Chapter 10

John 5:1–18

Literary Context

This pericope begins a new section in the Gospel. Jesus’s public ministry is well underway and as he increasingly becomes the center of attention he is required to explain—to confess—his identity and intentions. Up until now Jesus has been working primarily with individuals, but in this section of the Gospel his ministry begins to engage with more corporate entities, both followers and dissenters. This healing is the third sign of Jesus (cf. 6:2; 7:31).

- IV. The Confession of the Son of God (5:1–8:11)

- A. The Third Sign: The Healing of the Lame Man on the Sabbath (5:1–18)

- B. The Identity of (the Son of) God: Jesus Responds to the Opposition (5:19–47)

- C. The Fourth Sign: The Feeding of a Large Crowd (6:1–15)

- D. The “I AM” Walks across the Sea (6:16–21)

- E. The Bread of Life (6:22–71)

- F. Private Display of Suspicion (7:1–13)

- G. Public Display of Rejection (7:14–52)

- H. The Trial of Jesus regarding a Woman Accused of Adultery (7:53–8:11)

Main Idea

In a world filled with confusion about God and religious superstition, Jesus stands as the direct reflection and primary agent of the personal and powerful work of God. Jesus is both the promise of true wellness and the warning against something much worse. The only appropriate response can be to stop sinning and to start believing.

Translation

Structure and Literary Form

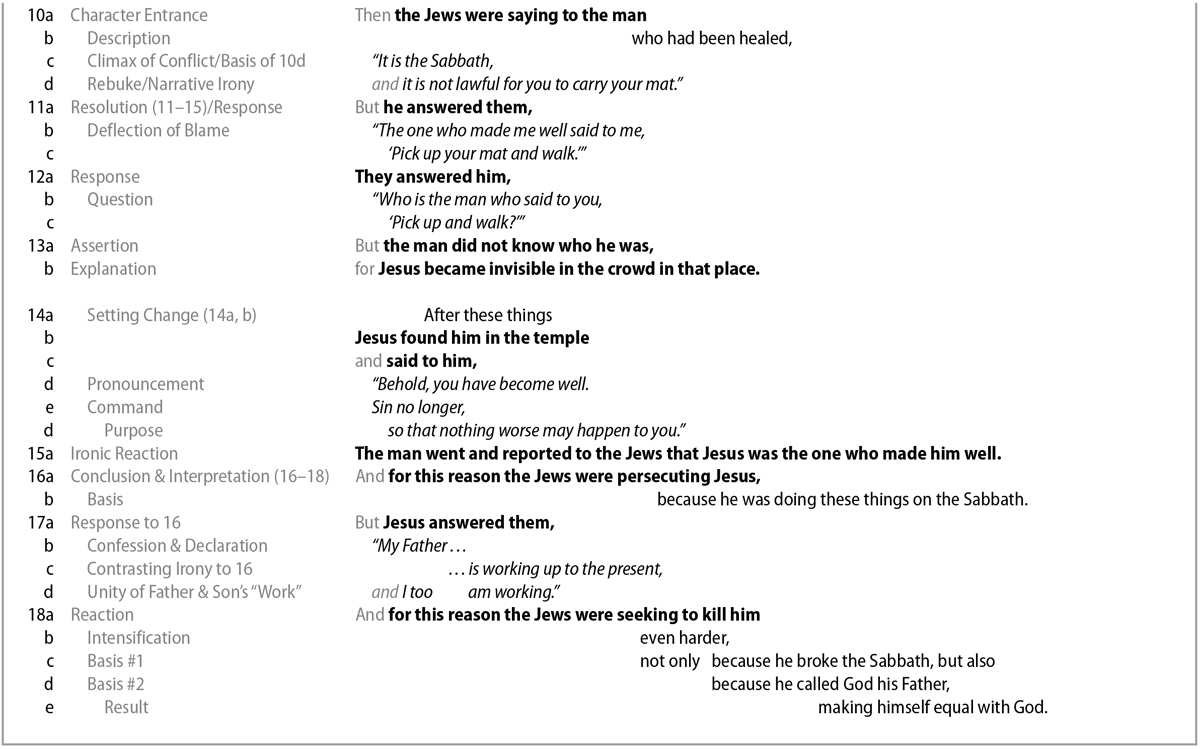

This pericope corresponds to the basic story form (see Introduction). The introduction/setting is established in vv. 1–5, explaining the location, setting, and people around whom the plot’s conflict will focus. The conflict in this pericope in vv. 6–10 is more multifaceted than the previous story units, for it not only involves the healing of the lame man but also the controversy of healing on the Sabbath. It is probably best to view the healing of the lame man as the rising conflict, with the climax of the conflict centering upon the Sabbath controversy. The resolution in vv. 11–15 removes the healed man from the tension and places the conflict directly at the feet of Jesus. Finally, vv. 16–18 serve as the conclusion/interpretation by ending the pericope with a description of the Jews’ intentions regarding Jesus. It also closes the pericope with a confession that sets a trajectory for Jesus’s later public engagement and connects the pericope to the larger witness of the narrative.

