One

A CITY ON ROLLERS

SAN FRANCISCO’S EARLY HEYDAY

OF MOVING HOUSES

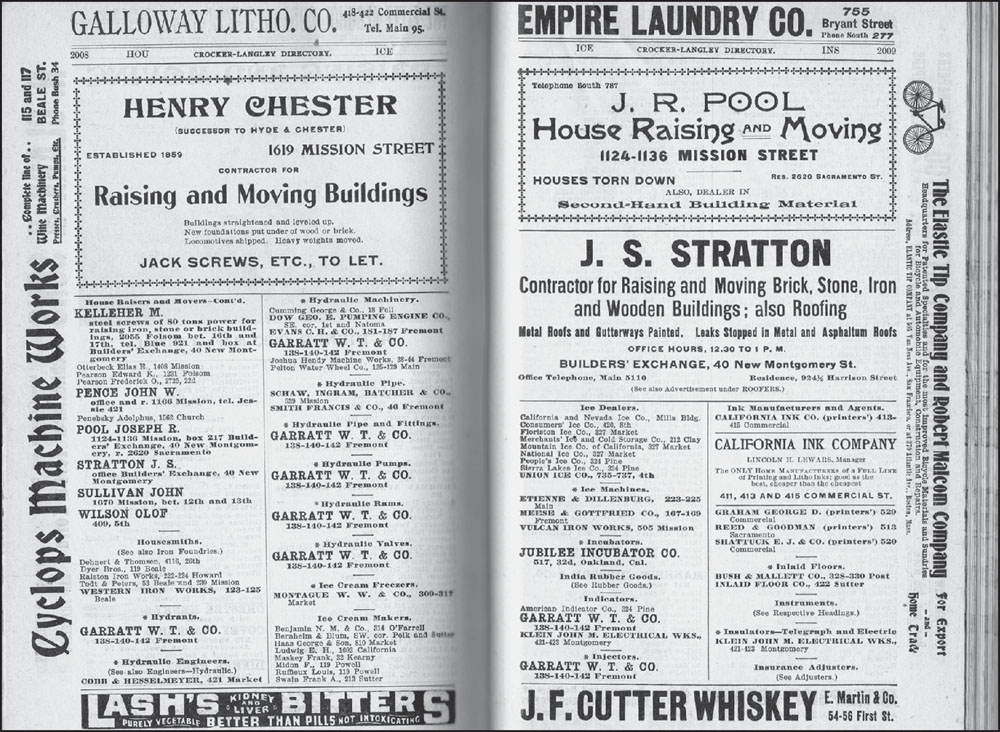

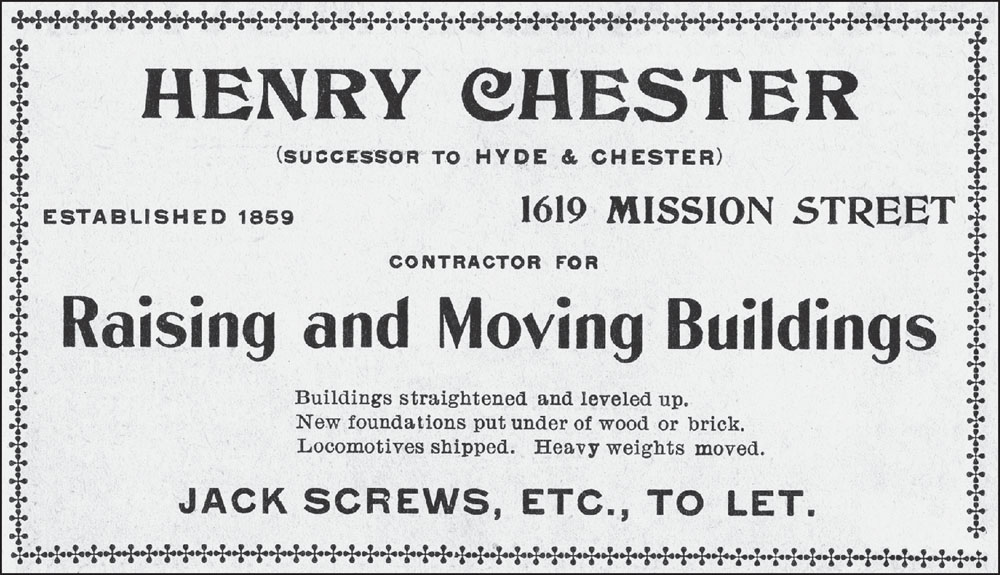

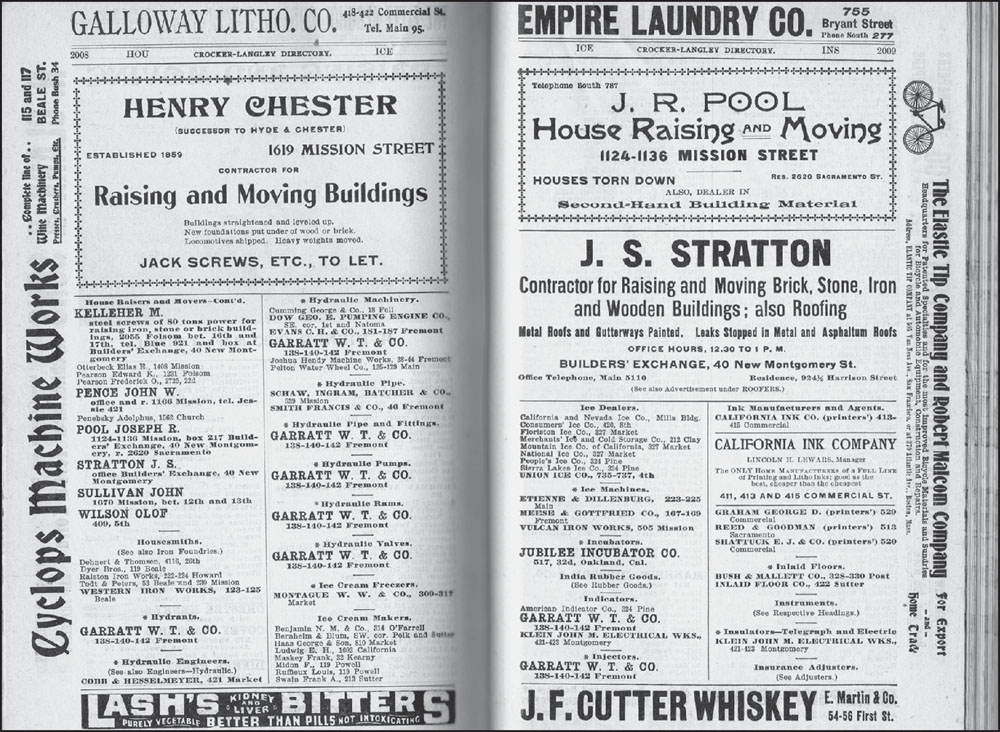

Advertisements and listings in the 1900 Pope-Langley San Francisco City Directory show just how competitive the business of moving houses was at the turn of the century, with over 19 of them appearing in this one edition alone. The house-moving industry blossomed as the city exploded in growth, and buildings were moved around like chessmen on a constantly changing board. (Courtesy of the Glenn D. Koch collection.)

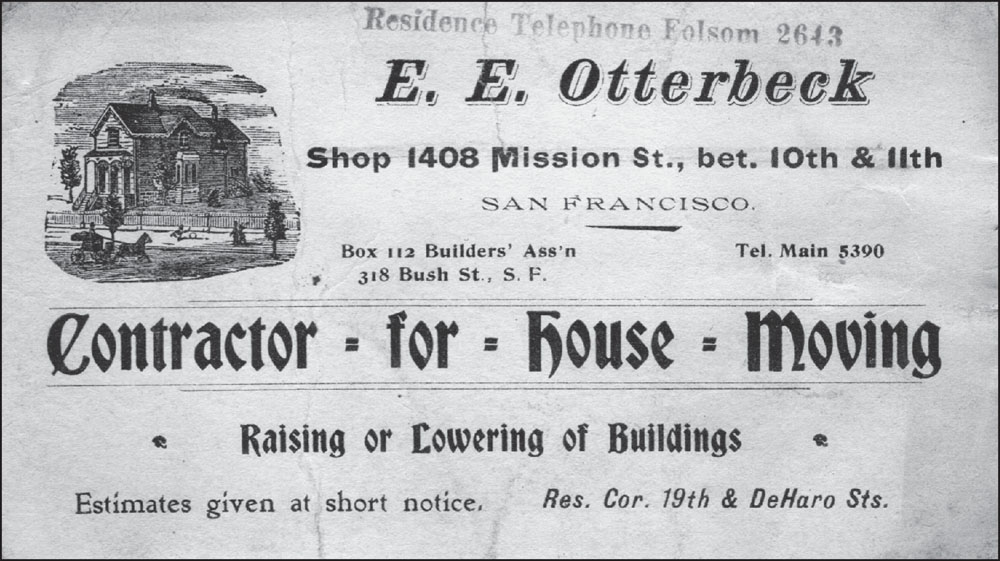

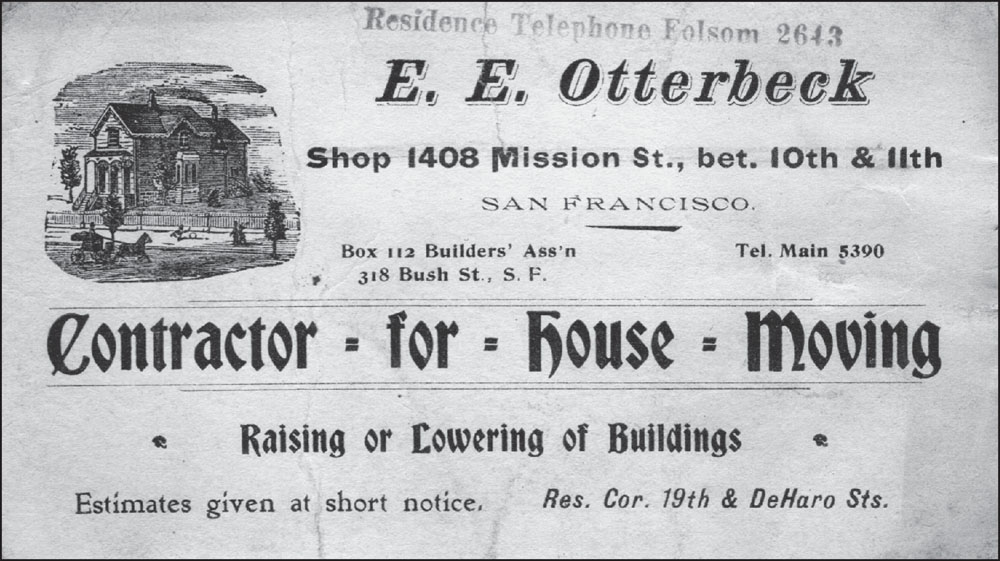

This image of yet another house-moving company advertises the skills of E.E. Otterbeck, who raised, lowered, and moved buildings. Otterbeck became involved in the ongoing war over house mover licensing and, in 1904, requested a repeal of the ordinance requiring a license, declaring it was designed to lock out small house-moving businesses. (Courtesy of Potrero Hill Archives Project.)

Many early house movers also raised and lowered buildings, as street grades were ever changing at the time. In addition to house moving and raising, J.R. Pool’s services also included demolition and the salvaging and selling of second-hand building materials. Because lumber and building materials were hard to come by, moving a structure was often preferred over demolition. (Courtesy of the Glenn D. Koch collection.)

