Chapter 8

John 4:1–42

Literary Context

The narrative thus far has centered upon how the beginning of Jesus’s ministry fulfills and surpasses Judaism: 2:1–11 (true purification), 2:12–25 (true temple), 3:1–21 (true birth), and 3:22–36 (true baptism and witness). The previous pericope brought to conclusion an inclusio the narrative had created around the witness of John the Baptist, serving to highlight the nature of Jesus’s ministry coming out of the OT and entering directly into the Second Temple Judaism of his day. The scenery has now changed, as Jesus moves not merely beyond Jerusalem (cf. 3:22) but also beyond “Israel,” that is, Judaism. The Creator of the world has not merely come to his creation; he is moving through it. In this scene, the same Jesus is in one sense confronting a very different opponent (a Samaritan woman) from a very different context (non-Jewish/pagan). In another sense, however, Jesus is confronting the very same opponent (humanity) from a very familiar context (a world in darkness).

- III. The Beginning of Jesus’s Public Ministry (2:1–4:54)

- A. The First Sign: The Wedding at Cana (2:1–11)

- B. The Cleansing of the Temple: The Promise of the Seventh Sign (2:12–25)

- C. Nicodemus, New Birth, and the Unique Son (3:1–21)

- D. The Baptist, the True Bridegroom, and the Friend of the Bridegroom (3:22–36)

- E. The Samaritan Woman, Living Water, and True Worshippers (4:1–42)

- F. The Second Sign: The Healing of the Royal Official’s Son (4:43–54)

Main Idea

In the person of Jesus, the entire world is confronted with the inadequacy of its resources and the overabundant riches of the gift of God, which is international in scope and cross-cultural in character. It is at each person’s place of need, where they hunger and thirst, that God seeks and satisfies them with a food and drink no one could have imagined, rooted in the divine mission of the Trinitarian God. The appropriate response to God can be nothing less than true worship.

