CHAPTER THREE

WAY OUT WEST. ORIGINS AND INSPIRATIONS

As anyone who has ever seen a Coen brothers movie can tell you, it’s sometimes possible to take things too far. Like Walter when he pulls the Big Lebowski from his wheelchair, you can get in trouble. But it can also be funny. We’d heard that many of the characters in The Big Lebowski were inspired by actual people and that some of the key sequences were inspired by actual events. Being rabid fans, we were curious. We were writing a fan book, after all. We wanted to know. But how far was too far? Would trying to pin the movie down to a set of facts and dates lessen its charm?

As anyone who has ever seen a Coen brothers movie can tell you, it’s sometimes possible to take things too far. Like Walter when he pulls the Big Lebowski from his wheelchair, you can get in trouble. But it can also be funny. We’d heard that many of the characters in The Big Lebowski were inspired by actual people and that some of the key sequences were inspired by actual events. Being rabid fans, we were curious. We were writing a fan book, after all. We wanted to know. But how far was too far? Would trying to pin the movie down to a set of facts and dates lessen its charm?

Luckily, that wasn’t a problem. We were, in fact, able to track down a number of the people who inspired characters in the movie, following a trail that eventually led all the way to the real “Little Larry” Sellers. (Who, as it turned out, had absolutely no idea he held that honor until he listened to a message we left him on his mother’s answering machine.) But as far as facts go, forget about it. What we eventually learned was that the word inspirations is the one that fits best. “Little Larry” is not actually a fucking dunce. “The Dude” was never a roadie for Metallica.

In recording the interviews you’ll find below, we found we had to forget about trying to connect the dots. What we were left with were the stories and the extremely interesting, funny people who were telling them. And at that point it was easy to see why The Big Lebowski is one of the great comedies of modern times: because it was, from the beginning, all about laughter. It started with stories that had the Coen brothers laughing so hard they were falling out of their chairs. By the time we’d finished with these interviews, we’d fallen out of our chairs a few times, too.

A (Not Quite) Interview with the Coen Brothers

Bums: Can we interview you guys about The Big Lebowski for a fan book we’re writing?

Coen brothers (via their friend Peter Exline): We let you borrow the marmot.*Don’t push it.

JEFF “THE DUDE” DOWD: He’s the Dude. So That’s What You Call Him.

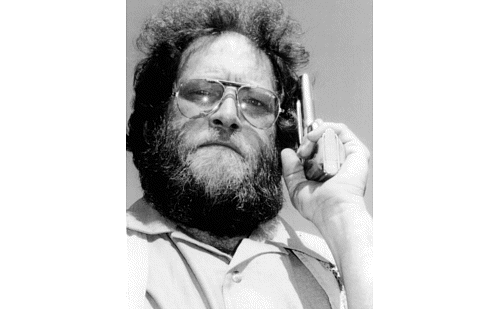

Jeff Dowd is the man around whom the Coen brothers loosely modeled the character of the Dude. Dowd was a political activist in the sixties and a member of the Seattle Seven (him and six other guys). Jeff Bridges met with Dowd as filming began and was able to mimic Dowd’s body language and speaking mannerisms perfectly.

Jeff Dowd is not a lazy man. He has been working in film production for nearly thirty years and helped land distribution deals for a number of high-profile independent films including the Coens’ first film, Blood Simple. He has also appeared at many Lebowski Fests to enjoy some White Russians and roll a few with fellow Achievers.

As a result of The Big Lebowski’s popularity, Dowd has found himself greeted by fans as an icon in his own right. He tells stories of being recognized by Lebowski fans around the world, from army colonels to Wall Street bankers to musicians and professional athletes of every stripe. And the Dude does know how to tell a story. In fact, he’s in the process of finishing a manuscript of his own called The Dude Abides: Classic Tales and Rebel Rants.

JD: Joel and Ethan and I met because it was the first year of Sundance. There happened to be a guy there who was giving money into some of Redford’s environmental causes, but he’d also put some money into the limited partnership of Blood Simple. And he asked Redford, “What should I do about this movie?” And Redford said he should talk to me, and told me a little bit about the movie.

Several months later, I was in New York City and I happened to be at the Fox office wearing a jacket and tie, because that’s what you do in New York. And Joel and Ethan show up. It’s September. They’re all grungy-looking and everything, and they’re obviously there because one of the investors said, “Maybe you ought to check this out.” They were pretty uninterested. They weren’t totally enthusiastic about pitching me this. Blood Simple is a pretty tough movie to describe, right?

And so we met for a while, and they left, and I could tell that it didn’t go real well. And who knows when some indie guys pitch you something, right? They weren’t trying real hard. I looked like the suit from this stereo version of, Fox to them.

So by chance later that night, I’m walking in Greenwich Village and I run into them again. And now I’ve got my leather jacket on, and we talk on the street for a few minutes, and then by even more fate, about one in the morning I was at an IFC party at a loft in the Village, and there they were again. So we had a couple of drinks. At that point we knew there was some destiny working.

So in due course they showed me the movie. In the first few minutes I went, “Wow! These guys are real filmmakers.” You could tell right away. They had a real kind of unique voice and style. And so they asked me to represent the film, which I did. And we spent the next quite a few months, almost a year, getting turned down by every distributor three times. Every single one. They all looked at it and shrugged their shoulders and went, “No.”

We spent a lot of time. I remembered the other day that New Line and New World both turned us down on the same day. And we said, let’s just go get a bottle of Jack Daniel’s and we’ll rent Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia.

One of the discoveries I made at that point is that you couldn’t really show a black comedy to people without an audience. We finally arranged to show it at the Toronto Film Festival, where probably about eight hundred people were. And then an amazing thing happened: People started laughing. And then we had a minor bidding war, and we ended up selling the film.

Bums: Do you remember at what point they found out that you called yourself the Dude?

JD: The story on the Dude is I started to be referred to as the Dude in sixth grade when I was living in Berkeley, California, and two guys on a baseball team named Abe and Danny started calling me the Dude. And then when my father moved us back East, kids there started calling me the Dude, too, based on my size and stuff like that.

Unlike in the movie, where Bridges tells people to refer to him as the Dude, I never did that. But that name then started to pick up and people started to use it. And then, years later during the war movement, we would go to these conventions and all the guys from Cornell would refer to me as the Dude. And so people started to use that name.

So people from around the country in the SDS [Students for a Democratic Society] started calling me the Dude and hearing that name. Our chapter was kind of like the coolest chapter: best organized, and we partied the best. So that name got attached to Jeff Dowd.

So Joel and Ethan are so well read that they read that in some article or some book. And one day, they called me on the phone—they used to like to get on the phone together—and Ethan said, “Dude? Duder? Duderino?” And whenever they would talk to me, they would get on the phone and I’d hear this stereo version of, “Dude? Duder? Duderino?” All the stuff that’s in the movie. They just liked riffing on the name a lot.

Bums: What parts of the movie were actually based on your life?

JD: I was never a roadie for Metallica! Although, ironically, I ended up working with them on their movie.

Me and six other guys

The Seattle Seven, also known as the Seattle Liberation Front, was started in 1970 by University of Washington professor Micheal Lerner as a result of the breakup of Students for a Democratic Society. Members included Micheal Abeles, Joe Kelly, Micheal Justesen, Susan Stern, Roger Lippman, Jeff Dowd, and Chip Marshall.

Basically, I think what Joel and Ethan were doing is, they wanted to create—as is the case in many great movies—these opposites. And there is almost always one guy who gets the other guy in trouble.

