Born: Margarete Heymann, August 10, 1899, Cologne, Germany

Died: November 11, 1990, London, UK

Matriculated: 1920

Locations: Germany, UK

In photographs, the Bauhaus tends to appear black and white and rather rectilinear. The explosive color and playful designs of Bauhaus ceramicist Margarete Heymann-Loebenstein definitively refute this impression. She embodied interwar and Bauhaus “new womanhood” like few others. Sure, she had the look, as a portrait of her with cropped hair and a man’s shirt and tie shows. But her emancipation went much deeper. At the Bauhaus, she challenged those who tried to keep women out of the ceramics workshop. At twenty-four, she co-founded a highly successful business, Haël Werkstatten für Künstlerische Keramik (Haël Workshops for Art Pottery), that accomplished the Bauhaus ambition of bringing modernity home. And she even kept the business going through personal tragedy and the Great Depression. Only the National Socialist regime and its collaborators would prove to be too much for her.

Margarete Heymann grew up in a Jewish family in artistically vibrant Cologne. She studied painting at Cologne’s College of Applied Arts (Kunstgewerbeschule) and Düsseldorf’s Academy of Fine Arts (Kunstakademie), and Chinese and Japanese art history at the Museum for East Asian Art. In the fall of 1920, just twenty-one, she secured a place at the Bauhaus. She completed her first semester but was denied admission to her chosen workshop, ceramics; its leaders had simply decided not to accept any more women. She was offered a place in the bookbinding workshop, but Heymann was not to be deterred. The compromise was a provisional acceptance to ceramics, and in the spring of 1921 she began studying in Dornburg while continuing her classes at the Weimar Bauhaus with Paul Klee, Gertrud Grunow, and Georg Muche. During the following semester, her third, the Bauhaus masters again denied her full acceptance to the workshop. Its head, Gerhard Marcks, stated that both he and the master of form, Max Krehan, saw her as “probably gifted,” but not suitable for ceramics. Heymann protested, but the male leaders would not budge, so she left the Bauhaus for good.

In 1922 Heymann accepted a position as artistic assistant at the modernist Velten-Vordamm Ceramics in Velten, northwest of Berlin. The following year, she married the economist Gustav Loebenstein and, together with his brother Daniel, they founded a ceramics business to make modern, useful, and beautiful household items for individual consumers—an idea right out of the Bauhaus playbook. They acquired an abandoned ceramics factory in Marwitz, a village neighboring Velten, and named it “Haël,” the German pronunciation of the first letters of their last names. Heymann-Loebenstein was in charge of designing the firm’s tea sets, vases, cactus pots, smoking services, and other items; the brothers handled the business.

Haël symbol

Aside from great design, from the start Haël had something its competitors lacked: smart branding. Every Haël piece is identifiable by the company’s symbol, a visual puzzle of a circle and lines that resolves into the letters H and L—perhaps with an “a,” “e,” and an umlaut evoked too. Sales of Haël products took off, thanks to its three young leaders who made sure that their delightfully modern ceramics were seen at fairs and in advertisements. Like the public, the critics immediately took to Haël. A 1924 article in Kunst und Kunstgewerbe (Art and Applied Arts) by Fritz Wendland enthuses about this new attempt “to develop a rather fresh and generous adornment on simple, pleasing forms, with such a clear emphasis on the hand-painted stroke that one unwittingly thinks of the sturdy household items of times past … The folk craftsmanship to which these works aspire draws from a thoroughly modern conceptualization of forms, colors, and ornamentation.” Heymann-Loebenstein, like most Bauhaus members of this time, moved increasingly to a constructivist approach that focused on simplicity of form. A tea set based on circles and triangles, referred to today as the “Scheibenhenkel” (disk-handled) set from the later 1920s, epitomizes this simplicity in its playful manner. Available in an array of bright colors, the Scheibenhenkel tea and coffee sets became a signature Haël form, and not only in ceramics; Heymann-Loebenstein also created a version for Haël’s smaller line of luxury metal products.

“Scheibenhenkel” (diskhandle) Haël Tea Set, c. later 1920s, glazed stoneware, design 181, glaze 26

“The folk craftsmanship to which these works aspire draws from a thoroughly modern conceptualization of forms, colors, and ornamentation.”

