The assumptions you don’t know you’re making will only get you into trouble and confusion.

—Douglas Adams

“I’d like you to think of something that you worry about often,” says Alex Temple-McCune, a baby-faced PhD student with the air of a much older, kindly doctor.

“Oh, that's easy. My son running into the road outside my house,” I reply. Alex stares at me, impassive. “He's five,” I add, by way of explanation. “It's a very busy road.”

He nods, slowly. “Okay, I am going to leave the room for five minutes, and I’d like you to worry about that for the whole time I am gone. Think about it in as much detail as you can, and try not to think about anything else.”

Oh God.

“This is going to be horrible!” I plead, feeling my eyes widen as Alex gets up to leave. He hesitates at the door but goes out anyway, leaving me alone in a sparse, white, windowless room to think, in horrifying detail, about the worst thing that could happen in my life.

I am here at Oxford University to take part in a study into the cognitive basis of worrying, in the lab of Professor Elaine Fox. I’ve taken all the necessary screening tests to confirm that I am, indeed, a frequent worrier—and over the next two weeks the plan is to try and rectify that with a training course, designed to change the way the brain deals with stress.

After my success in Boston, changing this particular feature of my brain is very much next on the list. It seems to be one of the areas where there is pretty good evidence that you can, with a bit of effort, make real changes to your brain. There has been a good fifteen years’ worth of work in this area because worrying too much is not only bad for sustaining focus, but it is also seriously bad for your health.

Here's a statistic that worriers everywhere will enjoy: persistent worrying—even low-level fretting that doesn’t qualify as a proper anxiety disorder—makes you 29 percent more likely to die of a heart attack and 41 percent more likely to die of cancer. In fact, according to the study of eight thousand people that generated these figures, worrying a lot makes you more likely to die of anything, and the bigger the daily dose of stress, the greater the risk.1

I can’t help thinking that if my friend Jolyon hadn’t spent his twenties and thirties enjoying a totally debauched lifestyle, he’d probably live forever. Because Jolyon never, ever, worries. While I have been getting my knickers in a twist over various incarnations of this book, he has formed a company, launched two successful brands, and made several million pounds. He named the company “Gusto” for good reason—this is a man who never does anything by halves and couldn’t care less what anyone thinks about him while he's doing it. You could say that he doesn’t even worry when he probably should: he launched Gusto while his partner was pregnant with their first child, giving up a highly paid, steady job that he was very good at, and putting all of their financial security on the line to do so. If it failed, as he cheerfully told me most businesses do, they would find themselves broke, with a newborn and nowhere to live. It was touch and go during the first few months, but he never really believed that it wouldn’t work. “I lost thirty thousand pounds on one day when I first started,” he told me. “It just made me more determined to make it back.”

It's the same story you hear over and over again about plucky overachievers: they don’t get bogged down by what could go wrong or what just did go wrong; they just dig in and get on with it. It must be a really nice way to live.

Then there is the fact that anxiety is really bad for pretty much any kind of thinking. It not only narrows focus, but it reduces impulse control and robs the brain of processing power that could better be used for other things. Over time, it has been found to shrink the hippocampus, a crucial brain area for memory. There has been some evidence unearthed recently that having an anxious temperament has some benefits, such as making a person more empathic and quicker to respond in a crisis—but overall it's not a great state to be in if you want to get the best out of your brain.

Some scientists—including Elaine Fox and her team at Oxford—think that differences between the likes of Jolyon and the likes of me come down to basic differences in the way our brains process information about the world around us. In her research, and in her 2012 book Rainy Brain, Sunny Brain, Fox argues that it all comes down to the balance between two of the most ancient and powerful circuits in the brain—one responsible for seeking out danger and the other for spotting potential rewards—and how well connected they are to the newer, thinking, bits of the brain. A skew to one way or the other is known as a cognitive bias—in other words, an assumption we don’t know we are making. The direction and strength of these cognitive biases, Fox says, make us who we are—whether that is a driven and confident risk-taker like Jolyon, or more of a reticent worrier like me.

So again it all seems to come down to what we do with our limited budget of attention. Unlike the deliberate focus I was working on in Boston, though, this is an automatic kind of attention that operates within milliseconds, directing your focus to whichever parts of your surroundings seem particularly important. Crucially, all of this happens before we are consciously aware of noticing anything, and that means that, although we don’t realize it, our conscious mind is constantly being fed a fundamentally skewed view of the world. This makes it particularly challenging to control. How can you change something that you’re not even aware you are doing?

A negative cognitive bias might not be very good for you, but it undoubtedly evolved for good reason: it came in handy in the days when we were at the mercy of large, toothy predators and men with clubs because it drastically cuts down processing time in the brain when we need to move fast. The downside is that the unconscious nature of these biases means that we live under the illusion that our own impression of the world—whether it is fundamentally safe or to be fretted about at every opportunity—is a totally accurate window on reality, when it is actually anything but. And that means that if you want to change your outlook on life—say, if you don’t like the idea of hurtling, gray-haired and haggard, to an early grave—it isn’t an easy thing to do.

On the plus side, the laws of neuroplasticity aren’t swayed by a little thing like the border between unconscious and conscious processing, and Fox and others are working on finding ways to nudge troublesome cognitive biases back in a more positive direction. It sounds like something that is definitely worth a try, especially because some research suggests that all you need to do to retrain your cognitive bias toward a rosy view of life is to play a computer game for a few minutes every day.

It's a controversial area of research, and not everyone is convinced that it works, but it resonates with me partly because it treats an anxious temperament not as a fundamental part of who you are but as a kind of system error in the brain. And I get that because if I’m really honest about it, my main problem with all this worrying is that it really isn’t me. Outwardly, I’m quite a risk-taker (freelance journalism isn’t for softies), and most people would probably describe me as mostly upbeat. The other day, another mother at the school gate described me as a “super mum,” and I don’t even think she was being sarcastic. So clearly I give off the impression that I have things pretty much under control. Only I know about all of the negative chuntering, worrying, and general unease that goes on under the surface, and that, frankly, gets on my nerves.

Earlier, in Boston (in chapter one), I found out that I score highly on a measure of trait anxiety (also known as neuroticism, which seems a bit harsh), and research has shown that people like me, who score high on this measure, tend to have a negative cognitive bias, which we use to subconsciously scan the environment for threats at all times. We are also more likely to get stuck in threat-obsessing mode, assessing and reassessing a situation in pessimistic terms and getting progressively more worried. And yes, I do both of these things. The first of them, threat readiness, is pretty understandable, I think. When I was nineteen, my father was killed in a car accident. In the twenty-odd years since then, I have perfected a kind of 360-degree, all-seeing eye for danger—especially the randomly occurring kind that could take a loved one away from me at any moment.

