| 2 | Dancing in the Light |

He knew, by streamers that shot so bright,

That spirits were riding the northern light.

—Sir Walter Scott, “The Lay of the Last Minstrel,” 1802

January 7, 1997, seemed to be an ordinary day on the Sun. Photographs taken at the Mauna Kea Solar Observatory showed nothing unusual. In fact, to the eye and other visible wavelength instruments, the images showed not so much as a single sunspot. But X-ray photographs taken by the Yohkoh satellite revealed some serious trouble brewing. High above the solar surface, in the tenuous atmosphere of the Sun, invisible lines of magnetic force, like taut rubber bands, were coming undone within a cloud of heated gas. Balanced like a pencil on its point, it neither rose nor fell as magnetic forces levitated the billion-ton cloud high above the surface. Then, without much warning, powerful magnetic fields lost their anchoring and snapped into new shapes; the precarious balance between gravity and gas pressure lost.

The massive cloud launched from the Sun crossed the orbit of Mercury in less than a day. By Wednesday it had passed Venus: an expanding cloud over thirty million miles deep, spanning the space within much of the inner solar system between the Earth and Sun. At a distance of one million miles from the Earth, the leading edge of the invisible cloud finally made contact with NASA’s WIND satellite at 8:00 P.M. EST on January 9. By 11:30 P.M. the particle and field monitors onboard NASA’s earth-orbiting POLAR and GEOTAIL satellites told their own stories about the blast of energetic particles now sweeping through this corner of the solar system. Interplanetary voyagers would never have suspected the conflagration that had just swept over them. The cloud had a density hardly more than the best laboratory vacuums.

The tangle of fields and plasma slammed into the Earth’s own magnetic domain like some enormous sledgehammer as a small part of the fifty-million-mile-wide cloud brushed by the Earth. Nearly a trillion cubic miles of space were now involved in a pitched battle between particles and fields, shaking the Earth’s magnetic field for over twenty-four hours. The storminess in space rode the tendrils of the Earth’s field all the way down to the ground in a barrage of activity. Major aurora blazed forth in Siberia, Alaska, and across much of Canada during this long winter’s night.

The initial blast from the cloud (astronomers call it a “coronal mass ejection” or CME) compressed the magnetosphere and drove it inside the orbits of geosynchronous communications satellites suspended above the daytime hemisphere, amplifying trapped particles to high energies. Dozens of satellites, positioned at fixed longitudes along the Earth’s equator like beads on a necklace, alternately entered and exited the full bore of the solar wind every twenty-four hours as they passed outside the Earth’s magnetic shield. Plasma analyzers developed by Los Alamos Laboratories, and piggybacked on several geosynchronous satellites, recorded voltages as high as 1,000 volts, as static electric charges danced on their outer surfaces. It was turning out to be not a very pleasant environment for these high-tech islands of silicon and aluminum.

High-speed particles from the cloud seeped down into the northern and southern polar regions, steadily losing their energy as they collided with the thickening blanket of atmosphere. On January 9, at 8:00 P.M. EST, the darkened but cloudy northern hemisphere skies over Alaska and Canada were awash in a diffuse auroral glow of crimson and green that subtly flowed across the sky as the solar storm crashed against the Earth’s magnetic shield. This quiescent phase of activity was soon replaced by a far more dramatic one whose cause is a completely separate set of conditions and events that play themselves out in the distant “magnetotail” of the Earth.

Like some great comet with the Earth at its head, magnetic tendrils trail millions of miles behind it above the nighttime hemisphere. At nearly the distance of the Moon, the Earth’s field contorts into a new shape in an attempt to relieve some of the stresses built up from the storm cloud’s passage. The fields silently rearrange themselves across millions of cubic miles of space. Currents of particles trapped in the shape-shifting field accelerate as magnetic energies are exchanged for pure speed in a headlong kinetic onrush. Some of the particles form an equatorial ring of current, while others flow along polar field lines. Within minutes, beams of particles enter the Earth’s polar regions around local midnight, triggering a brilliant aurora witnessed by residents of northern latitudes in Canada and Europe. The quiet diffuse aurora that Alaskan and Canadian observers had seen during the first part of the evening on January 9 were abruptly replaced by a major auroral storm that lasted through the rest of this long winter’s night.