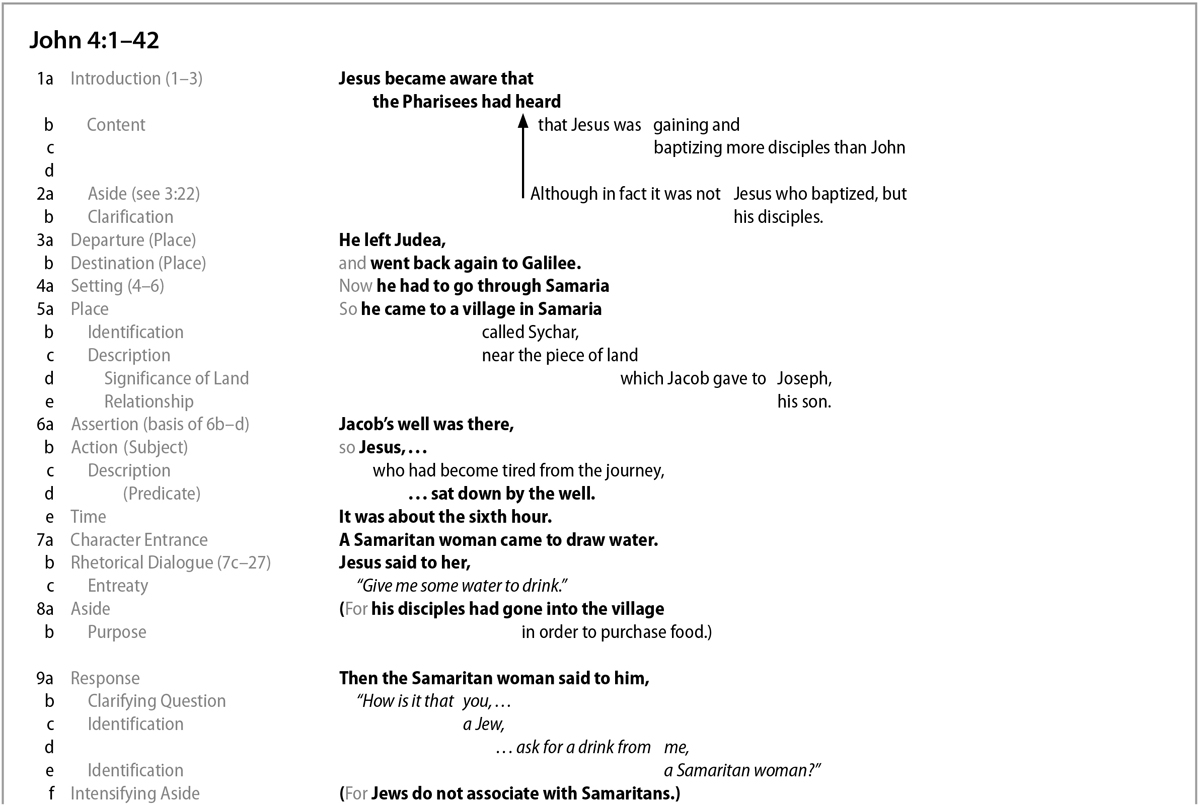

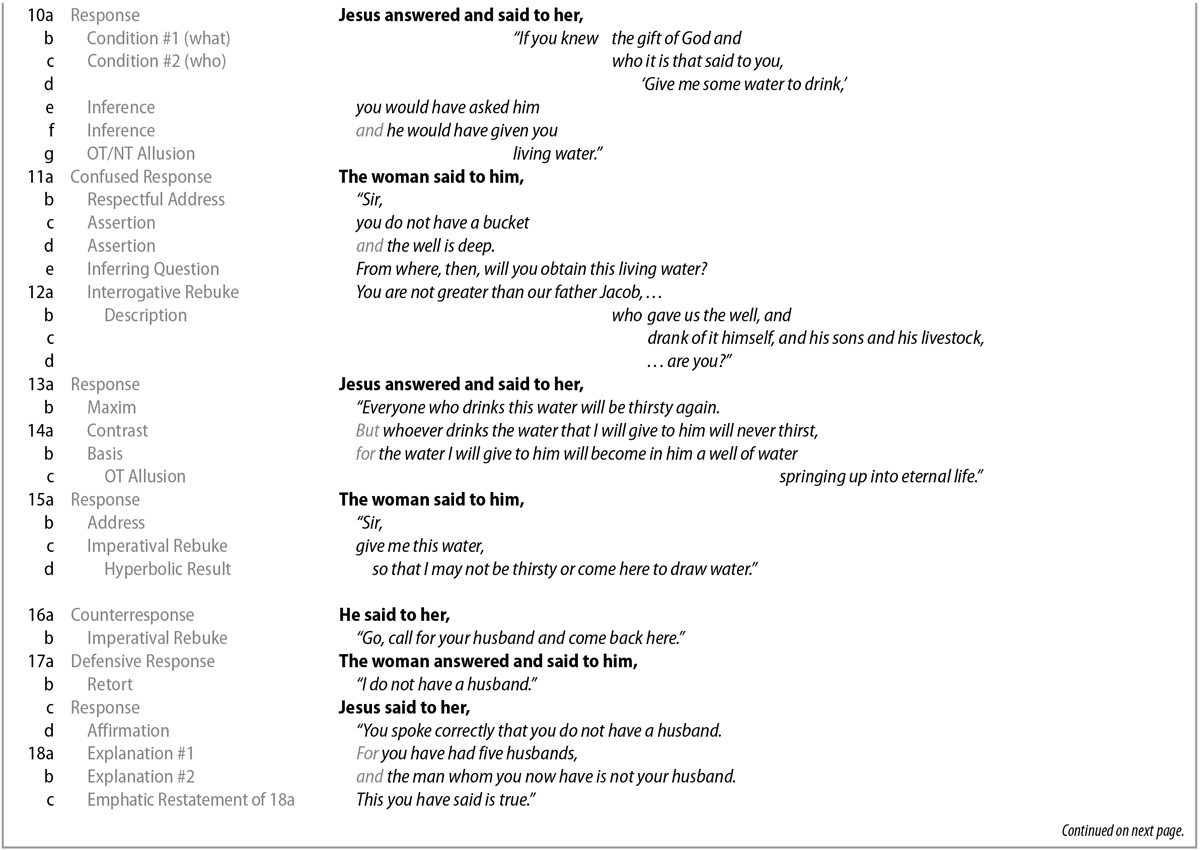

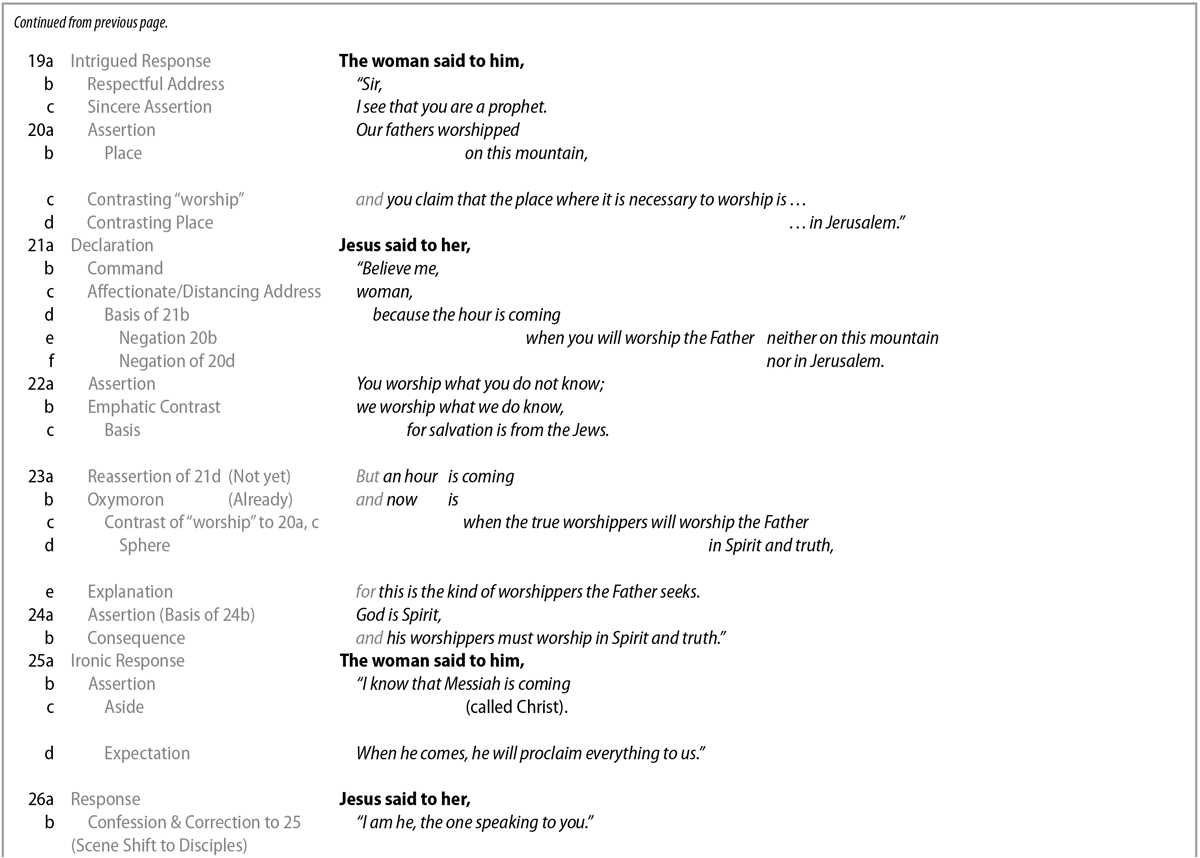

Translation

Structure and Literary Form

This is the second substantial dialogue in the narrative proper, and it is a rhetorical challenge dialogue, which takes the form of a creative discussion of antitheses rather than a challenge or conflict over an exchange of ideas. A rhetorical challenge does not intend to advance an argument but to intensify conflict between two parties that have already agreed to disagree. The goal is not invitation but exclusion (see Introduction). It is in the form of a rhetorical challenge dialogue that the plot of the Gospel advances, especially as the reader takes into account the larger literary context.

Exegetical Outline

- E. The Samaritan Woman, Living Water, and True Worshippers (4:1–42)

- 1. Jesus’s Return to Galilee through Samaria (vv. 1–6)

- 2. First Verbal Exchange: Jesus’s Provocative Request for Water (vv. 7–9)

- 3. Second Verbal Exchange: “Living Water” (vv. 10–12)

- 4. Third Verbal Exchange: Well of Eternal Life (vv. 13–15)

- 5. Fourth Verbal Exchange: The Woman and Her Husbands (vv. 16–18)

- 6. Fifth Verbal Exchange: True Worship and Worshippers (vv. 19–24)

- 7. Sixth Verbal Exchange: The Confession of Christ (vv. 25–26)

- 8. Interlude: Jesus’s Disciples, True Food, and the Harvest (vv. 27–38)

- 9. “The Savior of the World” (vv. 39–42)

Explanation of the Text

It has been common for interpreters to construct a controlling motif of a betrothal scene that, much more than an “impression” (see Introduction), is viewed as a technical “type-scene” taken from the Old Testament. Since 1981, Alter’s detection of a “betrothal type-scene” in biblical narratives has had an overwhelming effect on the interpretation of the dialogue between Jesus and the Samaritan woman.1 Although some of Alter’s thesis is helpful in its analysis of this pericope and supports the wedding (2:1–11) and bridegroom (3:29) imagery that has already been made explicit, its imposing presence has raised more than a few problems. First, while there are several “betrothal” images that Alter and others have been right to notice, the motif cannot be determined or applied exegetically with anything close to certitude.2 Second, the methodological concerns mentioned above are ultimately a problem with the betrothal type-scene construct itself. The error began with Alter, who wrongly clustered the biblical narrative repetitions of betrothal into a technical type-scene.

Helpful here is Arterbury, who argues that even ancient exegetes read the OT narratives that Alter cites not as depictions of betrothal but as depictions of the ancient custom of hospitality.3 The ancient customs Alter recognizes as a pattern in the OT texts, including some aspects of betrothal, take place within the broader social context of hospitality. Alter overemphasizes the male/female relationship in those texts and misses the more central host/guest relationship emphasized by ancient authors. He also makes a “grossly exaggerated” link between wells (water) and betrothals, when references to travelers stopping at wells for assistance in ancient hospitality narratives are commonplace, and he misplaces the necessary link between hospitality and betrothal, with the latter serving as a subset of the former.4

This commentary, therefore, will argue that the motif (or “impression”) controlling the dialogue between Jesus and the Samaritan woman is not a technical type-scene of “betrothal” but the more general concept of “hospitality,” and that this controlling motif plays an important role in giving definition to the rhetorical challenge dialogue.5 We suggest that the larger social category of hospitality, a recognized Mediterranean custom in ancient cultures, is guiding the reader in John 4 (see especially comments on vv. 23 and 40). Rather than emphasizing the male/female dimension central to betrothal, hospitality emphasizes the narrative’s explicit tension, that is, the host/guest tension between a Samaritan and a Jew (and ultimately the host/guest tension between the world and God). The focus is less on the male/female relation and more on the identity of the guest and the responsiveness of the host. The social context of the scene provides for an ironic twist. The innate tension between a Samaritan and a Jew, traditionally reinforced by means of a rhetorical challenge (an encounter), has morphed into a demand for hospitality between a host and her guest. Yet a grand irony takes place in this strange, tension-filled encounter, when the supposed host (the Samaritan woman) becomes the surprise guest before the generous hospitality of the true host (Jesus).

4:1 Jesus became aware that the Pharisees had heard that Jesus was gaining and baptizing more disciples than John (Ὡς οὖν ἔγνω ὁ Ἰησοῦς ὅτι ἤκουσαν οἱ Φαρισαῖοι ὅτι Ἰησοῦς πλείονας μαθητὰς ποιεῖ καὶ βαπτίζει ἢ Ἰωάννης). Because Jesus has moved from the Judean countryside to Samaritan territory (3:22; 4:4), the narrative gives a brief introduction to the scene change in vv. 1–3. Some commentators separate this introduction from the rest of the pericope or consider it to be an editorial insertion intending to make sense of the change in venue.6 But the reoccurrence of the Pharisees is not an awkward intrusion but serves to highlight the plot’s continual interest in Jesus’s opponents, who in this case appear to be watching and taking note, even if from a distance. If the Pharisees took great interest in the work of the Baptist (cf. 1:19, 24), how much more the activities of Jesus, who not only had recently cleansed the temple and survived the challenge with Nicodemus but was now the greater threat, gaining and baptizing more disciples than John (cf. 3:26). This comment, therefore, connects this pericope with what has come before, moving the plot forward. By reminding the reader of the larger conflict between Jesus and “the Jews,” the encounter with the Samaritan woman serves as an ironic twist: the further Jesus moves from Jerusalem, the less combative are his encounters.

4:2 Although in fact it was not Jesus who baptized, but his disciples (—καίτοι γε Ἰησοῦς αὐτὸς οὐκ ἐβάπτιζεν ἀλλ’οἱ μαθηταὶ αὐτοῦ—). In an aside, the narrator makes clear that Jesus did not perform the baptisms; his disciples did. For a full discussion of the meaning of this verse and the important clarification it makes, see the comments on 3:22. Its occurrence here and not in 3:22 is to ensure that the reader is aware that the Pharisees’ interest in all unapproved religious activities has centered entirely upon Jesus, under whom all his disciples are actively ministering (John and his disciples included). Even the “revival” work taking place in Judea (3:22) and involving a large-scale ministry of the Baptist has been tied to the person of Jesus, who is no longer in Judea but in Samaria (vv. 3–4).

4:3 He left Judea, and went back again to Galilee (ἀφῆκεν τὴν Ἰουδαίαν καὶ ἀπῆλθεν πάλιν εἰς τὴν Γαλιλαίαν). What is often the first information given regarding the context is reserved for the end of the introduction to the new scene. Although v. 1 explains that Jesus left Judea for Galilee after he heard about the Pharisees, we are given no details regarding the specific concern(s) Jesus might have had or the reason for his departure. Certainly there is nothing in the narrative that suggests that he was “troubled” by this knowledge and took flight “to avoid the Pharisees’ questions.”7 If he were trying to avoid conflict, he had failed to do so at this point in the Gospel. A clue to Jesus’s departure might be implied by the word “left” (ἀφῆκεν), which normally carries the meaning “abandoned” (cf. v. 28 in regard to the woman’s waterpot). Such a move is an abandonment of Judea, a temporary but vivid rebuke of his opponents, who after several encounters are only growing in their darkness-filled reproach of the light.8 What had begun in the outermost court of the temple, the court of gentiles (cf. 2:14), was now taking place in the land of the gentiles, in Samaria. This was the kind of tangent or coincidence that is grafted quite naturally into the original plan of God.

4:4 Now he had to go through Samaria (ἔδει δὲ αὐτὸν διέρχεσθαι διὰ τῆς Σαμαρείας). Since the route normally followed by Jewish travelers heading north from Judea to Galilee passed through Samaria, Jesus “had” (ἔδει) to go through Samaria. Interpreters are often split between viewing this verb as expressing personal convenience (the shortest route from Judea to Galilee) and divine compulsion (the divine will for Jesus). Those that look to Josephus to support the view that the shortest route was through Samaria (Ant. 20.118; J.W. 2.232; Life 269) often ignore the context of his discussions, which involve the pilgrimage to Jerusalem (not from Jerusalem) for religious reasons.9 The Gospel has already made clear that the activities of Jesus are founded upon something greater than circumstance (cf. 2:4), and the term “had” (ἔδει) is particularly important in John for the eschatological necessity of God’s plan, especially in regard to the saving work of Jesus (3:7, 14, 30; 9:4; 10:16; 12:34; 20:9). The Gospel has already used words as conceptual markers (see comments on 1:17). For the Fourth Gospel, therefore, the word “had” (ἔδει) connotes the cosmological mission of the Son and demands that the reader see the creative work of God in the world. In a very real sense, the OT and the developing mission of God explain that Jesus “had” to go through Samaria. Jesus is the Light to the world, the one through whom “all peoples on earth will be blessed” (Gen 12:3).

