Chapter 29

John 14:1–14

Literary Context

This pericope is the second of eight sections of the farewell discourse. Surrounded by a prologue (13:31–38) and an epilogue (16:25–33), the farewell discourse can be divided into six significant and developing thematic statements by Jesus, with each offering comfort and consolation for the disciples from Jesus, befitting the nature of a farewell discourse (see comments before 13:1). These six statements within the farewell discourse offer one long exhortation to stay the course and encouragement that their efforts will be matched by the Trinitarian God himself. In the first of these six statements, Jesus firmly establishes his identity and his relation to the Father, which serves to explain not only the path he must take but also the path his disciples will follow. In this well-known “I am” statement by Jesus, the entire force of the Gospel lands powerfully on his person and work. The disciples—and the readers—are exhorted to consider afresh the magnitude of the person and work of Jesus, in order that they may find their true rest (v. 1) and true home (vv. 2–3) and, on the way, their true vocation (vv. 12–15).

- VII. The Farewell Discourse (13:1–17:26)

- A. Introduction: The Love of Jesus (13:1–30)

- 1. Jesus and the Washing of His Disciples’ Feet (13:1–20)

- 2. Jesus Announces His Betrayal (13:21–30)

- B. The Farewell Discourse (13:31–16:33)

- 1. Prologue: Glory, Departure, and Love (13:31–38)

- 2. I Am the Way and the Truth and the Life (14:1–14)

- 3. I Will Give You the Paraclete (14:15–31)

- 4. I Am the True Vine (15:1–17)

- 5. I Have Also Experienced the Hate of the World (15:18–27)

- 6. I Will Empower You by the Paraclete (16:1–15)

- 7. I Will Turn Your Grief into Joy (16:16–24)

- 8. Epilogue: Speaking Plainly, Departure, and Peace (16:25–33)

- C. Conclusion: The Prayer of Jesus (17:1–26)

- A. Introduction: The Love of Jesus (13:1–30)

Main Idea

Jesus Christ, who alone is the way, the truth, and the life, exhorts his disciples to find through faith in his person and work their true rest, their true home, and their true vocation.