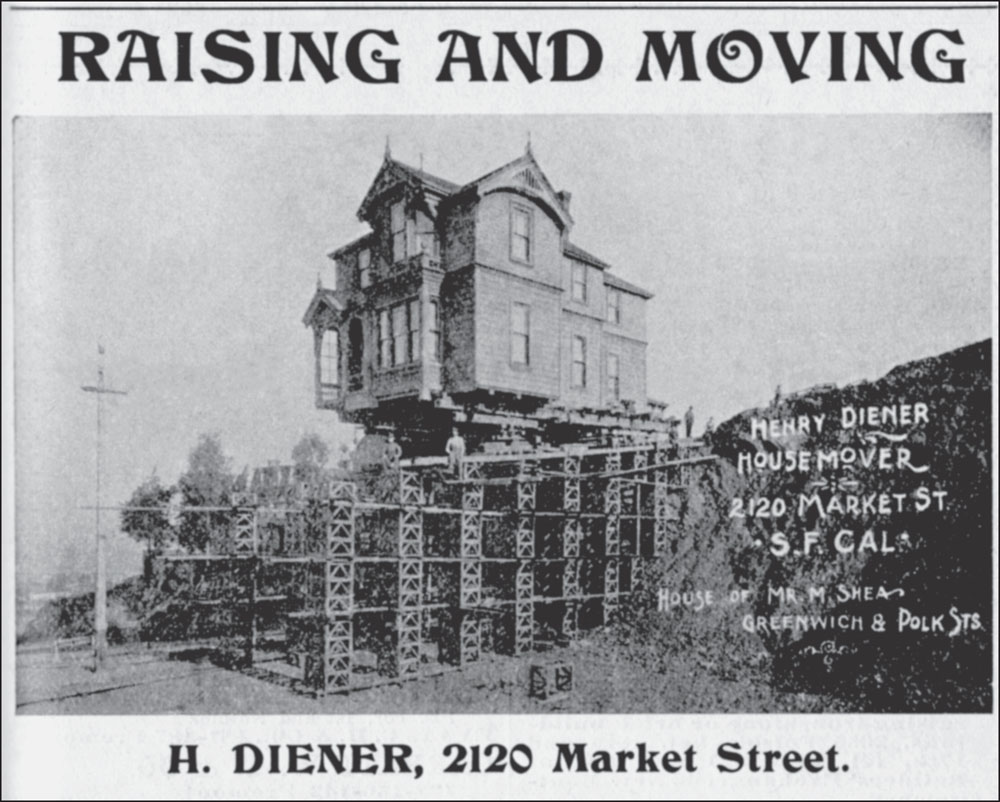

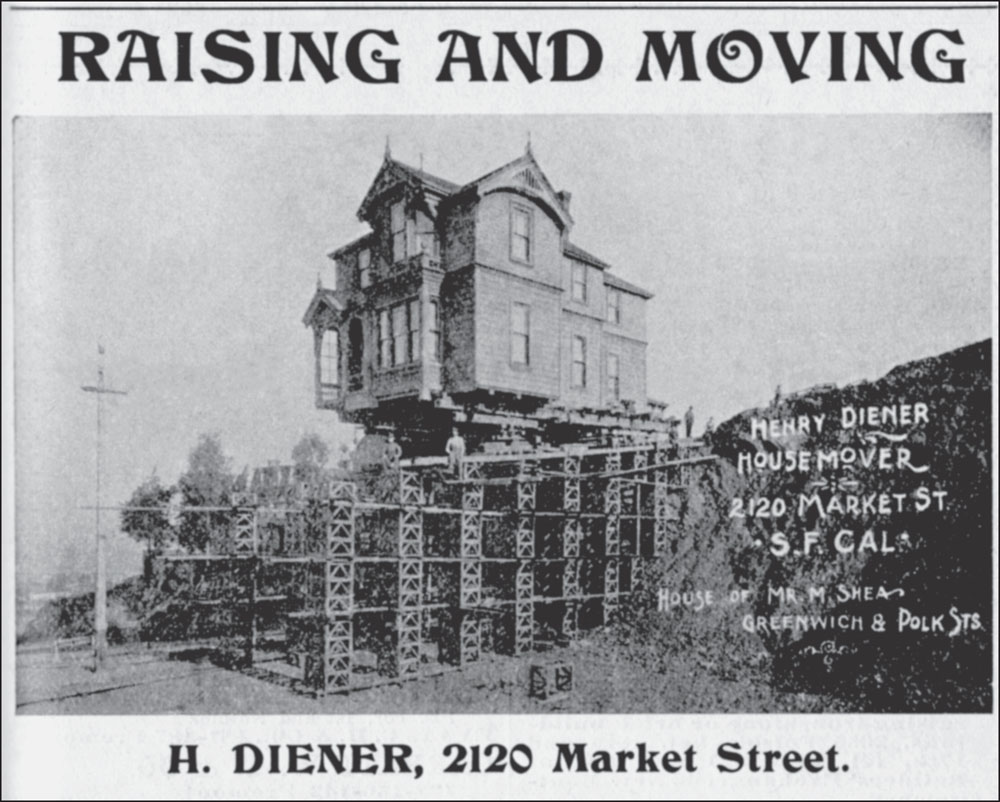

Nothing says “house mover extraordinaire” like a visual, and Henry Diener’s ad from the 1900 city directory displays a remarkable engineering accomplishment during an 1890s move. This is one example of a move likely brought about by street-grading efforts in the city, which rendered some houses nearly inaccessible when formerly level city streets were lowered. (Courtesy of the Glenn D. Koch collection.)

One of many house-moving court cases involved house movers Henry Chester and Patrick Gleason, who alleged that a new tax favored consortia of movers and stifled independents. Some 11 firms had joined together as one umbrella group in order to only pay a single tax. Chester and Gleason formed their own firm as copartners of San Francisco Housemovers’ Company No. 1, under which they then obtained a single license. (Courtesy of the Glenn D. Koch collection.)

In 1866, this building blocked the whole street. Mark Twain, in the San Francisco Daily Morning Call, decried these increasingly common scenarios. He wrote, “For several days a vagrant two-story frame house has been wandering listlessly about Commercial Street, above this office, and she has finally stopped in the middle of the thoroughfare, and is staring dejectedly toward Montgomery street, as if she would like to go down there, but really do not feel equal to the exertion.” (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

Mayor Frank McCoppin was the first official to publicly decry the impact of moving houses, blaming the city’s deteriorating streets on “excessive house moving.” An 1858 news report stated, “Pavements are cut up into ruts by the weight of the buildings hauled over them and teams are driven over the sidewalks to the damage, and sometimes total destruction, of planking and curbstones. Not infrequently the moving of a single old frame, worth lest than $100, will cost three times that amount of injury, for which the public have the whole bill to foot.” (Courtesy of Philip Brent Digital Art and Photography.)

This is one of history’s as-yet-unsolved mysteries. One collection identifies it as a building moved for the Spreckles Mansion in the 1890s, but the Spreckles residence (seen here on the right) was not built until 1913. Additionally, newspaper accounts from July 1913 report that Herbert L. Hatch sought permission to move an unnamed home in this same vicinity. The house sits at Washington Street between Octavia and Gough Streets. (Courtesy of the Glenn D. Koch collection, permission courtesy of the San Francisco Metropolitan Transit Authority.)

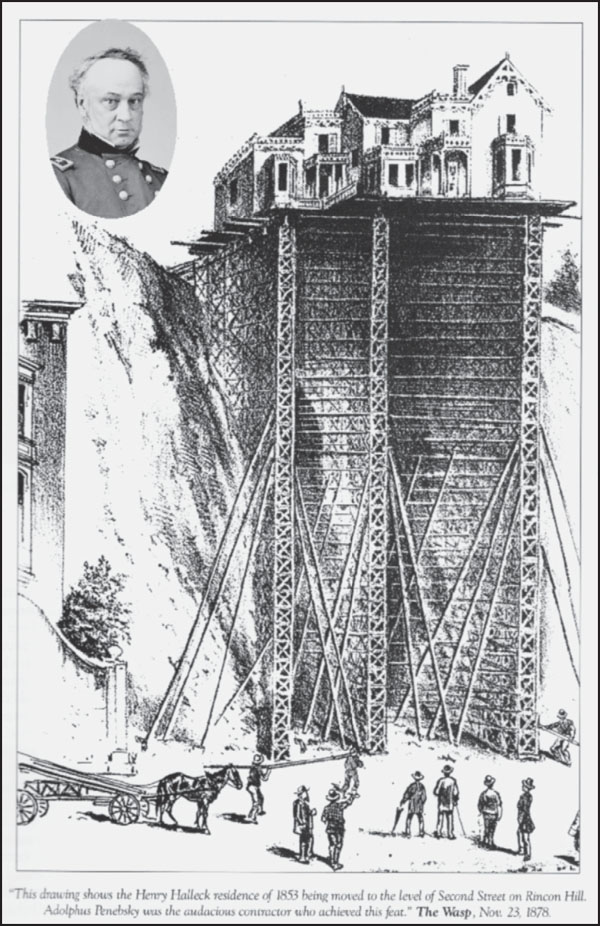

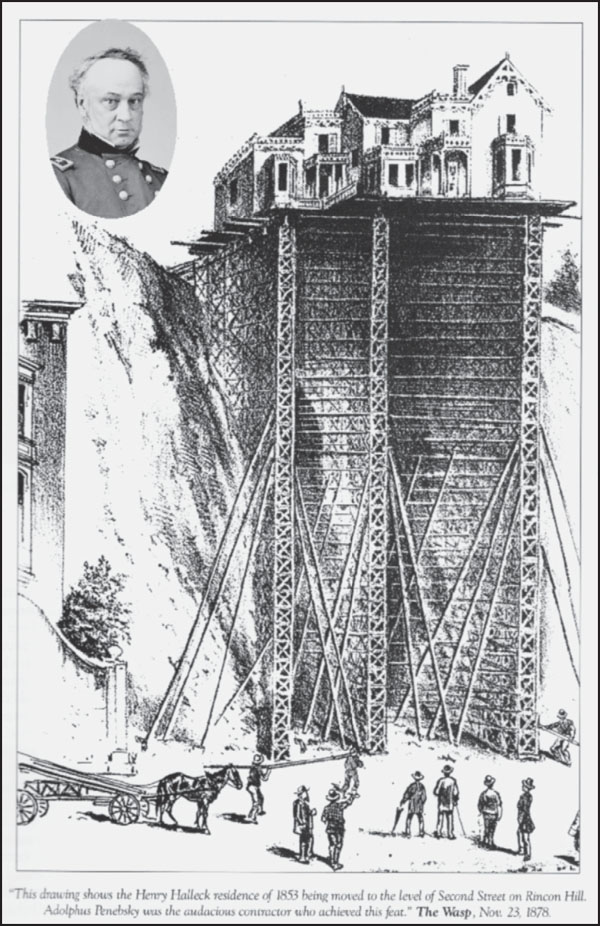

Street grading Rincon Hill left some lavish buildings, such as Henry Halleck’s home, high and dry. This artist’s rendering, illustrated originally in the Wasp on November 23, 1878, shows Henry Halleck’s residence supported by box cribs during its move to the level of Second Street. Cribbing is often used in building moves, along with pneumatic or hydraulic shoring. House owner General Halleck’s image is in the upper-left corner. (Courtesy of Philip Brent Digital Art and Photography.)

