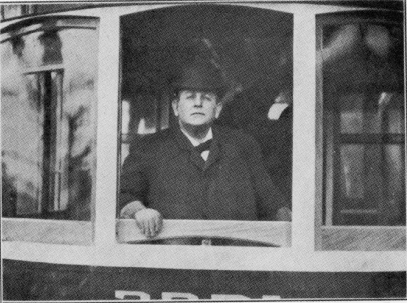

FIRST THREE-CENT FARE CAR

TWELVE or fourteen miles of track on the west side, overhead construction and power-houses had been completed and everything was in readiness for operating the line from Denison avenue to the point of contention already referred to — the six hundred feet on Detroit avenue from the intersection of Fulton road to the viaduct.

Sixteen months before this Judge Robert W. Tayler of the United States Court of the northern district of Ohio had held that the Concon’s franchise on Central and Quincy avenues had expired on March 22, 1905. Council had therefore granted the Forest City Company the right to operate on these two routes, and while the city could have stopped the operation of the Concon cars it permitted them to continue without interference. We thought it better to permit the service at the higher fare than to deprive the car-riders of it. Now, however, when the low fare lines got ready to connect with Central avenue, which extends eastward from the Square and which was reached by free territory tracks in the down town portion of the city, more injunctions were forthcoming. Workmen were promptly prevented from tearing up Brownell, now Fourteenth street, preparatory to laying the tracks for the connection, and at about the same time, John W. Warrington of Cincinnati, applied to the supreme court of the United States to prevent the city of Cleveland from interfering with the Cleveland Electric Street Railway Company’s operations on Central and Quincy avenues and Erie street. Warrington was accredited with being one of the chief influences in having secured from the supreme court of Ohio a reversal of that court’s decision in the case of the Rogers law. Under this law the Cincinnati Traction Company held a fifty-year franchise on all the street railways in Cincinnati. The supreme court declared the law unconstitutional. Then Warrington and his associates took it up and secured a reversal of this decision. He was said to have been one of the principal movers also in the framing of the municipal code, so our city’s affairs were not wholly unfamiliar to him.

While all this was transpiring in the last days of October the cars of the Forest City Railway Company were on their way from the factory in the east to Cleveland, and on November 1, 1906, the first three-cent-fare car made its first trip from Denison avenue to Detroit avenue over the unenjoined part of the road. By common consent I was the motorman. City officials and other friends of the municipal ownership movement were the passengers on that initial run, but the company rules were enforced and every passenger paid his fare. It was just five years and six months to a day since I had been elected mayor the first time, and at last part of our dream had come true — not that I had ever doubted that it would! but it was good to feel that we had really gotten somewhere finally.

It was a sunshiny day and the brightness of the day seemed to be reflected in the faces of the men, women and children who crowded around us at the car-barns and lined the streets all along the route. They had even decorated their houses, some of them, with flags and bunting as if it were a holiday, and here and there women on the streets threw bunches of fall flowers from their own little gardens towards the big new yellow car as it passed. A committee of women, I remember, brought a big floral piece to me at the car-house and said they wanted to thank us for getting the three-cent fare for them. That was the best of it — it was a people’s victory — a victory for women and children as well as for men, and they all knew it. I don’t know, of course, but I think I was the happiest person in the whole crowd, and I guess I looked it, for one of the newspapers said that my smile expanded and broadened until it eclipsed everything behind it in the three-cent car.

“By common consent I was the motorman.”

Photo by L. Van Oeyen

First three-cent tare car—November 1, 1906

With the operation of the first three-cent-fare car the stock of the Cleveland Electric Railway Company went down to sixty-three.

I confidently believed that the injunction on Detroit avenue would be dissolved in a few days and that the low-fare cars would run over into the center of the city without further obstruction, but I was too hopeful. Shortly after the line was put into operation I went out of town on business, to Chicago if I remember rightly, as that city was in the midst of its traction war then and Mayor Dunne and I exchanged several visits. When I got back Mr. du Pont, president and operating manager of the Municipal Traction Company, met me at the station with the somewhat disheartening news that the injunction still held, but immediately followed it up with the startling suggestion to “jump the viaduct.” We had been in a good many tight places together in the course of street railway operations in other cities and we agreed that physically this feat could be accomplished, but whether it could be done legally neither of us knew. After nearly a whole day’s conference with his lawyers they gave their sanction to Mr. du Pont’s plan, I believe because they saw he was going to do it anyway. The next day, under his personal direction, in the midst of an interested crowd in which the Concon attorneys figured conspicuously, a Forest City car was derailed at “injunction point,” as Secretary Colver humorously dubbed the place where the low-fare cars were forced to stop. By the use of horses, jacks, a gang of men and the municipal’s own current (for du Pont was careful not to use any of the Cleveland Electric’s power), the car was pushed, bumped, lifted, carried along somehow, and at last safely landed on the tracks on the viaduct and others soon followed.

