Six

REDEVELOPMENT

RELOCATING THE WESTERN ADDITION

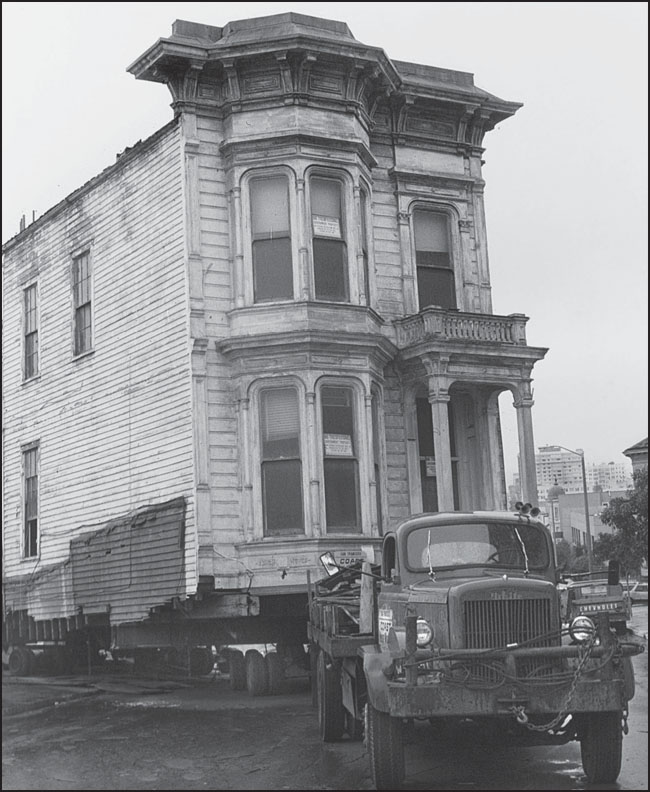

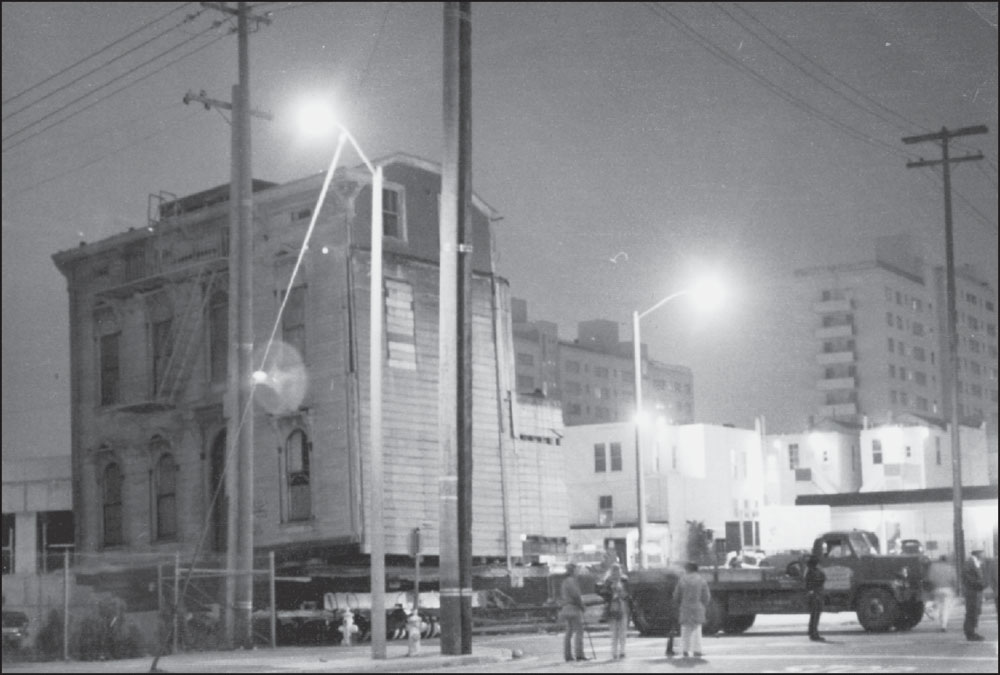

The story of the Western Addition Victorian house moves is one replete with social and political struggle. The Western Addition had long been viewed as a dangerous slum, but by declaring the neighborhood “blighted,” the city became eligible for federal funds to tear down the old Victorians and replace them with new structures. Members of the community tried to save their neighborhood, but by the end of the 1970s, approximately 2,500 Victorians had been torn down, 883 businesses had closed, and 20,000 to 30,000 residents had been displaced. In all, 12 homes were relocated in what may have been the largest house moving project in San Francisco history. In this photograph, trucks laboriously pull the structure up the street to its new location, which could be many blocks away. Most traveled about one mile to their new resting place. Weight blocks had to be put on this particular building to keep it from rolling down the hill. Now at Ellis and Divisadero Streets, it was formerly located at 3875–3879 Sacramento Street. (Courtesy of the David Glass collection.)

