Chapter 17

John 7:53–8:11

Literary Context

The narrative moves from an intense dialogue between Jesus and a complex array of interlocutors to a heated scene involving legal and religious politics regarding a woman, who is presumed guilty of adultery, and Jesus, who is presumed guilty of insurrection and heresy. This is the final scene of the section of the Gospel entitled “the Confession of the Son of God” (5:1–8:11), in which the authoritative establishment of Judaism finally comes to understand that neither cultural shaming nor legal challenge will stifle the radical ministry activity of Jesus.

- IV. The Confession of the Son of God (5:1–8:11)

- A. The Third Sign: The Healing of the Lame Man on the Sabbath (5:1–18)

- B. The Identity of (the Son of) God: Jesus Responds to the Opposition (5:19–47)

- C. The Fourth Sign: The Feeding of a Large Crowd (6:1–15)

- D. The “I AM” Walks across the Sea (6:16–21)

- E. The Bread of Life (6:22–71)

- F. Private Display of Suspicion (7:1–13)

- G. Public Display of Rejection (7:14–52)

- H. The Trial of Jesus regarding a Woman Accused of Adultery (7:53–8:11)

Main Idea

Jesus is the true Judge of humanity, “the one without sin,” who receives on behalf of the world the condemnation of his own law. This is the grace and love of the gospel. The only acceptable response is to live under the gracious law of Christ, which seeks the promotion of justice and the demotion of sin.