As the solar cloud thundered invisibly by, a trace of the frigid atmosphere was imperceptibly sucked high into space in a plume of oxygen and nitrogen atoms. The changing pressure in the bubble wall pumped this fountain as though it were water being siphoned from a well. Atoms once firmly a part of the stratosphere now found themselves propelled upward and accelerated, only to be dumped minutes later into the vast circumterrestrial zone girdling the Earth like a doughnut. Still other currents began to amplify and flow in this equatorial zone. A river of charged particles five thousand miles wide asserted itself as the bubble wall continued to pass. Millions of amperes of current swirled around the Earth in search of some elusive resting place just beyond the next horizon. Like electricity in a wire, this invisible current created its own powerful magnetic field in its moment-by-moment changes as current begets field and field begets more current.

FIGURE 2.1 The major regions of the Earth’s space environment showing its magnetic field, plasma clouds, and currents.

The Earth didn’t tolerate the new interloper very well. The current grew stronger, and the Earth’s own field was forced to readjust. On the ground, this silent battle was marked by a lessening of the Earth’s own field. Compass needles bowed downward in silent assent to magnetic forces waging a pitched battle hundreds of miles above the surface. The same magnetic disturbance that made compasses lose their bearings also infiltrated any long wires splayed out on telegraph poles, in submarine cables, or even in electrical power lines. As the field swept across hundreds of miles of wire and pipe, currents of electrons began to flow, corroding pipelines over time and making messages unintelligible. During the January 1997 storm, the British Antarctic Survey at its South Pole Halley Research Station reported that the storm disrupted high-frequency radio communications and shut down its life-critical aircraft operations.

The storm conditions continued to rage throughout all of January 10, but, just as the conditions began to subside on January 11, the Earth was hit by a huge pressure pulse as the trailing edge of the cloud finally passed by. The arrival and departure of this cloud would not have been of more than scientific interest had it not also incapacitated the $200 million Telstar 401 communications satellite in its wake at 06:15 EST. The storm had now exited the sphere of scientific interest and landed firmly inside the wider arena of human day-to-day life among millions of TV viewers.

AT&T tried to restore satellite operations for several more days, but on January 17 they finally admitted defeat and decommissioned the satellite. All TV programs such as Oprah Winfrey, Baywatch, The Simpsons, and feeds for ABC News had to be switched to a spare satellite: Telstar 402R. The Orlando Sentinal on January 12 was the first newspaper to mention the outage in a short seventy-four-line note on page 22. Three days later, the Los Angeles Times described how this outage had affected a $712 million sale of AT&T’s Skynet telecommunications resources to Loral Space and Communications Ltd. No papers actually mentioned a connection to solar storms until several weeks later, on January 23, when the focus of news reports in the major newspapers was the thrilling scientific studies of this “magnetic cloud.” The New York Times closed their short article on the cloud by mentioning that “scientists said they do not know if this month’s event caused the failure, early on January 11, of AT&T’s Telstar 401 communications satellite, but it occurred during magnetic storms above the earth.”

Whether stories get covered in the news media or not is often a matter of luck when it comes to science, and this time there was much that urgently demanded attention. A devastating earthquake had struck Mexico City at 2:30 P.M. on January 10 and cost thousands of lives. This had come close behind the three million people in eastern Canada who had lost power a few days before the satellite outage. In Montreal, over one million people were still waiting for the lights to go back on under cloudy skies and subfreezing temperatures. These were very potent human-interest stories, leaving little room at the time for stories of technological problems caused by distant solar storms. Although the news media barely mentioned the satellite outage, the outfall from this satellite loss reverberated in trade journals for several years afterward, extending far beyond the inconveniences experienced by millions of TV viewers. It was one of the most heavily studied events in space science history, with no fewer than twenty research satellites and dozens of ground observatories measuring its every twist and turn. Still, despite the massive scientific scrutiny of the conditions surrounding the loss of the Telstar 401 satellite, the five-month-long investigation by the satellite owner begged to differ with the growing impression of solar storm damage rapidly being taken as gospel by just about everyone else.

Although they had no “body” to autopsy, AT&T felt very confident that the cause of the outage involved one of three possibilities: an outright manufacturing error involving an overtightened meter shunt, a frayed bus bar made of tin, or bad Teflon insulation in the satellite’s wiring. Case closed. Firmly ruled out was the solar disturbance that everyone seemed to have pointed to as the probable contributing factor. In fact, AT&T would not so much as acknowledge there were any adverse space weather conditions present at all. So far as they were concerned, publicly, the space environment was irrelevant to their satellite’s health. In some sense, the environment was, in terrestrial terms, equivalent to a nice sunny day and not the immediate aftermath of a major lightning storm or tornado.