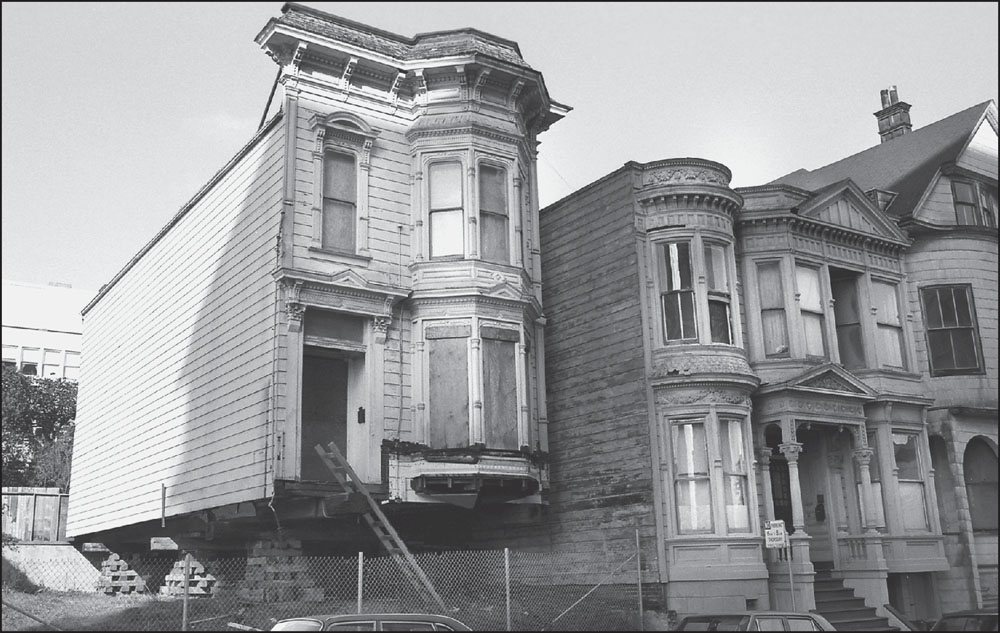

This Buchanan Street Victorian, moved in 1977, was parked at the curb for several days, awaiting moving trucks. The houses were moved in groups, at night, but they had to be “staged” to move in these groups, which sometimes meant that the houses rested in the street until it was their turn. (Courtesy of the David Glass collection.)

