Five

MOVERS AND SHAKERS

BUILDING MOVES OF THE 1940S–1960S

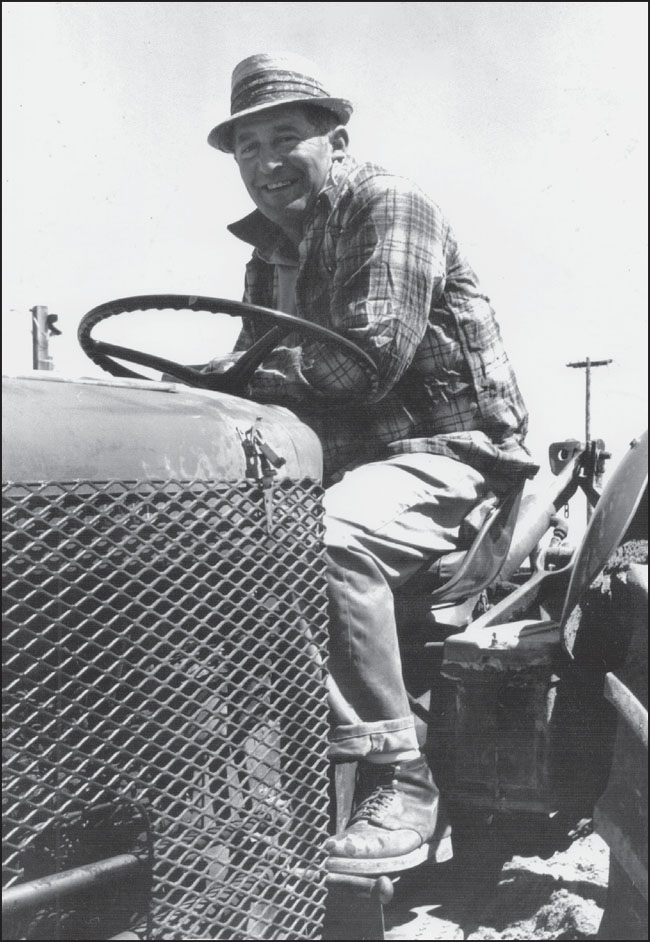

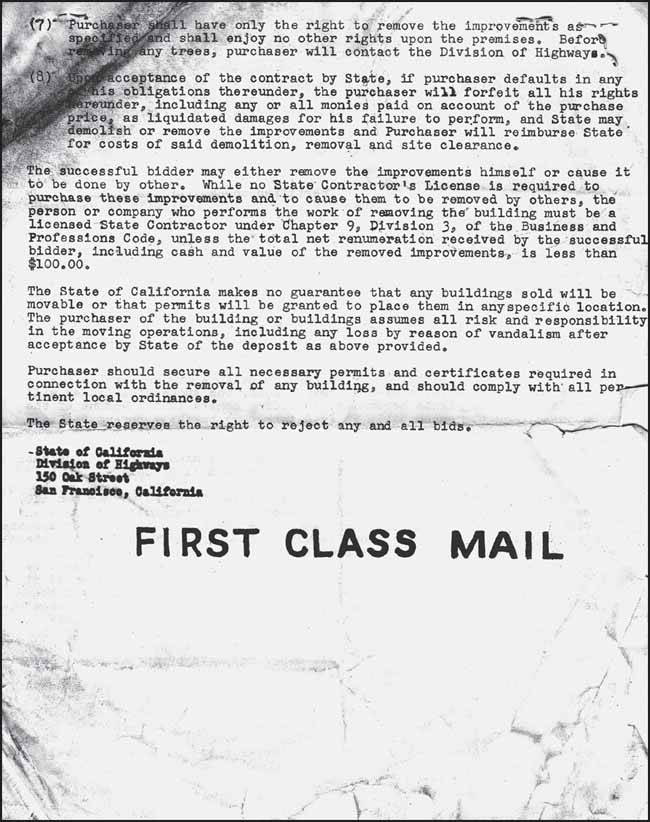

Joseph Caruso, a hardworking Italian American contractor with a big family and a big heart, saw opportunity when the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) system employed eminent domain in the 1960s to inform people that their houses had to be moved or destroyed to make way for progress. His journey from contractor to house mover centered on obtaining cheap houses at auction for $300 to $500, moving them onto his vacant lots, and renting them. Joseph Caruso’s small local Portola District business would change the lives of everyone he touched. Sweeny Street and Gaven Street vacant lots hosted groups of his buildings (as many as nine in one row), with his construction expertise lending to their move, reconstruction, rental, and eventual sale. His willingness to tell a small child stories about his house-moving business was a direct influence on the creation of this history some 40 years later. (Courtesy of the Caruso family collection.)

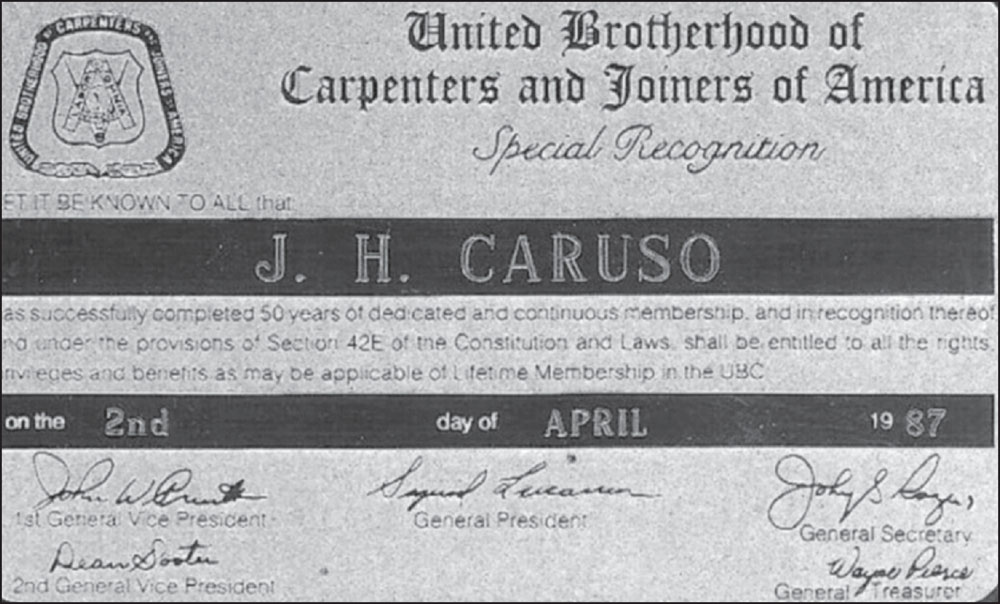

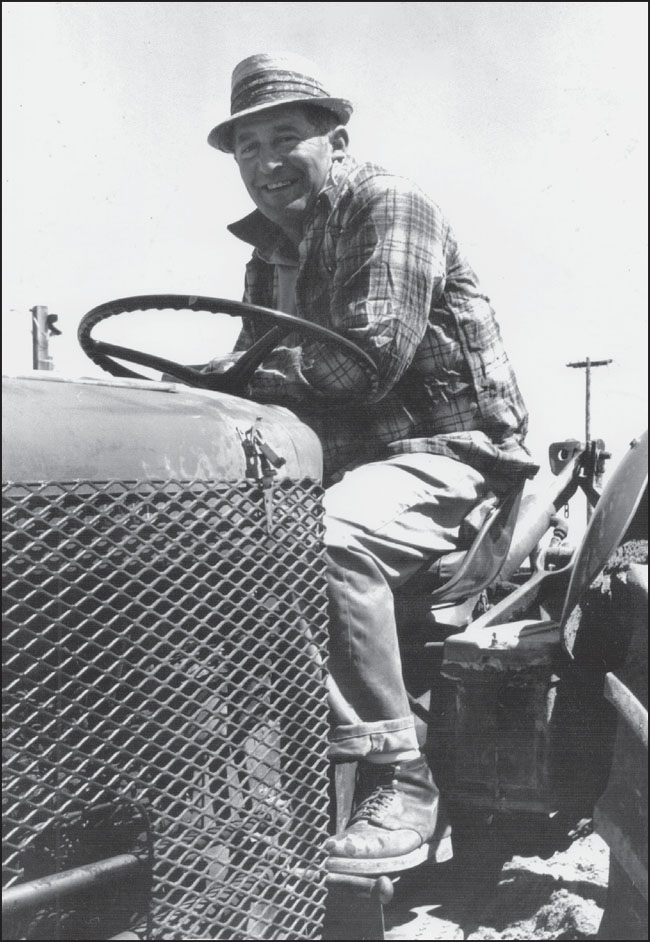

Joseph Caruso’s dedication to his job is recognized in this certificate from the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America. Ten years later, he would receive a pin commending 60 years of achievement. His motivation may have been money, but his side business of moving houses into the neighborhood changed many streets in the Portola District. (Courtesy of the Caruso family collection.)

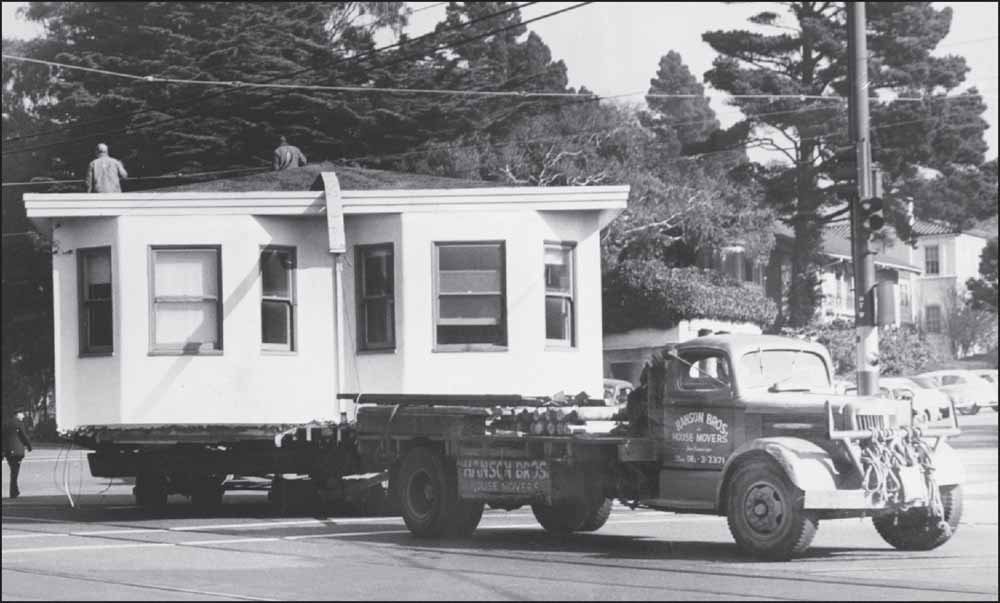

Hanson Movers and Joseph Caruso moved these two row houses (center) from Balboa Park into the Portola District. Caruso’s teenage son Anthony’s job was to ride atop the building, pushing up street wires as the house crept down Silver Avenue. Power and phone lines were guided over the house by inverted skids on the front of the house. Two-by-fours insulated the men from power lines, most of which were frayed or bare. (Photograph by Beni C. Bacon.)

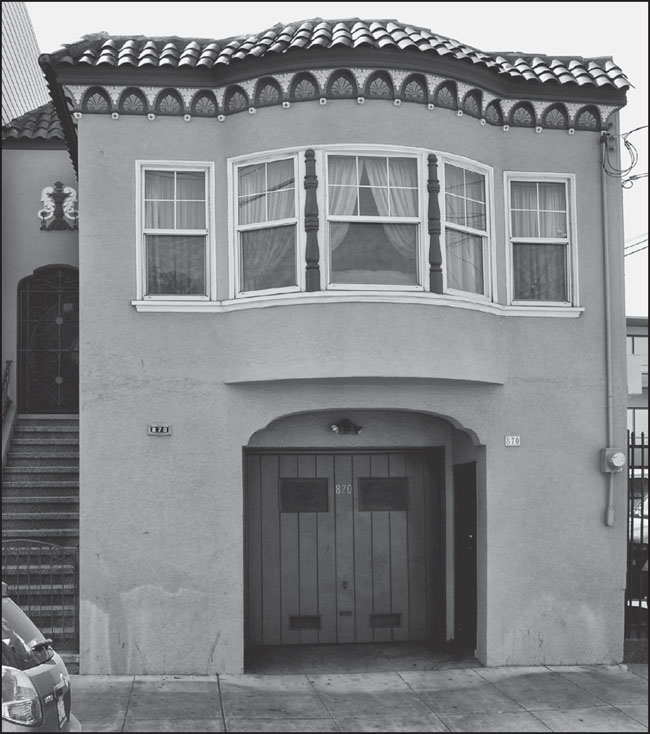

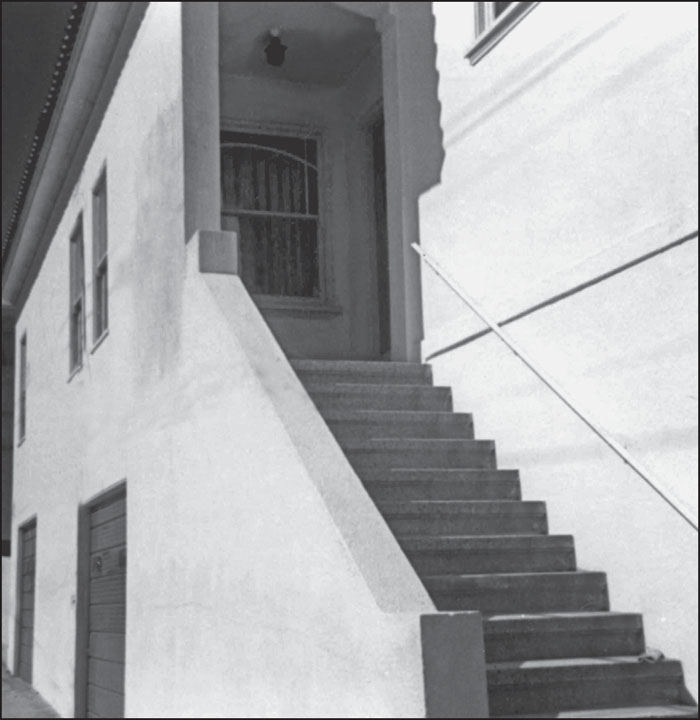

Joseph Caruso’s biggest coup was his purchase of a vacant block of land on Gaven Street. It also proved his greatest challenge, as he then had to subdivide the land into lots, all of which had to be 25 feet. The last oversized lot required him to search the city for a wide home that needed moving and would fit on a 33-foot lot; he finally found such a house at Geneva Avenue and Mission Street. (Photograph by Beni C. Bacon.)

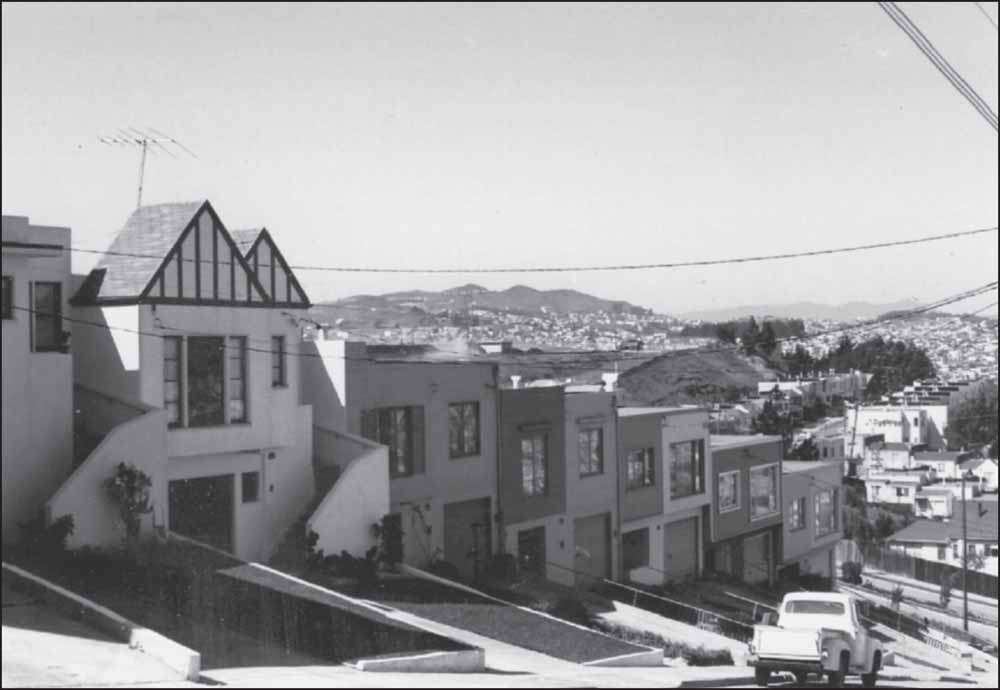

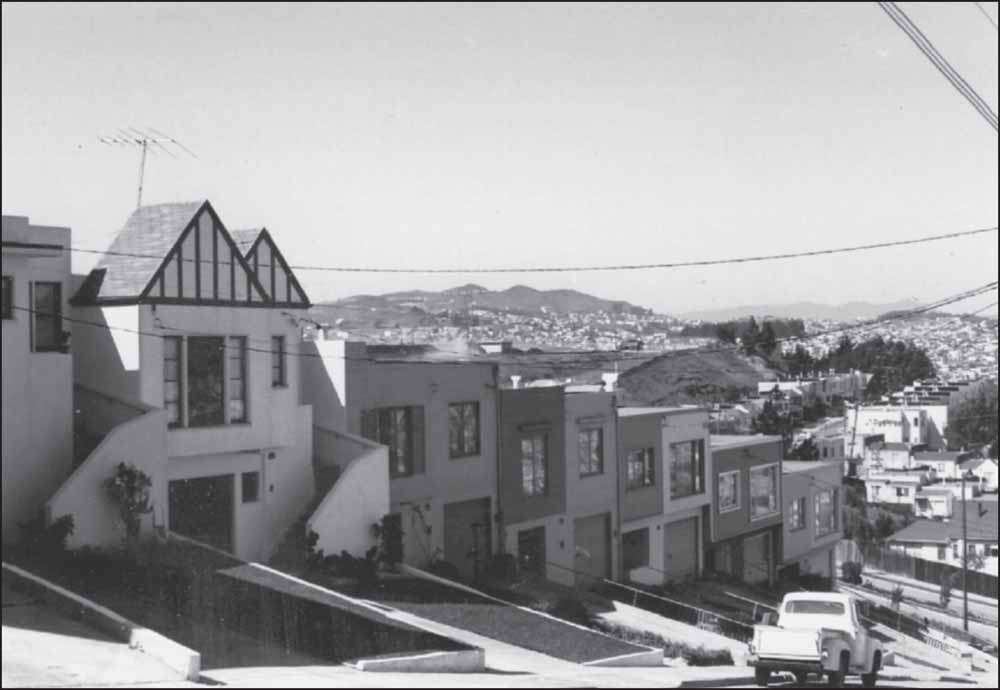

Joseph Caruso moved every house seen in this picture of Gaven Street, one by one. All houses were auctioned due to the BART system’s construction. When Joseph Caruso was ready to sell them after years of renting, $2,000 down would allow even struggling renters to own. He had his own payment books and often financed the purchases himself. (Photograph by Beni C. Bacon.)

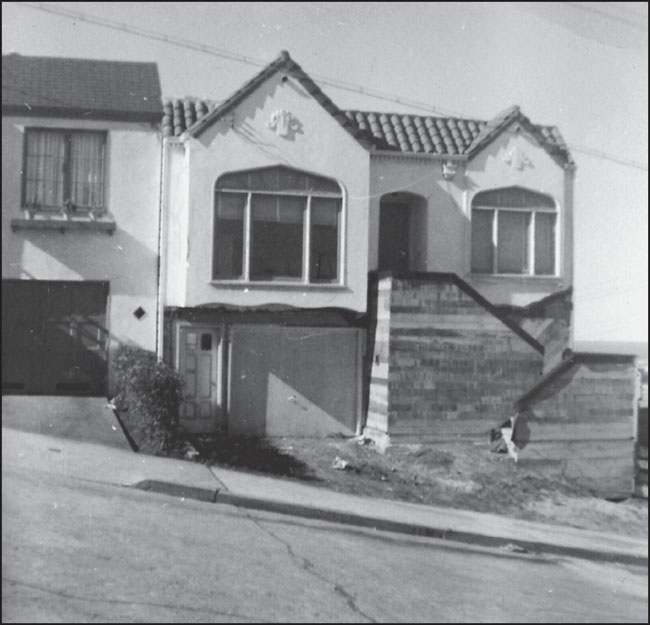

Another of Joseph Caruso’s moved houses resides on the first block of Gaven Street. Its brickwork was added on later. When the owner of the building next door blamed Caruso’s house-moving activities for causing his home’s cracked walls, Joseph Caruso simply bought the disgruntled homeowner’s abode to solve the problem. (Photograph by Beni C. Bacon.)

