Chapter 38

John 18:13–27

Literary Context

This pericope continues to depict the events surrounding the sacrificial death of the Son of God. After the surrender of Jesus, he is arrested, bound, and placed before the Jewish authorities for questioning. This makeshift Jewish trial had already been long decided; this was mere formality. But the Gospel’s interest is less on the Jewish authorities and their legal procedures and more on the witness of Christ and the witness of his disciple Peter when they are both confronted by the temple authorities. The narrative intentionally contrasts Christ with two significant characters in this pericope: the so-called Jewish high priest and the denial of Peter. The reader is directed to see more fully the nature of Jesus’s person and work as the High Priest (cf. Heb 4:14) and the true foundation of Christian discipleship and is exhorted to serve as a faithful witness to Christ in the world.

- VIII. The Crucifixion (18:1–19:42)

- A. The Arrest of Jesus (18:1–12)

- B. The Jewish Trial and Its Witnesses (18:13–27)

- C. The Roman Trial before Pilate (18:28–40)

- D. The Verdict: “Crucify Him!” (19:1–16)

- E. The Crucifixion of Jesus (19:17–27)

- F. The Death and Burial of Jesus (19:28–42)

Main Idea

Jesus is the true high priest, the foundation of Christian discipleship, and the motivating source of the church’s witness to the world.