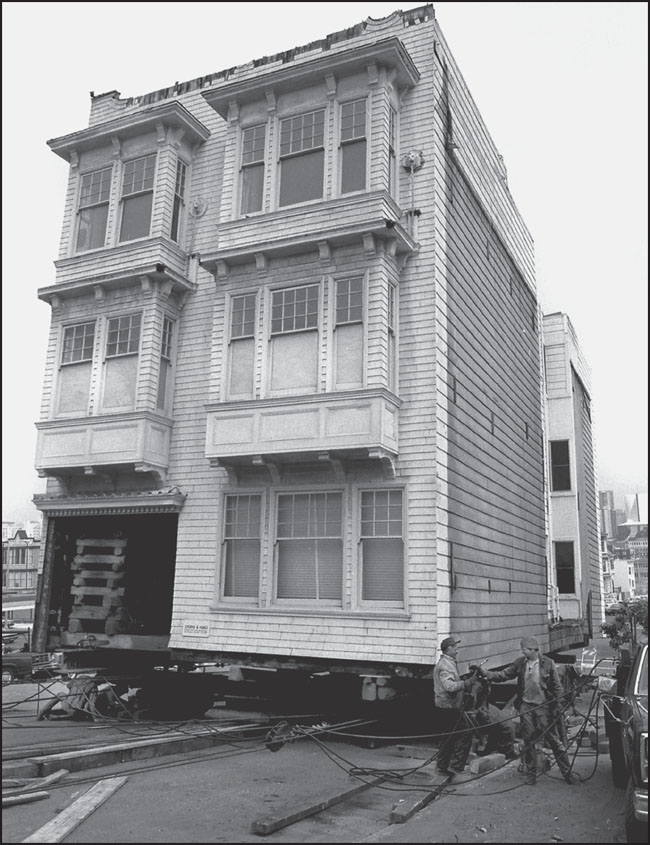

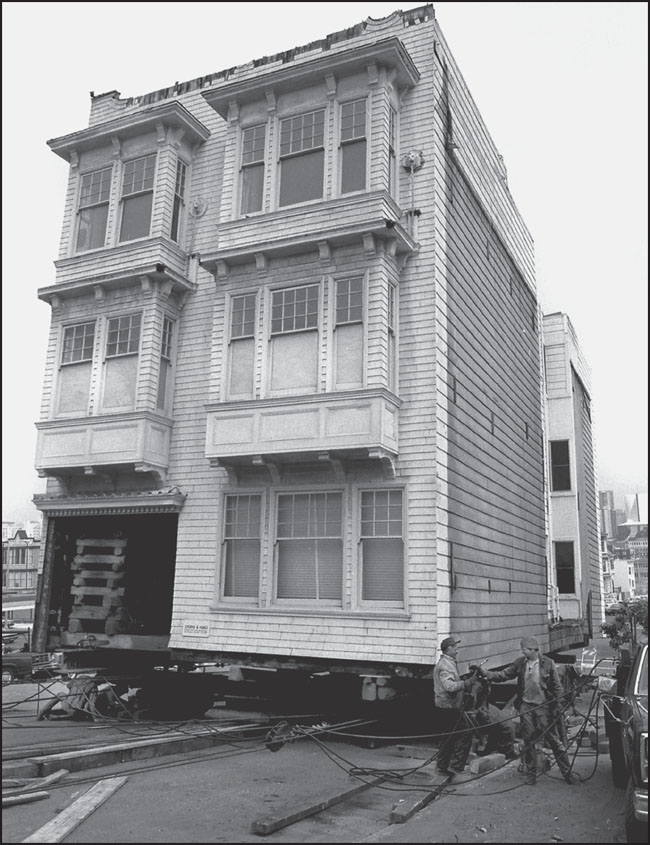

Buildings can be moved in one of three ways, intact, partially disassembled, or completely disassembled. Relocating a building as one unit costs less and preserves the building’s original integrity. Box cribbing, seen here under this Ellis Street house, supports the structure as the building is lifted in increments. A flatbed truck or hydraulic dollies can then move the building. After the move, the structure is lowered, reversing these steps. (Courtesy of the David Glass collection.)

This close-up view of the Divisadero and Ellis Streets house displays the importance of cribbing in the moving operation. The house mover expressions “lift an inch, crib an inch” and “pack as you jack” are common reminders to operators of the importance of cribbing in securing and protecting a building before and after its move. (Courtesy of the David Glass collection.)