So, you know, Butch is always getting Sundance in trouble. Tony Curtis is getting Jack Lemmon in trouble in Some Like It Hot. Mel Gibson is getting Danny Glover in trouble in Lethal Weapon. And so Walter is the guy who is always pushing and getting the Dude in trouble.

And they froze two guys in time. They froze what we might’ve been like, and we were a little bit like that to a large extent in the seventies for a year or two, after the political activism died down and before we went back to work. We were hanging pretty heavy in Seattle. And we were, indeed, drinking White Russians for a while, somewhere in between tequila sunrises and dirty mothers and Harvey Wallbangers.

Bums: Do you remember how the Coens picked up that little detail about the White Russians?

JD: That I don’t know. But what you should know, though, is how all this stuff came up. Writers write what’s funny. Or they write where there’s conflict. And White Russian is a funny name for a drink. You can riff on it.

They like stuff they can take from and do something with. Very early on, I asked them, “How do you guys write?” And Joel said, “Well, I’ll write a scene and I’ll make it as difficult as I possibly can for the character.” And Ethan said, “And I’ll make it worse.” And then Joel said, “And then I’ll make it worse again.”

Making the situation worse is what all great drama and all great comedy is going to come out of. So if you look at The Big Lebowski, or you look at Fargo, or you look at Raising Arizona, you’ll see how things progress: Things get worse and worse and worse.

As for the bowling thing, I can give you my take on why I think that happened. When we opened Blood Simple in L.A., I was in charge of the L.A. party because I lived there and I had an idea that I thought was interesting: to throw a party at a bowling alley. And this is before bowling alleys became trendy. I thought it might be an interesting location.

So I found a little bowling alley in Santa Monica, and it turned out that the upstairs bar, this big room that had been sealed for years, had actually been the secret hideaway for the Rat Pack. Sammy Davis Jr. and Sinatra and Dean Martin would stay there on their way to Peter Lawford’s place about a mile away in Santa Monica. And this was like their own little place. Nobody knew that.

And that night at the party we had bands and music—almost like Lebowski Fest—and it was really rockin’. And I rolled a few, of both kinds, and everybody was having a great time. And I think it was pretty much there that Joel and Ethan observed me bowling and saw this kind of wild time and camaraderie that takes place, and they got the idea for the Dude bowling.

Bums: Just a little bit more about the character of the Dude. What parts of the character that Jeff Bridges portrayed did he get from you?

JD: He got all the physicality. But it’s not just Jeff. It’s also Joel and Ethan. When my kids saw the poster of the movie, they said, “Daddy, where’d they get your clothes?” Those weren’t my clothes, but the costume designer got it, you know?

I mean, that’s what good directors do: They work with pretty much the same team on every movie, right? And so she got that, and so did Bridges. All the physicality. The slouching, the belly, the clothes. In the original script it describes the Dude as a man “in whom casualness runs deep.”

The car, by the way: In the original script it actually called for the car I used to have, which was a Chrysler LeBaron convertible. When it came time to shoot the movie, they couldn’t get Goodman into a Chrysler LeBaron. I mean, you could shoehorn the guy in there, but it wasn’t big enough so that he could turn and look at the Dude. So they needed a big car like a Torino, because the LeBaron wouldn’t fit for Goodman.

The phrase “Dude here” comes from one time I was at the Venice Film Festival with Blood Simple and they weren’t there, but they knew to call the hospitality suite to look for me. And the phone kept ringing, and I picked up the phone and said, “Dude here.” And they got that line right there.

Bums: So let’s talk a little bit about the fans and the cult following that has grown up around this film. Do you have any theories on what it is about the movie that has spawned this reaction in different people?

JD: To some degree. I know because I talk to an awful lot of people, and some in different ways than you guys. You guys see them mainly in the context of Lebowski Fest, but I see them everywhere. Often in different countries, even. I see a lot of them at Lebowski festivals, but also a lot of people who haven’t been to Lebowski Fest. They did a Lebowski showing at Berkeley last week.

So there are a few things. Obviously you’re taking a situation where the film didn’t do that well in theaters for various reasons but took off as a DVD. And then it ended up having this following. The figure I heard is that it has sold something like twenty million DVDs.

Anyhow. It’s a lot of things. People like to repeat the lines of The Big Lebowski. Because they’re such memorable and classic lines. And of course you can use them, as we’ve seen, in all kinds of other contexts. And people do that all the time. I’ve even heard that there’s a Wall Street firm that when they’re interviewing people, they throw out a few of the lines in the interview and see if people pick up on them, and they don’t hire them if they don’t.

Then, this is a movie you can see with your friends. Or your family. It is really enjoyable to see with other people. And it doesn’t matter: You can be drunk, stoned, baked, it doesn’t matter. It’s a movie you know you’re going to feel better while watching the movie or after the movie than you felt at the beginning.

I talked to a family that watches it on Thanksgiving. After dinner, the whole twenty-five of them get together and watch The Big Lebowski. And these aren’t a bunch of hippie types, but they watch it because they just know it’s going to make them feel better. And they’ve been doing it for five or six years now. And that’s the tradition, instead of watching the Detroit Lions football game. Which is not going to make them feel better, particularly if you’re a Detroit Lions fan.

Or then there is the story of the 9/11 fireman. He’s a volunteer fireman who was at 9/11. He’d seen people die before and he’d saved people’s lives before, but he’d never seen people taking their own lives as they did when they were jumping out of the buildings. And he lost a lot of friends who were firemen that day. He was absolutely psychologically devastated. His life went to pieces. He was a horrible husband, he was yelling at his kids, and he went to doctors and shrinks and took all kinds of pills.

And then one day, about six or seven months later after 9/11, he’s sitting there in his living room—he wasn’t working at the time—and he looked on his shelf and he spotted the DVD of The Big Lebowski. And he put it in the DVD player and started watching it. And he said, “For the first time in six months, I smiled and I started laughing.” And he kept laughing. And he watched it again and again. So The Big Lebowski was the thing, the drug, if you will, that brought him out of his posttraumatic stress syndrome.

The other phenomenon is, I think, the DVD revolution, so to speak. If you’re traveling and you have five or ten DVDs, The Big Lebowski is often one of them. Which means everybody on every sports team has seen that movie. You cannot find athletes, or guys who travel, who haven’t. Guys in the army, rock ’n’ roll bands, all of them, they all watch the film again and again.

It’s like a great record album. Some record albums have two or three hits on them. And some have twelve or thirteen. And in the sequence of The Big Lebowski, there are like ten or twelve great classic sequences. The Jesus sequence, Larry Sellers—there are so many of them.

So you’ve got all these things working at once: watching it together, repeated viewings, and then it’s just one of the few DVDs. And you put that all together. And it’s also a com mon discovery. People bond on their values. And when friends discover that they both like The Big Lebowski, kind of like you guys did, it becomes a bond. They can watch it together, or talk about it. It’s just like when you find a baseball team that you both like, or a band that you both like. You find this movie that you both like.

But I’m not so sure that you have people talking at length about how they both like Brad Pitt. Even though he’s a very good actor. Or George Clooney. You know, George Clooney is a great actor, he’s a great director, he’s a great producer, but I don’t think you’ve had too many conversations that last too long, more than a few sentences, between anybody—between women who might find him cute or anybody—those kinds of conversations don’t usually last more than a minute. A Big Lebowski conversation can last an hour.

Bums: So what’s it like to be the Dude?

JD: It’s this great gift, this icon status that Joel and Ethan have laid on me. It allows me a platform to do political and cultural and spiritual discussions. And so I think I’ve turned it into a really good thing. And I try not to abuse it too much.