Translation

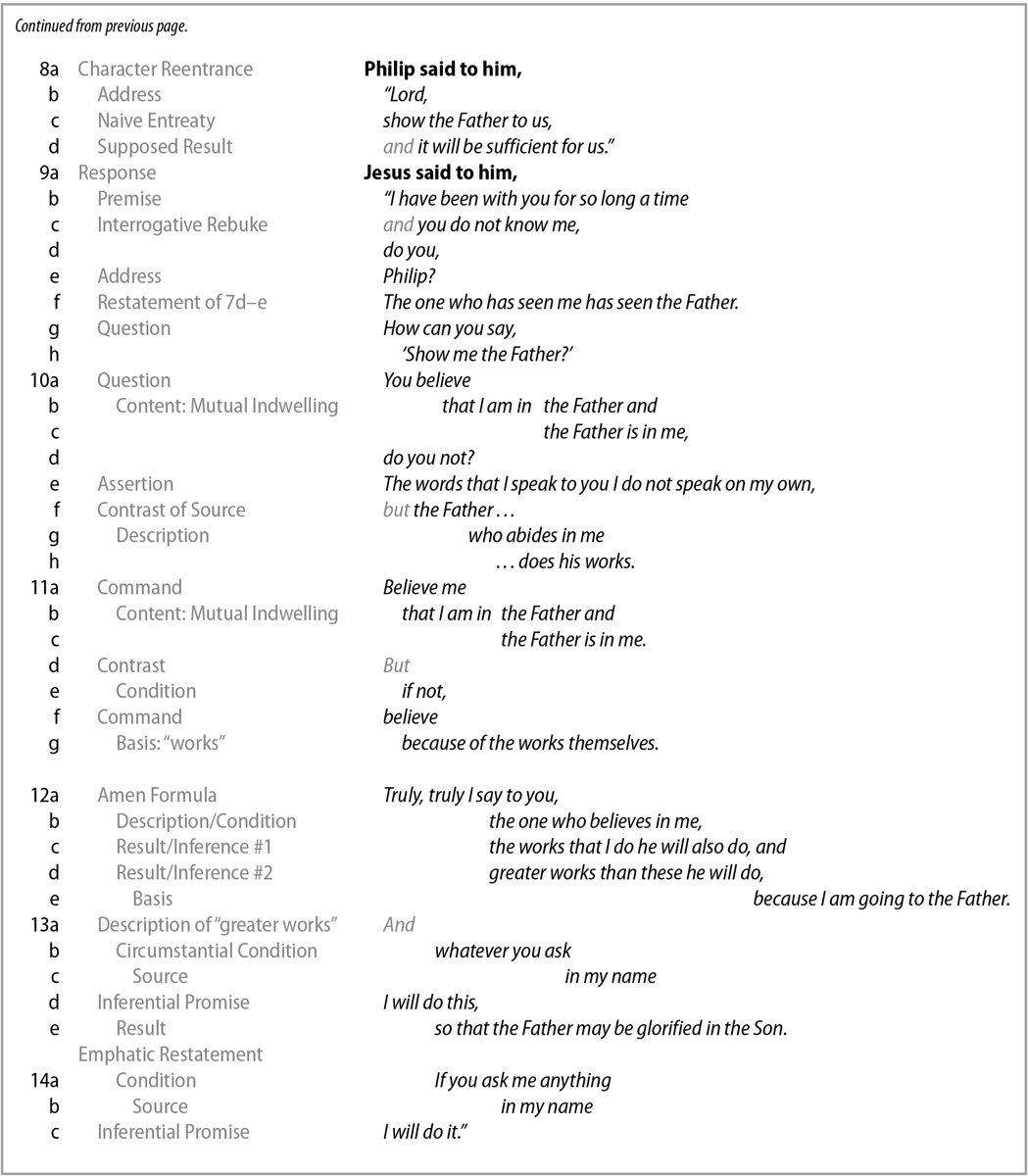

Structure and Literary Form

As the second of eight sections of the farewell discourse, this pericope is part of the fourth (and longest) substantial monologue in the narrative proper. A monologue (see Introduction) is similar to a dialogue in that it is set in the context of an engagement and conflict, but rather than engaging point-for-point it allows for a lengthy argument. A monologue can contain elements of rhetoric, challenge, and conflict, but it does so in a sustained presentation.

This pericope is the first of six statements by Jesus intending to exhort and encourage his disciples. While all of 14:1–31 works together (see comments on 14:27–29), a transition occurs after v. 14, warranting a section break. In this first statement Jesus reveals the future rest and future work he has established for his disciples, both of which have been founded in the unique identity of Jesus Christ.

Exegetical Outline

- 2. I Am the Way and the Truth and the Life (14:1–14)

- a. “I Go and Prepare a Place for You” (vv. 1–4)

- b. Not just a Place but a Person—the “I Am” (vv. 5–7)

- c. The Father, the Son, and “the Works” in the Name of the Son (vv. 8–14)

Explanation of the Text

Since this entire section of the Gospel and “the farewell discourse” proper is replete with interpretive issues, we refer the reader to the first pericope of this section where we provided an overview of the nature (genre), literary structure, and function of the farewell discourse (see comments before 13:1).

14:1 “Do not let your heart be frightened. Believe in God; believe also in me” (Μὴ ταρασσέσθω ὑμῶν ἡ καρδία· πιστεύετε εἰς τὸν θεόν, καὶ εἰς ἐμὲ πιστεύετε). In the first section of the pericope (vv. 1–4), Jesus begins by exhorting his disciples to trust him as he explains what is soon to take place. Jesus commands his disciples not to “be frightened” (ταρασσέσθω), a verb which refers to an inward turmoil or confusion.1 Since the imperative mood is addressing an emotional state, it is best taken as a command to “be in control of yourself.”2 Jesus is addressing their inner person, their “heart” (ἡ καρδία), ministering to his disciples by addressing them from their own point of view.3

After commanding them to remove fear from their heart, Jesus commands them to receive in its place the confidence that comes from a more appropriate and worthy foundation and security: belief in God. The two occurrences of “believe” (πιστεύετε) could grammatically have several possible combinations of imperatives and indicatives (e.g., indicative-imperative or imperative-imperative), but are more likely continuing the imperative force of the previous phrase.4 It is less likely that an indicative would be sandwiched between two imperatives than three imperatives would be working emphatically together.5 Jesus is not assuming their belief in God (indicative: “You believe in God”) and hoping to add belief in him (imperative: “Believe also in me”)—as if belief in God and Jesus could ever be separated (a foreign thought to this Gospel and Scripture as a whole). Rather, Jesus is assuaging their fears by commanding them to believe in God, the one made known and accessible by Jesus Christ, demanding that their belief in God be fully established in him.

14:2a “In my Father’s house there are many rooms” (ἐν τῇ οἰκίᾳ τοῦ πατρός μου μοναὶ πολλαί εἰσιν). Jesus then begins to describe the foundation upon which belief in God is built. He starts by using two terms that need to be defined carefully, for they direct much of the discourse to follow: my Father’s “house” (οἰκίᾳ) and many “rooms” (μοναὶ). We will discuss them in turn.

The term “house” (οἰκίᾳ) is a spatial metaphor that has already been used in the Gospel to refer to a building where one dwells (cf. 11:31; 12:3). Jesus even used the full phrase “my Father’s house” in 2:16 when referring to the physical temple in Jerusalem, though that is not the particular reference in this case. There are three other ways the term can be used. First, befitting its previously mentioned reference to the temple but placing it in this particular context, some have suggested that the imagery in vv. 2–3 is referring to a heavenly temple, drawing from an elaborate collection of similar language in the OT and other Jewish literature that portrayed the temple as the eschatological dwelling place of the followers of God.6 Second, some have interpreted the term in a more personal and spiritual sense to refer to a “family” or “household,” a use not foreign to the Gospel (cf. 4:53; 8:35). Third, the more traditional interpretation and the one to be preferred interprets the spatial metaphor as simply referring to the heavenly abode of God and therefore to the promised abode of the children of God. While all three interpretations are dependent on the interpretation given to the second term, “rooms” (μοναὶ), we can already identify difficulties with the first two options: the first interprets the metaphor too tightly (too physically), and the second interprets a clearly spatial metaphor too loosely (too spiritually). In a sense, both interpretations inappropriately fuse the historical and cosmological realities so important to the Gospel.