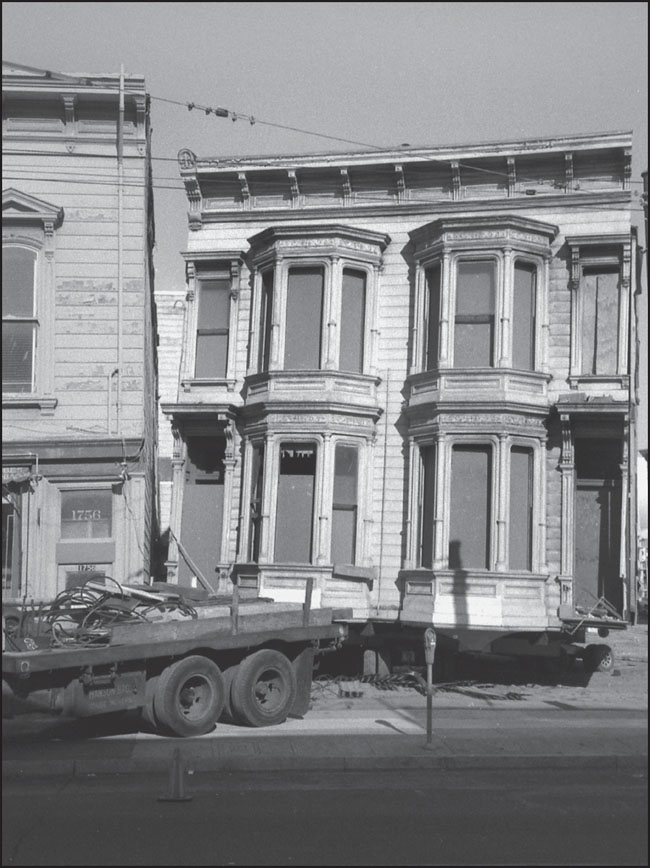

One of the challenges involved in moving a building in a high-density city such as San Francisco is to angle it out of position in its old location and slip it into its new location. This photograph illustrates some of the problems. Note the parking meter in front and the building right next door. This photograph was shot on the 1700 block of Fillmore Street. (Courtesy of the David Glass collection.)

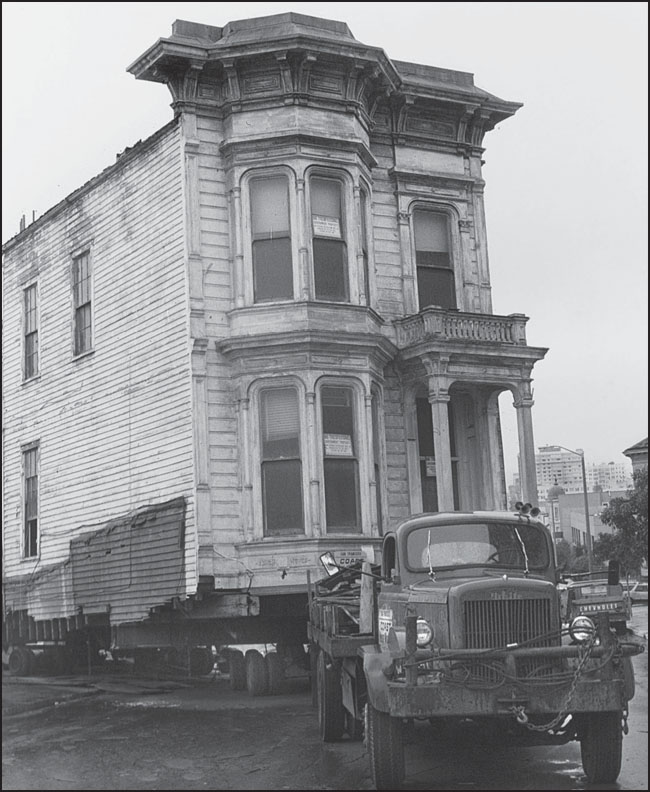

How can a truck transport a house weighing tons? Here, a Victorian building is raised and placed on rollers so that a truck can tow it up the street. In the early days, the horse/capstan method was used to move buildings. Mechanical steam donkeys evolved into flatbed trucks as the preferred moving machine of choice. (Courtesy of the David Glass collection.)

Jacks, trailers, and human attention were all required to move these large historic structures. Here, a laborer monitors the placement of support and transport equipment on a Western Addition house. This remains the largest mass-building-moving project in San Francisco’s history, even though the number of houses saved from destruction was miniscule in comparison to those that were torn down. (Courtesy of the David Glass collection.)