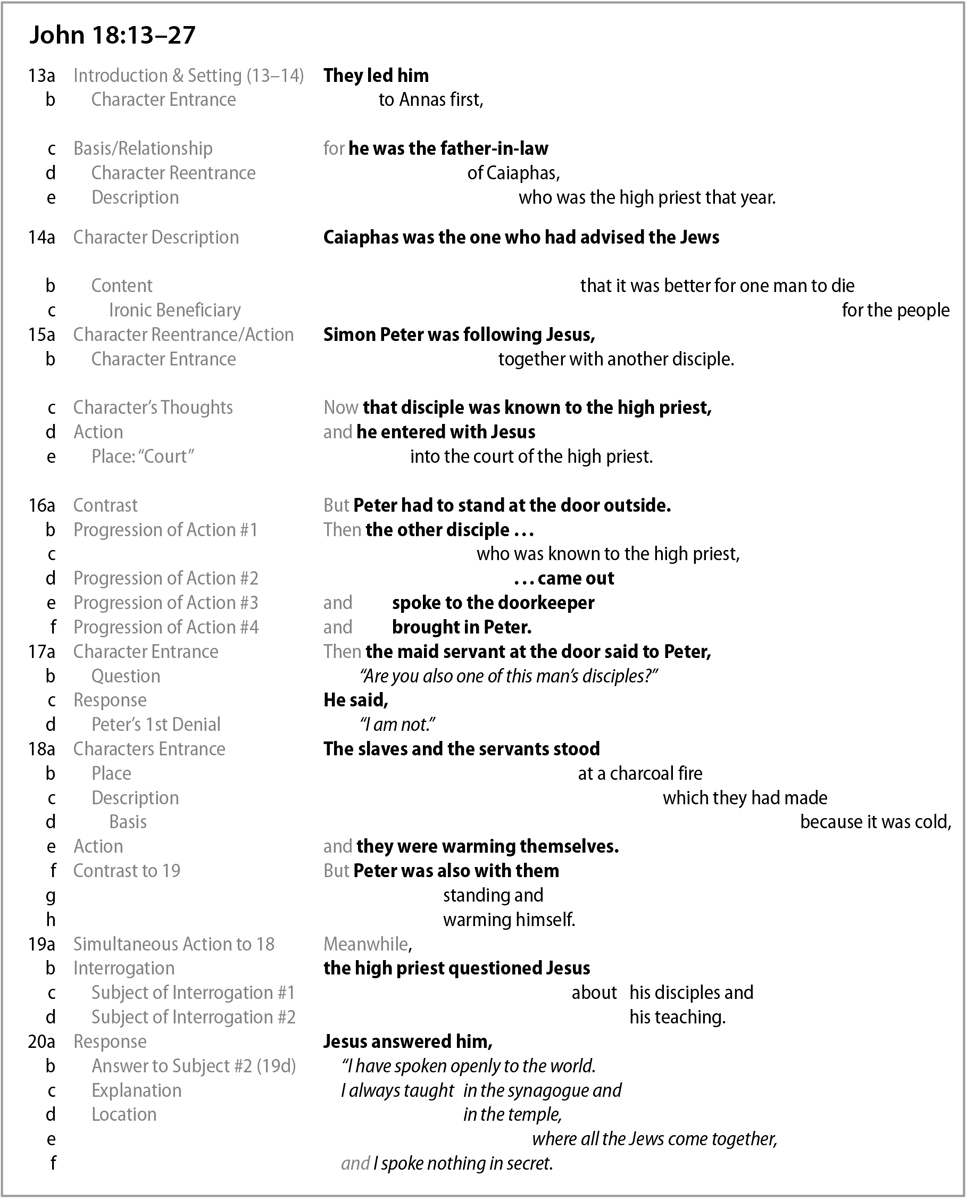

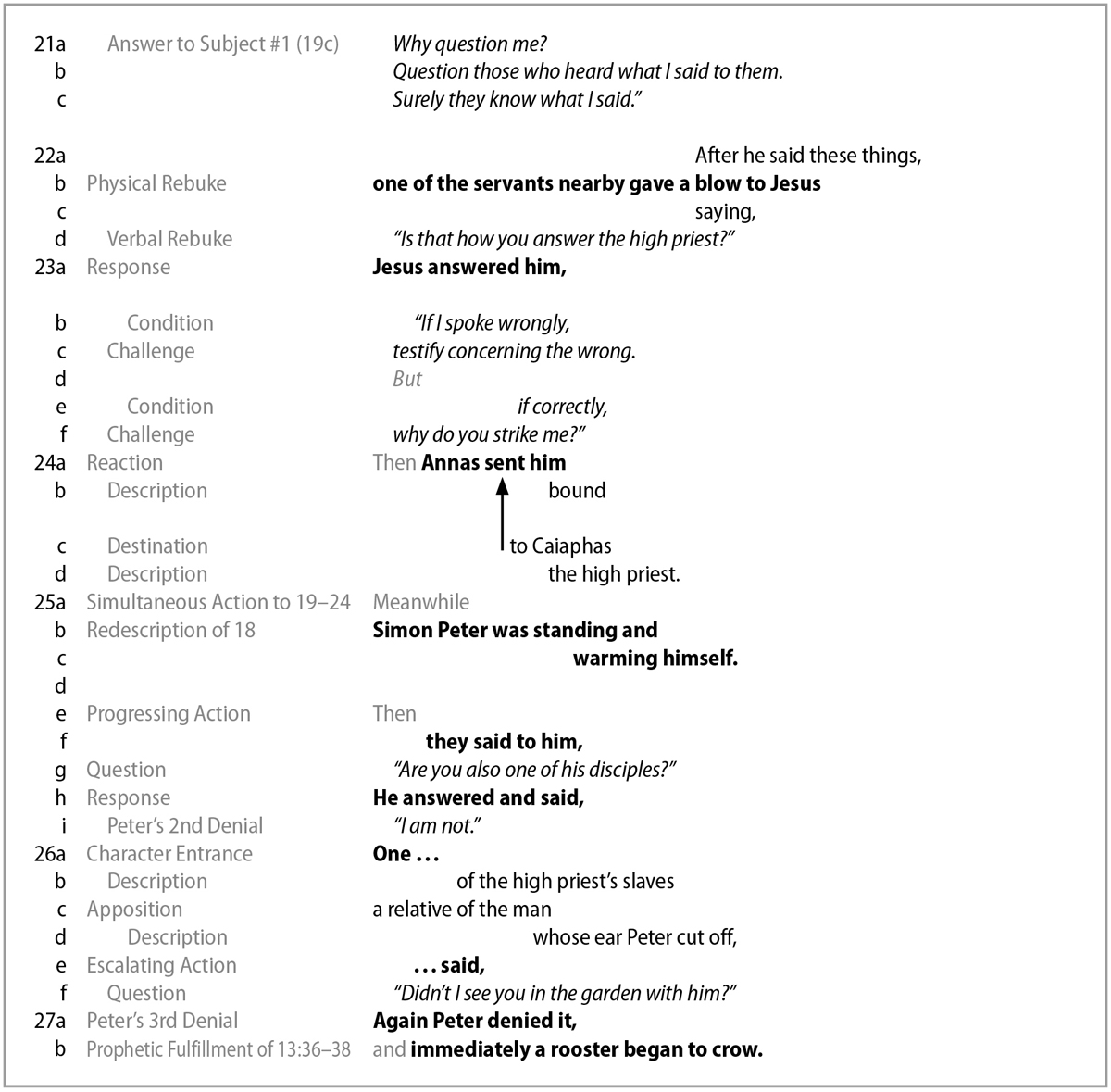

Translation

Structure and Literary Form

The structure of this pericope is different than the basic story form (see Introduction). The structure is guided by the trial motif that defines the pericopae leading up to the crucifixion: the Jewish trial (18:13–27), the Roman trial (18:28–40), and the verdict (19:1–16). This pericope contains a brief introduction (vv. 13–14) followed by an intercalation, a rhetorical technique that encloses or “sandwiches” one scene in the middle of a different scene (forming an A1–B–A2 pattern), so that each scene affects the interpretation of the other. The framing scene and the framed (embedded) scene are placed on par with each other, with neither having either logical or chronological priority. Either scene (the framing or the framed) may comment on the other by way of comparison or contrast.1 Fowler describes their function and relation well: “Intercalation is narrative sleight of hand, a crafty manipulation of the discourse level that creates the illusion that two episodes are taking place simultaneously. In an intercalation neither episode has begun until both have begun, and neither is concluded until both are concluded.”2 By means of the intercalation, the reader is expected to hear the denial of Peter at the very moment Jesus is placing his reputation on Peter’s witness.