My age when my father died might explain why this harsh life lesson stuck fast in my brain. It has long been suspected that the adolescent brain is particularly plastic. This, after all, is a time when growing independence relies on being able to learn from your mistakes. Research has shown that the adolescent brain not only stores memories more vividly than adults, but it is also particularly sensitive to stress, taking longer to recover from emotional setbacks.2 These two factors together explain perfectly why unpredictable danger would have been writ large in my brain from there on in, but even in my most angst-ridden moments I know that the panic I feel is wildly out of proportion to any real threat. Is it helpful that if my husband is away on business and doesn’t text me the second I expect his plane to land I start checking the news for air disasters? Is it good for my son that I jump out of my skin when he goes anywhere near a road, or even looks in the general direction of a hanging window-blind cord? And then I worry that his mother jumping in the air all the time actually makes it more likely that he’ll have some kind of tragic accident—what if I accidentally knock him into the road while rushing to keep him from the edge?

Then there's the way that I assume the worst based on very little evidence. In the month before I went to Oxford, I sent Elaine Fox several emails explaining this whole project and asking if she would like to be involved in my mission to rewire my brain. I sent her the blurb for the book and a link to one of my previous articles, which was along similar lines to what I was hoping to do with her. And…nothing.

The logical explanation is that she was busy. But, in my head, it was much more likely that a) she thinks I’m some flake who can be ignored because the book sounds like trash and no one will read it anyway, b) she has read some of my previous articles and thinks I am the worst science journalist in the world, c) she is so disdainful of the whole thing that she has circulated my email to her fellow researchers and is now laughing heartily with them about this stupid journalist who won’t leave her alone.

And how did I deal with this? Well, I put her number in my phone and chickened out twice about calling her (because she obviously doesn’t want to talk to me). I followed her on Twitter, just in case she's tweeting about the latest offering from the neuro-bollocks school of science writing. And I went around in endless emotional circles ranging from anger (it's a bit rude to just ignore my messages!), to indignant imaginary conversations where I justify my credentials to her, to practicing how cool I would be about it when she told me to get lost. Seriously. It was starting to feel like the time I phoned a boy in the year above me at school (also called Fox, funnily enough) to ask him out. I did it in the end but not before practically giving myself a coronary. (He had a girlfriend, but we became good friends and briefly dated a few years later….)

And guess what? When I finally did call Elaine Fox, she was lovely. She apologized for not getting back to me and explained that she had been buried under an awful deadline for weeks and was still up to her eyeballs in it, preparing to move her entire lab over the summer. But she thought my project sounded fascinating and agreed to talk properly in a week or so. So what was the point of all that stressing? Weeks spent swirling around in an emotional whirlpool when I could have been doing something useful, like writing the introduction to this book.

This is the kind of thing I do to myself all the time, and, while it has never really stopped me from pursuing what I want in life, it would be a lot more convenient to bypass the terror and self-flagellation and just get on with it. And, let's face it, it's ridiculous to get uptight about contacting a person who works on treatments for anxiety.

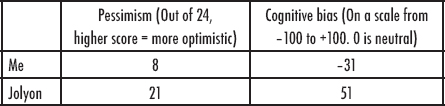

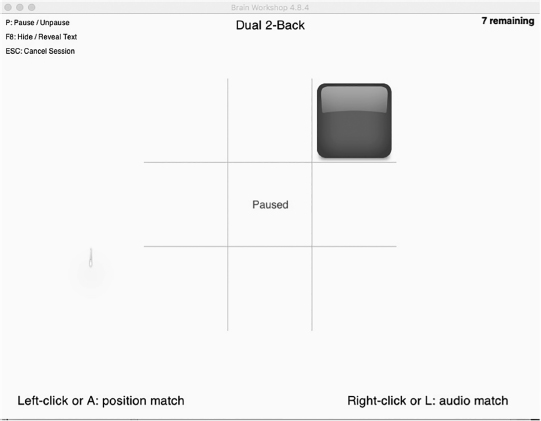

Of course, it was possible that my neurotic tendencies would have nothing to do with a wonky cognitive bias, so while I was waiting for her to reply, I headed to Elaine Fox's website where there are two tests—one for cognitive bias and a questionnaire to measure a tendency toward optimism or pessimism.3 Just for fun, I asked Jolyon to do it too. Our scores are below.

Figure 2.1. Optimism/pessimism scores and cognitive bias, as measured on www.rainybrainsunnybrain.com.

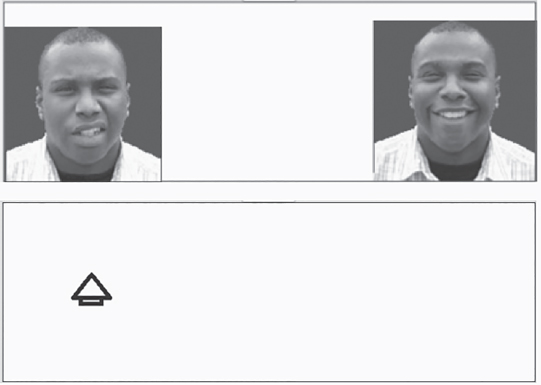

Psychologists measure cognitive biases using a computer-based puzzle called a “dot-probe task.” First, a cross appears in the center of the screen, to give you something to look at. Then, two images flash up for five hundred milliseconds, followed swiftly by a target (which can be anything—an arrow, a dot, whatever). Your job is to press a button on the left or right, depending on where the target (aka probe) has shown up. Research has shown not only that a) people with an anxious temperament are quicker to spot targets that appear on the same side as the angry face (a negative bias) but also that b) people with a negative bias are more prone to anxiety disorders and depression.4

Figure 2.2. Dot-probe task screens 2 (top) and 3. (Courtesy of Mark Baldwin, McGill University)

A little bit of background research later and I have the proof: Jolyon is as strange as I am. According to surveys of large numbers of people, an average score on the optimism/pessimism test is 15 out of 24, meaning that the average person is generally slightly optimistic. Jolyon and I are each six points away from the average but in opposite directions. He is unusually positive (hence the risky financial deals) while I am an almost perfect-scoring pessimist.

Which ties in nicely with the direction of our unconscious cognitive biases. A score of –31 means that I press a button thirty-one milliseconds faster when it follows an angry face than when it follows a smiley one. Jolyon, on the other hand, is fifty-one milliseconds faster to spot the target when it comes after a happy face. His brain automatically seeks out the good side of life—which probably explains his unusually high levels of optimism.