The term “rooms” (μοναὶ) is also a spatial metaphor and gives further expression to the “house” metaphor discussed above. The Greek term is a cognate of the verb “remain,” “abide,” or “dwell” (μένω), a significant term in the Gospel (see ch. 15). It generally refers to a dwelling place or, more simply, a room. The common translation “mansions” (KJV), which is filled with inappropriate associations, is based upon the Latin Vulgate’s mansiones, which more simply refers to “stations” and “resting places.”7 Similar to the previous metaphor, some interpret “rooms” too rigidly, suggesting that there is a series of progressive and temporary steps up which one advances until perfection is ultimately attained (e.g., Origen).8 But this idea is entirely foreign to the Gospel. A more contemporary interpretation, based on the use of the same term in 14:23, interprets “rooms” too loosely by suggesting it refers to spiritual relationships: “Not mansions in the sky, but spiritual positions in Christ, much as in Pauline theology.”9 But to define the Father’s “house” and presence by means of the people of God is to reverse the movement of the entire Gospel. No, it is the people of God who one day will be with the Father, just as the Son—the Word—in the beginning was “with God” (1:1).

Without denying the level of complexity presented to us by this verse, it is important that we not miss its overt simplicity. Jesus begins the discourse proper by telling the disciples of their inheritance, and invites them, heirs of the eternal house of God (8:35), to visualize and embrace even now the bountiful blessings offered to the children of God. Jesus depicts how every Christian—man or woman, slave or king in this world—will have a place to dwell with God. The focus of this text is wrongly applied to the “rooms” because of the frequent translation, “mansions.” The focus of this text is not merely the place but the person; as Jesus said, each Christian will dwell in “my Father’s house.” The good news is not fully manifest at Christmas, when God came to us and dwells with us, but at the new creation when we are taken to God and dwell with him.

14:2b “If it were not so, would I tell you that I am going to prepare a place for you?” (εἰ δὲ μή, εἶπον ἂν ὑμῖν ὅτι πορεύομαι ἑτοιμάσαι τόπον ὑμῖν;). After offering such powerful hope, the phrase that follows in the text of v. 2 is difficult to explain with certainty.10 The aorist verb “I tell” (εἶπον) could have been translated as referring to a time in the past when Jesus had already spoken about such things, but Jesus never explicitly made such a statement up to this point in the Gospel. There is a growing consensus, however, that Greek tense does not technically refer to the time of an action. Although it is common to assume that an aorist verb refers to a past-time event, the verbal aspect in this context allows this verb to speak for a present action (i.e., the dramatic aorist).11 There is a clear and related example of this use of the aorist in 13:31, where Jesus declares with two aorist-tense verbs: “Now (Νῦν) the Son of Man is glorified (ἐδοξάσθη), and God is glorified (ἐδοξάσθη) in him.” Thus, Jesus here asks a question not in reference to a previous teaching (even an implicit one) but as a way of reinforcing and substantiating the statement he just made.12

It is significant that Jesus claims to be going “to prepare a place” (ἑτοιμάσαι τόπον) for his disciples. Some interpreters find this statement awkward. If there are already “many rooms,” why is there need for preparation? Jesus is not merely going to prepare a place, for the “going” is itself the preparation. The term “going” has become a technical term in the Gospel for the final journey of the mission of the Son. The cross, resurrection, and ascension to the Father is the preparation, the provision of permanent dwelling with God.13 That is how Jesus is never fully departing, for his going is for the purpose of fellowship and communion with God—eternal life. That is also why the discourse proper must be viewed as encouraging. This is not to deny a real (i.e., in space and time) “place” (τόπον) that will be occupied by the people of God or to minimize the physical place as anything other than an indisputable and extremely important fact.14 Rather, it is to say that the “place” is not an end in itself but a symptomatic expression of the reality of life in and with God (see comments on vv. 5–7). Just as the Word was “in the beginning,” so shall we be in the end “with God” (1:1).

14:3 “And if I go and prepare a place for you, I will come again and take you with me, in order that where I am you also may be” (καὶ ἐὰν πορευθῶ καὶ ἑτοιμάσω τόπον ὑμῖν, πάλιν ἔρχομαι καὶ παραλήμψομαι ὑμᾶς πρὸς ἐμαυτόν, ἵνα ὅπου εἰμὶ ἐγὼ καὶ ὑμεῖς ἦτε). Jesus presses the logic of his encouragement even further by drawing the following conclusion: his departure is intended to provide a departure for his disciples as well. The third-class condition (ἐὰν plus the subjunctive) is best understood to refer to certain fulfillment.15 The certainty of Jesus’s purposeful departure—the death, resurrection, and ascension to the Father—serves as a guarantee of his return for his disciples, the people of God. Just as certainly and physically as Jesus came to the world, he will come again. And when he comes again, he will “take” or “receive” (παραλήμψομαι) his disciples for this one purpose (denoted by the telic use of ἵνα): that they “may be” (ἦτε) where “I am” (εἰμὶ ἐγὼ). The emphatic “I am,” one of several informal “I am” statements (see comments on 6:35), is intended to magnify God as the place of dwelling. In a real way, God’s ultimate purpose is for us to “be” with the one who simply “is.”

Jesus’s exhortation to believe and hope-filled encouragement is the groundwork for the doctrine of eschatology.16 But the Gospel’s depiction of this eschatology has two important aspects.17 First, this is the clearest example of a statement by Jesus regarding his second coming in all four Gospels. Jesus declares here the truth that the church has long proclaimed regarding the return of Christ. Jesus is promising the disciples that he, the Good Shepherd, will come and gather his sheep (ch. 10). Since “the end” is safely grounded in the one who was “in the beginning” (1:1), we may “not let our heart be frightened” but “believe” in the purposeful plan of God (v. 1). This truth—eschatology—is not merely something for which we wait expectantly; it is also something for which we live purposefully.