Exegetical Outline

- B. The Jewish Trial and Its Witnesses (18:13–27)

- 1. Jesus Delivered to the Jewish Authorities (vv. 13–14)

- 2. The First Denial of Peter (vv. 15–18)

- 3. The Witness of Christ and His Disciples (vv. 19–24)

- 4. The Second and Third Denials of Peter (vv. 25–27)

Explanation of the Text

When one examines the Fourth Gospel, it becomes immediately apparent that the historical details of this pericope are both sparse and confusing, especially in regard to Jewish legal proceedings. Before we analyze the narrative details, we must address the following question: Is this an official trial? A full-scale Jewish trial would have been performed by the Sanhedrin, the Jewish ruling council, as depicted in the Synoptics (see Mark 14:53). This “trial” is not described as occurring before the Sanhedrin but seems to have involved select members of Jerusalem’s municipal aristocracy in collaboration with the high priest, probably in order to keep peace between Rome and the people.3 This is technically more than an interrogation, however, for this trial is clearly driven by political concerns (11:48), not just religious concerns (cf. Mark 14:64). There is no reason to doubt the historicity of the Gospel’s account or to challenge the Gospel’s depiction of Jewish trials.

18:13 They led him to Annas first, for he was the father-in-law of Caiaphas, who was the high priest that year (καὶ ἤγαγον πρὸς Ἅνναν πρῶτον· ἦν γὰρ πενθερὸς τοῦ Καϊάφα, ὃς ἦν ἀρχιερεὺς τοῦ ἐνιαυτοῦ ἐκείνου). The first section of the pericope (vv. 13–14) serves to introduce the reader to the context and characters involved in the Jewish trial of Jesus. These verses have raised confusion regarding the role of Annas and the identity of the “high priest” in v. 19. Because of its importance for the entire pericope, we will address the identity of the high priest here. If Caiaphas was the current high priest, why was Jesus not led before him instead of Annas? And is the high priest who interrogates Jesus in v. 19 Annas or Caiaphas?

The answers to these questions are partially resolved by explaining the identity of Annas and the nature of the high priesthood in first-century Judaism. Annas had been high priest from AD 6–15 (Josephus, Ant. 18.26–35) and was succeeded not only by his son-in-law, Caiaphas, but also by all five of his sons (Josephus, Ant. 20.198). Annas was therefore “the patriarch of a high priestly family,”4 and may have been considered as the “highest” or most influential of the high priests, since the biblical tradition depicted the office of the high priest as lifelong, and it was customary to refer to the entire high-priestly family as “high priests.”5 The narrator is not attempting to be intentionally cryptic here but is simply describing two hearings. The “first” (πρῶτον) with Annas is designated as such, although no record of the hearing is provided, and the second is with Caiaphas, whom the narrator is careful to describe as the high priest “that year” (τοῦ ἐνιαυτοῦ ἐκείνου) or, more simply, “at that time.”

Since Caiaphas is the current high priest, it would seem that he is the one who interrogates Jesus beginning in v. 19, the one clearly introduced by the narrator as “the high priest.” This is even supported by v. 14, which focuses the reader’s attention directly on Caiaphas by reminding the reader of his identity and already important role in the narrative. Yet in v. 24 the narrator explains that after the interrogation with the “high priest,” who would logically be Caiaphas, Annas had him sent to Caiaphas. The common divide between interpreters regarding the identity of the interrogator in this scene is often based upon which verse is given priority: if v. 19, then the interrogator is logically Caiaphas; if v. 24, then the interrogator must be Annas. The argument by this commentator is that this cryptic depiction of the “high priest” bears the marks of intentionality by the narrator, who is directing the reader to see that in this trial neither Annas nor Caiaphas were properly functioning as the high priest, for only Jesus was able to fulfill the requirements of that office.6

This judgment regarding the intentionality of the narrative is directed by its own movement and is sensitive to the narrative’s bent. Until v. 24 there would be every reason to think the “high priest” interrogating Jesus was Caiaphas, for the text had just stated that Caiaphas was the high priest that year.7 Said another way, only Caiaphas is known as the high priest from the text itself; Annas is simply described by his relation (by marriage) to Caiaphas. Only by using other first-century sources do we know that Annas was also a high priest and likely the high-priestly patriarch. Yet v. 24 causes the reader to turn back and reexamine the previous verses with fresh eyes, intentionally forcing a swirl of confusion that demands the reader to ask whether the one doing the questioning the whole time was not Caiaphas but Annas, who is only now sending Jesus on to the current high priest. That is, the text forces the reader to ask the question: Who is the high priest? This is no “victimization” of the reader, as suggested by Staley, making the reader “an outsider through his construal of the preceding scene.”8 In contrast, by using this narrative strategy, the rhetorical intention of the narrator is to make the reader “an insider” by allowing the narrative’s swirling depiction of the high priest to implicitly portray the ironic confusion between the historical characters, thereby magnifying the cosmological characterization of Jesus that has been developing throughout the Gospel.