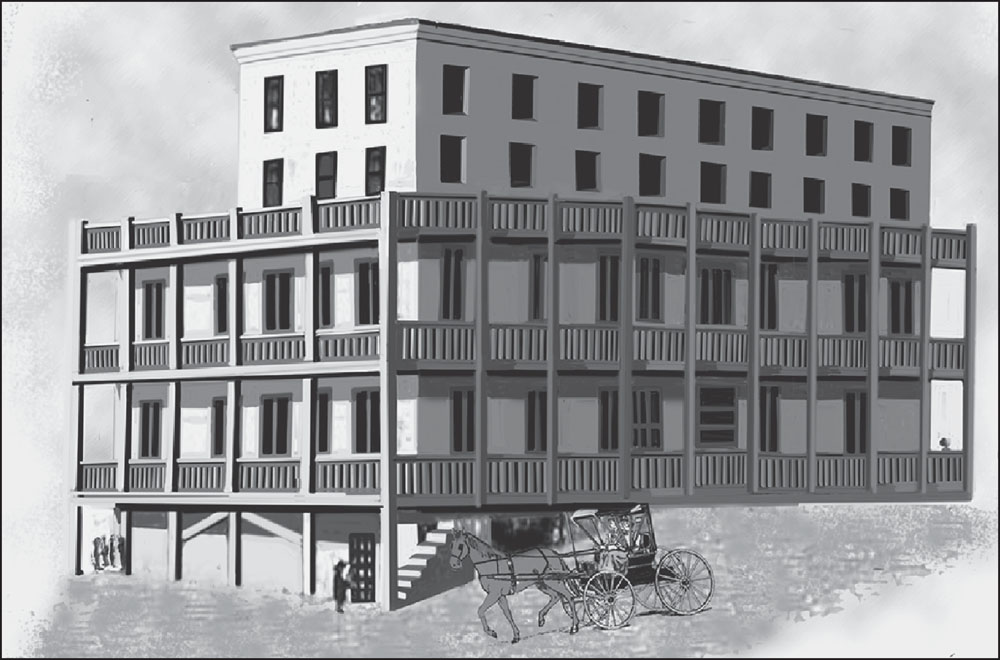

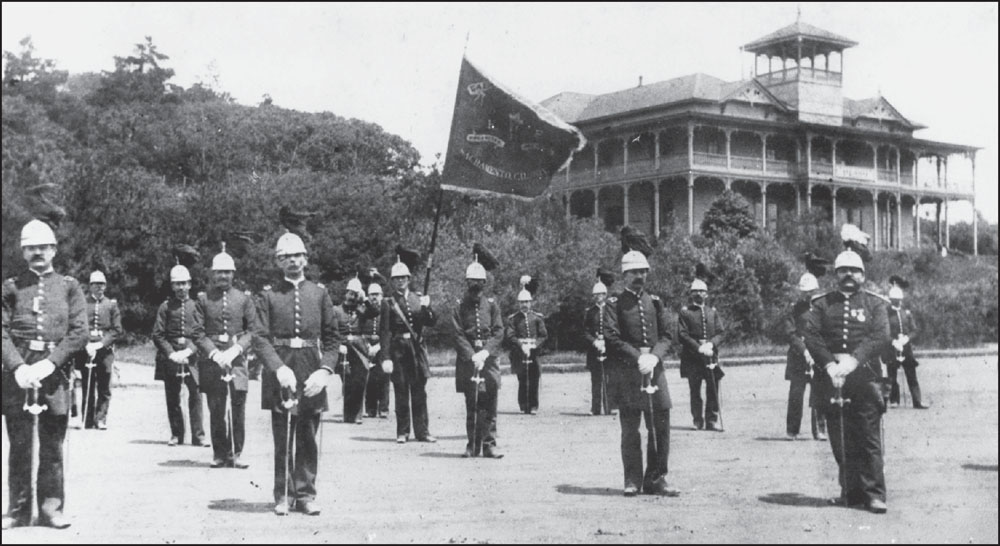

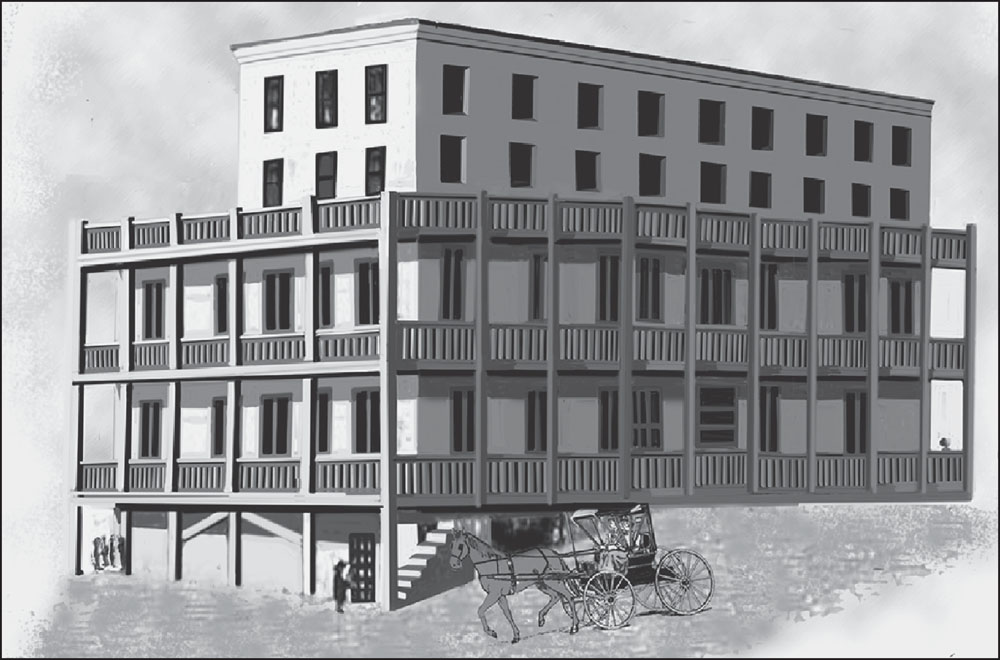

This is a digital rendering of what was the Graham House. The four-story wooden building, lined on two sides by continuous balconies, was shipped in sections from Baltimore and set up on the corner of Kearny and Pacific Streets. It was purchased for $150,000 on April 1, 1850, to serve as San Francisco City Hall. Executive and judicial offices were placed on the upper floors. It burned to the ground in the fire of June 1851. (Courtesy of Philip Brent Digital Art and Photography.)

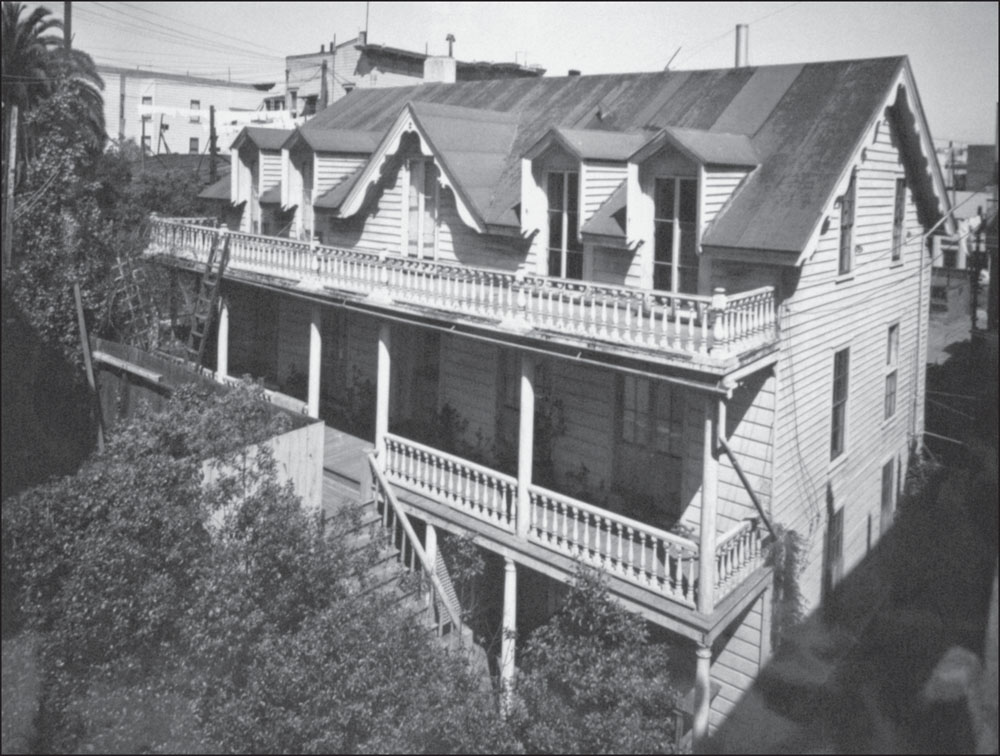

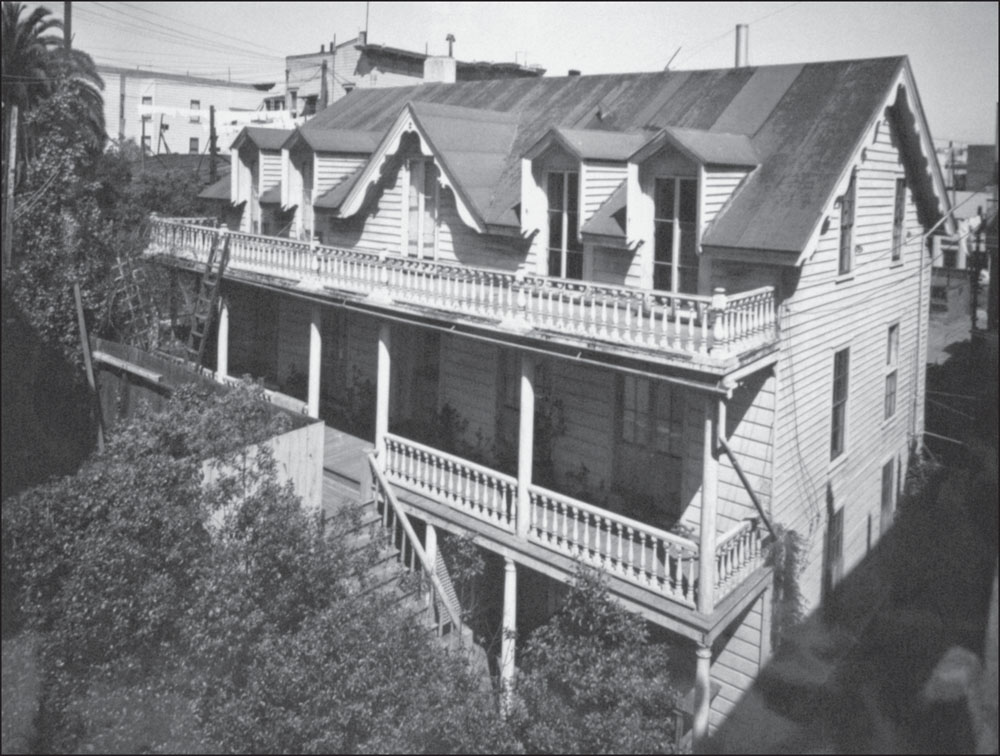

The Phelps House was shipped in pieces to San Francisco via Cape Horn. A 1934 account states that it was “built in 1850 and brought round the Horn from Maine, there being no sawmills here at the time.” However, Abner Phelps’s great-granddaughter maintained that the house had been purchased in New Orleans in 1850 and was shipped in sections from Louisiana. (Courtesy of the San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.)

This is a digital rendering of what is today’s Turk Station Lodge. In 1910, the plantation-style home was moved from the docks in San Francisco to its present location at Turk Station in Coalinga. The house was originally destined for an unknown location in the Pacific Rim, but the deal fell through. The owners of Pleasant Valley Farming Company purchased the home, and a mule train moved it to its present site. (Courtesy of Philip Brent Digital Art and Photography.)

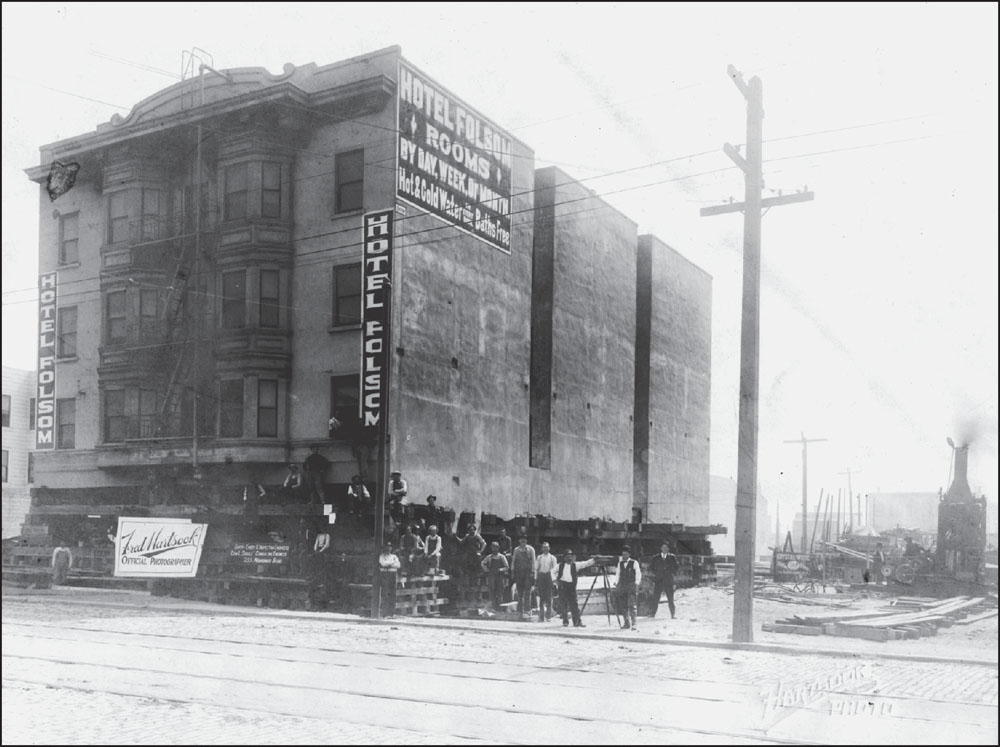

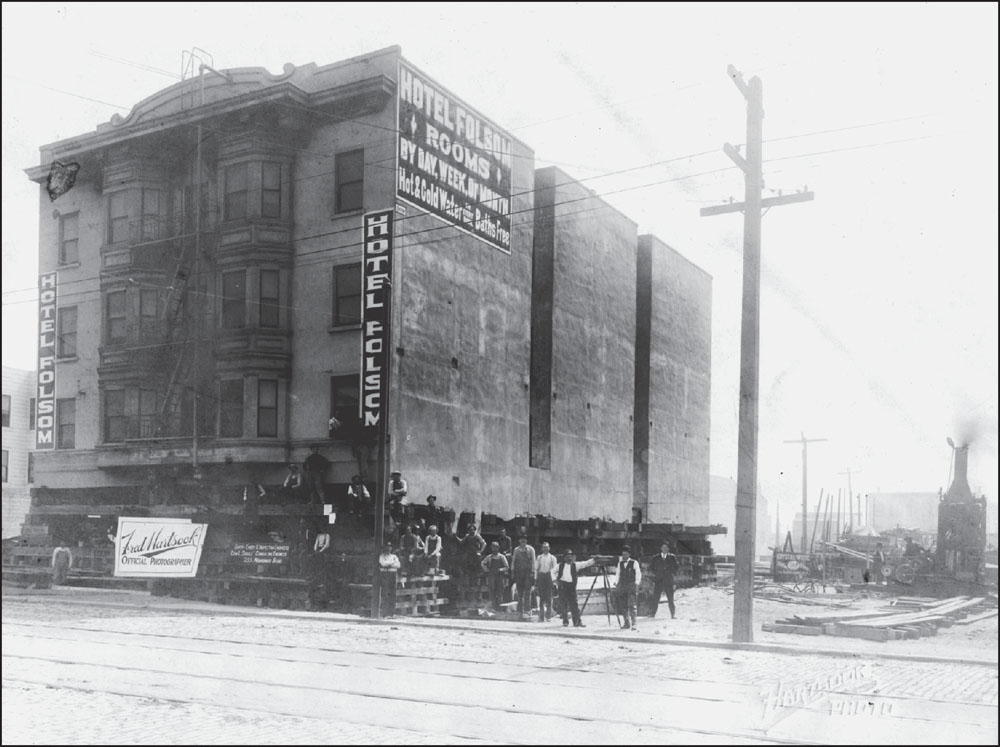

Soon after it was completed in 1907, the Hotel Folsom began sinking in the unstable South of Market soil. It was moved one lot over while pilings were driven into the ground to stabilize it, and a new foundation was created (along with a new commercial first floor, seen in this photograph) on the now-reinforced lot. Then the building was returned to the site. It remains a hotel today, with a new name. (Courtesy of the John Freeman collection.)