The Stranger Says …

“Dude here.” The Dude is in every scene except for the one where the nihilists have breakfast.

PETER EXLINE: His Rug Really Tied the Room Together. His Car Was Also Stolen. (Separate Incidents.)

We first learned of Peter Exline via an e-mail from one of his students. She told us that he was one of the inspirations for the story line of The Big Lebowski as well as one of the inspirations for Walter. Exline, she told us, is a film professor at USC, and she went on to relate how once while pacing back and forth during a lecture, he bumped into a chair. After bumping into it several times, he finally got fed up and threw it across the room, shouting, “First Vietnam, now this chair!”

Exline met the Coen brothers at a Super Bowl party and later, while playing host to them at a small get-together in his backyard, told them a story about how his car was stolen and then recovered—with the addition of an eighth grader’s homework stuffed between the seats. While telling the Coens this story, he would often pause and point out how the new rug he had recently acquired “really tied the room together.” The Coens call him the “Philosopher King of Hollywood.” This is the story of his rug, his stolen car, and his visit to an eighth-grade delinquent. It made us laugh to beat the band.

Peter Exline: Barry Sonnenfeld and I were buddies at NYU, and I was working for a producer in Beverly Hills, Mace Neufeld. Barry introduced me to Joel and Ethan. They were trying to raise money for this screenplay they’d written called Blood Simple. And later that year, I was back in New York for a birthday party, and it was Super Bowl Sunday, and Barry had me over—along with Joel and Ethan. I think that’s when my humor kind of charmed them.

I think I kind of won them over because of the way I teased Barry. I was the suit from Beverly Hills when they first met me, and they were trying to figure out how to play this. And then when they saw that I was actually pretty funny and kind of abusive toward Barry, they kind of said, well, this guy’s gotta be okay.

So I had them over for dinner and a neighbor had moved out, and I’d gone over and scoped out their place and saw this old faux-Persian rug on their floor. Now, any New Yorker worth his salt knows that if somebody has left behind furniture, that means, “I don’t want it. You can have it.” I knew people in New York who had decorated entire apartments without ever buying any furniture. They decorated their entire apartments with what they saw on the street and what the neighbors had left behind. So I had rolled this faux-Persian rug up and laid it down in my living room, and I was joking to them about how it tied the room together. And Joel and Ethan were there and some other friends were there with their girlfriends and wives, and I was barbecuing some chicken and telling this story about my car being stolen.

You know how you milk a joke? All night long, I kept talking about Lew [Abernathy, a friend of Exline’s who was also an inspiration for Walter, see interview page 106] and my car, and I’d stop and I’d say, “Doesn’t this rug really tie the room together?” Every time I said it I got a laugh. Joel and Ethan just seem to think I’m so funny.

But my car had been stolen, and Lew and I were buddies. Although we didn’t call him Lew. We called him Big Lew.

Bums: He was a private investigator, is that right?

PE: He had done everything. He was a Vietnam vet. He had fought in Angola. He said he almost got killed in Angola by a fuckin’ Russian hand grenade. Then he worked in a photo shop, developing, and these private investigators would bring in this really bad footage, and he said, “You know, I could do this.” So he became a private investigator trying to catch husbands cheating on their wives and wives cheating on their husbands.

And then he went to USC, the Peter Stark program, which is a really elite graduate school. Especially for producers, and kids are kind of guaranteed to get a job when they graduate. And then Lew crewed and wrote, and he sold a script. John Cunningham directed it—Deep Star Six.

He’s this big Vietnam vet, and we’d have breakfast on Santa Monica Boulevard in West L.A. at a place called the Cafe 50’s that had a 1950s motif. It’s still up there. So my car gets stolen, and Mr. former private eye Lew Abernathy says, “No, you’ll never see your car again.” Because he knew—he knew because he’s a private investigator. “You know, it’s some guy, he ran out of gas, he jumped into your car, you live near the freeway, he jumped into your car, he’s headed to San Francisco or Bakersfield or God knows where, and he’s just gonna dump it and grab another one. You’re never going to see your car again.”

So ten days later I got a letter from the L.A. police department. My car had been impounded. I had about a half a dozen parking tickets. It was in an impound yard really close by. So I called Lew, and we go down to the car. And it’s pretty beat-up—the front left tire is gone, and they got that little fake spare tire out of the trunk on there, and it looks like a little rubber toy tire. And the backseat is filled with junk. There was a basketball and a Hard Rock Las Vegas T-shirt, and there are all these fast-food wrappers.

So I reach into the trunk and there is a cassette in there, a homemade soul tape. So I’m looking at it, and I happen to know of this cult in Brentwood. There was a guy who was a former schoolteacher who had decided that he’s the 375th reincarnation of Jesus Christ. So he’s got this cult, and it was a tape of the soul, you know. It wasn’t Aretha Franklin. It wasn’t Motown.

So Lew makes this big pronouncement. He’s determined that there are three guys who stole my car. He said there are three of them and the guy in the backseat is really big. Like, the only guy who ate any food was the guy in the backseat. And the other two guys just drove him around to Burger King.

So I’m telling this story and I’m barbecuing, and my buddies are there, and Joel and Ethan are there, and, like I said—every now and then I’d stop and I’d say, “Doesn’t this rug tie the room together?” And everybody laughed.

So then Lew on his own reaches under the passenger seat of the car. He pulls out this eighth grader’s homework.

Bums: Oh, my God.

PE: And it’s Jaik Freeman. And naturally Lew says, “Well, you’ll never find this kid.” And you may have noticed that Lew has been wrong about everything. “You’ll never see your car again.” “There’re three of them.” And that’s the point of my story. That’s why I’m telling it to Joel and Ethan.

Now, I’m sure that when Lew told you about the car, he had a very different take on it.

Bums: Yes. He was right. He thought that he had gotten straight to the correct version of events.

PE: Of course. That’s the other thing about Lew: He’s like George Bush—he’s always right. If there had been mistakes in the past, Lew didn’t make ’em. So, now, I know one fourteen-year-old kid in all of L.A. And he hangs out down at the convenience store where I get beer and cigarettes and soda and cups of coffee. So I go down to West Side Junior convenience store that night and there’s Nick, the only fourteen-year-old kid I know in all of L.A. So I say, “Nick, hey, how you doing? Do you hang out with Jaik Freeman?” And he backs up a step, looks at me, and says, “Nooooo …”

And as I’m leaving I say, “So, where do you go to school?” And he names the school, and it’s about six blocks from my apartment. So I go home and I get out the phone book and I start calling all the Freemans: “Hi, I’m looking for the parents of Jaik Freeman that goes to such-and-such junior high.”

And the eleventh phone call this woman says, “Yeah?”

And I say, “Mrs. Freeman, hi, I’m Peter Exline, I live at Ohio and Greenfield. My car was recently stolen, and it has been recovered, and I have found your son’s homework in my car.”

And she says, “Oh, my God.”

And so now I’m talking to Mrs. Freeman and I’m trying to save her son from a life of crime. And probably trying to get five hundred dollars out of her. Because I figured my car is totaled or close to it, and my deductible is five hundred dollars. So I make a date to go over there Friday night. And I call Lew, and Lew comes and picks me up, and we drive over there. And it’s a real nice neighborhood. It’s Westwood. And we’re driving down the street and I’m looking at a piece of paper, the directions, and I say, “Okay, it’s that house,” and Lew drives by it. I say, “Lew, what are you doing? The house is back there.”