4:5 So he came to a village in Samaria called Sychar, near the piece of land which Jacob gave to Joseph, his son (ἔρχεται οὖν εἰς πόλιν τῆς Σαμαρείας λεγομένην Συχὰρ πλησίον τοῦ χωρίου ὃ ἔδωκεν Ἰακὼβ [τῷ] Ἰωσὴφ τῷ υἱῷ αὐτοῦ). Because he traveled through Samaria, he happened to come upon a certain “village” (πόλιν) in the region of Samaria. The most significant piece of information is the inclusion that it is “near the piece of land” (πλησίον τοῦ χωρίου) connected to Jacob. The importance of the mention of “Samaria” and “Sychar” was to highlight the geographical context; the mention of “Jacob” provides a different kind of map—it connects the place within the history of God and his people. The setting for this encounter is not merely first-century Samaritan soil but ground upon which God has been toiling for centuries. In this sense, the entire biblical story becomes part of the map for this scene.

4:6 Jacob’s well was there, so Jesus, who had become tired from the journey, sat down by the well. It was about the sixth hour (ἦν δὲ ἐκεῖ πηγὴ τοῦ Ἰακώβ. ὁ οὖν Ἰησοῦς κεκοπιακὼς ἐκ τῆς ὁδοιπορίας ἐκαθέζετο οὕτως ἐπὶ τῇ πηγῇ· ὥρα ἦν ὡς ἕκτη). The narrator situates the reader’s gaze more intently over the map of the biblical story by mentioning the presence of Jacob’s well. Though not mentioned in the OT, it was apparently known in the first century. The setting recalls three well-known biblical incidents in which a man met a prospective bride at a well: (1) when Abraham’s servant met Rebekah on behalf of Isaac (Gen 24:1–27), (2) when Jacob met Rachel (Gen 29:1–12), and (3) when Moses met Zipporah (Exod 2:15–21). This has led some interpreters to read the remainder of this pericope through the lens of a technical “betrothal” type-scene. But the images portrayed by the narrative are intending to “impress” upon the reader the larger map of the biblical story alongside the first-century cultural customs of hospitality.

The narrator gives the reason for stopping at Jacob’s well: Jesus “had become tired from the journey” (κεκοπιακὼς ἐκ τῆς ὁδοιπορίας). Such a statement provides a potent insight into the humanity of the Word-become-flesh. Jesus’s fatigue, however, does not merely fit into the timing and place of his rest but expresses the very essence of his mission. The mission of the Son is not merely reflected in where he goes and what he says but even in what he endures.13 “It was about the sixth hour” (ὥρα ἦν ὡς ἕκτη), which suggests it was around noon. In light of the map of the biblical story suggested above, the setting of this scene creates a powerful image. In the middle of the day, on soil upon which God had already worked, the Christ sat at the well of Jacob. The sun of the day was beating down on the Son, who himself is light in a world that is overtaken by darkness. As much as this “piece of land” was significant for the Jewish people, the impending encounter would make this property significant to the whole world (v. 42).

4:7 A Samaritan woman came to draw water. Jesus said to her, “Give me some water to drink” (Ἔρχεται γυνὴ ἐκ τῆς Σαμαρείας ἀντλῆσαι ὕδωρ. λέγει αὐτῇ ὁ Ἰησοῦς, Δός μοι πεῖν). A woman who is a native of the region of Samaria came to the well upon which Jesus rested. “Samaritan” (ἐκ τῆς Σαμαρείας) is to be understood as functioning adjectively with “woman” (γυνὴ) and is not to be locating her from the city of Samaria, which lay several miles to the northwest.14 It is all but certain that by mentioning the region of Samaria as the origin of this woman and not her particular village, the narrator is imputing to her all the vitriol properly basic to the broken human relations between her people and the Jews. This unnamed woman is known only by her origin from an enemy people.

When used for a request rather than a command, the aorist imperative, “give” (Δός), is best taken as a polite command. Even though the imperative is spoken by a superior to an inferior, as in this case from a Jewish male to a Samaritan woman, the context serves to soften the command.15 It is not just the tone of the statement that is interesting, for as the dialogue will reveal the request is surprising at numerous levels. But the dialogue has begun, and Jesus has initiated it with the Samaritan woman.

4:8 (For his disciples had gone into the village in order to purchase food.) (οἱ γὰρ μαθηταὶ αὐτοῦ ἀπεληλύθεισαν εἰς τὴν πόλιν, ἵνα τροφὰς ἀγοράσωσιν). Although the larger religious and social context of the encounter between Jesus and the Samaritan woman had already been established by the narrative, an explanation was needed regarding why the request was made to the Samaritan woman and not to one of Jesus’s disciples, which would have been normal practice for students of a teacher in the ancient world. The narrator informs us that they had gone into the village to buy food. Thus, Jesus was left alone. Apparently the woman had come alone as well, even though it was likely that women more frequently went to gather water in groups. If her isolation is connected to a consequence of her public shame, as several interpreters have suggested, the narrative gives no indication (see vv. 16–18).

4:9 Then the Samaritan woman said to him, “How is it that you, a Jew, ask for a drink from me, a Samaritan woman?” (For Jews do not associate with Samaritans) (λέγει οὖν αὐτῷ ἡ γυνὴ ἡ Σαμαρῖτις, Πῶς σὺ Ἰουδαῖος ὢν παρ’ ἐμοῦ πεῖν αἰτεῖς γυναικὸς Σαμαρίτιδος οὔσης; [οὐ γὰρ συγχρῶνται Ἰουδαῖοι Σαμαρίταις]). Rather than rejecting directly the request, the woman seems to receive Jesus’s polite command and turn it back on his position as the superior with a clarification question that illustrates her surprise and serves as a cutting rejoinder.16 In a sense, the woman’s surprise at Jesus’s engagement with her serves to soften the nature of this rhetorical challenge. Although the surprise is ultimately rooted in the long-lasting conflict between Jews and Samaritans, to which the narrator’s comment adds further warrant, it is probably also based upon the fact that a man was speaking like this to a “Samaritan woman” (γυναικὸς Σαμαρίτιδος οὔσης), considered in rabbinic tradition to be the lowest of the low.17 The question and the narrator’s comment presuppose much of the tension between Jews and Samaritans we have already discussed (see comment on 4:4). The use of the term “associate” (συγχρῶνται) by the narrator does not merely refer to the history of strife between the two groups but is probably intended to include also the numerous particulars of ritual purity that separate Jews from Samaritans.18

4:10 Jesus answered and said to her, “If you knew the gift of God and who it is that said to you, ‘Give me some water to drink,’ you would have asked him and he would have given you living water” (ἀπεκρίθη Ἰησοῦς καὶ εἶπεν αὐτῇ, Εἰ ᾔδεις τὴν δωρεὰν τοῦ θεοῦ καὶ τίς ἐστιν ὁ λέγων σοι, Δός μοι πεῖν, σὺ ἂν ᾔτησας αὐτὸν καὶ ἔδωκεν ἄν σοι ὕδωρ ζῶν). Jesus receives the woman’s surprise and rejoinder and counters them both: the surprise is greater than you can imagine, and the response is the opposite it would be if you truly knew the one with whom you speak! Such a counter by Jesus bends the rules of the rhetorical challenge, as Jesus is only challenging her posture and not her party. It is through a rhetorical challenge that the mission of the Son becomes most clear, for only through Jesus can the “dividing wall of hostility” be broken (see Eph 2:14–18). Jesus’s counter is in regard to the misunderstanding of identity the Samaritan woman has raised. It is not that Jesus does not know who he is (and therefore is acting inappropriately); it is the woman who does not know who Jesus is—and she, therefore, is the one acting inappropriately. His identity is Jewish, and his appearance is one of a thirsty and helpless traveler; yet the truth is that he is the unique Son, the very expression of the love of God.

Jesus makes clear that she is unaware of “the gift of God” (τὴν δωρεὰν τοῦ θεοῦ). This mysterious phrase is given several possibilities by interpreters. The term “gift” (δωρεά) occurs eleven times in the NT and always denotes a “graciously offered” gift of God, four times with reference to the Spirit (Acts 2:38; 10:45; 11:17; Heb 6:4; cf. Acts 8:17–20).19 Since the Spirit was prominent in the previous pericope, it is likely that “the gift” includes the Spirit. Yet since the gift is “of God” (τοῦ θεοῦ), with the subjective genitive making emphatic that God the Father is the giver of the gift, then “the gift” is rooted in the Trinitaran identity of God. “The gift of God” is salvation (“eternal life”) culminating in the gift of the Spirit, given by both the Father who initiated this divine action and the Son who serves as the agent of this divine activity.20

The gift, however, is given more explicit definition by the phrase “living water” (ὕδωρ ζῶν). While several symbolic or metaphorical interpretations have been suggested, rooted in first-century climate,21 the phrase is clearly connected to the culminating work of God promised in the OT. A clear example is in Jeremiah 2:13, where the Lord brings a complaint against Israel: “My people have committed two sins: They have forsaken me, the spring of living water, and have dug their own cisterns, broken cisterns that cannot hold water” (emphasis mine). Significant here is that God is described as the spring of living water (cf. Jer 17:13; Ps 36:9). Yet even after rebuking the people for rejecting him, God offers hope: “The days are coming . . . when I will bring my people Israel and Judah back from captivity and restore them . . .” and “I will make a new covenant” (see Jer 30:3; 31:31–34). “In OT terms, this declaration is truly breath-taking: the people that had abandoned the very fountain of living water are promised a future superior to everything that Moses gave.”22 A similar declaration of restoration is given by Ezekiel. God will cleanse his people with “clean water” and will “put my Spirit in you” (Ezek 36:25–27). He will cause water to flow out of the sanctuary in the new Jerusalem to bring life to the dried-up land even beyond Judah’s borders (Ezek 47:1–12; cf. Zech 13:1; 14:8; Joel 2:28–29; 3:18). Such prophecy portrays the blessing of God that floods from Jerusalem into the surrounding countries—even the region of Samaria! And this blessing is not just rooted in the OT, for as Revelation 7:16–17 declares: “ ‘Never again will they hunger; never again will they thirst. The sun will not beat down on them,’ nor any scorching heat. For the Lamb at the center of the throne will be their shepherd; ‘he will lead them to springs of living water’ ” (emphasis mine). And Revelation 21:6: “He said to me, ‘It is done. I am the Alpha and Omega, the Beginning and the End. To the thirsty I will give water without cost from the spring of the water of life’ ” (emphasis mine).