It will be remembered that I said in the beginning of this story that it was the city’s ownership of those tracks on the viaduct that gave the community its chief strength in the struggle to come years later. Low-fare cars were on those tracks now where they couldn’t be enjoined. That ancient expedient — a free bus — was at hand to transfer passengers from the terminal of the Forest City’s right of way on Detroit avenue to the waiting cars at the west end of the viaduct, but it wasn’t really needed. The passengers were more than willing to walk that six hundred feet.

From 2:30 p. m. until midnight the cars were operated over the viaduct at intervals of five or six minutes. A switch had been put in on the west approach of the bridge where the cars could be stored when not in use. Within a few days the three-cent cars would have been operating to the Public Square, but the day after they were gotten onto the viaduct the Threefer was met with the most outrageously unjust injunction which it had so far encountered, and that is putting it pretty strongly. The restraining order affecting the strip on Detroit avenue which had just been jumped was now made to include territory on Superior street between the east end of the viaduct and the Public Square. This portion of Superior street had been free territory since 1850. A free territory clause was contained in the first franchise ever granted by the city, the question had twice been fought out in the supreme court and both times that body had declared the territory free. For any man or set of men to claim the exclusive right to this portion of street was certainly the height of arrogant disregard of the city’s right to control its own streets. But be that as it may, the low-fare cars were now stopped at the east terminal of the viaduct. At one of the hearings one of the Concon’s eminent attorneys made those present gasp for breath when he gave voice to the remarkable statement that, “if the right which we claim is well founded, it is our contention that no one has the right to interfere with us in the operation of cars even to the extent of running a ’bus line.”

The court granted the restraining order on the ground “that the ordinance of the city council fixing the compensation for the joint use of the tracks by the defendants was invalid because of the admitted financial interest of Mayor Johnson in the defendant company.” This decision came just at Christmas time in 1906.

The night of December 26 the Forest City Company attempted to lay temporary tracks on top of the pavement on Superior street, N. W. If it had succeeded the three-cent cars would have been running to the Square by seven o’clock the next morning. The low-fare people believed the Concon could not enjoin them from laying these tracks, but at three o’clock in the morning an injunction was served at the instigation of a property owner, who was also a Concon stockholder. There was nothing to do but to stop the work. A day or two later, by permission of the court, the Forest City people removed their wagons, tools and equipment from the street awaiting the action of the court on the temporary restraining order. On January 2, 1907, Judge Beacom ruled that the Forest City Company had no right to construct separate tracks on Superior avenue. The company promised to remove its temporary tracks immediately and at once put that promise into execution. On that same day Judge Ford issued injunction No. 32 against the Low Fare Company stopping the laying of tracks at Sumner avenue, S. E. The Low Fare Company had a franchise from the council for tracks on Sumner avenue and on New Year’s day had put a force of one hundred laborers to work at laying tracks on Sumner avenue from East Fourteenth to East Ninth streets. The company already had tracks on these streets which it wished to connect by the Sumner avenue route. Six hundred feet of track had been laid when the work was stopped by Judge Ford’s injunction, January 2. This is the way the holiday season was being celebrated by the contending forces in Cleveland.

But the people were getting the benefit of the contest, for on December 31, 1906, the Concon commenced to sell seven tickets for twenty-five cents. It was now fighting desperately to have all the low-fare grants declared void on the ground that I was financially interested in them. All of the facts as to this contention have already been related and the utter absurdity of the charge shown. It isn’t worth while to follow the legal intricacies of the thing; and it is anything but pleasant to recall the methods employed to poison the minds of the people, but if one purpose of the story of our nine years’ war with privilege in Cleveland is to arm other fighters in other fields with courage to resist and to endure, it would be less than fair, perhaps, to say nothing on this subject. Under the heading Street Railway Talks the Cleveland Electric Street Railway Company was running daily double column reading matter in several newspapers purporting to be educational propaganda on the local situation. No. 120 of the “talks” appeared November 24, 1906, under the usual note, reading:

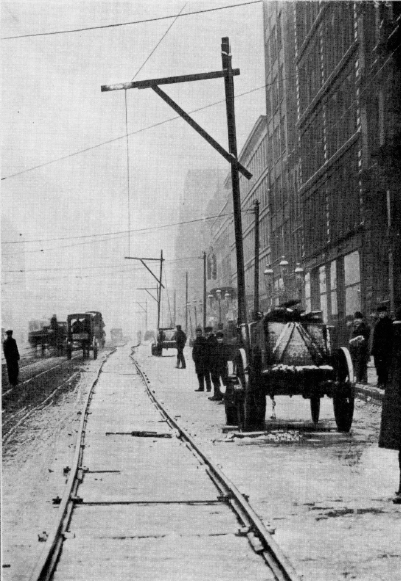

Photo by L. Van Oeyen

“The night of December 26, 1906, the Forest City Company attempted to lay temporary tracks on top of the pavement on Superior St., N.W.”

