Ré Soupault

Ré Soupault, self portrait in front of photographer Georg von Hoyningen-Huene’s house, Tunisia, 1939

Born: Meta Erna Niemeyer, October 29, 1901, Bublitz, Pomerania, Germany (now Bobolice, Poland)

Died: March 12, 1996, Versailles, France

Matriculated: 1921

Locations: Germany, Italy, France, Norway, Spain, UK, USA, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Mexico, Guatemala, Panama, Colombia, Peru, Chile, Argentina, Brazil, Switzerland, Canada

It was not until the fascists in Tunisia arrested her husband Philippe and Ré Soupault feared him dead that she broke down. “That is why, I believe, I can’t cry anymore. In that moment, I cried out all of my tears.” A woman of many names—Erna Niemeyer, Ré Richter, and Renate Green—Ré Soupault traveled the world and became a central member of the avant-garde; she worked in film, clothing design, photography, and as a translator and writer. But it all started at the Bauhaus.

Erna Niemeyer, her name until Kurt Schwitters dubbed her “Ré” in 1924, came from a conservative household in Bublitz, Pomerania, now Bobolice, Poland. “Everything was gray in the hopelessness at the end of the war, nowhere a bright spot. Then Miss Wimmer, my drawing teacher—the only sensible person at my school—showed me Gropius’s manifesto. The Bauhaus. That was an idea, more, an ideal; no difference between draftsmen and artists. Everyone together in a new community, we should build the ‘cathedral’ of the future. I wanted to be a part of it.” Niemeyer was only twenty when she matriculated in spring, 1921 and began a year in Johannes Itten’s preliminary course. She recalled: “With Itten, something happened that freed us. We did not learn to paint, but learned to see anew, to think anew, and at the same time we learned to know ourselves.” She became interested in Itten’s hybrid, Zoroastrian-influenced religion, Mazdaznan, and studied Sanskrit. The Bauhaus’s revolutionary atmosphere impacted Niemeyer so profoundly, that her family sought to have her declared insane to bring her home. Gropius convinced them otherwise, and in April of 1922, she joined the weaving workshop. She wove Sanskrit phrases into a rug that was later shown and sold at the 1923 Staatliches Bauhaus exhibition.