Thus, the “living water” in the context of Jacob’s well on a sun-beating day is rest and satisfaction—eternal life—rooted in the Trinitarian God—Father, Son, and Spirit—and mediated by Jesus Christ, his person and work. It is inclusive of everything the prophets could foretell and the Apocalypse could describe. It is perfect provision from God, with God, and for God. It is what Calvin summarizes as “the whole grace of renewal.”23 Even in his human fatigue and thirst, Jesus was fully satisfied. It was the Samaritan woman, competent enough to gather water for Jesus, who was the one in true need.

4:11 The woman said to him, “Sir, you do not have a bucket and the well is deep. From where, then, will you obtain this living water?” (λέγει αὐτῷ ἡ γυνή, Κύριε, οὔτε ἄντλημα ἔχεις καὶ τὸ φρέαρ ἐστὶν βαθύ· πόθεν οὖν ἔχεις τὸ ὕδωρ τὸ ζῶν). The woman clearly does not understand the significance of the things about which Jesus spoke. The reason might be because “water” was such a common physical object that she did not think it signified anything more complex. Or perhaps she was unfamiliar with such a metaphorical/theological use of “water,” since the Samaritans did not accept the prophets as canonical. Whatever the reason, she is confused on two fronts: the logistics of obtaining the water about which Jesus speaks and, more implicitly, why he is offering her water when he began the encounter asking for it. Beyond her confusion, however, the woman addresses Jesus with a respectful title, “Sir” (Κύριε), which she will apply to him two more times with increasing respect (vv. 15, 19). Jesus has already bent the rules for what should have been a rhetorical challenge, and the woman seems to have noticed.

4:12 “You are not greater than our father Jacob, who gave us the well, and drank of it himself, and his sons and his livestock, are you?” (μὴ σὺ μείζων εἶ τοῦ πατρὸς ἡμῶν Ἰακώβ, ὃς ἔδωκεν ἡμῖν τὸ φρέαρ καὶ αὐτὸς ἐξ αὐτοῦ ἔπιεν καὶ οἱ υἱοὶ αὐτοῦ καὶ τὰ θρέμματα αὐτοῦ;). Even beyond the seemingly impossible retrieval of water about which Jesus speaks, the Samaritan woman notices that he speaks quite strangely about himself and what he can provide. She likely finds it ironic that he speaks in this manner as he rests on the very well of Jacob, a father claimed by both Jews and Samaritans (cf. Josephus, Ant. 11.341). The occurrence of “our father” (τοῦ πατρὸς ἡμῶν) is a turning point in the dialogue because the Samaritan woman has now found a topic agreeable to both parties.

With what is probably another cutting rejoinder, the woman chides Jesus not simply for forgetting his personal Jewish heritage (by speaking to a Samaritan), but for forgetting the roots of Jews (and Samaritans) as a whole. Her question assumes a negative answer, denoted by the use of “not” (μὴ), since it would be inconceivable for a person to consider themselves to be greater than the patriarchs. The negation is not merely denying that Jesus is anything like the great one of the past but also anything like the coming great one. Only one person in the Torah could fit this description, the one who after having “nothing to draw with” gave Israel “living water” at Rephidim (Exod 17:1–7) and Kadesh (Num 20:2–13), where “water gushed out, and the community and their livestock drank” (Num 20:11). The Samaritan woman is implicitly asking—even while disbelieving—if Jesus is the prophet like Moses (Deut 18:15–19).24 But the coming prophet would be great like Jacob; therefore it was worth pressing the past comparison: If Jacob drank from this well, as well as his sons and livestock, how is it that you find this well and its water inadequate?

4:13 Jesus answered and said to her, “Everyone who drinks this water will be thirsty again” (ἀπεκρίθη Ἰησοῦς καὶ εἶπεν αὐτῇ, Πᾶς ὁ πίνων ἐκ τοῦ ὕδατος τούτου διψήσει πάλιν). Jesus’s response is simple and the proof directly apparent: everyone who drank from this well—Jacob included—was never truly satisfied; shortly after drinking, they needed to drink its water again. By describing it with the emphatic “this water” (τοῦ ὕδατος τούτου), Jesus locates its purpose and therefore its limitation. “This water” is not the same as the water “I will give” (v. 14). Jesus already speaks past this moment and this day (and even physical water) to speak of the life that is to come.

4:14 “But whoever drinks the water that I will give to him will never thirst, for the water I will give to him will become in him a well of water springing up into eternal life” (ὃς δ’ ἂν πίῃ ἐκ τοῦ ὕδατος οὗ ἐγὼ δώσω αὐτῷ, οὐ μὴ διψήσει εἰς τὸν αἰῶνα, ἀλλὰ τὸ ὕδωρ ὃ δώσω αὐτῷ γενήσεται ἐν αὐτῷ πηγὴ ὕδατος ἁλλομένου εἰς ζωὴν αἰώνιον). Jesus had already shown the limitations of “this water” and Jacob’s well; it was time to describe the greater water that “I will give” (ἐγὼ δώσω). Unlike Jacob’s water, those who drink this water “will never thirst” (οὐ μὴ διψήσει εἰς τὸν αἰῶνα). The phrase translated as “never” (εἰς τὸν αἰῶνα) can also be translated as “into eternity,” but is usually translated as “indefinitely, always, forever,” or in this case with the negation, “never.”25 The emphasis is on permanent satisfaction from thirst.

Although he is speaking of “water,” it is not water found anywhere known to humanity. It is water “from God,” given only by Jesus Christ. This water is so potent that Jesus explains that it will plant itself in the person in such a way that they become the location in which it dwells—a well out of which this water will be “springing up into eternal life” (ἁλλομένου εἰς ζωὴν αἰώνιον). The participle “springing up” (ἁλλομένου), translated as “welling up” by the NIV, is used of quick movement by living beings, such as jumping (e.g., after being healed, cf. Acts 3:8), and is used nowhere else of the action of water. It can also be used to emphasize quick movement emanating “from a source.” Both nuances of the word can be connected to the Spirit, as well as its use in the LXX, even though no such indication is given here (see comments on 7:37–39). The emphasis here is that the “springing up” leads to “eternal life,” which is a central theme in John’s Gospel (see comments on 3:15). This is the fulfillment of what the OT has long foretold: “With joy you will draw water from the wells of salvation” (Isa 12:3) and “Come, all you who are thirsty. . . . Listen . . . and you will delight in the richest of fare. . . . Surely you will summon nations . . .” (Isa 55:1–5).

4:15 The woman said to him, “Sir, give me this water, so that I may not be thirsty or come here to draw water” (λέγει πρὸς αὐτὸν ἡ γυνή, Κύριε, δός μοι τοῦτο τὸ ὕδωρ, ἵνα μὴ διψῶ μηδὲ διέρχωμαι ἐνθάδε ἀντλεῖν). Unaware of both the specifics and the grandeur about which Jesus speaks, the Samaritan woman at least knows she wants this water. Her response to him, however, is likely a bit playful and probably also includes a chiding: “Hey dreamer, this water sounds good to me!” As attractive as his words sound, she is unable to see that to which he speaks. In her hands was an actual bucket, and her throat was dry; the thirst about which Jesus spoke was too ethereal—she was unable to see the Word behind the flesh.

4:16 He said to her, “Go, call for your husband and come back here” (Λέγει αὐτῇ, Ὕπαγε φώνησον τὸν ἄνδρα σου καὶ ἐλθὲ ἐνθάδε). With these words, Jesus began to touch on a topic that was hardly ethereal. It was part of the woman’s daily, tangible life and would serve as a handle for the remainder of the dialogue. Although she does not know or understand Jesus, he understands and knows her. Since the Samaritan woman had just uttered what is probably to be viewed as a closing retort, bringing the conversation either to a standstill or a conclusion,26 Jesus applies a new and strategic tactic—he makes the conversation personal. This tactic is not intended to shame the woman—what would have been expected in a rhetorical dialogue—but to draw her in and help her understand about that which he speaks. And this is “a remarkable example of his compassion—when she would not come to Him voluntarily he draws her almost unwillingly.”27

4:17 The woman answered and said to him, “I do not have a husband.” Jesus said to her, “You spoke correctly that you do not have a husband” (ἀπεκρίθη ἡ γυνὴ καὶ εἶπεν αὐτῷ, Οὐκ ἔχω ἄνδρα. λέγει αὐτῇ ὁ Ἰησοῦς, Καλῶς εἶπες ὅτι Ἄνδρα οὐκ ἔχω). While the woman was probably thinking Jesus strange up to this point in the dialogue and by her questions putting him on the defensive, her response here suggests she is now on the defensive. Her response, “I do not have a husband” (Οὐκ ἔχω ἄνδρα), was probably intended to thwart any further investigation. But Jesus quickly turns her defense tactic into his own strategy. He commends her for speaking correctly, though he changes her words so that “husband” (Ἄνδρα) is emphasized (moving it from last to first place in word order). Her life and her sin is exposed—which is exactly what the water of salvation was intended to quench: “On that day a fountain will be opened . . . to cleanse them from sin and impurity” (Zech 13:1).

4:18 “For you have had five husbands, and the man whom you now have is not your husband. This you have said is true” (πέντε γὰρ ἄνδρας ἔσχες, καὶ νῦν ὃν ἔχεις οὐκ ἔστιν σου ἀνήρ· τοῦτο ἀληθὲς εἴρηκας). Jesus presses her statement by emphasizing her husband, specifically the “five” (πέντε) husbands she has had, excluding the man to whom she is currently living with but not married to. The repeated emphasis on having said what is “true” (ἀληθὲς) or what is “correct” (καλῶς) in the previous verse serves to heighten her sensitivity to good judgments, to truth, to reality. Jesus has been speaking what is truth; he has been shining light in a dark place. In this moment, he was shining his light into the darkness of a woman’s soul.

The exact sin of the woman must be extracted carefully. The verse says nothing about her being a prostitute, as is commonly assumed. If anything, the opposite is implied; she is a victim of an abusive system where husbands can freely divorce their wives, leaving a woman used and helpless so that even her most recent “man” will not marry her. Others argue that nothing in the narrative suggests that the woman’s sin is being exposed, only the omniscience of Jesus.28 While it is true that the narrative is not showing a narrow interest in the sin of the woman, the reader of John would be mistaken to claim it is absent. The Fourth Gospel has been quite keen to expose the sin of its characters, and Jesus himself is also shown to be aware of “what was in humanity” (2:25). Furthermore, to focus exclusively on what the narrative is stating about Jesus harmfully minimizes the significance of Jesus’s statement about the woman’s personal life. The omniscience of Jesus is no less an implication from the text than the exposed sinfulness of the woman. Even more, the woman’s pronouncement of Jesus as a prophet (v. 19) suggests not only that Jesus has special insight about her but that the insight is connected to his status as a religious man of God (cf. v. 29). Finally, the OT images projected by the symbolism of the “well of water” (v. 14) are loaded with images of cleansing from sin (cf. Zech 13:1). Rather than being a “secondary interpretation,”29 the sin of the woman is an essential component in the dialogue, serving to describe the tension and separation between the two historical parties (Jews and Samaritans) and the two cosmological parties (God and humanity).