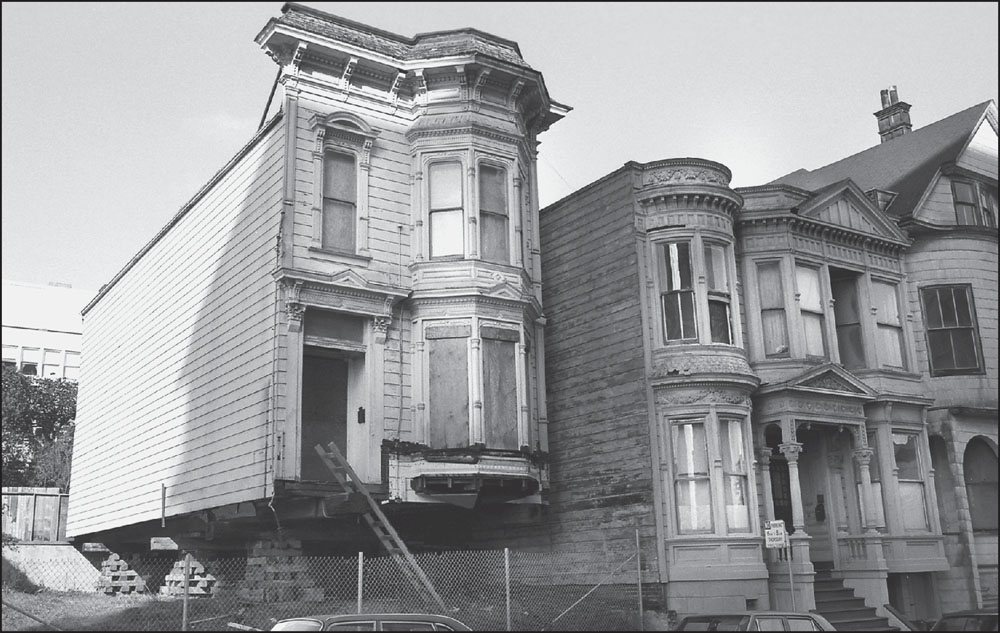

All windows on this Post Street house have been boarded up in preparation for its relocation. Other photographs show some homes being moved without boarding up doors and windows. Some of the Victorians had to be shoehorned into place, as in a Turk Street move where the dimensions were miscalculated. The three inches of siding had to be shaved off by a carpenter knowledgeable about Victorian homes, while standing on a 40-foot ladder. (Courtesy of the David Glass collection.)

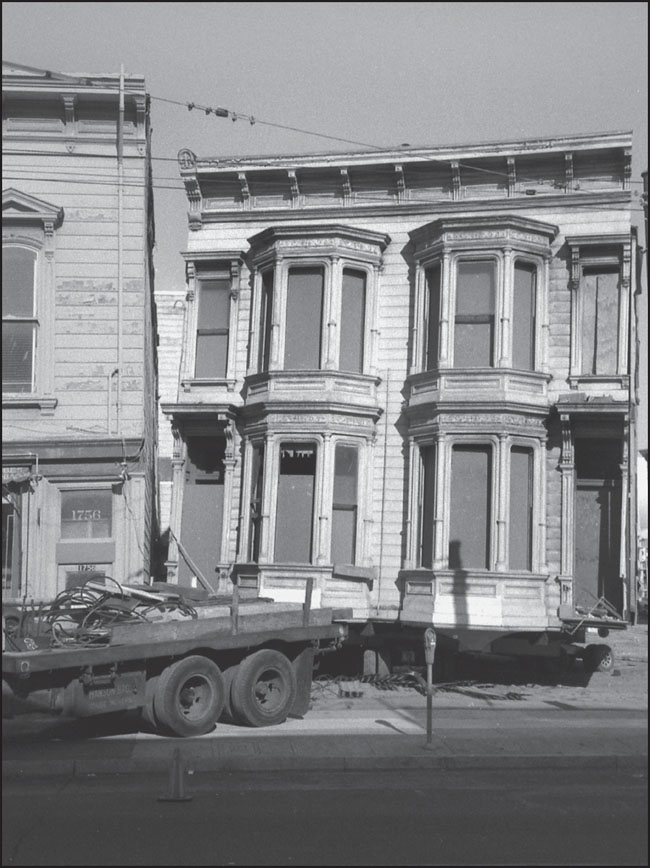

Fillmore and Sutter Streets saw much activity in 1976 as the demolition deadline grew near. Here, three Victorians are prepared to move (nearly simultaneously) to their new locations. There was a method to the moving madness—houses had to be moved in the proper order because there was no passing room. The buildings now sit on the 1700 block of Fillmore Street, part of a neat row of restored Victorians. (Courtesy of the David Glass collection.)

While most building moves are carefully orchestrated, only a few cities in the country have had massive simultaneous structural moves. This group of houses was moved from Japantown a few blocks away. Before it became Marcus Books on Fillmore and Post Streets, one building from this group once housed the infamous jazz joint Jimbo’s Bop City. (Courtesy of the David Glass collection.)

This side view of a building moved from Fillmore and Sutter Streets in 1976 shows just how long these Victorian structures were. The other structures on the same block are all ready to go, too. A dozen century-old buildings had to be moved across freeway on-ramps at night to minimize any traffic impact. (Courtesy of the David Glass collection.)

This 1976 photograph shows the Fillmore and Sutter Streets building hooked up and ready for its journey. The effort involved not only structural engineers, but also required utility crews to accompany the moving houses to remove and then re-string power lines, streetlights, and trolley lines. An escort cavalcade of 30 motorcycle police cleared the streets once the houses were underway. (Courtesy of the David Glass collection.)