Exegetical Outline

- A. The Third Sign: The Healing of the Lame Man on the Sabbath (5:1–18)

- 1. A Man Lame for Thirty-Eight Years (vv. 1–5)

- 2. Get Up—Even on the Sabbath! (vv. 6–10)

- 3. Sin No Longer (vv. 11–15)

- 4. The Work of God, Father and Son (vv. 16–18)

Explanation of the Text

Bultmann states plainly the problem raised by several interpreters: “The present order of chs. 5 and 6 cannot be the original one.”1 Not only does Bultmann note the problem, he even corrects the arrangement of John’s narrative in his commentary, arguing that the original order must have been chapters 4, 6, 5, 7. But there are two reasons why we should be comfortable with the order as we have it. First, there is absolutely no textual evidence that argues against the narrative order as we have it. Second, in order to correct what is seen as a problem at the level of historical sequencing, a new problem is created at the level of the literary sequencing.2 Not only was historical narration allowed a level of freedom and flexibility in the ancient world, a freedom in the amount and ordering of its contents (cf. 20:30: “Many other miracles . . . not recorded in this book”), but narration was also written with a particular literary sequencing in mind, a sequencing that was intended to communicate to the reader by means of its specific order. The received order makes good narrative sense, as we shall see below.

5:1 After these things there was a festival of the Jews, and Jesus went up to Jerusalem (Μετὰ ταῦτα ἦν ἑορτὴ τῶν Ἰουδαίων, καὶ ἀνέβη Ἰησοῦς εἰς Ἱεροσόλυμα). “After these things” (Μετὰ ταῦτα) loosely connects this pericope to the previous one and functionally may mean little more than, “The next thing I would like to tell is this” (see comments on 2:12).3 The narrator explains that Jesus returned to Jerusalem for “a festival of the Jews” (ἑορτὴ τῶν Ἰουδαίων). No indication is given as to which festival is taking place; the anarthrous “a festival” almost emphasizes the anonymity. This is the only occurrence of an unnamed festival in the Gospel, which normally names the festival in question: 2:23; 6:4; 11:55–56 (Passover); 7:2 (Tabernacles); and 10:22 (Dedication/Hanukkah). Since festivals in John are often linked thematically to the events at hand, the lack of reference in this pericope suggests there is no innate or necessary connection.

5:2 And there is in Jerusalem near the Sheep Gate a pool, which in Aramaic is called Bethesda, which has five porticoes (ἔστιν δὲ ἐν τοῖς Ἱεροσολύμοις ἐπὶ τῇ προβατικῇ κολυμβήθρα ἡ ἐπιλεγομένη Ἑβραϊστὶ Βηθζαθά, πέντε στοὰς ἔχουσα). The specific scene of this pericope takes place at a pool near the Sheep Gate. The specifics provided reflect the awareness John had of Jerusalem and its geography.4 Some have argued that the present-tense verb “is” (ἔστιν) implies that the Gospel was written before Jerusalem was destroyed, hence before AD 70, but this is not demanded from the verb.5 Rather than intending directly to communicate a historical fact, the employment of this common verb is best understood to be inviting the reader “to visualize the scene as it unfolds.”6

While the exact site is difficult to confirm, several scholars suggest the twin pools beneath St. Anne’s Monastery.7 The pools were as large as a football field and about twenty feet deep. The “five porticoes” (πέντε στοὰς) represent a porch on each of the four sides and one separating the pools, perhaps separating men and women. Porticoes, like public baths in the ancient world, were open to the public and were gathering places for beggars and other people.

