In the beginning, everything was fawdah [chaos].

—I-8L

CHAOS AFTER THE NAKBAH

The most common word that Palestinians used to describe early life in the refugee camps was fawdah, meaning chaos or anarchy. After the disaster of the 1948 war, Palestinians were thrust into unfamiliar surroundings in host countries strewn across the Middle East. Besides meeting the most basic human needs, aid organizations or host states provided little support in governing the camps. A purposeful “protection gap” meant that Palestinians had to transition from rural Palestinian villages to refugee camp life on their own. A cinderblock and tile manufacturer described the early transition: “We started from scratch in the camps. There was nothing. We pulled ourselves out of the dirt” (I-28L).

In the midst of the chaos, Palestinians created order through informal property rights. These rules protected their belongings and preserved their community. I begin by tracing how Palestinians were treated upon their arrival in host countries and how UNRWA brokered camp agreements with Jordan and Lebanon. To create a holistic picture of the early years, I use historical accounts, scholarly articles, UNRWA information sheets, and interview data. The early years of chaos that resulted from the protection gap created similar pathways to informal property rights formation in Jordan and Lebanon. As a result, I pool interview data on the initial years following the

Nakbah in camps across Jordan and Lebanon.

Initially, Palestinian villages tried to resolve the chaos through violent clashes. However, early camp battles were not productive and led to increasing disharmony because no single Palestinian village could claim victory and dominate the camps. At the same time, entrepreneurial Palestinians were slowly growing small businesses. In this climate, Palestinians felt they had no other choice than to adopt a system of property rights that established order. In interviews, Palestinians said they overcame disunity and borrowed from pre-1948 village templates of property ownership experienced under Ottoman and British rule to meet challenges in the camps.

Though Palestinians had myriad traditions from which to borrow and inform their system of rules in camps across Jordan and Lebanon, they strategically chose experiences that emphasized the ahl (family) or hamula (tribe) as the primary organizing unit in the camps and village norms of honor and ‘ayb (shame) to enforce informal property claims when there was no state to govern. Across camps, informal property rights evolved organically and in a manner similar to some of the expectations of the spontaneous order theory of institutional formation. Informal property rights were far from perfect, with unresolved property disputes turning into revenge schemes sometimes spiraling into violence among families. Still, informal property rights did offer a measure of asset protection and buffered the community from co-optation by powerful outsiders in a transitional space.

Jordan’s initial response to the influx of Palestinian refugees reflected local conditions in the nascent Hashemite monarchy. Jordan was an artificial imperial creation carved out by British and Western powers. Jordan’s leaders sought to tame and control disparate Bedouin and regional factions. King Abdallah I worked tirelessly to co-opt factions and consolidate his regime. Historians describe the difficult challenges that Jordan’s kings faced because of their historical roots. For example, “King Hussein was fundamentally and structurally a client king…for all practical purposes the Hashemite legacy inherited from his grandfather was one of continuing dependence on the West” (Shlaim 2008, 154). Jordan was a poor country between 1949 and 1967. It had been desperately poor as the Amirate of Transjordan and the addition of Palestinians, half of who were refugees, aggravated the economic situation (Dann 1989, 11). British and American subsidies were essential components of the funding of the Hashemite state. Funds from UNRWA also helped balance the early state budget. In many ways, Jordan depended upon “Western handouts” for economic survival (Dann 1989, 11).

The drastic influx of Palestinian refugees in 1948 represented a pivotal strategic issue for Jordanian leadership. On one hand, Palestinians represented a potential source of destabilization. At the time, Jordan’s estimated population ranged from 340,000 to 400,000 people. Following the Nakbah of 1948, the Jordanian-Palestinian Committee for the Study of Living Conditions of Refugees estimated that 506,200 or 55 percent of all Palestinian refugees fled to Jordan. Palestinian refugees caused the population of Jordan to triple within two short years. Even today, Jordan houses the largest number of Palestinian refugees in the Middle East. Coupled with the assassination of King Abdullah I in 1951 and the tumultuous transition to power among family members when King Hussein assumed the throne in 1953, Jordan’s leadership was facing an uncertain political landscape.

On the other hand, consolidating power over the Palestinians could signal the strength and power of Jordan in domestic, regional, and international political arenas. Jordan offered Palestinians citizenship. However, their transitional community status remained despite these advances. Palestinians still faced limits on their employment activities and citizenship conferred very different meanings depending upon their year of arrival, place of origin, and political connections in Jordan. Edward Said describes a visit to Jordan in 1967 and explains the feeling most Palestinians had about Jordan at the time. He writes, “Yet, so far as I could tell—and this was certainly true for me—no one really felt at home in Amman, and yet no Palestinian could feel more at home anywhere else now” (Said 1994, 6).

To deal with the Palestinians, the Jordanian government developed a specific branch, linked to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, to be in charge of dealing with Palestinian refugees (

www.dpa.gov.jo/). This branch, known today as the Department of Palestinian Affairs (DPA), has had a variety of names over the decades but has fulfilled the same functions. Initially, the DPA was known as the Ministry of Refugees and partnered with UNRWA. It dealt with issues like the establishment of suitable plots of land for the camps, the issuance of legal identification documents, and the provision of basic humanitarian needs. From 1951 to 1967, the DPA was called the Ministry of Construction and Restoration, and the organization at the time focused on the improvement of physical conditions in the camps (

www.dpa.gov.jo/). From 1967 to 1971 the DPA was known as the High Ministerial Council (

www.dpa.gov.jo/).

For Palestinians, early life in Jordan was difficult and reflective of a transitional political landscape:

Most of us arrived with nothing. We had no way to earn a living. Almost all of us were farmers that now lived in a cramped urban spot. Everyday, just to get enough food and water was difficult. And people think of Jordan as a warm desert. Hah! But at night and during the winter months it was freezing cold and snowed. We focused on creating a better home to stay warm. (I-2J)

“The basic struggle was simply to survive, political organizing or activity was a luxury few could afford” (Gubser 1983, 15). Palestinian refugees in Jordan worked to cobble together an existence. After visiting camps in Jordan in 1964, the UNRWA commissioner-general reported that “a large part of the refugee community is still living today in dire poverty, often under pathetic and in some cases appalling conditions” (Brand 1988, 153).