The two houses on Sweeny Street originated on Arco Street, a tiny dead-end side street located several neighborhoods over in Balboa Park. Note that similar houses sport the same tunnel entrances and phony roof fronts (the newer, shallower houses have tile roofs). After the longer homes were moved, taller ones were built in their place, albeit with much smaller yards due to BART, which tunnels underground behind these buildings. (Photograph by Beni C. Bacon.)

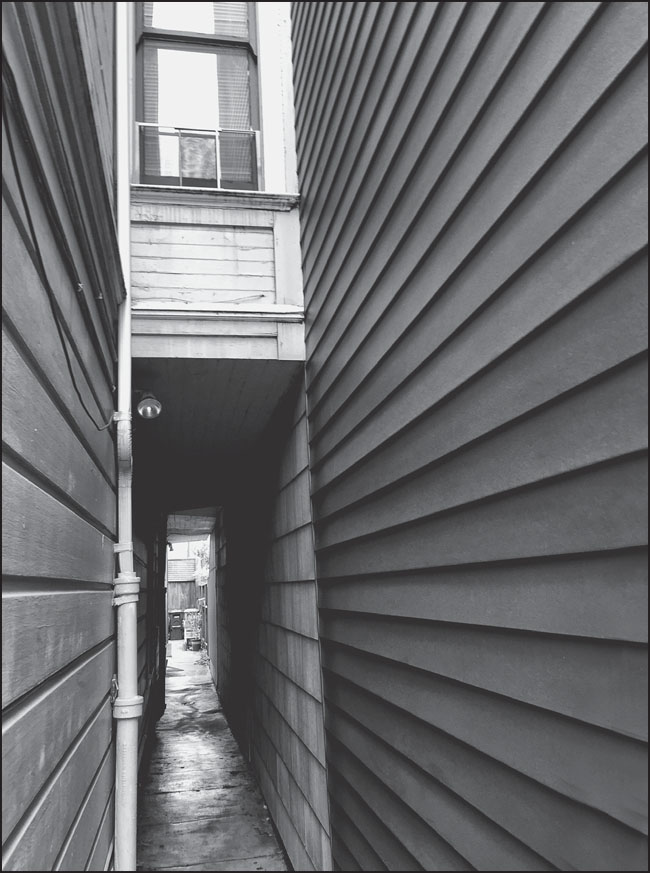

The BART system runs behind this Balboa Park house, which remains next to a vacant lot where one of Joseph Caruso’s houses was moved out. Note that despite its expanse, the side of this remaining house has no windows; one clue that it once abutted another building. The house removed would have been just as long as this home—too long for the BART tunnel angling in behind it. (Photograph by Beni C. Bacon.)

John Kambic was primarily a house builder who constructed a number of homes on San Francisco’s Potrero District between 1919 and 1946. Like Joseph Caruso, he saw opportunity in moving and preserving houses. He passed away in 1972, but his legacy lives on in the form of the many houses he moved out of harm’s way. This photograph shows him as a young man. (Courtesy of the Donald Kambic collection.)

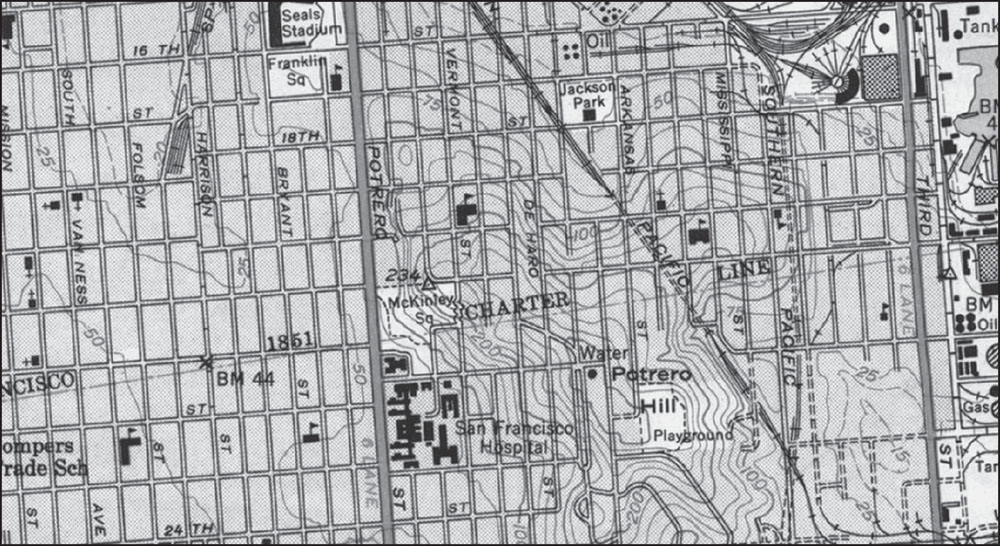

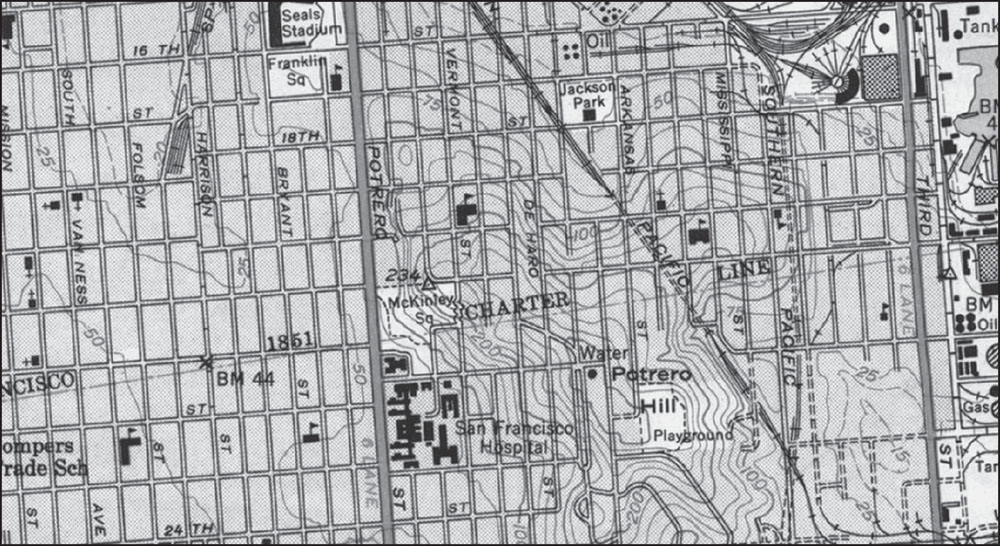

The construction of San Francisco’s freeways and transport systems, from Highway 101 to the 280 Freeway and, later, the BART system, ran through neighborhoods and sparked eminent domain battles as homeowners faced the choice of moving their homes or having them purchased and destroyed. This is a pre-freeway 1947 map of the Potrero District. When the 101 Freeway was built, it cut through the neighborhood, seen here at an angle. (Courtesy of a private collection.)

When the 101 Freeway was built through the neighborhood, John Kambic shifted from building houses to moving houses, and he relocated at least 10 houses between 1945 and 1962. This house, which is 25 feet wide at the front and 65 feet long, was moved from San Bruno Avenue to Missouri Street in 1946. (Courtesy of the Mike Shea collection.)

Moving corner-lot houses typically meant larger buildings; however, in some ways, they tended to be easier moves, in that there was more room on one side. At least a corner house did not have to fit between two other houses; although, the building still had to fit precisely on its new lot. (Courtesy of the Mike Shea collection.)

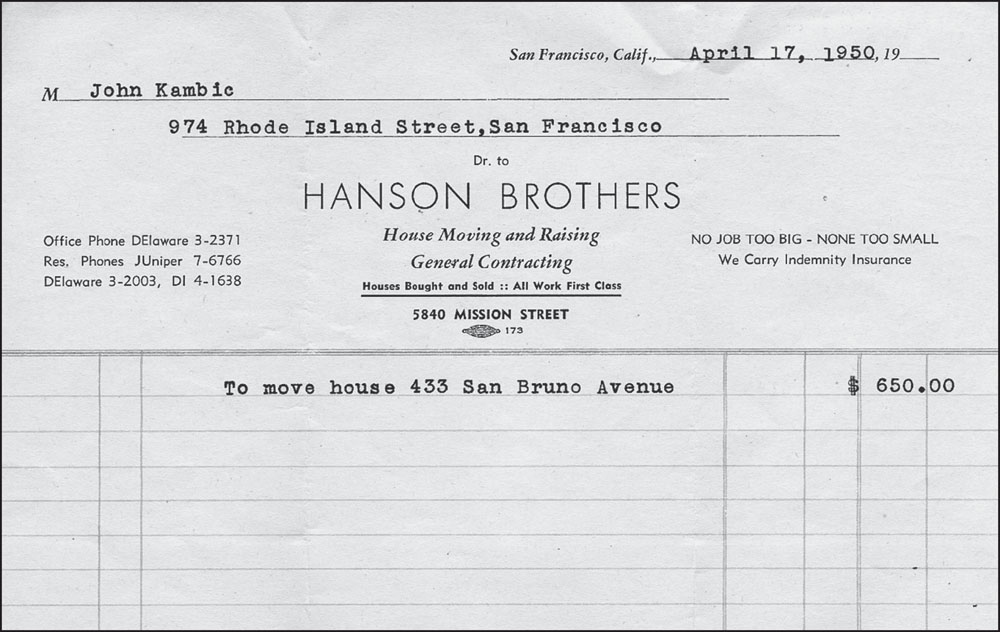

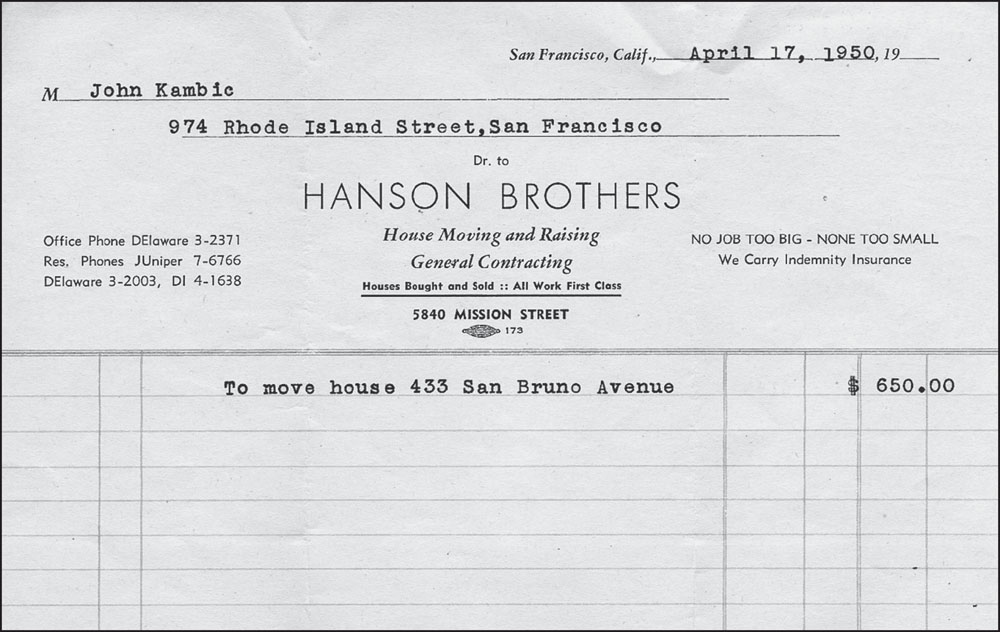

While most small contractors did not move the houses they owned or purchased, they did utilize house-moving companies, none of which remain in the city today. John Kambic used Hanson Brothers for all his moves. This Hanson Brothers Moving receipt documents the cost of a typical row house move in 1950. (Courtesy of the Donald Kambic collection.)

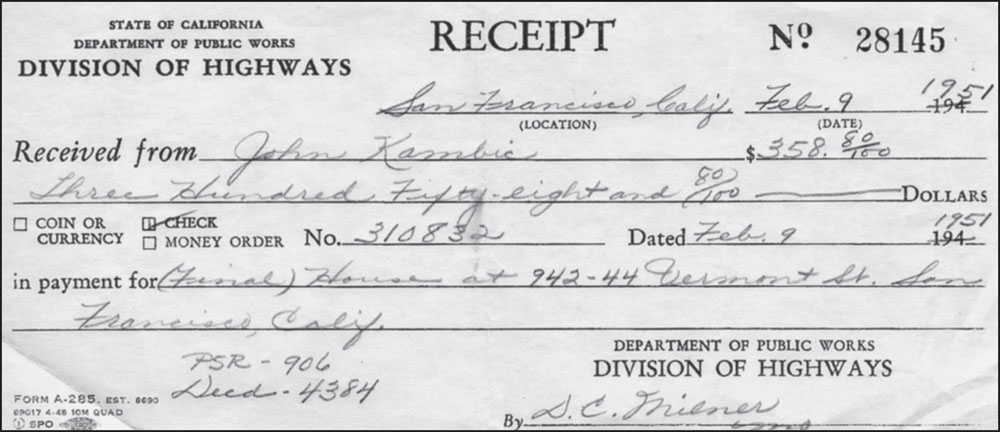

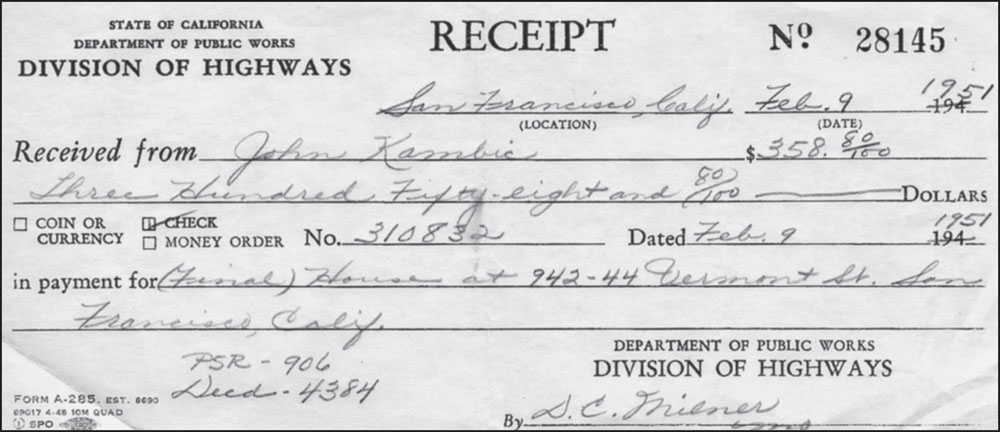

A paper trail follows the process of buying a house at auction and moving it. This is a 1951 receipt documenting contractor John Kambic’s purchase of a Vermont Street house from the Division of Highways. Such houses were typically bid upon at auction and sold for bargain prices because they had to be moved. (Courtesy of the Donald Kambic collection.)

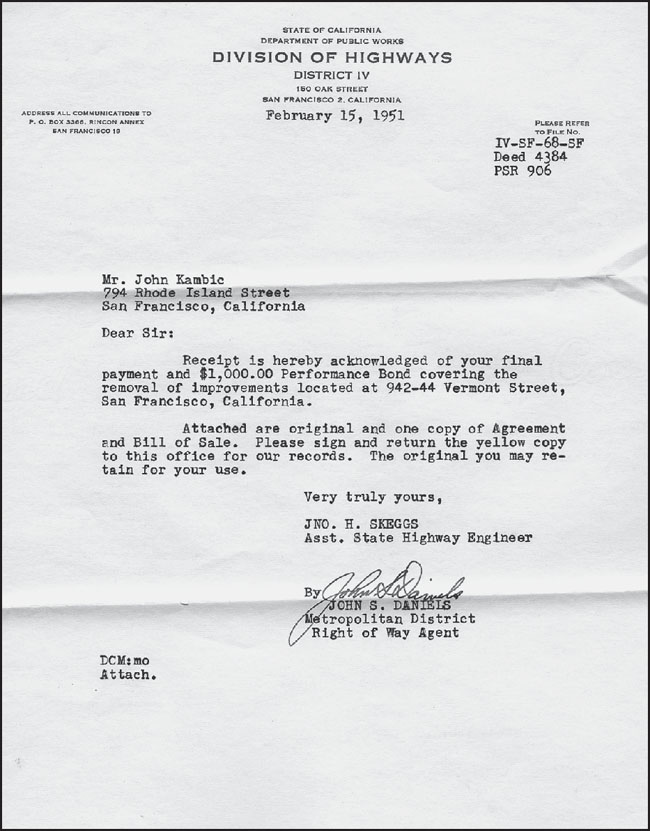

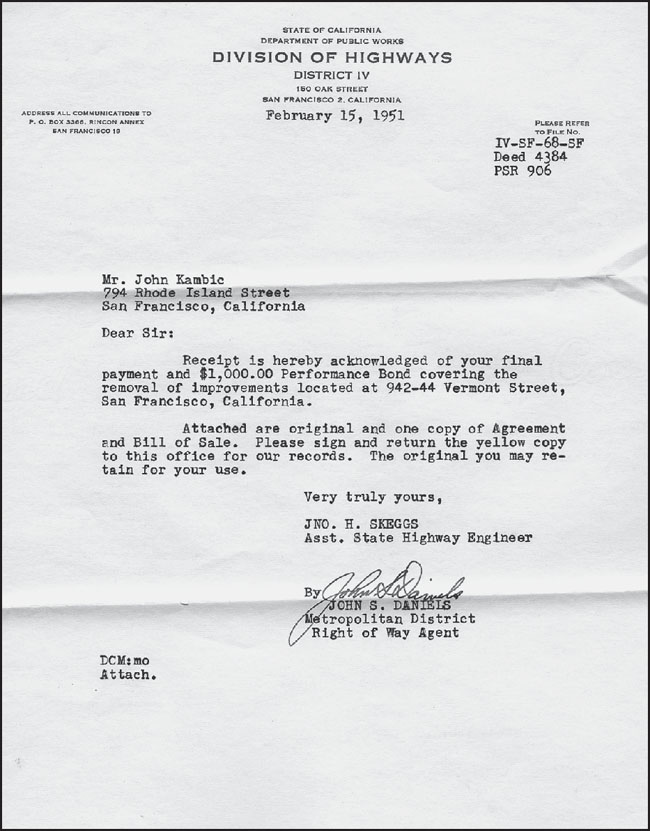

Note the date of February 14, 1951, on this bill of sale and the stipulation in the contract that the house had to be moved on or before April 15, 1951, “down to the ground level,” in accordance with the bid agreement. With only two months leeway, a buyer had to have both the final destination and moving company in place before buying a building at auction. (Courtesy of the Donald Kambic collection.)

With timelines involved in freeway construction, the city could ill afford to sell buildings to individuals who could not fulfill their end of the sale. A performance bond was required of bidders. Here, the Division of Highways acknowledges payment of a $1,000 performance bond by contractor John Kambic—considerably more than the cost of either purchasing or moving the building. (Courtesy of the Donald Kambic collection.)