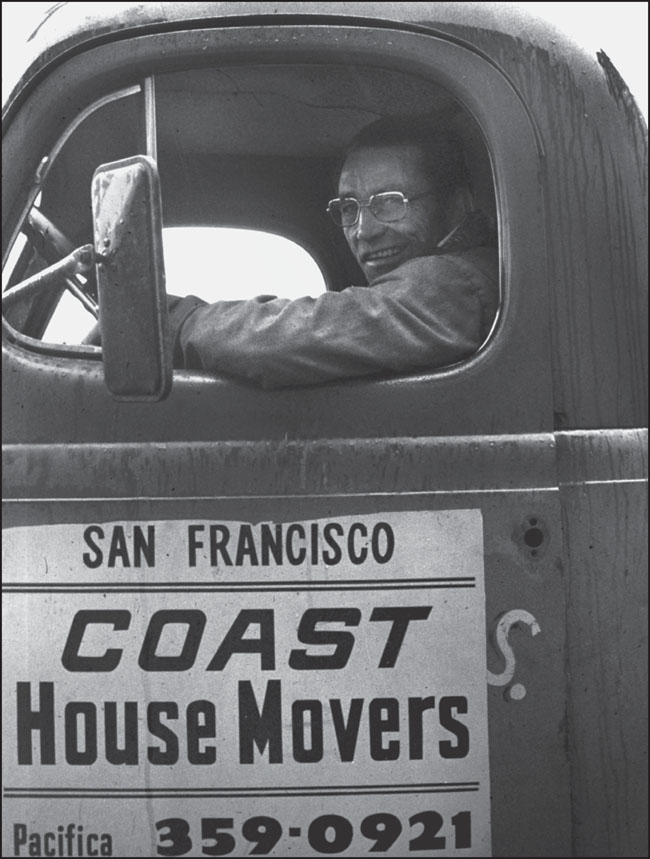

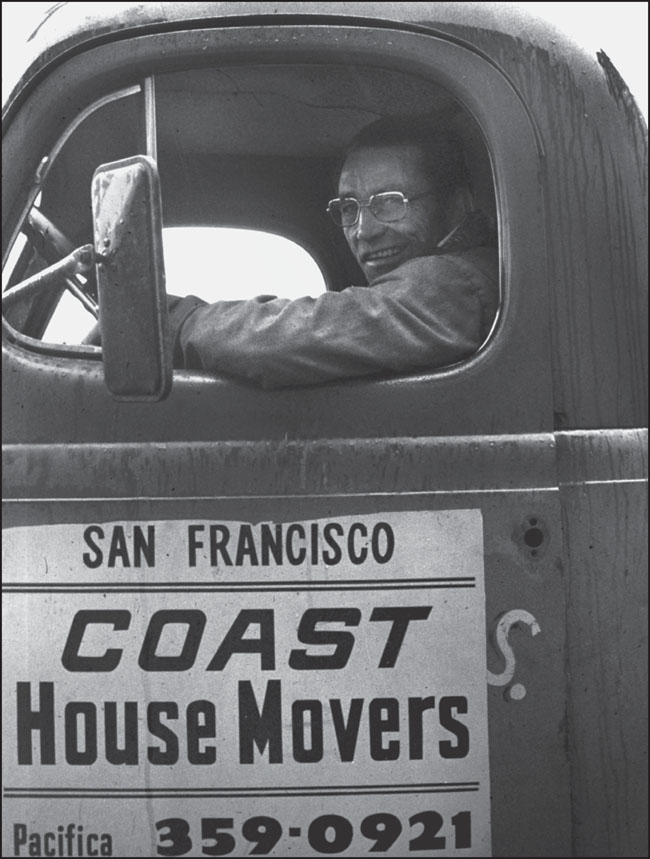

Coast House Movers (located just south of San Francisco) was just one of a number of house-moving professionals involved with the project. Here is an old Coast House Movers truck driven by mover Manuel Pereira, waiting his turn. This man broke his back in 1973 and was never supposed to walk again, but here he is, moving buildings. (Courtesy of the David Glass collection.)

Workers prepare a shored-up Ellis Street house for the arduous physical move to its new home. Note the cribbing in place. Hydraulic lifts raise the house slightly, and three dollies are used (two at the rear and one in the front) to ultimately roll the house along the street, towed via truck. (Courtesy of the David Glass collection.)

Here, workers attempt to back a three-story Victorian apartment building up a fairly steep hill. Planks are placed in front of the various wheels. If a set of wheels drops during a move, the entire house could topple over. The planks help prevent this. (Courtesy of the David Glass collection.)