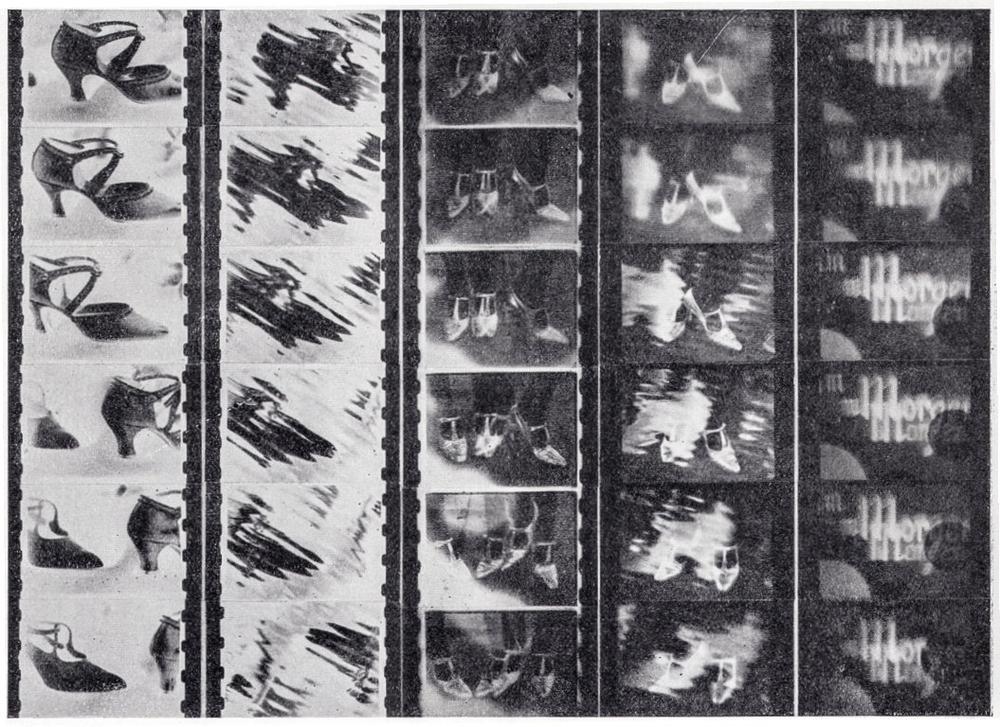

Through her friend Bauhäusler Werner Graeff, Niemeyer met the experimental filmmaker Viking Eggeling in Berlin in 1923 and became romantically involved with him. She took leave from her Bauhaus studies and worked as Eggeling’s assistant for a year, learning the ropes of filmmaking; in return she completed the Symphony Diagonal, now celebrated as one of the most significant abstract films, something Niemeyer called “optical music.” Completely exhausted, sick, and undernourished, she returned to Weimar and soon learned that Eggeling had fallen severely ill. She traveled to Italy to recover. After Eggeling’s death in 1925, Niemeyer made her own films including a Modefilm (“Fashion Film”) from which she extracted frames showing dancing shoes and feet to compose a new kind of picture. This picture was published in art historian Hans Hildebrandt’s 1928 book on women artists, which listed her as Renate Green, the name Niemeyer chose for art and journalism.

Renate Green (Ré Soupault), film frames from “Teile aus einem Modefilm: Tanzschuhe beim Charleston” (Fashion film, dancing shoes doing the Charleston)

In 1926 she married Dadaist Hans Richter, whom she had first met at the Bauhaus in 1922; their Berlin apartment became a center for avant-garde socializing with friends including Sergei Eisenstein, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Fernand Léger. Ré Richter started work as a fashion journalist for the magazine Sport im Bild (Sport in Pictures) but by 1927 she and Richter had separated—their divorce only finalized in 1931—and she left to work as a foreign correspondent in Paris. She quickly integrated into avant-garde circles; among her friends were Fernand Léger, Man Ray, Lee Miller, Kiki of Montparnasse, and Florence Henri, who took ravishing, semi-nude photographs of her.

Given her Bauhaus skills and her work in fashion, it was only a matter of time before Ré became a designer herself. American millionaire Arthur Wheeler, whom she met at a birthday party for Kiki thought Ré looked “like a million dollars,” and financed her company, Ré Sport. The shop opened in 1931 with décor by Mies van der Rohe (by this time the Bauhaus’s director), but she had already created her most original invention in 1930: the transformation dress. This was a garment for busy, fashionable women that could be turned into ten completely different looks. “I always started with a concrete idea: a secretary or a saleswoman, etc., who wants to go out in the evening after work, but can’t go home beforehand, transforms her dress.” Reimagining clothing to match the unfolding life of New Women like herself, she created other transformation sets; culottes (Hosenrock) were for working women who played sports after work or wanted to hop on a train for a weekend trip without packing. This clothing design idea was published in the Werkbund’s design journal Die Form and her collections were photographed by Man Ray and sold in department stores. Fashion journalist Helen Grund wrote in the Frankfurter Zeitung’s supplement Für die Frau (For the Woman) that Renate Green’s clothes were “designed according to completely new social principles.”

Ré Soupault, Kinder in Madrid, (Children in Madrid), 1936

Wheeler was killed in an auto accident, and Ré Sport was forced to close in 1934; Ré supported herself through private fashion clients and journalism. By this time she had already crossed the path of surrealist poet and journalist Philippe Soupault (at the Russian Embassy in 1933) and “then on April 1, 1934, we both stood on the street. Neither had a home anymore. We left for a reportage trip that same day.”

They traveled throughout Europe in Ré’s old Renault, and she took up photography in order to illustrate his articles. The switch from a film camera to a Rolleiflex 6x6 and later a Leica was easy for her, and Man Ray gave her a few pointers. She photographed people in Spain in 1936 as the country tumbled into civil war. A snap of a charming little girl defiantly raising her fist, repeating the grown-ups’ gesture of worker solidarity, captures what Ré would come to call the “magic second,” a distinctive marker of her work.