If all it takes to put things right is a quick bit of computer-based training, then it shouldn’t matter how we got to be so different—but I must admit I’m curious. A glance around my close relatives makes me suspect that at least some of my neurotic tendencies might be inherited. On one side of my family it's considered unusual if you’re not anxious, prone to depression, or emotionally a bit volatile. A quick head count of my aunts, uncles, and cousins on that side of the family reveals that while the average number of people with emotional issues in the United Kingdom is one in every four, our family has roughly twice as many.5

Elaine says she’d be happy to put me into her next study on the genetics of worry, but they probably won’t be ready to do the tests for at least another year. As a backup, she puts me in touch with the lab that does the analysis for her studies. She warns me that it’ll be expensive (at least £500, or over six hundred US dollars), but it might be possible as a one-off. It's my only hope because while some medical insurance companies in the United States will do the test under certain circumstances, commercial gene-testing companies like 23andMe—which offer off-the-shelf tests for risk genes, for everything from Alzheimer's to male pattern baldness—don’t offer it, at least not yet.

As it happens, when I contact the lab, they are happy to help and can even chuck a few more samples in for me at no extra cost. I get a testing kit sent to Jolyon, and then we swab our cheeks, pop them in the post to the lab, and wait with bated breath to see what comes back. After several weeks of back and forth between Jolyon and the lab, where he manages to avoid getting any DNA on his first set of swabs and the second batch gets lost in the mail—and I start to wonder how he runs a successful business at all—we finally get the results. And the verdict is…not at all what I expected.

THE WORRIER/WARRIOR GENE

Let's not get carried away—there are most definitely lots of genes that contribute to something as complex as your outlook on life. But the serotonin transporter gene is particularly interesting because of the way that it affects the kind of implicit learning that underpins unconscious biases.

The serotonin transporter gene makes proteins that mop up one of the brain's chemical messengers after they have been used to send a message between neurons, and recycles as much as possible, to be used again.

Everyone has two copies (aka alleles) of this gene, and it comes in two versions: one short (the S-version) and one long (the L-version). Confusingly, there are also two versions of the L-version (LA and LG), and LG acts almost exactly like the S-version.

This matters because the S and LG versions contain less DNA, and so they can’t produce as many transporter proteins. This leaves more serotonin hanging around between neurons, meaning there is less serotonin in the actual neuron to send more messages.

Each of us has one of the following versions of the serotonin transporter gene: SS (short), SLA (medium), SLG (short), LALA (long), or LGLG (short), with SL being the most common and SS the rarest, at least in a UK population (it varies around the world).6

People with at least one S or LG allele have been found to have a more reactive amygdala (involved in danger detection) than others.7 They are also more likely to have a negative cognitive bias, to have a higher score on standardized anxiety tests, and to be at higher risk of depression. Other studies have found that people with the long version are more likely to have a positive bias.

But while it sounds like it's “case closed” for the “worry gene,” it turns out to be not quite as simple as that. While some studies have found a link between the short allele and an anxious temperament, others have found the opposite. A long-term study led by Avshalom Caspi and Terrie Moffitt in 2003 provided a crucial clue as to why.8 They looked at not only genetics but also at the number of stressful events a person had been exposed to. And they found that people with the short version were indeed more likely to become anxious or depressed, but only if they had also experienced at least one stressful life event (divorce, abuse, death of a loved one, etc.). Without life stress, they were actually less likely to become depressed than people with the long-gene type. So the same gene can be either a “worrier gene” or a “warrior gene” depending on what happens to you along the way.

One possible explanation for this is that having the S-version gives a person a kind of super-plasticity brain, which learns and retains the lessons life throws at it unusually well. The downside is that if you learn from stressful experiences, your brain is more likely to conclude that there is a lot to fear in life and that the world is generally a dangerous place. On the upside, it quickly learns the opposite, too, if given half a chance.

Sure enough, in Elaine Fox's lab, people with the short version were quicker to develop not only negative biases but positive biases too: “If a few bad events happen, you are more likely to develop a bias and then that gets reinforced. But by the same token, if the positive biases start developing, the people with that same genotype will be more likely to develop a positive mind-set,” she told me.

So, the current consensus is that people with shorter versions of the serotonin transporter gene seem to be more vulnerable to the long-term effects of stress, but are also more likely to learn from life experience if it happens to be good. Given the way my brain has learned from my own stressful life events (my parents’ divorce when I was five and my father's death when I was in my late teens), I would have bet money on me being a carrier of the short version of the gene. Jolyon, I wasn’t sure about—but guessed that he was probably a super-resilient long-version carrier. We joked that if we were both short-gene carriers, it would be fantastic news for his parents and a bit of a kick in the teeth for mine.

In fact, the genetic test revealed that he is indeed an SS carrier—born with a brain that is set up to learn from life experience unusually well. The way he describes his early life suggests he got pretty lucky: no emotional upheaval, nobody died, and he wasn’t bullied or abused in any way. This combination of genetics and experience seems to have made him super resilient to life's ups and downs, highly resistant to stress, and with an optimistic view on life.

Me, I’m among the 50 percent or so that has one copy of the short version of the gene and one copy of the standard long version. Which basically means that I have a moderately sensitive brain: not especially resilient but not the most sensitive on the planet either.

This might be my negative bias talking, but it seems to me that it might give me the worst of all worlds. With one copy of the short type, it does mean that my genes have made it more likely that life stress will turn into a potentially problematic negative bias. But, not having the most plastic brain possible, it might not be an easy ride to change it, either.

THE WAY OF THE WORRIER

At this point, it seems sensible to look at what happens in the brain to generate an anxious thought, to get an idea of what I would be changing, if I were to manage to turn things around. As it happens, this is one area where the circuitry is fairly well understood—at least in as much as anyone understands what a thought actually is. I once asked Geraint Rees, a prominent neuroscientist at University College London, to explain what happens in the brain to make a thought, and, because he is a prominent neuroscientist, I expected a concrete answer. What he actually said was, “A thought is a mental state. It is widely believed that mental states (things in the mind) correlate with neural states (things in the brain), but the mapping between the two is not well known.”

So even top neuroscientists don’t know how brain activity turns into conscious thoughts, anxious or otherwise. The tagline on Geraint Rees's lab website puts this rather nicely, I think, with a quote borrowed from Einstein (attributed): “If we knew what we were doing, it wouldn’t be called research, would it?”

But this we do know: for us to notice the thing to be feared at all, it has to stimulate one of our senses. Sensory information is constantly being passed to the thalamus, which sits in the middle of the brain and acts as a switchboard cum relay center between the senses, cortex, and other important areas like the amygdala and the hippocampus (which shunts things in and out of memory).

If there is anything around that has previously been marked as “dangerous,” it sends the information quick smart to the amygdala, the brain's burglar alarm, which snaps attention to it while readying the body for “fight, flight, or freeze” (racing heart, sweating palms, and so on). It also notifies the cortex (the thinking bit), which sets about making sense of the situation, and generates the conscious feeling of fear.