And he says, “I want to make sure there’s not a setup.”

“So this housewife has got a team of ninjas in the trees?”

So he performs an illegal U-turn, and we go up and knock on the door. And it’s this really nice two-story Spanish house, and Mrs. Freeman comes to the door. Mrs. Freeman is English, she’s in her fifties, very Tiffany, very well appointed—she’s got a nice oxford-cloth dress shirt and a teal-green sweater, and beautiful silver-blond hair and a pageboy haircut. She’s not all that happy to see Big Lew.

So Mrs. Freeman lets us into the house, and little Jaik waddles down, little kid from the second floor, not too happy to see us, and I notice the house is a little bit cramped, a little bit dusty. Nothing excessive. We go from this little foyer into the living room, and my eyes practically pop out of my head because across the living room where most people have a fireplace is a hospital bed and a guy in the hospital bed—seventy-five, eighty years old—chain-smoking unfiltered Camel cigarettes, reading underneath a rack of track lighting.

So we start talking, I’m telling my story. And I didn’t even notice it, but Lew has a briefcase. Now he flips open this briefcase and he brings up a Whopper wrapper in a baggie. He’s holding this up like he’s Perry Mason in front of a jury. And then he slides that back into his briefcase and I’m talking, and he pulls out another baggie, and this one is Jaik’s homework. And he gets up and he walks over to Jaik and stands right in front of him. He says, “We know you did it, Jaik. We know you took the car.” And he shows him this homework.

When I told this at the dinner party, Joel and Ethan almost gagged. They were laughing so hard that this guy has got Whopper wrappers and homework in baggies. This part particularly inflamed their laughing motors.

So, you know, I finish my presentation and Mrs. Freeman says, very nicely, very politely, “Well, my son loaned his math book to another kid and the kid never returned it. He’s never been in your car. He didn’t steal your car. He does have an idea who might have stolen your car, and if the police call and ask, we’ll be glad to tell them.”

So I’m thinking, okay, she’s talked to a lawyer and she’s well aware of her rights and her position. She doesn’t have to give us any information. And that’s a brick wall. That’s a stone wall. I’m not going to get around that. I’m not going to get through it. And I’m too smart to beat my head against it. So I said, “Okay, thank you very much. I really appreciate it.” And we get up and we leave. And we’re getting into Lew’s car, and so as we drive off he says, “Did you see what the old man was reading?”

I say, “No, why?”

“Screenplays.”

So now I’m curious. Here’s this guy, he lives in a hospital bed, and it’s like a Raymond Chandler novel, this guy’s in a fucking hospital bed in his living room and he’s reading screenplays.

So I go home and I get out my Encyclopedia of Film and I look up this guy Everett Freeman. He had a thirty-year career in Hollywood. He’s a writer-producer. And his first credit is Larceny, Inc., Edward G. Robinson, ’39 or ’40, all the way up until the seventies. He created and wrote the Glass Bottom Boat, and he’s in a hospital bed in his living room, smoking, and his kid’s fourteen. I don’t see them out in the backyard playing football a lot. So I can understand where this kid might have some interesting hobbies.

So back at the dinner party, there is another guy there who is very funny, and he started telling Lew stories, and we spent the whole night practically in Lewville. Just telling stories. And that was June of 1989. And then in 1992 I was talking to Joel, and he said, “Hey, I wrote a script about your buddy Lew. But we changed his name to Walter because we don’t want to embarrass the guy. Do you want to read it?”

Well, I was very flattered. They had never asked me to read anything. So they sent me the script and I read it, The Big Lebowski. And I didn’t get it. I thought the guy in the opening scene was Walter, the guy who was walking around in the grocery store and opening the carton of milk and tasting the milk and getting a little milk mustache and going up and writing the check for sixty-nine cents. I said, “Oh, this is Lew.” And I forgot all about it. Until this guy told me he’d read a magazine article and the new Coen brothers movie is based entirely on my life.

And I still tell this story to my kids at USC. Which I think is absolutely pathetic. Over eight years ago. So now the kids at USC, they tell each other, “Oh, I’m taking a class from this guy that The Big Lebowski is based on.” So these kids come into my class and they want to hear about how I’m the Dude. And I very carefully pass out this article and I say to them, “As you can see, Walter P. Sobchak is based on me, John Milius, and Lew.” And the Dude is somebody completely different—that guy is Jeff Dowd.

But Joel and Ethan think I’m funny, a very funny guy. And one time they were in town and we were at dinner. And it was like January 1991. And we were kicking ass in Iraq. We’d bombed Iraq for about six months and then we attacked. Only it wasn’t Iraq. It was Kuwait. And about forty thousand soldiers from the Iraq army surrendered.

Well, I felt embarrassed, you know, as a Vietnam veteran. As you recall, we lost that war. However, I do want you to know that when I left, we were winning. So I’m having dinner with Joel and Ethan, and I’m feeling kind of anxious and uneasy here, and I think I need to explain things to them, and I said, “All right, guys, you gotta understand. It’s a lot easier to fight a war in the desert than it is to fight in canopy jungle.”

Well, I thought we were going to have to call 911 and get oxygen for Joel. I thought he was going to hit the floor. He was laughing so hard. And so I get invited to the screening at the Writers’ Guild and there is John Goodman, lacing up his bowling alley shoes, and he’s talking to Jeff Bridges and he says, “Dude, you gotta understand, it’s a lot easier to fight a war in the desert than it is in triple canopy.” And I’m like, “What the fuck?” and I turn around and look at the doorway, and there is Joel. He’s looking right at me. And laughing.

So I kind of milk this story. To this day, I’m still telling my classes. And one night I came home from class at USC, and my little phone-machine light is blinking—that little red blinking light—so I push the button and I get this message: “Listen, Exline, it’s Lew. Lew from Texas. Listen, I didn’t see this movie when it first came out. But I just rented The Big Lebowski, and I think those guys owe us money.”

Bums: Do you have any idea what it is about the movie that resonates with people?

PE: I really think that it’s just the humor. If anything, if I had to analyze it beyond the humor, it’s the perfect adolescent movie because the Dude is a guy who just refuses to grow up, and the other Lebowski is like the nightmare father. Here’s this guy who is just, like, doing what he wants to do, getting stoned and bowling and outsmarting the man. It’s a movie that each viewing I notice something that’s funny that I never noticed before. So in that way, it’s kind of a gold mine.

Bums: Now, why do they call you “Uncle Pete”?

PE: The full title is “Uncle Pete, the Philosopher King of Hollywood.” And at the beginning of our conversation I said that when I first met them, I was working for Mace Neufeld in Beverly Hills, a Hollywood producer.

Ethan is a philosophy major—he got a PhD or a master’s from Princeton in philosophy. And I had dropped out of philosophy. I was trying to get a master’s at Oregon, a PhD at Oregon, and he had every philosopher synthesized down to one line.

Socrates: “Can we know what it is? No, never.”

Descartes: “This is what it is. It’s this and not that.”

And Aristotle says, “This is that and that is this.”

And Kant: “The mind is a meat grinder and knowledge is a hamburger. Can you know if it’s kosher? No, never.”

And Ethan had a shitty job where no one had been able to last more than a week. It was typing columns of numbers for Macy’s. And he’d had it for a year and a half. And nobody before him had ever lasted a week.

Now, I was a guy from Hollywood. I was a guy in a suit and tie. So they kinda figured I knew everything. I knew the business. I knew what was going on. And they were just cubs trying to figure it all out. So Ethan came up with Uncle Pete, the Philosopher King of Hollywood. It’s the only thing I can figure.