4:19 The woman said to him, “Sir, I see that you are a prophet” (λέγει αὐτῷ ἡ γυνή, Κύριε, θεωρῶ ὅτι προφήτης εἶ σύ). Direct insight into the woman’s life yields fresh insight regarding the person of Jesus. The vocative need not mean more than “Sir” (Κύριε), as it surely meant in vv. 11 and 15, but at this point in the dialogue it might now be bending toward its deeper meaning: “Lord.”30 The Samaritan woman deems Jesus to be “a prophet” (προφήτης), which probably suggests he is a prophetic “seer,” but also that he is competent to speak about spiritual things (cf. 9:17). The Synoptics show that this was the most general verdict pronounced by people when they saw a man of God at work, being applied to both John the Baptist (Matt 14:5; Mark 11:32; Luke 1:76) and Jesus (Matt 21:11, 46; Luke 7:16). Although the noun is anarthrous, the woman was probably only describing Jesus as a prophet in general, not as “the (messianic) prophet” of Deuteronomy 18:15, especially in light of v. 25. The woman has become intrigued by the man of God standing before her.

4:20 “Our fathers worshipped on this mountain, and you claim that the place where it is necessary to worship is in Jerusalem” (οἱ πατέρες ἡμῶν ἐν τῷ ὄρει τούτῳ προσεκύνησαν· καὶ ὑμεῖς λέγετε ὅτι ἐν Ἱεροσολύμοις ἐστὶν ὁ τόπος ὅπου προσκυνεῖν δεῖ).

The Samaritan woman has begun to recognize that Jesus is able to speak to spiritual things. Her dialogue with Jesus has changed from cutting rejoinders to serious interest. She has not, however, come to join his side. She clearly sees a difference between her people, “our fathers” (οἱ πατέρες ἡμῶν) and Jesus’s, designated by the emphatic “you (pl.) claim” (ὑμεῖς λέγετε). If it was difficult for the Samaritan woman to grasp Jesus’s claim about a superior water and well, it would be even more puzzling for her to get around the differences separating Samaritans and Jews, who worship in different places and therefore worship differently. The woman has raised one of the most controversial topics between Jews and Samaritans, with the latter rejecting Jerusalem and building their own temple on Mt. Gerizim, a rival temple.31 How can Jesus raise such spiritual things with her when they do not agree on the starting premises?

The rhetorical dialogue between Jesus and the Samaritan woman seems to adjust at this point. As much as Jesus continues to employ elements of a rhetorical challenge to her, they function less to describe the separation between a Jew and a Samaritan and more to describe the separation between a holy and righteous God and his sinful creation. The remainder of the rhetorical distinctions befitting such a dialogue is now between God and the world—both Jew and gentile—as Jesus announces the mode by which God and humanity must relate. Surprisingly, Jesus has taken a rhetorical challenge, the form of dialogue with the least assumptions of engagement or agreement, and is turning it into an invitation—a witness, all the while maintaining the distinctions that exist between God and the world.

4:21 Jesus said to her, “Believe me, woman, because the hour is coming when you will worship the Father neither on this mountain nor in Jerusalem” (λέγει αὐτῇ ὁ Ἰησοῦς, Πίστευέ μοι, γύναι, ὅτι ἔρχεται ὥρα ὅτε οὔτε ἐν τῷ ὄρει τούτῳ οὔτε ἐν Ἱεροσολύμοις προσκυνήσετε τῷ πατρί). The response Jesus gives to the Samaritan woman’s statement in v. 20 is shocking. Jesus proclaims a worship that is not defined by Samaritans or Jews. By addressing her as “woman” (γύναι), Jesus is not speaking derogatorily to her but, just as he spoke to his mother, is using it respectfully and possibly affectionately even if with a sense of distancing (see comments on 2:4). What he is about to offer her suggests she is the recipient of his affection.

Jesus tells the woman to “believe” (πίστευέ) him, which is without parallel in John and is often taken as an asseverative, an idiom expressing solemnly the truth of what one is about to say (i.e., “I tell you the truth”). But this need not exclude the overtones of the imperative. Similar to when Jesus says “truly, truly,” much more is implied (see comments on 1:51). This is at least an implicit command to believe (similar to the polite command of a superior in 4:7), which at the cosmological level has much more force. The command to believe is hardly language for volunteers. When God speaks with an imperative, a looser sense is grammatically possible but theologically improbable. While she may choose not to believe, such a decision will have consequences. Such consequences give an “unseen” force to the command that the reader is able to feel. Jesus is not just asking for a generic belief but a belief nuanced by the dative pronoun “in me” (μοι). Ironically, she is not merely being exhorted to believe him, that is, believe what he says to her, but to believe “in him” that he is the thing about which he speaks. In light of this, it is not surprising that Jesus again mentions the “hour” (ὥρα), which serves in the Gospel as a technical term to refer to the death of Jesus on the cross (see comments on 2:4).

It is important to note that although Jesus addresses her individually, the people about whom he speaks are plural: “you (all) will worship” (προσκυνήσετε). It is ironic that as the Samaritan stood beside the well—located neither in Jerusalem nor on Mt. Gerizim—she had never been closer to the place where God is worshipped. For she was standing before the true temple of God and the true revelation of the Father (cf. 1:18; 2:21).

4:22 “You worship what you do not know; we worship what we know, for salvation is from the Jews” (ὑμεῖς προσκυνεῖτε ὃ οὐκ οἴδατε· ἡμεῖς προσκυνοῦμεν ὃ οἴδαμεν, ὅτι ἡ σωτηρία ἐκ τῶν Ἰουδαίων ἐστίν). Focusing more directly on the topic of worship, Jesus gives definition to the nature and origin of true worship. The grammar of the verse is significant. The use of plural pronouns by Jesus in v. 21 continues here, with the “you” (ὑμεῖς) and “we” (ἡμεῖς) functioning emphatically, setting Samaritans and Jews in sharp contrast. Of note is that Jesus applies a neuter relative pronoun not only to the Samaritans but also to the Jews and “what” (ὃ) they worship, for even though the Jews “know” (οἴδαμεν) “what” they worship, they do not know “who” he is, for they do not yet have knowledge of the Father through the Son (1:18).

There is one important distinction Jesus makes: “Salvation is from the Jews” (ἡ σωτηρία ἐκ τῶν Ἰουδαίων ἐστίν). The word “salvation” (σωτηρία) occurs nowhere else in John and provides an ironic twist to the scene: salvation is “from” the Jews and yet it has gone “to” no other people. The centuries-old conflict between the Jews and the Samaritans shows the Jews to be acting without any concern for the salvation of the world. They have embraced the “I will bless you” declared to Abraham and have forgotten that in response they were to “be a blessing” to others (Gen 12:2–3). This is why it is significant that salvation is “from” (ἐκ) the Jews and not “in” or “by” them. The rhetorical challenge is providing helpful insights, revealing how Jesus is supporting the distinctions between the two parties and simultaneously breaking the traditional mold by showing that both parties are ultimately inadequate. As much as Jesus must embrace his Jewishness, for salvation is from the Jews, he is also correcting what it means to be Jewish. He is the true Jew, through whom all people on earth will be blessed (Gen 12:3). Jesus is the “blessing” given to the Jews, and it is through the Jewish Jesus that the rest of the world is blessed (see comments on v. 42).

4:23 “But an hour is coming and now is when the true worshippers will worship the Father in Spirit and truth, for this is the kind of worshippers the Father seeks” (ἀλλὰ ἔρχεται ὥρα, καὶ νῦν ἐστιν, ὅτε οἱ ἀληθινοὶ προσκυνηταὶ προσκυνήσουσιν τῷ πατρὶ ἐν πνεύματι καὶ ἀληθείᾳ· καὶ γὰρ ὁ πατὴρ τοιούτους ζητεῖ τοὺς προσκυνοῦντας αὐτόν). By restating the connection of worship to the “hour” (ὥρα), Jesus is making the cross the central component of worship. That the “hour” is simultaneously “coming” (ἔρχεται) and “now is” (νῦν ἐστιν), though an oxymoron, reflects the paradoxical intrusion of the cosmological into the historical first introduced in the prologue. It is not merely a rhetorical device; it is detailing the overlap between God’s time (beyond time) and humanity’s time (linear time). In the same way, the man who is speaking this is not only standing with this Samaritan woman but has always been with God (1:1).

The cross is central to worship because it fosters “true worshippers” (οἱ ἀληθινοὶ προσκυνηταὶ). In the eyes of God, it is neither Jew nor Samaritan (i.e., gentile); the designation of choice is “true worshipper,” which is nothing less than a new race. True worshippers must be “children of God” (1:12), and when God’s children speak of “Father” they do not think of their natural ancestry but of their cosmological ancestry rooted in their heavenly Father. Everything other than this “true worship” was either proleptic or pagan.32 True worshippers “will worship the Father” (προσκυνήσουσιν τῷ πατρὶ). McHugh creatively describes the dative here as a “liturgical dative.”33 Those the Father loved (3:16) will respond by worshipping him. And just as Jesus mediated the love of the Father to the world, so also does Jesus mediate true worship to the Father. This presents a stark contrast with the neuter “what” (ὃ) worshipped by both Samaritans and Jews in v. 22. It is not a “what,” not even “God,” but the Father who is to be worshipped. Worship is only “true” when it is correctly directed at the Father. And the more the Father is made central, the more Jesus becomes central. Such are the unifying distinctions of the Trinitarian God.

It is not merely worship that makes central the Father by the Son, for such worship must be done “in Spirit and truth” (ἐν πνεύματι καὶ ἀληθείᾳ). This phrase has been given a lot of attention. The preposition “in” (ἐν) governs both nouns; they are not two separate characteristics of appropriate worship. The conjunction “and” (καὶ) is not functioning epexegetically (i.e., “that is”) but is simply a connective conjunction. Thus, the two nouns must be taken together to make sense of the phrase.