Second, as much as this eschatological encouragement is future, its meaning is not contained by a future event, for it is grounded in the very personal presence of God. The promise of Jesus is not to leave them and wait for them at the other end but to come back to them, to receive them, and to take them to the place where he is.18 This aspect of eschatology is significant, for it speaks not merely of the future (the end) but also of the present. Jesus really is speaking of a place—there is a “where” (ὅπου); yet the most important factor is when he speaks of his person—the “who.” For the Christian this means that the entire ministry presence of Christ is eschatological, for eschatology properly understood is the manifest presence of Christ, from the incarnation to the new creation.19 It is for this reason that Jesus will make clear in the discourse to follow that God is present even in his absence. For at this moment the disciples are not merely being informed about the “last things” but about living (eschatologically) in the new covenant.20

14:4 “And where I am going, you know the way” (καὶ ὅπου [ἐγὼ] ὑπάγω οἴδατε τὴν ὁδόν). The first section of this pericope (vv. 1–4) is concluded by a final exhortation by Jesus. To reinforce their belief in God and him (v. 1), Jesus reinforces what they already know: the “where” (ὅπου) and “the way” (τὴν ὁδόν). The disciples should know that the place where Jesus is “going” is the cross (and resurrection/ascension). The implication of Jesus’s statement is that the “where” (the cross) is also “the way,” or the “where” and “the way” are mutually explanatory.21 Just as Jesus has preparatory work to do to accomplish his purposes, so here he prepares his disciples, involving them in the process that not only serves them but includes them. As Augustine explains, “He is in a certain sense preparing the dwellings by preparing those who are to dwell in them.”22 Ultimately, “the way” (τὴν ὁδόν) contains a necessary ambiguity (of which the readers, not the disciples, should be aware) in that it addresses not a literal road or path or even a set of directions but a (metaphorical) “way” of life, a certain kind of life (see comments on 12:26), or more fully, the goal of human life.23

14:5 Thomas said to him, “Lord, we do not know where you are going. How are we able to know the way?” (Λέγει αὐτῷ Θωμᾶς, Κύριε, οὐκ οἴδαμεν ποῦ ὑπάγεις· πῶς δυνάμεθα τὴν ὁδὸν εἰδέναι;). A transition to the second section of the pericope (vv. 5–7) is provided and introduced by Thomas’s question, who claims not to know either the “where” or “the way.” The interrelation between them discussed above (v. 4) demands that knowledge of the one is knowledge of the other; thus, Thomas’s dual confusion is truly only a single, even if multifaceted, confusion. That is why Jesus’s answer can be a single, multifaceted answer (v. 6). Hoskyns is right to suggest that the narrator does not introduce this brief dialogue with Thomas simply to record a conversation but “to extract a precise statement of that faith,” that “way”/kind/goal of life by which the disciples have access to God.24

14:6 Jesus said to him, “I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me” (λέγει αὐτῷ ὁ Ἰησοῦς, Ἐγώ εἰμι ἡ ὁδὸς καὶ ἡ ἀλήθεια καὶ ἡ ζωή· οὐδεὶς ἔρχεται πρὸς τὸν πατέρα εἰ μὴ δι’ ἐμοῦ). Thomas’s question provides the opportunity for Jesus to make one of the most well-known statements in all Scripture. Jesus defines exactly what the “the way” is, and it is not what but who. Jesus is the way. But Jesus does not just link the way to himself, but also the truth and the life—a threefold expression of his person and work. This is the sixth of seven formal “I am” statements in the Gospel, each containing “I am” (Ἐγώ εἰμι) and a predicate (see comments on 6:35). These seven formal “I am” statements are emphatic descriptions of the person and ministry of Jesus and cumulatively form a detailed picture of Jesus Christ.

It is difficult to define with precision the meaning of this threefold “I am” statement. Noting the contextual focus on “the way,” some have suggested that “the way” is the key term, with the other two nouns standing in apposition to explain the first noun.25 But as much as “the way” has been the leading term thus far in the pericope, in the “I am” statement all three nouns are syntactically coordinated into a multifaceted unity. The development is logical. Jesus had been giving a definition of “the way” that was multifaceted and complex and which found its meaning in his person and work. Thomas’s question, then, is not simply about an abstract “way” but about Jesus. Thus Jesus answers not merely about a place or direction but about his person. For this reason the definition of each of these nouns—way, truth, life—cannot be left to abstraction but must be grounded directly in Jesus. The entire Gospel is needed to explain Jesus, for these three nouns speak in a language that is rooted more in foreground (Christology) than background (abstract concepts) and are reflective of the grand subject matter of Scripture.26

This does not mean, however, that we cannot give any definition to this threefold “I am” statement. It simply means that our definition must guard against truncating or diluting the fullness of the object in view. It also means that the terms cannot be defined in abstraction, for they are cumulatively interdependent and interrelated and present concretely in Jesus who is simultaneously the way, the truth, and the life.27 With this in mind we can offer a summary of this threefold “I am” statement: as “the way,” Jesus is the mode; as “the truth,” Jesus is the reality; as “the life,” Jesus is the source.