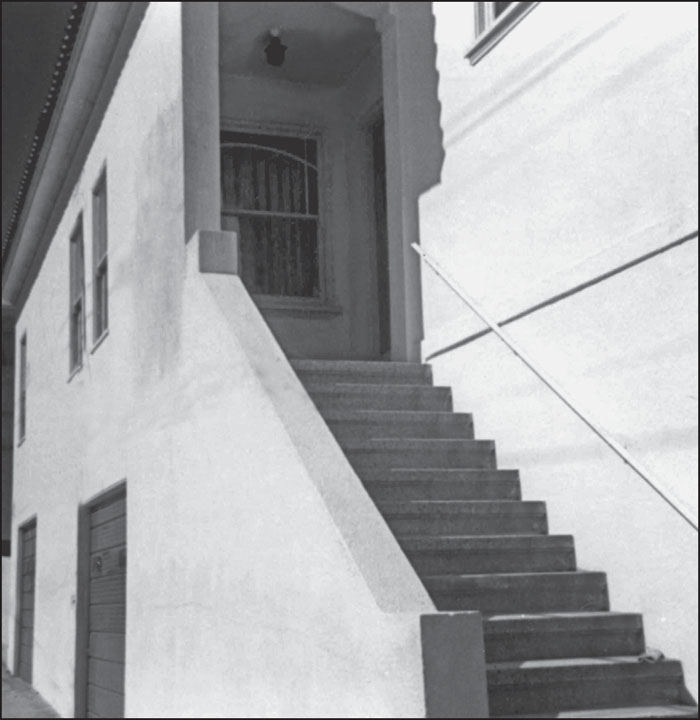

This is another corner-lot house moved by John Kambic. The building, constructed in 1924 on San Bruno Avenue by John Kambic, was moved to Rhode Island Street in 1949. Even though the stairs had to be rebuilt and a new basement constructed, it was still cheaper to buy and move a structure than build one from scratch, especially for contractors who already had the licenses, materials, and knowledge. (Courtesy of the Mike Shea collection.)

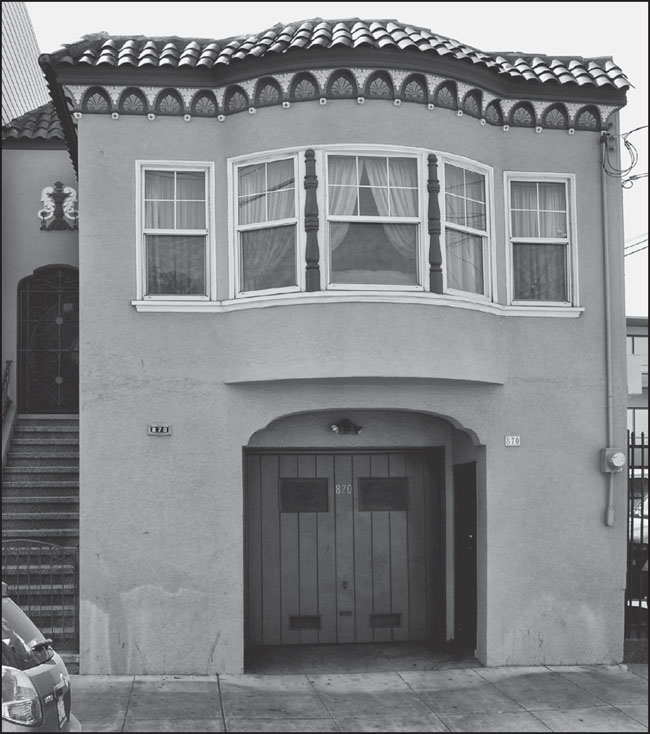

In 1951, this building was moved to Arkansas Street. Its original address is unknown. Note the stucco fronts and similar styles to many of the buildings moved by contractor John Kambic. Such buildings appear in side-by-side rows in many San Francisco neighborhoods. Today, it is impossible to know their origins (or even that they were moved buildings) unless one knows their history. (Courtesy of the Mike Shea collection.)

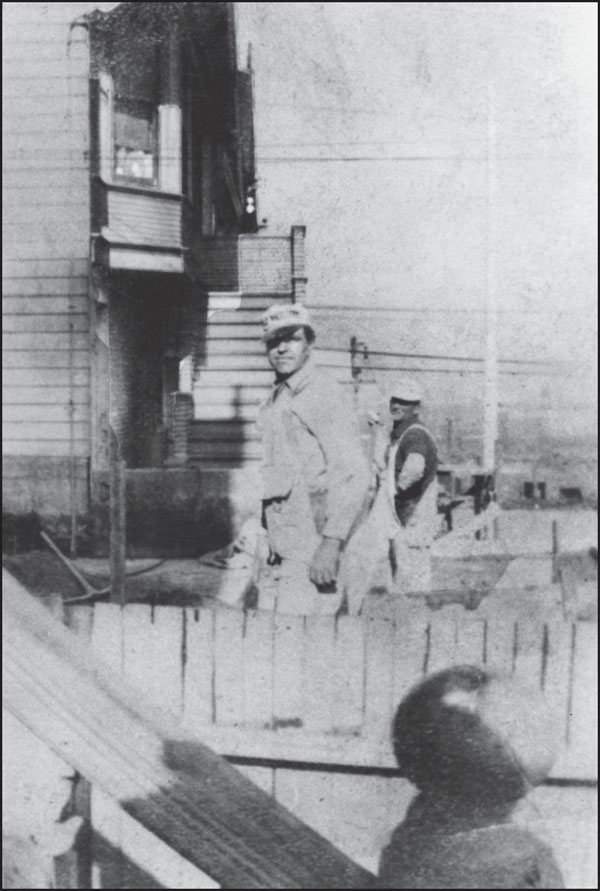

John Kambic is shown building his first house in 1919. Like other small-time contractors who found themselves involved in the house-moving business, John Kambic’s efforts preserved buildings and changed neighborhoods. As both a builder and a contractor, Kambic was familiar with city codes, construction, and the permit process, which enhanced his entry into the house-moving business. (Courtesy of the Donald Kambic collection.)

In 1951, this corner building was moved to Rhode Island Street. It was originally constructed in 1910. Its original location is unknown, but John Kambic’s bid saved this building and added to Potrero Hill’s evolving character. Note that the new corner lot was on a slope, which proved no obstacle to contractor/builder Kambic, who had constructed 14 houses on the steep slopes of Kansas Street. (Courtesy of the Mike Shea collection.)

In 1946, John Kambic moved this building to South Van Ness Avenue. He had built it in 1927 on San Bruno Avenue, as a typical San Francisco row house. Its stucco front was one of his building signatures and was also a popular neighborhood style at the time. (Courtesy of the Mike Shea collection.)

Jim and John’s Place, a neighborhood bar, stood on the left side of Potrero Avenue. In 1933, bar owner and manager John Kambic decided to construct a gas station where the bar stood (501 Potrero Avenue) and build a new, larger bar across the street. Kambic saw a golden opportunity to move a building, but not the whole thing. Take a good, close look at the upper second story of Jim and John’s Place. (Courtesy of the San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.)

The year 1933 was likely when the upper story of Jim and John’s Place moved and became the top floor of a house on Kansas Street. This photograph of the Kansas Street building shows the successful move of an upper floor from one location to another. While San Francisco city records for this address show “year built” as 1933, probably they did not have a category for “moved,” especially not “partially moved.” (Courtesy of the Mike Shea collection.)

Even after taking careful measurements, Kambic struggled to slide one house between two others on Vermont Street. Apparently some of the siding was warped, which made the fit a little too tight. Using bars of soap, John soaped the sides of the house, making it slippery enough to slide into place and rest on top of the new garage walls and foundation. (Courtesy of the Mike Bowman collection.)

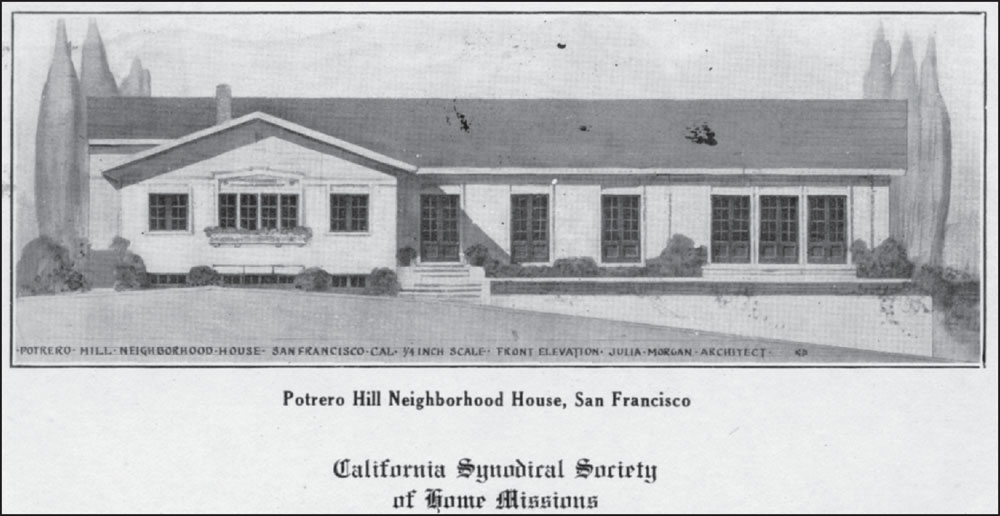

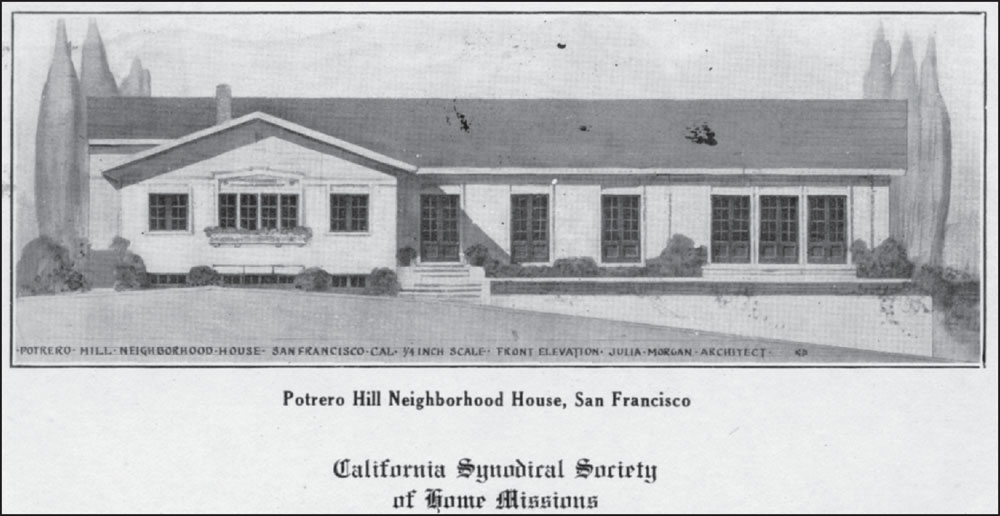

The Potrero Hill Neighborhood House was designed by architect Julia Morgan in 1919, opened in 1922, and was moved to allow for the construction of Southern Heights in 1924. To make way for Diagonal Street, it was situated 90 feet north of its original location to where it stands now, at the corner of DeHaro Street and Southern Heights Avenue. This old drawing shows the building before it was moved. (Courtesy of the Potrero Hill Archives.)

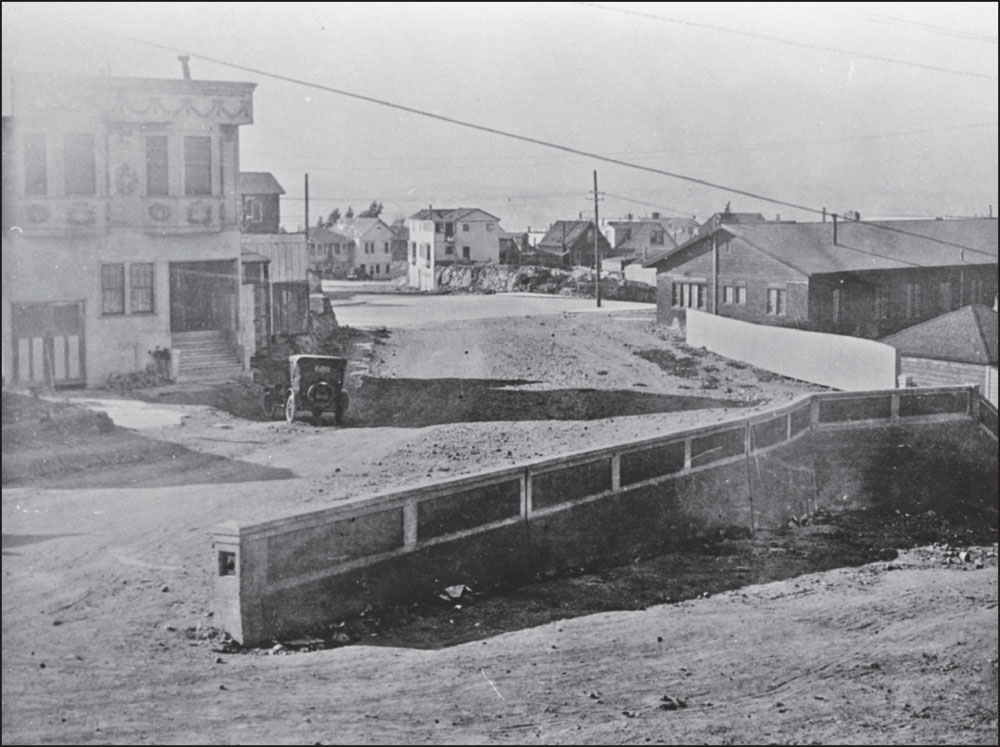

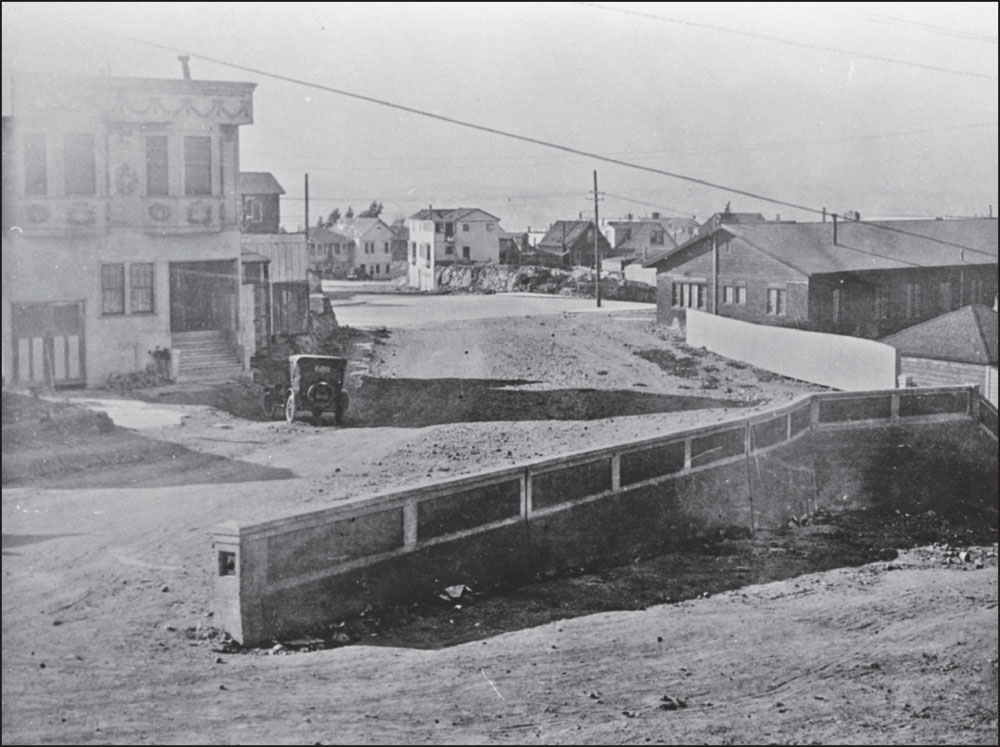

This is a 1924 photograph of the Potrero Hill Neighborhood House just after it was moved. It is the dark building at the right with a pitched roof. It stands in the same spot today, hosting various community groups and sporting a scenic view of San Francisco and the East Bay. (Courtesy of the Potrero Hill Archives.)

In 1950, this three-story, 400-ton apartment building was relocated to Vallejo Street for the Broadway Tunnel’s construction. The 90-foot-long building had to negotiate an eight percent grade. It was set on 120 pneumatic tires and an Army surplus tank carrier, turned on a 60-foot wide street, and backed into a 50-foot wide lot. According to mover Richard Barr Montgomery, one could not stick a piece of tobacco paper between the apartment and the buildings beside it. (Courtesy of the Steve Montgomery collection.)

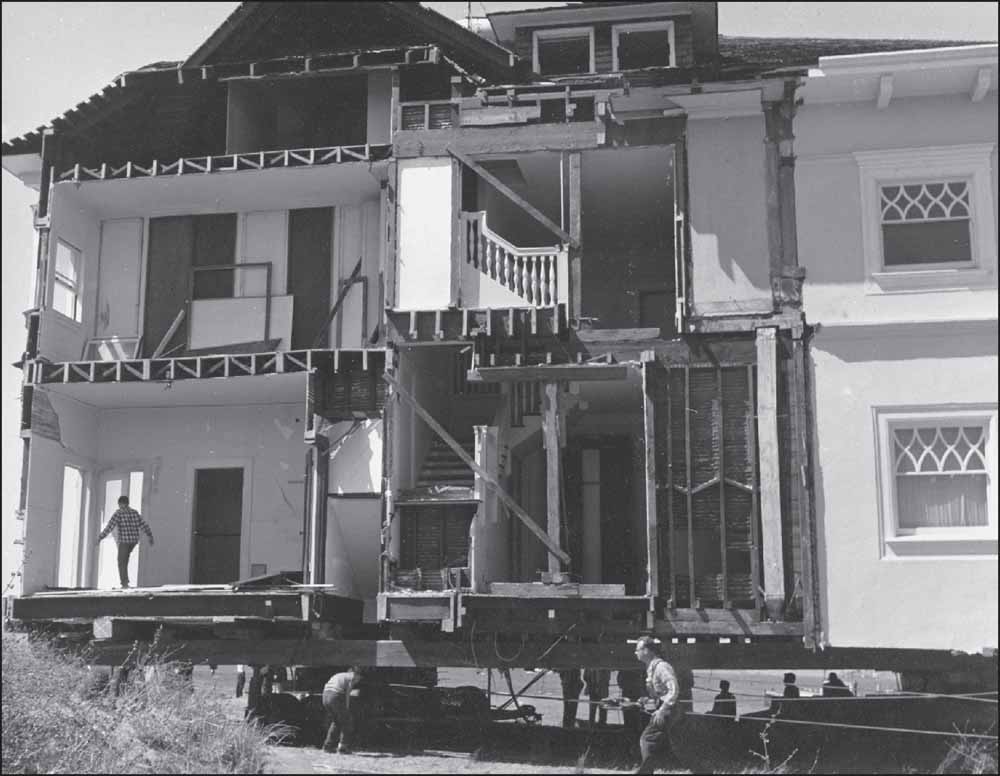

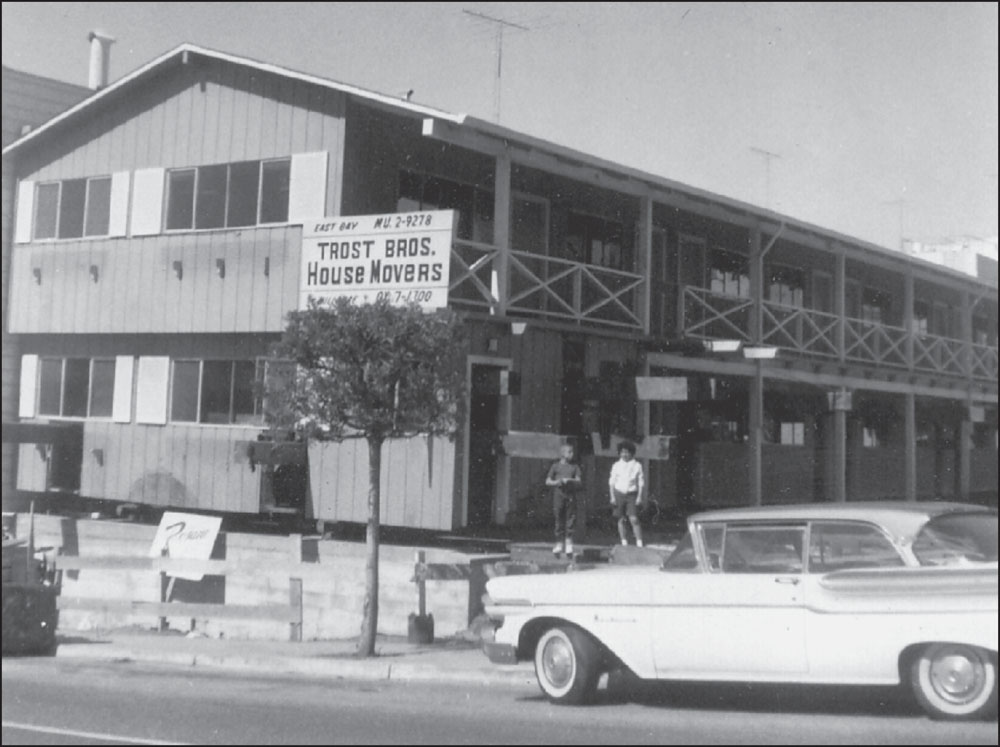

This apartment building was 60 feet wide in back and was constructed to fill its original lot. It was located on San Jose Boulevard and was moved in the late 1950s, when the Bernal Cut was widened. It was the biggest building Hubert Trost ever moved on wheels, traveling two to three blocks to its new home. It was moved in the daytime, down the street and across traffic. (Courtesy of the Hubert Trost collection.)