The reluctance of AT&T to make the solar storm–satellite connection did not stop others from drawing in the lines between the dots and forming their own opinions. In some quarters of the news media, the solar storm connection was trumpeted as the obvious cause of the satellite’s malfunction in reports such as Cable Network News’s “Sun Ejection Killed TV Satellite.” Aviation Week and Space Technology magazine, a much read and respected space news resource, announced that Telstar 401

suffered a massive power failure on Jan. 11, rendering it completely inoperative. Scientists and investigators believe the anomaly might have been triggered by an isolated but intense magnetic sub-storm, which in turn was caused by a coronal mass ejection . . . spewed from the Sun’s atmosphere on Jan. 6.

Even the United States Geological Survey and the United States Department of the Interior released an official fact sheet, titled “Reducing the Risk from Geomagnetic Hazards: On the Watch for Geomagnetic Storms,” in which they noted, in their litany of human impacts, “In January 1997, a geomagnetic storm severely damaged the U.S. Telstar 401 communication satellite, which was valued at $200 million, and left it inoperable.”

By January 12, the bubble wall had finally passed. The electric connection between the Sun and the Earth waned, and the Earth once again found itself at peace with its interplanetary environment. Its field resumed its equilibrium, expanding back out to shield its retinue of artificial satellites. The currents that temporarily flowed and painted the night skies with their color were soon stilled. Meanwhile, man-made lights on another part of the Earth flickered and went out for eleven minutes. In Foxboro, Massachusetts, the New England Patriots and the Jacksonville Jaguars were in the midst of the AFC championship game when at 5:04 P.M. the lights went out at the stadium. A blown fuse had cut power to a transformer in the Foxboro Stadium just as Adam Vinatieri was lining up to try for a twenty-nine-yard field goal. It may have been mere coincidence, but the cause of the “mysterious” fuse malfunction was never identified in terms of more mundane explanations. The story did make for rather awful puns among sports writers in thirty newspapers from as far away as Los Angeles.

A gentle wind from the Sun incessantly wafts across the Earth, and from time to time causes lesser storms to flare up unexpectedly like inclement weather on a humid summer afternoon. This wind of stripped atoms drags with it into space long fingers of magnetism and pulls them into a great pinwheel pattern spanning the entire solar system. The arms are rooted to the solar surface in great coronal holes, which pour plasma out into space like a dozen faucets. Just as magnets have a polarity, so too do these pinwheel-like arms of solar magnetism. North-type and south-type sectors form an endless and changing procession around the path of the Earth’s orbit as old coronal holes vanish and new ones open up to take their place. As the Earth travels through these regions, its own polarity can trigger conflicts, spawning minor storms as opposing polarities search for an elusive balance. The cometlike magnetotail region that extends millions of miles behind the Earth trembles with the subtle disturbances brought on by these magnetic imbalances. Minor waves of particles are again launched into the polar regions as the magnetotail waves like a flag in the wind. Lasting only a few hours, magnetic substorms are nothing like the grand daylong spectacles unleashed by million-mile-wide bubble clouds, but they can be the source of high-energy electrons capable of affecting satellites.

The solar surface can also create storms that traverse interplanetary space with the swiftness of light. Near sunspots where the fields are most intense, explosive rearrangements cause spectacular currents to flow. Crisscrossing currents short-circuit themselves in a burst of heat and light called a “solar flare.” Within minutes, the conflagration creates streams of radiation that arrive at the Earth in less time than it takes to cook a hamburger. Within a few hours, a blast of energetic particles traveling at one-third the speed of light begins to arrive, and provides unprotected astronauts and satellites with a potentially lethal rain of disruption. In the ionosphere, the stream of X rays strips terrestrial atoms of their electrons. For hours the ionosphere ceases to act like a mirror to shortwave radio signals across the daytime face of the Earth. The ebb and flow of the atomic pyrotechnics on the distant Sun are reflected in the changing clarity of terrestrial radio transmissions. Soon, the conditions that brought about the solar flare-up mysteriously vanish. The terrestrial atmospheric layers slough off their excess charges through chemical recombination, and once again radio signals are free to skip across the globe unhindered.

As dramatic as these events can be as they play themselves out, they do so under the cloak of almost total invisibility. Unlike the clouds that fill our skies on a summer’s day, the motions of the solar plasma and the currents flowing near the Earth have much the same substance as a willo’-the-wisp. All you can see are the endpoints of their travels in the exhalations from the solar surface or in the delicate traceries of an auroral curtain. Only by placing sensitive instruments in space, and waiting for these buoys to record the passing waves of energy, have we begun to see just how one set of events leads to another, like the fall of dominoes. It is easy to understand why thousands of years had to pass before the essential details could be appreciated.