Fritz Wendland

By the late 1920s, Haël had approximately one hundred employees, and its products were being exported to France and England and as far away as Africa, Australia, South America, and the United States of America. But in 1928, tragedy struck when her husband and brother-in-law died in a car accident while driving to the famed Leipzig Fair to represent Haël. Heymann-Loebenstein was left alone to lead the firm as head of design and to run the business—as well as to raise her two children. She accomplished this, and even kept the business going through the global Great Depression that began in 1929. A review from that year in Die Schaulade (the Showcase) singles out her talents; “The (female) director of the Haël-Workshops is involved in the artistic and business development of this factory to a considerable extent and constantly strives to produce new and even further improved goods.” In 1932, with the ongoing financial crisis, Heymann-Loebenstein innovated the Norma series. A brochure describes it: “The fine, unglazed finish in standardized form, we present ‘Haël-Norma,’ the first ceramic series-service. Manageable by design, beautiful in appearance, durable in use—and one thing more: an astonishingly low price distinguishes the ceramic series HAËL NORMA.” Standardization meant lower production costs, and Norma was available in only a few colors, a signature sunny yellow, black, or brown, always with a white interior.

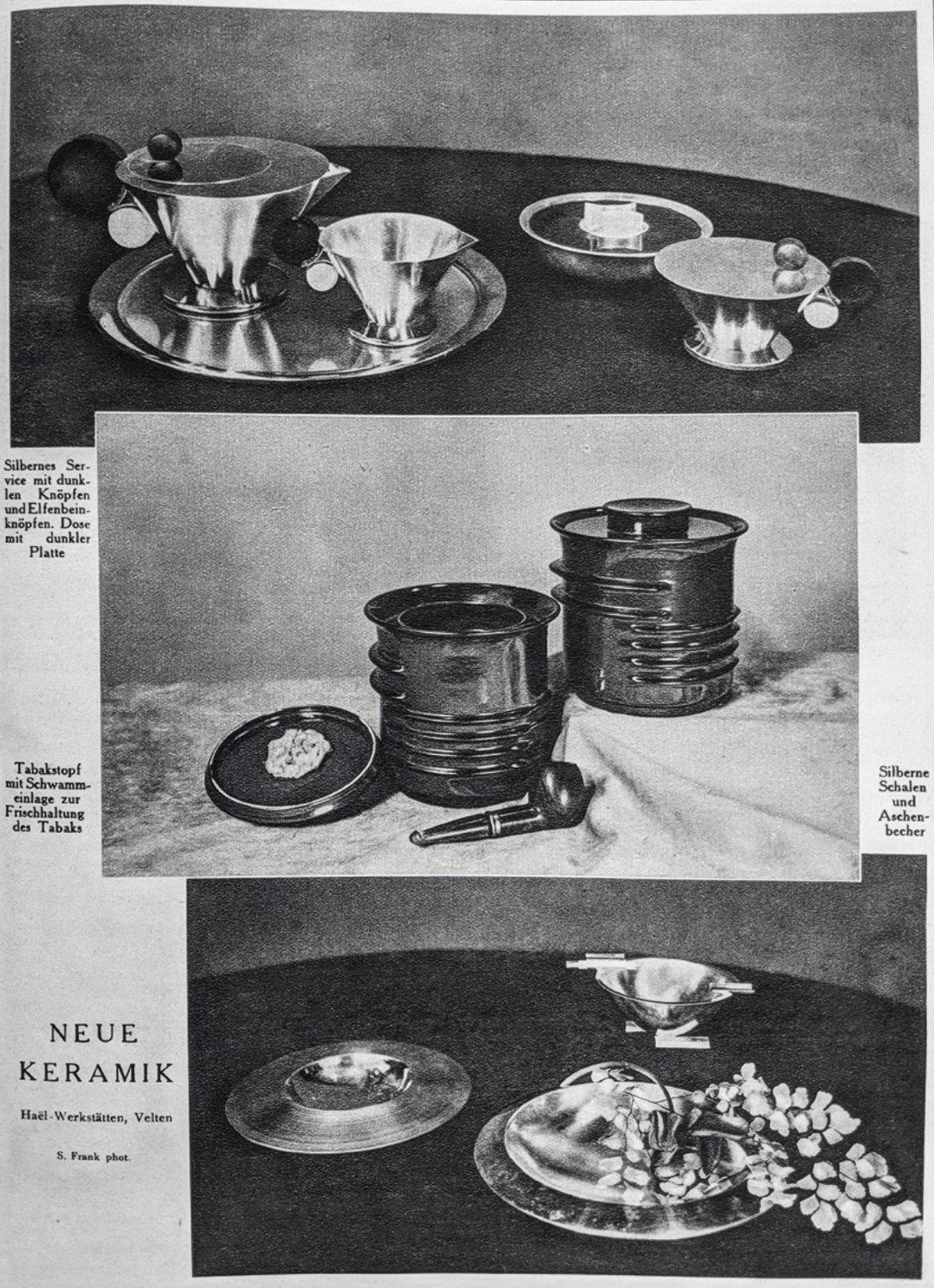

“New Ceramics: Haël Werkstätten, Velten,” in the journal Haus Hof Garten, 1929. From top: silver tea service with ivory and dark “button” handles; tobacco pot with sponge holder to keep tobacco fresh; silver bowls and ashtray

Shortly after the Nazis assumed power at the start of 1933, all seemed well at Haël. The firm announced that it would again show at the Leipzig Fair; March brought a positive review of their latest products in Die Weite Welt (The Wide World). But the political climate was changing quickly, and in July Heymann-Loebenstein was reported to the National Socialist authorities “for contempt and dismissal of the German state authority” by two disgruntled employees. Knowing the danger she was in, she decided to close the factory. At the end of April 1934, Heymann-Loebenstein sold Haël’s buildings, ovens, ceramic molds, and complete list of clients for 45,000 Reichsmarks to Dr. Heinrich Schild, who placed it in the hands of a young ceramicist named Hedwig Bollhagen. The price was so low that Heymann-Loebenstein was twice compensated in subsequent decades by the German government.