Joseph LeDoux, a neuroscientist at New York University, was among the first to describe this basic circuitry, and since then, an overactive amygdala has become the default popular explanation for everything from panic attacks to feeling a bit stressed out. It has never really seemed to explain my experience of being a chronic worrier, at least not for all forms of worrying. It probably accounts for the sudden tension I feel when crossing the road with my son, but when I’m fretting over something—like whether my work is up to scratch or whether the thing I said earlier made me come across as a bit weird—I don’t get a surge of adrenaline and a racing heart. It's very much a slow burn, thinking-based, self-torture kind of reaction, not a primal, physical, need-to-get-out-of-here-right-now kind of feeling.

It turns out that LeDoux now spends a lot of his time trying to explain the subtle distinction between fear and anxiety—most recently in his book Anxious. He says that these are two different, although closely related, emotions and each has a slightly different bit of brain circuitry.9 Fear—the sweaty palm bit—is a physical reaction to a threat that is happening right now, in front of you, and that might kill you if you don’t fight, run away, or hide. The emotion of fear comes later, once the slower thinking bit has come online. Anxiety and worry, on the other hand, are less to do with reacting to, or making sense of, a threat you can see but are more to do with a feeling of uncertainty about if and when something bad will happen and whether you are up to the challenge of dealing with it if it does.

Experiments have shown that damage to the amygdala doesn’t prevent this kind of self-torture anxiety from happening. Instead, another brain area—the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST)—is in charge of processing uncertainty.10 The key difference between them is where they get their information from. While the amygdala takes information mainly from the senses, to process what is out there in the world, the BNST gets more of its information from brain areas involved in memory and other types of cognitive processing, which means that it is more than capable of making a drama out of something that is entirely in your own head.

The BNST also seems to be the driver of hyper-vigilant threat monitoring: the keeping watch for anything that might, possibly, go horribly wrong. It does, though, put the brain in a state to react quickly if anything does happen. So the fact that I can freak out about my young son being near roads, even when he is safely tucked up in bed, should mean that I will react in super-quick time if anything actually happens. The downside is that I expend a lot of energy worrying about something that might never happen and which my lightning-fast amygdala could probably take care of anyway if it did.

As it happens, the amygdala and the BNST are both connected to pretty much the same areas of the brain—most importantly to the prefrontal cortex, which ultimately makes the decision about whether to escalate or calm down. The subjective feeling of anxiety or calm depends on which part of the circuit is most active at any point. Electrical activity is always flowing between the two, but depending on which is shouting the loudest at any one point, we will either feel in control of the situation or not.

If I want to take control of my worrying habit, then, I need to either reduce the number of (real or imagined) threats that get the amygdala and BNST going in the first place, and then use my thinking brain better to get out of the worry hole—or, preferably, both.

Gaining more control of the prefrontal cortex sounds familiar. But if Elaine Fox is right, there is a stage before this one that needs to be addressed: namely, the unconscious biases that are giving my prefrontal cortex more to do than is strictly necessary.

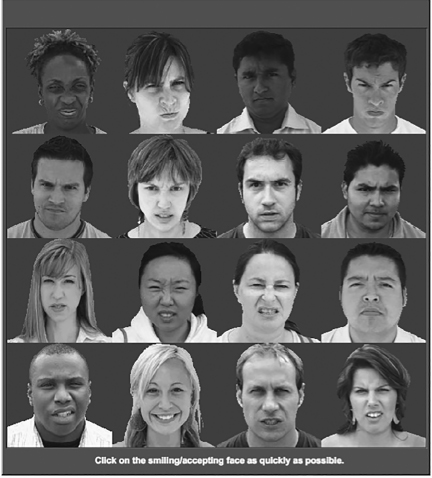

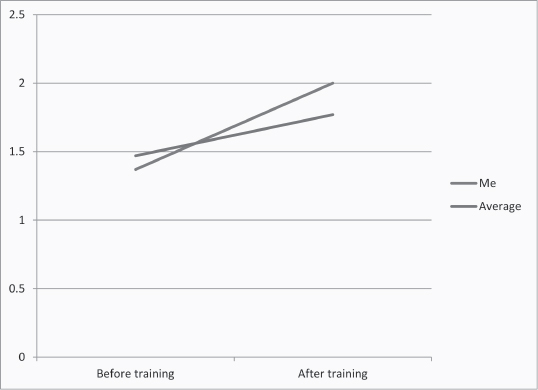

A trawl through the work of cognitive scientists working in this area reveals that there are three options. One is to use cognitive-bias modification training to train my attentional system to seek out positive things in an environment rather than negative ones. The most common approach to changing those biases involves flashing up a group of faces—most of them angry, and only one happy face—and asking people to click on the happy one as fast as they can (see figure 2.3).11

Figure 2.3. Cognitive-bias training. (Courtesy of Mark Baldwin, McGill University)

According to the people at the Baldwin Social Cognition Lab at McGill University who designed the task, the idea is, “Each time you drag your attention away from one of the frowning faces in the game in order to find a smiling, accepting face, this helps to build a mental habit. After a hundred trials or more the habit can become automatic…the mental habit generalizes beyond the visual domain of disengaging from frowning faces, to apply to disengaging from thoughts and worries.”12

Another option, based more on the prefrontal cortex (that part of the brain above the eyebrows that keeps the more automatic impulses under control) is a different kind of cognitive-bias modification but one that is focused on practicing changing a negative interpretation of a situation. This generally comes in the form of audio of an imaginary scenario, after which you have to decide if everything is going to be okay or not. (You only get a point if you answer with a cheery “yes!”). Being forced to be positive over and over again is also meant to create a mental habit that gradually becomes ingrained in the brain's wiring, blood vessel network, and so on.

Another option is to undergo working-memory training. Leaving aside the controversy over whether working-memory training does anything at all (that one is still being thrashed out), there are a few early studies that seem to suggest that training working memory might help to reduce anxiety—on the basis that improving working memory might provide more mental space to talk yourself out of a worry hole. Of course, it might backfire and provide more mental workspace to worry about everything that might go wrong.

Then there's meditation—which, for me, is a work in progress. If I’m totally honest, I’m really hoping that the answer to my brain blips isn’t going to be meditation; I’m really not sure I can stick to a sitting quietly habit for very long.

As it happened, my first bite of the cognitive brain-training cherry came not from Elaine Fox's group down the road in Oxford but from Ghent University in Belgium, where neuroscientist Ernst Koster is doing very similar work as Fox. While I am waiting for Fox to get back to me—and fretting about not having very much to write about yet—I drop Koster a line to see if he might be able to help.