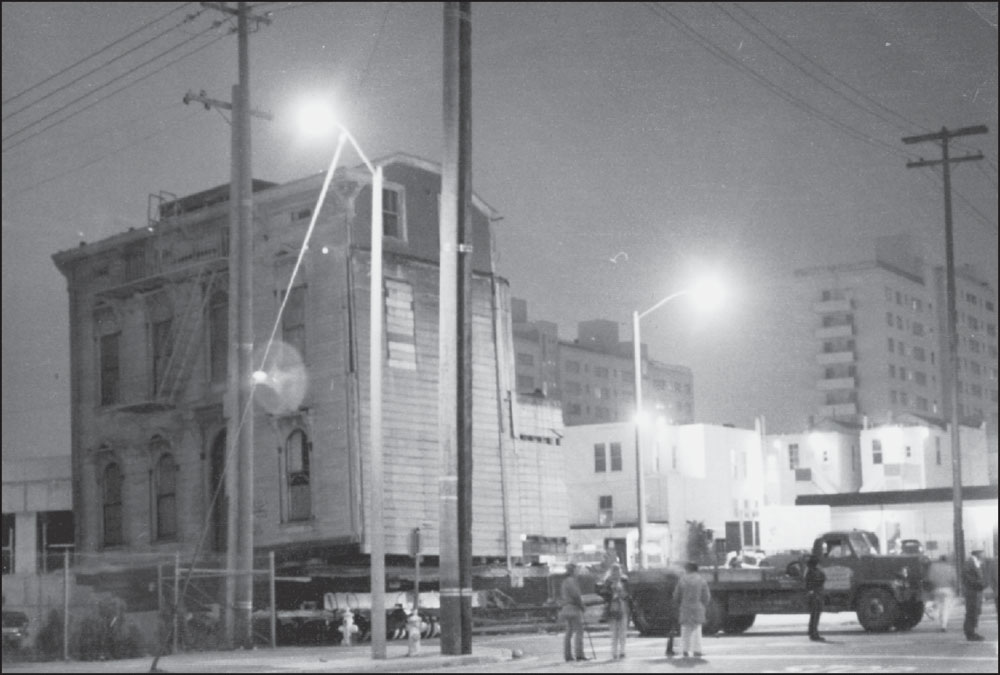

Hubert Trost, a longtime Bay Area mover, had quit the local business and was in Alaska moving buildings when he got the call to consult on the Western Addition moves. This photograph was shot at night; the trolleys closed at 2:00 a.m., and the movers had two to four houses ready to go in a convoy. The other house movers would pull them to their lots, and Trost’s team would place them. (Courtesy of the Hubert Trost collection.)

Trost is hauling a building at Golden Gate Avenue near Broderick Street. Hubert Trost helped Coast House Movers with this historic endeavor. It is no mean feat moving a 110-ton house up or down a hill. Two trucks were often stationed uphill during the move, with steel cables embracing the house. If it got out of control, the trucks theoretically could hold it back. (Courtesy of the Dennis O’Rorke collection.)