“NOTE — Each day you will hear something new on the street railway situation. Read it, and if you disagree or care to make any suggestions concerning it, we shall be glad to hear from you.”

“THE CLEVELAND ELECTRIC RAILWAY COMPANY,

“By Horace E. Andrews, President.”

This is what talk No. 120 said:

STREET RAILWAY TALKS.

No. 120.

THE CHICAGO NEWSPAPERS are giving some attention to the Cleveland branch of the TOM L. JOHNSON STREET RAILWAY TRUST.

THIS IS THE WAY IT LOOKS to the CHICAGO JOURNAL:—

“Mayor Dunne needs to be warned against TOM JOHNSON, of Cleveland, whom he seems to regard as an all-wise authority on traction.

“JOHNSON MAKES FREQUENT VISITS TO CHICAGO in the pose of an adviser of Mayor Dunne, and Dunne visits Cleveland to absorb instruction from Johnson.

“The association for which Mayor Dunne is responsible, is scandalous and disgraceful. It should be stopped in the interest of MAYOR DUNNE’S REPUTATION, which IS BOUND TO SUFFER FROM CONTACT WITH A MAYOR WHO DURING HIS TERM OF OFFICE HAS BEEN TRYING TO OBTAIN A TRACTION ORDINANCE FOR HIMSELF AND HIS FRIENDS from the Cleveland City Council.

“We are not familiar with the statutes of Ohio, but on general principles we should say that SUCH CONDUCT AS THAT OF WHICH MAYOR JOHNSON HAS BEEN GUILTY OUGHT TO BE A FELONY. The mayor of any city should be that city’s best friend and counselor. He should be on guard to protect the community against franchise grabbers. He should not use the power of his position to gain any benefits from the city for himself. WHEN HE APPEARS AS A BEGGAR FOR A FRANCHISE, HE SHOULD BE INDICTED AND PROSECUTED.

“If found guilty he should go to the penitentiary and stay there long enough to give him time for repentance.

“THAT IS MAYOR JOHNSON’S CONDITION AT THIS MOMENT, according to general report.

“HE IS TRYING TO INDUCE THE CLEVELAND CITY COUNCIL TO GIVE HIM A STREET CAR FRANCHISE with the hope, no doubt, that the existing traction companies will BUY HIM OFF AT A LARGE FIGURE.

“He knows as well as other traction men that A THREE-CENT FARE STREET RAILROAD IS AN IMPOSSIBLE PROPOSITION IN THE UNITED STATES.

“He himself, in Philadelphia and New York, where he was a street railway owner, WOULD HAVE NOTHING TO DO WITH A REDUCTION OF FARES TO THE THREE-CENT BASIS for he knew that with such a reduction his companies would go into bankruptcy.

“He knows that A THREE-CENT FARE ROAD IN CLEVELAND WOULD NOT BE A SUCCESS as an operating concern, however great might be its success as A CLUB FOR BLACKMAIL against existing companies.

“But the rate of fare has nothing to do with the right or the wrong of MAYOR JOHNSON’S ATTEMPT TO EXTORT A FRANCHISE from the Cleveland city council except as the three-cent fare factor in it shows how conscienceless a man may be when he is afflicted with the greed for money.

“THE POINT IS THAT THE MAYOR OF THE CITY IS USING THE INFLUENCE WITH WHICH HE IS TEMPORARILY FURNISHED TO OBTAIN A CONCESSION FOR HIMSELF.

“Such a man is an evil counselor for Mayor Dunne, who should refuse to give ear to his pleadings.

“Mayor Dunne is an honest man, but very ready to listen, and when he heeds an adviser as sharp and keen as MAYOR JOHNSON, WHO CAN MAKE THE WORSE APPEAR THE BETTER REASON, he is in danger of forfeiting the respect in which he is held.

“Mayor Dunne does not think of Johnson as a man guilty of what ought to be felony, but only as mayor of Cleveland and a pleasant person to meet. Doubtless Johnson, who is master of the arts of persuasion, uses that of flattery and makes Mayor Dunne believe himself to be a great and good man.

“Under these circumstances, Mayor Dunne should be especially careful of himself and hearken not to the voice of THE FAT CASUIST OF CLEVELAND.

“If he listens long to him he is likely to do something that will cost him all his friends and well-wishers in Chicago, and in exchange for them gain nothing but the SNEERING APPROVAL OF MAYOR JOHNSON, which will be withdrawn the very moment Johnson has NO FURTHER OCCASION TO MAKE USE OF HIM.