This picture of a huge apartment building in transit proves that even an oversized building can be moved uphill. The building was jacked high in the air when it was leveled off; it is seen here at an angle. Trost Movers would have to back it uphill to get it placed properly. Note the spectators, who are sensibly standing well behind it. (Courtesy of the Hubert Trost collection.)

One of the remarkable aspects of this particular move was Trost’s challenge of fitting a 110-foot-long apartment building into a sloping lot. Even when viewed from across the street, the venture looks challenging, requiring movers to back the entire building up as well as into an uneven lot. Even today, some longtime residents recall seeing this; it is one of the most amazing moves in San Francisco’s modern building-moving history. (Courtesy of the Hubert Trost collection.)

This image, shot from across the street, provides a better idea of the number of vehicles involved in moving such a massive structure. Blocks were placed behind every truck wheel so that if a cable broke, it would still stop. A beam was placed across the back tires and wedges were driven under them any time the trucks had to stop. (Courtesy of the Hubert Trost collection.)

Perseverance pays off! The building has been pulled entirely onto the lot. The apartment had to be jacked high in the air before it would clear its new foundation. The back end was 60 feet wide. In the 1950s, there were no “pumpers” pouring cement after the building arrived, as is done in modern times. Today, this building has several stories beneath it, which includes parking. (Courtesy of the Hubert Trost collection.)

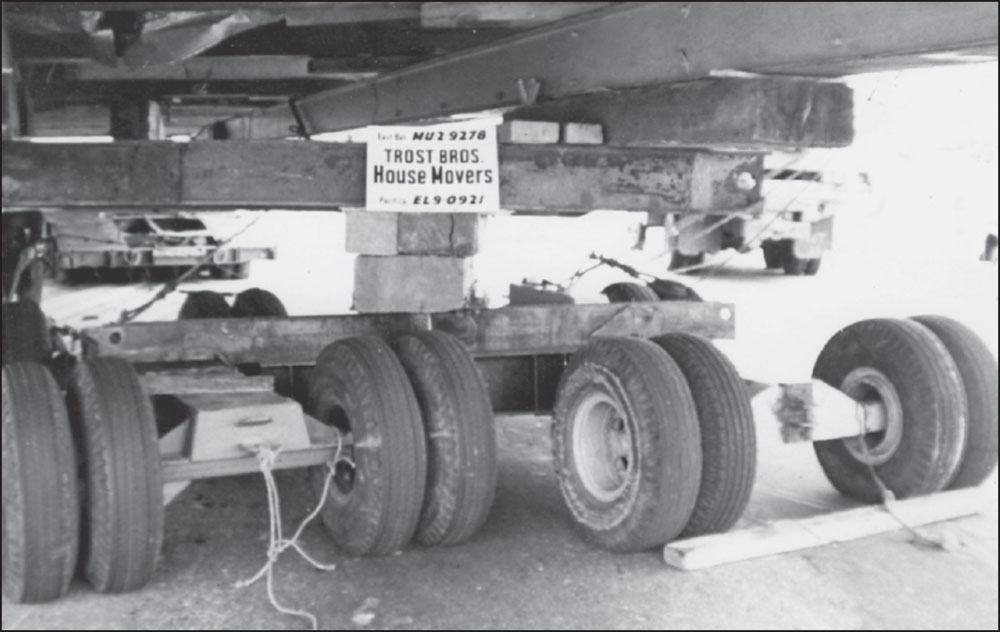

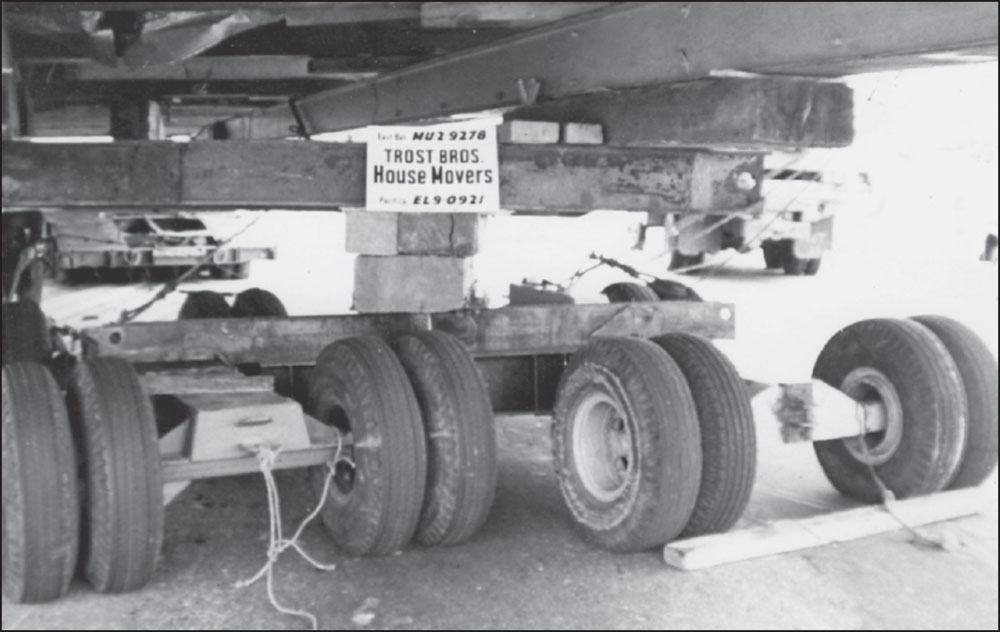

This close-up shot of part of a mover’s truck shows how many tires were on the back axel of the vehicle, alone. Note the block under the back tires. Whenever the structure stopped moving, all the wheels were blocked to assure that the truck stayed in place. As a result of his many precautions, Hubert Trost never experienced a runaway house. (Courtesy of the Hubert Trost collection.)

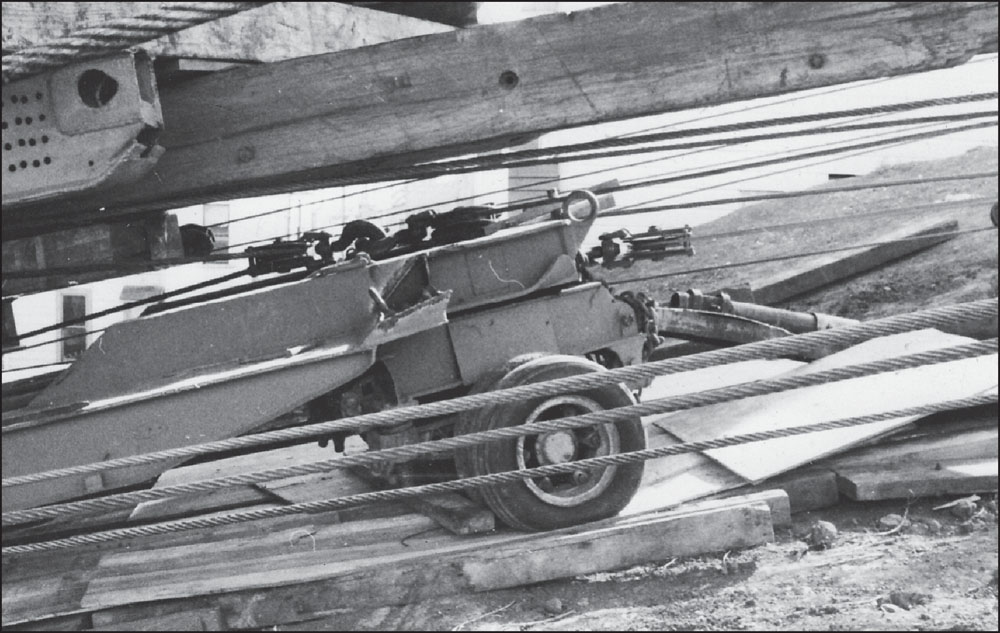

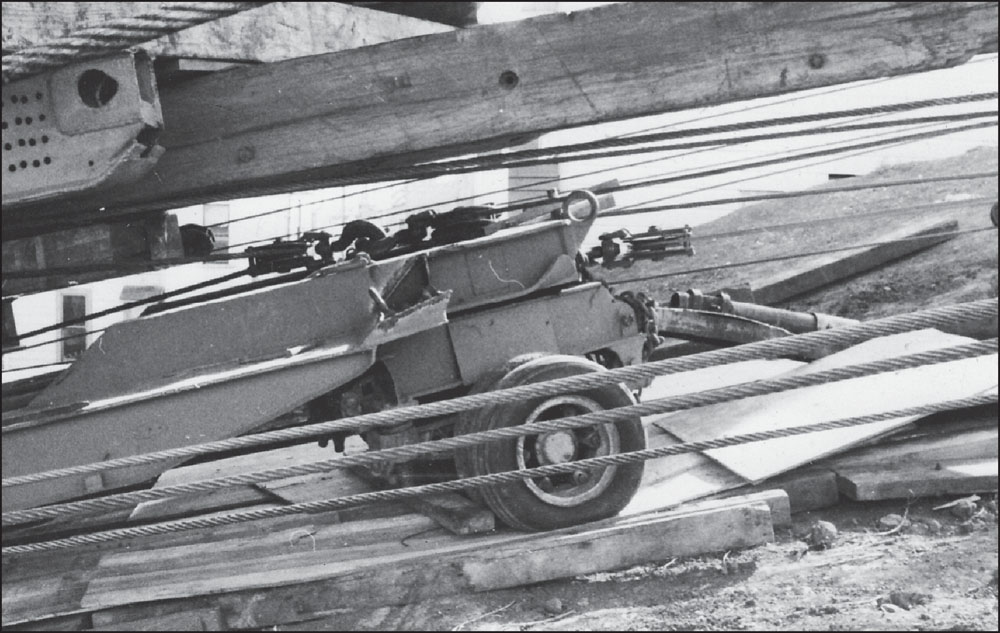

Many cables were used under the building to pull the structure during the course of its move. Trost Movers broke cables twice during this move, so redundancy in placing extra cables was a key to avoiding disaster. The same cables were also used to pull the building up the hill. Trost’s trucks all had winch cable systems. (Courtesy of the Hubert Trost collection.)

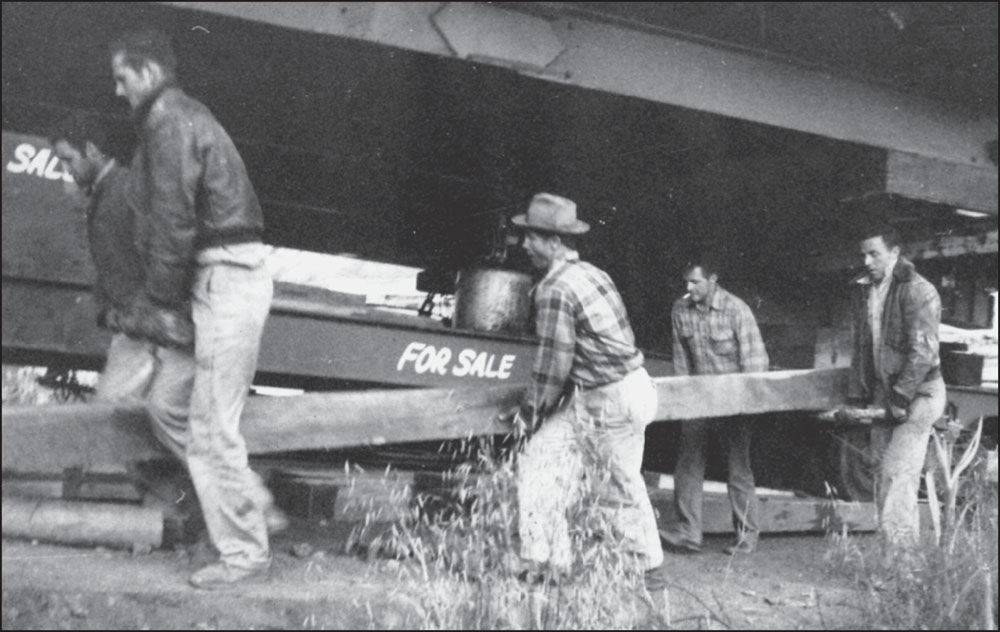

Lumber plays a big role in moving houses, from building cribbing and creating tracks to bracing and wedging truck wheels and serving as skids to help buildings slide during the move. Trost’s workers carry lumber to lay down track, with plywood over it, to make the building’s move smoother. (Courtesy of the Hubert Trost collection.)

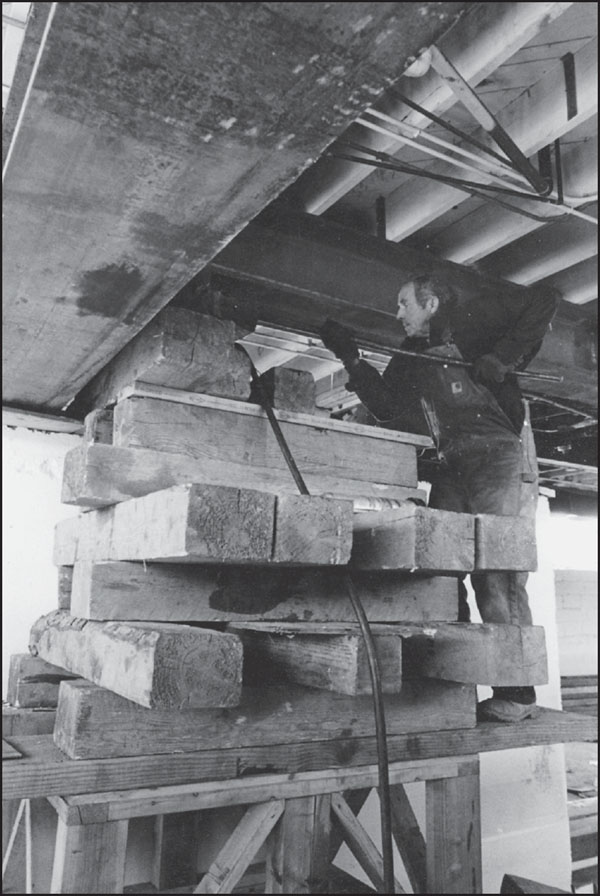

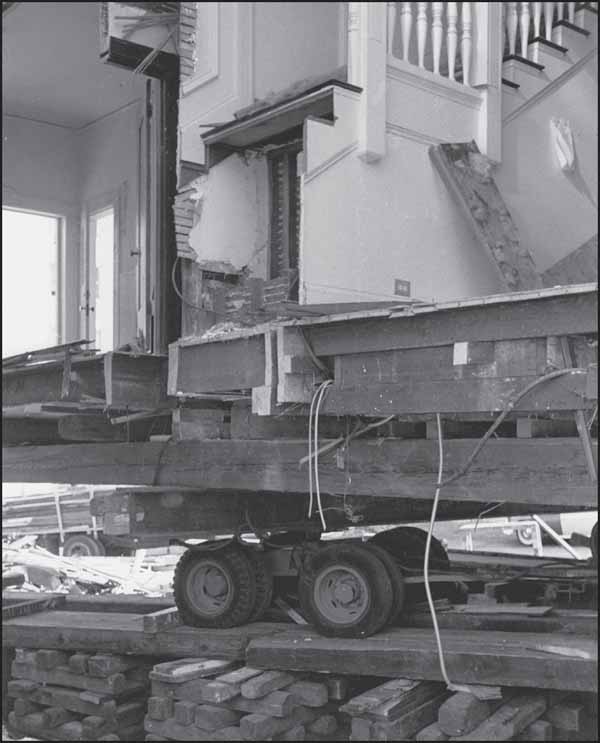

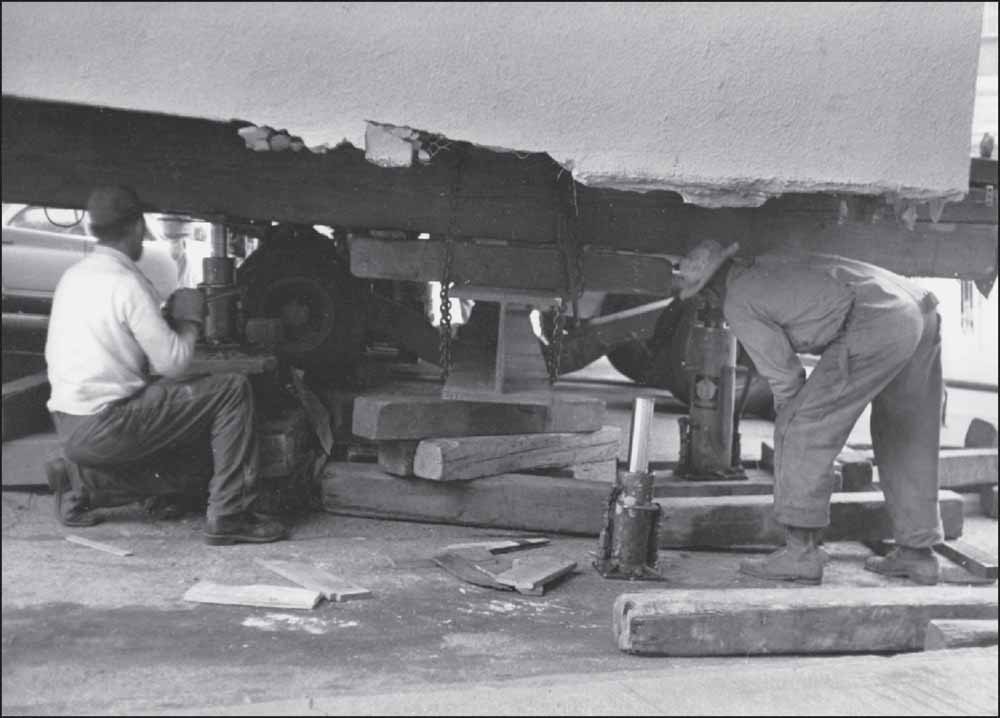

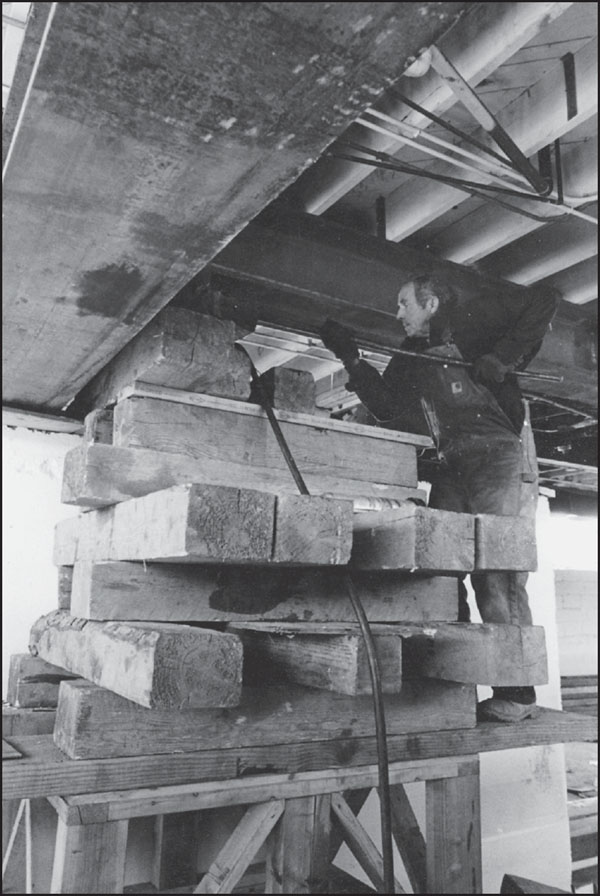

Cribbing is a reliable method of supporting a structure. Buildings need to be raised both before and after moving. Before a move, the structure must be high enough to slide low bed trucks underneath. Once the building arrives at its destination, it has to be high enough to slide over a foundation. The worker here knows that cribbing will keep the structure stable as he works underneath it. (Courtesy of the Hubert Trost collection.)