Jesus is “the way” in that he is the (only) mode by which the Christian existence and participation in God are made possible and accessible. Jesus fulfills this by means of his death, resurrection, and ascension to the Father. While “the way” for Jesus is quite literal and physical—entailing suffering and death—for the Christian, as we discussed above (v. 4), “the way” is less a road or path and more a “way of life,” a goal, or even the mode in which the Christian now functions.28

Jesus is “the truth” in that he is the reality through which Christian existence and participation in God are confirmed and find their meaning. Jesus fulfills this by embodying the supreme revelation. Jesus is the standard for what is real in this world and true about God, for he is the one who reveals God (1:18). Jesus, the Son of God, says and does exclusively what the Father has given him to say and do (5:19; 8:29). He is ultimately the perfect expression of God (1:14). For this reason Jesus is the plumb line for all things—seen and unseen, the lens through which the world is to be interpreted and by which it must be judged. He is the gracious extension of light (reality) into a world confined by darkness (distortion).

Jesus is “the life” in that he is the source through which Christian existence and participation in God are founded and given their origin. Jesus fulfills this by being the supplier of life and existence, the Creator of all living things—without whom “not one thing came into existence that has been made” (1:3). Jesus is the beginning and was “with God” in the beginning and is God, the second person of the Trinity. Jesus is life itself (1:4), is the one who has life in himself (5:26), is the one who defines life even over death, for Jesus is “the resurrection and the life” (11:25). Since Jesus is “the life,” all the dichotomies are broken that have been created between life and death, this life and the life to come, the seen and the unseen.

Jesus destroys the wall that divides humanity from God (the way), denies the falsehood that distorts humanity in relation to God (the truth), and defeats the last and greatest enemy of humanity, death (the life).29 He is the totality of what God has done, is doing, and will do. This is why Jesus concludes his “I am” statement with such an exclusive summary: “No one comes to the Father except through me” (οὐδεὶς ἔρχεται πρὸς τὸν πατέρα εἰ μὴ δι’ ἐμοῦ).30 This may be the most disturbing claim in all Scripture, and to some this statement is problematic. But as Koester explains, “ ‘Except’ is like a window that lets light into a closed room. . . . Rather than restricting access to God the word ‘except’ indicates access to God.”31 When Jesus declares that he is “the way and the truth and the life,” he offers to humanity—every single person—God’s gift to the world. This is the epitome of “good news” and is the opposite of being restrictive or exclusive, for it is true freedom (8:36).

14:7 “If you have known me, you will know my Father also. From now on you know him and have seen him” (εἰ ἐγνώκατέ με, καὶ τὸν πατέρα μου γνώσεσθε· καὶ ἀπ’ ἄρτι γινώσκετε αὐτὸν καὶ ἑωράκατε αὐτόν). Jesus concludes his formal “I am” statement with a promise and an invitation.32 The conditional statement is intended to connect Jesus’s person and work with the Father. The disciples’ knowledge of the Father in the future is directly connected to their experience of and relationship to Jesus in the present. This is why Jesus commands them to believe not only in him but also in God (v. 1), for the two persons, the Father and the Son, form a single object of faith—God.

Here Jesus does not merely explain to the disciples (via Thomas’s question) what they should have known about the Father (and therefore the Son) but also exhorts them to respond—“from now on” (ἀπ’ ἄρτι)—to what they now know and have seen of the Father in the person and work of the Son.33 Everything must be different “from now on,” for the revelation of God has been dramatically declared by the Word-become-flesh. The prologue announced that Jesus would reveal the Father (1:18), and “now” the disciples have been told in the most explicit terms that when they see Jesus they are seeing God. “In short, He both exists unchangeably in Himself and inseparably in the Father.”34 And it is into this perfect union that the Son and the Father (by the Spirit) invite the disciples to share and coexist; the children of God with the unique Son and the Father (1:12, 14, 18). This is “the way and the truth and the life” (v. 6).

14:8 Philip said to him, “Lord, show the Father to us, and it will be sufficient for us” (λέγει αὐτῷ Φίλιππος, Κύριε, δεῖξον ἡμῖν τὸν πατέρα, καὶ ἀρκεῖ ἡμῖν). A transition to the third section of the pericope (vv. 8–14) is introduced by another question, this time from Philip, who correctly interprets in Jesus’s statement a connection between “seeing” the Father and the work of Jesus, but in a manner that inappropriately disassociates the Father from the person of Jesus. Jesus is about to strongly rebuke this confusion, for it not only misunderstands how the children of God “see” the Father but more importantly how the children of God relate to the Father through his unique Son, Jesus Christ. In this final section of the pericope, Jesus addresses these confusions. In vv. 9–11 Jesus will rebuke and correct Philip’s misunderstanding by showing the inherent unity between the person of the Father and the person of the Son, and in vv. 12–14 Jesus will show even further the inherent connection that now exists between the work of the Father and Son and the work of the children of God.

It is important to note the exact words Philip uses in the question he addresses to Jesus. Speaking on behalf of the disciples as a whole, Philip requests that Jesus “show the Father to us” (δεῖξον ἡμῖν τὸν πατέρα). Was he expecting some theophany comparable to what Moses saw when he similarly requested of God, “Show me your glory” (Exod 33:18)?35 As Jesus is about to declare, Philip’s truncated understanding of “seeing” the Father stifles not only his view of Jesus but also his understanding of Christian existence. Not only does Philip misunderstand how Jesus “shows” the Father but also what a “sufficient” experience of the Father truly is.36 Philip’s question then, especially coming from one who had been with Jesus from the beginning (see 1:43–46), reveals not only a limited perspective of Jesus but also a limited perspective of the Christian life.