This is not to deny that a real high priest (or more likely two of them in turn; cf. Luke 3:2) actually interrogated Jesus. Rather, it is to say that the narrative is more interested in projecting Jesus in his high-priestly actions than it is to chronicle the high priests of first-century Judaism. As the Gospel has done elsewhere before (see comments on 2:10 and 3:1), the narrative has played the historical characters against themselves to establish upfront for the reader the fuller context of the scene about to unfold and the true identity of Jesus.

18:14 Caiaphas was the one who had advised the Jews that it was better for one man to die for the people (ἦν δὲ Καϊάφας ὁ συμβουλεύσας τοῖς Ἰουδαίοις ὅτι συμφέρει ἕνα ἄνθρωπον ἀποθανεῖν ὑπὲρ τοῦ λαοῦ). The introduction to the pericope (vv. 13–14) concludes with a brief reintroduction of Caiaphas, preparing the reader for his (apparent) interrogation of Jesus in vv. 19–24. Caiaphas was first introduced to the reader near the end of Jesus’s public ministry (see comments on 11:49). His importance is not merely his position of authority but the manner in which he used it to direct the strategy of the Jews to kill Jesus (see 11:50–52), which the narrator intentionally reminds the reader. By this introduction the reader is not only reminded of the political maneuvering of Caiaphas and the Jewish authorities but of the cosmological maneuvering of God so that the decision of Caiaphas was and continues to be facilitated by the preordained will of God (see comments on 11:53).

18:15 Simon Peter was following Jesus, together with another disciple. Now that disciple was known to the high priest, and he entered with Jesus into the court of the high priest (Ἠκολούθει δὲ τῷ Ἰησοῦ Σίμων Πέτρος καὶ ἄλλος μαθητής. ὁ δὲ μαθητὴς ἐκεῖνος ἦν γνωστὸς τῷ ἀρχιερεῖ, καὶ συνεισῆλθεν τῷ Ἰησοῦ εἰς τὴν αὐλὴν τοῦ ἀρχιερέως). The second section of the pericope (vv. 15–18) transitions to Simon Peter who is described as “following” (Ἠκολούθει) Jesus, almost certainly from the garden where he was arrested by the Jewish and Roman authorities. No reason is given for his pursuit of Jesus; the narrator focuses less on what he is thinking and more on what he is about to do. After being rebuked by Jesus, his actions do suggest continued allegiance—an allegiance that is about to be challenged. It is important to note that this section is the first of three sections that perform an intercalation, a rhetorical technique that encloses or “sandwiches” one scene in the middle of a different scene (forming an A1–B–A2 pattern), so that each scene affects the interpretation of the other (see comments before v. 13). This section (vv. 15–18) is the first of the framing sections (A1). Our interpretation must read the entire intercalation as interrelated, forming a cumulative whole that provides a unified message.

Although the narrator clearly focuses on Peter (denoted by the singular verb), a second character is also mentioned as being present with Peter—“another disciple” (ἄλλος μαθητής). This is not the first time an anonymous disciple has been mentioned (see comments on 1:40), and although a specific name or title is not given here, many scholars think this disciple is to be identified with “the Beloved Disciple,” who was officially introduced in the farewell discourse and appears throughout the end of the Gospel (19:25–27, 35; 20:1–10; 21:1–7, 20–24; for an overview of the “Beloved Disciple,” see comments on 13:23). As discussed previously, anonymity is itself a narrative tool to develop both plot and characterization. The challenge is to interpret the “gap that anonymity denotes” with a precision that is shaped by the narrative as a whole.9

In this pericope the anonymous disciple is in a position that signals a privileged relationship to the high priest; according to the narrator he “was known to the high priest” (ἦν γνωστὸς τῷ ἀρχιερεῖ), thus providing him entrance into the high priest’s court. The details of this anonymous disciple’s relationship are not given and therefore are secondary to the narrative depiction.10 What is given is the fact of his relation, a relation that gives him special access to the events surrounding Jesus. Whether or not they can be equated, this “anonymous disciple” has a privileged relationship with the high priest in a manner similar to the Beloved Disciple’s privileged relation to Jesus (see 13:23). Moreover, like the Beloved Disciple this “disciple” is also in a unique relationship with Peter (see 13:24), who is frequently depicted by the Gospel to be in relationship with the Beloved Disciple. And according to the narrator, this disciple is also in relation to Jesus, with whom “he entered” (συνεισῆλθεν) into the court of the high priest.11