Not all moves conducted by Hubert Trost involved moves over city streets. A different kind of job involved the Lombard Street Cable Car Motel, which needed to be moved sideways so that another unit could be constructed on the same lot. Building moves that avoided city streets still involved much work. (Courtesy of the Hubert Trost collection.)

Eighty percent of most building moves use the same basic principles and procedures. Here, the long Cable Car Motel is being raised up in the early stages of preparing for its move. The grading work and lot preparations beside it were required before it could move sideways on the lot. (Courtesy of the Hubert Trost collection.)

Now in his 90s, Hubert Trost has been moving houses in California, Alaska, and other states since the late 1940s and still enjoys consulting on building moves. His experience led to his being called out of retirement to oversee the Western Addition Victorian house moves. In this photograph, the author reviews Trost’s vast collection of photographs documenting his historic building moves while listening to his stories. (Photograph by Beni C. Bacon.)

In 1962, architect Norman Gilroy rejected the notion that San Francisco’s historic buildings should be sacrificed in the name of progress. 1818 Broadway, a mansion that Willis Polk designed for Dr. Francis Moffitt in 1914, was slated to be razed for an apartment complex. Its owners agreed to sell Gilroy the mansion (shown here at its original locale) if he moved it off the site. (Courtesy of the Norman Gilroy collection.)

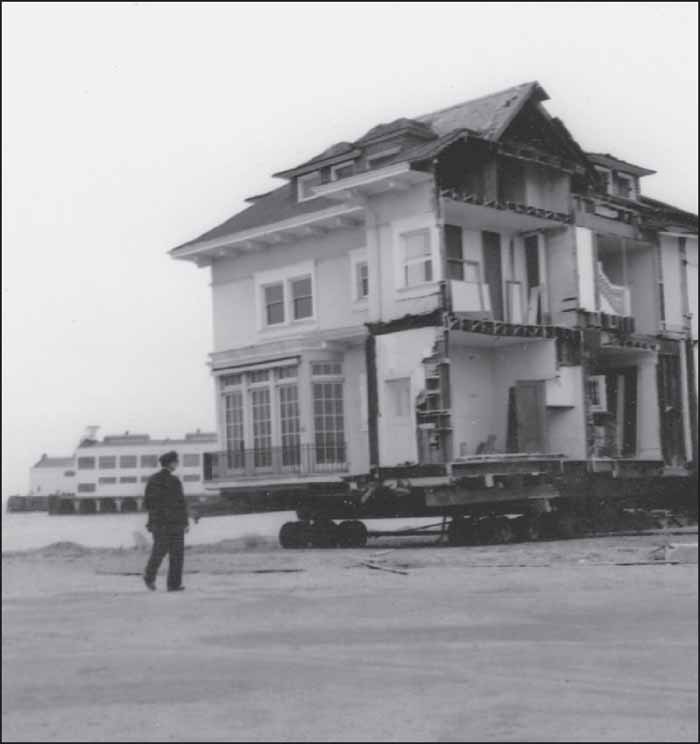

After several months of negotiating for financing and for building and transportation permits at both ends of the move, Moffitt Mansion was ready to journey to the property of some partners on Belvedere Island, which was 15 land and sea miles away across the bay. Using a chainsaw, workers literally sliced the 15-room mansion into two neat sections, each 30 feet high, 35 by 40 feet on plan, and weighing 85–100 tons. (Photograph by J.R. Wilson, courtesy of the Norman Gilroy collection.)

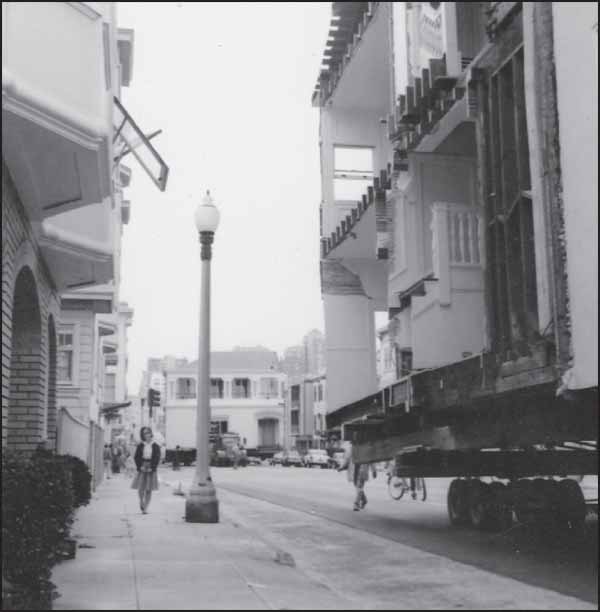

This half of a house is ready to go! Ayen Movers claims this was the “largest and most complicated moving job ever attempted in San Francisco.” It required 30-foot-vertical street clearances, navigating a 2.5-mile route through a congested area, and an elevation drop of 185 feet. Completed at night to avoid disrupting traffic, the move required lowering live transit and power lines at several major street intersections to allow the sections to pass. (Photograph by J.R. Wilson, courtesy of the Norman Gilroy collection.)

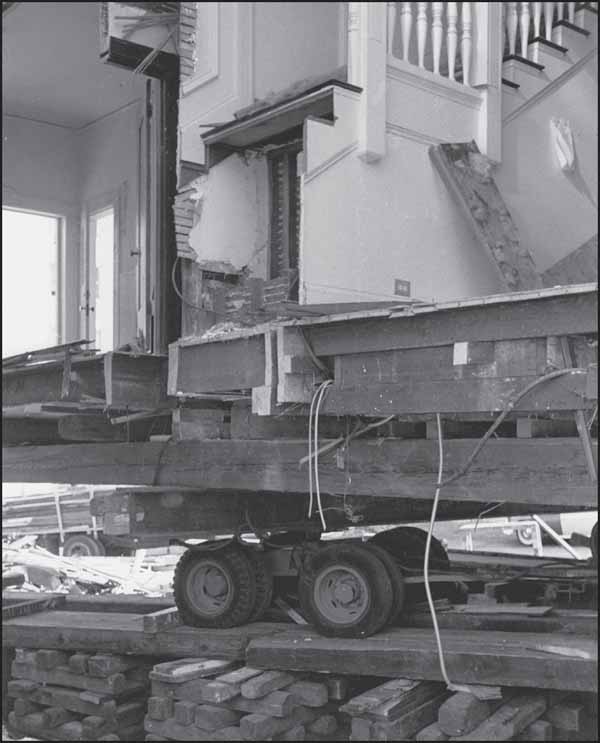

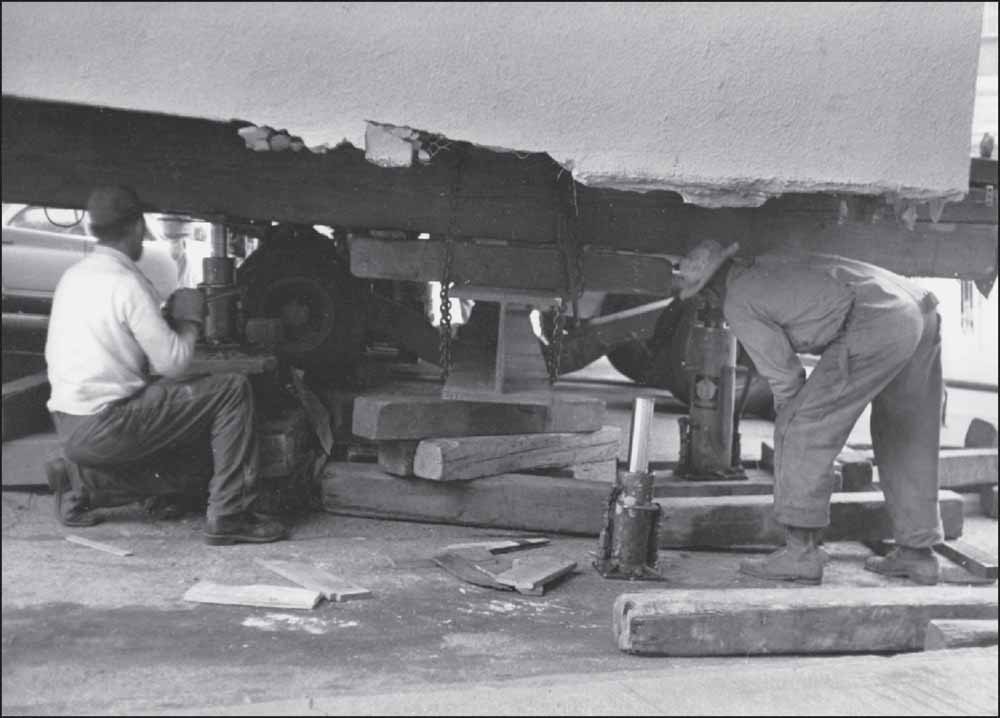

“If you hear this particular whistle, don’t think: just run,” the foreman warned. As the first house section moved onto the steep Franklin Street hill, its full weight suddenly canted onto its front dolly. With a scream like a train whistle, the impact tore a one-inch steel box beam in two, knocking a two-foot hole in the street. Movers scattered like rabbits. Here, workers jack the house up at 3:30 a.m. (Photograph by J.R. Wilson, courtesy of the Norman Gilroy collection.)

Facing a 6:00 a.m. deadline to raise the Muni Transit lines or incur significant penalties, Ayen Movers’ solution was a “bull wagon” driven by a jaunty volunteer. With 85 tons of house hovering behind him, he piloted his load down seven steep blocks of Franklin Street, playing chicken with cars at every intersection. The photograph shows the section loaded onto an Ayen truck. It made it with just minutes to spare. (Photograph by J.R. Wilson, courtesy of the Norman Gilroy collection.)

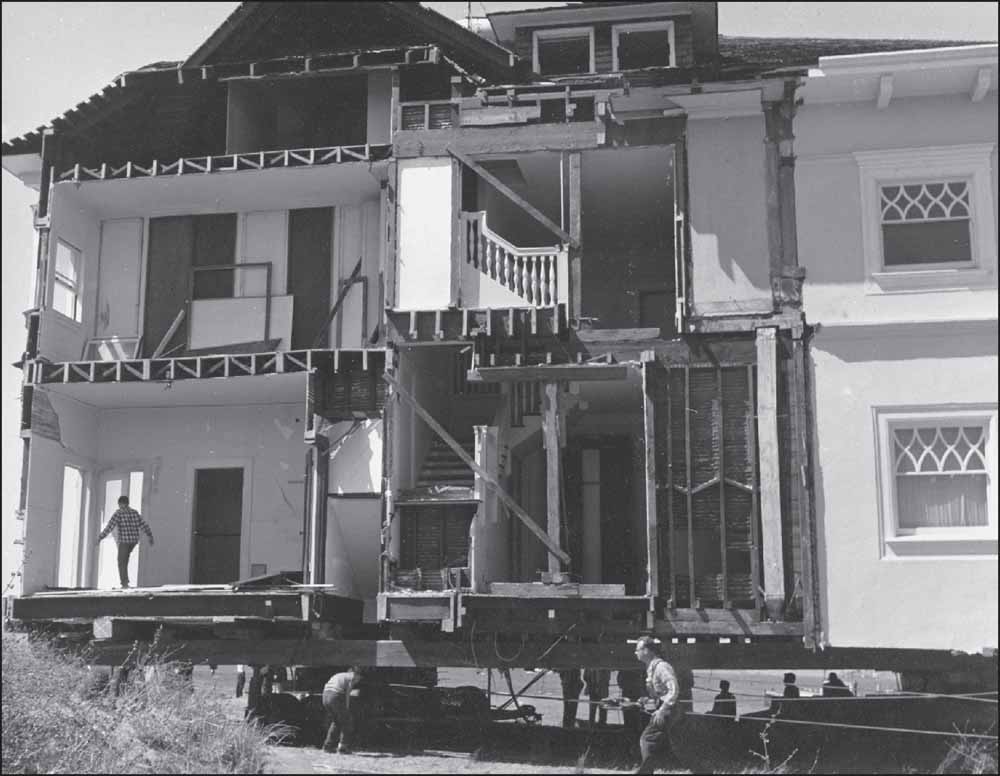

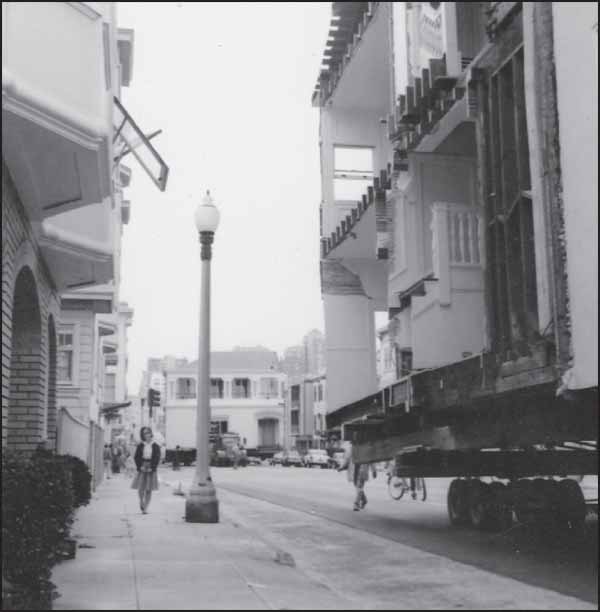

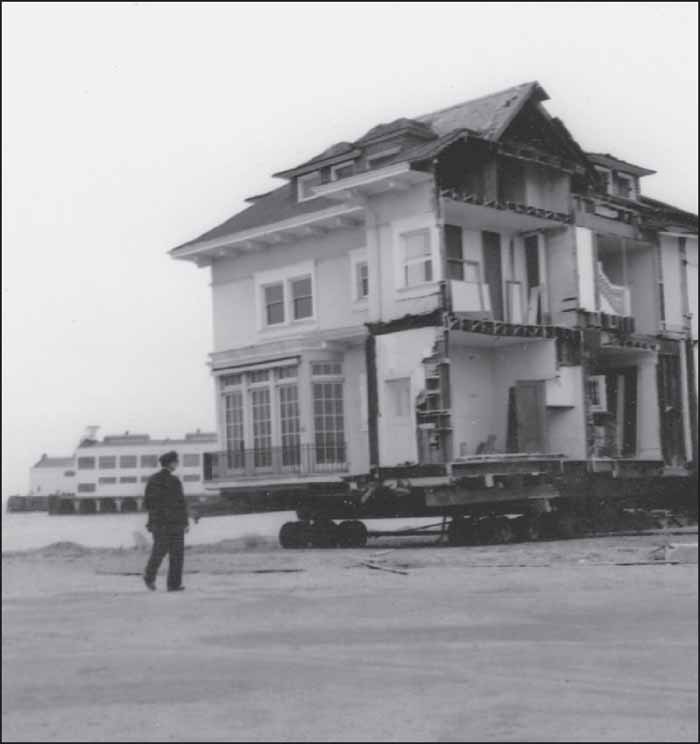

It must have been quite a sight for San Francisco residents to wake up that morning and see two halves of a gigantic mansion rolling along one of the city’s busiest streets, just outside their windows. This photograph shows the two sections on the move, with a curious bystander walking alongside observing the cutaway half of the building. (Photograph by J.R. Wilson, courtesy of the Norman Gilroy collection.)

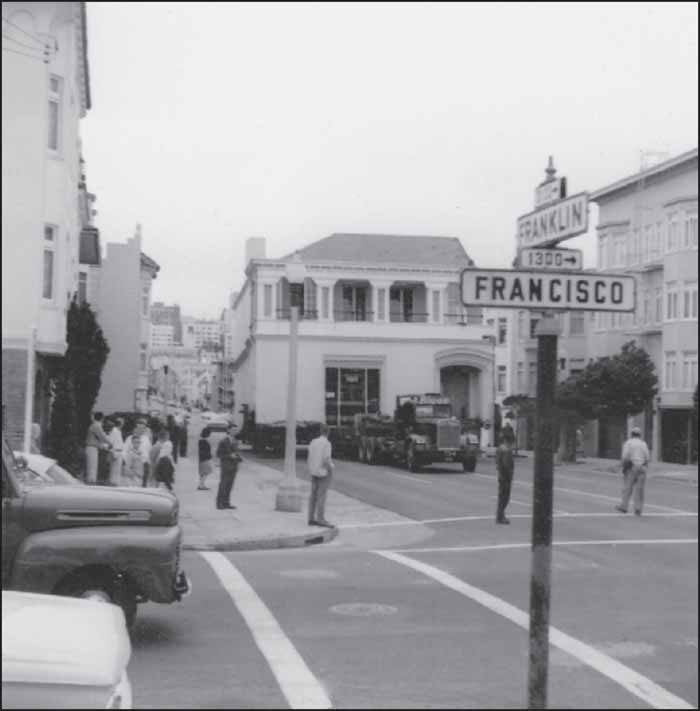

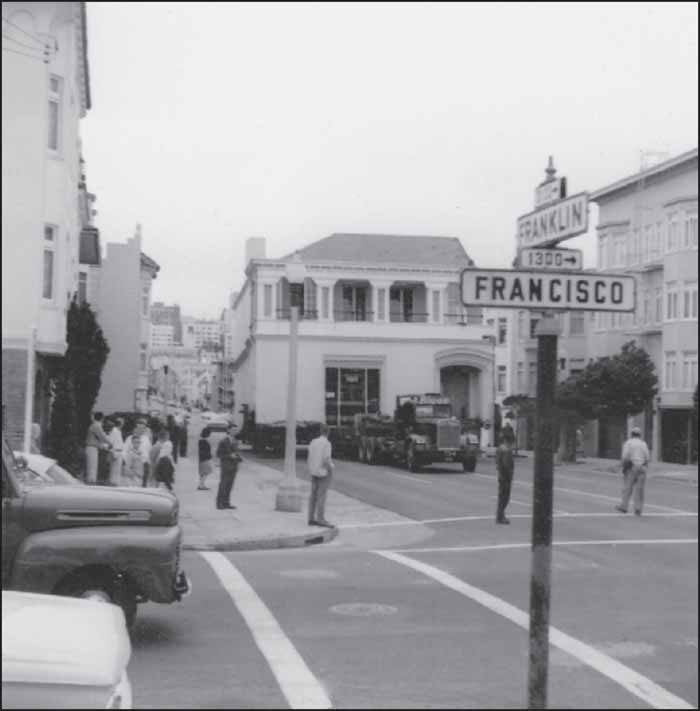

The Moffitt Mansion is shown passing Franklin and Francisco Streets and nearing the place on the Marina Green where it would await transfer to the barge that would take it to its new home. The move was completed by about 9:00 a.m. on moving day, June 25, 1962. (Photograph by J.R. Wilson, courtesy of the Norman Gilroy collection.)

While it waited for the right conditions of tide and weather, the “house on the move” became the subject of much speculation in San Francisco. Even Herb Caen contributed columns and dedicated poetry to the house. But a sad note came when vandals made off with marble fireplaces, carved pilasters, and anything else they could lay hands on. A Pinkerton guard, hired to provide 24/7 security, is shown in the picture. (Photograph by J.R. Wilson, courtesy of the Norman Gilroy collection.)