A couple of days later, we chat over Skype and he puts my fears to rest. Yes, he tells me, he could send me links to the online training they use in their studies, and he’d be happy to assess my anxiety levels before and after. It all sounds easy enough—and I wouldn’t even have to leave my sofa. But then he tells me about the experiments they’ve been doing with eye-tracking technology: measuring attentional biases by monitoring where your eyes flick to, before you even realize they have moved. Apparently, Koster and his team have had some interesting results with this, but it can only be done in the lab—which would mean a trip to Ghent. I’m intrigued, and I’ve never been to Belgium….

Koster promised to check the lab schedule and let me know when there would be some free time over the next few weeks. A few days later, I find myself on a Eurostar train to Belgium: he did get back to me as promised, but rather than, as I expected, setting a date for some leisurely time over the next month or so, I was informed that there was a rare gap in the lab schedule in just two days, and if it wasn’t too short notice—and if I could get myself to Ghent—he’d be happy to put me through my paces.

It kind of was too short notice, but as if to prove that when there's no time for procrastination and worry I can just get on with stuff, I manage to book my travel and hotel, sort childcare and a dog-sitter, and pack a bag—in lightning-quick time. I arrive late in the evening and quickly decide against wandering the streets to find something interesting to write about my visit so far. What if I’ve accidentally booked into a hotel in the dodgy quarter? It was quite cheap…. So, with my threat-detection system very much in charge, I turn my back on the prospect of a cold Belgian beer and head upstairs to bed.

The next morning, Jonas Everaert, one of Koster's PhD students, meets me at the hotel and walks me through the backstreets of Ghent (the not-so-pretty end—maybe I made the right decision last night) to the university. He gallantly balances my bag on the back of his bike, and we chat about all kinds of brain-changing technologies, including meditation. He tells me that brain-imaging studies with Buddhist monks have shown that their amygdala reactivity has dropped so low through constant meditation that it is no longer workable in modern life—they simply couldn’t deal with the levels of stress and threat that the rest of us do. I don’t want to take it that far, clearly, but a little more Zen might be nice. Still, it's interesting to get another insight into the pros and cons of meditation. The way most people are talking about meditation these days, you’d think it was the cure for everything.

Jonas takes me to Ernst's office—which looks pretty much like every scientist's office I have been to: a plain white room with piles of papers from floor to ceiling and all over the desk. While Jonas goes off to get us a coffee, Ernst welcomes me in and apologizes in advance for the terrible coffee I am about to drink. He listens, seeming both interested and a little amused, to my bumbling explanation of what I’m trying to do to my brain. I can’t help wondering if these researchers think I’m on some kind of fool's errand and are politely humoring me because it makes a change from writing grant proposals. Does he really believe that he can turn my worry-prone mind into a chilled-out positive one in just a few weeks? I guess we’ll see.

A few minutes later, there is a knock at the door and in come two of his research team. Ayse Berna Sari is shy and friendly, with the doe eyes of Audrey Hepburn and the big hair of Amy Winehouse. She and Alvaro Sanchez Lopez (who is a lot closer to the common stereotype of a scientist) point out to us both that it's going to be difficult for me to try their attentional-bias training program because it involves disentangling emotion-laden sentences—and they are all in Dutch (the main language spoken in this part of Belgium). Instead, they say, they can give me the working-memory training program that Berna has been working on and see if it improves my performance on Alvaro's tests. In a recent study, they have found it to be useful in changing people's cognitive biases after just a couple of weeks of training five days per week. Despite everything I have already heard about working-memory training, and the controversy over whether it works, it all sounds very intriguing.

First come the now-familiar baseline tests, for which they take me to a white breeze-block-walled room with tiny windows too high to see out of. What is it with psychologists and their stark, windowless rooms? It's no wonder they do so well at finding anxiety in more or less normal people.

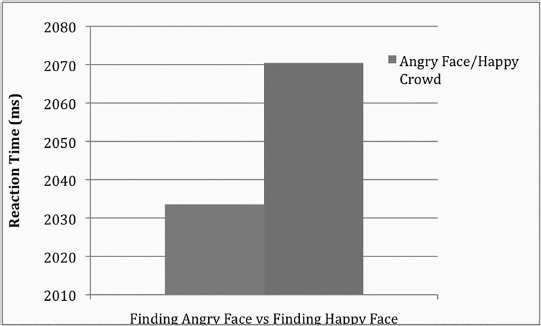

The first test was a more sophisticated version of the cognitive-bias test I did earlier, online. On the computer screen in front of me, a circle of black-and-white faces pop up briefly on the screen. Berna tells me they will either look angry, happy, or neutral. If all faces match, I am to do nothing. If one is different from the others, I press the spacebar.

It's actually surprisingly uncomfortable to have so many faces staring at you at once. The angry ones feel threatening, but, if anything, the neutral ones are worse—their blank stares make me wonder what they are thinking. I find this in real life, too. I’d rather someone was looking at me as if I was a piece of scum than just staring blankly. At least I’d know what I was dealing with. The smiling ones are kind of comforting, though—they give me the warm, fuzzy feeling of being in a roomful of friends who like me the way I am. Consciously, I’d much rather look at the happy folk, but, like the online version I’d done, Berna's results show that it actually takes me longer—about forty milliseconds longer—to drag my eyes away from angry faces and spot a happy one than it does to find a single angry person in a sea of smilers (see figure 2.4).

It doesn’t sound like a lot, thirty-one to forty milliseconds, but compared to participants in their previous experiments, it is quite high, Ernst tells me later. In a 2006 study, high trait-anxious people had a negative bias of ten to thirty milliseconds, compared to less than ten milliseconds in low-anxious folk.13 Again, I find myself lingering near the end of the scale based on volunteers from previous studies. Oh dear.

Figure 2.4. It took me forty milliseconds longer to look away from angry faces than happy ones, despite the angry ones making me feel uncomfortable.

After a few more baseline measurements—including one particularly horrible test where I have to look at photographs of sick babies and lonely old people, and then try to come up with a positive spin on the situation before rating how upset I feel—I go for a walk to rest my eyes. On the way back, I spot Alvaro in a room, setting up his eye-tracking experiments for me to try later. I persuade him to let me have a go at the eye-tracker now, and it's all good fun until Berna appears and gently points out that I’m in the middle of assessment and supposed to be taking a break. Fair point, but I make sure to get straight back to the eye-tracking room as soon as Berna has finished with me.

The last time I tried an eye-tracker in a psychology lab, about ten years ago, it looked like something out of Stanley Kubrick's Clockwork Orange—a pair of enormous glasses attached to a headset with cameras that stare into your eyes. But not anymore. Now, the equipment looks like a shiny pair of speakers attached to the bottom of a computer screen. Apparently, the shiny bit beams infrared light into the eyes, and a hidden camera in the screen is picking up the reflections from the pupils. Human eyes can’t see infrared, so the only clue that the machine is following my eye movements is when Alvaro begins calibrating the machine and two white dots appear on the screen: the computer’s-eye view of my pupils.