Translation

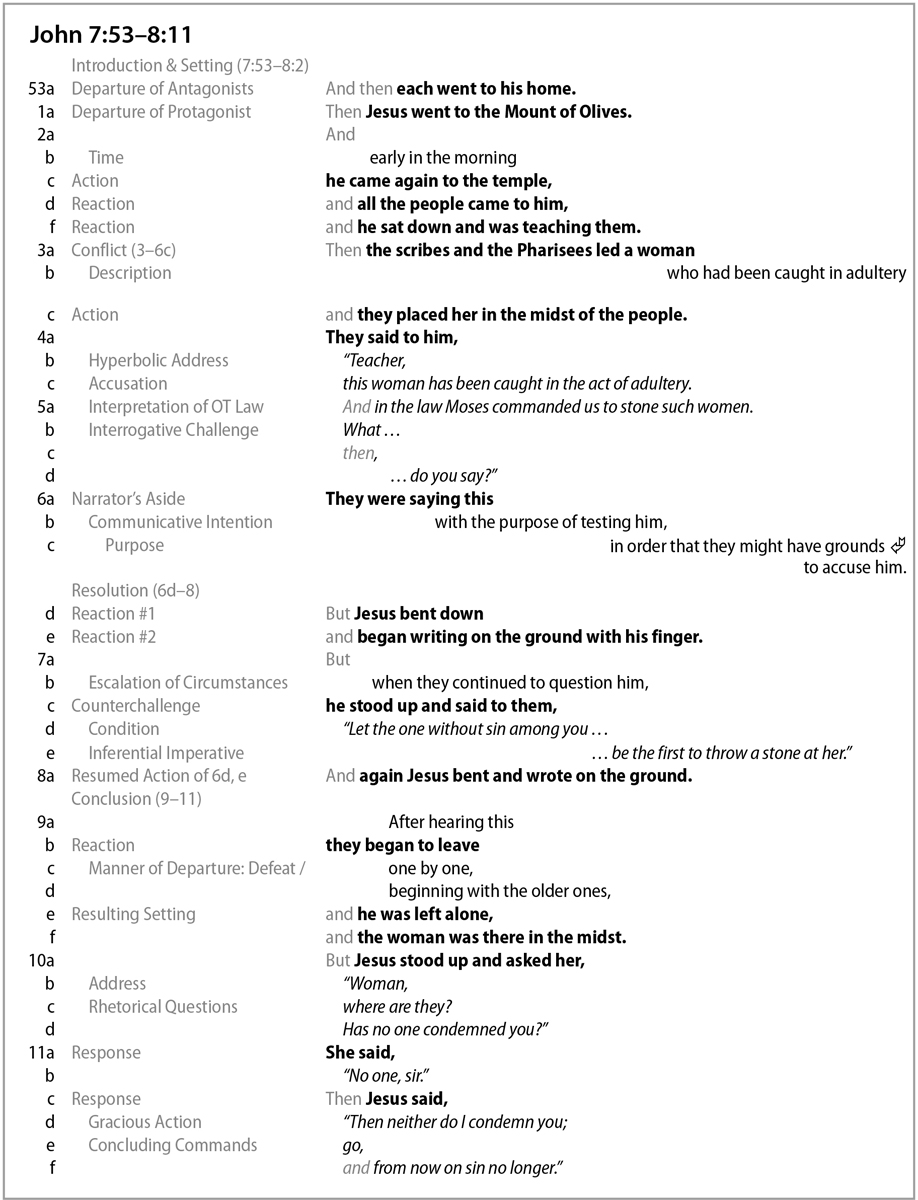

Structure and Literary Form

This pericope corresponds to the basic story form (see Introduction). The introduction/setting is established in 7:53–8:2, explaining the location, setting, and people around whom the plot’s conflict will focus. In 8:3–6a the conflict of the pericope is set before Jesus, centering upon a woman, adultery, and the law of Moses. In 8:6b–8 the conflict is given resolution by a single statement of Jesus framed by a symbolic action of Jesus. Finally, 8:9–11 offer the conclusion/interpretation to the pericope of the woman accused of adultery, with a clear depiction of the gospel of Jesus Christ made possible by the authoritative activities of the true Judge.

Exegetical Outline

- H. The Trial of Jesus regarding a Woman Accused of Adultery (7:53–8:11)

- 1. Teaching in the Temple (7:53–8:2)

- 2. The Law of Moses and Adultery (vv. 3–6a)

- 3. The Finger of God (vv. 6b–8)

- 4. The Law of Christ (vv. 9–11)

Explanation of the Text

Since this pericope is strongly questioned in regard to its connection to the original version of the Gospel of John, many view it as an addendum, a later addition to the Gospel narrative (see below). Yet in spite of this text-critical mystery, this pericope plays a significant role in the developing narrative, serving as a conclusion to several burgeoning issues in chapter 7 and as the climactic episode to the section, “The Confession of the Son of God” (5:1–8:11), by clearly showing to the Jewish authorities the authority of Jesus. As the received and contemporary form of the Gospel today, the story guides the reader to see in climactic fashion the confession of Jesus and his mission to the world.

7:53 And then each went to his home ([Καὶ ἐπορεύθησαν ἕκαστος εἰς τὸν οἶκον αὐτοῦ). The narrative transitions from v. 52 to v. 53 by showing the departure of the “high priests and Pharisees” (including Nicodemus) after the dialogue at the end of the last pericope. It might also be inclusive of all the people of Jerusalem—“the crowd”—with 8:1–2 depicting the return of normality in Jerusalem after the celebration of the Feast of Tabernacles. The narrative closes the previous scene emphatically, thus highlighting the final verbal exchange between the Jewish leadership and Nicodemus. It therefore left some explanatory details regarding the conclusion of the Feast for this pericope. It is mentioned here simply to show that a new encounter is about to take place. It is an abrupt transition and often viewed as evidence of its interpolation, but its abruptness is not entirely strange to John.

8:1 Then Jesus went to the Mount of Olives (Ἰησοῦς δὲ ἐπορεύθη εἰς τὸ Ὄρος τῶν Ἐλαιῶν). This verse is unique in John, for it is the only place that the Mount of Olives is mentioned in the Gospel, a location more commonly mentioned in the Synoptics. The Mount of Olives was located near Jerusalem, so Jesus had not travelled far from the celebration of the Feast. Interestingly, the Mount of Olives may have been Jesus’s primary residence (see Luke 21:37). Thus, while the crowd went to their homes, Jesus went to his.

8:2 And early in the morning he came again to the temple, and all the people came to him, and he sat down and was teaching them (Ὄρθρου δὲ πάλιν παρεγένετο εἰς τὸ ἱερόν, καὶ πᾶς ὁ λαὸς ἤρχετο πρὸς αὐτόν, καὶ καθίσας ἐδίδασκεν αὐτούς). The crowd’s interest in Jesus at the Feast had not subsided, nor had the political concerns regarding Jesus led to a change in public opinion. Rather, early the next morning Jesus was in the temple “again” (πάλιν), teaching all the people—just as he had done upon his arrival at the Feast (7:14). The content of the teaching is not provided by the narrator. In this scene it is not the content of Jesus’s message but his actions that are important for interpretation (see vv. 6b, 8).