Bums: Has your relationship to Vietnam changed? Is there a period when you were a bitter Vietnam vet? Or was that just all in humor?

PE: No. A former student of mine sent you the e-mail and told you that you can’t have Lebowski Fest without Pete Exline, because the whole thing started with him. I did not pick up a chair. I did not throw it across the room. I kind of shoved it with my foot, which looks like I’m kicking it. And I use that joke every semester: “First Vietnam, now this chair!” And I use that joke every semester just like I use the joke, “Let me tell you one thing about Vietnam: We were winning when I left.” That’s just Ethan’s exaggeration to amuse himself.

And the same with how it became a ratty little apartment and a shitty little rug. That’s just Ethan changing things around to keep himself from falling asleep because he’s so bored with, uh … the thing about Joel and Ethan is, once they make a movie, they don’t want to ever talk about it again. And if you go up and say, “Wow, I really liked this,” they’re kind of like, “Yeah, well, that’s over.” So they obviously have terrific imaginations. You can look at their movies and see that they hardly ever imitate themselves. They hardly ever repeat things.

And they generally try to turn everything into a joke.

“BIG” LEW ABERNATHY: “We’ll Brace the Kid. Should Be a Pushover.”

After Peter Exline told us of his friend whose idea it was to put the homework in a baggie and brace the twelve-year-old kid, we tracked him down and invited him to a Lebowski Fest. When he showed up in Austin, a fan rushed up to us and exclaimed, “Lew’s here! He’s cool as a kite, but I think he might be Amish.” Upon further investigation we discovered that he was not, in fact, Amish, but that he’s been just about everything else, including a private investigator (brother shamus), treasure hunter, screenwriter, and actor—his most notable role being one of the two submersible pilots in James Cameron’s Titanic.

It is said that Big Lew is one-third of the inspiration for Walter (Exline plus Abernathy plus Milius, divided by John Goodman, equals Walter Sobchak). When Lew e-mailed his buddy James Cameron to let him know he was the guest of honor at Lebowski Fest, Cameron replied, “Congratulations! After thirty years in the film business, you are the inspiration for one-third of a fictional character.”

Lew Abernathy: I finally get to set the record straight. I went to North Texas and studied philosophy and political science, then drifted to business. Ultimately I wound up in film. And then after I left North Texas, I went out to California and I started going to USC. I went out to USC and got my master’s in cinema.

USC is an expensive private school, and so my day job, or night job, was that I was a private investigator. That’s how I paid for film school. I fell into it out of a lifelong search not to have a job. In this respect, I am the Dude. I’d rather coast.

My firm was called L.A. Investigations, and I was a private investigator for fifteen years. When I met Peter Exline he was a studio executive at Universal, and Peter and I would hang out and have coffee in the morning, usually a place called Cafe 50’s. Kindred spirits. We’re both very much Wal-teresque: loud arguments and plenty of coffee.

So one day he calls me and says, “My car has been stolen.”

So, okay, And? We do live in Los Angeles. So he says, “What do I do?”

I say, “Well, did you call the cops?”

He says, “Yeah, I called the cops and the insurance company.”

And I said, “Well, you’re done.”

And he said, “Well, what happens?”

And I said, “Well, there are several scenarios. Either it got chopped and you’ll never see it again; or it was used in the commission of a crime, in which case they’ll find it but they’ll hold it for twenty years as evidence; or they went on a joyride, which means they left it abandoned someplace, someone will tow it, and then a week or two later you’ll get a card from the impound yard and you get the privilege of going down there and bailing your own car out. Because they charge you for towing and storage. More than the car is worth in a lot of cases. You see some real derelicts down at the impound yard.”

So we go down to the impound yard and sure enough the car is there, and Peter is talking to the guy who runs the impound yard, who I guess is a policeman, but it seems to me is one rank up from dogcatcher.

So Peter is like, “Do you have any leads?” And the guy at the impound yard, to my mind, is exactly like the guy in the movie. “Oh, yeah, leads, we got tons of leads. We got the whole force working on it!”

So while that was going on, I was checking out the car and telling Peter, “You know, it’s not that bad.” They busted out a gull window or maybe the rear window, and they tore up the transmission like idiots. They were clearly amateurs. And there were all these hamburger wrappers in there, literally dozens of them. They were just all over the car.

Bums: Sounds like a joyride situation.

LA: Yeah, it was. And so they’d gone to McDonald’s, and I’m looking and there are these books, and it’s like high school history, eighth-grade chemistry, or something. And I say, “Peter, are you going back to school?”

And he says, “What are you talking about?”

I said, “Are these your textbooks and your homework?” What was interesting was that the impound guy was giving the last of the zingers trying to prove to Peter that stolen cars are such a low priority and there is no way they can ever find these guys.

And so I whip out the homework and say, “Yeah, like maybe this guy? Start with this guy?” It was a pretty funny moment there.

And so we found the homework. And for whatever reason, Peter was on this real quest to try to set this kid on the straight and narrow.

He says, “I want to confront this kid.”

And I say, “Bro, just turn it over to the cops and be done with it. You got your car back.”

But he says, “No, I think I want to do this.” It was like three or four days he debated it. So finally he contacted the boy’s family, the mother or whatever.

I put on my best suit, what I called my court suit, just like Walter. And I had put some of the McDonald’s wrappers in my briefcase. First of all, I had dusted them for prints. Not really—I hadn’t lifted any prints, I just put the dust on there so that they’d show up, you know? And I put one in an evidence bag. And then I took the homework and I dusted it and I put it in an evidence bag, and so we drive over to this house in Westwood.

So we knock on the door and this really nice British lady, middle-aged, very proper, opens the door, and first of all, Peter hadn’t told her I was coming, so immediately she’s pissed off. That was a complete surprise to both of us. And of course she treats me like I’ve got leprosy.

We go in, and we go into the living room, and this is where the movie takes over, with the exception of the iron lung. The father has got IV bags and oxygen. He’s very alert, he’s watching us, he can tell what’s going on. And behind him is a wall of screenplays and awards.

And I’m going, “Peter, what have you gotten me into?”

Bums: So, having gone to film school, did you recognize the name and know him?

LA: The thing was, we didn’t know who he was. We didn’t know who he was at first, but one look and I’d been in enough writers’ homes to know that this guy is the real deal, he’s a writer of some note.

Bums: Not exactly a lightweight.

LA: No. It was a nice house, a nice neighborhood, too, and the guy is just laying there and never says a word.

And we sit down and she brings the kid down. And that’s when I basically did the Walter thing. I opened the briefcase—“Is this your homework, Larry? I’ve dusted it for prints, Larry, so don’t lie!”

The kid said that he didn’t steal the car, but he was riding in it. And so I said, “Well, I’ll give you a choice.” I said, “You need to do one of two things. You can either tell me who was in the car, or you can tell the police. But we’re gonna find out who stole the car. And right now you’re our best lead.”

And so he’s looking over at his mother, and she says, “Can we have twenty-four hours to think about it and discuss it?”

He has health problems

The Iron Lung was invented by Phillip Drinker and Agassiz Shaw of Harvard Medical School and used primarily during the polio epidemic of the 1940s and 1950s.

And I say, “Sure. It’s the weekend. I’ll wait till Monday.” And then I kind of gave some tired old speech. Peter did the talking at first, but Peter was insane. Babbling on and not making any sense. And I’m trying to get to the point so that we can get the hell out of there.

Bums: “Dude, please. I’ll handle this.”