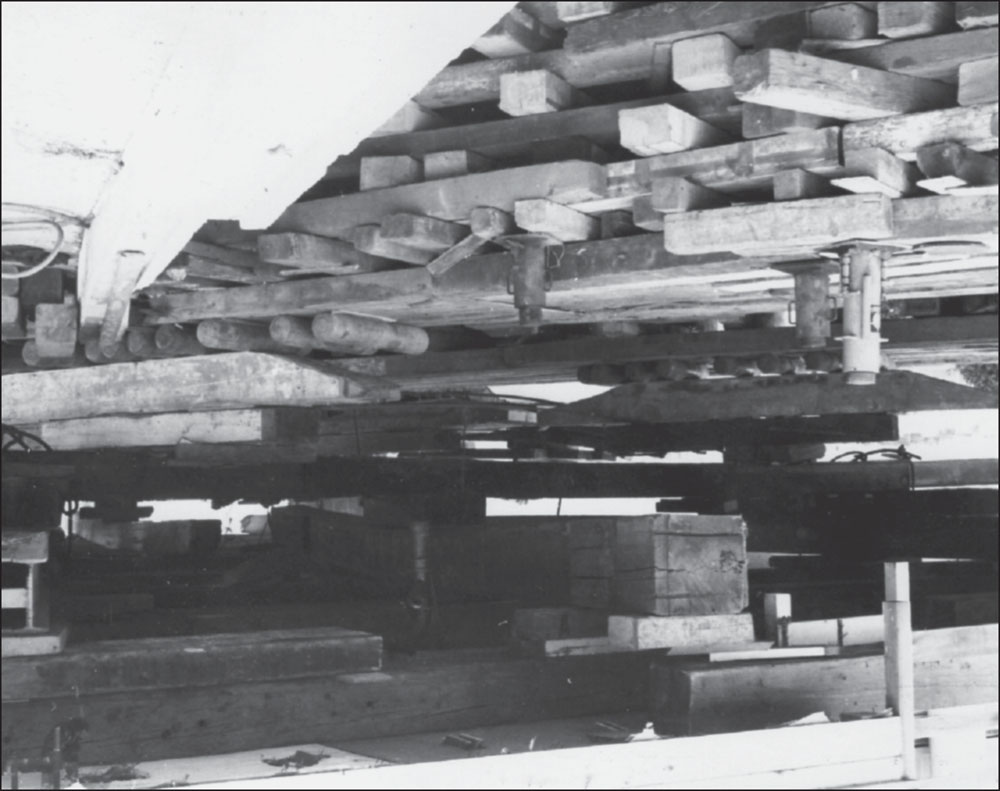

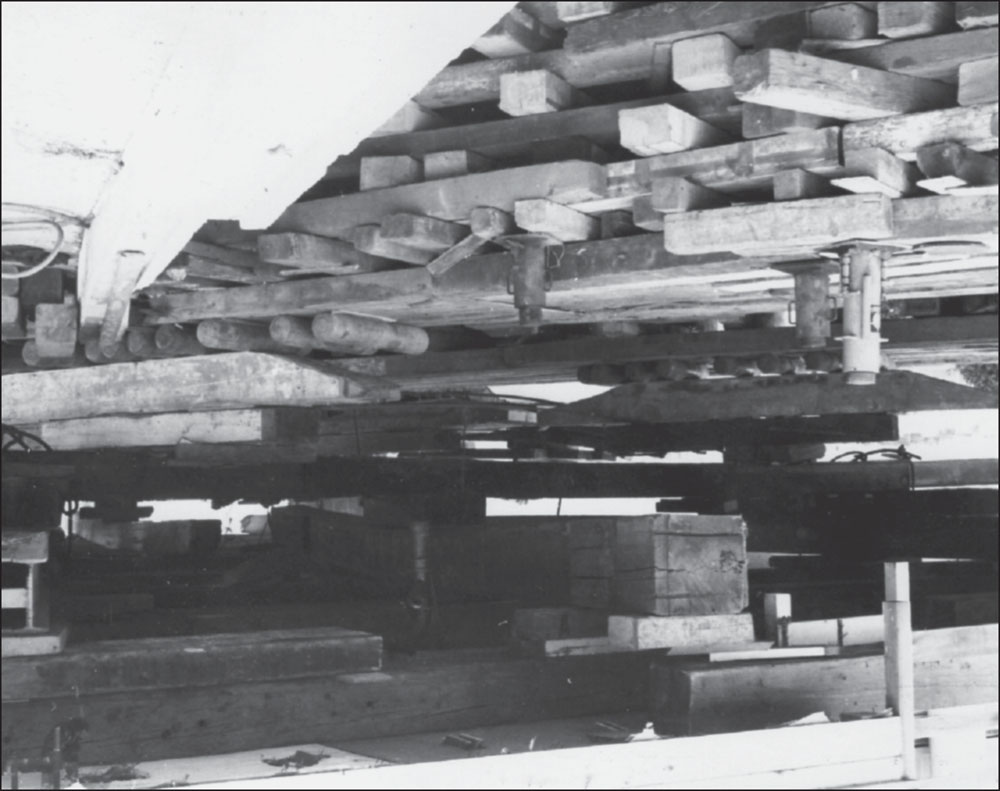

This close-up photograph of the underside of a jacked-up house shows how everything—cribbing, house jacks, and shoes—works together. The shoes are what the building rolls on. The combination of cribbing, jacks, and rollers is essential for moving a building. (Courtesy of the Hubert Trost collection.)

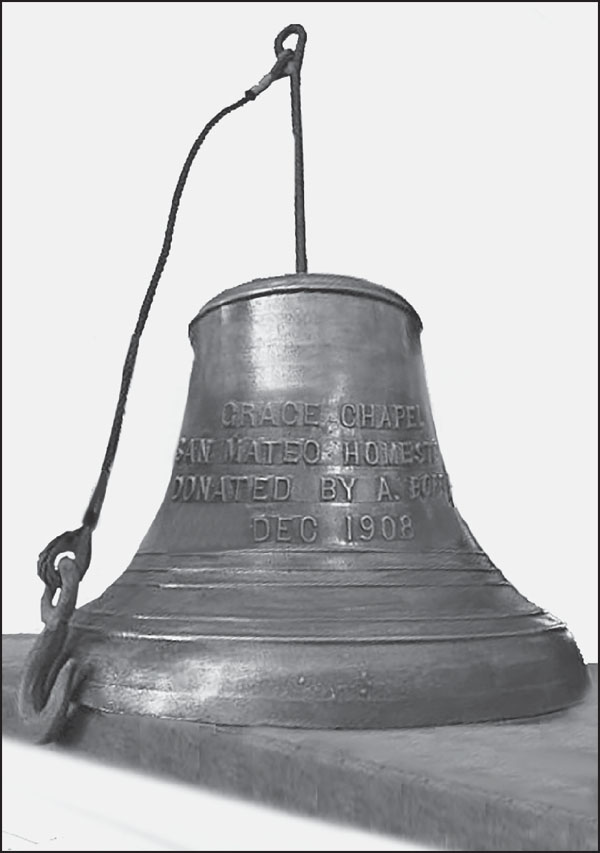

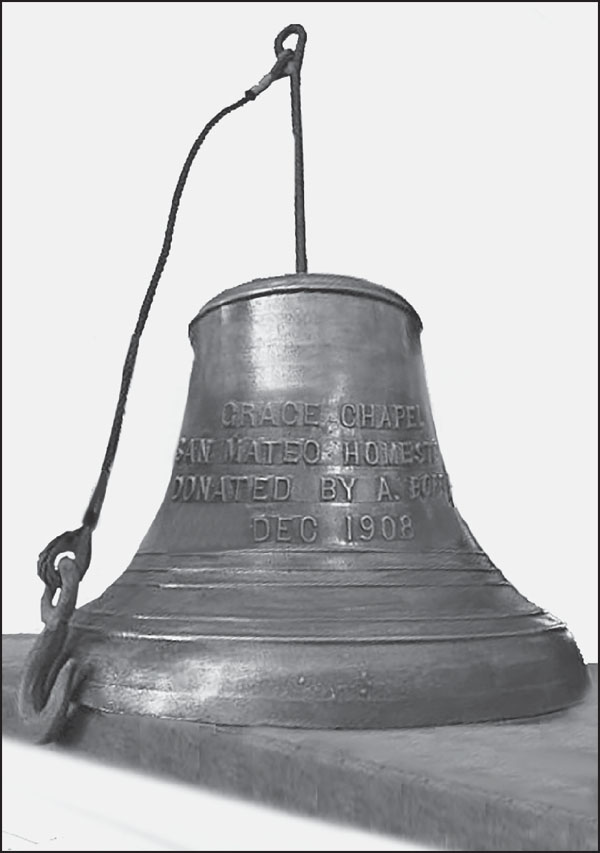

Buildings were not the only things moving in 1908 San Francisco. The W.T. Garrett & Co. foundry created a 300-pound bell for Grace Church, located at El Camino and Highway 92. In the 1950s, the Hillbarn Theater used the bell to end intermissions. In 1968, it moved to Foster City. In 2004, it was stolen. In 2010, it was discovered at a scrap shop in San Leandro and returned to Foster City. (Courtesy of Philip Brent Digital Art and Photography.)

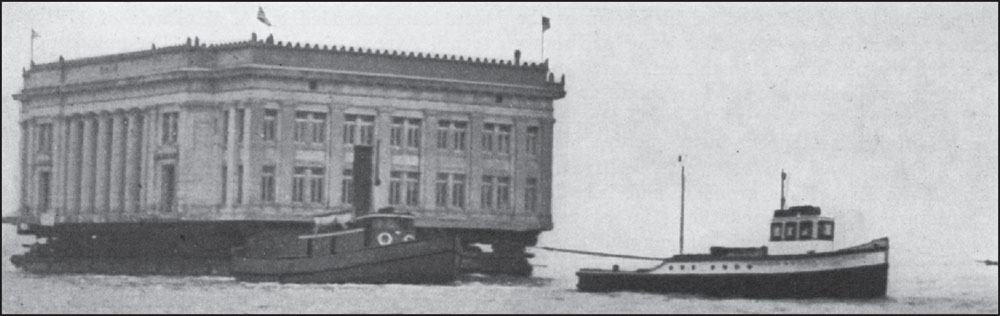

In 1912, the Union Iron Works office building stood in the way of a new powerhouse, prompting the biggest moving effort of its times. The company picked up the 10-foot-deep, 50-foot-high, four-story building, placed it on the barge seen here, and floated it to nearby Hunter’s Point. When a yard packed with heavy materials limited access to the barge, the workers simply jacked the structure nine feet high and moved the building over the obstacles. (Courtesy of the John Freeman collection.)

In 1882, the Daeman brothers built the Casino Restaurant and Bar in Golden Gate Park. This is a photograph of the original Casino. While it was a moneymaker for the family who later leased it, its reputation for serving liquor conflicted with the city’s image of a family-oriented tourist attraction, and the pressure was on to move it away from the center of park activities. (Courtesy of a private collection.)

In 1890, the Casino was moved a short distance down from the Conservatory of Flowers to face today’s John F. Kennedy Drive and was raised up one story. Still, its reputation as a saloon rankled those who viewed it as an immoral establishment. In this location, its service as a casino was very short-lived. It temporarily became a museum until the two-story Casino was moved to the end of the speedway to become a clubhouse. (Courtesy of a private collection.)

Here is the revamped Casino with its new second story. In 1896, Stewart Menzies bought the building and moved it out of the park to the corner of Twenty-Fourth Avenue and Fulton Street, where he ran it as a popular and lively roadhouse—a much more acceptable venture when removed from the public eye of Golden Gate Park. (Courtesy of a private collection.)

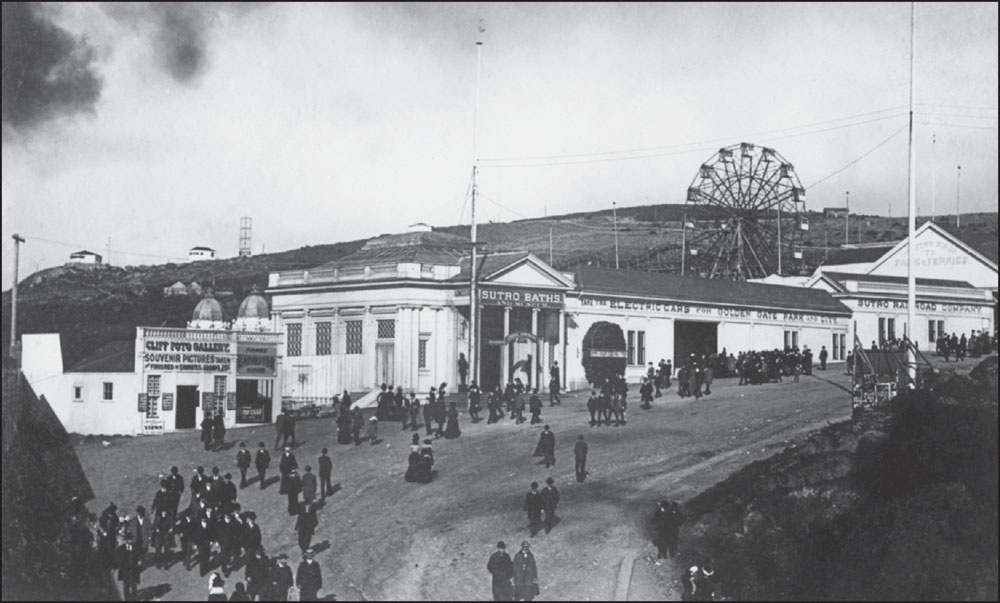

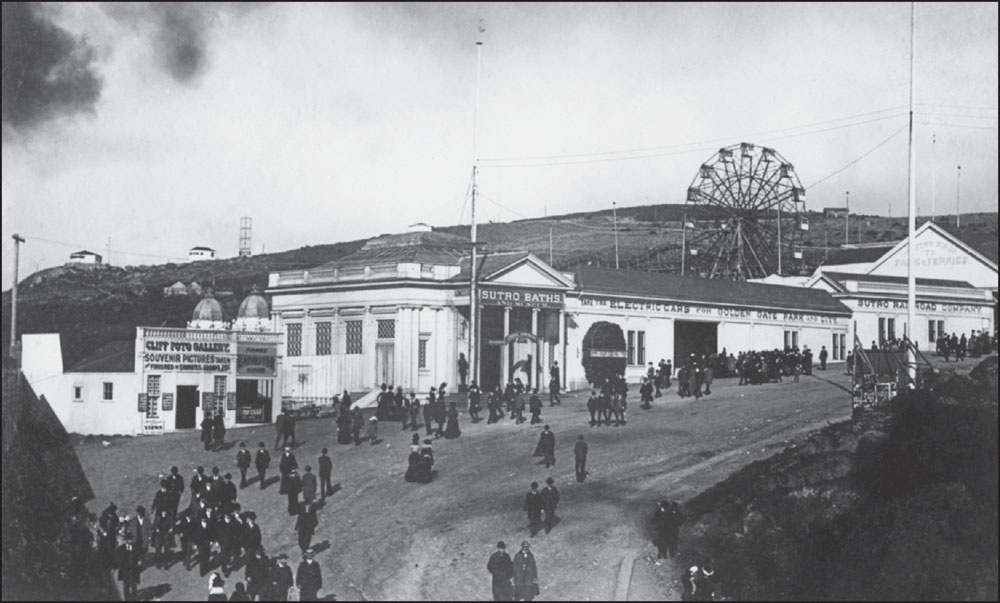

The Firth Wheel was one of the most popular crowd-pleasers at the 1894 California Midwinter International Exposition. George Ferris originally invented the ride for the Columbian Exposition. M.H. de Young got J.K. Firth & Co. to make him a smaller one for the exposition. After the exposition ended, Sutro arranged for it to be transported to his property. Mover James Bain was killed in the process. (Courtesy of the Dennis O’Rorke collection.)