By mentioning “all the people” (πᾶς ὁ λαὸς), the narrator introduces the immediate audience for the situation with the woman accused of adultery, explaining the identity of the group in whose midst she will stand (v. 3). This is also an important detail in regard to the stoning of an idolater under Jewish law, which required that the witnesses should raise their hands against the sinner first, followed by the hands of “all the people” (Deut 13:9; 17:7).13 This concludes the introduction and setting of the pericope.

8:3 Then the scribes and the Pharisees led a woman who had been caught in adultery and they placed her in the midst of the people (ἄγουσιν δὲ οἱ γραμματεῖς καὶ οἱ Φαρισαῖοι γυναῖκα ἐπὶ μοιχείᾳ κατειλημμένην, καὶ στήσαντες αὐτὴν ἐν μέσῳ). The conflict of the pericope is introduced in dramatic fashion. The teaching of Jesus was interrupted by the Jewish authorities who had with them a woman accused of adultery. The Pharisees are well known to the reader (see comments on 1:24), but this is the first and only mention of “the scribes” (οἱ γραμματεῖς) in the Gospel. While scribes could often be members of the party of the Pharisees, they are not to be equated. Scribes occupied a skilled and important profession in Judaism, functioning as a combination of roles: lawyer, ethicist, theologian, catechist, and jurist.14 For the purpose about to be explained by the narrative, the presence of the scribes along with the Pharisees is warranted. Their presence makes formal the legal proceedings about to take place.

Beside the formality of their purposeful entrance, the scribes and Pharisees are quickly eclipsed by the unnamed person they forcefully brought with them. Like several significant characters in the Gospel, this woman is unnamed. Her name becomes a title that describes her actions—befitting the focus on actions in this pericope. The narrator describes her as “a woman who had been caught in adultery” (γυναῖκα ἐπὶ μοιχείᾳ κατειλημμένην).15 The description is vague. It is possible that she was caught in the act of adultery, a requirement if her stoning was to have appropriate evidence, but the narrative does not reveal such detail. It is also just as probable for the reader to assume that the entire situation is a setup, given the character of the Jewish leadership displayed thus far. Even beyond this woman, why Jesus? No reason is given why the Pharisees do not try again to arrest him (cf. 7:30, 32, 44), which they apparently had ample reason to do (cf. 5:16, 18).16

Great care must be taken to grasp the true conflict of this pericope. The pericope is often given a title that focuses on the woman, usually in regard to the crime of adultery. There is some warrant for this. But how we define her is significant. The narrator’s description need not mean anything more than that she has been accused of adultery, just as the description of the entrance of the Jewish authorities need not mean they had good intentions or were honestly concerned with the law (and v. 6 will make clear that this was not the case). Whatever the evidence was against the woman, the judgment has not yet been given. And the need for and expectation of judgment has been laid literally at the feet of Jesus. At this moment Jesus was being challenged, not with words but with action. As much as the woman had been “led” (ἄγουσιν) and “placed” (στήσαντες) before Jesus—terms that depict the treatment of a prisoner—in this pericope it is Jesus who is on trial as the named defendant.

8:4 They said to him, “Teacher, this woman has been caught in the act of adultery” (λέγουσιν αὐτῷ, Διδάσκαλε, αὕτη ἡ γυνὴ κατείληπται ἐπ’ αὐτοφώρῳ μοιχευομένη). The legal proceedings begin with the accusation against the woman, that she “has been caught” (κατείληπται) committing adultery, with the perfect tense verb making the charge certain. According to Jewish law, such an accusation would require eyewitnesses, which are implied by the additional detail that the act of adultery was witnessed while “in the act” (ἐπ’ αὐτοφώρῳ), a term only used here in the NT that matches the specific requirement of the law that the adulterers must “be found” (Deut 22:22).