LA: [laughing] Yeah, right. “You’re killing your father, Larry.” No, but what I did say, because I’d seen his homework, was, “You need to spend more time with your homework and less time joyriding with your friends. Because let me tell you something, it looks here like you’re just a half-assed student, but you’re a fucking lousy criminal, kid. You need to give up the crime aspect of this right now.”

What was really weird was I don’t think any of us—me, Peter, the mother, or the son—mentioned that there was this dying man in our midst. It was kind of like we all just didn’t say anything about him.

That was pretty much the end of it for me, thank God. But I was always curious, because there were a couple of other things that happened to me as a private investigator. I was working a case in Malibu, which, as you can imagine, is like rich hillbillies. It’s very incestuous, nepotistic. I was working a case where I had to watch some people, and they called the cops on me, even though I was in a public place.

Bums: They knew that you were surveilling this person?

LA: Yeah, they pinched me. I got busted. I was probably trying to dress up like a surfer or something. So they dragged me in to the sheriff, and he said, “What are you doing?” And I said, “I’m working a case.”

He wanted to know all the specific details, and I told him to go fuck himself, and he bounced a coffee cup off my head and threw me out of town. And the cup broke when it hit my head.

Bums: Did you call him anything?

LA: I think I might’ve said something ugly. And he did say something about, “I don’t like your face, I don’t like you …” He had a whole speech, and you can tell it was a stupid speech that he gave to other people, this canned speech. The guy was coming off like he was freakin’ Kojak. And he did use those immortal words, “Stay out of my beach community!”

Bums: What was the time frame on this sheriff story?

LA: That would have been mid-eighties.

And then the other thing was the scattering of the ashes off the ocean view. Apparently this is something that happens every six months like clockwork. Dipshits go up there and try to scatter their ashes into the wind. And when I was at USC, a film student got killed in a motorcycle accident. He didn’t have any family, and it was kind of up to us to bury him. But we didn’t use a coffee can. We had him in a baggie. And his girlfriend was there too. And two guys were trying to scatter the ashes into the wind—which is stupid—and it all blew back on all of us.

But the thing about it was that the guy was still partially in the bag, and it had kind of gotten wet, so it’s kind of pasty, and it was really a disaster. And we’re all just covered with this guy. And finally, at the last minute, he shakes out the last little bit—and this is before they started using grinders, apparently—and a chunk of bone about that big [makes size of a quarter] bounced out and landed right at his girlfriend’s feet. And she just passed the fuck out right there.

I was standing there going, “Okay, well, this is not what I want my funeral to be like.” But the thing about it is that my understanding is that that particular scene has played itself out at various locations up and down the coast since time immemorial.

Then I worked this case one time where it was marital infidelity. It was stupid—rich people, they were insane—and the house I went to, it was so much like Sunset Boulevard. You go to the creepy old house, and you knew it used to be somebody’s house, but it was a little bit in disrepair.

And so I ring the doorbell, and the butler or manservant says, “Mrs. So-and-so is back here.” And so he leads me through this house, which is clearly big money. But it looks like no one has even lived in the house for a while. And then he leads me out back to the guesthouse, but halfway there he stops and says, “Through there.” Like Brandt. “In seclusion.”

So I knock on the door and say, “Helloooo?” And it sounds like people are boning—I hear this fuh hah boom boom boom. And I’m knocking on the door, and I open it a little bit because it’s not shut, and it’s a woman on a bungee cord making body prints on the floor. It’s bizarre. She had paint all over the place and was butt naked—except for the little bungee-cord thing.

And then she stops bouncing there and says, “One moment, Mr. Abernathy, I’ll be right with you.” She put on a robe, and we sat down and had a business meeting. Bizarre. It never became anything.

Bums: So you hadn’t heard anything during Lebowski production about these stories serving as inspirations?

LA: No. I knew nothing about the movie whatsoever. All I knew is the Coen brothers had come out with a new movie and it had tanked. But somebody had said, “It’s funny and you should watch it.” Someone recommended it who had no idea of my involvement on any level.

So I’m sitting there watching this movie, and it starts to become eerily familiar. And I’m sitting there going, “Did I read this script at some point? Or worse yet, did they hire me to punch this thing up? Did I work for the Coen brothers and I don’t remember it?” Of course, I’m staring at the joint and I’m thinking, “Damn! I think I’m losing my mind!”

And I think finally, when they got to Little Larry Sellers’s house, I finally thought, “This is très fucked up. This is my life. My life is in a movie and I don’t know how.” And of course I got to thinking about it, and being a former detective I said, “This stinks of Exline.” So I called up Peter, which I actually think might be the last time I spoke to him, and asked him what the hell happened.

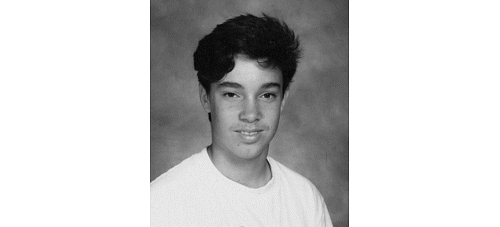

JAIK FREEMAN: The Real Little Larry

One of our biggest thrills in assembling this book was locating and interviewing the real Little Larry. As it turns out, he’s neither a brat nor a criminal. He’s a pretty funny, well-adjusted dude. Now thirty-two, Jaik followed his father, the famous writer Everett Freeman, into the film business. And until we called, he had no idea that the day in his living room when two strange men arrived with his homework in a baggie had been a pivotal inspiration for The Big Lebowski. Here is his story. All this took place in 1986–1987. He was in seventh grade at the time.

Bums: As we told you, we’ve actually spoken to the guys who came to your house that day.

Jaik Freeman: Right.

Bums: And got their version of the story.

JF: I’ve got some questions for you. I’ve got some questions about what actually happened that day. As opposed to what’s gone down in the movie.

Bums: Yeah, that’s what we want to get to the bottom of. But before you tell us that story, we’re curious what your reaction has been this week since we left you that phone message and first spoke with you. Was it your mom that we had left a message with initially?

JF: Yeah, that was my mother. My father—I know you asked for my father on the answer ing machine, but he passed away years ago, actually.

So, yeah, you know, I wasn’t too thrilled by the portrayal. Especially because I didn’t steal the car.

Bums: But what did your mom say to you about the phone message?

JF: Honestly, she just asked, “Do you know anything about this?” And I went over to the house, listened to the message, and I obviously had no idea what you were talking about. She didn’t either.

She had been in the room, she took the phone call from these guys, and then was there sitting next to my father, who was there in the room with us at the time—you know, smoking furiously—but she hon-estly didn’t really remember it. It was twenty years ago and it was right before my father passed away, and he was really ill at that time.

Bums: So when we talked with you initially and explained it to you, you had no idea that this incident had inspired this scene from the film?

JF: No, none at all. And I had you on speakerphone, and my girlfriend was sitting there, and you were describing the scene, and she was nodding her head furiously, like, “I know the scene! I know the scene!” and I’m thinking to myself, Well, that sounds familiar, but I don’t remember it from the movie.

Bums: Did you go out and rent the movie after that conversation?

JF: I did. I rented it over the weekend.

Bums: And you had seen it before, right?

JF: I had, but it had been so long ago, and I don’t really have much time these days to really hang out and watch TV or watch movies.

Bums: So you said it was twenty years ago?

JF: Yeah, I was twelve.

Bums: Do you remember what you were doing when your mom called you down when the doorbell rang?