The Firth Wheel installed at Adolph Sutro’s midway complex was 100 feet in diameter, had 16 carriages, and offered dramatic seaside views for those who took its 20-minute-long ride. The massive wheel, illuminated by hundreds of electric lights, even acted as a beacon for ships approaching the Golden Gate at night. Seventeen years later, Sutro’s investment proved unprofitable, and the wheel was torn down after years of neglect. (Courtesy of the Dennis O’Rorke collection.)

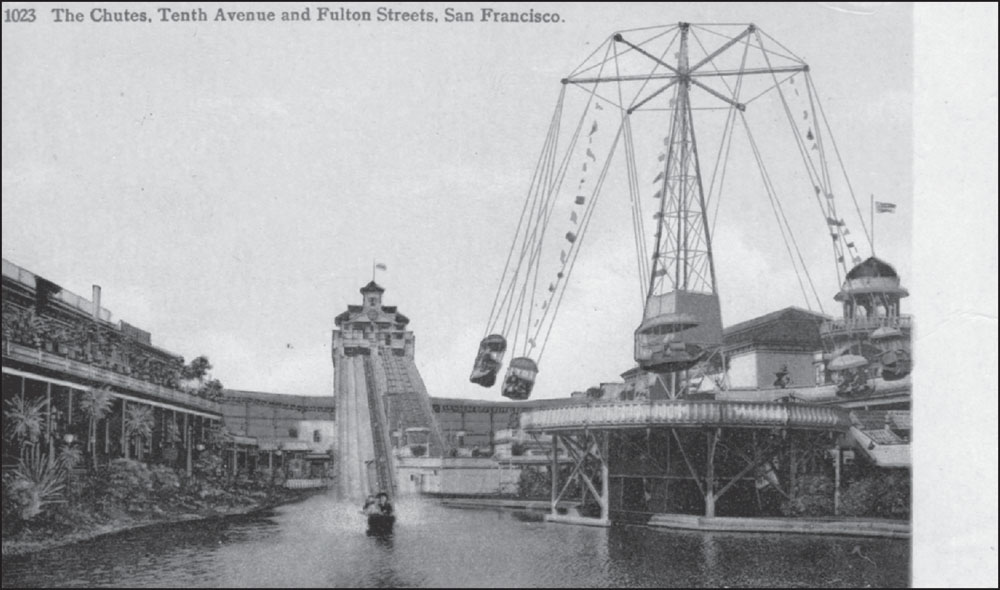

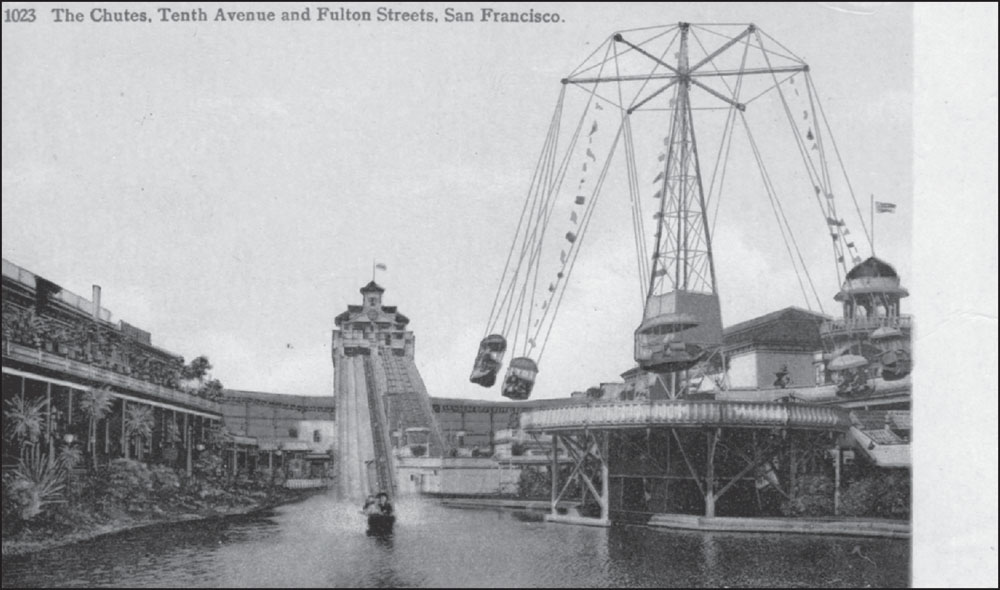

An amusement park does not move like a building; it must be disassembled and rebuilt each time. The Chutes saw three locations between its 1895 opening on Haight Street and its final location at Fillmore and Fulton Streets in 1911. Attractions were modified to suit their new locales, and some never were reassembled. This postcard depicts the Chutes at Tenth Avenue and Fulton Street in its second location, from 1902 to 1908. (Author’s collection.)

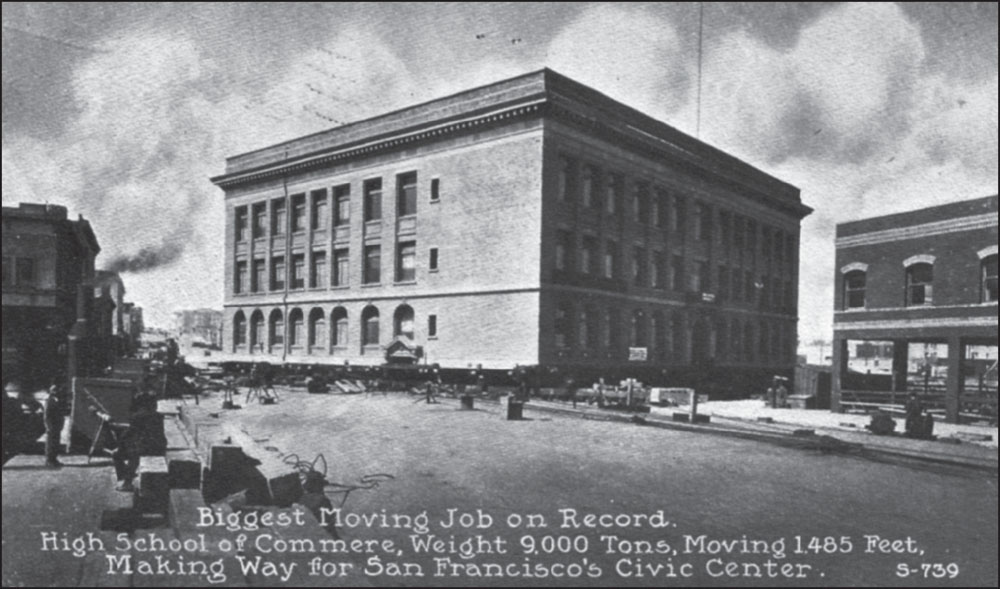

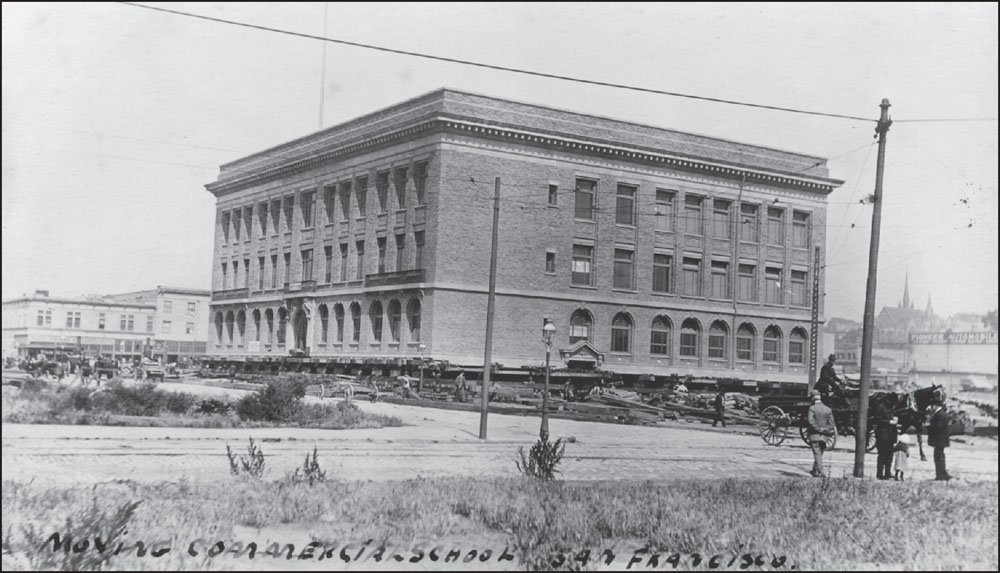

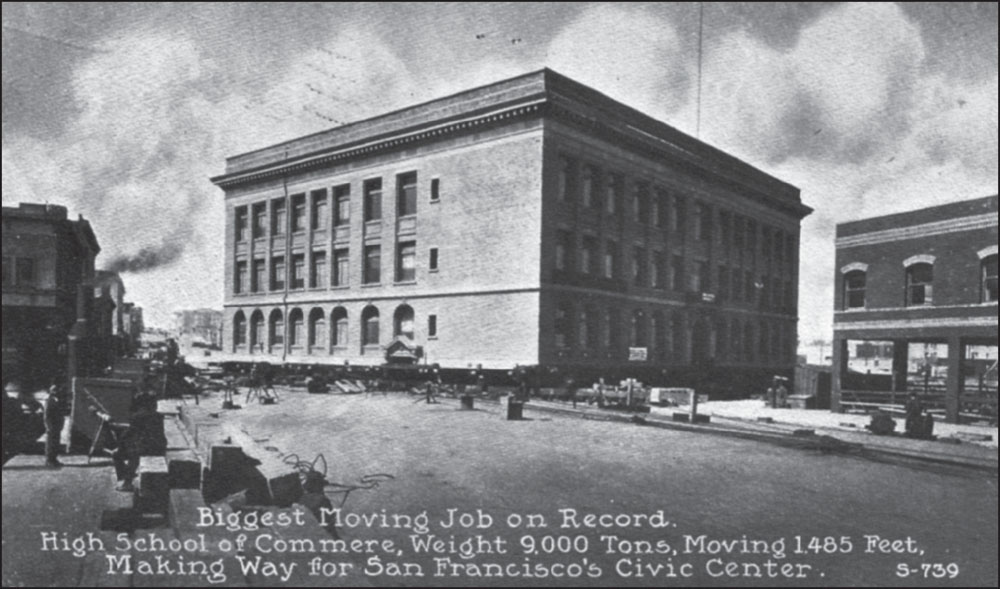

In 1913, the proposal of a new civic center in San Francisco prompted the move of a huge structure weighing some 9,000 tons, billed as “the biggest moving job on record.” The 67,000-square-foot building, designed by architect Newton Tharp in 1907, was completed in 1910. Only two years later, in 1913, Commercial High, also known as High School of Commerce (misspelled on this postcard), was moved to 170 Fell Street. This vintage postcard shows the building jacked up and ready to go. (Courtesy of the Lew Baer collection, www.postcard.org.)

