Born: Annelise Elsa Frieda Fleischmann, June 12, 1899, Berlin-Charlottenburg, Germany

Died: May 9, 1994, Orange, Connecticut, USA

Matriculated: 1922

Locations: Germany, USA, Mexico

If there is one female Bauhaus artist who made an international name for herself, it is Anni Albers—a student at the Bauhaus in Weimar and Dessau from 1922 to 1931. When the Nazi Party came to power in 1933, she immigrated with her husband, Josef Albers, to the United States of America, where she worked as a freelance artist and designer, college instructor, author, and art collector. She consistently combined the traditional craft of weaving with synthetic materials, innovative techniques, and the intellectual process of abstraction in modern art, creating something new in the process. After her first trip to Mexico in 1936, ancient American art, specifically that of the Mayas and the Aztecs, became a lifelong source of inspiration, and in her later years, she devoted herself exclusively to abstract graphics.

Albers was born as Annelise Elsa Frieda Fleischmann to an upper-class family in Berlin in 1899, and baptized as a Protestant. Her mother belonged to the German-Jewish Ullstein publishing family, and her father was a furniture manufacturer. In 1922, Anni (remembered as a somewhat eccentric and difficult young woman) took her artistic ambitions to the Weimar Bauhaus. After a rocky start in the weaving workshop, she soon began passionately experimenting with “innovative textiles, striking due to their profusion of color and structure,” as she later described. Gradually she developed her own modern design vocabulary with abstract, symmetrical motifs and patterns reduced to basic forms for industrial production. Besides Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee, her most important teacher was her school friend Gunta Stölzl, who would become master of the weaving workshop in Dessau. In 1930, Albers earned her Bauhaus degree and temporarily ran the weaving workshop with Otti Berger after Stölzl left the school in 1931.

Ultimately, Albers’s forced emigration furthered her artistic development. Like her husband, she first taught at the newly founded Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Additionally, she designed fabrics for large companies such as Rosenthal and Knoll, and made rugs in her own hand-weaving studio. In the 1950s, her work took on a religious-philosophical dimension, something she also mentioned in her books. She came to believe that materials, patterns, and motifs offer an infinite variety of creations since they constantly present different possibilities in perception: a rigid surface pattern here, an opened space there, and elsewhere in the texture of a mandala. Albers returned to a practice that had driven her experimentation at the Bauhaus: not imposing her own will on objects, but to allow them to speak for themselves.

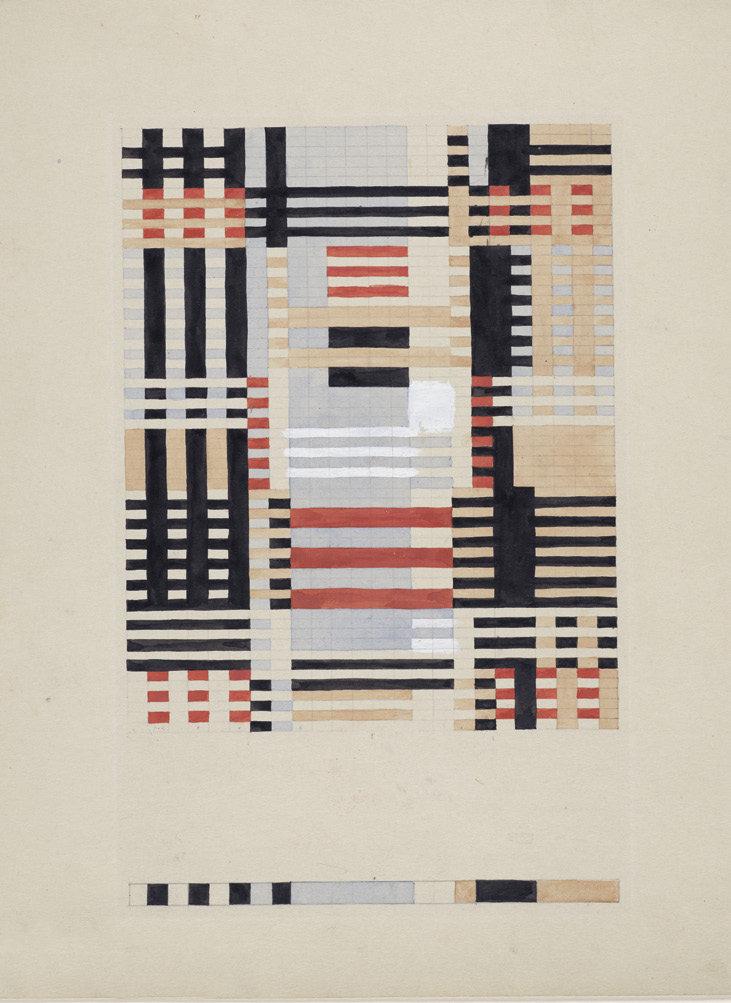

Anni Albers, design for wall hanging, 1926

She had married the Bauhaus junior master Josef Albers in 1925. He shared her obsession with innovative materials, such as glass, metal, and synthetics, and their professional life appears to have been extremely disciplined. Their personal life however—especially in the USA—was often tumultuous. It angered Albers that, publicly, she was so often seen primarily as the wife of her famous husband, rather than as an artist in her own right. This changed when, in 1949, she became the first weaver featured in a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In 1965, she received a commission from New York’s Jewish Museum to create a memorial to the victims of the Holocaust (Six Prayers). In 1975, her works were shown at the Kunstmuseum Düsseldorf (today the Museum Kunstpalast) and the Bauhaus Archive in Berlin for the first time, and in 1986, the most comprehensive monographic exhibition of her work was held at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. To date her work has been shown in 111 public exhibitions around the world; from Mexico to Tokyo, Venice to New York. At the age of ninety, four years before her death on May 9, 1994, she spoke of the essence of the Bauhaus’s early days in an interview: “What still interests me even today is that this searching in a realm of great freedom was fruitful—rather than somewhere, where a language is already spoken.”