18:16 But Peter had to stand at the door outside. Then the other disciple, who was known to the high priest, came out and spoke to the doorkeeper and brought in Peter (ὁ δὲ Πέτρος εἱστήκει πρὸς τῇ θύρᾳ ἔξω. ἐξῆλθεν οὖν ὁ μαθητὴς ὁ ἄλλος ὁ γνωστὸς τοῦ ἀρχιερέως καὶ εἶπεν τῇ θυρωρῷ καὶ εἰσήγαγεν τὸν Πέτρον). The contrast between the “anonymous disciple” and Peter is made clear by the narrator, for while that “disciple” is on the inside with Jesus (v. 15), Peter is on the “outside” (ἔξω). The inside-outside language serves a larger, more metaphorical role, defining these two disciples by means of their geographic relation to Jesus. The “other disciple,” who is again depicted by his connection to the high priest, speaks to “the doorkeeper” (τῇ θυρωρῷ), a female (denoted by the gender of the noun), who then gives this disciple permission to bring Peter into the court. The secondary role of Peter is impossible to miss. The detailed description of these two disciples—the anonymous disciple/Beloved Disciple12 and Peter—serves as a frame for the entire events surrounding the crucifixion of Jesus. From the arrest and trial (v. 15–16) to the morning of Jesus’s resurrection (20:2–8), these two disciples serve as direct eyewitnesses and respondents to the climactic work of the Son (see comments on 13:23).

18:17 Then the maidservant at the door said to Peter, “Are you also one of this man’s disciples?” He said, “I am not” (λέγει οὖν τῷ Πέτρῳ ἡ παιδίσκη ἡ θυρωρός, Μὴ καὶ σὺ ἐκ τῶν μαθητῶν εἶ τοῦ ἀνθρώπου τούτου; λέγει ἐκεῖνος, Οὐκ εἰμί). The female doorkeeper, here qualified as “the maidservant at the door” (ἡ παιδίσκη ἡ θυρωρός), is a slave girl assigned to the entrance so as to be aware of who entered and exited the premises and to take notice of visitors, permitting entrance only to those who belonged.13 The phrase “this man” (τοῦ ἀνθρώπου τούτου) probably expresses scorn, not pity.14 The form of the negation, “not” (Μὴ), causes some to think the question expects a negative answer and is therefore accusatory.15 Others suggest that the addition of “you also” (καὶ σὺ) changes the question to expect a positive answer and implies that Peter might be a disciple “in addition to” the anonymous disciple.16 In this context the question simply assumes that Jesus had many disciples and asks if Peter was also one of them.17 She is the doorkeeper and is making herself aware of the reason for a visitor’s entrance.

The focus of this verse, however, is not on the question of the maidservant but on the answer of Peter. In contrast to the Baptist (see 1:20–21), the “I am not” of Peter is a self-focused response, a witness against himself. Although the text does not give the reason for his response, whether it was for protection from harm or embarrassment, Peter was certainly not afraid to deny Christ. He chose instead to fear the question of a maidservant assigned to watch the door: “The voice of a mere woman terrified Peter.”18 In one sense Peter was on the inside, having been given special access to the court of the high priest. Yet when asked about the true High Priest, the one to whom he had also (and more astoundingly) been given access, Peter acts like an outsider, which the next verse makes dramatically clear.

18:18 The slaves and the servants stood at a charcoal fire which they had made because it was cold, and they were warming themselves. But Peter was also with them standing and warming himself (εἱστήκεισαν δὲ οἱ δοῦλοι καὶ οἱ ὑπηρέται ἀνθρακιὰν πεποιηκότες, ὅτι ψῦχος ἦν, καὶ ἐθερμαίνοντο· ἦν δὲ καὶ ὁ Πέτρος μετ’ αὐτῶν ἑστὼς καὶ θερμαινόμενος). The second section of the pericope (vv. 15–18) concludes by portraying the outsider status of Peter in a manner that speaks without words. The “impressions” created by the image recounted by the narrator serves as commentary on the words he had just spoken. All the opponents of Jesus were gathered in one place, not only the religious officials (e.g., Annas, Caiaphas) but also “the slaves” (οἱ δοῦλοι), domestic servants of the high priest and temple like the maidservant, and “the servants” (οἱ ὑπηρέται), the “assistants” of the Jewish authorities sent to arrest Jesus (see comments on 18:3). And among them was Peter, warming himself by the fire—an image that is intended to express communion, fellowship, even intimacy; it is an ironic fellowship since just moments before he was attacking the same servants (see 18:10–11)!19 Peter was standing “with them” (μετ’ αὐτῶν) and sharing in their warmth and comfort at the same moment (based upon the intercalation) that Jesus (his Lord!) was being treated like an outsider and physically abused.20 Peter’s first witness to Christ was an anti-witness, a denial. But Jesus is not done with Peter; by the Gospel’s end he will be warming himself at another “charcoal fire” (see 21:9).21