In sum, the early decades in Palestinian refugee camps were very difficult for the community to thrive. Though Jordan developed a system to deal with the basic needs of Palestinians, the refugee camps still represented a transitional space with serious protection gaps that had little support on issues of governance.

PALESTINIANS IN LEBANON

In Lebanon, conditions were extremely challenging for Palestinians. Lebanon was ill-prepared to handle the initial influx of Palestinians in 1948 when the Nakbah or the catastrophic 1948 war created the refugee situation (Schiff 1993). Many have characterized the Lebanese state as a “reluctant host” to Palestinian refugees since 1948 (Knudsen 2009). In this capacity, the Lebanese state sought to prevent the permanent integration and settlement of Palestinians in the country. The state structure strategically isolated the Palestinian community, creating a transitional political economic space. They created purposeful protection gaps that denied Palestinians many basic rights and placed them in “legal limbo” (Knudsen 2009). One refugee camp leader described the camps as “isolated islands” swimming in a Lebanese ocean (I-26L).

The early years were impossibly hard. A Palestinian refugee that walked to Lebanon in 1948 and grew up in the camps recalled what life was like for his family:

My mother contracted an easily preventable disease, tetanus, and died in the camp of a horrible death. My father was broken after he lost everything in Palestine because he had no future as a farmer in the refugee camp. I remember feeling hungry all the time. There were seven kids in our family to feed. Once, I recall my family had run out of pita bread. There was not a morsel of food in the house. Not having even a single piece of bread was a desperate sign. I was so worried and starving. God must have been watching out for us on that day, because I was walking and praying and, suddenly, I found a Lebanese coin on the ground. I took it to the falafel shop and bought fresh hot falafel, hummus, and bread for my family. We all got to eat! It was a rare feast. Somehow we survived those times. (I-96L)

Lebanon was neither socially nor politically welcoming of Palestinian refugees. Host country policy laid the foundation for a transitional Palestinian space. Lebanese citizens believed the presence of Palestinians upset the delicate balance among religious sects in their confessional political system. In this type of political system, each religious group is designated a number of parliamentary seats based on their demographic representation. The influx of Sunni Palestinians would disrupt a fragile political compromise.

In particular, the Palestinian situation in Lebanon was marked by a refusal of

tawtin, or resettlement.

1 In national surveys, an overwhelming percentage of the Lebanese population, regardless of sectarian affiliation, refused

tawtin for Palestinians. In one survey, 87 percent of Maronites, 78 percent of Shiites, 78 percent of Catholics, 78 percent of orthodox, 71 percent of Druze, and 63 percent of Sunnis in Lebanon opposed

tawtin (Sayigh 1995). These surveys indicate that Lebanese citizens disagreed with Palestinian resettlement or integration into broader Lebanese society.

Aside from informal social isolation, Lebanon codified their desire for the legal isolation of Palestinian refugees through work restrictions and impositions against property ownership outside the refugee camps. Palestinians in Lebanon, unlike those living Jordan, were not issued passports. They could sometimes attain laissez-passer travel documents, but these were difficult to access in many circumstances. In addition to limitations on travel within and outside the country, Lebanon’s 1964 and 1995 laws outlined the rights and responsibilities of foreigners to live and work in Lebanon, identifying Palestinians as a special case independent of the treatment of most foreign nationals. For example, in Lebanon, Palestinians are banned from seventy professions. One commentator wondered, “Can you imagine a Palestinian refugee family who has lived in Lebanon for over 50 years without the right to work?” (Christoff 2004). In addition, a 2002 law forbade Palestinians from owning land or buying property in Lebanon (Christoff 2004). In effect, Palestinian refugee camps occupied a transitional space that legally isolated them from formal state structures in Lebanon.

UNRWA BROKERED REFUGEE CAMPS

Host countries and international aid organizations scrambled to accommodate Palestinian refugees after 1948. The Red Cross was the first to administer aid to Palestinians (I-91L). Once UNRWA was established, it took over the task of providing assistance to Palestinian refugees. Though UNRWA was mandated with this power, Palestinians were weary of UNRWA’s motives and activities. After all, many Palestinians felt that it was the UN partition of Palestine that was partially responsible for their displacement in the first place (I-91L). In this precarious context, UNRWA acted as the primary broker and welfare advocate for the Palestinian people in Lebanon and Jordan. “UNRWA brokered humanitarian agreements with host country governments to allocate land for Palestinian refugee use” (I-3J, I-21L). This agreement was revised in 1967 to accommodate the influx of Palestinians who fled Gaza following the Arab defeat in the 1967 Arab-Israeli War (I-3J, I-2L).

UNRWA’s public information officer in Jordan noted, “The land was given from the Hashemite Kingdom to UNRWA. It is not clear how Jordan procured the land for Palestinian use but when UNRWA was given it, it was responsible for providing it, and other services like health, welfare, and education to Palestinian refugees” (I-3J). Additionally, UNRWA’s public information officer in Lebanon stated, “UNRWA contracted with the Lebanese to find suitable land for Palestinians. Host countries played no role in how the land was divided up for Palestinian use” (I-21J).

Lebanon agreed to lease land to UNRWA for Palestinian use for ninety-nine years, but the host country absolved itself of any role in the division and use of land among refugees (I-3J, I-21L). Some land allocated for Palestinian use was also on indefinite loan from religious institutions and private families (Roberts 2010, 77). In over one hundred interviews in Lebanon, there was never a clear understanding of who originally owned the land that camps occupy or what the ninety-nine-year lease agreement meant for the host country and the refugee population in the long term. Other experts of Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon and Jordan agree that the policy is ambiguous and complex. Though some characterize the ambiguity of the land agreement as a disadvantage for Palestinians, the political ambiguity of this space also provides for opportunity (Roberts 2010). The ambiguity advantaged Palestinians because it gave them the freedom to develop institutions of protection that reflected their community needs.