14:9 Jesus said to him, “I have been with you for so long a time and you do not know me, do you, Philip? The one who has seen me has seen the Father. How can you say, ‘Show me the Father?’ ” (λέγει αὐτῷ ὁ Ἰησοῦς, Τοσούτῳ χρόνῳ μεθ’ ὑμῶν εἰμι καὶ οὐκ ἔγνωκάς με, Φίλιππε; ὁ ἑωρακὼς ἐμὲ ἑώρακεν τὸν πατέρα· πῶς σὺ λέγεις, Δεῖξον ἡμῖν τὸν πατέρα;). Jesus responds to Philip’s statement with a question that serves as a rebuke. The form of the Greek negation “not” (οὐκ) signals that the question expects an affirmative answer. The question could be translated more like a statement: “I have been with you for so long a time and still you do not know me!” The rebuke and the explicit mention of their participation with Jesus “for so long a time” (Τοσούτῳ χρόνῳ) suggests that Philip—and all the disciples—should have known who he was and therefore the one he represents (cf. 1:18). Jesus asks Philip not one rebuking question but two, with the second question pressing further the assumption that Philip should have “known” the connection between Jesus and the Father from his participation “with” (μεθ’) Jesus during his earthly ministry.

These two rebuking questions serve as a frame around the central statement by Jesus that summarizes the subject matter of his ministry: “The one who has seen me has seen the Father” (ὁ ἑωρακὼς ἐμὲ ἑώρακεν τὸν πατέρα). Jesus has spoken directly of this before (see comments on 12:45; cf. 13:20). Jesus is the ultimate expression of God and the visible manifestation of God (1:18). The prologue has already announced such a relationship (see comments on 1:1, 14), and the entire Gospel has depicted the ministry of the Trinitarian God in the person of Jesus Christ in the world. This is why Philip’s vision for what was “sufficient” was so insufficient, for life “with him” is “the vision of God.”37 In the person of Jesus, the Father could not have been more fully made known or shown.

14:10 “You believe that I am in the Father and the Father is in me, do you not? The words that I speak to you I do not speak on my own, but the Father who abides in me does his works” (οὐ πιστεύεις ὅτι ἐγὼ ἐν τῷ πατρὶ καὶ ὁ πατὴρ ἐν ἐμοί ἐστιν; τὰ ῥήματα ἃ ἐγὼ λαλῶ ὑμῖν ἀπ’ ἐμαυτοῦ οὐ λαλῶ· ὁ δὲ πατὴρ ἐν ἐμοὶ μένων ποιεῖ τὰ ἔργα αὐτοῦ). Jesus now presses Philip and by implication the other disciples (and the readers) with a question that again assumes an affirmative answer. The question is a restatement of the same subject matter: “I am in the Father and the Father is in me” (ἐγὼ ἐν τῷ πατρὶ καὶ ὁ πατὴρ ἐν ἐμοί ἐστιν). The statement in v. 9 emphasized the manifestation of the Father by the Son, whereas here the emphasis is centered upon the relational unity between the Father and the Son.

The twofold use of the preposition “in” (ἐν) speaks unavoidably of the mutuality of the Father and the Son, rooted in what the church has long expressed by its Trinitarian theology.38 As much as there is a distinction in person between the Father and the Son, there is a clear and essential functional overlap, commonality, and unity. The language here even speaks of a mutual indwelling or mutual interpenetration of the Father and Son, which although might be taken to refer to the divine essence is clearly referring to the mode of revelation, for the Father has revealed himself “in” Jesus.39 Both the words of the Word as well as his actions reflect the abiding presence of the Father. Everything Jesus is, has said, and has done is itself also an expression not only of or about the Father but even by the Father. While we can differentiate the persons of the Father and the Son, the Father and the Son maintain a functional inseparability through the person and work of the Son.

14:11 “Believe me that I am in the Father and the Father is in me. But if not, believe because of the works themselves” (πιστεύετέ μοι ὅτι ἐγὼ ἐν τῷ πατρὶ καὶ ὁ πατὴρ ἐν ἐμοί· εἰ δὲ μή, διὰ τὰ ἔργα αὐτὰ πιστεύετε). Jesus concludes his focus on the inherent unity of the Father and the Son (vv. 9–11) by commanding belief in this unified presence and activity of the Father and the Son. The imperative verb “believe” (πιστεύετέ) demands that Christians submit to this truth, and the subordinating conjunction “that” (ὅτι) stresses that the belief be focused not just on a person but on the proposition of the functional unity of the Father and the Son.40 That is, Christian belief is located not only in the person of the Son but also in the message of the Son.

Jesus suggests the “works” (ἔργα) of God as an alternate object of belief beyond the word of God. In this Gospel the “works” of Jesus act as “signs” (see comments on 2:11). The works of Jesus point beyond themselves to their true subject matter, the person and work of God made known through Jesus Christ. Both the words and works of Jesus reveal who he is—who God is—and serve as witnesses for belief in God. The works make clear that the Son is “in the Father and the Father is in” him, showing concretely what the prologue announced about the unseen (cf. 5:36; 10:25, 38).

