Born: Lydia Foucar, February 18, 1895, Friedrichsdorf, Germany

Died: 1980, Friedrichsdorf, Germany

Matriculated: 1920

Locations: Germany

Surviving with gingerbread cookies (Formgebäck): an odd proposal, but precisely how Lydia Driesch-Foucar supported her young family through difficult times. Furthermore, her unusual life and work crafting cookies have come to be exemplary of many aspects of the history of design during the Nazi era. Known only to experts as a Bauhaus member, she arrived at the Weimar Bauhaus a fully trained ceramist. She received her degree from the Munich School of Applied Arts (Kunstgewerbeschule) in 1919 and, until 1921, designed models for the Hutschenreuther porcelain factory in Selb. While still in Munich, she met the art student Johannes Driesch, whose glowing letters soon convinced Foucar to follow him to Weimar. In May 1920, both signed up to work in the Bauhaus pottery workshop in Dornburg under the direction of sculptor Gerhard Marcks, who, as his teacher, friend, and patron, treated Driesch like a son. The young couple was married on Pentecost 1921 and welcomed their first son, Michael, that September; from then on, Driesch-Foucar’s sole workshop activity was cooking for its eight to ten members. The couple’s approximately forty surviving works from this time show just how strongly their work was influenced by the Bauhaus, a change that led Hutschenreuther to end their collaboration with Driesch-Foucar. It was around this time that Driesch turned away from the modern Bauhaus ideas and left the pottery workshop to become “the best painter in Germany.” Over the next nine years, the couple raised four children and often lived apart. While Driesch-Foucar spent most of her time at her parents’ house in Friedrichsdorf, her husband lived and worked primarily in Weimar, Erfurt, Dresden, and Frankfurt. The couple’s correspondence clearly conveys the bitter poverty that defined their daily lives.

After her husband’s untimely death in February 1930, Driesch-Foucar was practically destitute. The hand-sewn leather animals she sold to supplement the household income could not be mass produced, and she was unable to find a publisher for the children’s books she created; all that was manufactured was an (ultimately unsuccessful) game called “Schnipp-Schnapp-Spiel.” Finally, in November 1932, Wilhelm Wagenfeld—like Driesch-Foucar a former Bauhäusler, and, since spring 1931, a member of the artistic staff at the Schott Glassworks in Jena—commissioned the young widow to design a brochure for milk bottles and wrapping paper. The request was for verses in the old-fashioned Sütterlin script, anything but a modern design. As instructed, Driesch-Foucar delivered it in the form of a postcard-sized, accordion-fold pamphlet, which was printed and paid for by the company. Two of her wrapping paper designs from 1933 were shown to the glassworks’ new artistic consultant, László Moholy-Nagy. Her kindergartenesque style was hardly compatible with his advertising strategies, so these designs were paid for but never made. “Nothing worked,” expressed Driesch-Foucar a short time later, taking stock of her unsuccessful efforts to make a living as an artist.

Driesch-Foucar’s next attempt was making Lebkuchen, a type of gingerbread cookie also referred to in German as Honigkuchen (honey cake), Pfefferkuchen (pepper cake), or Formgebäck or Formkuchen (cutout cookies or cake). As she later described the family history behind this business idea: “It was also the first time I tried my hand at baking Lebkuchen, therefore I cut all kinds of different figures out of the brown dough and baked them. It was the beginning, so to speak, of what later became my Lebkuchen workshop and a tradition that lived on between the Marcks family and us for years: exchanging Kuchen with accompanying sayings at Christmastime. The Marckses’ particular specialty was a white anise Kuchen, which he would cut out, and we had our Lebkuchen figures … decorated with white icing and colored sugar pearls.”