5:3 In these were lying a great multitude of the sick—the blind, the lame, the paralyzed (ἐν ταύταις κατέκειτο πλῆθος τῶν ἀσθενούντων, τυφλῶν, χωλῶν, ξηρῶν). The pools were filled with a large number of the sick, described by three descriptive terms. The second term, “the lame” (χωλῶν), refers primarily to a disability rooted in physical inability (i.e., an improperly functioning body part); the third term, “the paralyzed” (ξηρῶν), refers primarily to a disability rooted in disease (e.g., the term can also mean “withered”).8

The reason nearly all translations move from v. 3 to v. 5 is because what is labeled as v. 4 (which is really vv. 3b–4) in some manuscripts is clearly not original, not only because of its absence from the earliest and best witnesses but also because the manuscripts that do contain it have an unnatural diversity of variant forms.9 According to the NIV in a note, the foreign verse reads after “the paralyzed”: “—and they waited for the moving of the waters. From time to time an angel of the Lord would come down and stir up the waters. The first one into the pool after each such disturbance would be cured of whatever disease he had.” With the abundance of evidence that pagan religion regularly used healing shrines with water as a regular component, it is not unlikely that this tradition is rooted in folk legend, possibly even a popular Jewish tradition.10 Although such folk practices would not have been supported by the Jewish establishment, Theissen is probably correct when he suggests that in this scene “Jesus is in competition with ancient healing sanctuaries.”11 Even beyond its origin, this foreign addition was almost certainly added to explain v. 7.

5:5 And a certain man was there who was lame for thirty-eight years (ἦν δέ τις ἄνθρωπος ἐκεῖ τριάκοντα [καὶ] ὀκτὼ ἔτη ἔχων ἐν τῇ ἀσθενείᾳ αὐτοῦ). In the midst of this great multitude of the sick at this grand place of healing was an unnamed man, “a certain man” (τις ἄνθρωπος), with an unnamed sickness. Although the sickness is not named, v. 8 suggests that he is unable to walk, thus our translation “lame” (ἀσθενείᾳ). The only thing the narrator deems worthy to describe is the length of his lameness: thirty-eight years. The insight into the length of the man’s ailment, especially in light of the absence of other, more key information, suggests that the duration is significant—“it had taken away all hope of a cure.”12 Since the Israelites wandered in the desert before reaching the promised land for thirty-eight years (Deut 2:14), it is often suggested that John is making an intentional allusion to the punishment for their unbelief. But while John may not be unmindful of such an allusion, it is unlikely that such a precise allusion is primarily in mind. This completes the first scene of the plot, the introduction and setting of the pericope.

5:6 When Jesus saw him lying there, and learned that he had already been like that for a long time, he said to him, “Do you want to become well?” (τοῦτον ἰδὼν ὁ Ἰησοῦς κατακείμενον, καὶ γνοὺς ὅτι πολὺν ἤδη χρόνον ἔχει, λέγει αὐτῷ, Θέλεις ὑγιὴς γενέσθαι;). The narrator describes not only that Jesus “saw” (ἰδὼν) him, but that he “learned” (γνοὺς) of his condition, probably by hearing it from another. The implications are potent. Jesus was walking through a great multitude of sick people gathered around what was superstitiously considered to be a sacred place of healing, unrecognized by the sick as the Creator of the universe, the Life (1:3–5).

Jesus asks the man a loaded question: “Do you want to become well?” (Θέλεις ὑγιὴς γενέσθαι;). Although it had been the royal official who initiated conversation with Jesus (4:47–48), this is not the first time Jesus has taken the initiative to help someone (recall the Samaritan woman). But interpreters disagree regarding the intention of the question.13 What issue is Jesus raising with the anonymous lame man? The suggestions offered are varied, including that it is a rebuke, a test of his willingness, or a straightforward question. The variety of suggestions is probably best summarized by admitting with Haenchen that the question is “odd” or at least seems as such to the reader.14 The solution to the intention of this question cannot be found in the answer given by the lame man in v. 7, as if that explained the hidden context out of which the question arose, for he had no clue with whom he was speaking (v. 13). A special divine insight into the man (his psyche?) is disallowed by the narrative itself, which explains that Jesus “came to know” about this man’s condition from others. Even the suggestion by Thomas that the term “well” (ὑγιὴς) carries a Johannine double meaning—both “wellness” and “wholeness”—is disallowed by the narrative, since in 7:23 two different words are used to describe those exact meanings: “Because I made the whole (ὅλον) man well (ὑγιῆ).”

The question is odd because it almost ignores the context so carefully established by the narrative and in which Jesus was standing. It was precisely his desire to become well that had him in that spot, the pool of healing.15 But because Jesus had “learned” about the man and was therefore aware of the place of healing in which he was standing, the question has to mean more. The key might not be in the word “well” but in a word that has become foundational to the Gospel, “become” (γενέσθαι). This word from the prologue onward has been a central term (“came/made/became” [ἐγένετο/γίνομαι]) that expresses the creative work of God in the world. The fact that it is a common Greek word cannot deny its significant use by the Gospel at numerous key junctures (see comments on 1:17). By this term, the reader is able to see into the question with the cosmological insight of the prologue. Jesus is really pursuing the man for healing, but he is also pursuing something much grander.