14:12 “Truly, truly I say to you, the one who believes in me, the works that I do he will also do, and greater works than these he will do, because I am going to the Father” (ἀμὴν ἀμὴν λέγω ὑμῖν, ὁ πιστεύων εἰς ἐμὲ τὰ ἔργα ἃ ἐγὼ ποιῶ κἀκεῖνος ποιήσει, καὶ μείζονα τούτων ποιήσει, ὅτι ἐγὼ πρὸς τὸν πατέρα πορεύομαι). Beginning with an authoritative preface (see comments on 1:51), Jesus transitions from the works of the Son of God to the works of the children of God (vv. 12–14). Jesus states clearly that “the works that I do he will also do” (τὰ ἔργα ἃ ἐγὼ ποιῶ κἀκεῖνος ποιήσει). This statement is dependent on their belief in Jesus, but it transitions the believer from being a witness of to being a participant in the works of God.41 In this way Jesus makes a promise to the disciples that is rooted in their position “in Christ” (to use the apostle Paul’s terminology). A comparison between the Father-Son and the Son-children is important to note. The Father and Son are mutually indwelling and interpenetrated, whereas the children of God are dependent on the Son. Moreover, the Father and Son share the same essence and function, whereas the children and the Son only share the same function. Faith in Christ is not merely a passive act, it is also active; it is to become a participant in the power and mission of God and in some way to share in the ministry of God through Christ.

Jesus adds to the promise a statement that has raised interpretive confusion: “And greater works than these he will do” (καὶ μείζονα τούτων ποιήσει). From early on in the early church, the “greater works” have been interpreted as the missionary success of the disciples, often including accompanying miraculous works.42 But certainly the children of God cannot be said to do “greater works” than the unique Son. The additional promise is enigmatic and must be handled with care, for too often it has been inappropriately used in a manner that actually compares the works of Jesus with the works of believers, pitting them against one another. The clear emphasis of the pericope thus far has been the cooperation and unity first between the Father and the Son and now between the Son and believers. To impose at this juncture a point of comparison would be to misunderstand the statement in a very clear context. Whatever is greater about the works of believers, it is not in spite of Christ but because of him—belief “in me.”

The meaning of “greater works” is provided by the statement that immediately follows: “Because I am going to the Father” (ὅτι ἐγὼ πρὸς τὸν πατέρα πορεύομαι). Jesus has already spoken of his departure (cf. 13:31–38), which is the deliberate inauguration of the new mode of existence for the believers, the moment in which the believers themselves are transformed in Jesus by the Spirit (see comments on 13:33). Thus, by specifically mentioning his departure here, Jesus does not in any way separate himself from these “greater works.” In fact, as the immediate context has dictated, it is only in him and through him that these works find their source and power. Thus the comparison was never between the works of Jesus and the works of the disciples, but between the preglorification works of Jesus and the postglorification works of Jesus, with the disciples simply participating in the works of the risen and exalted Lord.

This interpretation is assisted by an earlier statement in the Gospel in which the Father, who is already working through the Son, will show him “works greater than these” (see comments on 5:20; cf. 1:50; 5:22–27). These “greater works” are connected to the time when Jesus is established and ruling as “the Son of Man”—note the comment made to Nathaniel in 1:50: “You shall see greater things than these” (emphasis added).43 The reader should note the remarkable promise made here. They are invited—no, commissioned (cf. Matt 28:18–20)—to participate in the ongoing and powerful ministry of God the Father, the exalted Christ, and the indwelling Holy Spirit. The ministry of the church is truly the work of God in the world.44

14:13 “And whatever you ask in my name I will do this, so that the Father may be glorified in the Son” (καὶ ὅ τι ἂν αἰτήσητε ἐν τῷ ὀνόματί μου τοῦτο ποιήσω, ἵνα δοξασθῇ ὁ πατὴρ ἐν τῷ υἱῷ). The necessary connection between Jesus and the disciples in v. 12 is just as necessary here. Jesus continues to describe the “greater works” of believers by describing in more detail the outworking of the power of life and ministry in the era of the exalted Christ. The phrase “whatever you ask in my name” (ὅ τι ἂν αἰτήσητε ἐν τῷ ὀνόματί μου), like the “greater works” statement discussed above, is wrongly interpreted if disassociated from Jesus, as if the one “praying” is the source and the primary agent giving direction and Jesus is the mere resource or supplier and the secondary, dependent agent. Rather, the statement makes two things explicit.

First, the believer is the one doing the “asking,” that is, placing himself beneath the primary agency of God. In this sense, the disciple is praying as a “representative” of Jesus,45 seeking to do what he would be doing if he were present—no, what he is doing in and through his disciples by means of his exalted presence through the Spirit, in the same way that the Father is working in and through Jesus (v. 10).

Second, the believer is asking “in my name” (ἐν τῷ ὀνόματί μου), that is, by means of the authority that resides and belongs to Jesus alone. Just as the Father has given authority to the Son, so the disciples of Jesus work not by means of their own authority but under the authority of the Son (see 1:12; 5:27). Since the concept of a “name” in the ancient world is the character of a person (see comments on 1:12), by asking in the name of Jesus the disciples are seeking not themselves but Christ, and their “prayer is to be in accordance with all that that name stands for.”46 In fact, one might say that to ask in the name of Jesus is to deny one’s own person and adopt the character of another person—in this case, the Son of God. Thus, such prayer is not done independent of God but is rooted in the power of God and the desires of God, which God will direct through us by his Spirit (cf. 16:13).

This participation of the believer in the life and ministry of the exalted Christ is for one overriding purpose: “So that the Father may be glorified in the Son” (ἵνα δοξασθῇ ὁ πατὴρ ἐν τῷ υἱῷ). Just as the work of the Father is inextricably intertwined with the Son, so also is the “glory” which is for the Father and in the Son; the glory is innate to their unity in relation to the godhead but different in relation to their distinct persons.47 “Glory” means “honor as enhancement or recognition of status or performance.”48 It is the opposite of self-effacement and humility. The identity of the believer—the disciple—is minimized, whereas the identity of God is magnified.