18:19 Meanwhile, the high priest questioned Jesus about his disciples and his teaching (Ὁ οὖν ἀρχιερεὺς ἠρώτησεν τὸν Ἰησοῦν περὶ τῶν μαθητῶν αὐτοῦ καὶ περὶ τῆς διδαχῆς αὐτοῦ). The word translated as “meanwhile” (οὖν) is generally a “marker of continuation of a narrative” (e.g., “then,” “so,” “now”),22 but in the context of an intercalation in which the two episodes are taking place simultaneously (see comments before v. 13), the word transitions from one scene to the next in a temporally overlapping manner. As we have already discussed, the narrator’s depiction of the high priest’s questioning of Jesus is mysterious when read in light of v. 24 and is intentionally crafted so as to depict neither Caiaphas or Annas as the high priest but rather the one they have arrested and bound, Jesus (see comments on v. 13). Nothing in this “trial” looks official, for this interrogation functions more like a preparatory verdict than a legitimate legal procedure. This “trial” seems less like a proceeding that determines shameful behavior and more like an opportunity to deliver shame. The subject matter of this interrogation is quite general; the high priest questions Jesus about his disciples and his teaching. Particulars are not in view here; this court is evaluating the entire person and work of Jesus.23

18:20 Jesus answered him, “I have spoken openly to the world. I always taught in the synagogue and in the temple, where all the Jews come together, and I spoke nothing in secret” (ἀπεκρίθη αὐτῷ Ἰησοῦς, Ἐγὼ παρρησίᾳ λελάληκα τῷ κόσμῳ· ἐγὼ πάντοτε ἐδίδαξα ἐν συναγωγῇ καὶ ἐν τῷ ἱερῷ, ὅπου πάντες οἱ Ἰουδαῖοι συνέρχονται, καὶ ἐν κρυπτῷ ἐλάλησα οὐδέν). The narrator may have started his account by describing what the high priest asked of Jesus, but Jesus is the one who speaks first, befitting the narrative’s desire to portray Jesus as the functioning (and rightful) high priest in this scene. Jesus addresses the first of the two issues raised by the high priest: his teaching. Jesus states emphatically, “I have spoken openly to the world” (Ἐγὼ παρρησίᾳ λελάληκα τῷ κόσμῳ). The term “openly” (παρρησίᾳ) has been previously used to refer to speaking “in public” (e.g., 7:4, 26; 11:54) and “plainly” or “clearly” (e.g., 10:24; 11:14; 16:25, 29) and is used here to suggest that Jesus has not hidden or distorted his message or his intentions but has shared them openly (“to the world”). The use of “world” here could seem hyperbolic to the questioning high priest, but actually perfectly describes Jesus’s intended audience according to the prologue (see 1:10). Jesus explains further that he has done his teaching in the synagogue (cf. 6:59) and the temple (cf. 5:14; 7:14, 28; 8:20; 10:23), the places Jews would be expected to assemble. This serves as evidence that his teaching ministry was anything but secretive.

18:21 “Why question me? Question those who heard what I said to them. Surely they know what I said” (τί με ἐρωτᾷς; ἐρώτησον τοὺς ἀκηκοότας τί ἐλάλησα αὐτοῖς· ἴδε οὗτοι οἴδασιν ἃ εἶπον ἐγώ). Jesus then addresses the second of the two issues raised by the high priest: his disciples—though in a manner that connects his disciples to his teachings. Since the message of Jesus was intended to result ultimately in the salvation of the world, the true test of the intentions and validity of Jesus’s teaching can be witnessed by the fidelity of his disciples.24 The person and work of Jesus had never been a free-floating abstraction but was a “Word-become-flesh” (1:14) and a message that resulted in the creation of the Father’s children (1:12). This is not to suggest that Christ’s work can be fully equated with the church but to say that the work of Christ can be witnessed in the existence and therefore the life of the church. It is not insignificant that God through the apostle Paul declares the church to be “the body of Christ” (e.g., 1 Cor 12:27). Just as Jesus is the Word-become-flesh, so the church is the flesh-become-word—declaring the grace, truth, and love of the Father which they received from the Son (and by the Holy Spirit).

Jesus does not respond at all like an accused person at an interrogation, especially in comparison to the submissive and penitent behavior recorded of others who appeared before municipal authorities (see Josephus, Ant. 14.172–73).25 Jesus’s response to the high priest is challenging (“Why question me?”) and directive (“Question those. . .”). As we discussed above, in this scene Jesus functions as the (true) high priest, reversing the authoritative controls and throwing the interrogation back upon his interrogators.

This section is the center section (B) of the intercalation (see comments before v. 13), which means that at the very moment Peter was denying Jesus while sharing in the warmth and fellowship of the temple servants, just some distance away stood Jesus with hands bound inside a chamber with the high priest, claiming that his disciples were reliable witnesses to his teaching and therefore to his identity. The contrast is stark and is intended to penetrate the heart of the reader.