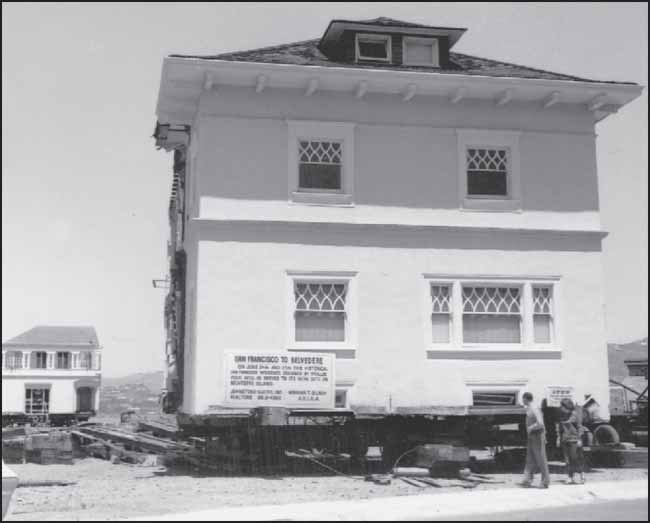

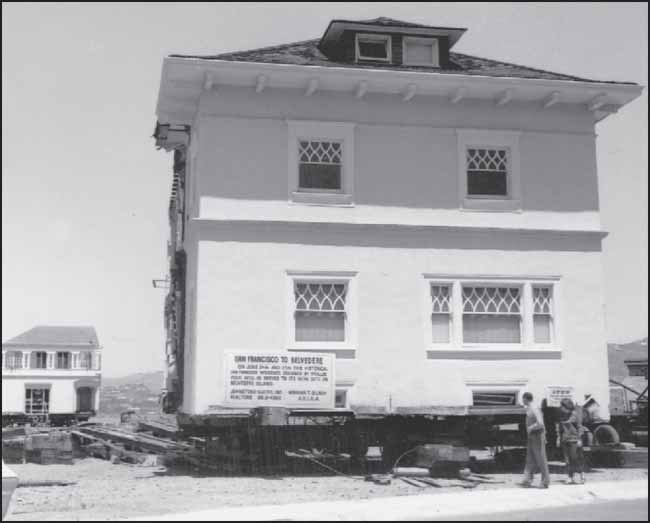

The time spent waiting for the right weather condition was not wasted. This photograph shows the two sections being weatherproofed for their sea journey. Meanwhile, temporary tracks and a ramp were being built to slide the building halves over the seawall onto the barge for transport. In this photograph, the sections of the building have been raised, ready for loading, while a sign indicates their imminent move to Belvedere, across the water. (Photograph by J.R. Wilson, courtesy of the Norman Gilroy collection.)

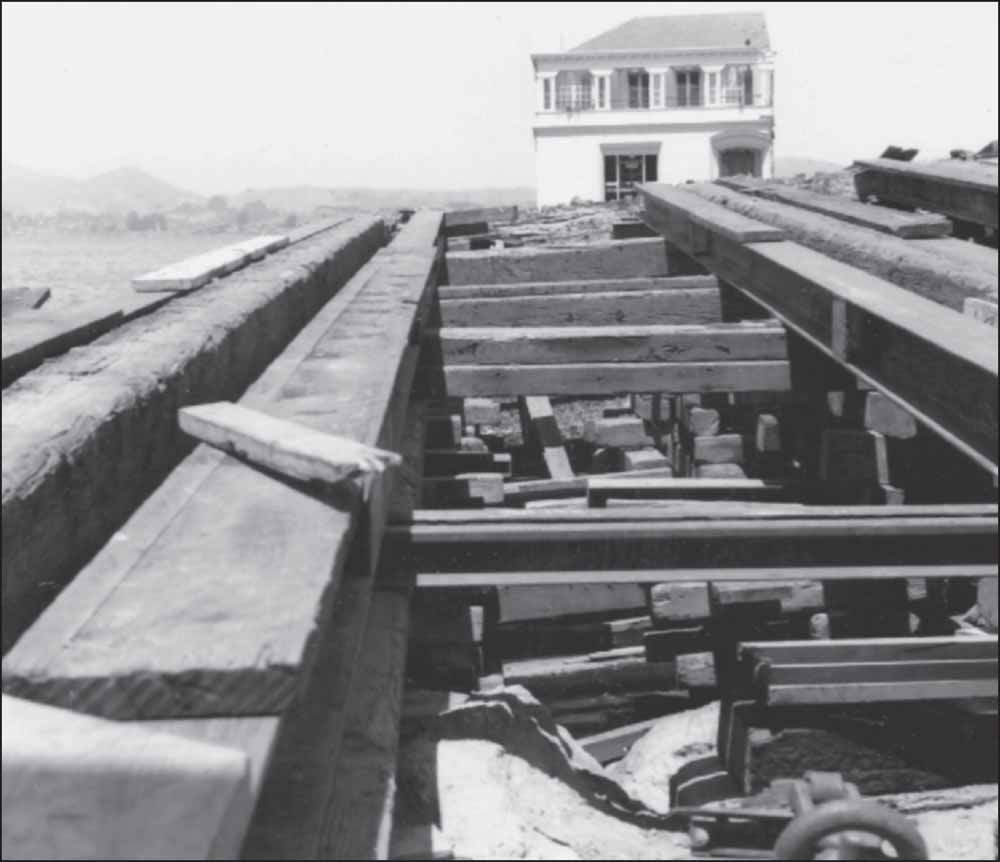

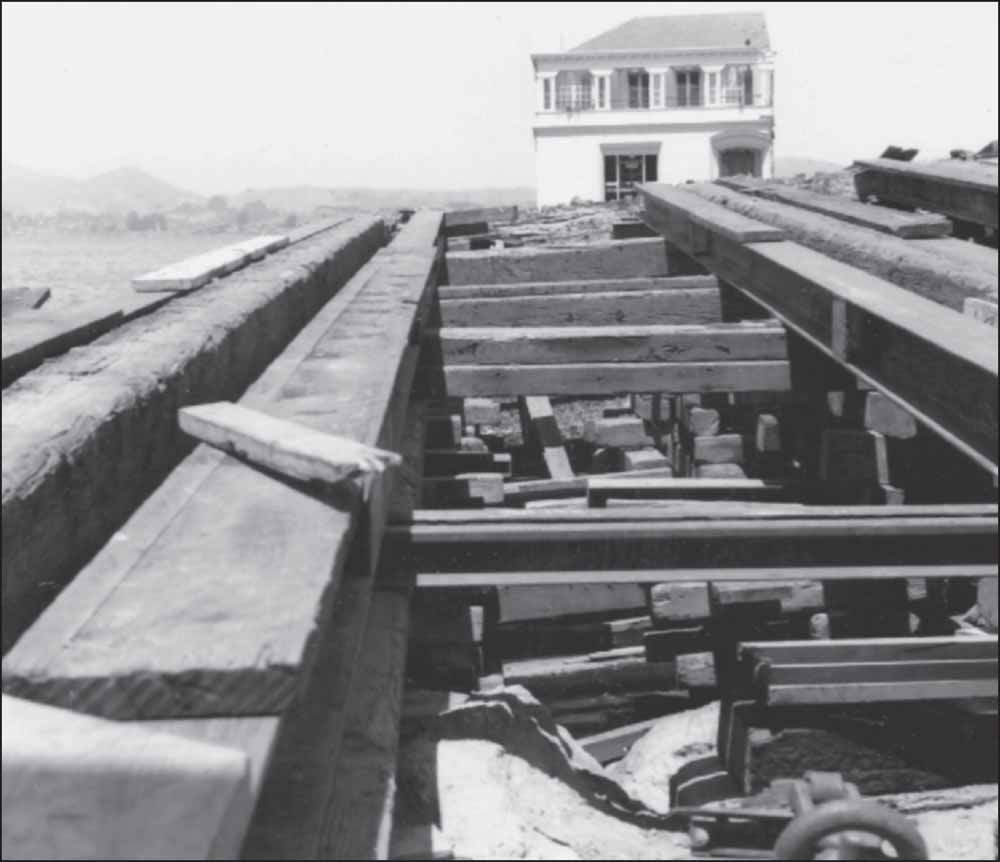

A close-up shot of the track to the barge shows the amount of work and detail that went into building the ramp to slide the buildings from land to barge. A similar ramp for unloading was later built on the other side of the bay. With one of the halves of the Moffitt Mansion in the distance, it is easy to appreciate the immense size and scope of the project. (Photograph by J.R. Wilson, courtesy of the Norman Gilroy collection.)

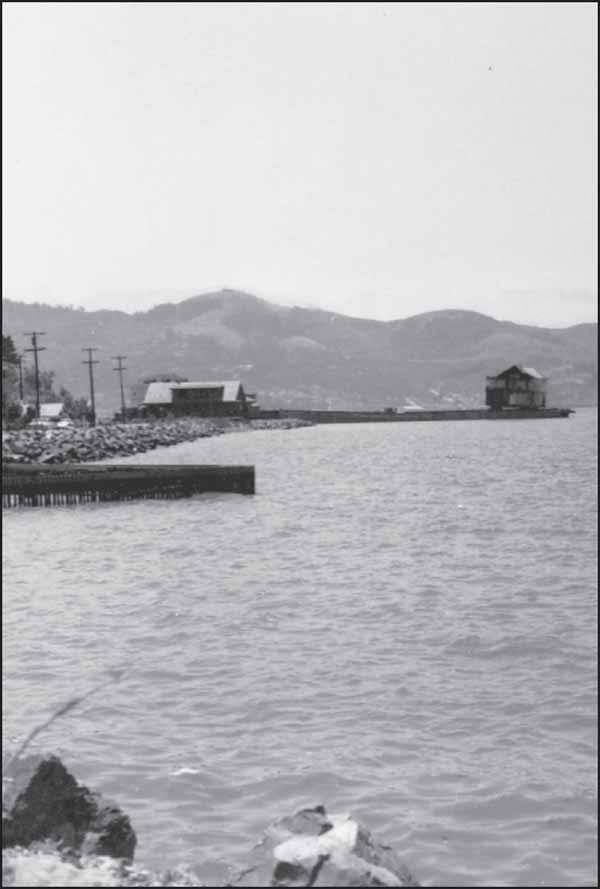

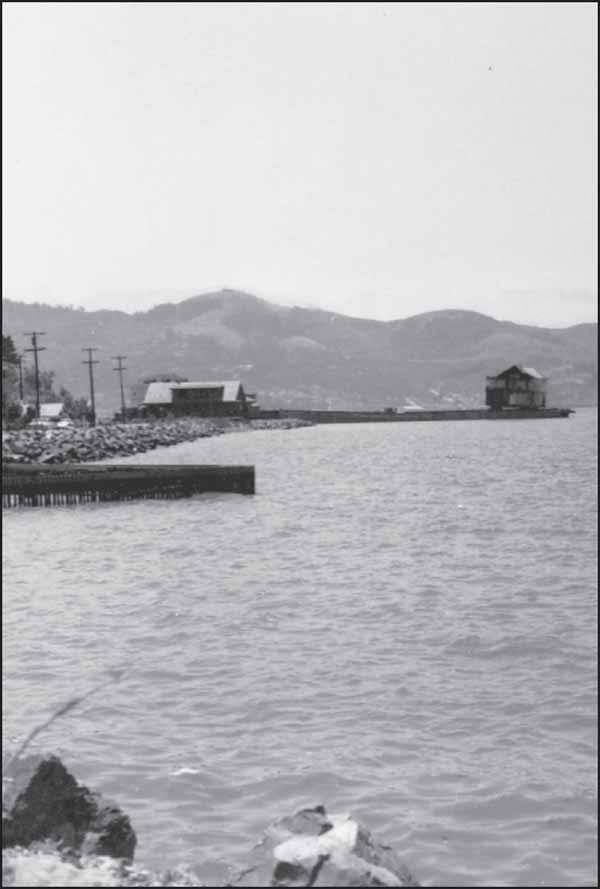

In this shot, the house and barge, with its tug captained by Master Mariner John Seaborne, is approaching the shoreline of Belvedere Island. The trip had taken one full day, battling the wind and tides in the Golden Gate all the way. The follow-up positioning and siting work was left to the Ayen house movers, and contractors were hired to restore and reconstruct the residence and landscape its grounds. (Photograph by J.R. Wilson, courtesy of the Norman Gilroy collection.)

On West Shore Road, the sections were lowered into place on newly poured concrete foundations. This view shows the house after the halves were rejoined. Amazingly, the gap between the sections was exactly the width of the first chainsaw cut made on Broadway. The original Polk drawings, found walled up in the house, guided the restoration, and damaged pilasters and moldings were replaced with plaster casts and high-quality modern-day hand carving. (Photograph by J.R. Wilson, courtesy of the Norman Gilroy collection.)

This interior shot captures just one room of the residence’s restored glory. The Moffitt Mansion move is testimony to how an idealistic gamble by a single architect inspired others to preserve important buildings for posterity. Without Norman Gilroy’s vision and determination to convince city officials that historic houses could still be moved and preserved, the later rescue and restoration of many of the Painted Lady Victorians in the Western Addition might never have happened. (Photograph by J.R. Wilson, courtesy of the Norman Gilroy collection.)

A Mediterranean-style home, built in 1926, once stood adjacent to these in the Sunnyside. Condemned by the California Highway Department to make way for Interstate 280, it was put up for auction in 1960. A young couple won the house with their $1,500 bid (about $11,650 today). They purchased an empty lot in Glen Park for $3,000, then moved the house 1.1 miles for $3,000 more. (Courtesy of the Evelyn Rose collection.)

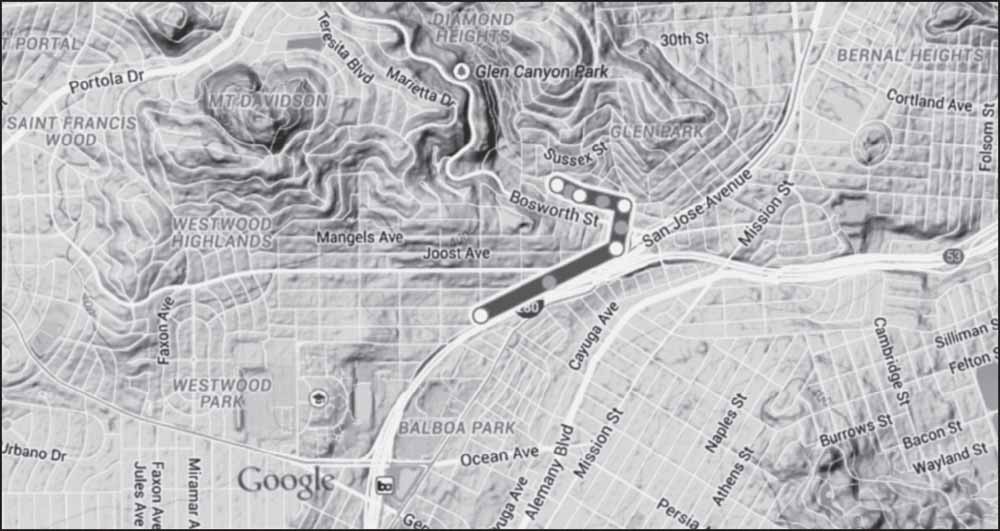

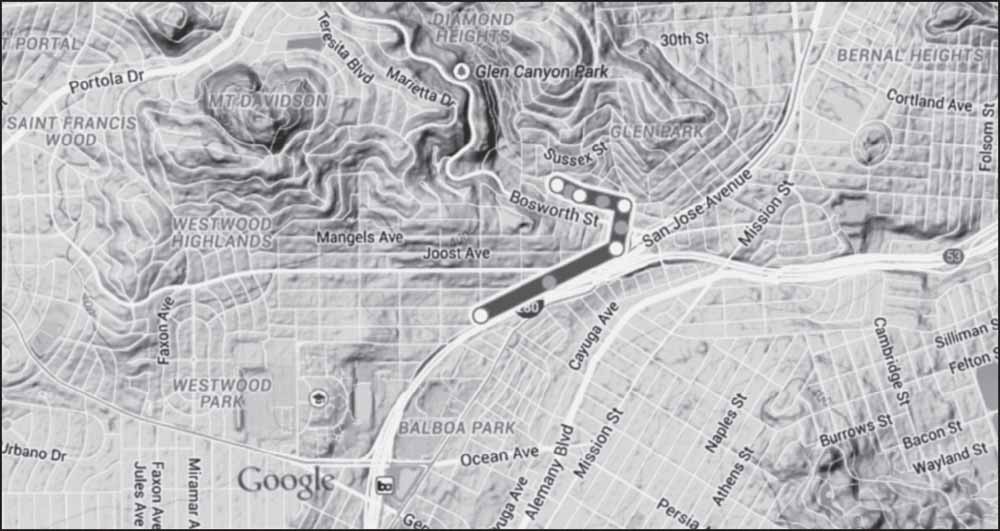

While the exact route is unclear, it likely followed Circular Avenue from the Sunnyside into Glen Park in order to avoid the steep Martha Hill. From Circular Avenue, the house may have then moved up Diamond Avenue to Chenery Street. The move took almost the whole day because of the size of the house, as well as because electrical wires had to be disconnected as they made their way along the route. (Courtesy of Evelyn Rose and Google Maps.)

At the top of the hill, the mover uncovered a manhole, inserted a large steel pole into it, attached cables to pole and house, then hoisted the house uphill at an 11 percent tilt. The front stairs broke and were later replaced for free. Because the street is narrow, the house had to be backed in with its front angled into the setback yard of a house across the street. (Courtesy of the Evelyn Rose collection.)

Pictured in 1940 is the old Engine No. 32 Fire Station in Bernal Heights (at Appleton and Elsie Streets) in the middle of the street. Jacked up on stilts, dilapidated and worn, it abuts the well-built Holly Courts, at right. On the left is a shed built for the fire hose; there was no room for it inside. The old firehouse was moved to make way for the Holly Park Housing Project. (Courtesy of the History Center, San Francisco Public Library.)

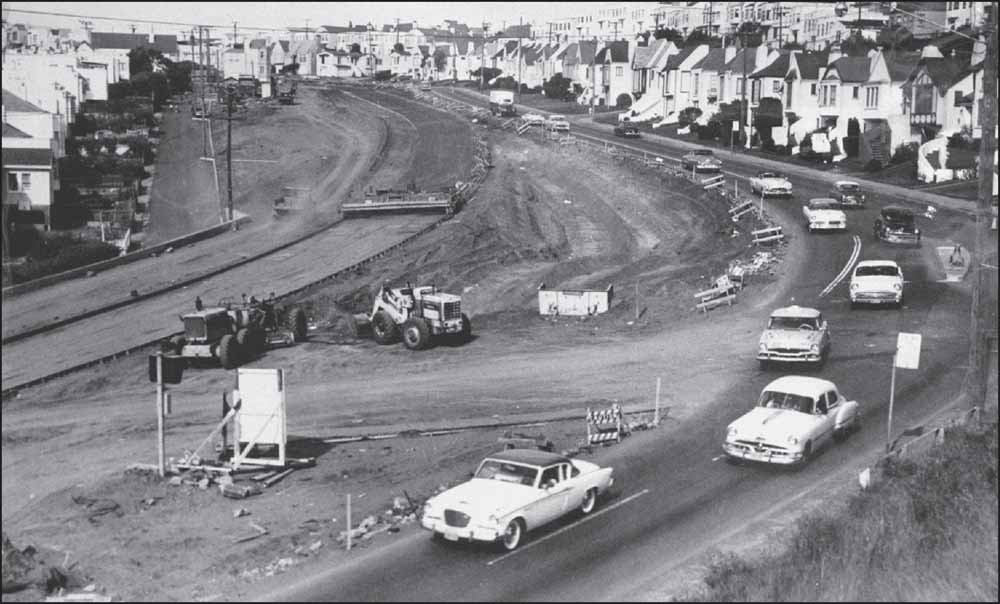

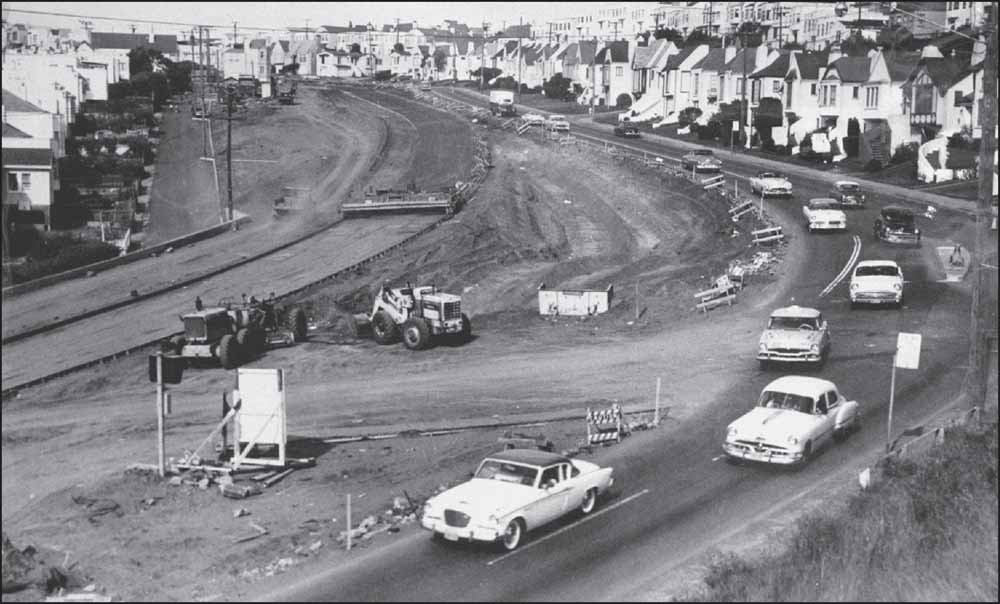

This 1958 photograph depicts the widening of Portola Drive in the last five months of the project. It was taken from Miraloma Drive. The long scar in the center of the picture once contained houses, which were moved out to permit the expansion project. The plans called for two 12-foot traffic lanes on each side of the center strip. (Photograph by Eddie Murphy, courtesy of the San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.)