14:14 “If you ask me anything in my name I will do it” (ἐάν τι αἰτήσητέ με ἐν τῷ ὀνόματί μου ἐγὼ ποιήσω). Jesus ends this pericope with a final statement that is intended to make certain or to guarantee the future works of the believers.49 The prayers of God’s workers are not just placed before him and not just asked in Jesus’s name but are also, for all intents and purposes, already accomplished in the providential will of God. By this final statement Jesus holds himself accountable for the works of his disciples—that is how interconnected God is to the works of his disciples.

Theology in Application

In the second of eight sections of the farewell discourse, Jesus makes the first of six statements that explain, encourage, and exhort the disciples as they transition to the era of the new covenant, from life with Jesus to life “in Christ.” Through this pericope the reader is exhorted to replace their fear with faith in Jesus, who is the work of God in the world, the one who not only enacts but is the way, the truth, and the life.

Faith not Fear

The very first thing Jesus addresses with his disciples in the discourse proper is their fear (v. 1). He commands their fear away, providing the Father and the Son as the more appropriate object of their focus and devotion. The same powerful and authoritative voice that spoke creation into existence now addresses his disciples. Jesus calls them to faith, not fear. But note that this replacement is only possible because Christ has taken our fear upon himself. The only comfort a person can receive is the one that comes from the cross. The reader, no less than the disciples, is to receive and respond to the same, ongoing admonition today to live by faith not fear.

Our Father’s House

Heaven is a place (or at least a topic) that still fits comfortably in most of modern culture. Those with minimal religious interest will use the term as a concept for the afterlife, a happy place of peaceful dwelling for those who have died. In this pericope, however, the place about which Jesus speaks is entirely different. It is not a generic place beyond this one but a home, the very home of God the Father and the Son, who not only dwells there but prepares it for the children of God. This “house” belongs to God and to those—only those—who believe in the Son. For this reason it is a glorious place, not because of us but because of God; it is a home God prepared for us, a home in which we may be with God. This is a cosmological home, the extension of God’s grace from this temporal place into eternity.

The danger is that such common talk about a very uncommon thing will secularize it—transfer it from sacred to civil possession, making the dwelling of God a common depiction in cartoons, movies, and common speech—places in which it does not fit or make sense. No, the place about which Jesus speaks is “my Father’s house.” So we must speak of it as sacred, since God himself not only prepared it with his own hands but paid our debt fully in order to give us access to it. This place, therefore, cannot be secularized, for it is not a common possession. It is a place of grace, the holy of holies, the new creation, our true home. The church needs to recover this sacred place, not only as a future place but as a present hope that guides and directs the manner of our current dwelling.

The Blessing and Burden of John 14:6

Jesus is everything! As the way-truth-life, Jesus is the mode-reality-source of all things for all people. Jesus is the totality of what God has done, is doing, and will do; there is nothing of value in existence that does not come from or move toward Jesus Christ. This is the blessing, the promise of hope for those who believe in Jesus.

The antithesis of this blessing is a corresponding burden. Since Jesus is everything, those who do not have him have nothing. There is no middle ground or position. If this appears exclusive, it is; otherwise Christ would be excluded—and this cannot be! For too long the so-called problem of Christian exclusivism has placed humanity at the center. This is devastating not only to humanity but also to Christ. Christian grace is not an easy grace but an impossible grace which Christ has mediated to us by his person and work. If it is exclusive, it is because it is his alone to give. For this reason it can be inclusive, not without Christ but through him—but him alone, since it remains an impossible grace. The Gospel of John is inclusive in that it wants everyone to believe (20:31), but it is simultaneously exclusive in that it knows that this belief must be mediated through Christ. Jesus is the perfect combination of exclusivity and inclusivity, making impossible grace accessible to every possible person.

The Works of God

This pericope makes an important connection between the work of Christ and the work of the Father (v. 10). Without denying the need to distinguish them based upon an appropriate understanding of the doctrine of the Trinity, the Father and the Son are inseparable in their expression through the work of the Son. But there is more. The “work” of God is also inseparable from the “work” to be done by Christians (v. 12)—and this is the way it is supposed to be, for Jesus’s departure is in fact an intentional continuation of the same work of God. As we discussed above, Jesus magnifies the work to come (i.e., they are “greater works”) because the works to come, those that include those who believe, are the works of the risen and exalted Lord in the new era of the new covenant.

O church, you are participating in the power of the risen and exalted Lord and the works of God. You are called to facilitate the work of the kingdom of God, bestowing the blessings of God to the nations by the empowering Spirit of God. You have been commissioned by God to do the work of God in the world. Be faithful!

Christian Prayer

Prayer is not best described as accessing God but as being accessed by God. It is not about power but about submission. It is not about requesting but about submitting. Because the work of God never ceases to be his work, our access to the work of God, as real and effective as it is, is also always secondary. It is significant that the first thing Jesus discusses after articulating the Christian’s work of God is prayer (vv. 13–14). Prayer may be described as the primary mode of the Christian and their participation in the work of God. That is why the apostle Paul can command that prayer never cease (1 Thess 5:17), for it is both the expression of Christian work and the metaphor for that work. It is passive submission to God in the person of Christ and active service for God in the mission of God. Prayer therefore is the lifeblood of Christian existence, even human existence, and the most properly basic Christian activity.