The scribes and Pharisees call Jesus “Teacher” (Διδάσκαλε), a word befitting the legal proceeding into which Jesus has now been included. The only other group that uses that title for Jesus is comprised of his disciples (cf. 1:38; 11:28; 13:13, 14; 20:16). The narrator in 1:38 even uses the title “Teacher” to interpret the title “Rabbi.” In light of the intentions of the scribes and Pharisees shortly to be revealed (v. 6), such a title recalls Jesus’s dialogue with Nicodemus, who spoke with cloak-and-dagger intentions by means of the same courteous title. In the context of first-century Judaism, the title of “Teacher” was connected to the spiritual guides of the people, the “scribes,” who were the only teachers of the people in matters of religion and therefore religious law (see comments on 3:2). The use of the title here, then, is politically loaded, matching their true intentions about to be revealed.

8:5 “And in the law Moses commanded us to stone such women. What, then, do you say?” (ἐν δὲ τῷ νόμῳ ἡμῖν Μωϋσῆς ἐνετείλατο τὰς τοιαύτας λιθάζειν· σὺ οὖν τί λέγεις;). After describing the crime of the woman, the scribes and Pharisees give strong commentary regarding the law. They state emphatically that “Moses commanded us” (ἡμῖν Μωϋσῆς ἐνετείλατο), which serves as a forceful and coercive expectation of the result they desire—her death. The woman is again unnamed. This time she is even spoken of derogatorily, “such women” (τὰς τοιαύτας), reflecting that her identity is now defined representatively by a notorious group: adulterers.

The commentary by the scribes and Pharisees contains a significant omission. The law to which they refer states clearly that both the woman and the man are to be stoned (Lev 20:10; Deut 22:22). It is also worth noting a significant addition. The law is not as specific as the scribes and Pharisees suggest regarding the manner of execution. Stoning is only prescribed for the guilty pair when the woman is “a virgin pledged to be married” (Deut 22:23–24). But the man is not present. It is therefore hard not to see the unfolding scene as an intentional lynching of the woman.17 The scribes and Pharisees conclude their case with a question addressed to Jesus: “What, then, do you say?” (σὺ οὖν τί λέγεις;). There is no need for us to try to reconstruct the outcome of Jesus’s possible responses. The intent was to twist and slander from the start, and they would have used any data provided. The question is ironic, for the one they are trying to set up is the Judge (5:22).

8:6a They were saying this with the purpose of testing him, in order that they might have grounds to accuse him (τοῦτο δὲ ἔλεγον πειράζοντες αὐτόν, ἵνα ἔχωσιν κατηγορεῖν αὐτοῦ). The conflict is given a conclusion by the narrator, who makes the scribes and Pharisees’ intentions clear so that the reader not misunderstand the unfolding drama. The narrator reveals that the intentions of the scribes and Pharisees were focused on Jesus (not the woman) in order to test him. Quite simply, they were seeking grounds “to accuse him” (κατηγορεῖν αὐτοῦ). Jesus had neither been sought out for guidance nor to serve as a member of the scribal authorities; Jesus was the one on trial. And the accusation against the woman was to serve as a pretext for a greater accusation against Jesus.

8:6b But Jesus bent down and began writing on the ground with his finger (ὁ δὲ Ἰησοῦς κάτω κύψας τῷ δακτύλῳ κατέγραφεν εἰς τὴν γῆν). The resolution offered to the conflict by Jesus is communicated by means of an action. After lowering or situating himself nearer to the ground,18 Jesus “began writing” (κατέγραφεν), with the beginning of the action given emphasis by an ingressive imperfect.19 He did not write on paper but “on the ground” (εἰς τὴν γῆν), a general term that in this context is referring to the dirt or sand.20 Jesus did not write with pen but “with his finger” (τῷ δακτύλῳ), denoted by a dative of means (instrumental dative).21

It is at this point that the history of interpretation takes a strong detour, focusing entirely on what Jesus was writing in the dirt. This unique response by Jesus has led to scores of interpretive guesses. Was he writing a response from Scripture, like one or all of the Ten Commandments? Or was he writing a response regarding the accusers, like their own sins (so Jerome)? Or was his writing intended to display a rhetorical response, like for a space of silence or to create a dramatic effect?22 But such an approach—a focus on the what—misunderstands not only the action of Jesus but also the movement of the pericope.