Several interpreters argue that “Spirit” (πνεύματι) refers to the spirit of a person (i.e., the human spirit), so that the contrast is between the right place of worship and the right attitude, “in their inner self, with their mind, their feelings, and their will engaged in activity.”34 But the Spirit, drenching the pages of the Fourth Gospel and already made central to the renewal about which Jesus speaks, is the Spirit of God. The Spirit will shortly be described as the “Spirit of truth” (14:17; 15:26; 16:13). Even more, “it would be foolish to ask what the Spirit contributes to worship as distinct from what truth contributes.”35 Spirit and truth describe the manner in which one receives the “gift of God” and drinks the “living water” Jesus provides (v. 10). The Christian life, therefore, is Trinitarian by nature: “True worship is paternal in focus (the Father), personal in origin (the Son), and pneumatic in character (the Spirit).”36

After all this focus on the manner in which the Christian accesses God, v. 23 ends with the shocking declaration that it is actually the Father who “seeks” (ζητεῖ) such worshippers. The verb carries more the sense of “demands” or “asks for,” though the idea of “seeking” or “searching” is to be maintained as well and is used in this primary sense elsewhere in John (cf. 18:4).37 This statement echoes the purpose of the Gospel (20:30–31).38

4:24 “God is Spirit, and his worshippers must worship in Spirit and truth” (πνεῦμα ὁ θεός, καὶ τοὺς προσκυνοῦντας αὐτὸν ἐν πνεύματι καὶ ἀληθείᾳ δεῖ προσκυνεῖν). Worship is done in “Spirit and truth” because God’s essential nature is Spirit. This not only explains the manner in which God must be worshipped but also explains the contrast with place. True worship must be spiritual in nature; the only temple allowed is the body of Jesus. In a real way, everything that God does is befitting his nature. In view of what has already been described as coming from God, the declaration that God is Spirit alludes to the life-giving activity of God. This necessarily restricts worship to the nature and character of God, yet it also expands worship, for it posits God as the true source and “fountain” of such worship (cf. v. 14). For this reason, this kind of worship is not an option but a necessity, denoted by “must” (δεῖ). In vv. 21–24, the verb “worship” (προσκυνεῖν) is spoken seven times by Jesus—a significant number.

4:25 The woman said to him, “I know that Messiah is coming (called Christ). When he comes, he will proclaim everything to us” (λέγει αὐτῷ ἡ γυνή, Οἶδα ὅτι Μεσσίας ἔρχεται, ὁ λεγόμενος Χριστός· ὅταν ἔλθῃ ἐκεῖνος, ἀναγγελεῖ ἡμῖν ἅπαντα). From the Samaritan woman’s perspective, Jesus is speaking with messianic allusions and connotations. It has frequently been suggested that the woman’s use of the term “Messiah” (Μεσσίας) is a reference to the Taheb, the restorer of Deuteronomy 18:18, the Samaritan equivalent to the Jewish messiah. But there is no clear evidence for this reconstruction. The narrator’s explanatory addition of “called Christ” (ὁ λεγόμενος Χριστός) reflects the varied terms used for this identity; the variations in definition were even more extensive. At most we can be certain that both Jews and Samaritans had messianic conceptions, with several important differences between them.39 Jesus’s statements about a coming “hour” and his matching the expectation of a teacher may have guided her insight. She likely had no concern beyond this vague information because this messiah would “proclaim” (ἀναγγελεῖ) everything, that is, “explain” what is to come. The scene is drenched with irony: a Samaritan woman is explaining messianic expectations to the Messiah.

4:26 Jesus said to her, “I am (he), the one speaking to you” (λέγει αὐτῇ ὁ Ἰησοῦς, Ἐγώ εἰμι, ὁ λαλῶν σοι). Jesus’s statement is emphatic and strongly impressionistic. With the careful choice of words, “I am he” (Ἐγώ εἰμι), which adds an emphatic “I” and has no “he” in the Greek (“I, I am”), Jesus speaks in the style of the God of the OT (on informal “I am” statements, see comments on 8:58).40 The self-revelation God gave to Moses through a bush in Exodus 3 has now been spoken to a Samaritan woman through the incarnate God. Jesus’s response is both a correction and a revelation. So much of what the Samaritan woman believed was wrong or incomplete. She had been waiting for a “what” (v. 22), yet all the while the “who” was standing before her. His revelation is his correction, for there is no need to adjust her messianic theology. He only needs to announce his presence. The irony of v. 25 has been traded for a new irony: the Jewish Messiah announces his presence in Samaria to a Samaritan woman in the middle of a rhetorical challenge. It is equivalent to the birth of the King of kings in a stable! This verse ends the rhetorical challenge proper. The rest of the pericope draws the encounter to a close by providing the necessary resolution and interpretation to the scene.

4:27 Just then his disciples came and were surprised that he was speaking with a woman. But no one said, “What do you seek?” or “Why are you speaking with her?” (Καὶ ἐπὶ τούτῳ ἦλθαν οἱ μαθηταὶ αὐτοῦ, καὶ ἐθαύμαζον ὅτι μετὰ γυναικὸς ἐλάλει· οὐδεὶς μέντοι εἶπεν, Τί ζητεῖς; ἤ, Τί λαλεῖς μετ’ αὐτῆς;). The dialogue scene changes upon the return of the disciples from their trip to purchase food (cf. v. 8). The narrator describes them arriving “just then” (ἐπὶ τούτῳ), a phrase which functions temporally to explain that they arrived immediately following the concluding revelation of Jesus.41 The disciples “were surprised” (ἐθαύμαζον), with the imperfect tense suggesting that their surprise was more than momentary. They were shocked to see him “speaking with a woman” (μετὰ γυναικὸς ἐλάλει). It is often suggested that it was considered undesirable for a rabbi to speak with a woman (m. ’Abot 1:5), and certainly the fact that she was a Samaritan only caused more surprise.

The narrator informs us of the two unspoken questions that surfaced from their surprise. To the woman they wanted to ask: “What do you seek?” (Τί ζητεῖς;); to their teacher they wanted to ask: “Why are you speaking with her?” (Τί λαλεῖς μετ’ αὐτῆς;). Even though the disciples are unaware of the issues raised by the dialogue, their questions serve to make more resolute the dialogue’s message. The verb “seek” (ζητεῖς) is significant, for it was the same verb used to describe the action of God in v. 23. The reader has been guided to see that while the woman did not know what she was seeking, God was seeking her.

4:28 Then the woman left her water jar and went into the city and said to the people (ἀφῆκεν οὖν τὴν ὑδρίαν αὐτῆς ἡ γυνὴ καὶ ἀπῆλθεν εἰς τὴν πόλιν καὶ λέγει τοῖς ἀνθρώποις). The narrator returns to the Samaritan woman and her response to the correction and revelation of Jesus. She is described as leaving her water jar and returning to her city to share her news with the people. The imagery is potent. The narrative’s focus on the abandoned water jar reflects the abandonment of Samaritan water for a wholly different kind of water (v. 14). For just feet away from Jacob’s well, she had been introduced to a wholly other drinking source. It is also important to note that the narrator includes the disciples of Jesus in the aftereffects of the dialogue (v. 27) before giving the final response of the Samaritan woman (v. 28). The narrator probably intends to make clear that all people, not just the Samaritans, are in need of what the Samaritan woman had just received.

4:29 “Come, see a man who told me everything that I did. This is not the Christ, is it?” (Δεῦτε ἴδετε ἄνθρωπον ὃς εἶπέν μοι πάντα ὅσα ἐποίησα· μήτι οὗτός ἐστιν ὁ Χριστός;). The Samaritan woman does not merely show the effect Jesus had on her; she also proclaims it. In a sense, she has become like the earliest followers of Jesus, using nearly identical language: “Come, see” (cf. 1:39, 46). The woman invites them to meet “a man” (ἄνθρωπον) who “told me everything that I did” (εἶπέν μοι πάντα ὅσα ἐποίησα). This “pardonable exaggeration” describes how deep and personal was her encounter with Jesus.42 She speaks not as a theologian—she never really did have good theology; rather, she speaks as a witness to someone whom she did not understand but who had understood her. It is important to note that the Samaritan woman concludes with a question that, with this particular negative particle “not” (μήτι), expects a negative answer or at least communicates serious hesitation.43 The effect is not necessarily to challenge the possibility that he is the Messiah but to introduce a possibility not considered before.44 In a way, the Samaritan woman left the rhetorical challenge with Jesus and entered an entirely different rhetorical challenge, one involving the possibility of a Jewish Messiah for the Samaritans. Having watched Jesus broach a sensitive topic, the Samaritan woman carefully poses an exhortative rhetorical question to her own people.45 This was no ploy, however, but the question everyone needed to answer for themselves.

4:30 They came out of the town and came toward him (ἐξῆλθον ἐκ τῆς πόλεως καὶ ἤρχοντο πρὸς αὐτόν). The effect of the Samaritan woman’s witness was positive. In just two verses, she enters the town, and the townspeople come out of it. The Samaritan woman had become a witness and proves that it is not the quality of the witness that ultimately matters but the object of the witness.

4:31 In the meantime his disciples urged him saying, “Rabbi, eat” (Ἐν τῷ μεταξὺ ἠρώτων αὐτὸν οἱ μαθηταὶ λέγοντες, Ῥαββί, φάγε). The scene changes from the effects of Jesus on the Samaritan woman and her village to the disciples, who in their faithful search for food have missed the provision Jesus already provided. The uncommon phrase “in the meantime” (ἐν τῷ μεταξὺ) makes explicit the direct overlap between the two scenes the narrative is moving between. The scene involving vv. 27–38 serves as an interlude that propels forward the central theme of the dialogue. The contrast is filled with irony and bears witness to the inability of all (Samaritans and Jews alike) to view Jesus and his provision through their own lenses (cf. 1:5). The Samaritan woman saw a “prophet”; the disciples saw a “rabbi” (Ῥαββί).