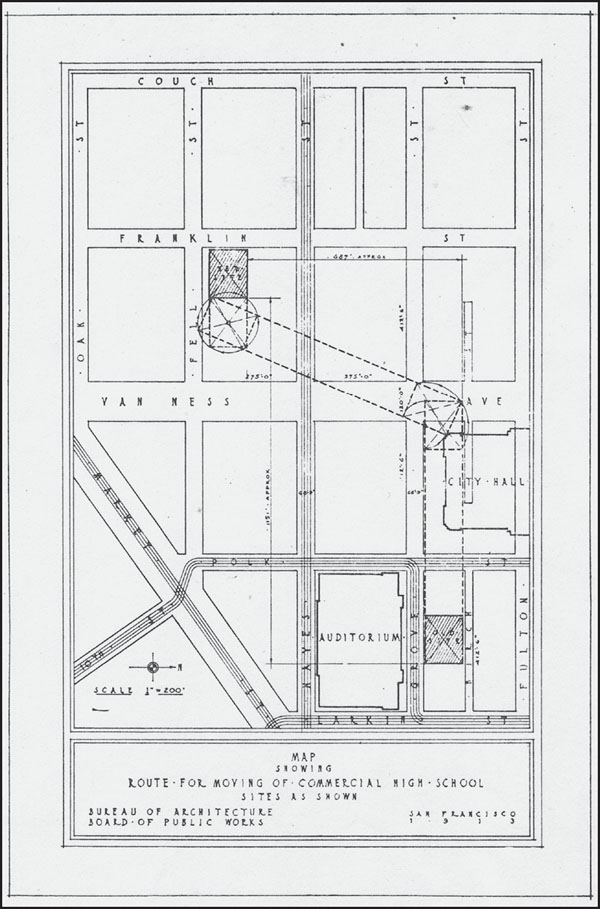

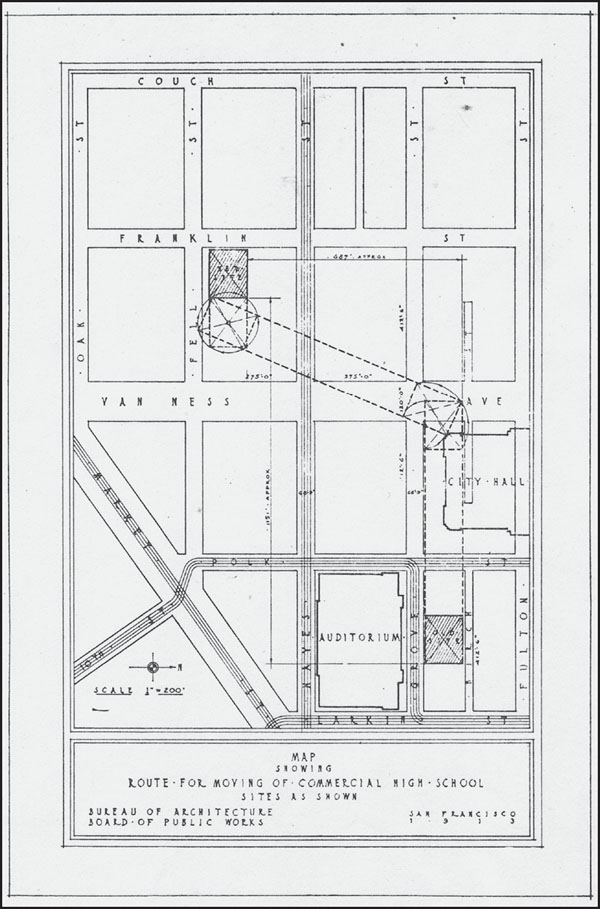

This 1913 map shows Commercial High’s curious route. Its original location was mid-block on Grove Street. The building was moved across vacant land one and a half blocks to Van Ness Avenue, rotated 22.5 degrees in the middle of the intersection of Grove Street and Van Ness Avenue, and crossed two vacant blocks to mid-block on Fell Street, where it was rotated again before being placed on the northeast corner of Fell and Franklin Streets. (Courtesy of the John Freeman collection.)

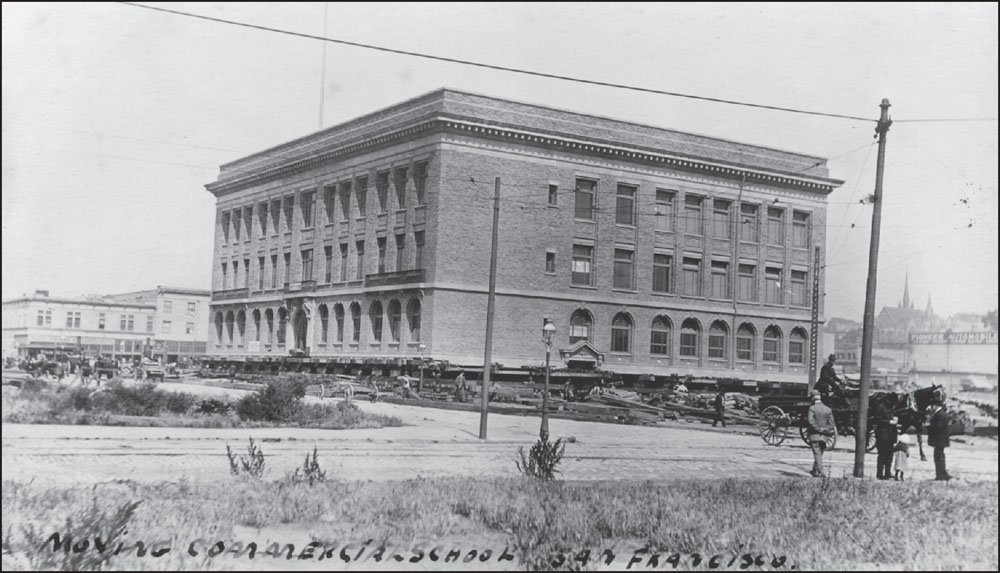

Many rollers, as seen in this photograph, were necessary in order to move a building the size of Commercial High. Movers used laurel rollers that were four feet long and eight inches in diameter. The shoes rested on these rollers and were extra long at the heavier front of the building to lend added support. Steam donkeys provided the power to pull the cables. (Courtesy of the John Freeman collection.)

This photograph shows how steam donkeys were used for winching and pulling buildings during moves. The 50-horsepower, double-spooled donkey engines pulled one-fourth-inch cable. This tackle pulled on the main cable, which was seven-eighths of an inch thick and rated at 27 tons. The main cable pulled on the eveners, which applied force at the rear of the building to actually push it, preventing the platform from being pulled apart during the move. (Courtesy of the John Freeman collection.)

The Newton J. Tharp Commercial School was named in honor of Tharp’s many design contributions. In 1951, the school housed the San Francisco Unified School District’s administrative offices, but in 1989, the building was damaged in the Loma Prieta earthquake. Unable to qualify for federal money to retrofit it because the damage was not quite up to the red-tag criteria, the school at 170 Fell Street remains boarded up and unsafe for use. (Photograph by Beni C. Bacon.)

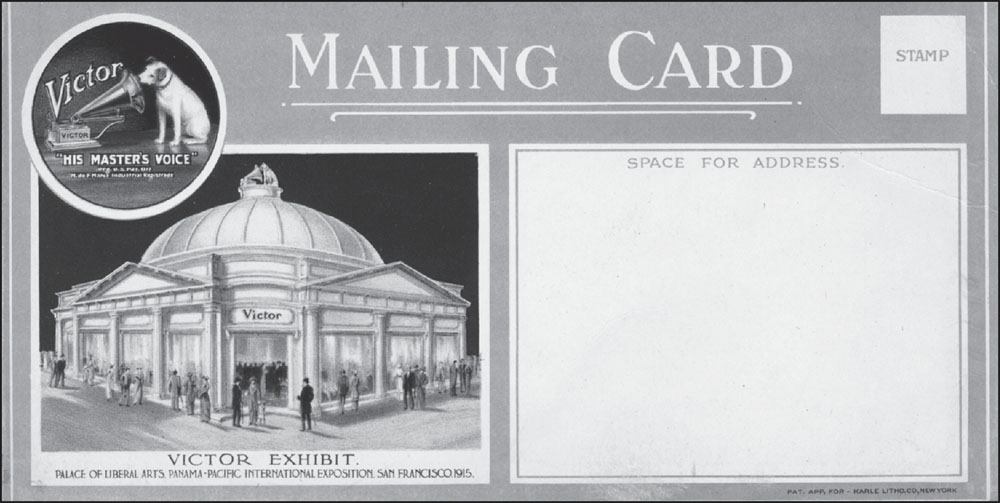

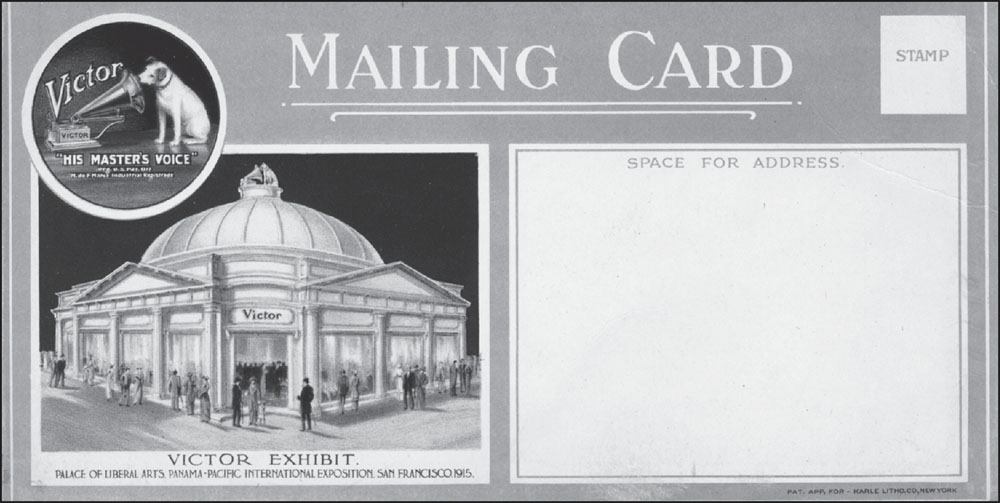

This postcard is the only surviving image of the Victor Talking Machine Company’s pavilion inside the Palace of Liberal Arts, before it was moved from the Panama–Pacific International Exposition (PPIE). The talking machine represented high technology in 1915. Regularly scheduled piano and vocal recitals alternated with recordings chosen from a library of over 7,000 78-rpm discs played on the turntables of two hand-painted Victrola consoles. (Courtesy of the Glenn D. Koch collection.)

When the exposition ended in 1916, the pavilion was dismantled, barged across San Francisco Bay to San Rafael, and floated up the San Rafael Canal to the home of Leon Douglass, who eventually sold it to the San Rafael Improvement Club for $500. Members had it moved a second time to its current location. This image shows the back end of the pavilion building, which is behind a fence and surrounded by shrubbery. (Photograph by Beni C. Bacon.)

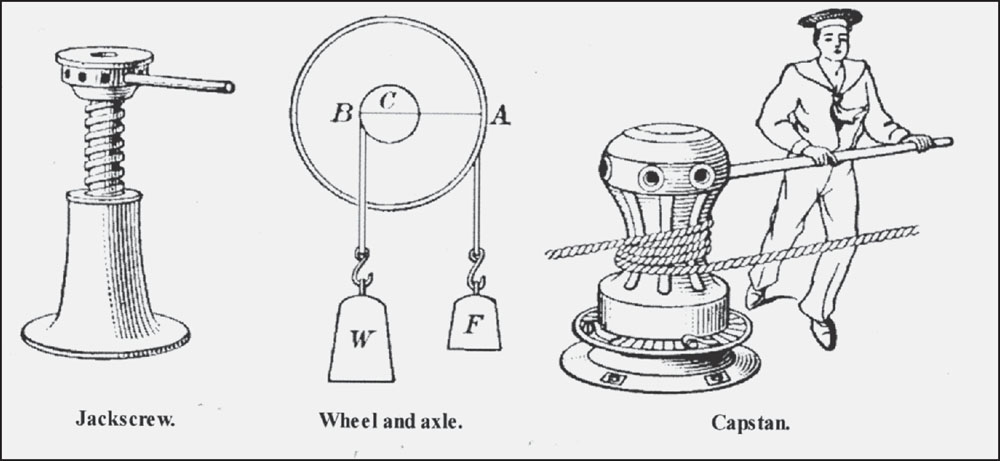

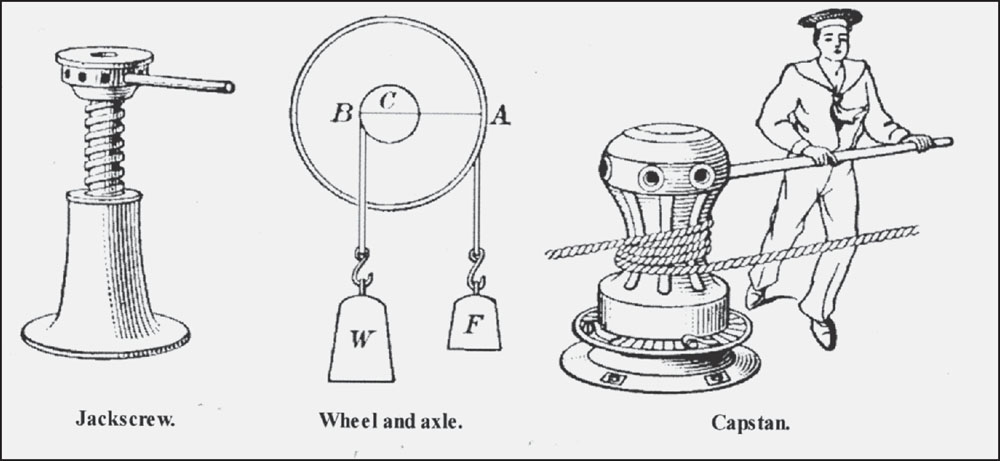

Early moving equipment consisted of jackscrews, capstans, cables, and winches. Hydraulic, computer-assisted jacks are used today, but early lower-tech jackscrews were manually turned to lift the structure off its foundation. Capstans turned via two-horse teams. As the horses circled, stepping over the cable each time, the cable would slowly pull up on the capstan and move the house. Horses were preferred until the 1940s, when trucks began using gear-driven winches powered by engines. This image from Mechanics magazine, published in London in 1824. (Courtesy of the Glenn D. Koch collection.)