18:22 After he said these things, one of the servants nearby gave a blow to Jesus saying, “Is that how you answer the high priest?” (ταῦτα δὲ αὐτοῦ εἰπόντος εἷς παρεστηκὼς τῶν ὑπηρετῶν ἔδωκεν ῥάπισμα τῷ Ἰησοῦ εἰπών, Οὕτως ἀποκρίνῃ τῷ ἀρχιερεῖ;). An unnamed “servant” (ὑπηρετῶν), the same term used in the previous pericope for the assistants to the Jewish authorities sent to arrest Jesus (see comments on 18:3), responds to Jesus with a tangible expression of disapproval. The narrator explains that the servant gave “a blow” (ῥάπισμα) to Jesus. The term originally meant a blow with something like a rod, but it can also refer to a strike with an open hand, like a slap in the face.26 Commentators often discuss the illegality of such a physical response, but in light of the fact that the religious authorities have put God on trial, binding him and demanding that he answer their questions, the blow to the face of the Son of Man is hardly the greatest offense.

The irony, however, is not fully captured by the blow delivered to Jesus, for it is the words of the anonymous servant that more clearly depict the depth of misunderstanding. The reader knows full well that the question should be immediately reversed and asked of the servant: “Is that how you treat the true High Priest?” It is remarkable that this one question is the only statement any character representing the Jewish authorities and high priest makes in the pericope’s depiction of the questioning of Jesus. In this interrogation, Jesus asked the questions.

18:23 Jesus answered him, “If I spoke wrongly, testify concerning the wrong. But if correctly, why do you strike me?” (ἀπεκρίθη αὐτῷ Ἰησοῦς, Εἰ κακῶς ἐλάλησα, μαρτύρησον περὶ τοῦ κακοῦ· εἰ δὲ καλῶς, τί με δέρεις;). Jesus does not leave the falsely attributed abuse without commentary but offers what becomes the final statement of this interrogation. Jesus is not to be judged here as speaking without turning the other cheek. In this moment he speaks as the Judge and Authority (5:22–27), supported by all the authoritative witnesses that have been presented on his behalf, including not only his own works and John the Baptist but also the witnesses of the Father and Scripture (see 5:30–47). What Jesus’s response reveals is that the grace of God does not come without truth (1:17). The grace of God is evidenced by the very fact that he even received such questions at all, let alone that he allowed a servant to strike him in the face, and ultimately place him on the cross. The gospel is seen in that Jesus will respond in an equally physical manner to the blow of the Jews, not by giving it back to them but by placing the necessary and justified response upon himself.

18:24 Then Annas sent him bound to Caiaphas the high priest (ἀπέστειλεν οὖν αὐτὸν ὁ Ἅννας δεδεμένον πρὸς Καϊάφαν τὸν ἀρχιερέα). The third section of the pericope (vv. 19–24) concludes with a final comment by the narrator that dramatizes the intentionally ironic depiction of the binding and interrogation of Jesus. As we discussed above (see v. 13), up to this point the reader was logically thinking that the “high priest” was the one introduced as such, Caiaphas. This verse intentionally obscures that assumption in a manner that forces the reader to ask the question: Who is the high priest? After watching the narrative unfold, neither Annas nor Caiaphas qualify. Rather it is Jesus, the one bound, arrested, and under interrogation who alone qualifies, not merely because of this scene but because of what the reader has long been told about him (e.g., 5:22–27). The reader sees more clearly than ever how carefully the narrative’s plot depicts and explains the cosmological realities in, around, and through the unfolding of the historical events.

18:25 Meanwhile Simon Peter was standing and warming himself. Then they said to him, “Are you also one of his disciples?” He answered and said, “I am not” (Ἦν δὲ Σίμων Πέτρος ἑστὼς καὶ θερμαινόμενος. εἶπον οὖν αὐτῷ, Μὴ καὶ σὺ ἐκ τῶν μαθητῶν αὐτοῦ εἶ; ἠρνήσατο ἐκεῖνος καὶ εἶπεν, Οὐκ εἰμί). The fourth section of the Gospel (vv. 25–27) returns to Peter again, picking up where it had intentionally concluded before (vv. 15–18). This section is the final framing section (A2) of the intercalation (see comments before 18:13). This does not chronologically follow Jesus’s statement above (v. 22) but is narratively occurring at the exact same time.27 The reader is expected to feel the sharpness of the contrast as the text returns to the denial or anti-witness of Peter.

The narrator reminds the reader where Peter was so as to pick up the intercalation from v. 18, standing and warming himself with the very servants of the Jewish authorities who arrested Jesus. One of them asked Peter, now for the second time (cf. v. 17), if he was one of Jesus’s disciples. And Peter says “I am not” (Οὐκ εἰμί) for a second time, acting again as an outsider and anti-witness of Jesus. It is worth noting how none of the speakers are named, which suggests even further that anonymity is a rhetorical strategy of this pericope. The only people who are clearly identified before they speak are Jesus and Peter, for as we discussed above, even the high priest is not directly named before he speaks (see v. 19). In this way the text makes a dramatic and ironic presentation by means of the intercalation: at the same time the real high priest (Jesus) is not treated like one, the real witness (Peter) is not acting like one.