4:32 But he said to them, “I have food to eat that you know nothing about” (ὁ δὲ εἶπεν αὐτοῖς, Ἐγὼ βρῶσιν ἔχω φαγεῖν ἣν ὑμεῖς οὐκ οἴδατε). The ignorance exhibited by the disciples in v. 31 is now directly addressed by Jesus. They both speak of food but mean something very different. The whole expression “I have food to eat” (Ἐγὼ βρῶσιν ἔχω φαγεῖν) is a metaphor that depicts the sustenance and nourishment he owns and provides in his very person as the source of “living water” and as “the bread of life” (6:35). Without ever denying that even the Word-become-flesh needs food, Jesus shows the symptoms of one who finds their sustenance in God.

4:33 Then the disciples were saying to one another, “Could someone have brought him something to eat?” (ἔλεγον οὖν οἱ μαθηταὶ πρὸς ἀλλήλους, Μή τις ἤνεγκεν αὐτῷ φαγεῖν;). The disciples are completely confused. They have missed the dialogue with the Samaritan woman and have been “in the meantime” in search of food (v. 31). When Jesus speaks of having food already he confuses his disciples, and rightly so. We do not want to be too dismissive of the disciples at this point. The Samaritan woman showed the same confusion. In the context of a well, Jesus spoke about water; in the context of a search for food, Jesus speaks about already having food. Jesus uses real food to speak about something more real, for he is speaking in “parabolic language” in order to move the minds of his disciples beyond themselves (and their stomachs) to the unseen.46

4:34 Jesus said to them, “My food is to do the will of the one who sent me and to finish his work” (λέγει αὐτοῖς ὁ Ἰησοῦς, Ἐμὸν βρῶμά ἐστιν ἵνα ποιήσω τὸ θέλημα τοῦ πέμψαντός με καὶ τελειώσω αὐτοῦ τὸ ἔργον). If the disciples had misunderstood Jesus before, this statement only made things more complicated. Jesus is not merely thinking about some sort of spiritual food—water from rocks and manna—but about something much greater, much more cosmic. Even the different term used here for “food” (βρῶμά), in comparison with “food” (βρῶσιν) in v. 32, is often used to denote a special connotation of nourishment, something more than the mere physical substance, though the differences are best nuanced by the larger context.47 This verse only makes sense when we remember that the prologue taught the reader to see the unseen and to look beyond the historical to the cosmological. Without denying the necessity of food, Jesus is using properly basic nourishment to convey something even more basic and nourishing.

It is important to note that Jesus aligns his needs with “the one who sent me” (τοῦ πέμψαντός με). Jesus is so exclusively defined by the Father and his “sending” that even food is made subsidiary. That is why Jesus claims to do another’s “will” (θέλημα) and “work” (ἔργον), terms used exclusively in the Fourth Gospel for the Father’s work of salvation. It is never the work of Jesus or his disciples; it is always the work of the Father (cf. 17:4). Jesus is so dependent on the Father that the Father’s will and work is food to him, and he is actually hungry for it, actually craving its accomplishment (cf. Deut 8:3). Jesus’s “life” was sustained ultimately by God.

4:35 “Do you not say that there are still four months and then the harvest comes? Behold, I say to you, lift up your eyes and look at the fields that are already white for the harvest” (οὐχ ὑμεῖς λέγετε ὅτι Ἔτι τετράμηνός ἐστιν καὶ ὁ θερισμὸς ἔρχεται; ἰδοὺ λέγω ὑμῖν, ἐπάρατε τοὺς ὀφθαλμοὺς ὑμῶν καὶ θεάσασθε τὰς χώρας ὅτι λευκαί εἰσιν πρὸς θερισμόν ἤδη). Jesus turns from his unique food (as the unique Son) and speaks now to the rest of the Father’s children about their food: the will and work of God. By describing the fields as “white” (λευκαί) for the harvest, Jesus is describing them as ready to be harvested. There should be no delay. The two-imperative phrase, “Lift up your eyes and look” (ἐπάρατε τοὺς ὀφθαλμοὺς ὑμῶν καὶ θεάσασθε), and a third if we include “behold” (ἰδοὺ), are exhorting a certain kind of vision, the same kind that is hungry, but not for bread alone, or thirsty, but unsatisfied without “living water.” Jesus is now speaking directly about what the prologue depicted as the “unseen.” What they cannot see is that Jesus can already now “see” a horde of Samaritans coming down the road toward him.48 They are Samaritans satisfied from their recent meal at midday (cf. v. 6), yet still hungry. It is another exhortation to “come and see” (cf. 1:46). They have come but have not yet seen.

4:36 “The harvester is receiving payment and gathering crop for eternal life, so that the sower might rejoice together with the harvester” (ὁ θερίζων μισθὸν λαμβάνει καὶ συνάγει καρπὸν εἰς ζωὴν αἰώνιον, ἵνα ὁ σπείρων ὁμοῦ χαίρῃ καὶ ὁ θερίζων). This type of sowing and harvesting is unique not only in the lack of delay but also in regard to unity: the sower does not get replaced by the harvester but cooperates in unity (cf. Deut 28:33; Judg 6:3; Mic 6:15). Interpreters debate the identity of the “sower” and the “harvester,” but Jesus is not only silent on the issue but locates them in such a unified fashion that the differences coalesce into one grand “work.”49 This grand work was promised through the prophet Amos: “The days are coming . . . when the reaper will be overtaken by the plowman and the planter by the one treading grapes” (9:13). This reality, depicted by a crop so rich that the work of the sower and harvester overlaps, is portrayed by John as the “already” present eschatological harvest. The result of this harvest—the food it produces—is “for eternal life” (εἰς ζωὴν αἰώνιον). What is harvested are people (e.g., Samaritans) for whom eternal life is given. God hungers and thirsts for the world he loves (3:16).

4:37 “For in this the saying is true that one is the sower and the other is the harvester” (ἐν γὰρ τούτῳ ὁ λόγος ἐστὶν ἀληθινὸς ὅτι Ἄλλος ἐστὶν ὁ σπείρων καὶ ἄλλος ὁ θερίζων). Jesus now applies his statements above more directly to the disciples, again with what appears like another proverbial statement. Although the eschatological harvest is at hand and has unified the crop from beginning to end, it should not remove all distinctions so that those who harvest have forgotten their role and their purpose. Even if they are after the same result, sowing and harvesting are different tasks.

4:38 “I sent you to harvest that for which you have not labored. Others have labored, and you have entered into their labor” (ἐγὼ ἀπέστειλα ὑμᾶς θερίζειν ὃ οὐχ ὑμεῖς κεκοπιάκατε· ἄλλοι κεκοπιάκασιν, καὶ ὑμεῖς εἰς τὸν κόπον αὐτῶν εἰσεληλύθατε). With v. 37 in mind, Jesus presses upon his disciples their unique entrance into this grand “work.” With emphasis Jesus declares, “I sent you” (ἐγὼ ἀπέστειλα ὑμᾶς), placing the disciples into their position by means of the “will” and purpose of God. It is a position that is simultaneously honorific and humbling in the magnitude of “labor” that has been done by “others.” As much as the referent of “others [who] have labored” is cryptic and tempting, the point is not to survey salvation history in all its specifics but to press upon the disciples their role and identity. Whatever the specifics, the disciples “have entered into” (εἰσεληλύθατε) their labor, a verb which allows for their distinctive role all the while portraying their work as part of the unified eschatological work of God.50

Jesus is not intentionally speaking past his disciples, even if we note misunderstanding and irony in the foreground and allusions to larger theological themes in the background. He is revealing the Father (1:18), especially his “will” and “work.” He is also revealing the gospel and is including them as recipients of its nourishing food and its joyous harvest. While the disciples were plodding through a Samaritan village looking for food to feed their “rabbi,” he was already offering food from the eschatological harvest of God to a Samaritan woman. The disciples had gone to a Samaritan village to buy food, when instead they should have gone there to provide it—not their own provision, of course, but the harvesting of what had already been sown. The narrator has carefully crafted this teaching in the center of the actual “harvesting” of the Samaritan woman by Jesus, allowing the disciples—and the reader—to “see” what a harvest looks like (v. 35).

4:39 And from that city many of the Samaritans believed in him because of the word of the woman who testified, “He told me everything that I did” (Ἐκ δὲ τῆς πόλεως ἐκείνης πολλοὶ ἐπίστευσαν εἰς αὐτὸν τῶν Σαμαριτῶν διὰ τὸν λόγον τῆς γυναικὸς μαρτυρούσης ὅτι Εἶπέν μοι πάντα ὅσα ἐποίησα). The narrative’s return to the Samaritans directly after the didactic interlude between Jesus and his disciples not only brings the Samaritan woman pericope to a dramatic close but also serves to explain in material terms what the interlude had spoken of in abstraction. With the verb “believed” (ἐπίστευσαν) and the preposition “in” (εἰς), the idea communicated is that they “put their faith in” him. The preposition “because of” (διὰ) is functioning causally so that the “word” of the woman facilitated their belief. Ultimately, however, the “word” of the Samaritan woman is subservient to the “word” of Jesus (see v. 41). Although “the word” (τὸν λόγον) could be translated more softly as “the message,” it is hard not to see the use of this particular term in light of the prologue, making emphatic that the message of the woman was entirely centered on the definitive Word—Jesus Christ. The message of the woman is identical to what she was recorded as saying earlier (see comments on v. 29). What is important is that the narrative prefaces her statement with the important term “testified” (μαρτυρούσης). This is an important term in the Fourth Gospel (see comments on 1:7) and serves to portray the task of the Christian disciple.

4:40 When the Samaritans came to him, they were asking him to remain with them, and he remained there two days (ὡς οὖν ἦλθον πρὸς αὐτὸν οἱ Σαμαρῖται, ἠρώτων αὐτὸν μεῖναι παρ’ αὐτοῖς· καὶ ἔμεινεν ἐκεῖ δύο ἡμέρας). The witness of the Samaritan woman turned into a host of Samaritan “followers.” The estrangement between Jew and Samaritan has entirely dissolved into the request of students to a teacher; their actions suggest they were coming to become his disciples, which is why they want him to remain with them (cf. 1:37–39). The rhetorical challenge has been reversed. Rather than a long-established opposition in which conflict is merely to reestablish socially antithetical positions, the reverse has taken place. The two sides have centered upon Jesus, in whom they find a unity.