Refugee camps in Jordan and Lebanon were set up on small areas of uncultivated land or on abandoned military campsites formerly occupied by colonial armies. Conditions were “primitive in the extreme” up until the early 1950s (Sirhan 1975). Over time, sand and earth were covered by cement and tents gave way to shacks that were eventually replaced by cement block homes. Gradually, latrines were replaced by private installations. Originally, UNRWA supplied water through tankers. Only 35 percent of homes in the camps had electricity and only 40 percent of homes had running water by the late 1960s (Sirhan 1975). Camps have roughly remained the same size since their inception, but population growth has continued unabated. As a result, there is a high population density in the camps.

At first, UNRWA adopted the role of allocating resources, like land, to Palestinian refugees. UNRWA allotted each family a plot of land and a tent based on the number of family members in each grouping (I-2J, I-3J, I-2L, I-3L, I-21L, I-29L). For example, every six to eight family members received a tent and small plot of land (I-2J, I-3J, I-2L, I-3L, I-21L, I-29L). An UNRWA officer explained the early arrangements with Palestinian refugees:

Families received one tent apiece. Huge families of more than eight members were given second tents. They were assigned a plot of land and the spot was registered with their corresponding family registration number. After three or four years people fenced in the plots. By the mid-1950s, the agency [UNRWA] replaced tents with shelters or huts. The rooms were covered with sheeting materials for roofing. (I-3J)

Refugee camps looked like large tented fields that were filled with thousands of Palestinians living impossibly close to one another. Single-family tents were called “bell tents” because they were shaped like a bell (I-91L). Larger families often lived in “Indian” tents that looked like Native American teepees (I-91L). In addition, medical and school tents resembled the shapes of “circus” tents and were set up to provide basic services to residents (I-91L). A Palestinian man that grew up in Nahr al-Bared in the early 1950s fondly recalled windy days in the camps. “When I was a child I thought windy days were the best. A big gust would pick up and topple our school tent! The teacher would be so mad and sand would be kicked up everywhere. He would dismiss us early because there was nowhere for him to teach until the tent was put up again. I could go and play instead of study” (I-96L).

UNRWA held a lot of authority in the initial distribution of resources inside the camps, but the organization held an explicit policy of not interfering with the informal transfer of resources among refugees (I-3J). One UNRWA representative commented that “we didn’t play politics inside the camps, we just helped to provide Palestinians with services. What they decided to do with them [land, food, water] was up to them” (I-5L). Another said, “Palestinians were given the right to use the land inside the refugee camps and develop it in the way they saw fit without UNRWA, host country, or local political interference” (I-21L). In Jordan, a public information officer said, “UNRWA is not a government and the refugees are not our subjects” (I-3J).

Palestinians were left to create order and find protection in the camps because host countries and UNRWA absolved themselves of any role in governing the camps. Though no one expected the refugee crisis to continue for as long as it has, the protection gap ultimately gave Palestinians a new lease on life. Palestinians could seize the opportunity to develop the dirt they now occupied. Palestinian communities could build homes, establish businesses, create plumbing and sewage systems, and establish electrical systems in what was otherwise a barren landscape inside the camps. Of course, none of these innovations happened immediately.

COMMUNAL TENSION AFTER NAKBAH

Initially, Palestinians tried to resolve the chaos through forceful and violent encounters between competing villages thrust together in the camps. Palestinians attempted to establish order through violence and might. Umbeck’s study of the California gold rush found that claims to valuable resources were established and protected through an individual’s ability to forcefully maintain exclusivity (1981, 39). Force or the use of violence served as a key tool to determine the initial distribution and protection of assets in the American “wild, wild West” (Umbeck 1981). In Palestinian refugee camps, this initial effort at establishing order through violent conflict was thwarted because no village was armed or powerful enough to establish dominance and maintain exclusive access to resources over the rest of the villages.