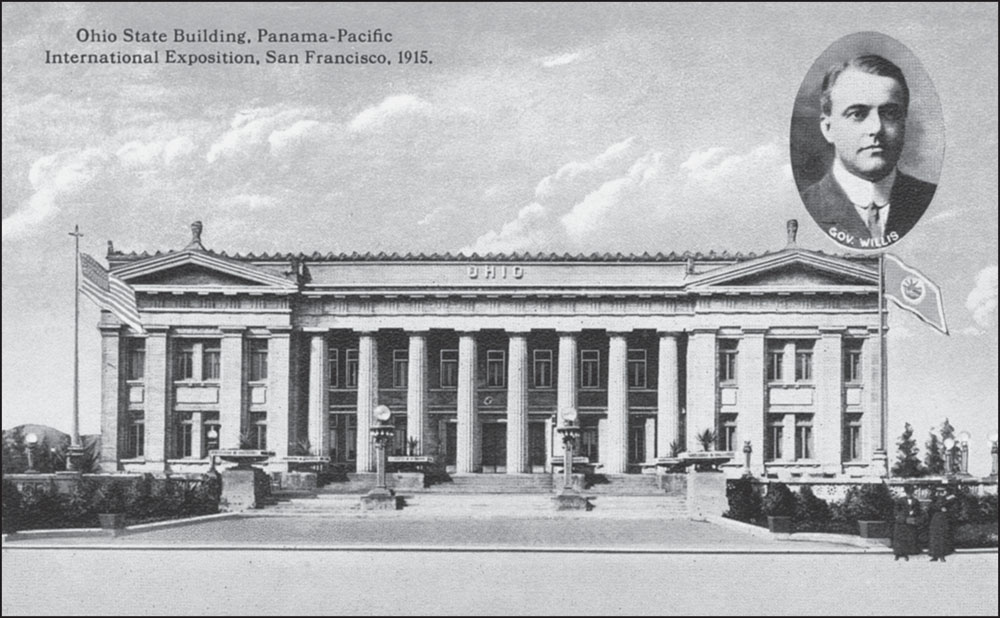

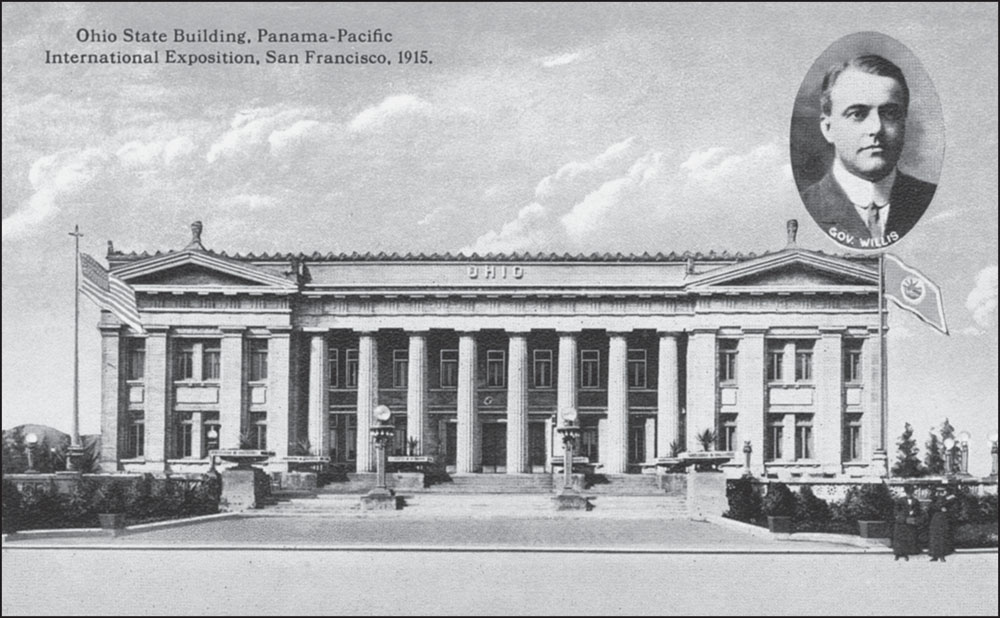

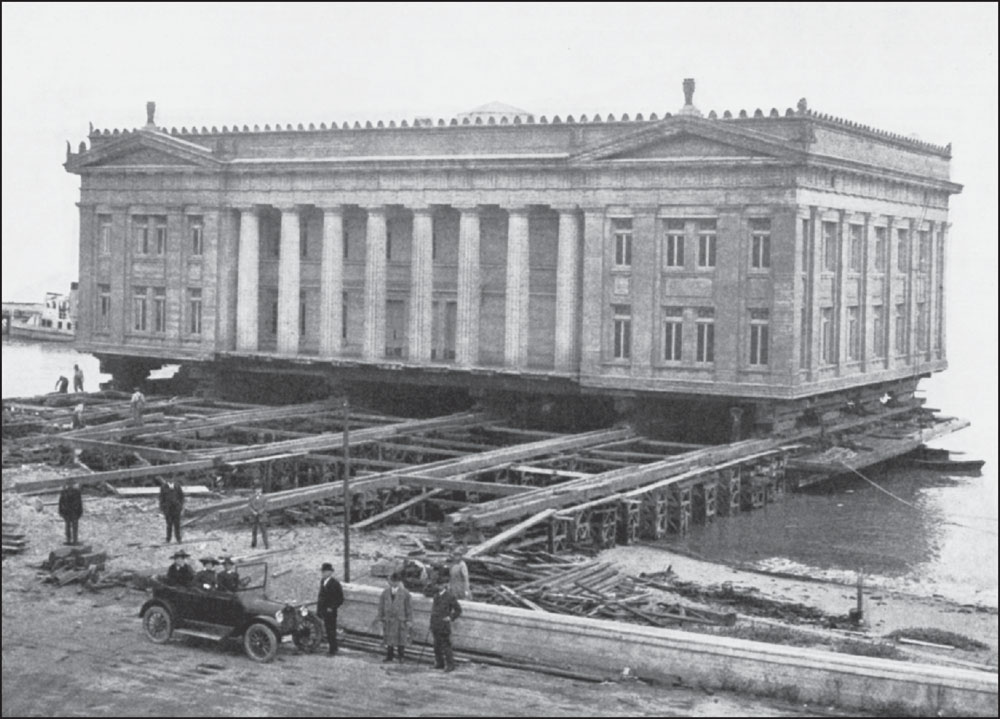

The Ohio State Building at the 1915 Panama–Pacific International Exposition was a replica of the state’s capitol building in Columbus. After the fair ended, it was purchased by group of investors who barged it 30 miles down the San Francisco Bay to the San Carlos Harbor to make it into a clubhouse. Mover Herbert L. Hatch stated that the 800-ton, 133-by-85-foot Ohio State Building was the “largest, heaviest piece of freight ever transported on salt water.” (Courtesy of the Glenn D. Koch collection.)

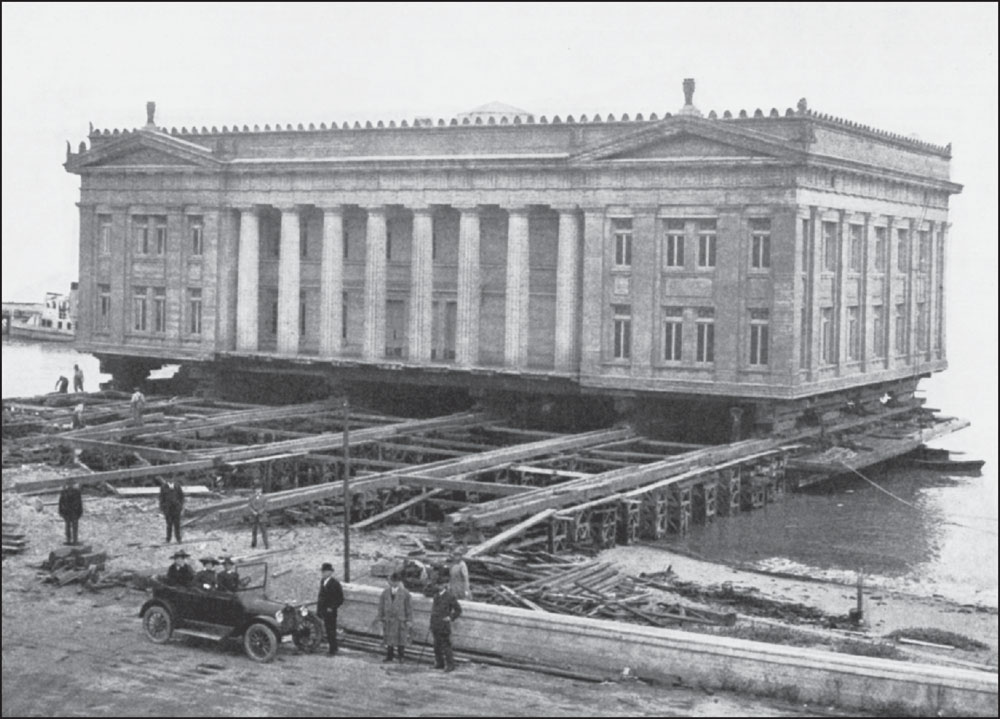

The Ohio State Building was one of the largest of the state buildings at the PPIE. Here, it is being moved from shore onto the barges at the water’s edge. The building sat 600 feet back from the beach at the exposition. It had to be raised (using 170 jackscrews) and moved (via 250 rollers). It was pulled onto the barges by horses hitched to house-moving capstans. (Courtesy of the Glenn D. Koch collection.)

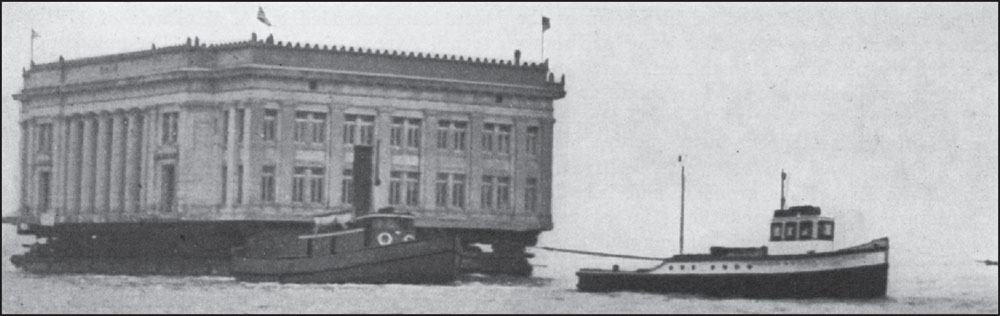

At low tide, the Ohio State Building was lowered onto two 500-ton barges. When the tide rose, several tugboats moved it downstream, but unusually strong winds carried the barge past its destination, and it almost collided with the Dumbarton Bridge. It was moved into position at high tide and settled onto its foundation when the tide went out. Filled land created the base for a new ground floor, converting the building from two stories to three. (Courtesy of the Glenn D. Koch collection.)

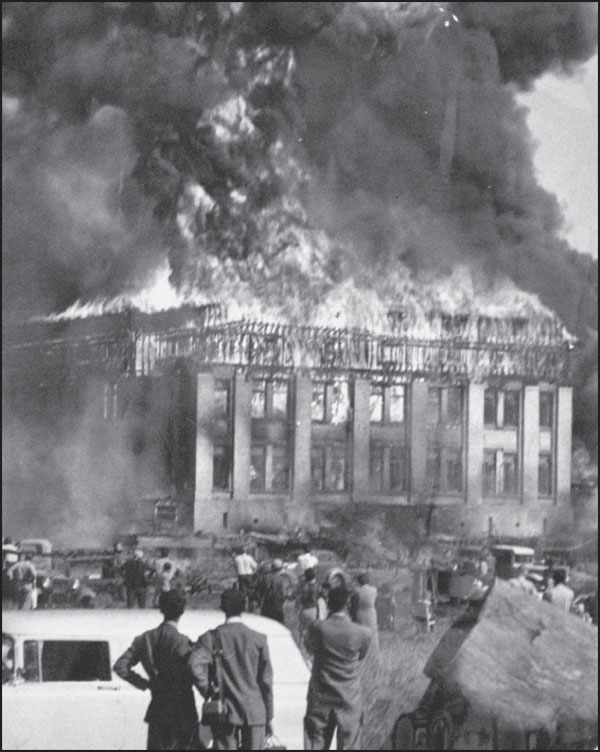

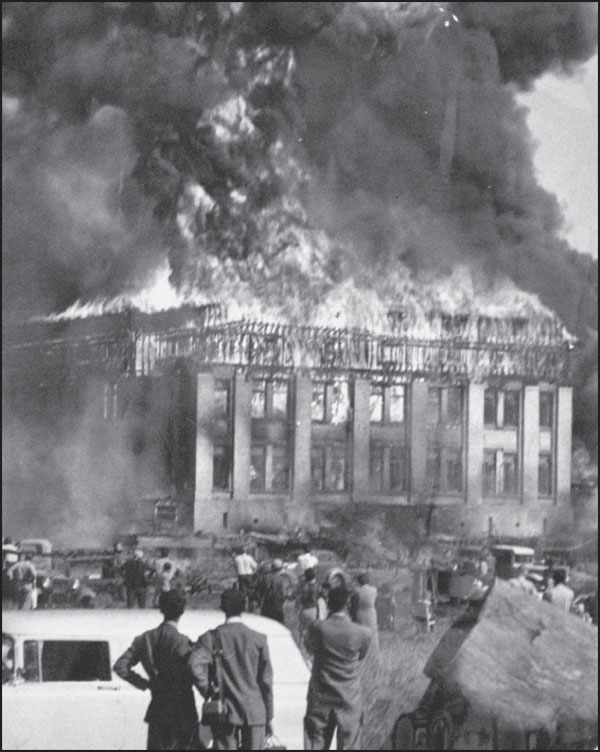

When the country club ran out of funds, the building was abandoned. Charles Cooley, who operated an airport next door, bought it but then decided to sell his airport. The building was slated to be moved again, but a dispute arose over how long it was taking. On December 14, 1956, the Ohio State Building was intentionally burned to the ground as the fastest way of clearing the property. This photograph captures its final fate. (Courtesy of the San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.)