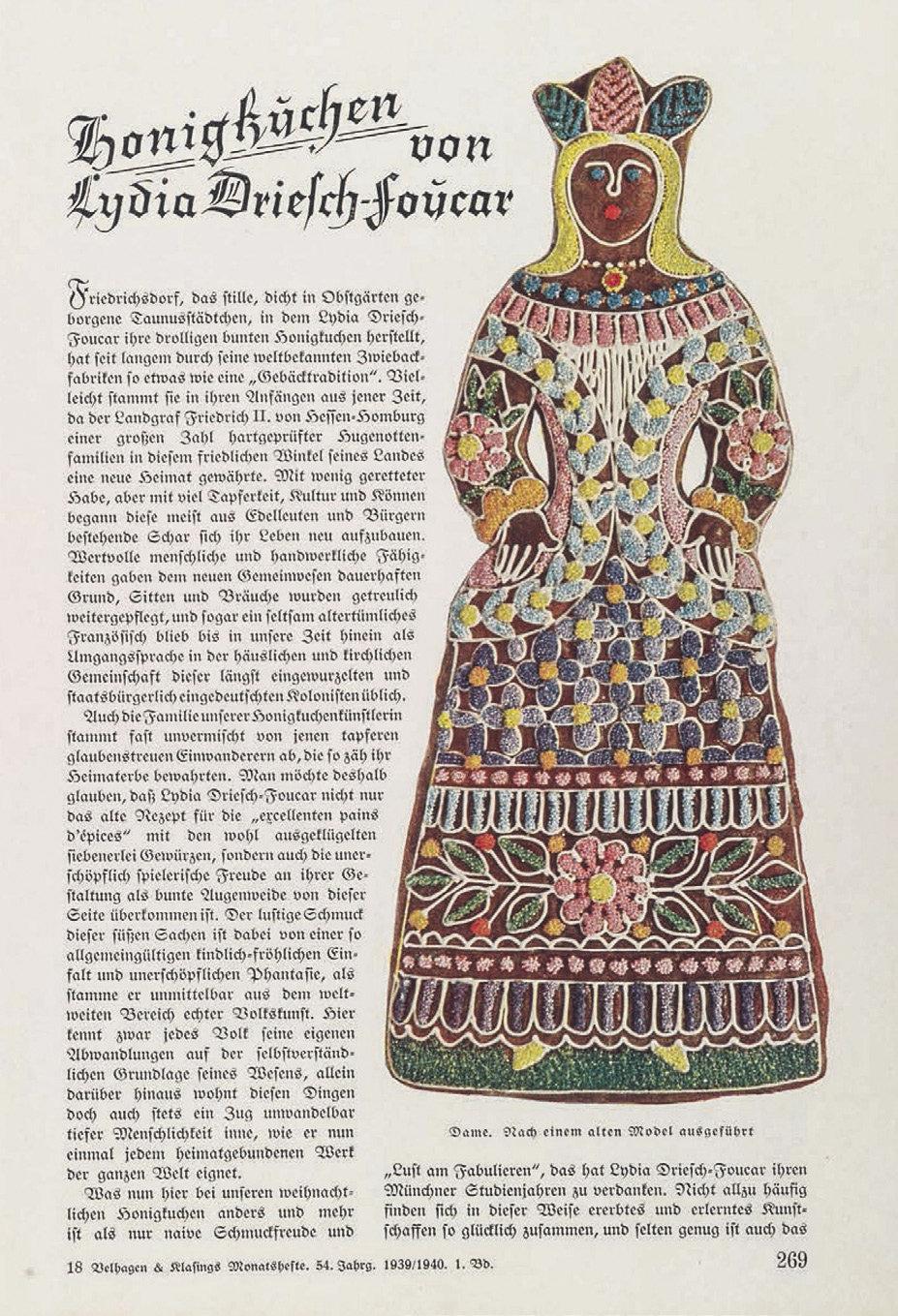

Lydia Driesch-Foucar, Honigkuchen (honey cake) design, 1939–1940

In this circle of friends, the cakes were originally a sign of connection and friendship; particularly during difficult economic times, edible gifts were especially appreciated. But this business venture was not initially profitable either, and Driesch-Foucar opened a small candy and tobacco shop. In March 1934, however, she successfully made the leap to exhibitor at the Leipzig Spring Trade Fair. A photograph from the Grassi Museum’s archives shows what was probably her first stand, which bears her name alone, “Lydia Driesch Friedrichsdorf.” Pictured is a simple sales counter in front of a wall tiled with gingerbread cookies.