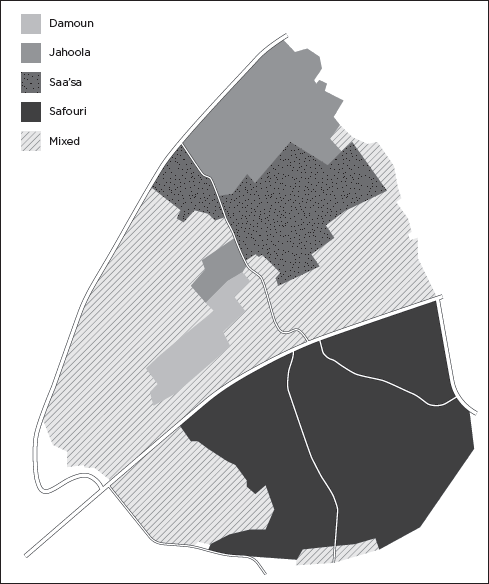

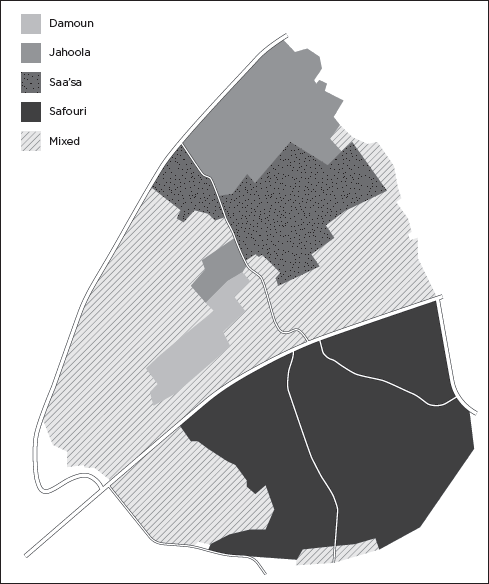

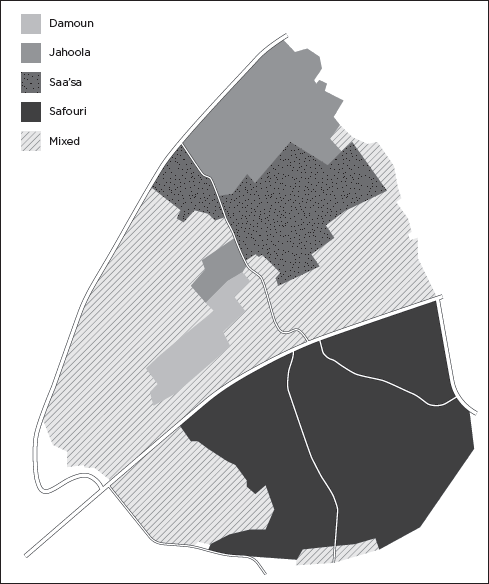

In Lebanon and Jordan, Palestinian refugee camps were grouped around pre-1948 villages. Old village dynamics and patterns of interaction were reproduced in the camps. “In this way many villages which the Israelis occupied, evacuated, and demolished in Palestine are still, socially speaking, alive and coherent units” (Sirhan 1975, 102). They have lost neither their social consciousness nor their family and village ties. The map of neighborhoods based on pre-1948 village origins depicts the communal geography in NBC camp in Lebanon. This official UNRWA document, created in 2007 to map pre-1948 villages in the camps, represents the patterns of groupings present in other camps. It shows that communities stuck together after 1948 for better or worse.

Though social cohesion is evident based on the physical structure of the camps, social conflict was not absent at the family or village level inside the camps. Old family and village feuds carried over into the camps. One resident summarized the early disharmony: “In the early years of chaos, there were conflicts over water usage, tent placement, tent size, divorces, and marriage matches” (I-91L).

These small conflicts sparked larger intra-camp battles. Villages sought to dominate each other and establish order in the camps. Camps historians in Lebanon and Jordan described the initial difficulty of agrarian communities moving to urban and congested living conditions with strangers from different villages. Initially, refugees did not feel that the refugee camp resembled a real community (I-91L). In the early 1950s, there was a lot of “social stress” among relocated Palestinian villages that were forced to live together in the same refugee camp (I-91L).

For example, different villages sought to dominate the camp. This prompted an internal camp “war” between the larger Safouri village and the smaller Saa’sa Palestinian village over land and space in NBC (I-91L). There were three battles along the shoreline of the camp. During battle, different villages were identified by the style of pantaloons or underpants that women wore into battle while fighting alongside men (I-91L). “Women would use their long skirts to carry rocks that family members would throw. Women with bell-shaped pantaloons came from Saa’sa village and women with tapered pantaloons were from the opposing village” (I-91L).

During battle, the women of Saa’sa chanted, “Oh, the One that helps the six beat sixty; give victory to the ones with the underpants like us!” Despite the three battles, there was no decisive victor and intra-camp relations were strained from the unrest (I-91L). Again, Umbeck’s (1981) theory of the formation of property rights through violence did not work in the refugee camps because no group was powerful enough to maintain exclusivity. There were similar intra-camp conflicts all over Jordan and Lebanon. The absence of a clear victor created even more disharmony and chaos for camp residents. In the case of the Palestinian refugee camps, the historical record suggests that there was roughly an equal distribution of power such that no single Palestinian village was powerful enough to dominate camp life and bring order to the community. This peculiarity of the community made it possible for a shared vision of property management to emerge rather than a model imposed by a powerful ruling family or village. A camp resident noted, “We learned that fighting with one another was not going to solve our problems” (I-24L). As time progressed, refugees agreed that a new model of community governance and protection should develop. A chief UNRWA information officer noted, “Initially there was conflict. In the course of time, it [the camp] turned into neighborhoods” (I-3J).

“CREATING GOLD” THROUGH HARD EFFORT

At the same time that the community realized violence would not create order in the camps, entrepreneurial Palestinians worked hard to grow their businesses in the difficult conditions of camp life. Young Palestinian men looked to the Gulf countries as a golden opportunity to earn money and build a better life for themselves and their families back in the camps (Brand 1988; Rubenberg 1983). In fact, Ghassan Kanafani’s famous short story “Men in the Sun” highlights the arduous desert journey and extreme lengths, including risking one’s own life, to which Palestinian men would go to make it to the Gulf. There was a strong communal norm that young Palestinian men working abroad would send the majority of their earned income to family members living inside the camps. Most young Palestinian men shared cramped apartments in the Gulf and Libya for many years to save money for their families. During interviews, business owners said that housing and building improvements were primarily financed by remittances sent by family members that worked in the Gulf or Libya. Residents revealed that the number one source of capital for investment came from remittance flows. Remittances gave Palestinian refugees the capital necessary to invest in a variety of camp resources. For example, an iron welder in Beddawi noted that he began his business in 1972 (I-11L). He earned the money to start the business by working in Libya for ten years from 1962 to 1972, where he also learned to weld and work with iron. When he returned to the camp, he used his remittance savings to marry, begin a family, and set up his iron welding and design business inside Beddawi. This pathway to business development was a common pattern in interviews.

Indeed, remittances were more important than UNRWA or Islamic bank loans in starting businesses (I-11L). Though such loans were theoretically available to Palestinian refugees, budget constraints and the high demand for loans made it impossible for most businesses to rely on UNRWA (I-2L). As a result, “most of the money that permitted refugees to initially invest in their homes and business in the camps came from remittances sent by family members” (I-2L).

The influx of money from remittances caused a surge in the demand for building supplies because people could finally afford to improve their tents to more permanent homes, as well as open businesses. Many refugees opened businesses on the bottom floor of their tent plot and then built homes above the stores (I-3J, I-21L). “Slowly, refugees demolished their huts and built new and better homes at their own expense” (I-3J). The typical refugee home sandwiches businesses with multigenerational levels of apartments extending upward. Usually the patriarch of the family lives directly above the store with his sons and their families occupying upper levels. It is not uncommon to find one small plot of land with a business on the ground level and four or five levels of apartment homes above it. Images of the camps today illustrate the texture of business growth in camps in Lebanon and Jordan. They depict the bustling markets filled with homes stretching upward and tangled wires powering progress in the camps.