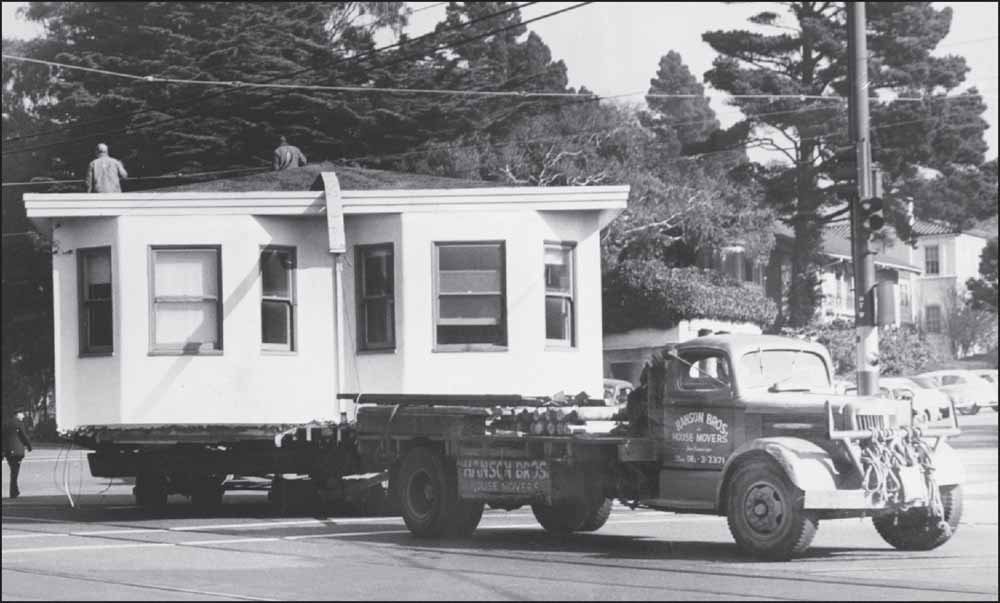

The Portola Drive construction project required the removal of houses before it could begin. A truck and trailer are shown hauling a house away from the 1200 block of Portola Drive in November 1955 to make way for the street’s widening. The house will roll past St. Francis Circle on its way to a Daly City site. This house was among first homes to be moved from Portola Drive. (Courtesy of the San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.)

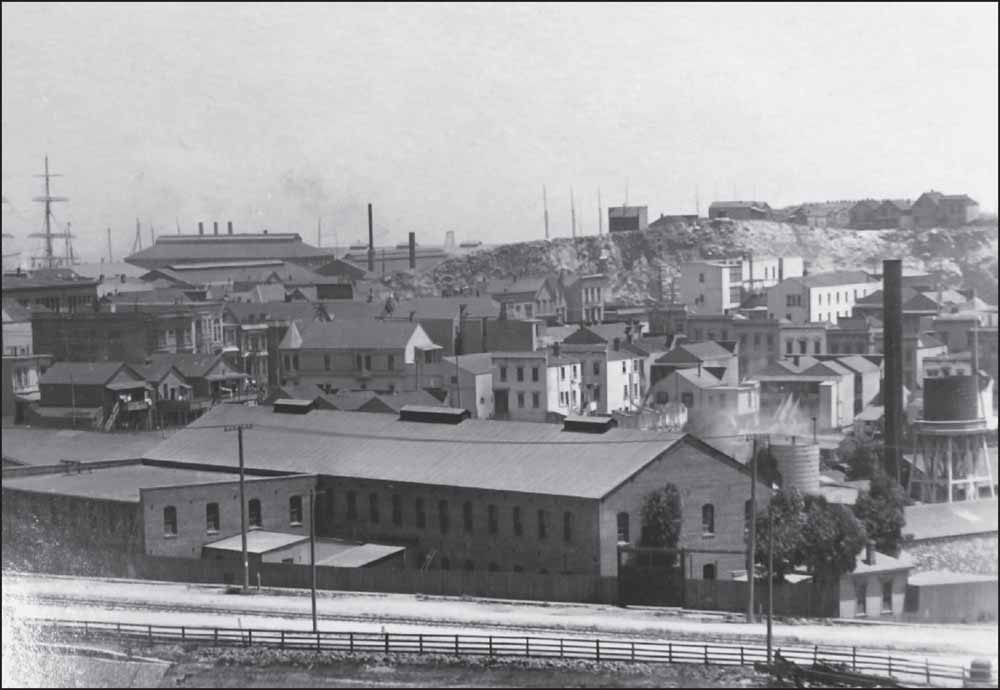

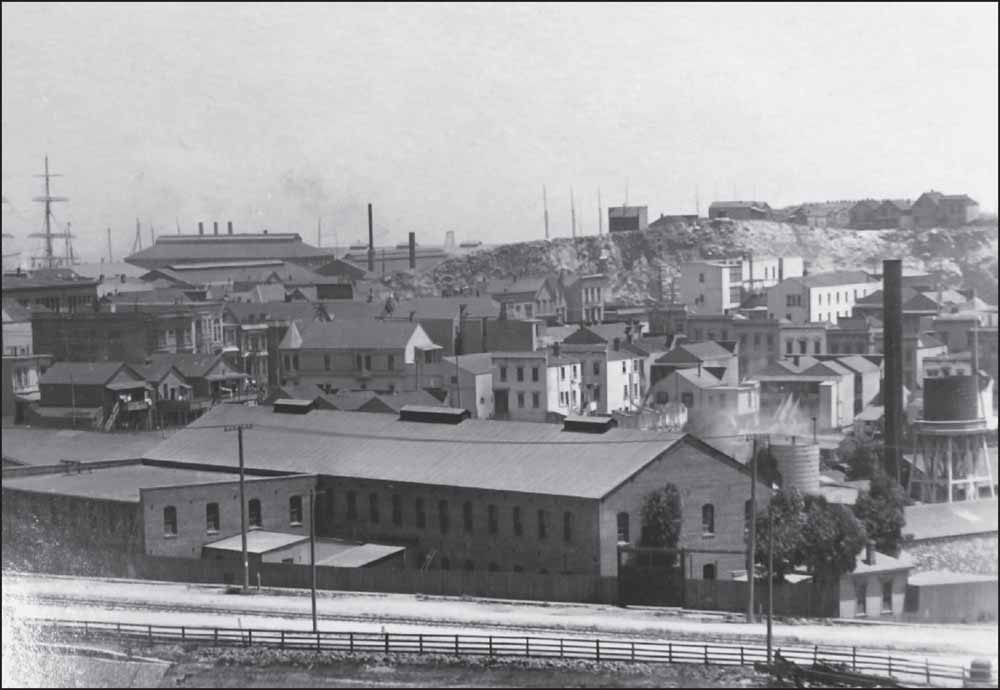

The Tubbs Cordage Company Office Building is a small frame structure now located in San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park. This 1890 structure was originally located at the Tubbs Cordage Factory at 611–613 Front Street. This image of its original (and first) location shows the Tubbs office at far right of the group of industrial buildings in the middle of the photograph. (Courtesy of the San Francisco Maritime National Historic Park and Potrero Hill Archives Project.)

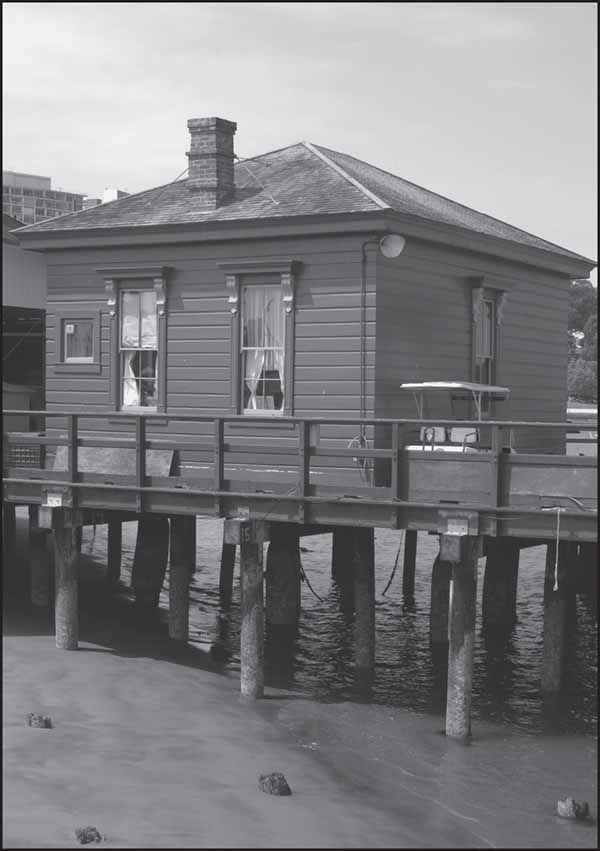

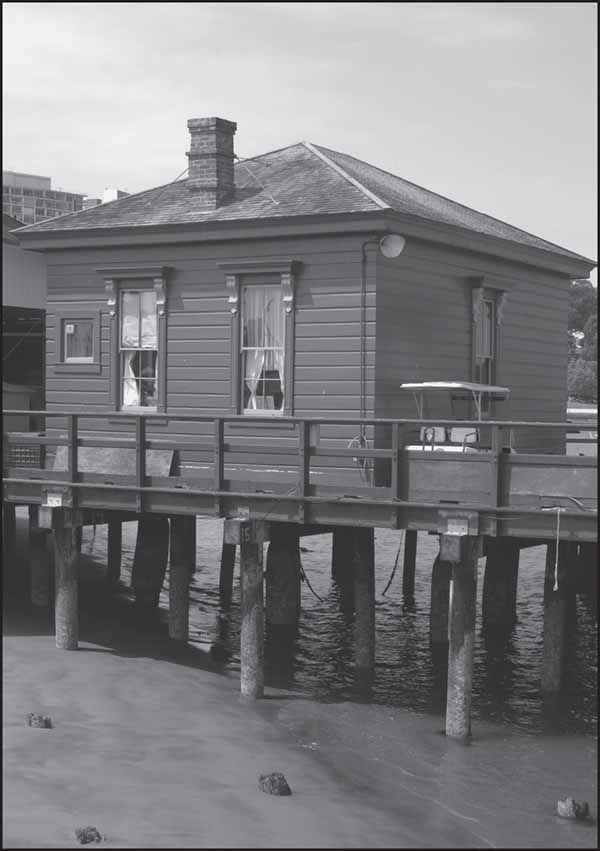

The Tubbs Cordage Company Office Building moved to the Hyde Street Pier for display and preservation in 1963 when the company closed; however, it made a second emergency move in 1990 to its current location, which rests on landfill, when the pier supporting it became unstable. This photograph is of its current location. The choice was made to move and preserve a tiny office because it represents San Francisco’s last link to an early commercial maritime endeavor—rope-making. (Courtesy of the Alvis E. Hendley collection.)

The angled building at Mission and Army Streets moved onto its lot from across the street when Army Street was widened in the early 1940s. When it was moved, it was swung around 180 degrees so that the old south portion (facing Army Street) became the new north segment. Even in the 1940s, parking was scarce. The moved building was set back on its lot, likely to create parking spaces. (Courtesy of Burrito Justice.)

Guido Giosso (right) was in the wholesale flower business when he saw a rare opportunity to buy a house for $500. When the 280 Freeway went in, numerous houses had to be moved or destroyed. He hired moving companies to do the physical moves and rebuilt the houses on new lots. His friend, contractor Joseph Caruso, entered the house-moving business on Giosso’s advice. Here, the two friends do some calculating. (Courtesy of the Giosso family collection.)

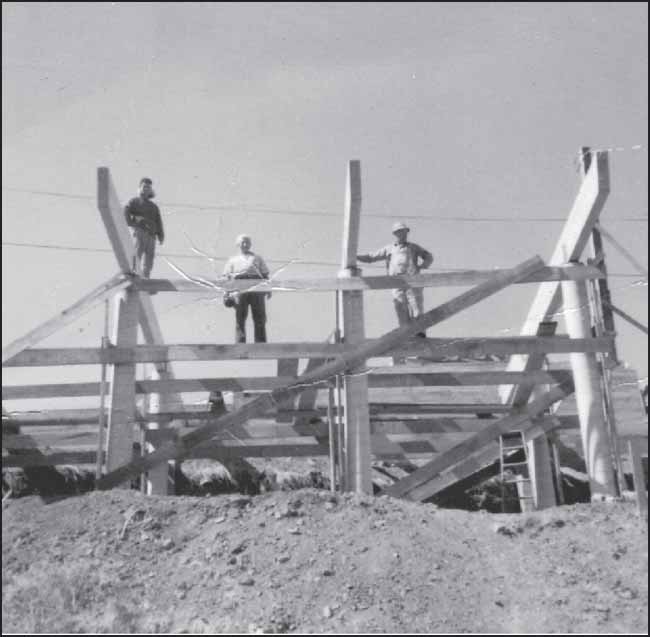

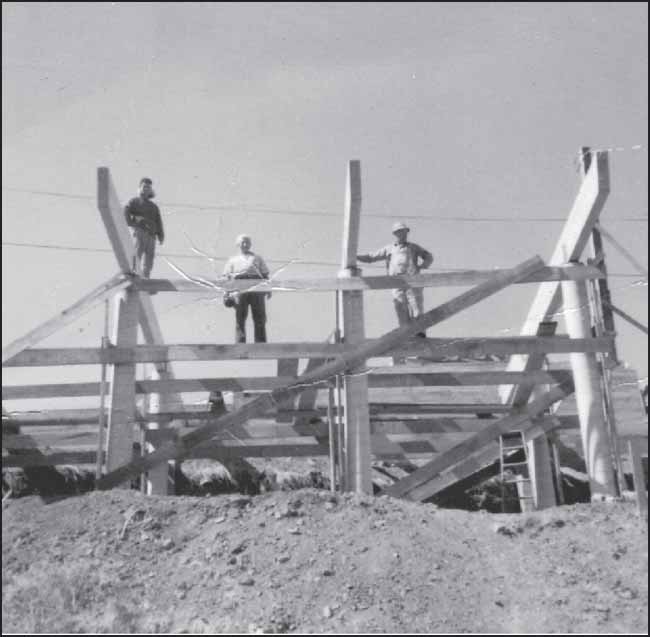

Three workers stand on framework that will eventually hold a moved house. Guido Giosso moved over 60 houses in the Oceanview, Crocker-Amazon, and Portola Districts. Nearly all were due to the 280 Freeway’s construction. At one point, he had seven to eight houses on stilts. The family knew that once the freeway was finished, the golden opportunity for making money on moving houses would vanish—and it did. (Courtesy of the Giosso family collection.)

From left to right, an unidentified worker, Guido Giosso, and Lou Jolly stand in front of a house moving to Brussels Street. A 12-foot-high wall had to be built before the house was moved into the Brussels Street lot. Four other moved houses were below it, bought over a period of two- to three-month increments. Entire blocks were often put together from auctioned, moved houses. (Courtesy of the Giosso family collection.)

While Guido Giosso’s primary business came from auctioned houses from the 280 Freeway project, he also moved other buildings. This two-unit flat was originally on Twenty-Second Avenue and Cabrillo Street. It had to be moved to make way for a new school. It is now on Forty-Eighth Avenue but is still a two-unit flat. It moved in 1968. (Courtesy of the Giosso family collection.)

A home moved in 1968 is being backed into its new lot on Bayshore Boulevard, next door to the Planter’s Peanuts building. Auctioned houses varied in price; some sold for more money, and some sold for less. Part of the equation was the size and shape of the building. A bidder had to have the right-sized lot to take the building. Therefore, sometimes larger buildings sold for less than standard-sized houses. (Courtesy of the Giosso family collection.)

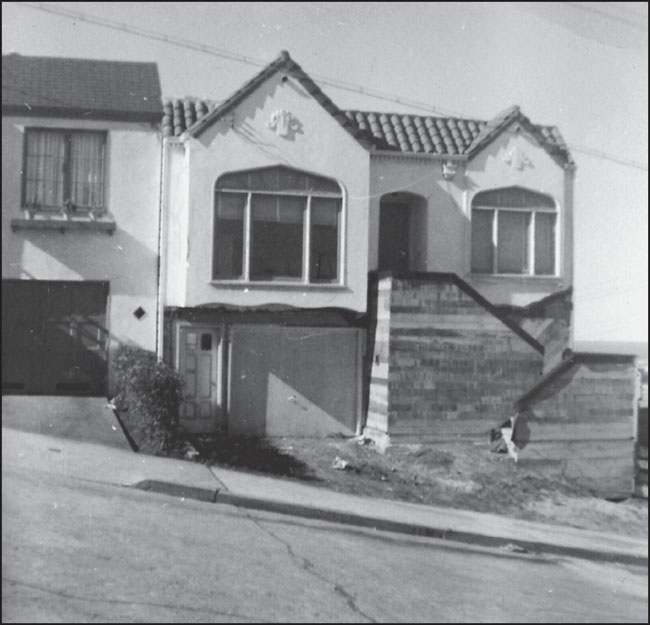

This house had to be turned and raised up 10 feet before it was properly situated on its lot. It was moved from the nearby city of Colma to a vacant lot near the Bayside Motel in the neighborhood known as Little Hollywood. Some of the houses that had to make way for the 280 Freeway were beautiful homes that were only 10 to 15 years old. (Courtesy of the Giosso family collection.)

This looks like a typical San Francisco hill of row houses, but they were not originally built that way. Five of the houses in this photograph were moved onto their lots and were purchased at auction over a period of months. The 280 Freeway created new neighborhoods, even as it destroyed others, thanks to the efforts of entrepreneurs who saw opportunities in bargain houses. (Courtesy of the Giosso family collection.)

A moved house is raised on cribbing, on its new lot and in position. The house is placed six inches higher on cribbing, which allows the bottom to be built underneath before it is dropped into place as the top floor of the structure. A retaining wall had to be built around this Brussels Street house. (Courtesy of the Giosso family collection.)

Guido Giosso and his family and workers stripped this house and tore the bottom off in preparation for moving. Once it was moved, it was left raised as they rebuilt its foundation. In this photograph, the differences between old top and new bottom can clearly be seen. When stucco is applied, the house will look as though it were built as one unit. (Courtesy of the Giosso family collection.)