5:7 The lame man answered him, “Sir, I have no one to put me into the pool when the water stirs up; while I am coming, another goes down before me” (ἀπεκρίθη αὐτῷ ὁ ἀσθενῶν, Κύριε, ἄνθρωπον οὐκ ἔχω ἵνα ὅταν ταραχθῇ τὸ ὕδωρ βάλῃ με εἰς τὴν κολυμβήθραν· ἐν ᾧ δὲ ἔρχομαι ἐγὼ ἄλλος πρὸ ἐμοῦ καταβαίνει). The lame man answers Jesus’s question with respect, denoted by calling him, “Sir” (Κύριε), but responds in a manner that suggests he thinks of Jesus as a simple passerby who is taken with the man and his plight. The lame man responds to Jesus’s question from within his own categories and capabilities and misses the significance of the question about true wellness. It is likely that his language, denoted by the emphatic pronoun, “while I am coming” (ἐν ᾧ δὲ ἔρχομαι ἐγὼ), is an implicit request by manipulation.16 The reader is meant to be struck by the irony. The “one”—the “man” (ἄνθρωπον)—that the lame man needs is standing before him, but the manner of help he will provide is entirely different.

The lame man is fully admissive that he needs help—“I have no one” (ἄνθρωπον οὐκ ἔχω)—but he thinks the solution is in the water just a few feet away with the (magical) stirring that is believed to heal the sick. This verse strongly implies the man believes in some form of superstition and magic, as noted above (see comments on v. 3). It was quite common for a group or individual to believe in magic alongside institutional religion.17 What is significant is that the lame man, like others who held to magic, is convinced that the water was infused with an impersonal power that was still very much from God. In the very city of Jerusalem, in the shadow of the temple, the response of the lame man in this verse “points to an understanding of God as one whose power sometimes operated as an impersonal force occasionally found within the water.”18 It was this that the lame man and the great multitude of sick were waiting for, the magical actions of the God of Israel. This impersonal—even magical—power of God is an important connection between the lame man and the Jewish authorities with whom Jesus is about to come into conflict. In their view, the God they claim to know and the power they believe he enacts are not directly connected, for the power is accessible independent of the direct working of God.

5:8 Jesus said to him, “Rise, pick up your mat, and walk” (λέγει αὐτῷ ὁ Ἰησοῦς, Ἔγειρε ἆρον τὸν κράβαττόν σου καὶ περιπάτει). The confusion spewing from the lame man’s mouth is more imaginary than the magical stirring of the healing water, so Jesus without delay gives a threefold command to the lame man. The Word spoke to the man with the same powerful word that made all creation. The abruptness of Jesus’s command echoes the proclamation that the lame will “leap like a deer” (Isa 35:6). They leap because the Word has spoken. The separation held by the lame man between God and God’s power is coalesced in the person standing before him. By including the command to pick up “your mat” (τὸν κράβαττόν σου), which was a poor man’s bed that could be used as a stretcher, Jesus is establishing for the lame man a new functioning identity.19 He no longer needs to rest his lame body on a mat; all he needs now are soles for his feet. What once carried the man is now to be carried triumphantly by him.20

5:9 And at once the man became well, and he took his mat and walked. But on that day it was the Sabbath (καὶ εὐθέως ἐγένετο ὑγιὴς ὁ ἄνθρωπος, καὶ ἦρεν τὸν κράβαττον αὐτοῦ καὶ περιεπάτει. Ἦν δὲ σάββατον ἐν ἐκείνῃ τῇ ἡμέρᾳ). Without delay, denoted by “at once” (εὐθέως), the lame man was no more; the sickness that had made him lame for thirty-eight years was immediately abolished. Noticeably, the narrative no longer calls him “the lame man” (ὁ ἀσθενῶν) but simply “the man” (ὁ ἄνθρωπος). Fitting the question Jesus raised, the narrator claims the man “became well” (ἐγένετο ὑγιὴς). The use of the significant term “became” (ἐγένετο) is no reflection of the man’s faith but is instead a reflection of the one who made him well and all that this act signifies concerning him. This man was confronted by the man, the final judge, Creator of the universe, the Son of Man—a sign of heaven (cf. 1:51). While waiting for the power of a pool, the lame man was confronted in Jesus by the personal power of God.