JF: Well, I vaguely remember her saying, “Well, what’s going on?” And asking me if I’d stolen a car. And I just said, “No.” And she said, “Well, these guys are coming over.” And she is in panic mode at this point, or ready to kill me for something that I haven’t done.

And so the guy comes over, and I remember him walking through the door. The guy who was with him, I remember what he was wearing, but I don’t remember his face. He was in a white shirt, with a black or a dark tie and some slacks. You know, was he actually a private investigator, or was he just his friend pretending to be a private investigator?

Bums: No, he was actually a private investigator. The big guy. His name is Lew Abernathy, and he says hi, by the way. And “No hard feelings.”

JF: Lew Abernathy. Okay. I had no idea what to make of this guy, because—I mean, I knew who stole the car, and you’re going to hear about this—but I was just thinking, Well, why is he here? And why aren’t the police here? I mean, who is this guy? I’m twelve years old, and I’m feeling like, What am I dealing with here?

So that was my take on the guy, the guy that he brought over with him, the private investigator. And as for the guy who owned the car, he was just kind of sitting there with this scowl on his face the whole time, just kind of staring me down.

Bums: So do you remember anything about the briefcase?

JF: Okay, my father was confined to a hospital bed in the living room. Like I said, he was paralyzed on his left side and it was a hard time, and he died about four years after that. So he was in the hospital bed.

The couch was facing the bed, and they were on the couch. My mother was in a chair next to the couch, and I was situated in a chair at the base of the hospital bed, looking at them and my mother. It was kind of like in the round—kind of.

And I remember them asking me, “Did you steal this car?” And I said, “No.” [flatly and finally, like a stonewalling teenager].

So he drops his briefcase on the table, and he says, “Are you sure?”

And I said, “Yeah.”

And as I recall, he opened up the briefcase and said, “Is this your homework?” That part was exactly like in the movie. It was in this little plastic wrapper.

And so I say, “Yeah, that’s my homework.” [flippantly]

And it was a math book, not history—if that makes any difference. It was my algebra book. And my algebra book had been left in the car. And my homework was obviously left in the book. And that’s basically how they got me.

So I said, “Yeah, that’s my homework.”

And then they said, “Well, there were McDonald’s wrappers in the car, and with that kind of greasy stuff, there’ll be fingerprints everywhere.”

And I was like, “Great! Fingerprint the car!”

So they are sitting there kind of scowling at me, and finally I remember saying to them, “Look, I don’t know either of you guys, and I’m not going to say anything else. If you take me down to the police station, I’d be more than happy to file a police report. But I’m not going to say anything else here.”

And after that, there was nothing else that came out. Honestly, I figured that what happened was that they did go down, they did fingerprint the car, they didn’t find my fingerprints, and that’s why I never heard from them again.

The way the car got stolen, I guess, is Harry Jones.* Harry Jones was a friend of mine at that point. He was a couple of years older than me—most of my friends were a couple years older than me. My best friend lived directly behind me on the other side of the block, and he was two years older than me. And I kinda hung out with all the kids in his grade. So, you know, I was twelve years old, hanging out with all the older kids.

So Harry Jones had stolen the car. And he actually a little later on got busted for a string of stolen cars. If I remember correctly, this guy’s car was a Toyota. I think it was a Corolla or something. Because Harry had told everybody that you could get into these cars very easily simply with a screwdriver and a pair of vise grips. All you had to do was break the window, and then you could just slam the screwdriver into the ignition, crack the ignition. So that was why, I guess, his car got targeted.

Harry had borrowed my math book. He’d said, “I need to borrow your math book,” and I’d just said, “Okay. Sure, no problem.” I’d done my homework. And it didn’t really dawn on me why he’d want to borrow mine, because—I thought about this later on—he was in a higher grade than me, so if he wanted to show up in class with a book … whatever.

So I’d loaned him my book and he, I guess, had left it in the car. And go figure. I’m the guy that gets immortalized as a dunce in the movie.

Bums: Would you say that you were more annoyed and pissed, or were you scared of these people—this crazy dude waving this homework in your face?

JF: I wasn’t scared of him. At that point, I was scared because what do your parents think when this happens? And you honestly haven’t done it. Of all the fuck-ups that I’ve made in my life, you know, like, “I didn’t do this.”

Like I said, my father was sick at that time, so that was really more my concern. Who are these guys to come in here waving this shit around in my face when they obviously haven’t done their fucking homework?

Bums: When you saw the movie, you didn’t have any sort of air of familiarity—it didn’t seem eerily familiar or anything?

JF: Oh, yeah, definitely when I saw it again. I mean obviously they pretty substantially exaggerated what my father was like. It was like he was hooked up to some respirator in a 1950s sci-fi machine, you know. And there was no maid, by the way.

Bums: No Pilar. Now, they claim that your dad was actually reading some screenplays. Was he a screenwriter?

JF: Oh, yeah. That’s also true. My father was a writer-producer for years. Sam Goldwyn brought him out to Hollywood in the thirties or something—I think it was ’37, or it might be later than that—and he worked in TV, he worked in film. Got two Oscar nods. Everett Freeman.

Bums: Now, did this meeting have an impact on you? Did you straighten up?

JF: [offended] Did this meeting have any effect on me? Was I scared straight by some joker and a guy pretending to be a private investigator? Or a private investigator pretending to be someone important?

No. That didn’t scare me straight. I mean, after that it was teenage rebellion. My father died and it was teenage rebellion, and I acted out for a number of years and slowly but surely straightened myself out, and now I make the world a better place. That’s a joke, by the way.

Bums: Do you feel like maybe the Coen brothers owe you anything?

JF: They owe me big. And they don’t even know it yet.

The Stranger Says …

“Good night, sweet prince.” On August 7, 2002, Hollywood Star Lanes in Los Angeles, where much of the film was shot, closed to make way for an elementary school.

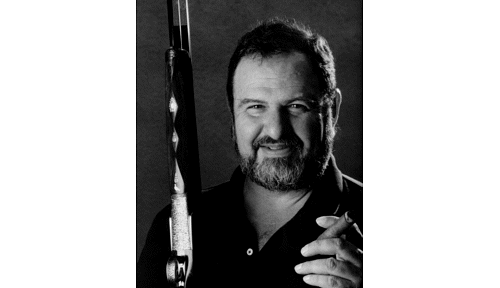

JOHN MILIUS: An Inspiration for Walter. He’s Not Housebroken.

The character of Walter Sobchak was largely based on Hollywood legend John Milius. Milius wrote Apocalypse Now and wrote and directed Big Wednesday, Conan the Barbarian, and Red Dawn, among many, many others. Along with his film credits, he’s known throughout Hollywood as a maverick, a militarist, and a political conservative in a town famous for its left-leaning politics. (As he himself puts it, “I’m not housebroken.”) For many years a large photograph of an atom bomb exploding over the Bikini Islands occupied the wall behind his desk. And let’s also not forget—let’s not forget, Dude—that he is one of the founders of a little enterprise called the Ultimate Fighting Championship. Not exactly a lightweight.

John Milius: Everybody loves The Big Lebowski. My kids love that movie. They all say, “That’s our father, there! That’s him!” They like that better than any of my movies.

Bums: How did you meet the Coen brothers?

JM: Well, I saw their movies. And I’m not positive, but I think they just called me up out of the blue and they wanted me to act in a movie for them.

They wanted me to be the head of the studio in Barton Fink. And the guy got an Oscar nomination for doing that, Michael Lerner. And I read it, and I remember I said, “This is real acting!” It’s like paragraphs of lines and stuff like this, and I said, “You know, I can’t do this. I’ll crack on the day. I’ll get up there and I’ll just freeze up. I can walk by and smirk or say a couple of words, but I can’t do this, you know? This is the real stuff!” So they were very disappointed that I didn’t do that.