It looks as if an inquisitive little robot is looking back at me from the screen. When I blink, it blinks. When I tilt my head, it tilts its head, too. It's like having a virtual pet—I’m sure there's an app in this somewhere. It soon has all three of us in fits of giggles, until Alvaro snaps back into researcher mode and instructs me to stay still so he can finish the calibration. I do as I’m told and track a red dot around the screen while the eye-tracker follows my eyes.

First, Alvaro shows me their Dutch-language training test. Six words come up on the screen; I’m told each series of words makes up a jumbled-up emotional sentence, but only using five of the words. For example, “I a person am useless worthwhile.” Depending on the direction of their bias, people tend to either make positive sentences (“I am a worthwhile person”) or negative ones (“I am a useless person”). The eye-tracker can spot where your eyes first go to—so even if someone comes up with a positive sentence in the end, the computer knows you looked at the negative option first. Clever. As a training device, as the eye-tracker measures where your eyes flick to first, the words change color: green for positive words and red for negative ones. Your aim is to go straight to the positive ones and avoid the red. I only know two phrases in Dutch, and both of them involve swearing, so clearly I have no chance of doing this test properly. After a couple of examples flash up on the screen, though, we both start to laugh. Even in a foreign language, my eyes seem drawn like a magnet to the negative words. Figures.

Next, Alvaro sends me back to the other room for a bout of working-memory training with Berna. I am to do two twenty-minute sessions and then do the horrible photos tests again—my least favorite so far—to see if anything has changed. I am skeptical that anything will change after just forty minutes of training, but Berna tells me that they have seen a shift in experiments on larger numbers of people, so it isn’t impossible. And, she says, the people with the most negative cognitive bias were the ones whose score improved the most after training.

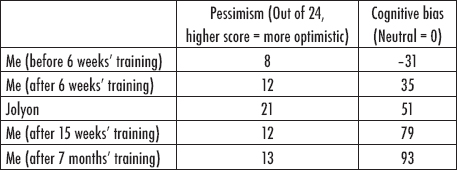

Figure 2.5. Dual N-back working-memory training. You can download the game at http://brainworkshop.sourceforge.net. (Courtesy of Paul Hoskinson and Jonathan Toomim)

So, after two more really difficult twenty-minute working-memory sessions, I again find myself looking at miserable photos. Depending on whether the word “appraise” or “reappraise” pops up on the screen afterward, I am to spend the next thirty seconds dwelling on either the most miserable explanation or how there was a positive outcome in the end. When the picture showed a baby in an incubator, for example, I could either focus on the suffering of the baby and its parents, and the odds of it not surviving, or imagine that baby growing up big and strong and leading a happy and fulfilling life. Before and after each of my little reveries about the picture, I had to rate how I felt on a scale of 0 (all right, actually) to 9 (utterly miserable). I find this test pretty difficult; you only get a few seconds to think about each picture, which doesn’t feel long enough to generate any real emotion—and the scoring seems rather fixed: who wouldn’t rate their mood as improving after putting a positive spin on a sad picture? It all feels a bit forced. Still, I am intrigued to see if my scores have changed from before the working-memory training.

And according to this very quick bout of working-memory training, it did change my ability to compute different options (see figure 2.6). I even scored better than the average volunteer, for once.

The idea behind improving working memory is that it buys room in the mind to weigh up different interpretations of a situation—to do the math of is it really all that bad or is it possible that I am overreacting?

I can’t say I’m convinced that my results above reflect any real change in my thought processes in general, but at least if you take the scores with a huge pinch of salt (comparing one person against the average isn’t what happens in science studies; they work by calculating averages from large numbers of people), it does look as if it may have briefly improved my ability to think a bit more positively. Would I do the training every day, though? It's quite boring…. Well, I’m about to find out because I have promised to do their working-memory training for three weeks. Partly to see if it does anything for my anxious streak, and partly to test the brain-training spiel about an improved working memory making you smarter in general.

A few days after I get home from Ghent, though, I take a hiatus in my training when Elaine emails asking if I would like to take part in a training study in her lab in Oxford. Elaine's is a real study that will be published in a scientific journal at some point, and I don’t want to mess up her results by doing two lots of training. So I put the Ghent experiment on the back burner while I go to Oxford.

Figure 2.6. I started off with a below-average ability to think positively about ambiguous photos but then, after forty minutes of working-memory training, shot ahead. The average is taken from the group's previous research.

The day before I am due at Elaine's lab, I get an email from Alex Temple-McCune telling me where to be and when. The email ends with a polite request to please arrive there on time. By now, I’ve had quite a lot of experience with cognitive psychologists, and I can’t help wondering if this is some kind of trick to get me worrying for the purposes of the experiment.

They needn’t have bothered. My traveling to Oxford coincides with a train strike, and the train I had been planning to get had been canceled. The evening before I’m due in Oxford for the experiment, my anxiety levels go through the roof as I hastily make arrangements to drop my son off with a friend before school, so that I can get an earlier train. That night, I dream about empty train stations, being unable to find my car to drive to the station, and generally running around trying to get there on time.

It all works out fine, and (despite the taxi driver triumphantly announcing “here we are” on Keble Street, when I’d asked for South Parks Road, leaving me a good ten-minute walk from the lab) I get there bang on time and am met at the door by a smiling Alex.

First, I have to fill in multiple questionnaires about my state of mind today (state) and in general (trait). I have done a lot of these now, and they don’t get any more stimulating. Then I go on to do what I think is a working-memory test, involving colored shapes in various positions on the screen, which I am supposed to remember having seen them for a fraction of a second. I do several sessions back to back (there are opportunities for short breaks, but I’m not really sure where to look or what else to do—I’m in a white concrete box, and it doesn’t feel like the time for making polite chitchat).

Then Alex asks me to swap chairs so that we can do what sounds a lot like mindfulness meditation. My job is to focus on my breathing for five minutes and if my mind wanders try to bring it back to focusing on breathing. Randomly, the computer will beep and I have to tell Alex whether I am focused on breathing or on another thought. If it's another thought, I have to tell him if it is positive, negative, or neutral, along with a few words describing the thought. It's incredibly embarrassing. Examples of my thoughts include the following: This room is really cold-looking; I hope I don’t fall asleep; I think I’ve got a headache coming; I hope I’m not ruining their experiment; This is taking ages. All of them are negative. Some I don’t even admit to. The thought, “Has he noticed I missed my knees when I shaved my legs?” I kept to myself.

Then comes the “five-minute worry.” This is as awful as I expected. I can see the car hitting my boy outside of my house and what it does to his head. I can see him lying there covered in blood and me screaming. I can imagine him being in the hospital in a coma, and the possible horrible outcomes—death, paralysis, brain damage. By the time Alex comes back in, I am in a right state, feeling exhausted, tense, and downright miserable.