What appears like the resolution to the conflict regarding a lame man is given the penultimate position at the end of v. 9 when the narrator notes that this healing was performed on the Sabbath. Several interpreters mistakenly separate vv. 1–9b from vv. 9c–18, as if the healing miracle and the Sabbath controversy are different events. They are most certainly not distinct events that were poorly edited, nor is this a scene change. The same “God confusion” believed by the great multitude of sick is to be made manifest by “the Jews” in what follows. For this reason, what is described in v. 9 is a reflection of the rising conflict, a strategy common to narrative emplotment (see Introduction). The real conflict of the plot includes both geography (the pool of healing) and chronology (the Sabbath).21

5:10 Then the Jews were saying to the man who had been healed, “It is the Sabbath, and it is not lawful for you to carry your mat” (ἔλεγον οὖν οἱ Ἰουδαῖοι τῷ τεθεραπευμένῳ, Σάββατόν ἐστιν, καὶ οὐκ ἔξεστίν σοι ἆραι τὸν κράβαττόν σου). The conflict of the pericope (vv. 6–10) reaches its climax as the chronological placement of the healing gets added to the controversy. The characters known as “the Jews” return to the scene, initiating a dialogue with the “healed” man (see comments on 1:19). The ease with which the healed man and the Jews are included together in the narrative should reflect how the narrative’s introduction of the Sabbath is not “to change the story’s direction,” contra Michaels, but to bring together the two “God confusions” into a coalesced problem.22 The presence of the healed man brings into focus the misperception of an impersonal power of God that Jesus is confronting in both the healed man and the Jews. Even though the healed man now walks, he does not yet truly see; and even though the Jews are the teachers of God, they are still in need of being taught. It is in this way that the pericope climaxes in v. 10.

While the geographic placement (the pool of healing) was more implicit in the pericope, the chronological placement is made explicit. The Jews focus specifically on the day by saying directly, “It is the Sabbath” (Σάββατόν ἐστιν), with “Sabbath” moved forward in the word order for emphasis. The Sabbath regulation is stated clearly: “It is not lawful for you to carry your mat” (οὐκ ἔξεστίν σοι ἆραι τὸν κράβαττόν σου). Based upon the developing oral tradition, it is likely that such a regulation was justified (cf. m. Shabbat 7:2).23 In this pericope, the focus is only indirectly on the Sabbath and its laws, for its direct focus is the God of the Sabbath. The main theme of what follows is not “the violation of the Sabbath” but the violation of the personal power of God.24

5:11 But he answered them, “The one who made me well said to me, ‘Pick up your mat and walk’ ” (ὁ δὲ ἀπεκρίθη αὐτοῖς, Ὁ ποιήσας με ὑγιῆ ἐκεῖνός μοι εἶπεν, Ἆρον τὸν κράβαττόν σου καὶ περιπάτει). In response to their rebuke of his Sabbath-breaking action, the healed man reflects the blame away from himself and places it on his healer, who told him to do it. There is no need to offer a psychological evaluation of the man’s response. He did do as he was commanded by Jesus, whether or not he was aware of what day it was (cf. v. 8). It is important to note that while the Jews excuse the man for following his healer’s orders, they will not excuse Jesus for following his Father’s orders (cf. vv. 17–18).

5:12 They answered him, “Who is the man who said to you, ‘Pick up and walk?’ ” (ἠρώτησαν αὐτόν, Τίς ἐστιν ὁ ἄνθρωπος ὁ εἰπών σοι, Ἆρον καὶ περιπάτει;). The Jews move quickly from the healed man to Jesus. There is a surprising irony surrounding this scene. The healing of a man lame for thirty-eight years is eclipsed in the mind of the Jews by the Sabbath—one day drowns out thirty-eight years! The Jews see a violation, not a miracle. Implicit is their blindness to their own “God confusion.” A man who sits by a pool, waiting for a magical stirring of pool waters goes unquestioned for years (decades) but is questioned on the same day when his healing occurs on the Sabbath. The narrative is begging the reader to ask the right questions about God. Where and when is God expected to work his power? How is God’s power connected to who he is? Apparently, a magical healing pool is considered under the umbrella of God, only as long as it is not done on the Sabbath!

5:13 But the man did not know who he was, for Jesus became invisible in the crowd in that place (ὁ δὲ ἰαθεὶς οὐκ ᾔδει τίς ἐστιν, ὁ γὰρ Ἰησοῦς ἐξένευσεν ὄχλου ὄντος ἐν τῷ τόπῳ). The commotion of the crowd around him, however, caused the healed man to miss the opportunity to identify the person who had healed him. The narrator explains that because of the surrounding crowd, Jesus was able to “became invisible” (ἐξένευσεν), a verb that can imply a turning of the head to dodge or avoid something.25 By describing the crowd “in that place” (ἐν τῷ τόπῳ), the narrator is bringing the narrative back to the opening description of “that place,” the healing pool and great multitude of sick (vv. 2–3), in order to connect the topic with a very different “place”—the temple.26