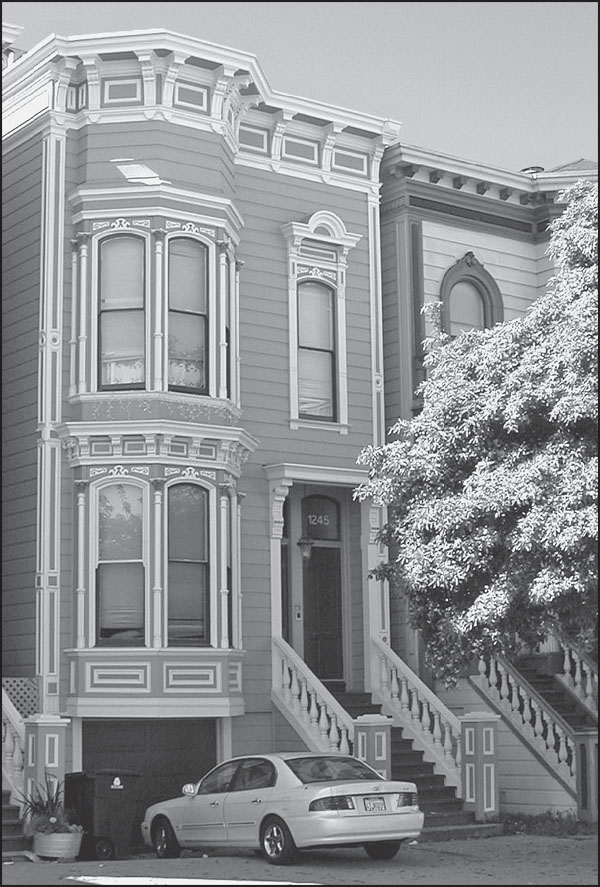

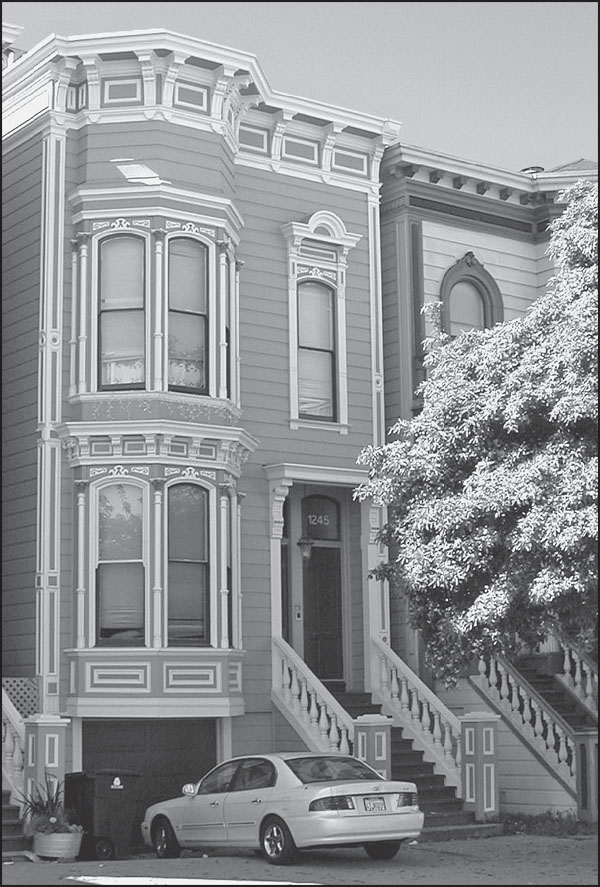

This Scott Street building was one of eight buildings moved onto a two-block development within the Western Addition Area No. 2 and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. A house like this could be purchased from the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency for $1 plus relocation and restoration costs. (Courtesy of the Alvis E. Hendley collection.)

Ayen House Movers of San Leandro was one of several companies involved in the Western Addition moves. They led the parade of Victorians across town and used a flatbed truck to pull the first 100-ton Victorian home. The company is no longer in business today, but its legacy lives on in the houses that were moved in the 1970s. This three-story building is moving at Ellis and Divisadero Streets. (Courtesy of the David Glass collection.)

A line-up of buildings waiting to be moved on Fillmore Street gives evidence of the coordination required for such a massive building-moving endeavor. Unlike a single building’s move, the evacuation of several structures at once required precise measurements, a coordinated effort between all city agencies, and the cooperation of several building-moving experts who had won bids to move the houses at an average of $12,000 per house. (Courtesy of the David Glass collection.)

One moved building rests at Divisadero and Ellis Streets. In 1971, San Francisco Heritage was formed to identify 12 Victorian houses that were scheduled for demolition but could be saved. The Redevelopment Agency agreed to sell the houses only if they were moved to a new location. At a public auction in the summer of 1972, San Francisco Heritage entered minimum purchase bids, gained ownership of the houses, and identified new homeowners to rehabilitate them. (Courtesy of the David Glass collection.)

Some 2,500 Victorian homes were demolished in the name of urban renewal when the city’s redevelopment agency razed the predominately black Fillmore area in the 1970s in a move that destroyed San Francisco’s largest African American community. Over 800 businesses were closed, and well over 4,000 households were displaced. This photograph captures Coast House Movers as they tow a building down the street between Divisadero and Ellis Streets. (Courtesy of the David Glass collection.)

Before a building can be moved, it has to be jacked up. Here, a Trost mover prepares a huge Victorian building. Once the building is cut loose from water, sewage, and utilities, holes are drilled through the foundation, steel beams are slid underneath, and hydraulic jacks lift it up. If it is not high enough, it is jacked up and supported on cribbing, and then the jacks are repositioned on cribbing to raise it further. (Courtesy of the David Glass collection.)