And now we are going to do the breathing exercise again. This time my thoughts start off even more negative: I want to go to sleep; I can see the horrible things I imagined in the five minutes; I’ve had enough of this. Gradually, I go back to some kind of baseline, my last thought being, I feel more relaxed now than I did at the start.

At the end of all this, I feel like a wrung-out rag and I’m happy when they demonstrate the training I’m to do and then let me go. The training will take about an hour a day, every day—even weekends—and I’m going to do it for ten days. The lab can track my progress online, so they will know if I’ve been skiving. Yep, okay, anything you say, just get me out of here. Alex walks me around for a quick chat with Elaine and, still looking a bit concerned about my state of mind, says good-bye.

POSITIVE-THINKING BRAINWASH GUINEA PIG: THE OXFORD STUDY

When I get home and start my training, it quickly becomes clear that I have been assigned to the control condition for the working-memory part of the study. This I’m not happy about, but unfortunately this is the way randomized trials work: each subject is randomly assigned to a group whether the subject is a student volunteer or a nosy journalist wanting to have a go. I’m not supposed to know it's the control condition, but I happen to know from my time in Ghent that this kind of training should get harder as you improve—and it has been on the easiest level for ages, despite my near-perfect scores.

I’m pretty sure I’m in the active (training) condition for the interpretive bias part of the study, though. The training is basically twenty minutes of audio of a lady with a lovely, gentle Dutch accent reading little stories about situations that you could view either negatively or positively. The situations all take the form of the following: “So this happened, you freaked out about it, then decided it was probably fine. Is it fine?” The correct answer, clearly, is, “Yes.” I get a green frame and a ding! for a correct answer and a red frame and a buzz for a wrong answer. It starts to feel slightly hypnotic, as if I’m being brainwashed into seeing the brighter side of situations.

Stranger still, when a stressful situation happens in real life, I find I’m talking myself down in a calm Dutch accent. Okay, so there are only ten minutes before I have to take my son to school, and I still haven’t made it into the shower. But my son is fed and in his uniform, his bag is packed and by the door, and I have cleared the kitchen after breakfast. I have just enough time to shower, dress, brush my teeth, and go. Normally, I’d spend this last ten minutes of the morning running around, shouting at everyone, and tripping over the dog. But today…“Is it going to be fine? Yeeeessss.”

It doesn’t take long for the Zen to wear off, though. When the study is over, I try to invoke the calming voice of the Dutch lady whenever I worry, but, increasingly, it feels forced. Worse, Alex won’t tell me whether my two weeks of brainwashing made me any better at staying calm during the five-minute worry, because they will be analyzing everyone's results together when they have collected all the data—another annoying feature of being in a real study, it turns out. But while it seems my ability to think positive probably did shift a bit, the effect barely lasted a week; so, even if it did give them an interesting result for their experiment, I don’t think it is the cure I was hoping for. And if it takes twenty minutes of boring brainwashing every day to achieve, I don’t think it would be a viable long-term strategy anyway.

So it's back to the working-memory training from Ghent, with a side order of online click the smiley face—a bit of cognitive bias and a bit of increasing the mental workspace. I do the exercises religiously, every day for six weeks—even on holiday—and then take the cognitive bias and optimism tests again.

And…something changes.

Figure 2.7. Before training, I had a resolutely negative bias compared to my optimistic friend Jolyon. After training, my cognitive bias shifted toward, and eventually past, his. My optimism score, however, remained stable.

I email Elaine the results. After pointing out that it's difficult to make real assessments from a sample of one, she did say this: “Clearly your bias has shifted from negative to positive. This indicates that your attention is automatically now shifting towards the positive images, whereas previous it was automatically pulled by the negative—more similar to your optimistic friend. So all good and as expected.”

I keep the training up over the following weeks and months, and it goes even further—way past the giddy heights of Jolyon and heading toward 100 percent. Interestingly, though, my natural pessimism score stays stubbornly where it began. I might worry less, but I don’t expect everything to go my way.

Another measure of change is to redo the standardized anxiety scale (STAI-T) that I did at the start of this process, in Ernst Koster's lab in Ghent. And again, it seems as if something has shifted. Before, my score on the trait-anxiety scale was 60/80. After, it was 49. “There is a decrease, indeed,” wrote Koster, to my mind sounding a little unimpressed. Actually, it might be quite significant. According to research on large groups of people, a score of less than 48 indicates no anxiety at all, whereas 60 is pretty high—the kind of score you’d expect from someone with an anxiety disorder. Which is good news and bad, as far as I’m concerned. I started this process thinking I was just your average worrier. It looks as if I started off with a big problem—but on the plus side, I have turned it around, and my score looks vaguely normal.14 It's a success of sorts….

It's nice to know the numbers are moving in the right direction, but it's more difficult to tell whether it has changed anything about the way I think in real life. And that's really the nub of it—it's no use changing your cognitive bias or STAI-T score if it doesn’t make you feel any different. I can’t ask anyone else if I seem more chilled—even my husband—because a lot of my worrying is a private affair in my own head (for what it's worth, I did ask him and he hasn’t noticed any changes). Ultimately, a subjective take on whether life feels any easier is the real proof of the pudding.

The problem with this is that cognitive biases are under the radar of consciousness, and by definition you can’t be aware of the unconscious. Which means that if I have changed, then I probably won’t notice and if I think I do, I’m probably imagining it. Having said that, though, I do feel like I am slightly less self-conscious in situations where I have to chat to people I don’t know very well. It feels like I might be getting better at spotting a friendly face and letting go of signs that may be interpreted as disapproval. This in turn doesn’t give me any room to ponder whether that face is saying, “God, she's awful,” or whether it bears no reflection on me at all.

Spending all that time looking at smiling and angry faces has also given me a handy demonstration of how a smile (or a grumpy face) can make other people feel. I find myself smiling at people more and saying, “How are you?” and that in turn makes them smile more at me—which is nice. This makes me think that it is probably worth keeping on with the happy-face clicking, to see if anything changes longer term. Nowadays, it only takes about five minutes, and I often do it while the kettle is boiling.

On the downside, since taking on the training, I have noticed an upsurge of anxiety-ridden dreams—ones where I have an exam and have forgotten to study, where my teeth are crumbling in my head, or where my trousers are pulled down in public and everyone points and laughs at me. It makes me wonder if this is where my worries have gone to hide now that they aren’t welcome in my conscious mind. Like that bit in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind where you find out that the memories are hiding so they won’t be deleted, my mind isn’t willing to give up its old ways just yet.