Haël “Norma” Tea Set, earthenware with colored glaze, 1932 or 1933

A 1935 article, “Jewish Ceramics in the Chamber of Horrors,” in the Nazi propaganda rag Der Angriff, told a very different tale. It celebrated the return of “German” ceramics to Marwitz after the “Jews” had abandoned their factory and left their employees destitute:

Fourteen months long rats and bats sought amusement here every night. Until the great purification began. Since April 1934, the company has a new master. Young workers created a new factory in a few months. Nearly forty men and women from Marwitz and the surrounding area stand under the symbols of the German Labor Front [i.e. a Swastika inside a gear]; since September 1st, 1934 [they are] at their workbenches again, kneading and turning [potters wheels], painting and firing according to the old customs of craftsmanship. A young woman stands among them as head of the factory.

The article lies outright about many details, but most unjust of all is the fact that, according to cultural historian Ursula Hudson-Wiedenmann, over fifty percent of Bollhagen’s “German” designs—including most of those shown in a photograph accompanying the article as the “beautiful German” designs—were not hers, but simply those of Heymann-Loebenstein. Bollhagen used the same forms but changed the glazes and stamped her initials on them, a trick she picked up from Haël.

Four ceramic objects by Margarete Heymann-Loebenstein (later Grete Marks), produced by Haël-Werkstätten, Marwitz, 1923–1934

Heymann-Loebenstein stayed in Berlin for two more years before immigrating to the United Kingdom in December 1936. She quickly found work designing for British firms through her business contacts and even attempted to reproduce some of her Haël designs, including a toned-down version of the Scheibenhenkel coffee service. She married a British man, Harold Marks, in 1938, and was henceforth called Grete Marks. She founded her own Greta Pottery, with a few employees, but with the war’s outbreak, she closed the business. Her daughter Frances Marks was born in 1941, and, after the war Grete Marks painted and created free-form studio pottery. Haël remained the apex of her impact on the broad public, for whom she created a unique brand and gave them the chance to bring modernity home.