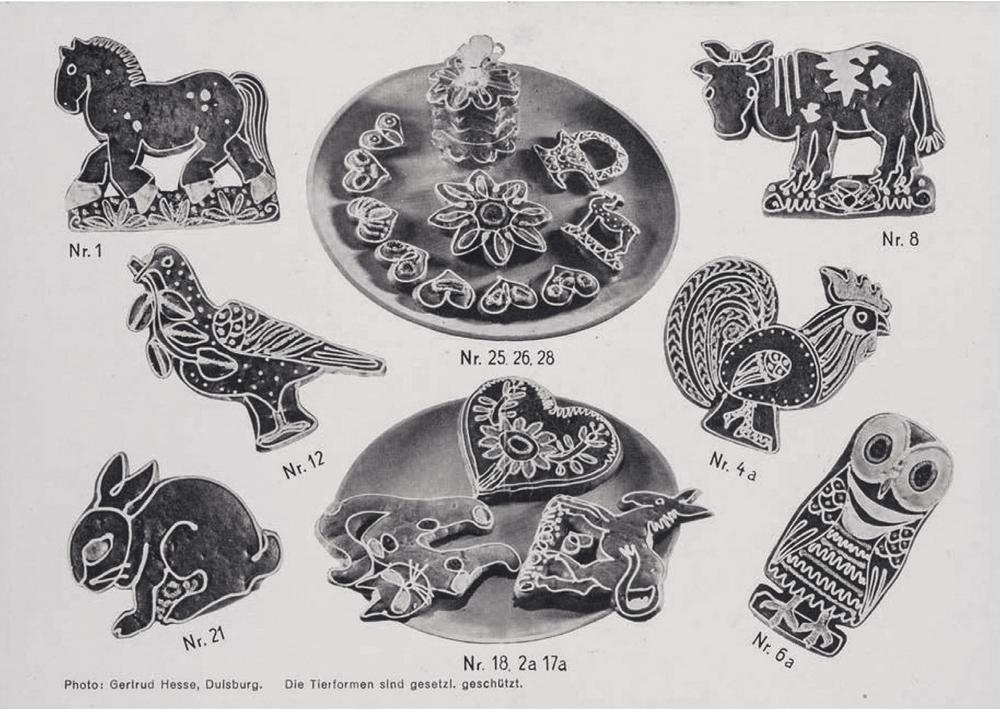

Promotional leaflet for the “Werkstatt für künstlerische Formhonigkuchen” (“Workshop for artistically-shaped honey cake”), c. 1935

Meanwhile she had been accepted into the Reich Chamber of Culture (Reichskulturkammer) as a member of the Association of German Craftsmen (Bund Deutscher Kunsthandwerker). Permission to participate in the Museum of Applied Arts’ trade fair hinged on a positive evaluation of the exact products to be exhibited from the museum’s direction; the Grassi Museum introduced this selection principle in 1920 and consequently became the premier exhibitor of quality handicrafts. Driesch-Foucar received authorization to sell her products at the trade fair, which implicitly legitimized her gingerbread cookies as a handicraft, a fact also reflected in her stand’s unusual name—“Werkstatt für künstlerische Formhonigkuchen” (“Workshop for artistically-shaped honey cake”). On the exhibitor list of the 1936 Leipzig Spring Trade Fair, a separate category, “Honigkuchen,” was even created for her. Driesch-Foucar gained a foothold with a food item at an exhibition otherwise dedicated to household products, textiles, and furniture, all the while upholding principles of good design and exemplary craftsmanship.

Surviving photographs show modern designs rather than traditional German Lebkuchen shapes; they are artistically transformed and brought to life by decorative colored icing and sugar pearls. Despite their beauty, these unsigned gingerbread cookies were conceived as edible artistic objects—a kind of precursor to the Eat Art movement. As Driesch-Foucar later recalled: “The success was greater than anticipated. I received so many orders that I could hardly keep up with them. A workshop was set up in the side wing of the house, and a few female assistants were trained. Wealthy friends helped me purchase a larger oven.” With a touch of irony, she later recalled Adolf Hitler’s visit to her stand: “I handed Hitler a later model of the Christmas cookie horse [at the Leipzig Trade Fair]. He was very pleased with my stand.”