In interviews, business owners said hard work was essential for their entrepreneurial success in a transitional space. “We have lived in dirt. But Palestinians knew that if we dug deep enough in the dirt, we would find gold. Our efforts created gold” (I-35J). In fact, the refugee economy became a central marketplace for neighboring Lebanese and Jordanian villagers to do business. The development of the Palestinian economy was quite remarkable given the dwindling aid and international assistance as the refugee situation persisted. The longer the protracted situation persisted, the more the overall budget for humanitarian aid assistance was repeatedly cut (Jacobsen 2005). With reduced aid, refugees had to create their own institutions to support themselves.

It is important to note that Palestinian refugees are not alone in their ability to create prosperity in a transitional space. There are many examples worldwide of refugee camps developing black market economies by selling humanitarian aid rations, engaging in small-scale enterprises, and working in the informal sector. For example, a study of the Kyangwali refugee settlement in Uganda noted that refugees achieved remarkable growth because of agricultural production, wage labor, small businesses, lending or investment schemes, and the trade of humanitarian rations (Werker 2007). Despite isolationist host country policies, refugees often traded non–food aid items such as clothes, household items, and construction materials at the local market for a profit. Refugees can sometimes get higher prices for “imported aid” products and can purchase cheaper local goods to replace the aid. In Semabkouya camp in Guinea, “Refugee small businesses get their start at the market by selling non-food items, particularly pots and blankets, as well as food rations. A full pot set and plates can bring as much as 18,000 GF. Replacement pots can be bought for as little as 9,000 GF, so this leaves a sufficient amount to invest in a new business” (Jacobsen 2005, 28).

Growth in the Palestinian refugee camps was assessed in several ways. For example, businesses were asked to provide basic information about the size and scope of their industry. A series of questions assessed industries in the camps: “What type of capital investments do you have?” “How many employees do you have (part-time and full-time)?” “Where do you do business or sell your products?”

The average business in Palestinian refugee camps across Lebanon and Jordan had at least three full-time employees other than the owner. Most businesses had part-time and seasonal laborers during busy times of the year. Construction business owners in the steel, tile, cement, carpentry, and glass businesses said they could hardly keep up with orders in the summer months. In addition, most owners had between $5,000 and $35,000 in personal capital investments in their businesses. In NBC and Beddawi camps, refugees also did business with clients outside the camps in the northern region of Lebanon. Some businesses even contracted with clients in Beirut. In Jordan, refugee businesses often did business with neighboring Jordanian markets. One respondent said, “For example, in Baqa’a camp there are roughly 86,000 people. There are lots of shops too, maybe 1,000 or 2,000. UNRWA had nothing to do with it. Neither did Jordan. They [the Palestinians] formed it on their own” (I-2J). Another said, “Businesses in Jordan were initially mom and pop style. They were rudimentary. But over time they evolved” (I-3J). Though navigating the markets was hard, most refugee businessmen agreed that “business was pretty good, even as a refugee” (I-2J).

A DYNAMIC RESPONSE TO CHAOS

Despite the increasing wealth inside the camps, there was still no system of order to protect community assets. An ice cream cone manufacturer said, “There was no organization inside the camps, especially for businesses. Everyone is his own boss. It was fawdah (anarchy). We needed a government to organize us” (I-8L).

UNRWA, Jordanian, and Lebanese policies of not governing the camps meant there was no government to create order inside the camps (I-3J). Moreover, attempts by villagers inside the camps to dominate through violence or force had proved ineffective. New Institutionalists might have predicted that Palestinians would have given up and gotten “locked into” the conditions of despair inside the camps because there was no credible third-party enforcer to build property rights.

But Palestinians were not paralyzed by the chaos and despair inside the camps. As Thelen (2004) suggests, individuals respond to conditions on the ground and readjust or shift their behavior when building institutions. Graeber (2004) reiterated this point when he noted that groups living in anarchy would push for institutions that govern their community within the constraints of their older experiences and possibilities of their new conditions. They would work to protect the community from outside domination and chaos while maintaining their group identity (7). In Governing Gaza, Feldman (2008) identifies the ways in which Gazans found order even in the absence of a legal sovereign power, especially when it was a stateless region from 1948 to 1967. For example, she asserts that the daily mundane work of bureaucrats issuing rations, pushing paper, and serving basic needs kept stability during the periods in between new regime rules. She says that the “reiterative authority” of bureaucrats reproducing titles, documents, or mundane tasks for the Gazan community created a measure of order when there was no legitimate sovereign power (Feldman 2008, 16–17). It is the everyday work of everyday people who functioned in disaster to create stability and rule in Gaza.

Similarly, Palestinian refugees responded dynamically to shifting conditions inside the camps. They functioned in disaster in an effort to craft order in anarchy. Nascent business entrepreneurs and everyday camp residents looked for ways to bring order to the chaos. A chocolate factory owner described the transition from chaos to order through property rights: “Over time my business grew. I was selling chocolate all the way up to Beirut. I had set up a good market. The camps also settled down too with less violence. And I believe the American saying is true, ‘necessity is the mother of invention.’ So Palestinians created a system of order on our own” (I-12L). Another resident in Jordan said, “The hard conditions challenged us everyday. We were forced to be creative and create a system that worked for us” (I-4J). A teacher emphasized that “Palestinians were empowered to do for themselves. No one else will do it for us” (I-20L).

The informal system of property rights developed organically in the camps. For example, some refugees were able to save up enough money to rent homes in nearby villages, so they sold or gave UNRWA-allocated land plots to their

ahl or family members left inside the camps (I-3J, I-21L, I-47L).

2 In an informal manner, refugees bought, sold, and traded land plots with one another in Lebanon and Jordan (I-3J, I-47L). Refugees usually transferred property claims to their

ahl through verbal or oral agreements with other refugees (I-3J, I-21L, I-47L). Sometimes religious officials and family elders witnessed the oral agreements (I-47L). In the event of a conflict over ownership, they went to religious officials or visited the family to resolve the dispute. One refugee summarized how the system of informal property rights functioned: “There were no lines demarcating the homes and businesses on a map. They were invisible. But it was understood that there was a distinction between where ownership began and ended” (I-3J).

