Born: Benita Koch, May 23, 1892, Stuttgart, Germany

Died: April 26, 1976, Bielefeld, Germany

Matriculated: 1920

Locations: Germany, Czechoslovakia (now Czech Republic)

The weaver Benita Otte was among those students who applied to the Bauhaus having already amassed a wealth of professional experience. Before the First World War, she had graduated from the Secondary School for Girls (Lyzeum) in Krefeld in 1908 and, five years later, passed the first of a series of teaching examinations: the teaching exam at the Düsseldorf Drawing Academy; then, a national teachers’ examination (staatliche Prüfung) for gymnastics instruction at the Women’s Educational Association (Frauenbildungsverein) in Frankfurt in 1914; and the following year, another national examination to become a certified needlework teacher in Berlin. She was highly qualified when she began teaching at the Municipal Secondary School for Girls (Städtische Höhere Mädchenschule) in Uerdingen, where from 1915 to 1920 she taught needlework, gymnastics, and drawing. She became a fully certified teacher in 1918. This also meant that she was already twenty-eight years old when she decided to continue her own education at the Bauhaus in Weimar. The catalyst for this decision was likely a 1919 exhibition of her work at the former Weimar Museum of Fine and Applied Art, through which she would have had an opportunity to learn about the Bauhaus. In contrast to many of her school friends, she was well prepared in terms of her expertise and teaching experience.

After Koch was admitted to the school for the summer semester of 1920, the first classes she took were in the weaving workshop. Just a few years later, she enrolled in two additional advanced-training courses in her hometown: a dyeing class in 1922 at the textile school in Krefeld, and two years later, a so-called Fabrikantenkursus (“manufacturer’s class”) in weaving and material theory at the silk-weaving school in Krefeld. These qualifications along with her 1923 journeyman project (Gesellenarbeit) not only qualified her to teach at the Bauhaus herself but also made her an important contributor in the preparation of the Bauhaus exhibition in 1923. For the model Haus am Horn, she conceived the washable rug in the children’s bedroom and, more notably, a “functional kitchen,” a design that anticipates the logic as well as several elements of Schütte-Lihotzky’s “Frankfurt Kitchen.” Walter Gropius even did her the honor of entrusting her with the design of a rug for his Bauhaus director’s office.

Because of her success, Otte did not stay with the Bauhaus long during its relocation from Weimar to Dessau. Instead—enlisted by the former Bauhaus director Gerhard Marcks—she took an attractive position as a specialized teacher and artistic director of the hand-weaving workshop at the Burg Giebichenstein School of Art and Design in Halle (Saale) in the fall of 1925, commonly known as “die Burg.” Among the many former Bauhaus members who “stürmte die Burg” (“stormed the castle”) was her former schoolmate Heinrich Koch, who played saxophone in the Bauhaus band at a “Burg” party. The two were married in 1929, after which Koch enrolled at Burg as a photography student, eventually serving as chair of its photography department. Like all former Bauhäusler at Giebichenstein, in May 1933, the couple was fired and stripped of their teaching licenses by the Nazi regime, just months after its rise to power. Their relocation to Heinrich’s home city of Prague, in what was then Czechoslovakia, also meant—at least initially—the end of Benita’s career as a weaver. Heinrich found a position as a photographer at the National Museum, where he was tasked with creating a photographic archive, and compelled his wife to work with him on the project.

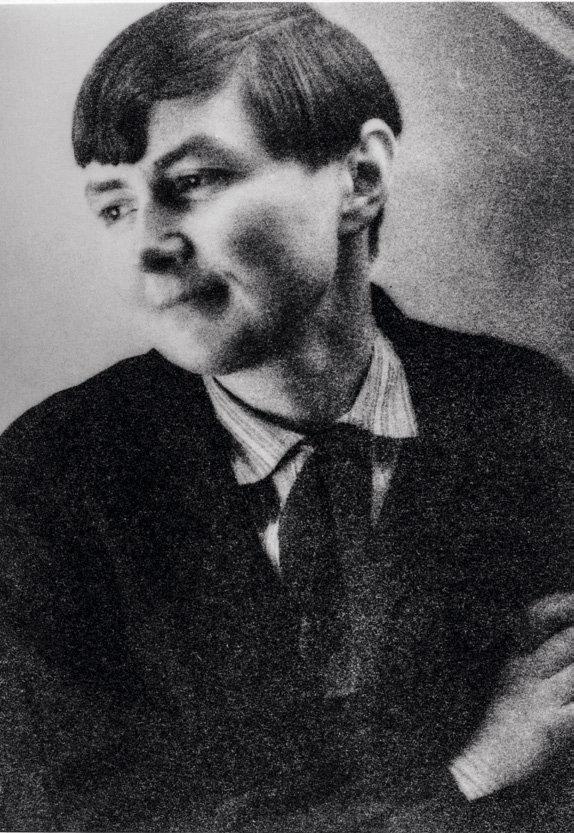

Benita Koch-Otte, Rug for a children’s room, 1923

When Heinrich was killed in an accident in 1934, Benita was forced to establish a livelihood again. She called on old contacts and took up directorship of the weaving workshop at the Bethel Institution (Von Bodelschwinghsche Anstalt Bethel), a facility in Bielefeld, Germany, for people with epilepsy, or with physical or mental disabilities. She took her master craftsman’s examination (Meisterprüfung), administered by the Bielefeld Chamber of Commerce, in 1937. Determined to serve those in need of care and the long-term unemployed at the facility, this often meant not only turning away from modernism for good but also facing an endless balancing act (and quite a few concessions) dealing with those in power. For a photographic series in 1937, the New Objectivity photographer Albert Renger-Patzsch documented the weaving workshop’s work, thereby also photographing the residents. With the adoption of the Nazi euthanasia program, these people, deemed “degenerates” by the fascist regime, became a political issue. Koch-Otte kept a Christian, charitable approach to life and devoted herself to Catholicism; at Bethel, she also continued her therapeutic work and trained apprentices and journeymen even after her retirement in 1957.