The trained porcelain artist’s successes went hand in hand with her workshop’s increasing professionalization in production, distribution, advertising, and sales. Driesch-Foucar had business flyers, brochures, and price lists that were also order forms printed. Logically, she also patented her designs to stave off counterfeits; starting in 1936, she used her new logo and marked it “registered” (Gesetzlich geschützt). The brochures show her repertoire of shapes, which included all the signs of the zodiac, and an attractive cookie box. They note explicitly that “cookie samples will not be sent, because they return damaged.” The models were photographed by Jutta Selle (Berlin) and Gertrud Hesse (Duisburg), the two most notable product photographers of the late 1920s and 1930s. Photographs of her cookies appeared, for example, in the 1936 Christmas edition of the renowned women’s magazine Deutsche Frauenkultur, in which Driesch-Foucar was explicitly referred to as an artist. Two years later, her supporter Marcks informed her: “At Christmastime, the entire city of Berlin was decorated with your Kuchen—several shop windows at Wertheim’s alone. Did it pay off for you too? What a wide selection!” The success motivated her to license her cookies to Kay Dessau’s department store in Copenhagen in 1937. But with the outbreak of the war, production ceased both in her home workshop as well as at the Danish franchise.

Cookies, even if they are not eaten, are perishable, which, when one considers the classical art-market repertoire, raises the question of preservability. Nevertheless, as early as 1934, the local history museum in Erfurt (Heimatmuseum) was interested in putting examples of the cutout cookies “behind glass.” The following year, the Berlin Museum of German Folk Art in Bellevue Palace also expressed an interest and, in July 1936, she was invited by Walter Passarge, director of the Kunsthalle Mannheim Museum, to participate in a “special exhibition of contemporary German decorative arts.” Passarge wrote afterward: “Your lovely Kuchen were, of course, once again very well liked; they were among the ‘big hits’ of the exhibition. The chief mayor was delighted. A portion has been sold; the rest, we will keep for the permanent contemporary arts and crafts exhibit I am currently assembling.” In Deutsche Werkkunst der Gegenwart (Contemporary German Decorative Arts), he created a separate section for her cookies, “Gebäck,” (biscuits) and both the 1937 and the expanded 1943 editions of the successful book contain two photographs of her work. The volume also included a statement by Driesch-Foucar presenting herself as an artistic designer.

Ultimately, it was her admission to the trade fair that had made Driesch-Foucar’s success on the museum scene at all possible. Later, the folk-art trend in Nazi design promoted her success. But the fact that her work fitted so well within Nazi culture would later prove detrimental to her reception (and profits) as a designing artist. Looking back, she later stated: “It was the only undertaking in which I succeeded, just not in a financial way unfortunately”; and “for all the time and effort spent, too little remained of the earnings.” The war years also took their toll: in 1942, the Grassi Museum did not hold its trade fair, and, in February 1943, she announced the closing of her workshop. “The honey from my bees, the garden, and the little shop, together with a goat, helped us get through the war years.” After 1945, Driesch-Foucar again took up baking as a Christmas hobby; in 1965, she sent her gingerbread cookies all the way to Walter and Ise Gropius in the United States of America, explaining that they had been made “in the best Bauhaus tradition.” As a final project, she immortalized examples of the artistic cookies, which are preserved today in the Bauhaus Archives in Berlin. Driesch-Foucar’s cookies shifted from a symbol of friendship to a profitoriented form of Frauenschaffen (“woman’s work”), to works of folk or decorative art, and ultimately to symbols of the Bauhaus.

Two gingerbread designs by Lydia Driesch-Foucar, c. 1939–1940

“It was the only undertaking in which I succeeded, just not in a financial way unfortunately. For all the time and effort spent, too little remained of the earnings.”

Lydia Driesch-Foucar