The focus of the pericope is not on what Jesus wrote on the ground but that he wrote on the ground. The narrator has already been shown to be speaking through action and symbolism. The emphasis was not on the content of Jesus’s teaching but on the act of him teaching (v. 2); not on any detailed content about the unnamed woman and the accusation against her (Where was the man? Who are the witnesses?) but on the symbolic action displayed through her treatment (v. 3). The narrator’s description of Jesus’s action of writing on the ground is no less intentional or symbolic here. The narrator is crafting an image for the reader—an “impression” (see Introduction)—that is its own communication. Helpfully, the reader is not left alone to determine the symbolism. The key is in the additional phrase “with his finger” (τῷ δακτύλῳ).23 Our interpretation of this key phrase and the contextualization of this act must wait until the full response of Jesus has been examined, especially since the act is repeated in v. 8.

8:7 But when they continued to question him, he stood up and said to them, “Let the one without sin among you be the first to throw a stone at her” (ὡς δὲ ἐπέμενον ἐρωτῶντες [αὐτόν], ἀνέκυψεν καὶ εἶπεν αὐτοῖς, Ὁ ἀναμάρτητος ὑμῶν πρῶτος ἐπ’ αὐτὴν βαλέτω λίθον). The description of the scene by the narrator suggests that the continued questioning by the scribes and Pharisees intensified the dramatic nature of the encounter. Rising from the ground, Jesus makes only one statement. Jesus speaks a command in the third person, which can easily get confused in English with a permissive idea: “Let the one . . . throw a stone” (βαλέτω λίθον).24 But it is not a request; it is a forceful command. Who is qualified to throw a stone at this woman, that is, to judge her? One qualification characterizes this person: “The one without sin” (Ὁ ἀναμάρτητος). This comparative adjective is used with an elative sense, which means it is not technically making a comparison but expressing a quality that by means of the adjective is intensified.25

The force of the command, then, is that Jesus is commanding judgment to take place by a sinless one—literally, one who is entirely without sin. This is not a denial or rejection of the law, for the statement only demands that this single qualification be met “first” (πρῶτος). It is, rather, a demand for the right—even perfect—execution of the law. This statement spoke past the legal maneuvering right into the heart of the scribes and Pharisees, who at that moment could not sidestep their own law or Lawgiver. These are the only words spoken by Jesus in response to the public scene at hand.

8:8 And again Jesus bent and wrote on the ground (καὶ πάλιν κατακύψας ἔγραφεν εἰς τὴν γῆν). The resolution concludes with this final, framing comment by the narrator, who again describes Jesus bending down and writing on the ground. The action itself, let alone the narrative’s repetitive emphasis of it, is striking to say the least. The parallel with v. 6b is potent, especially in light of the two components that are missing. First and more obvious, the tool for writing, “with his finger” (τῷ δακτύλῳ), is not mentioned. Second and undetectable in English translation, the lexical form of the term for “writing” is different. In v. 6b, “writing” (κατέγραφεν) contains a prefix not found in the verb used in v. 8’s “writing” (ἔγραφεν). The significance is not that the words mean different things; they are, in fact, functionally synonymous. Rather, they signal to the reader that a more important symbolic connection is being communicated. It is worth stating that we are not just interpreting the action of an event but the narrator’s depiction (i.e., his interpretation) of the event, which supplied the emphatic focus on Jesus’s “finger.”

It is the term “finger” that forges the connection, for according to Exodus 31:18/Deuteronomy 9:10, the Ten Commandments were written by “the finger of God.” The argument for this connection is twofold.26 First, in the context of the scene as whole and in v. 5 specifically, Jesus is being challenged to stand opposed to Moses in his assessment of the required punishment regarding one of the Ten Commandments. For this reason, the mention of “finger” intentionally places Jesus in Moses’s position, even more, eclipsing the legal authority of Moses with that of Jesus.

Second and more directly, the two lexical forms of the term for “writing” that appear in vv. 6b and 8 are a perfect match to Exodus 32:15 (LXX); the two different lexical forms (one containing the prefix) with synonymous meanings occur in the same pericope referring specifically to the writing of the law given to Moses on stone tablets. Given the fact that the prefixed form of “writing” (κατέγραφεν) only occurs here in the NT, the intentional connection to Exodus 32:15 is only strengthened. In light of the allusion to the finger/writing of the Ten Commandments by God in the Old Testament, the symbolic significance of the action of Jesus, then, is that he himself is the author of the law, and his finger is the very “finger of God.” When the scribes and Pharisees challenge Jesus with the legality of the law of God, they are speaking directly to its author.27