5:14 After these things Jesus found him in the temple and said to him, “Behold, you have become well. Sin no longer, so that nothing worse may happen to you” (μετὰ ταῦτα εὑρίσκει αὐτὸν ὁ Ἰησοῦς ἐν τῷ ἱερῷ καὶ εἶπεν αὐτῷ, Ἴδε ὑγιὴς γέγονας· μηκέτι ἁμάρτανε, ἵνα μὴ χεῖρόν σοί τι γένηται). After an undisclosed amount of time, denoted again by “after these things” (μετὰ ταῦτα), the narrator records how Jesus found the healed man in the temple. The temple is a logical place for Jesus to be during a Jewish festival; he may have been heading to the temple when he stopped by the great multitude of sick lying near the healing pool, which is just north of the temple. The temple is also a logical place for the healed man to be drawn toward, especially after he had just been divinely healed! Beyond all the logic, the fact that Jesus “found” (εὑρίσκει) the healed man suggests it is not a chance encounter. Jesus frequently “finds” the people he is looking for (cf. 1:43, and especially 9:35).

After the pronouncement “you have become well” (ὑγιὴς γέγονας), repeating the verb so central to this Gospel (bringing back into focus Jesus’s original question and the deep sense his question was intending to probe; see comments on v. 6), Jesus gives his fourth and final command to the healed man: “Sin no longer” (μηκέτι ἁμάρτανε). While the present imperative can view the prohibition as an ongoing process and could be translated as “stop sinning,” yet since it primarily views action from an internal point of view it is more commonly used for general precepts, “for habits that should characterize one’s attitude or behavior—rather than in specific situations.”27 It is therefore best translated as a general prohibition. This helps avoid an interpretation that is searching for a specific disease-causing sin in the life of the healed man rather than a general command against sin. Following the prohibition against sin, an appeal is added: “So that nothing worse may happen to you” (ἵνα μὴ χεῖρόν σοί τι γένηται). This purpose-result clause warns the healed man of greater consequences from his sin if he does not heed Jesus’s prohibition.

This verse has raised more than a few questions. It is the first time sin is directed at a particular person and the first time sin is mentioned since 1:29, where Jesus was described as the one who would take away the “sin of the world.” While some have tried to press from this prohibition and purpose-result clause a direct connection between sin and consequence (in this case, illness), it can only be done so in light of the rest of the teaching of Scripture. It is clear that sin has its consequences and that sickness (and death) can be one of its consequences, but this verse is not addressing directly this issue.

In light of this larger context of wellness, the issue of sin Jesus is addressing is not to be confined to a deed done on one day but is sin rooted in habits that characterize a person, the kind of sin that is detrimental to true wellness. For behind all the concern for geography and chronology in this pericope, there was a “God confusion” that entirely misunderstood the personal nature of the power of God. The healed man truly believed God could and did heal, but he was looking for it in the depersonalized magical waters rooted in superstition and folklore. In the same way, the Jews truly believed that God could and did heal. But when they were confronted with a real healing, they raised no questions regarding the divine origin of Jesus’s power but focused entirely on the perceived Sabbath violation. In a manner similar to the superstition of the multitude of the sick, “The Jews think Jesus capable of accessing God’s power outside the will of God . . . independent of the direct working of God.”28

It is with this context in mind that Jesus’s prohibition and subsequent warning is to be explained. The sin Jesus is concerned with is defined elsewhere by the Fourth Gospel as “the unwillingness to believe that Jesus is the one in whom God—the Father—is revealed and through whom God’s power works.”29 For example, in 8:24 and 16:9, sin is defined as not believing in Jesus. And in 15:24, it is made even clearer: “The essence of sin is to see the power of God at work through Jesus and yet refuse to acknowledge that power as evidence of the self-revealing action of God in Jesus.”30 Thus, the command to stop sinning is an admonition against the sin of unbelief, which in this case manifests itself by regarding God’s power as operating in impersonal independence from the working of God, a problem for both the healed man and the Jews. Our interpretation is in no way limiting the immediate consequences of sin but following the Gospel narrative by locating the deep root of sin as a rejection of God (idolatrous “God confusion”). The immediate consequences of sin are merely a symptom of the larger sin problem. Jesus has a concern for the man that extends far beyond flesh and bones; it is a concern that the man’s healed condition might be “worse” than the first (cf. Matt 12:45).