18:26 One of the high priest’s slaves, a relative of the man whose ear Peter cut off, said, “Didn’t I see you in the garden with him?” (λέγει εἷς ἐκ τῶν δούλων τοῦ ἀρχιερέως, συγγενὴς ὢν οὗ ἀπέκοψεν Πέτρος τὸ ὠτίον, Οὐκ ἐγώ σε εἶδον ἐν τῷ κήπῳ μετ’ αὐτοῦ;). The narrative concludes the intercalation between Peter and Jesus with the third and climactic denial by Peter. While the person asking the question is again anonymous, this time an important detail is provided. The questioner is a personal slave of the high priest and a “relative” (συγγενὴς) of Malchus, the man whose ear was cut off by Peter (see 18:10). This was no flippant question; it was more authoritative and personal than the first two. And this questioner personally witnessed Peter represent and defend Jesus in the garden.

18:27 Again Peter denied it, and immediately a rooster began to crow (πάλιν οὖν ἠρνήσατο Πέτρος· καὶ εὐθέως ἀλέκτωρ ἐφώνησεν). Peter’s denial need merely be summarized here, for the reader already knows the words Peter would use (cf. vv. 17, 25). After presenting Peter’s third and climactic denial of Jesus, the pericope concludes with another temporally overlapping incident, the crow of a rooster. Jesus had specifically foretold Peter that far from sacrificially offering his life on behalf of Jesus, he would deny him three times (see 13:36–38). And just as the intercalation between Peter and Jesus contrasted their simultaneously occurring responses to questions posed by the temple authorities, so also the moment Peter spoke the last of this threefold denial, “immediately” (εὐθέως) the voice of the rooster was heard. Jesus is not finished with Peter, as the reinstatement of Peter in the Gospel’s epilogue will show (21:15–23). The fact that the Gospel ends with Peter’s reinstatement suggests that this pericope’s depiction of his misunderstanding of Jesus’s person and work and his failure to witness to Jesus offers a significant perspective on the nature of Christian discipleship.

Theology in Application

This pericope offers an interpretive description of the Jewish trial of Jesus and a potent exhortation to the reader in regard to the identity of Jesus Christ and the identity of his disciples as witnesses in the world. Like the previous pericope (18:1–12), even while being arrested, bound, and questioned, Jesus is in complete control, dictating the terms and guiding his own interrogation. Through this pericope the reader is able to understand the gracious work of the true High Priest and is guided to wrestle with the challenge of Christian discipleship and being a witness for Christ.

The High Priest Who Was Not Treated like One

The rhetorical strategy of this account directs the reader to see Jesus as the legitimate or true High Priest by creating an ironic confusion between the historical characters that ultimately has them working against one another (see comments on v. 13). This narrative maneuver is not for the purpose of entertainment but to provide interpretive guidance to the entire Jewish trial. In this trial the one arrested and bound was (and had always been) in control, dictating the terms. Even his arrest, as the previous pericope explained (18:1–12), was more accurately an act of surrender, a sacrificial offering.

What makes the true high priest unique is that his own priestly expectations (and those from the Father) required that he be bound and arrested and eventually crucified. None of this required him to lose his position as the Judge (5:22–27); it simply required that his judgment and authority would direct the focus of the world’s hate (and even the wrath of God) upon himself. This high priest was not only offering the sacrifice, he was the sacrifice. This high priest was the perfect sacrifice, “the Lamb of God” (1:29). While this high priest was not treated like the high priest, he was certainly acting like one.

The Disciple Who Was Not Acting like One

Using the rhetorical technique of intercalation (see comments before v. 13), the narrative displayed the “interrogations” of Jesus and Peter in a manner that had them occurring simultaneously. At the very same moment Jesus was being denied by Peter, Jesus was claiming that his disciples were reliable witnesses to his teaching and therefore to his identity. The contrast is stark and is intended to penetrate the heart of the reader.

Peter exemplifies the paradox of Christian discipleship. Our spiritual life finds its source not in good intentions but in the Good Shepherd, who willingly gave himself for us. The denials of Peter depict with glaring detail how the creation of the children of God was never intended to be based upon the merit of the blood, flesh, or will of humanity but is “from God” alone (1:13). This does not deny what Jesus says to his questioners in v. 21, that the church is to be his witnesses. It is to say rather that our witness cannot stand on its own but can only be a response to what Christ has already done on our behalf. Christian discipleship is not best defined as a work or action done for God but as action done in response to God and his work.

The Church as the Witness of Christ

As much as discipleship is a response to what God has done, Jesus was serious when he said to his interrogators about his disciples that they “hear” and therefore “know what I said” (v. 21). Such a statement implies that Jesus’s disciples are suitable witnesses. This verse is one among many in the Gospel that teaches that the Christian is to be a participant in God’s mission to the world.

The witness of the church on behalf of Christ, however, springs not from adequacy but from inadequacy. It is only our “I am not” that allows us to say “I am.” Peter forgot what he said earlier in 6:68–69: “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life.” For this reason the Christian can answer forthrightly when asked about his association to Christ, “I am,” but only because he knows that he is the “I am not” and Jesus Christ alone is the “I AM.”