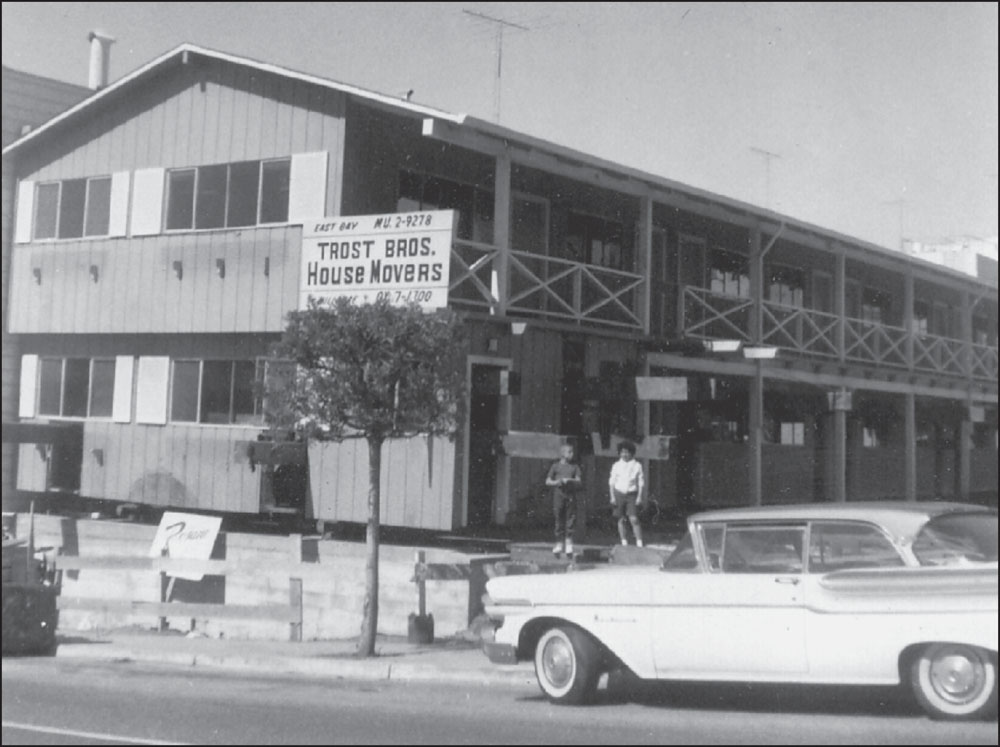

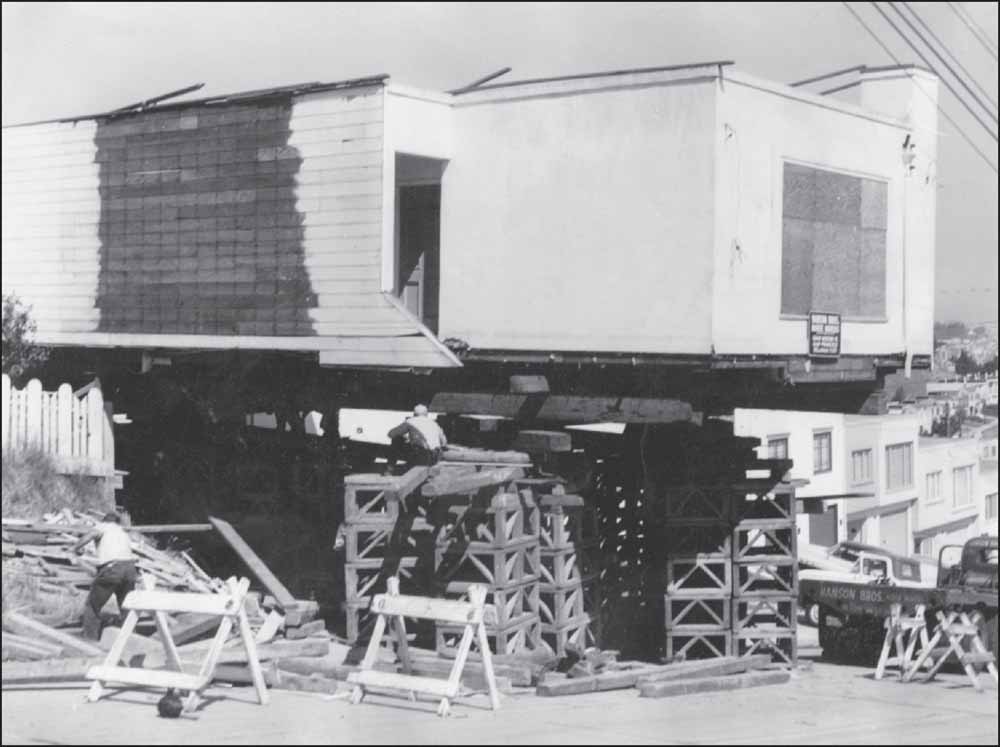

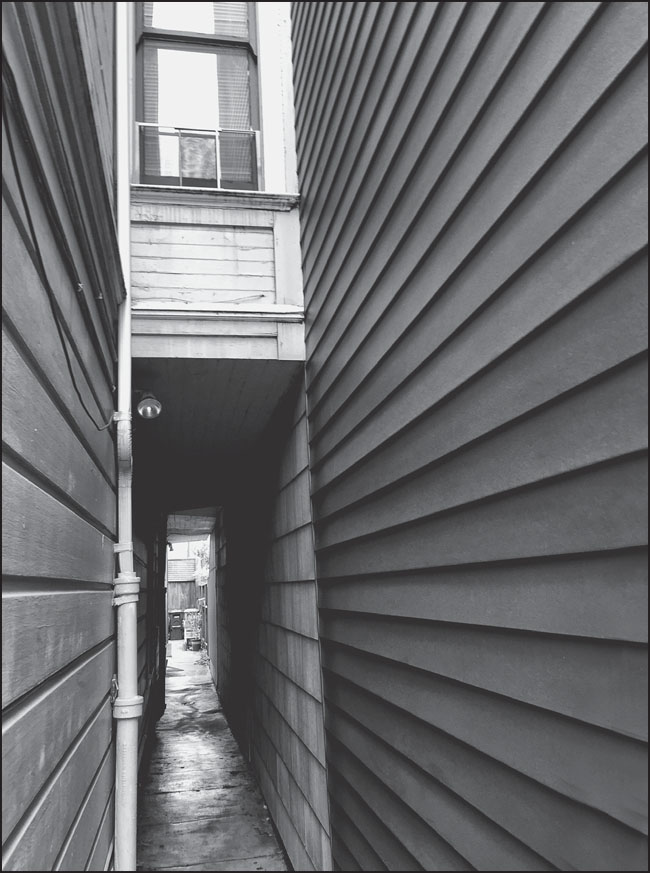

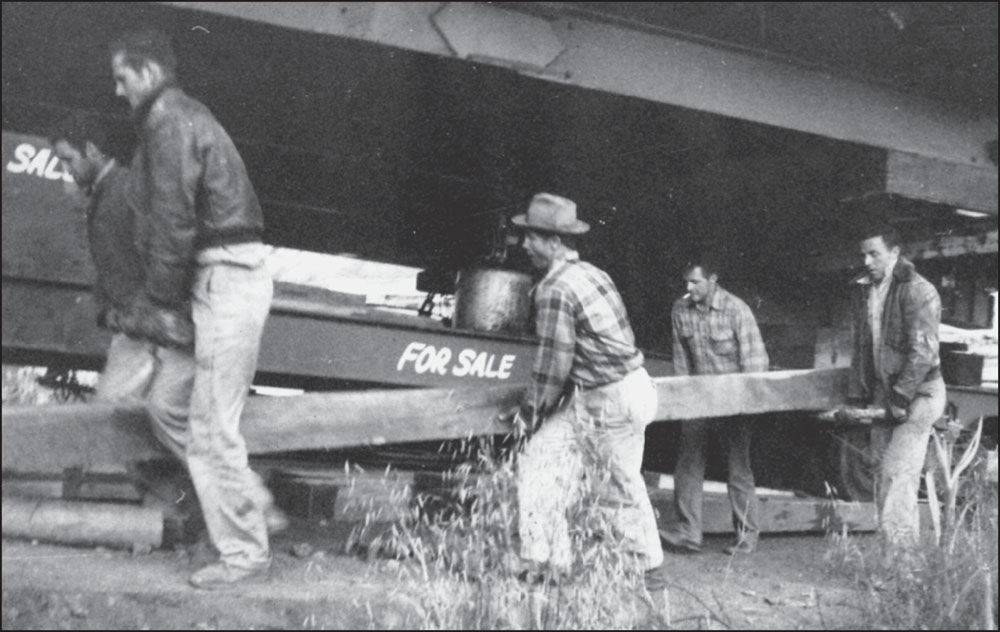

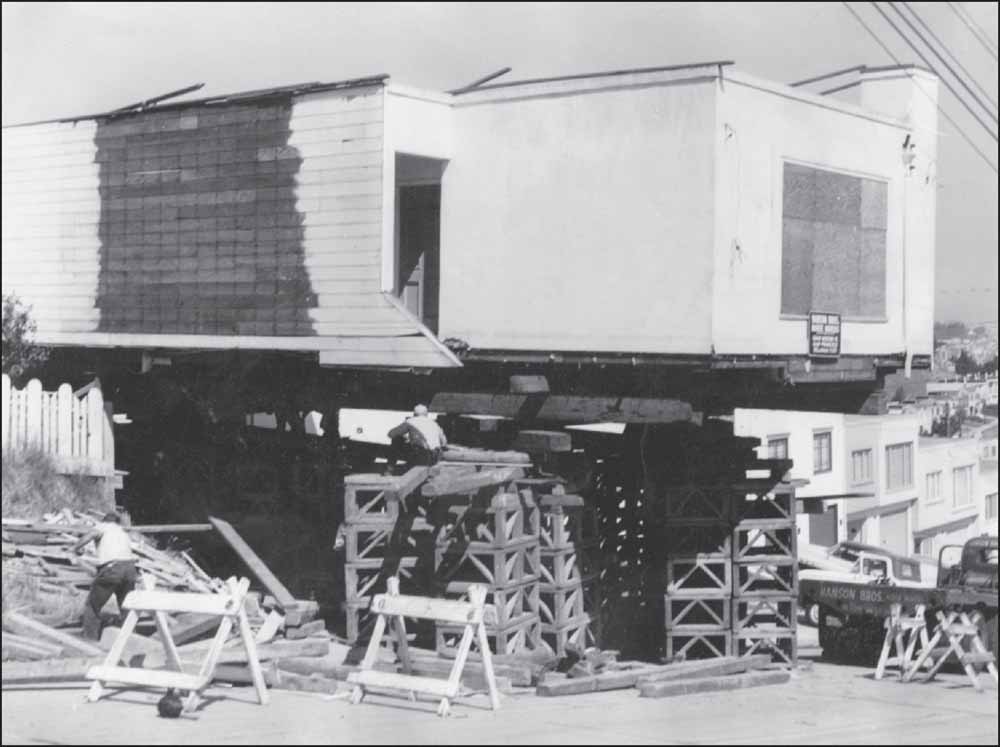

Building out the bottom of the house involves leaving enough extra clearance to allow it to be lowered into place when ready. The Hanson Brothers Moving sign is displayed in the window, indicating that this building was moved by the company. Workers under the house are building the new garage. (Courtesy of the Giosso family collection.)

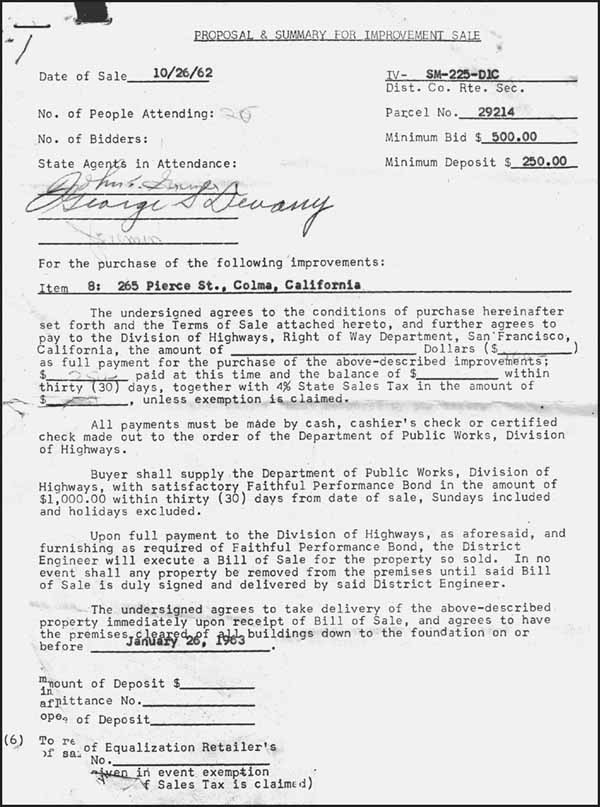

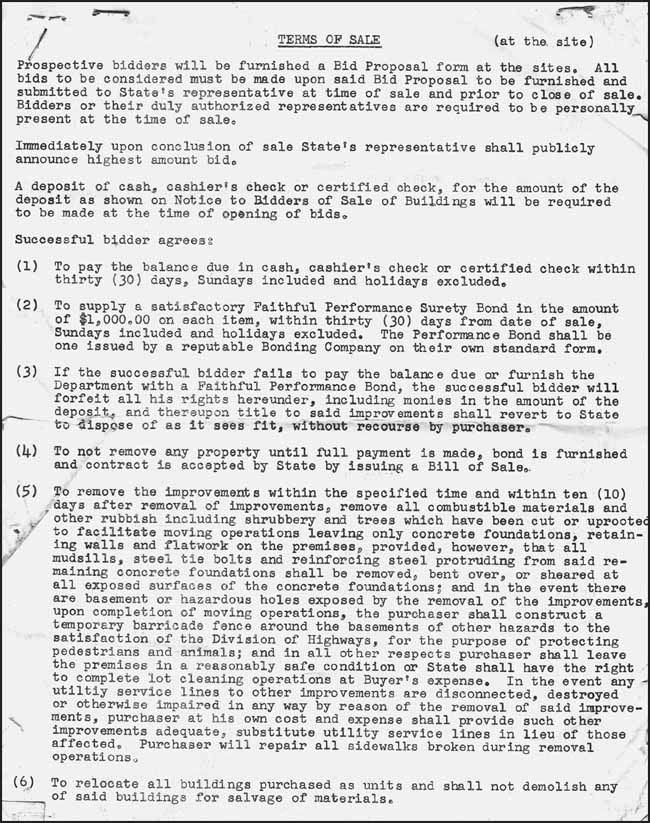

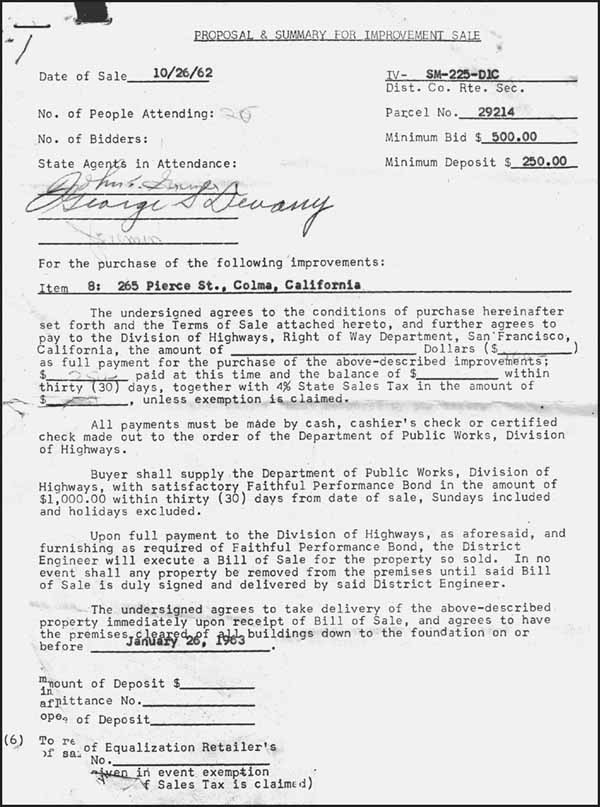

The terms of sale for winning a Division of Highways auction bid for a building were very specific. This three-page contract documents what can and cannot be done with such a structure. When the Giosso family members won this Colma building, they had to pay cash and supply a $1,000 performance bond before a bill of sale could be issued. (Courtesy of the Giosso family collection.)

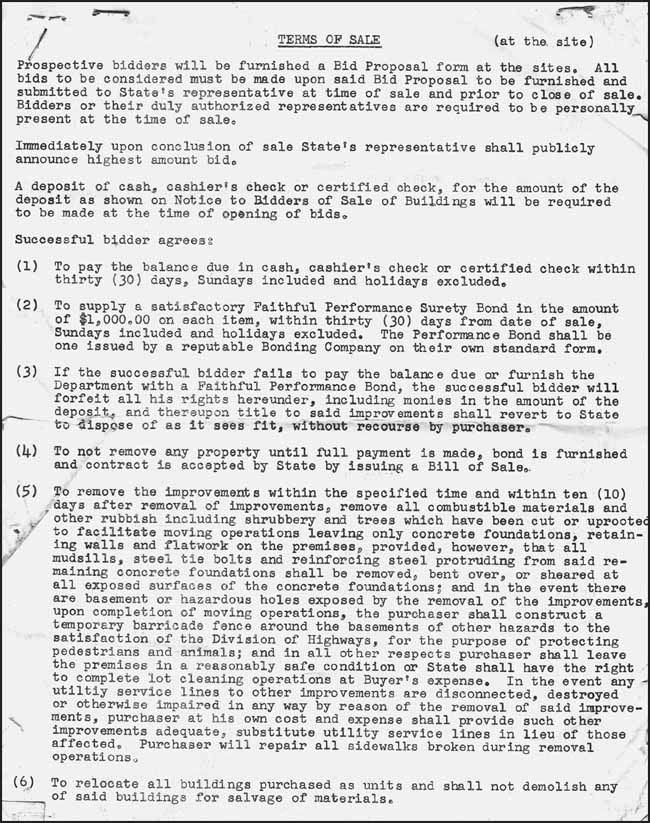

Page two of the contract outlines further terms of sale, which include forfeiting all rights if payments were not made in 30 days and agreeing to relocate the buildings as units. It was not permissible to demolish the building for salvage of materials under the auction terms, and buyers had to repair sidewalks or any utility lines broken during the move. (Courtesy of the Giosso family collection.)

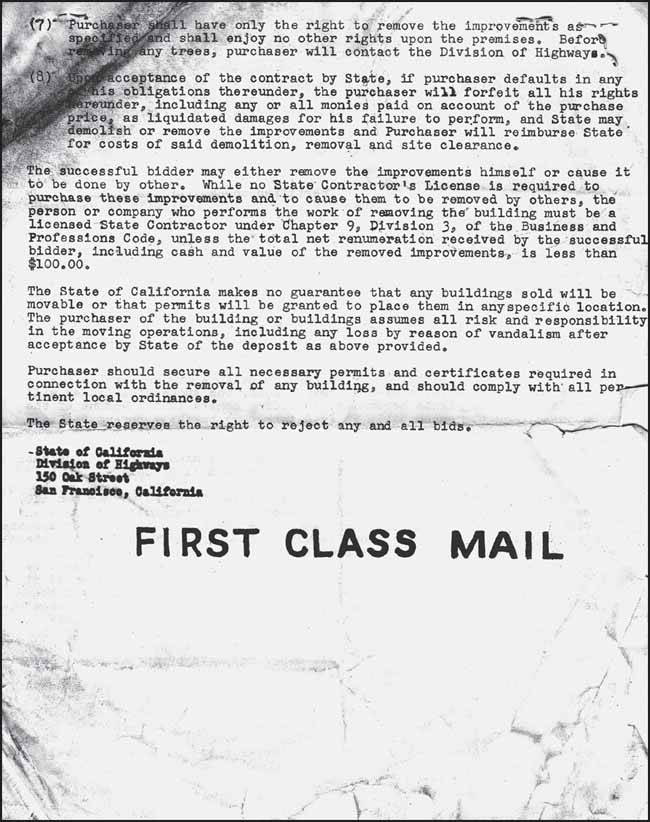

Purchasers could not move trees on the lot without contacting the Division of Highways for permission. No state contractor’s license was required of the buyer to purchase or move the buildings, but the actual move had to be made by a licensed state contractor. The division made no guarantees that the structures were actually moveable or that permits would be issued for specific destinations. (Courtesy of the Giosso family collection.)