In interviews, I searched for the specific time when property rights emerged in the camps. I probed for a magical moment when the community gathered and agreed to a system of rules that would govern the ownership of assets in their camps. Through interviews I learned that there was no exact moment or specific date when a system of rules emerged. It was a nonevent. As Sugden (1989) asserts in his description of the spontaneous order of institutional formation, it is a rare thing for a community to gather and collectively decide rules of ownership for driftwood on a beach where people collect wood. He reminds us that one does not normally see two cars pull aside, confer, and then come to a decision on who gets to traverse a one-lane bridge first. According to Sugden (1989), rules pop up when they are needed. Moreover, rules that are easy to replicate, regardless of conditions on the ground, are more likely to emerge as well. They can develop consciously or subconsciously as the community pushes for order and protection.

CONVERTING PRE-1948 PRACTICES INTO INFORMAL PROPERTY RIGHTS

Sugden (1989) and other spontaneous order scholars assume that property rights will naturally develop around valuable resources because of a static body of shared group history in managing property rights. However, communities living in transitional settings face significant hurdles in organically developing informal property rights around valuable resources. Specifically, Palestinians from different villages were thrust into the same cramped refugee camps and forced to live together. There were lots of conflicts. Moreover, different communities had myriad historical experiences and village values or norms with respect to land tenure practices to draw upon. What parts of their group history could Palestinians use to inform the functioning of the informal property rights system in refugee camps across Jordan and Lebanon?

Under Ottoman rule, there were a variety of ways in which Palestinians could “own” property. Unfortunately, Western scholars and political activists (both Palestinian and Israeli) often used their own legal terminology to analyze practices in Palestine prior to the Nakbah. This has led many to erroneously claim “that at the date of the partition of Palestine (1947) ‘over 70 percent’ of it [Palestine] did not ‘legally’ belong to the local Arab population but to the British mandated power” (Kemal 2014, 231). Based on such an argument, it would seem unlikely for Palestinians in the refugee camps to have any experience in owning property. According to Kemal’s (2014) historical study of property ownership in Palestine, Palestinians did in fact have diverse experiences in land tenure practices.

The misleading interpretation of land tenure practices prior to the

Nakbah ignored traditions of the local population and the complex system of property ownership during Ottoman rule. Up until 1858, there was no obligation for Palestinians to register property claims with Ottomans (Kemal 2014, 231). Until that time, there were a variety of ways property could be classified. First,

mulk permitted owners to benefit from the possession and use of an asset. It was the closest notion to “private property” in the Western conception of the term. Deeds were usually registered in Islamic religious courts. This classification of property was usually found in urban city areas like inside the walls of Jerusalem. It was rare to discover areas of land considered

mulk in rural areas. British studies of Palestine during the mandate era found

mulk classifications to be “negligible” (Kemal 2014, 232). In contrast, 90 percent of the surface area of the Ottoman Empire was owned by the state (

miri) and distributed for usufructure (

tassaruf) in exchange for a tax on production. As such,

miri property was not “privately owned” in the Western sense, but it was not “state-owned land” in the Western sense either because families that cultivated the land could sell their usufructury rights and pass those rights to their children. “State land, in the modern sense, is land that the state wishes to keep out of individual use, such as forest land. Such a legal category did not exist in the Ottoman Empire and came into being only in the new states.

Miri land was not state land in this sense. There was never really a question of usurpation of such land; at the most it could be misused” (Kemal 2014, 232–33).

Furthermore, there were many areas of land that were classified as

miri but designated as collective land holdings or

musha to tribes, large families, and villages. “On the eve of the First World War it is estimated that around 70 percent of agricultural land in Palestine fell under this [

musha] category” (Kemal 2014, 233). Families shared ownership of

musha land in rotation with the village. The rotation in ownership might occur every one, two, or five years so that every farmer would have a chance to cultivate fertile land (Kemal 2014, 233). There were other categories of land holding like

waqf, in which property was managed by pious Islamic foundations and used for the Muslim community. These lands fell outside the jurisdiction of Ottoman rule. In addition, there was

mawat land that was owned by the state but not cultivated. It was considered “dead” land that was not suited for cultivation and was located far away from villages. Often this land was used for grazing purposes (Kemal 2014, 233–34). Many historians argue that this land was probably “owned” by Bedouin communities. In addition, there was

matruka land designated for public use. It could be used for roads, irrigation canals, rivers, or forests. Finally, there was

jiftlik land located in the Jordan Valley that was held in the name of the Ottoman sultan. Suffice it to say that there was a complex entanglement of Ottoman and local cultural understandings of land ownership practices that Palestinian refugees could draw upon. It is not immediately clear which set of rules or practices they would draw upon to face the chaotic conditions in the refugee camps.

In Rediscovering Palestine: Merchants and Peasants in Jabal Nablus, 1700–1900, Beshara Doumani (1995) traces patterns of land ownership and economic growth in Palestinian communities under Ottoman rule. Doumani (1995) asserts that Palestinians in the Jabal Nablus region were no stranger to commercial agriculture, proto-industrial production, sophisticated credit relations, and commercial networks. During Ottoman times, most agricultural land in Palestine was state owned or miri. However, Palestinians did have “usufruct right as long as they did not allow these lands to lie fallow for more than three years. The right of use had no time limit: the land could be and was passed down through inheritance for generations. In return for its use, [Palestinian] peasants paid taxes (such as ushr, or tithe) that were levied both in cash and kind, plus a whole range of exactions” (Doumani 1995, 156).