Bums: At what point did you realize that you were part of the inspiration for Walter?

JM: Well, they never told me. But people who saw the movie said, “That’s you!” And of course I looked at the movie, and I said, “Yes, it is!” I especially like where Walter bites the guy’s ear off.

The first time I saw the movie, I just laughed and laughed. Most of the time when people do an imitation of you, you’re embarrassed and it’s awful. You say, “Oh, I don’t really sound like that. I’m not really like this.” This is one where I just sat there and cracked up. It was like the best kind of roast.

Bums: So what character traits would you say that you and Walter have in common?

JM: Well, I don’t bowl. Like he says, “I don’t roll on Shabbos!” I just love that whole idea of that guy, you know, that he’s Jewish when it’s convenient. He’s constantly bringing the Vietnam War into anything. And the ending is so ludicrous. They’re dumping the ashes into the ocean, and he starts talking about those who were lost at Khe Sanh and such and such. And the Dude says, “What the fuck does that have to do with anything?”

And he really didn’t have an answer. You know, like, “Why not? Why doesn’t Vietnam have anything to do with it? It has to do with everything!” What I love about the character is he has such great enthusiasm. The whole movie is so good. The Dude is just a wonderful character too.

There are certain movies that, as time goes on, they acquire more and more weight and importance, and that’s one of them. And the movies that people think are very important at the time often are not important at all as time goes on.

Bums: Why do you think that is? What is it about this movie?

JM: I don’t know. It really is something you remember, and it makes you feel good. It just has something that touches you, you know, that is just outrageous. It’s funny because it really has a greater timelessness than their other movies, doesn’t it? And they’ve made some good movies.

Bums: Off the top of your head, do you have a favorite scene from the movie?

JM: Oh, I don’t know. Like I said, I love the final action confrontation between those guys. Because you’re waiting for that the whole movie. And it really makes you want to cheer, you know? There’s just something about it, it just really makes you feel good. You want to cheer. And that doesn’t work usually in movies.

But there are movies that have that effect that are kind of plain. When I talk about a comedy, I always talk about a Caddyshack-grade comedy, because most comedies aren’t. Most comedies, a couple of years later you say, “That wasn’t so funny.” But some of these movies gather impetus and weight.

And you never know what that’s going to be. Viva Las Vegas has that quality to it. If you want to have a good night at your big-screen TV, get Viva Las Vegas. Elvis, Ann-Margaret, in Las Vegas. Hard to beat.

But there are a lot of films that are so important and such great films that don’t mean a thing later, you know? Like most of the Star Wars movies, to me, can be used for interrogational purposes. I mean, this is one of only a handful of modern movies that are worthy of a book.

Bums: Well, we’d also like to switch gears from the movie and ask you a few things about yourself. What’s it like to be a conservative in Hollywood?

JM: You know, I’m not a standard conservative. See, I like to call myself a Zen anarchist.

Bums: What does that mean?

JM: It means I can do whatever I want! Right now I’m very angry with the Republican Party because of their support of corporate greed. Which I think is even worse than terrorism. And you start talking about these guys like Ken Lay and Skilling and I turn into a Maoist, you know? I want show trials with tumbrels with these guys in them and signs around their necks. Public executions, public denunciations, things like that. Where they are actually shot and charged for the bullets—their families are charged for the bullets.

I mean, see, I really actually believe that stuff. I just hate it. But at the same time I’m a militarist, you know? So I don’t really make a lot of sense. I often think about when David Bowie was once told by a journalist, “You’ve contradicted yourself several times, Mr. Bowie.” And he said, “Well, I’m a rock star.” That’s how I look at it.

But being a conservative—I’m everything that they don’t like in Hollywood. An agent once said that the problem with Hollywood is that there are still rattlesnakes in Bel Air and Milius is there. They blacklisted me and cut me out of the last ten years or fifteen years. So it’s been pretty rough. But I’m amazed how much I actually got done. And I’m still at large, still doing stuff. I did Rome. And I’m doing stuff right now.

So the fact that I’m still out there, that I’ve watched all the studio executives who snubbed me fall into decay and be savagely attacked by their own friends—I often like to say, “I’m the Yeti.” That was my surfing name. They haven’t caught me yet!

Bums: How did you become a militarist? We read that you weren’t able to serve in the military, although you wanted to.

JM: Yeah, I was really, really disgusted with my life and myself. And I probably have chafed at that ever since. I probably feel that I didn’t get my chance to get killed in Vietnam. I mean, it’s really stupid to take that attitude, but still. And so I just felt very supportive of the military and did everything I did to support the military and go off to whatever wars we had. But I haven’t been to Baghdad. I’m too slow now. I’d probably get somebody killed.

Bums: Now, is it true that you were one of the original founders of the Ultimate Fighting Championship?

JM: Absolutely. I remember when I did that, and they had the second one, and Harrison Ford—we were making Clear and Present Danger then—he said, “Do you know what you brought about? You’ve brought about gladiatorial combat!” And I said, “Right on!”

And it’s gotten bigger than ever. I think it’s going to overtake boxing. Because I think people really want that. I think people really want to get down to being honest about it, you know? On YouTube they watch the Iraqi War. They say, “Why do I want to go see a war movie when I can see people blown up?”

Our society is really changing. We need stronger dope, you know what I mean? We require a bigger thrill. The idea of having boxing—it’s been there, it’s happened. UFC is gladiatorial, and people want that. You watch, it’ll change.

Bums: What did the Coens see in you that they were able to transform into Walter?

JM: Well, I’m not your normal, run-of-the-mill character out there, you know? I have some pretty crazy attitudes. And I also—I’m not completely housebroken. They sort of liked that. The thing that’s interesting about Hollywood today is that it’s a town of lots of people working who are motivated by fear. And there is this terrible cloud of fear that hangs over everything. Everything is done with fear. The whole purpose and structure is about fear. You’re afraid you’ll get fired if you do something wrong. You make a movie that isn’t good enough, doesn’t make enough money on opening weekend, you’ll never make another movie. This kind of thing. And so people like me don’t exist.

Bums: Too dangerous?

JM: Yeah, the only guy who is kind of like me is Quentin Tarantino. Whereas people like me were quite common in the old Hollywood. Mitchum was that way. John Huston was that way. Mitchum did whatever he wanted. People just accepted him because he was Mitchum. Steve McQueen was that way. Steve McQueen was not housebroken. But he didn’t make a big deal of it, you know? He was just that way.

Peckinpah was probably the most extreme. But one of the things about Peckinpah that was really great was that he believed in what he was doing. He wasn’t scared of anything. He was a zealot, you know? And so you had to have respect for him. He didn’t play the game by their rules. He didn’t sit there and say, “Okay, I’m going to be really clever and smart.” There was nothing clever at all about them. They just did what they did.

That is gone from our society. And really we need that. We need that kind of thing.

*In 2003, the Coen brothers graciously allowed us to borrow the prop marmot that they used in the bathtub scene to display at the Third Annual Lebowski Fest in Louisville, Kentucky, in exchange for two Achiever T-shirts and a poster. The fake marmot was mounted inside a glass case with an engraved plaque that read MARMOT ON A STICK, and a PVC tube extending from its tiny rodentlike rear with a drill attachment on the end. Apparently the drill attachment was used to “spin” the fake animal in the bathtub water.

* This name and others in the book have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals. This is a private residence, man!