5:15 The man went and reported to the Jews that Jesus was the one who made him well (ἀπῆλθεν ὁ ἄνθρωπος καὶ ἀνήγγειλεν τοῖς Ἰουδαίοις ὅτι Ἰησοῦς ἐστιν ὁ ποιήσας αὐτὸν ὑγιῆ). The depiction by the narrator does not paint the healed man favorably, as if he now believed or moved closer to belief. Even with his own body as evidence, the healed man represents a particular response to the Gospel that replaces the power of God with impersonal and superstitious religion and fails to believe in Jesus, the personal manifestation of the power of God. It is in this way that the conflict of the pericope comes to a resolution. Verses 14–15 are part of the resolution because they bring completion to the “become well” theme that began in v. 6 at the beginning of the conflict.

5:16 And for this reason the Jews were persecuting Jesus, because he was doing these things on the Sabbath (καὶ διὰ τοῦτο ἐδίωκον οἱ Ἰουδαῖοι τὸν Ἰησοῦν, ὅτι ταῦτα ἐποίει ἐν σαββάτῳ). The Jews take the report from the healed man and announce by their actions their condemnation of him. The narrator’s comments describe their response as in process, denoted by the imperfect tense “were persecuting” (ἐδίωκον), which might even suggest it had become a fixed policy at this stage in Jesus’s ministry. There is no denial of his power, only the charge that it took place illegally, “on the Sabbath” (ἐν σαββάτῳ). For the first time in the Gospel, the ministry of Jesus, which until now has been primarily centered upon individuals, is turning public—and hostile (see 1:11).

5:17 But Jesus answered them, “My Father is working up to the present, and I too am working” (ὁ δὲ Ἰησοῦς ἀπεκρίνατο αὐτοῖς, Ὁ πατήρ μου ἕως ἄρτι ἐργάζεται, κἀγὼ ἐργάζομαι). Although there is no statement made by the Jews, Jesus “answered” (ἀπεκρίνατο) them according to their condemnatory actions.31 Jesus’s answer is both a confession and a declaration. His reference to “my Father” (Ὁ πατήρ μου) would have probably sounded strange to the Jews but is perfectly at home in the Fourth Gospel (see 1:18). He had spoken of “my Father” once before when he said in the temple, “Stop making my Father’s house a house of business!” but it did not register (2:16). This time it does, and they are beginning to grasp its implications (cf. v. 18).32

Jesus explains that his Father “is working up to the present” (ἕως ἄρτι ἐργάζεται), with no indication that the time has come or soon will come for work to stop. The idea that God “rested” after creating the world in six days (Gen 2:2–3) should not be interpreted to mean that God is now inactive. God not only created the whole world; he also sustains it. In this sense, “breaking” the Sabbath is not only lawful for God; it is necessary. From what can be determined from Jewish exegesis, it is likely that this declaration by Jesus to the Jews would have been quite understandable, fitting comfortably alongside the current exegesis of God’s Sabbath rest.33 The “resting” of God was comfortably defined as an anthropomorphism, for God has never ceased his creative and sustaining activity.

It is not just God who has been working, for Jesus can also claim, “I too am working” (κἀγὼ ἐργάζομαι). The emphatic pronoun “I too” (κἀγὼ) not only equates Jesus’s work with God’s but also equates Jesus with God (cf. v. 18). Although the Jews do not have the reader’s insight from the prologue that Jesus is the one through whom all things were made (1:3), he too must also be working. Jesus’s inclusion of himself is not without mystery, for it is difficult to know the exact interrelation of their coparticipatory “work.” Even still, Jesus’s primary point is clear: both the Father and the Son are at work. Thus, Jesus is not violating the Sabbath but “is acting as God’s agent to do what no one denied God could do on the Sabbath.”34 Whatever issues were raised regarding the Sabbath have been trumped by this theological explanation of the work of God, the Father and the Son. In light of this pericope, then, the working that Jesus is doing must include the healing of the lame man on the Sabbath and should also be understood to incorporate his entire mission and ministry.

It is important to note that the “present” working of God speaks directly against the false conception that God’s power can be disassociated from his person. This false belief made it possible from the lame man’s perspective for there to be a healing pool that had only a loose association with God and according to the Jews for Jesus to use God’s power contrary to God’s will. This verse, therefore, is a specific rejection of the assertion that Jesus had access to God’s power (as evidenced by the healing) but applied it in an inappropriate manner (i.e., on the Sabbath). Bryan offers this interpretive translation: “My Father has not set his power loose in the world to be accessed as an independent force; if his power is at work in the world, it is because my Father is personally at work.”35 The Jews were confronted with a stark reality. The entire event surrounding the healed man was not only directly connected to the person of Jesus but also connected—and necessarily so—to God himself.