Doumani further points out that peasants treated these lands as though they owned them privately. Over the centuries, each

ahl and

hamula became identified with particular lands, which they treated as private property. Moreover, court cases registered in the eighteenth and nineteenth century show that “peasants of Jabal Nablus did indeed dispose of nominally state lands as if they were private property by mortgaging, renting, or selling their usufruct rights” (Doumani 1995, 157). For example, a court case from May 29, 1837, demonstrated how Palestinian peasants treated the property as if it were privately owned when they sold land to others:

Today, Yusuf al-Asmar son of Abdullah al-Jabali from the village of Bayta appeared before the noble council. Being of sound mind and body he voluntary testified…that he ceded, evacuated, and lifted his hand from the piece of land located in Khirbat Balata…to the pride of honorable princes, Sulayman Afandi son of…Husayn Afandi Abd-al Hadi. [The latter] compensated him 700 piasters…and the aforementioned Yusuf Asmar gave permission to Sulayman Afandi to take over the piece of land. (Doumani 1995, 157–58)

After decades of Ottoman and British colonial rule, Palestinian refugees had complex understandings of how property ownership should and could be defined and enforced. This assertion is further supported by interview data that assess the historical origins and community knowledge of pre-Nakbah land ownership practices. I asked refugees to trace if and how historical experiences and religious values informed the practice of property ownership in the early years inside Palestinian refugee camps. In addition, the data highlight the desire for protection from elite predation and preservation of Palestinian identity among community members.

In interviews refugees were asked: “Did you own land, a home, or a business in Palestine? If yes, how did you claim ownership? Were you familiar with writing contracts or having documents that signified ownership before you arrived in the refugee camps?” In addition, refugees were invited to recount their family history of land ownership in Palestine. Every refugee interviewed had some sort of “proof” that they once owned land and farms in Palestine. A few had old titles outlining property ownership.

Though my interview data indicate that the majority of refugees felt they owned land in Palestine prior to 1948, there is significant disagreement over the actual percentage of refugees that “owned” land. In 1951, the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine (UNCCP) undertook a major study “to determine the scope and value of the property abandoned by Palestinian refugees in Israel” and to develop specific procedures for compensating refugee losses (Fischbach 2003, 114). John Berncastle, a British land expert, was tasked with leading the UNCCP study and estimated abandoned property based on British documentation of village statistics dating from 1945. Notably, he did not consult refugees in camps when he arrived at the number of abandoned properties. He found that 40 to 50 percent of Palestinian peasant land was not “owned” by the peasants themselves and likely belonged to elite Palestinians (Fischbach 2003). Taking this perspective, refugees had a very small claim of ownership in property in Palestine prior to 1948.

However, the historical record is more complicated than the UNCCP and Berncastle’s findings. Sami Haddawi, “the premier Arab expert on land in Palestine” due to his extensive experience with the British Department of Land Settlement in Palestine from 1919 to 1927, floated much higher estimates of Palestinian ownership and losses (Fischbach 2003, 213). Haddawi believed British tax assessments were too low because at the time there were only four persons that actually inspected property for all of Palestine (Fischbach 2003, 214). Haddawi felt that they rarely did a careful and accurate assessment of land and capital. Izzat Tannous, another contemporary of Berncastle and Haddawi, operated the Arab Refugee Property Owners in Palestine and his organization suggested “impossibly high” figures of ownership (Fischbach 2003, 215). These examples indicate the conflicting and politicized “official” accounts of how much property Palestinian refugees owned. Though this debate is interesting, from the perspective of my study, whether or not Palestinian refugees really “owned” the land in the

Western sense of the word is less important. It is most important that Palestinian refugees had experience buying, selling, and renting land or capital prior to 1948. Their pre-1948 experiences informed patterns of property ownership in the chaotic conditions of the refugee camps. In interviews, some refugees explained how their village owned the land collectively as

musha and how it was individually cultivated:

My family owned olive groves in Palestine. We lived in Samoie village close to the bigger city of Safad. We were a big family and we all lived close to each other. We had farmed this land for as long as anyone can remember in our family history. Before 1948, I can remember falling asleep as a boy to the sound of rumbles of the olives dropping onto ground during the harvest season. My Mom and the other women would press the olives together to make oil. She would also make olive soap for us to wash with. Some of the olives were preserved in oil for us to eat later on. I don’t have a title today to show for it. We certainly “owned” it by Ottoman standards of miri or musha because we cultivated it. (I-96L)

Refugees also highlighted how they had been dispossessed from their own land. For example, one resident said, “I have lived in the camps for fifty six years, since 1948. I have the title to my home in the camp. But my home is originally in Palestine, in a village called Um-al-Faraj, near Aqaar in Palestine. I still have my documents that show ownership of our home and farm there. It is important, even until today. You need rules to keep you safe” (I-23L). “I have my keys to my old home in Palestine. I also have the Ottoman document showing what I owned in Palestine. I learned, long ago, that you need to show you own your home for protection” (I-52L).

In summary, Palestinian refugees had a deep reservoir of knowledge and experience in managing and defining ownership of property. In addition, they were comfortable operating in ambiguous or, at the very least, confusing political economic landscapes. Navigating the maze of Ottoman land tenure classifications, Ottoman courts, Islamic religious courts, and British council administrators during the mandate era unexpectedly prepared them for the chaos, legal ambiguity, and “protection gap” they would confront in the Palestinian refugee camps across Lebanon and Jordan.

STRATEGIC SELECTION OF PALESTINIAN PRACTICES

Given the myriad experiences Palestinians could draw upon to develop rules of ownership in the camps, how did Palestinians organically decide to manage property rights in an informal manner after their arrival in the refugee camps? In his study of stateless tribes, Scott finds that a shared identity, whether really shared or strategically crafted, became “the political structure of rule…. It became the recognized way to assert a claim to autonomy, resources, land, trade route, and any other valuable that required a state-like claim to sovereignty” (Scott 2009, 258–59). Again, whether or not these community histories were in fact really shared by the entire community or strategically developed accounts of pre-1948 life is unimportant. The ambiguity and porousness of the community’s history was a political resource crafted to meet the challenges of life in a “fractured” or transitional zone (Scott 2009, 258). In the absence of a state and an established judicial system like the Ottoman courts, Palestinians resorted to pre-1948 community practices to informally govern property in the camps.