8:9 After hearing this they began to leave one by one, beginning with the older ones, and he was left alone, and the woman was there in the midst (οἱ δὲ ἀκούσαντες ἐξήρχοντο εἷς καθ’ εἷς ἀρξάμενοι ἀπὸ τῶν πρεσβυτέρων, καὶ κατελείφθη μόνος, καὶ ἡ γυνὴ ἐν μέσῳ οὖσα). The conclusion and interpretation of the pericope begins with a description by the narrator of the aftermath of Jesus’s statement and further symbolic action. Without any continued confrontation, the crowd—presumably both the scribes and Pharisees as well as “all the people” (v. 2) who had come to hear Jesus teach—“began to leave” (ἐξήρχοντο), denoted by an ingressive imperfect that conveys the nature of their departure. The narrator adds two further details regarding this departure. First, they left “one by one” (εἷς καθ’ εἷς). Second, they left “beginning with the older ones” (ἀρξάμενοι ἀπὸ τῶν πρεσβυτέρων). These descriptions emphasize the “dramatic and ceremonious” nature of the departure (cf. Ezek. 9:6).28

The narrator carefully describes the two people that remain: Jesus and the woman. Jesus is described as “alone” (μόνος) to emphasize the fact that only he met his own qualification; only he was “the one without sin” (v. 7). The woman is also described carefully as still “in the midst” (ἐν μέσῳ), which we left awkwardly translated so as to match its earlier use and to allow the narrative to return dramatically to her person and presence. She had not moved an inch, and yet everything around her had changed dramatically. The only constant was Jesus, who was still kneeling just above the ground upon which he had written—at her level.

8:10 But Jesus stood up and asked her, “Woman, where are they? Has no one condemned you?” (ἀνακύψας δὲ ὁ Ἰησοῦς εἶπεν αὐτῇ, Γύναι, ποῦ εἰσιν; οὐδείς σε κατέκρινεν;). Just as Jesus rose to address the legal experts, he now rises to address the accused. By addressing her as “woman” (Γύναι), Jesus is doing nothing more impersonal or harsh than he did to his own mother (see 2:4; 19:26). In fact, its use in this context is fitting. The normal use of the term demands that it be seen to function at least minimally as a distancing mechanism, even if it is enveloped within a healthy and loving relationship (see comments on 2:4). Even though Jesus has already come to the defense of this woman, he is not technically on her side. He alone is “the one without sin.” The title, “woman,” depicts brilliantly how Jesus can embrace our sinfulness without the slightest hint of capitulation. According to his own qualification (v. 7), Jesus is the perfect Judge (5:22). Jesus asks the woman two questions that are difficult to interpret. Is this true surprise or gentle sarcasm?29 Jesus’s statement in v. 11 makes clear the woman is not innocent. The questions focus the reader’s attention on his status as the Judge and on his authority to render a judgment in regard to her and her sinfulness.

8:11 She said, “No one, sir.” Then Jesus said, “Then neither do I condemn you; go, and from now on sin no longer” (ἡ δὲ εἶπεν, Οὐδείς, κύριε. εἶπεν δὲ ὁ Ἰησοῦς, Οὐδὲ ἐγώ σε κατακρίνω· πορεύου, [καὶ] ἀπὸ τοῦ νῦν μηκέτι ἁμάρτανε]). The woman’s answer is simply an acknowledgement of the direction of Jesus’s questions: there is no other Judge. This is not a statement of faith but simply a statement of fact. Jesus would have to explain his judgment.

The pericope ends with a final, two-part statement by Jesus. First, Jesus declares that he does not condemn her. Here, as in v. 10, Jesus speaks of condemnation in a legal sense. In this statement is found the paradox of the gospel of Jesus Christ. For since the one who wrote the law is also the judge that presides over it, everything in between—freedom and condemnation, life and death—is under his authority (5:26–27; cf. Luke 4:18–19; 5:24).30

This explains, then, the second part of Jesus’s statement. Jesus sends the woman away—free, but not without qualification. Since he is still Judge, she must live accordingly. She must live as one under the law of God (and of Christ; cf. Gal 6:2). As will shortly be announced in the pericope to follow, true freedom is found in Christ (8:31–38), which serves as further evidence that this pericope fits comfortably where it sits. It is in this way that the pericope presents its conclusion and interpretation.