Over most of Europe and North America, let alone the rest of the world, fewer than two nights each year have any traces of aurora, and if you live in an urban setting, with its light pollution, aurora become literally a once-in-a-lifetime experience. In bygone years, even the urban sky was dark enough that the Milky Way could be seen from such odd places as downtown New York City. Every week or so, in some localities, the delicate colors of the aurora would dance in the sky somewhere. Lacking our modern entertainments of TV, radio, and the Internet, previous generations paid far more attention to whatever spectacles nature could conjure up. For the modern urbanite, this level of appreciation for a natural phenomenon has now become as foreign as the backside of the Moon. Most of the residual legacies of fear and dread that aurora may still command have been substantially muted, especially as our scientific comprehension of the natural world has emerged to utterly demystify them. More important, they do no physical harm, and it is by virtue of this specific fact that they have been rendered irrelevant.

We understand very well the calamities that volcanoes, earthquakes, hurricanes, and tornadoes can cause. For much of human history, volcanic eruptions and earthquakes have been civilization’s constant companion, with such legendary episodes as Santorini, Etna, and Krakatoa indelibly etched into the history of the Western world. In the Far East, seasonal typhoons and tsunamis produce flooding the likes of which are rarely seen in the West. It wasn’t until settlers expanded throughout the Bahamas, the Gulf of Mexico, and the interior of North America that two new phenomena had to be reckoned with: tornadoes and hurricanes. As human populations established themselves in the New World, our vulnerability to the devastating effects of tornadoes and hurricanes increased year after year.

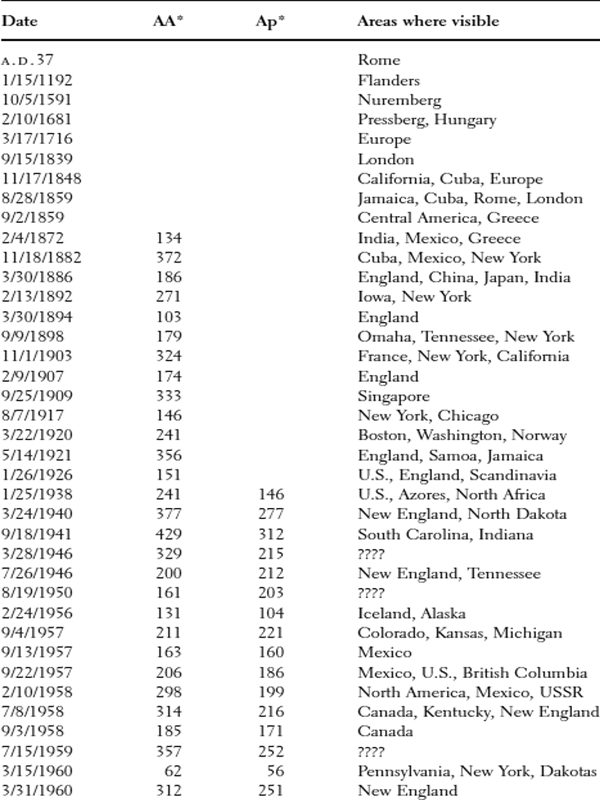

TABLE 2.1 A Partial List of Major Aurora Reported Since A.D.1

NOTE: The AA* and Ap* indices are related to the geomagnetic disturbance Kp index and was introduced in the 1930s to characterize the magnitude of geomagnetic storms. A number of apparently major aurora as indicated by large AA* and Ap* values seem not to have been reported (i.e., photographed) or considered otherwise noteworthy, especially since 1980.

Indices courtesy Joe Allen NOAA/NGDC. Aurora reports since 1940 obtained from archival editions of Sky and Telescope and Astronomy.

Like the settlers of Kansas who discovered tornadoes for the first time, we have quietly but steadily entered an age in which aurora and solar storms have become more than just a lovely but rare nighttime spectacle. During the last century, new technologies have emerged such as telegraphy, radio, and satellite communication—and all these modern wonders of engineering have shown consistent patterns of vulnerability to these otherwise rare and distant phenomena. The most serious disruptions have followed relentlessly the rise and fall of the sunspot cycle and the appearance of Great Aurora, which, as table 2.1 shows, arrive every ten years or so and are often seen worldwide. Like tornadoes, we have had to reach a certain stage in our colonizing the right niches in order to place ourselves in harm’s way.

Aurora are only the most obvious sign that more complex and invisible phenomena are steadily ratcheting up their activity on the distant solar surface and in the outskirts of the atmosphere high above our heads. When great auroral storms are brewing, they inevitably lead to impacts on our technology that can be every bit as troublesome and potentially deadly as an unexpected lightning storm or a tornado.