While the actions of the Samaritans showed true hospitality, the actions of Jesus reflected those of a true prophet (cf. the expectations between a host and a visiting prophet in Did. 11:4–5; cf. John 12:2). Jesus was a prophet in word and deed (cf. v. 19). In the gracious providence of God, Jesus displayed for the Samaritans the prophet God had promised them. The hospitality of the Samaritans to Jesus is simply (if unknowingly) a response to the gracious hospitality of the Word-become-flesh who “came to what belongs to him” (1:11).

4:41 And many more believed because of his word (καὶ πολλῷ πλείους ἐπίστευσαν διὰ τὸν λόγον αὐτοῦ). The narrative explains that at the gathering between Jesus and the Samaritans who came to him, “many more” (πολλῷ πλείους) put their faith in him. In a similar manner to the woman, the many believed “because of his word” (διὰ τὸν λόγον αὐτοῦ). While the message—the “word”—was the same in that it was centered upon Jesus, from Jesus it was a first-person message, an autobiographical statement. The witness of the Samaritan woman was always secondary to the witness of the Word himself, who is the first-order witness to the Father (1:18).

4:42 And they were saying to the woman, “We no longer believe because of your message, for we have heard and we know that this man is truly the Savior of the world” (τῇ τε γυναικὶ ἔλεγον ὅτι Οὐκέτι διὰ τὴν σὴν λαλιὰν πιστεύομεν· αὐτοὶ γὰρ ἀκηκόαμεν, καὶ οἴδαμεν ὅτι οὗτός ἐστιν ἀληθῶς ὁ σωτὴρ τοῦ κόσμου). Even the Samaritans detect the mediated nature of the woman’s “message” (λαλιὰν) and acknowledge that her word has been eclipsed by the true Word. The term “message” (λαλιὰν) is distinct from “word” (λόγος) and means something much less sublime—characteristic “talk” in general or even “chatter” in classical Greek.51 Such a statement, then, not only reveals the first-order status of Jesus’s message—she spoke, but he proclaimed the word—but also the success of the woman’s message. A successful witness works so that they become entirely secondary, even unnecessary, in the presence of God, the object of their witness. This is not, however, to eliminate the necessity of the second-order witness. Indeed, the woman’s word brought the Samaritans to the word of Jesus, so that faith is ultimately “because of his word” (v. 41).52 This is what the Samaritans confess. They declare with two perfect tense verbs to “have heard” (ἀκηκόαμεν) and “know” (οἴδαμεν) who Jesus is. A mediatory witness at this point would be both unnecessary and cumbersome. With a term that echoes the confidence of the prologue, the Samaritans declare that “this [man]” (οὗτός) is the Savior (cf. 1:2).

The witness of the Samaritan woman and self-attesting witness of Jesus is that he is “the Savior of the world” (ὁ σωτὴρ τοῦ κόσμου). The qualification that he “truly is” (ἐστιν ἀληθῶς) not only confirms the reliability of the object of their faith but also serves as the beginning of their own confession, their own witness. The phrase “Savior of the world” has been analyzed by interpreters from the perspective of the Samaritans—what they believed based upon their context and theology.53 Like the declaration of John the Baptist regarding the “Lamb of God” (see comments on 1:29), the title means much more than the Samaritans could have imagined. The term cannot be defined by the Taheb (cf. v. 25) and the context of the Samaritans but must be defined by Jesus and the context of his mission from the Father. If anything, this pericope has declared that Jesus is more than the Taheb. Yet something quite shocking has also been revealed, especially as it relates to the Jews. In a very real sense, Jesus is even more than the Jewish Messiah. Even in the OT, where God is sometimes described as “Savior,” it is usually applied to his saving work for his own people. The grand scope of the mission of God and of his harvest demands that Jesus be known with the comprehensive title, “Savior of the world.” And thus the pericope ends, with the Jewish Messiah receiving hospitality from a host of Samaritans who sit at his feet in the region of Samaria.54

Theology in Application

If Jesus sparked controversy among the Jews, one could only have imagined the reaction to him by the Samaritans. But what required the most imagination had little to do with the Samaritans and everything to do with God. The seeking God, the Savior of the world, was pursuing true worshippers, for he is worthy of true worship and he had enacted a plan for true worship through his Son. Jesus’s tension-filled dialogue with the Samaritan woman showed that the conflict between the Jews and Samaritans was only symptomatic of the deeper conflict between God and the world he had made. Yet in the providence of God, the “whole grace of renewal”55 had arrived in the person and work of Jesus, because of whom all hunger may be satiated and all thirst quenched. For this reason, the reader of the Fourth Gospel is exhorted not only to eat and drink but also alongside Jesus to announce to the world the meal he alone can offer and the God who alone can provide it. It is harvest time!

“If You Knew the Gift of God . . .”

In his dialogue with the Samaritan woman, Jesus quickly made clear that she did not “know” what she thought she knew. Alongside her were the disciples, Jesus’s intimate followers, who were equally naive to who Jesus was and to what he was doing. Jesus transcended the context and “messianic” theology of the Samaritans and demanded they “come and see” the true God. Jesus also transcended the Jewish context and messianic theology of his disciples and demanded they “look” at the harvest fields. Like the Samaritan woman, the reader is being exhorted to hear the voice of the Word and consider the nature of his or her “messianic” assumptions. Am I worshipping a “what” or a “who” (v. 22), a god of my own making or “the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac and the God of Jacob,” that is, Jesus Christ (Exod 3:6)? And like the disciples, the reader is exhorted to hear the call to embrace the mission of God, to see the ripe fields and to participate in the harvest of God. The Christian is aware that what they once thought about God and about themselves was biased, self-benefitting, and wrong and is reminded to make God and his written Word the rule and guide for self-reflection and the call to duty (mission).

The Hospitable God

The Samaritan woman showed a surprising sensitivity to the enemy of her people and her gender. Although not without cutting rejoinders, through her reactions of surprise at his less-than-attacking conversation with her, the narrative portrayed her as one more trained to receive rebuke than to give it. In the region surrounding this well, Jesus was the guest and she was the host. Yet from the start, he was serving as the host and she the guest. Even at the end of the pericope, when Jesus remained with his new Samaritan followers, although he stayed in their homes and ate their food, it was he who was giving them the truly satisfying meal to eat and water to drink. He had replaced their local well with the well of eternal life.

The Christian, then, no matter the region in which he lives, is living under the hospitality of the God of Jacob’s well. Such a picture makes the local expression of the body of Christ, the local church, a true home, an embassy in a foreign or familiar land. Patriotic songs are sung not to honor the fathers of our land but “our Father.” And differences of skin color, accents, ethnicities, economic and social classes, education, and gender are not erased but embraced under the umbrella of the hospitable God. Moreover, the Christian extends the hospitality of God to the world around them, drinking water with foreigners from local taps that cannot ultimately satisfy and showing those people the true water of the hospitable God.

Whom the Father Seeks

The Samaritan woman was introduced to the God who “seeks,” a term that describes the two sides of God. He is a God that demands a certain kind of worshipper and a certain kind of worship and will not stand for anything below his standard. He is God, we are not; this must be the foundation of our relationship with God. He can and must be sought as he is, not as we want him to be. He must be “sought” as the Father, through Jesus Christ, and in the power of the Holy Spirit. Yet in his mercy and love, he does not just allow himself to be sought; God seeks us. He sent his Son to find us—to drink our water and to eat our food—so that he can be found by us and give to us his water and his food. The Christian knows that it is not only true that “we love because he first loved us” (1 John 4:19); it is also true that we sought him because he first sought us.

The “Jewish Messiah” is the Savior of the World

When the Samaritans heard “Jewish Messiah,” they became defensive, thinking only of themselves. When the Jews heard “Jewish Messiah,” they became offensive, thinking only of themselves. According to this pericope, when God speaks about the “Jewish Messiah,” he is thinking about the whole world. The term is a rebuke not only to those who are not Jewish but also to those who are. It is a term that announces that God loves the whole world, and has sent his son to save it. “Jewish Messiah” is in many ways a summarizing title of the entire Gospel, designating from where the world’s rescuer would arise (Israel) and his mission (he would save the world from their sins). The church, even the most gentile local expression, worships the Jewish Messiah—not because they are or must become Jewish but because they are part of the world over which the Jewish Messiah is declared “Savior.”

True Worship

Christian worship is done in no other temple than the temple of the body of Jesus Christ. It is done through the crucified and resurrected body of Jesus Christ. A church’s worship hour is eternally connected to the “hour” of Christ. True worship is Christ centered and cross centered, since the cross creates the appropriate worshippers—a new race of worshippers that are neither Jew nor Samaritan. True worship is ultimately Trinitarian in that it is directed to the Father, mediated through the Son, and empowered and directed by the Holy Spirit. It is the true worship of a “whom” (not a “what”), through a “whom,” and by a “whom.” This is worship “in Spirit and truth”: paternal in focus (Father), personal in origin (Son), and pneumatic in character (Spirit).56

Such worship, however, is not merely spiritual and therefore disembodied. In sharp contrast, worship done through the body of Christ is only rightly done in the body of Christ, a fitting expression of the local church. The local church does not replace a mountain or a city but is the place of a living expression of worship “in Spirit and truth.” It is the real body of Christ, the place of the real presence of the Holy Spirit, and the real worshippers the Father seeks. Jesus is not calling us to worship in abstraction, but to worship in “Spirit” and in “truth” in the local church.57

The Mission of the Church

The church, like the Jewish disciples of Jesus, can too easily concoct an “ecclesial Messiah” and forget that he came for the entire world! To the church our Lord proclaims, “Behold, I say to you, lift up your eyes and look at the fields that are already white for the harvest” (v. 35). We are too easily concerned with feeding ourselves and forget the harvest that is ripe for picking. At the same time that Jesus exhorts them to work the harvest, however, he reminds them that they are not the only or even primary harvesters. Like a farmer at the time of harvest who feels excitement for the task and a humility in regard to the result, so also a Christian ought to be bent toward serving in the mission of God but simultaneously humbled by the opportunity and by the results of the labor which are in no way their own.

O church, lift up your eyes and look at the fields! Hear the call of God and bring true water to the thirsty and true food to the hungry—bring Jesus to the world. May we embrace the mission of our seeking God and seek the lost, not only around the globe but even around the corner. Lord, let us be conduits of your hospitality for the world, a hospitality that offers no greater security, peace, and comfort than Jesus Christ, your Son.