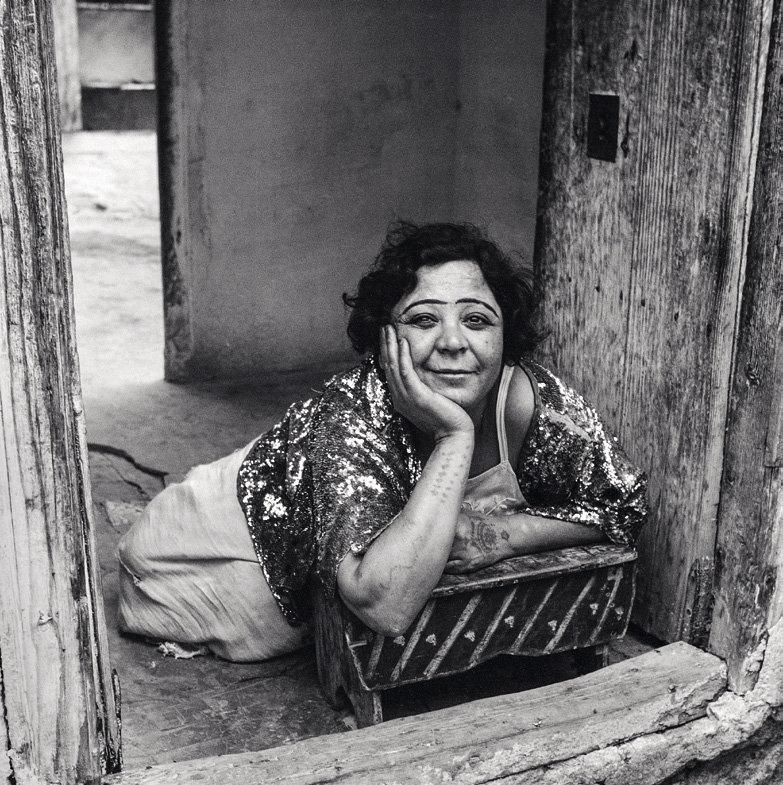

Ré Soupault, Untitled, Quartier Réservé, Tunis, 1939

The Soupaults married in 1937, and Ré Soupault took the name she used for the rest of her long life. In 1938 they relocated to Tunisia, still a French colony, for Philippe to found the anti-fascist Radio Tunis. In Tunisia she photographed expats, nomads, pilgrims, and the palace of the Tunisian monarch. The French government purchased her photographs for almost nothing. “It thus transpired that sometimes I saw my photographs in newspapers and magazines again under someone else’s name!” She received almost unheard of permission to photograph for two days in the company of a local policeman in Tunis’s “Quartier Réservé”—the confined quarters of women who were social outcasts or working prostitutes. Soupault catches them in their nearly empty rooms, where they return her empathetic gaze as individuals, by turns serious or warm.

In June 1940, the new Vichy regime fired all prominent anti-Fascists, including Philippe, leaving the Soupaults with no income. One day in March 1942 Philippe didn’t return home, and it was then that Ré believed him dead; she soon learned that he had been imprisoned on trumped-up charges of high treason. In November the same year, the pair left on the last bus to Algeria, only just escaping advancing Nazi forces. Leaving everything behind, all of Ré’s photographic negatives included; only much later would she learn from a Tunisian friend that a portion of her work—1,400 negatives—survived. The Soupaults were stranded in Algeria for a year before General Charles de Gaulle entrusted Philippe to build up a French news agency for all of the Americas. Arriving in New York in the summer of 1943 they were reunited with European expats including Bauhaus friends Herbert Bayer and Marcel Breuer. They traveled across Central and South America.

At the end of the war, and after numerous ordeals together, the Soupaults separated. Ré remained in New York in Max Ernst’s former apartment, working as a travel reporter. In 1946, she returned to Paris, and, unable to afford a camera, began a new career as a highly respected translator. After having moved more than forty times since 1943, she happily settled down in Basel, Switzerland in 1948. She bought a used camera and, in 1950, created a final reportage series, this one of German refugees from the eastern territories ceded to Poland. Together with Philippe, Ré made a film about Kandinsky in 1967, following which the pair both lived in the same building, each in an apartment within, from the early 1970s until Philippe’s death on March 12, 1990. She herself passed away six years later to the day, of heart failure, in Versailles, just outside of Paris.