One thing I do know is that, looking back on the diary I’ve been keeping throughout the process, I don’t feel like this anymore:

Day 1 and 2 (July 2015)

I’m finding the training quite unsettling, and it feels like it might actually be doing me harm. I’m looking at far more negative faces than positive ones, and it's making me feel really uncomfortable. It takes ages to find the smiling ones, and all the time I’m looking at the angry ones I’m getting more and more uptight. I get a wave of relief every time I find a smiling face. It's like a port in a storm.

Now it's more like what I noted on my diary on day 63 (September 2015):

I don’t feel like I did in the first week, where the angry faces were really upsetting. Now, it's just a quick “bam, bam, bam” and it's done in five minutes. Really think I could keep this up long term….

As for the working-memory training, I’m less convinced. It proved difficult to stay motivated when my performance plateaued after several weeks. I carried on doing it for a while, but not for twenty minutes and not every day. A couple of months later, I stopped altogether. There just isn’t enough evidence to convince me that it's worth my time yet.

The road outside my house still gives me the jitters, but I have found a way around it: we now go a longer but quieter way to school, riding our bikes along a wide pavement instead of walking up a very narrow one. I don’t know why I didn’t think of it before—maybe practicing how to replace panic with a calm focus has helped make room in my brain to not just fret about the road but to think of a solution as well.

One thing has proven particularly resistant to change: my ridiculous response to stress. About halfway through the Oxford study, while trying to set up the brain scans for the next stage of my mission, I had several knock-backs from researchers who I had hoped would let me have a go on some of their experiments. It was, various researchers told me, too expensive, and they couldn’t spare the time to find a student to analyze my results, and that, anyway, I don’t qualify as a subject for any study they were running. And even though I know that brain scans only tell you so much and that there are other, perhaps more reliable ways of measuring brain change, I did freak out on a similar scale to the Elaine Fox debacle when I was waiting to hear back from her (admittedly only for a few days this time, but I wasn’t much good for anything for a while). I can’t deny it was disappointing. I had hoped to knock this kind of thing on the head.

This goes back to the idea that to stand any chance of changing your brain, you have to pick your skills very carefully. An anxious temperament, I have found, isn’t born of one thing but many. Social anxiety and performance anxiety are completely different things, and what helps with one may not help the other.

What I take from all of this is that getting on top of anxiety is, again, all about controlling attention. Unfortunately our attention is not always under our conscious control—and that's why self-help alone, at least in the form of advice such as “think yourself better and you will get better” is never going to work. If you have a negative bias, you will always be swimming against the tide. It's why depressed people can’t think themselves out of the hole: their brain is feeding them nothing but the hole.

Escaping the clutches of a negative bias is definitely not easy. I can’t say for sure if cognitive-bias modification is the answer, and neither can Elaine Fox or anyone else. All I can say is that, for me, it seemed to help. But—and it's a big “but”—“pick your skills” definitely applies here. Train yourself to seek out happy faces, and that is what will change in the real world. I wondered at the start of all this whether fixing one neurosis would make all the others melt away too. The answer to that is a definite no.

On the other hand, my mindfulness course is now well underway, and in theory I have a few more tools to counter a more general kind of angst. Mindfulness, I am discovering, is not just about the mind, but it's about the body too. And that might be the key to greater control.

THE MEDITATION DIARIES: PART 2

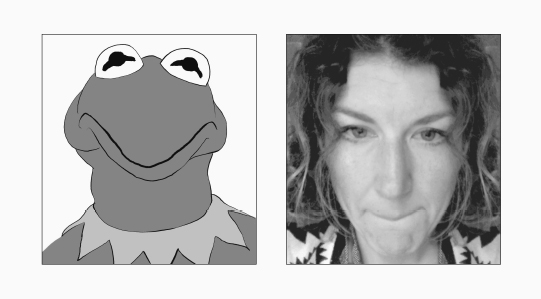

In Fifty Shades of Grey, Anastasia has a habit of biting her bottom lip whenever she's nervous. She doesn’t realize she's doing it, but it drives the sexy billionaire Christian Grey mad with lust. Through the powers of meditation, I have discovered that I do something similar. Only I look more like Kermit the Frog:

Figure 2.8. My worry face—or is it Kermit the Frog?

Weirdly, I had never noticed this habit until Gill, my mindfulness teacher, gave us the session on noticing what is happening in the body; our homework was to pick a pleasant experience and pay attention to where we feel it in the body—and then do the same with an unpleasant experience. I noticed that, when I’m having a warm and fuzzy moment with my loved ones, I feel it as a warm spreading sensation in my belly—which is all very lovely but not terribly surprising. More interestingly, when it comes to the negative stuff, I noticed that I have all manner of physical stress tics that come out whenever I get uptight. Kermit-face is the most common, but I also have a particularly unattractive frown and a pursed-lip look like a disapproving granny.

The value of noticing this, from my understanding of what Gill says, is that it opens up a gap between what the mind is doing and how it feels. Only then can we investigate what is going on. “It's about noticing,” she says. “Just noticing.”

The more I pay attention to these physical tics, the more I realize there is an underlying theme. I bite my lip when I am cleaning up the house, when I am thinking about what to write, when I am cooking, and when I am writing my to-do list. The underlying theme is, I want to do this right. What if I screw it up? Am I crap at this? Interesting.

Even better, now that I have noticed that I do this, I can consciously let go of my lip and point my attention directly at whatever it is I am so worried about. Then I can realize that either a) there's no need to get all Kermit-faced about loading the dishwasher, or b) I’m stressed because I care about the quality of my work—and that's a good thing. Either way, it helps to take the pressure off and give myself a bit of a break. It's actually pretty fantastic.

Another thing that I am starting to like about mindfulness is that it doesn’t allow any room for giving yourself a hard time about doing things “right.” Every bit of self-help that I have ever seen involves an element of “You feel this way because you are doing it wrong. Do it this way and you will feel better.” Mindfulness allows you to notice your unhelpful habits without adding yet another nagging voice to the mix. Instead of “I’m stressing; why am I stressing? I shouldn’t be stressing, et cetera, et cetera,” with mindfulness it's more like, “I’m stressing. I have noticed. That is all.”

I think I am starting to see a real benefit to this approach—it might be a way to reach the neuroses buried in my mind that cognitive-bias modification couldn’t.

INTERVIEWS/CONVERSATIONS:

Alexander Temple-McCune, conversations during lab visit and experiments at Oxford University, July 10, 2015.

Jolyon, conversations during visit, July 9–11, 2015.

Elaine Fox, in an interview during lab visit and experiments at Oxford University, July 10, 2015.

Geraint Rees, in an email interview, February 10, 2015.

Ernst Koster, Skype call, June 12, 2015.

Ayse Berna Sari and Alvaro Sanchez Lopez, conversations and interview during lab visit June 18, 2015.

Ersnt Koster, follow-up email interview, September 16, 2015.

Gill Johnson, as part of meditation course, September 24–November 12, 2015.