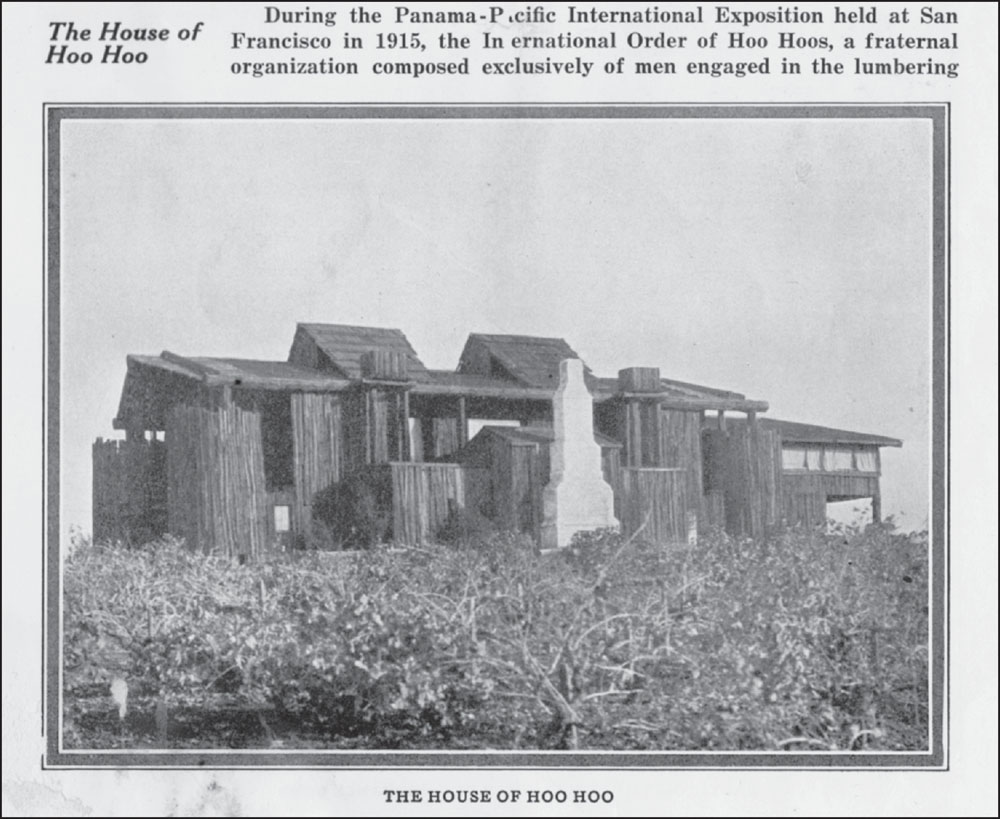

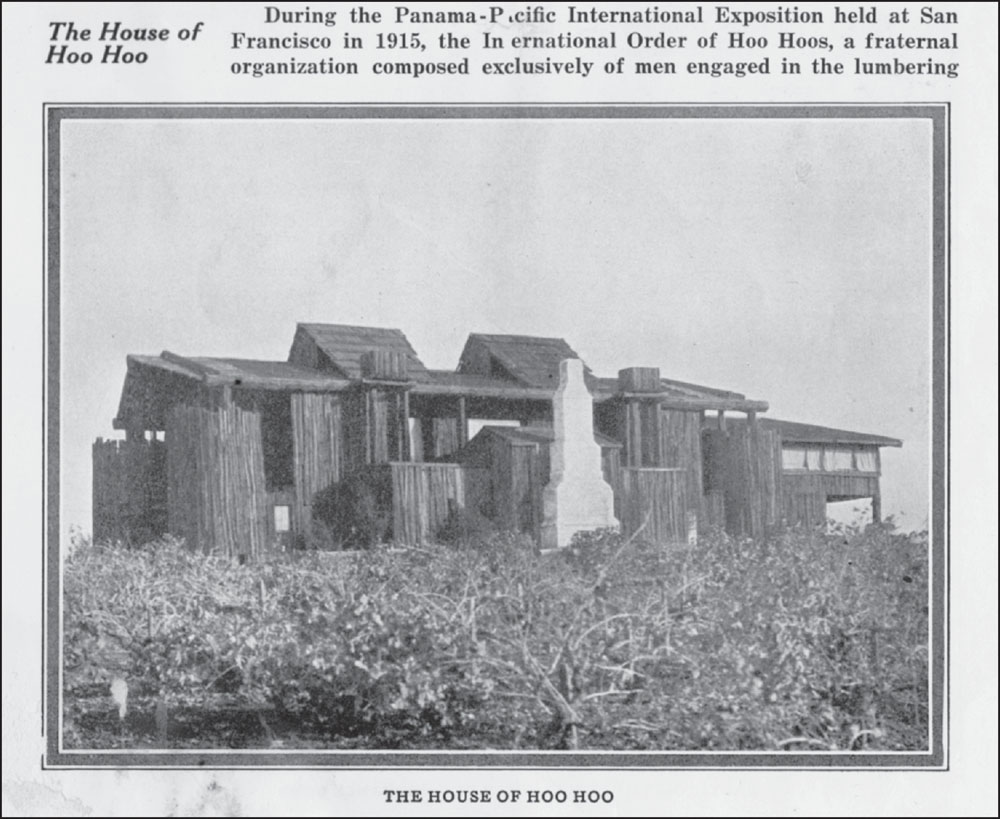

The Lumbermen’s Building and House of Hoo Hoo was moved from the PPIE to Monte Vista, about 40 miles south of San Francisco. The building was 100 feet long, covered in bark, and originally contained a lumbermen’s exhibit. In 1916, it was taken apart, moved by the lumbermen, and reconstructed on the top of Inspiration Point. (Courtesy of the Glenn D. Koch collection.)

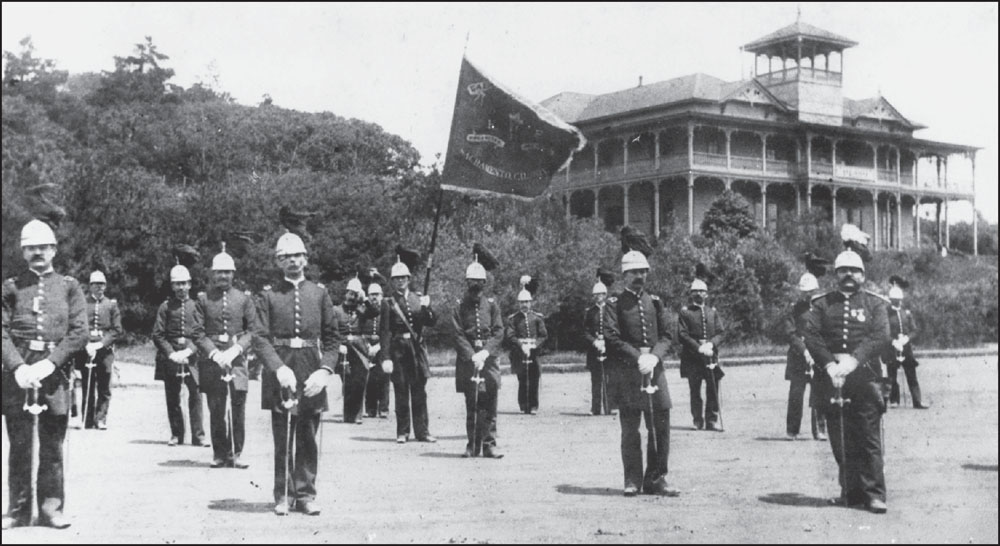

In 1914, work began on the construction of the Panama–Pacific International Exposition grounds on the San Francisco waterfront, including the lower Presidio. The Fort Point Coast Guard Station became an obstacle to the exposition’s plans for building a planked auto racetrack on the same site. This image shows the building in the background prior to the move, with the old airfield in the foreground. (Courtesy of the Robert W. Bowen collection and the Presidio Trust.)

The PPIE bore the cost of moving the station 700 feet to its present location. It also cost the exposition $19,000 to install a new steel boat launch at the new site. This is another pre-move photograph of the old 1887 Coast Guard station, first established at the west end of Crissy Field and decommissioned in 1990. (Courtesy of the Robert W. Bowen collection and the Presidio Trust.)

While today vertical moves in San Francisco are some of the last major building moves taking place in the city, vertical moves were also an integral part of early building relocation projects. This is the original barracks building in the Presidio, constructed in 1862 as part of the first major expansion of the Presidio. (Courtesy of the Presidio Trust.)

The specifics have been lost, but in 1885, the Presidio barracks received an additional story, either by removing the roof and making a new story on top of the old one or by jacking up the original building and constructing a new first floor. If the former is the case, very little of the original 1882 design is left. This is a modern photograph of the barracks today. (Courtesy of the Presidio Trust.)

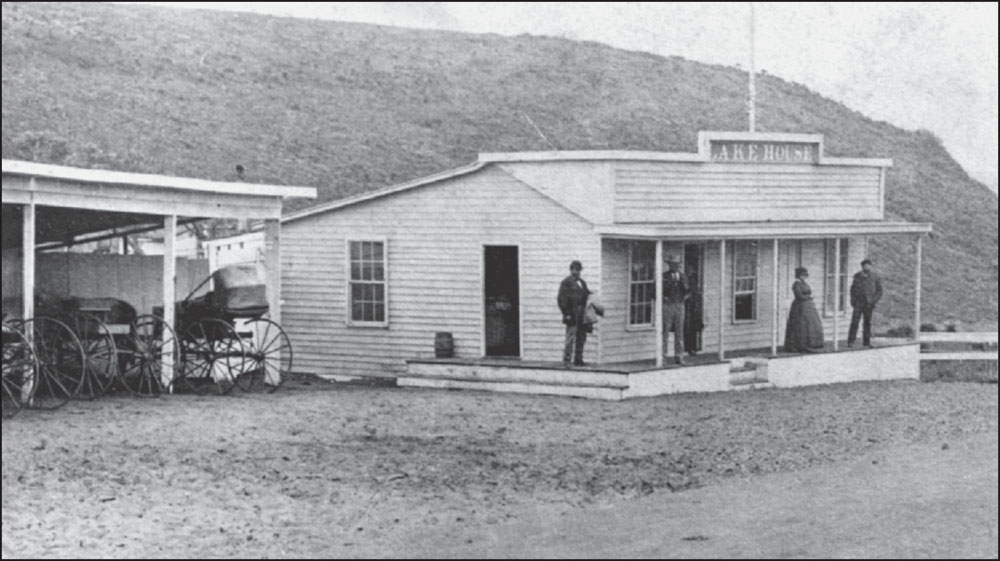

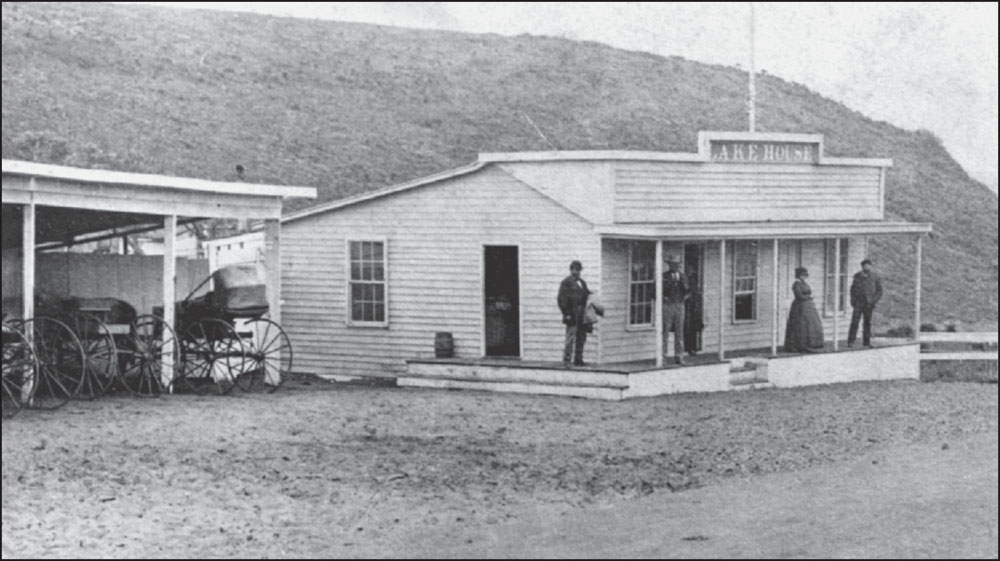

In the 1870s, John Middleton Sr. moved the Lake House, which was to be used as his residence, from Lake Merced to Bryant and Second Streets. This move was likely the longest move on rollers ever undertaken by a San Francisco house. Curiously, there were two lake houses. This photograph’s identification is not definitive, but it most likely shows the earlier residence, which was moved by original owner Don DeHaro’s son-in-law from the south of the lake. (Courtesy of a private collection.)

The lumber for the Schwerin family home was brought from France on three ships and then by wagon to Visitacion Valley, where Henry and Ottilia Schwerin raised eight children. The home was torn down in 1922. During the Gold Rush, there were hardly any men felling lumber. It was hard to get material to build a house, often prompting extraordinary measures. (Courtesy of the Taylor family collection and the Visitacion Valley History Project.)