“Mayor Dunne is no match for Tom Johnson in skill and resources. He should keep away from him, therefore, and preserve his dignity without risking the loss of it at the hands of THAT ADROIT ADVENTURER.”

This is the kind of “educational campaign” the Concon was conducting through paid advertisements in the newspapers, the Press alone declining to print them, when the “financial interest” suit was on in the courts. They managed to bring the case before a pliant judge and a very stupid man withal, and they got from him the desired decision. Later, after a full hearing before a reasonable judge, this foolish verdict was set aside, but it had served its purpose of delaying the extension of the three-cent fare lines and seriously embarrassing the Forest City Railway.

When the Forest City Company found itself confronted with the probability of having all its grants declared invalid because of the “personal interest” claim they were forced to decide quickly what move to make next in order to retain the advantage the city had so far gained over the old monopoly company. It was at this juncture that the Low Fare Railway Company came into being. It was incorporated by W. B. Colver and others and financed by a man who believed in our movement and who was not a resident of Cleveland. It started free from the claim of personal interest.

The Low Fare Company bore the same relation to the Municipal Traction Company that the Forest City did. The low-fare companies were eager to push ahead and extend their range of operations eastward on Central avenue, but while the question of this franchise was in the United States Supreme Court no move could be made. At the hearing before this court the Concon was represented by Judge Warrington, already mentioned, and by Judge Sanders of Squire, Sanders and Dempsey, the Concon’s local attorneys. The interests of the city and of the low-fare line were in the hands of City Solicitor Baker and D. C. Westenhaver, who had lately come to Cleveland from West Virginia and become a partner in the firm of Howe & Westenhaver. He did most of the fighting for the low-fare companies. All the big lawyers, those of established reputation, were employed by the other side or so tied up that they couldn’t accept cases for the three-cent-fare crowd — except Mr. Baker, of course, whose public employment kept him on the city’s side. Privilege certainly had a powerful influence with some judges and it did its best to monopolize the best legal talent available. The odds against us in the whole long fight were so great that perhaps we couldn’t have gone on as we did year after year, hopefully, cheerfully — even getting a lot of fun out of it, as we certainly did — if we had been able to look ahead and foresee the obstacles and count the cost. And yet I think we should have gone on just the same.

The Low Fare Company had been granted rights for a through route from east to west on East Fourteenth street, Euclid avenue, the Public Square, Superior avenue, the viaduct, West Twenty-eighth street and Detroit avenue. All the low-fare grants, both of the Low Fare Company and the Forest City, were made to expire at about the same time, twenty years from the date of the original Forest City grant, September 9, 1923.

The New Year found the city nearer three-cent fare than it had been at any time during the six years of the fight and on January 7 the low-fare people were made very happy by the decision of the United States Supreme Court in the Central avenue case, which confirmed Judge Tayler’s decision that the franchise of the Cleveland Electric Street Railway Company on Central avenue, Quincy avenue and East Ninth street had expired in 1905. The news came to us in Judge Babcock’s court, where the Sumner avenue injunction suit was being heard. Mr. du Pont left the court room and hurried to the offices of the Cleveland Electric, where he found two or three of the company’s directors who had not yet heard of the decision. Several other directors came in before he left and he proposed that an agreement be effected whereby the injunction against the Forest City on Detroit avenue be held in abeyance, the low-fare people on the other hand doing nothing to interfere with the Cleveland Electric’s cars on Central avenue, which were to be operated at a three-cent fare. If either side wished to terminate this agreement twenty-four hours’ notice was to be given.

The Sumner avenue grant to the Low Fare Company was declared legal on January 9, so the people won another important victory.

Cleveland Electric stock went down to sixty after the United States Supreme Court decision in the Central avenue case, and immediately thereafter the old company came to the council seeking some kind of a settlement. Somehow all the disagreeable litigation didn’t seem to prejudice the car-riders, for the low-fare lines were exceedingly popular from the very start — much too popular for the comfort of the old company in spite of everything that had been done to make the project fail.

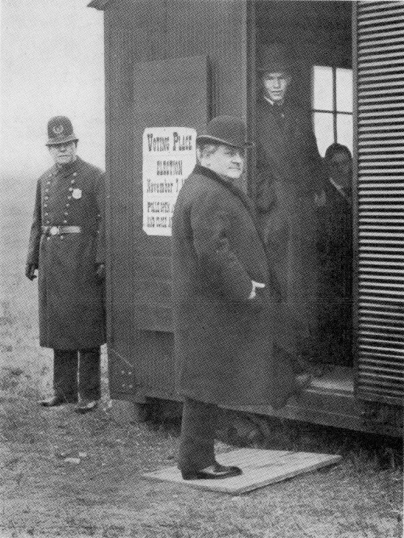

Photo by L. Van Oeyen

Tom L. Johnson entering voting booth, November 7, 1906