5:18 And for this reason the Jews were seeking to kill him even harder, not only because he broke the Sabbath, but also because he called God his Father, making himself equal with God (διὰ τοῦτο οὖν μᾶλλον ἐζήτουν αὐτὸν οἱ Ἰουδαῖοι ἀποκτεῖναι, ὅτι οὐ μόνον ἔλυεν τὸ σάββατον ἀλλὰ καὶ πατέρα ἴδιον ἔλεγεν τὸν θεόν, ἴσον ἑαυτὸν ποιῶν τῷ θεῷ). By their actions, the Jews show that they fully understand what Jesus is communicating about himself and at the same time have revealed an entirely inadequate understanding of God. By misunderstanding Jesus, the Jews are by definition misunderstanding—even rejecting—God, who is ironically the one they are attempting to defend. Their concerns over the Sabbath have long dissipated, for this Sabbath breaker was more than just licentious in their eyes. He was blasphemous and therefore deserving of death. While the author continues to unfold for the reader the historical events surrounding the life and ministry of Jesus, the cosmological insights provided by the prologue prepared the reader for such statements by Jesus (cf. 1:1, 14, 18) and such a reaction to him (1:11). Only now, however, are the insights being viewed for the first time in three dimensions and in color.36 Ironically, the very people that “were seeking to kill him” (ἐζήτουν αὐτὸν ἀποκτεῖναι) happen to be the same ones for whom he came to die.

Theology in Application

In an encounter with a man lame for nearly four decades, Jesus probes the nature of true wellness and the problem of real sin, all the while confronting the religious superstitions and false conceptions about God so common in the fallen world. In this pericope, the reader of the Fourth Gospel is exhorted to explore the nature of wellness, the consequences of sin, and more importantly, the right questions about who God is and the kind of work he is doing.

Religious Superstition and Our Conception of God

By interlocking two different interlocutors by means of an identical problem, this pericope made manifest the ease with which humans can make God to be something he is not or to connect something to God that is not from him. Both the lame man and the Jews were guilty of disconnecting God from his power. This ironic disconnect in the shadow of the temple in Jerusalem is too common a problem in the church today. This pericope is urging the reader to ask the right questions about God.37 Where and when is God expected to work his power? How is God’s power connected to who he is? Any answer to those questions that removes the work of Jesus is immediately false. In a real way, this passage is encouraging us, the church, to be self-critical, to put ourselves to the test by taking captive “hollow and deceptive philosophy” that depends on “[our own] human tradition and the elemental spiritual forces of this world rather than on Christ” (Col 2:8). It is because we believe in Christ that we distrust ourselves, knowing full well that we continually need him even as he continually works (v. 17).

Sin and Afflictions

This pericope raises the unavoidable question of the afflictions caused by personal sin. Although we argued that Jesus’s command to “sin no longer” (v. 14) was speaking more generally about habitual and characteristic sin that produces consequences in eternity, this in no way divorces our current afflictions from our sin. In fact, if we were to separate our afflictions from our sin, we would be committing the same “God confusion” believed by the healed man and the Jews. In a very real way, our afflictions are a direct effect of our sin, even if we cannot precisely define the cause and effect. But our response is not overly to examine sources and symptoms but to be disciplined by our afflictions as by God. Calvin encourages this response: “First, then, we must acknowledge that it is God’s hand that strikes us and not imagine that our ills come from blind fortune. Next, we should ascribe this honour to God, that as He is indeed a good Father He has no pleasure in our sufferings and therefore does not treat us harshly unless He is displeased with our sins.”38 In hindsight, Jesus’s interaction with the lame man and the Jews is filled with paternal love, and as we look back on our afflictions, we are likely to see the same paternal love embracing our moments of suffering. For this reason, we are exhorted by the Lord himself: “Sin no more!”

The Personal Power of God

In this pericope, Jesus is portrayed as a coparticipant in the work of God; a work now best described as the work of the Father and the Son. A correct conception about God locates the true work that God is doing in the person of Jesus Christ and therefore in the work he has accomplished for the world on the cross. To speak of God in a generic or “spiritual” sense is not to speak of the God of the Bible. The work of God is so intertwined with the work of the Son that Jesus is the personal power of God. Where and how is God working? Quite simply, he is working through the work initiated by Jesus Christ, which he himself will finish upon his return.

Let the church check itself to ensure it has not taken on a “work” that is not of God, that is, not rooted in and commanded by Jesus Christ. Even more, let the church check itself to ensure it has not excluded a “work” that Christ did perform simply because it seems less spiritual. The calling of the church is to embrace the work of Christ as their Great Commission (Matt 28:18–20), a work that is from the Father and empowered by the Spirit (20:21–23).