As a researcher, it was difficult for me to comprehend how Palestinians could not identify the exact moment they developed informal rules of ownership, thereby relegating rule adoption to the realm of spontaneous generation, and still discuss in interviews how certain pre-1948 village practices and values were carefully curated to meet the challenges of refugee camp life, thereby emphasizing the strategic choice behind rule adoption. Drawing upon the work of spontaneous order scholars, I believe one of the keys to understanding how rules organically

and strategically developed is based on Sugden’s (1989) discussion of the “ease of rule replicability” as the governing principle for norm adoption with respect to valuable assets. Sugden suggests that rules for defining and enforcing property will develop and persist if they are easy to put to use. Axelrod’s (1984) study of the evolution of cooperation in simulated computer games emphasizes a similar notion of the evolutionary advantages for cooperation rather than conflict. Scott also picks up on this intellectual thread when he talks about the “adaptive value” of certain community behaviors. Over time, “as one identity became increasingly valuable and another less so,” communities would be expected to adapt to the more valuable practice or identity (Scott 2009, 249). In summary, Palestinians tried a variety of strategies like the violent conflicts in the early refugee camps years, but found that pre-1948 community practices that emphasized cooperation through kinship and values of honor and shame were easier to use and therefore adopted.

Farsoun and Zacharia (1997) and Nadan (2006) identify pre-1948 Palestinian village practices for governing the rural economy during the Ottoman era and the British mandate period. He argues that patrilineal structures of kinship linked community members in real and imagined ways. These connections created the bedrock of community trust that governed political and economic transactions in the absence of a state or outside authority (Nadan 2006, 196). The central identifying patrilineal units of the Palestinian village were one’s

ahl or family and their

hamula, a broader association embodying many families much like a patrilineal clan or tribe (Farsoun and Zacharia 1997, 23; Nadan 2006, 197). These units were both genealogical and imagined, meaning someone could be

like a cousin or brother though not share blood lines. The

hamulas regulated and guaranteed “access to productive lands and the rights of individuals over them” (Farsoun and Zacharia 1997, 23). In effect, if everyone could be your brother or cousin or potentially a second or third cousin through marriage, one would not dare to dishonor and shame the family in communal dealings over property ownership and protection. An old Arab proverb highlights this way of thinking: “Me and my brother against our cousin, and me and my cousin against the stranger.” Patrilineal kinship ties anchored norms of behavior with respect to property ownership and conflict mediation. In sum, “patrilineal understandings [of ownership] were not signed in the manner of official contracts, as this would be regarded as shame or

‘ayb” (Nadan 2006, 196). The power of shame and honor in communities meant that informal handshakes were enough to enforce good behavior even in the absence of state authority.

For example, Nadan (2006) found that the Palestinian farmers or fellahin preferred to barter rather than push for cash transactions. “The village barber, for instance, was paid in kind for his services one a year at harvest time, and a carpenter would receive measures of wheat in return for maintenance of plows and for other work” (Nadan 2006, 174). Palestinians in the same community trusted that they would be paid, sometimes many months after an exchange, because they shared kinship ties.

Ahl and hamulas also protected individuals and kin during external conflicts. “Led by their own sheiks or religious leaders, the hamulas therefore provided the individual within the nuclear family collective protection in all aspects of his or her life,” especially during times of transition with new regimes and imperial powers seeking dominance (Farsoun and Zacharia 1997, 23). These pre-1948 village practices indicate that Palestinian refugees in Lebanon and Jordan, mostly hailing from the same rural places Nadan (2006) and Faroun and Zacharia (1997) studied, would have an easily replicable blueprint of kinship ties that embedded notions of honor and shame to anchor transactions in the chaos of the refugee camps.

In interviews Palestinian refugees emphasized how pre-1948 community codes of behavior anchored the enforcement of property rights. The owner of a glass business in Baqa’a camp explained, “There are strong religious and community values that are very traditional here. It makes protection an easy thing for us” (I-12J). Another said, “I trust in God and my neighbors to protect my home and business” (I-47L). A carpenter in Baqa’a camp said, “I rarely encountered problems [stealing, expropriation] with my business in the camp because we have strong Palestinian values. It is shameful to your family if you did these things. Everyone would know your reputation was ruined if you behaved that way” (I-9J).

Though the system of property rights lacked a judicial system to enforce rules, the community adopted rules that emphasized values of honor and shame. They were easy to use because they required little physical infrastructure and planning to create or use. It simply required social policing or community vigilance. There were high reputational costs for one’s family if one engaged in bad behavior that trampled on the property of others. A sheikh underscored the importance of a family’s reputation inside the camps” “If one’s family name was tarnished it influenced the ability of people to marry well and conduct future business in the area. A bad event had implications for future generations in your family” (I-79L). The power of informal rules was also emphasized in an interview with a Palestinian working for UNRWA: “If Nahr al-Bared camp were a Lebanese village, they would have much more crime. But they don’t. They don’t fight that much. It is because they have strong traditional values for protection” (I-5L).

Of course, like any community, there were communal conflicts and petty crimes, but for the most part refugees felt safe among their community in refugee camps because strong values of honor and shame anchored their communal behavior. Though Palestinians had many options to govern property in the camps, refugees adopted informal rules that emphasized community values that promoted cooperation through shared ideas of honor and shame. These rules were adopted because they were easy to put into practice in a transitional space.

The informal system of rules was far from perfect. Sometimes a transgression created an unending cycle of violence between families (I-79L). “Blood feuds could erupt when the community could not come to a solution over a problem” (I-79L). Informal rules could be terribly inefficient to enforce. At times “certain families were able to sway decisions in their favor compared with other less influential (or large) families” (I-54L). It is not my intention to present a utopian ideal of the early years in the camps. Far from it, the first couple of decades in the camps were messy and hard. They were filled with

fawdah or chaos. Despite the difficulties, Palestinian entrepreneurs slowly grew businesses and residents improved their homes. In addition, they spontaneously created informal rules that were patterned on community values of cooperation through honor and shame.

Palestinian norms of doing business and conducting behavior in social, economic, and political spheres were encoded in these informal property rules inside the camps. In a transitional landscape where every aspect of a refugee’s existence is threatened, this uniquely Palestinian set of rules is a powerful way of transmitting the community’s identity in the face of outside threats. In the upcoming chapters I discuss the preservation of the community from state incorporation as new threats confronted Palestinian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon and how it becomes an important motivating theme in negotiations over formal property rights with outside political groups.