Theology in Application

In this short and text-critically disputed pericope, the grace of the gospel of Jesus Christ is dramatically displayed in regard to a woman accused of adultery. What begins as a trial of an unnamed woman becomes a trial of Jesus, and what starts in the law of Moses becomes entirely about the law of Christ. In this pericope the reader of the Fourth Gospel is exhorted to sit under Jesus the Judge, who is both the author of the law and the authority over it, and to view their sin in light of his person and work.

Jesus the Judge

This pericope declares the legal status and functional authority of Jesus. Jesus is the “finger” of God, the true Judge, and his law—the law of Christ—is the foundation for all humanity (Gal 6:2). The concern of the scribes and Pharisees regarding adultery was eclipsed by Christ the Judge’s concern for all sin. Christ is concerned with the deep-rooted and selfish sins inside every person. The gospel of Jesus Christ is not self-help instruction but the good news about real sin, the sin for which only God can help.31 That is why the author of Hebrews can exhort us to entrust ourselves to Jesus, our high priest. “For we do not have a high priest who is unable to empathize with our weaknesses, but we have one who has been tempted in every way, just as we are—yet he did not sin” (Heb 4:15). That is why, then, the courtroom of God our Judge is described as containing “the throne of grace,” so that we may approach “with confidence” and “receive mercy and find grace to help us in our time of need” (Heb 4:16). The church lives under this law of Christ, under the ruling authority of this high-priestly Judge, under whom even the most demanding law of God is drenched in the grace of the cross of Christ. This law then is freedom, not burden, and we have moved away from slavery to sin and been propelled by grace to embrace this righteousness (Rom 6:15–23).

The Law of Christ and Human Authority

This pericope describes the divine foundation for all law and dealing with sin. It emphasizes the “finger of God” behind all the legal proceedings of humanity. This is in no way a repudiation of the legal authority of humans or human institutions but is instead an explanation of the source and nature of that authority. The law of Christ is intended to pervade all human authority, serving in, around, and through the justice displayed to those around us.

It is in the church that this kind of authority makes itself more prominently known. The church is even more concerned with true justice but expresses it in two unique ways. First, the Christian expects justice not just of others but first and foremost of oneself. Justice is what God requires, and the judging authority given to humans and their institutions is entirely derivative. Second, the Christian locates the justice (of God) within the grace (of God).32 This is what makes the cry for justice by the Christian—individual or institution—look so different, so Christian; it does not come from selfish motives but “from above” and does not stand by human hands but by the “finger” of God.

“Sin No Longer”

The concluding exhortation of Jesus to the woman accused of adultery is a command to “sin no longer” (v. 11). It is a gracious command to live life in freedom. The gospel of Jesus Christ proclaims a remarkable paradox. The author of the law of God and the Judge of humanity is also the one who receives the punishment. The giver of life embraces death for us; “the one without sin” becomes sin for us. This is grace and love—this is good news. For this reason the Christian strives to embrace the law, the law of Christ, in every way. To do this is to submit to sin no longer and instead to submit to Christ.33 The exhortation of Christ, then, calls out to the reader as it did the woman by looking forward to the glorious future, all the while looking back to the humble memory of the past. It sees, then, the law of the gospel of Christ in all things and behind every aspect of life, for Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today, and forever (Heb 13:8).

The Reliability of the Bible

The actual (textual) science used to offer a level of confident certainty in the original form of the Bible can undercut that confidence for those whom such technical issues are a cause for fear. This need not be the case. The pastor or teacher should use this text to reaffirm the reliability of the Bible, using the human fingerprints across every page of the Bible to discuss its natural integrity and truthfulness. This is not time for a lesson in textual criticism. The issues surrounding this pericope demand that the pastor speak about inspiration, about canon, about the human authorship of Scripture, and yet also about providence, about church history and tradition, and about the divine authorship of Scripture. A paradox similar to the gospel discussed above occurs here: mere humans wrote words that are the very Word of God. This requires some analysis and explanation from the academic but it also requires some reflection and adjudicating from the pastor-shepherd. The goal of such a discussion would not be absolute certainty but appropriate faith in a trustworthy object we know today as the Bible.